Abstract

The participation of trypanothione in clinical and experimental antimony (Sb) resistance in Leishmania panamensis was examined by using specific inhibitors. Buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) significantly reversed the resistance to trivalent Sb (SbIII) of promastigotes of experimentally derived Sb-resistant lines, supporting the participation of a trypanothione-mediated mechanism of resistance. In contrast, promastigotes of strains isolated at the time of clinical treatment failure and resistant to pentavalent Sb (SbV) as intracellular amastigotes were not cross resistant to SbIII, and BSO had little or no effect on susceptibility. Difluoromethylornithine did not alter the SbIII susceptibilities of experimentally selected lines or clinical strains. The mechanisms of acquired resistance emerging in clinical settings may differ from those selected by in vitro exposure to Sb.

Antimonials (Sbs) have been the first line of treatment for all clinical forms of leishmaniasis for over 60 years (30). Treatment failure increasingly challenges the effective management of leishmaniasis (1, 19, 23, 29). Proof of the selection of resistant populations of Leishmania during treatment and the prospective demonstration of a causal link between treatment failure and drug-resistant Leishmania have recently been established with clinical isolates of the subgenus Viannia (26).

The mechanisms of action of Sbs remain uncertain; however, it is generally considered that pentavalent antimony (SbV) is a prodrug that is reduced to the active trivalent form (SbIII). This reductive activation evidently occurs inside both the parasite and the host macrophages (25, 27, 28). While downregulation of the genes encoding TDR1, AQP1, and ACR2 confers resistance to SbIII in vitro (12, 15, 30), the best-known mechanism of experimental resistance to Sb involves the detoxification of SbIII via the conjugation to trypanothione [T(SH)2] (13, 14, 18). The overproduction of T(SH)2 results from an enhanced capacity of the parasite to produce the precursors of T(SH)2, glutathione and spermidine, mediated by amplification of the gsh1 gene, which encodes γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS), and by the transcriptional overexpression of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), respectively (16, 17, 21). T(SH)2 synthesis can be interrupted with drugs that inhibit the synthesis of glutathione and spermidine. Inhibition of T(SH)2 synthesis could increase the efficacies of antimonial drugs in the presence or absence of drug resistance.

This study sought to determine whether T(SH)2 is involved in the experimental and acquired clinical Sb resistance of Leishmania panamensis.

The contribution of T(SH)2 to Sb resistance was determined with lines selected in vitro from the wild-type (WT) parental clone L. panamensis 1166 and paired clinical strains that were SbV sensitive when they were isolated at the time of diagnosis and presented secondary SbV resistance at the time of clinical treatment failure in patients treated with the standard regimen of meglumine antimonate (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Strains and lines of L. panamensis evaluated in this study

| Strain group, abbreviated code | Leishmania panamensis strain |

|---|---|

| 1166 WT | MHOM/COL/86/1166 |

| Selected in vitro as promastigotes with SbIII | |

| 800.3 | MHOM/COL/86/1166-800.3 |

| 800.5 | MHOM/COL/86/1166-800.5 |

| 1000.1 | MHOM/COL/86/1166-1000.1 |

| Selected in vitro as amastigotes with SbV, SRA898 | MHOM/COL/86/1166-SRA898 |

| Clinical strains (n = 26) | |

| Isolated from patients with successful treatment | |

| 3332 | MHOM/COL/99/3332 |

| 4790 | MHOM/COL/96/4790 |

| 6138 | MHOM/COL/02/6138 |

| Isolated from patients with clinical treatment failurea | |

| 3594 (I) | MHOM/COL/02/3594 |

| 3594 (R1) | MHOM/COL/02/3594-R1 |

| 3594 (R2) | MHOM/COL/02/3594-R2 |

| 3271 (I) | MHOM/COL/98/3271 |

| 3271 (R1) | MHOM/COL/02/3594-R1 |

| 3278 (I) | MHOM/COL/98/3278 |

| 3278 (R1) | MHOM/COL/98/3278-R1 |

I, isolated at time of diagnosis; R1, isolated at time of first relapse; R2, isolated at time of second relapse.

L. panamensis promastigotes were selected for SbIII resistance as described previously (7). The human promonocytic line U937 was cultured, differentiated to macrophages, and infected with promastigotes of the parental Sb-sensitive line 1166 WT (5). The in vitro selection of intracellular amastigotes for SbV resistance was achieved by culture of infected macrophages in RPMI medium containing an additive-free formulation of meglumine antimonate (Glucantime; lot BLO9186 90-278-1A1 W601; Walter Reed 214975AK). Amastigote-laden cells were exposed to increasing SbV concentrations, starting at the 50% effective dose (ED50) for the parental clone (7 μg SbV/ml) and increasing to 898 μg SbV/ml. Intracellular amastigotes were passaged twice in the presence of each SbV concentration.

The effects of inhibitors of T(SH)2 synthesis on parasites, monocytes, and macrophages were evaluated independently to determine the appropriate inhibitor concentration for reversion to Sb resistance. The number of viable cells was measured by using acid phosphatase, as described previously (4). Monocytes and macrophages that had been seeded at 1 × 105 cells/ml 2 days earlier were exposed to serial concentrations ranging from 0.063 to 10 mM of buthionine sulfoximine (BSO; Acros Organics, Morris Plains, NJ), difluoromethylornithine (DFMO; donated by Alan Fairlamb), and BSO-DFMO for 48 h. The effect of BSO and DFMO in combination with SbV on U937 monocytes/macrophages was measured by using 1 × 105 cells/ml exposed to 0.25 to 4 mM BSO and/or DFMO, followed 24 h later by the addition of 2 to 128 μg Sb/ml. The number of viable cells was evaluated 72 h later.

The dose-responses of log-phase (cultured for 48 h) SbIII-resistant and -sensitive promastigotes (Table 1) at 4 × 106/ml were determined with BSO (0.063 to 16 mM), DFMO (0.25 to 6 mM), and BSO-DFMO (each at 0.063 to 8 mM) for 48 h.

The effects of inhibitors of T(SH)2 synthesis on the ED50 of SbIII for promastigotes were evaluated with 2 × 106 parasites/ml exposed to 5 mM BSO, DFMO, and BSO-DFMO for 48 h and then resuspended at 4 × 106 parasites/ml and cultured with 16 to 1,024 μg SbIII/ml and 0.25 to 32 μg SbIII/ml for resistant and sensitive parasites, respectively. The viability index was defined as the optical density (OD) of parasites exposed to drugs divided by the OD of untreated parasites.

The ED50s of SbIII and SbV were calculated by using the probit model (6). Differences between treatments [T(SH)2inhibitors plus SbIII and SbIII alone] were calculated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test according to the data distribution. Mean ED50s were compared by use of the Duncan test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with data from at least three independent experiments, each comprising four replicates, with SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

BSO was nontoxic at concentrations of ≥5 mM for WT and SbIII-resistant promastigotes (viability index ≥ 95%), whereas 6 mM DFMO reduced the viability index of the SbIII-resistant lines by 14% and that of the susceptible strains by 30%. The toxicity of BSO-DFMO was similar to that of DFMO alone. Reversion assays were therefore conducted with 5 mM BSO and DFMO. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of propidium iodide-stained promastigotes confirmed the cytostatic activity of BSO and DFMO.

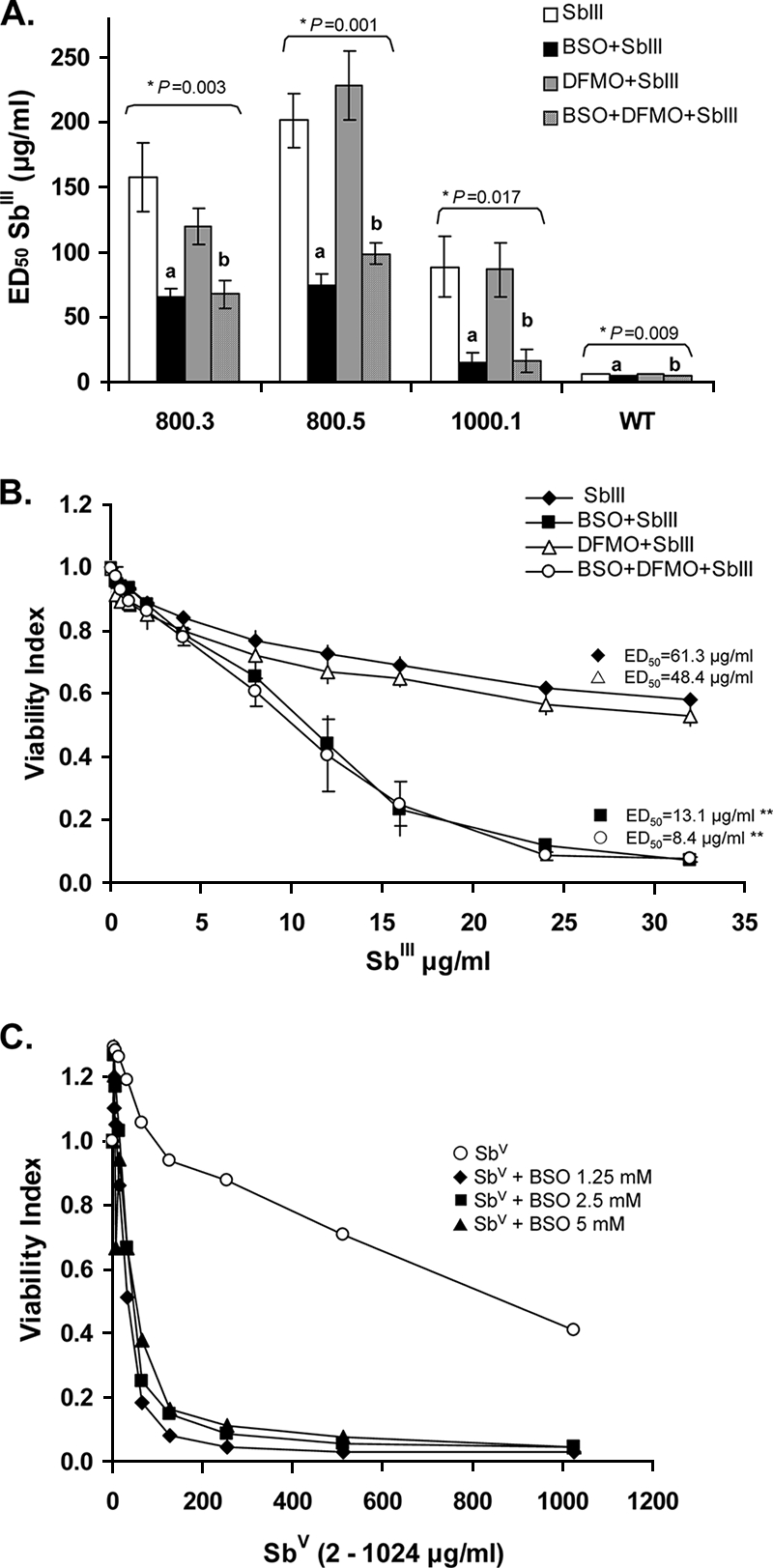

BSO treatment reduced the ED50s of SbIII for promastigotes of the resistant L. panamensis lines 800.3, 800.5, and 1000.1 by 58.32%, 62.92%, and 83.61%, respectively. The combination BSO-DFMO similarly reduced the ED50s of SbIII by 56.97%, 50.92%, and 81.13%, respectively (Fig. 1A). The reductions in the ED50s by BSO or BSO-DFMO were significant for each cell line: P < 0.003 for 800.3, P < 0.001 for 800.5, and P < 0.01 for 1000.1. DFMO did not significantly alter the ED50s of SbIII for these lines.

FIG. 1.

Effects of inhibitors of T(SH)2 synthesis on the susceptibility of the cloned parental 1166 WT, Sb-resistant lines generated by experimental selection in vitro, and U937 macrophages. (A) ED50s of SbIII for promastigotes of lines selected as promastigotes by using SbIII (error bars correspond to the mean ± 2 standard errors); (B) dose-response to SbIII of line SRA898, selected as amastigotes with SbV; (C) sensitivity of human U937 macrophages to SbV. alone and with different concentrations of BSO (the results of one representative experiment of three independent experiments performed are shown). The results of the statistical analyses are as follows: *, ANOVA, Duncan, P < 0.05 for SbIII versus BSO-SbIII (a) and SbIII versus BSO-DFMO-SbIII (b); **, Kruskal-Wallis, P = 0.026 for differences between SbIII versus BSO-SbIII and SbIII versus BSO-DFMO-SbIII.

Resistant line SRA898, selected as intracellular amastigotes by using SbV, presented a similar pattern of resistance (Table 2) and reversion as the lines selected as promastigotes with SbIII. The ED50s of SbIII for promastigotes were reduced by 78%, 21%, and 86% when they were treated with 5 mM BSO, DFMO, and BSO-DFMO, respectively (Fig. 1B) (P < 0.02 for BSO and BSO-DFMO treatment versus SbIII treatment alone).

TABLE 2.

ED50s of SbIII and SbV for clinical strains isolated before treatment and at relapse following treatment with meglumine antimonate and experimentally selected lines 1000.1 and SRA898

| Strain type and cell line | Strain characteristic | Mediana (minimum, maximum) ED50 (μg Sb/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promastigotes

|

Intracellular amastigotes, SbV (26) | |||

| SbIII | SbIII + BSO (5 mM) | |||

| In vitro-derived resistant strains | ||||

| 1000.1 | SbIII resistant | 109.7 (42.9, 113.8) | 17.4 (0.0, 26.3) | >128.0 |

| SRA898 | SbV resistant | 55.9 (53.9, 74.1) | 14.2 (9.6, 15.3) | >128.0 |

| Strains isolated from patients | ||||

| 3271 | Pretreatment | 4.3 (2.3, 5.8) | 4.8 (3.2, 6.9) | 14.9 |

| Relapse | 4.1 (2.5, 6.2) | 4.2 (2.4, 5.1) | >128.0 | |

| 3278 | Pretreatment | 3.4 (2.4, 4.5) | 3.5 (1.8, 5.5) | 14.4 |

| Relapse | 4.0 (1.6, 7.2) | 3.1 (1.1, 4.4) | >128.0 | |

| 3594 | Pretreatment | 2.8 (1.8, 5.7) | 2.5 (1.5, 3.7) | 7.6 |

| Relapse 1 | 4.2 (4.1, 5.5) | 3.8 (2.9, 3.9) | >128.0 | |

| Relapse 2 | 5.3 (3.9, 6.0) | 3.7 (3.3, 4.2) | >128.0 | |

Medians were calculated from three or four independent experiments.

Among the 10 clinical strains evaluated, only WT promastigotes demonstrated a significant reduction in the ED50 of SbIII (6.2 μg/ml ± 0.30 [standard error]) on exposure to BSO (4.9 μg/ml ± 0.20) and BSO-DFMO (4.7 μg/ml ± 0.15) (P < 0.009) (Fig. 1A; Table 2).

Strains that were isolated at the time of relapse and that were resistant to SbV as intracellular amastigotes were as susceptible to SbIII as promastigotes of the pretreatment SbV-sensitive strain (Table 2). There was no correlation between the ED50s of SbIII for promastigotes and the ED50s of SbV for intracellular amastigotes of clinical strains, whereas the ED50s of both SbIII and SbV were consistently high for resistant lines selected in vitro.

Monocytes proved more sensitive to inhibitors of T(SH)2 synthesis than macrophages. BSO reduced the viability index of monocytes by 27.3% at the highest dose tested (10 mM) but did not affect macrophages. DFMO at 10 mM reduced the viability index of monocytes by 42% and that of macrophages by 34.5%. The combination of BSO-DFMO reduced the viability index of monocytes by 88.2%; for macrophages, the viability index after exposure to BSO-DMFO was comparable to DMFO alone.

The reversion of resistance to Sb in intracellular amastigotes was not evaluable because of the high toxicity of SbV for the host cell when it was used in combination with inhibitors of T(SH)2 synthesis. Culture with 1.25 mM and 5 mM BSO or BSO-DFMO, followed by the addition of SbV, reduced the viability indices of macrophages by 76% and 82%, respectively (Fig. 1C). DFMO did not significantly increase the toxicity of SbV. The ED50 of SbV for macrophages was 858.9 μg Sb/ml.

Assessment of the drug susceptibilities of intracellular pathogens requires consideration of the potential interaction of drugs and toxicity for the host cell. Monocytes were significantly more sensitive to BSO than macrophages. This stage-specific effect likely reflects the lower replication rate of macrophages compared with that of monocytes; glutathione is produced in monocytes prior to mitosis, and BSO impairs replication (10). Nevertheless, BSO rendered U937 macrophages highly susceptible to SbV. Consequently, we were unable to evaluate the effect of BSO on the Sb susceptibilities of intracellular amastigotes. SbV alone was toxic for U937 macrophages in this study and a prior study (26), imposing an upper limit on the Sb concentration evaluable in susceptibility assays.

The partial reversion of SbIII resistance by BSO in experimentally selected parasites (Fig. 1A) supports the involvement of γ-GCS by increased transcription and translation or gene amplification. ODC evidently did not participate in the loss of susceptibility to Sb in these lines. Alternatively, the importation of exogenous polyamines (3) or synthesis via secondary pathways like the S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase pathway (3, 22) could have obscured the overproduction of ODC in Sb-resistant lines. The reduction of the ED50 of SbIII for the WT strain supports the potential role of γ-GCS in the Sb susceptibilities of clinical strains.

The loss of susceptibility to SbIII even after intense in vitro selection with SbIII or SbV was not completely attributable to T(SH)2-mediated detoxification, supporting the participation of other mechanisms. Clinical exposure and the acquisition of resistance to SbV did not lead to a loss of susceptibility to SbIII in the L. panamensis strains evaluated, and the inhibition of T(SH)2 synthesis had a limited effect on sensitivity to SbIII. In another clinical setting, γ-GCS, ODC, and AQP1 expression were reduced in Sb-resistant L. donovani strains in India and Nepal, yet Sb resistance was reverted by BSO (11, 20).

The dichotomy in the susceptibilities of clinical strains to different oxidation states of Sb contrasts with the cross-resistance of experimentally selected resistant lines to SbV as intracellular amastigotes and to SbIII as promastigotes. Since the selection of intracellular amastigotes with SbV in vitro led to the cross-resistance of the promastigote form to SbIII, the life stage per se does not explain the different outcomes of experimental selection with SbIII or SbV versus treatment with SbV. Both cross-resistance (20) and the absence of a correlation between susceptibility to SbIII and SbV (24) have been reported for clinical strains.

Transitory exposure to low concentrations of Sb during treatment with meglumine antimonate could select for mechanisms of resistance different from those achieved by in vitro selection. During standard treatment of leishmaniasis with meglumine antimonate, peak Sb levels in plasma are 20 to 40 μg/ml (8, 9). In vitro selection involves exposure to Sb concentrations 10 to 15 times higher over several weeks. The levels of antioxidants in Leishmania reportedly differ, depending on the life stage. L. donovani and L. major amastigotes have at least 10-fold lower concentrations of thiols, glutathione, T(SH)2, and ovothiol than promastigotes (2). This may explain the higher intrinsic susceptibility of amastigotes and the resistance of promastigotes to SbV. Furthermore, host cells can regulate entry and efflux and metabolize drugs targeted to intracellular pathogens. Hence, experimental in vitro selection may not mimic selection in vivo.

In summary, BSO significantly reverses the resistance to Sb in experimentally derived Sb-resistant lines of L. panamensis. This finding supports the participation of a T(SH)2-mediated mechanism of resistance in these lines. In contrast, strains isolated at the time of clinical treatment failure and resistant to SbV as intracellular amastigotes were not cross resistant to the presumptive active form of Sb (SbIII), and BSO had little or no effect on susceptibility. Our results provide evidence that mechanisms of acquired resistance emerging in clinical settings may be different from those selected by in vitro exposure to Sb, underscoring the need to clarify the mechanisms involved in clinical resistance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust-Burroughs Wellcome Fund Initiative in Infectious Diseases Program (contract 059056/Z/99Z). D.A.G.-P. was supported by a young investigator award from COLCIENCIAS/CIDEIM.

We thank Marc Ouellette for the SbIII-resistant lines of L. panamensis promastigotes and Ricardo Rojas for the SbV-resistant intracellular amastigotes. We are grateful to Alan Fairlamb for the gift of DFMO and acknowledge Mauricio Perez for conducting statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdo, M. G., W. M. Elamin, E. A. Khalil, and M. M. Mukhtar. 2003. Antimony-resistant Leishmania donovani in eastern Sudan: incidence and in vitro correlation. East Mediterr. Health J. 9:837-843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariyanayagam, M. R., and A. H. Fairlamb. 2001. Ovothiol and trypanothione as antioxidants in trypanosomatids. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 115:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basselin, M., G. H. Coombs, and M. P. Barrett. 2000. Putrescine and spermidine transport in Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 109:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodley, A. L., M. W. McGarry, and T. A. Shapiro. 1995. Drug cytotoxicity assay for African trypanosomes and Leishmania species. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1157-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosque, F., G. Milon, L. Valderrama, and N. G. Saravia. 1998. Permissiveness of human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages to infection by promastigotes of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis. J. Parasitol. 84:1250-1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bras, A. P., J. Janne, C. W. Porter, and D. S. Sitar. 2001. Spermidine/spermine N(1)-acetyltransferase catalyzes amantadine acetylation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 29:676-680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brochu, C., J. Wang, G. Roy, N. Messier, X. Y. Wang, N. G. Saravia, and M. Ouellette. 2003. Antimony uptake systems in the protozoan parasite Leishmania and accumulation differences in antimony-resistant parasites. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3073-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chulay, J. D., L. Fleckenstein, and D. H. Smith. 1988. Pharmacokinetics of antimony during treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with sodium stibogluconate or meglumine antimoniate. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82:69-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz, A., P. M. Rainey, B. L. Herwaldt, G. Stagni, R. Palacios, R. Trujillo, and N. G. Saravia. 2007. Pharmacokinetics of antimony in children treated for leishmaniasis with meglumine antimoniate. J. Infect. Dis. 195:602-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danfour, M., C. J. Schorah, and S. W. Evans. 1999. Changes in sensitivity of a human myeloid cell line (U937) to metal toxicity after glutathione depletion. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 21:277-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decuypere, S., S. Rijal, V. Yardley, S. De Doncker, T. Laurent, B. Khanal, F. Chappuis, and J. C. Dujardin. 2005. Gene expression analysis of the mechanism of natural SbV resistance in Leishmania donovani isolates from Nepal. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4616-4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denton, H., J. C. McGregor, and G. H. Coombs. 2004. Reduction of anti-leishmanial pentavalent antimonial drugs by a parasite-specific thiol-dependent reductase, TDR1. Biochem. J. 381:405-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Fadili, K., N. Messier, P. Leprohon, G. Roy, C. Guimond, N. Trudel, N. G. Saravia, B. Papadopoulou, D. Legare, and M. Ouellette. 2005. Role of the ABC transporter MRPA (PGPA) in antimony resistance in Leishmania infantum axenic and intracellular amastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1988-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairlamb, A. H., and A. Cerami. 1992. Metabolism and functions of trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:695-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gourbal, B., N. Sonuc, H. Bhattacharjee, D. Legare, S. Sundar, M. Ouellette, B. P. Rosen, and R. Mukhopadhyay. 2004. Drug uptake and modulation of drug resistance in Leishmania by an aquaglyceroporin. J. Biol. Chem. 279:31010-31017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grondin, K., A. Haimeur, R. Mukhopadhyay, B. P. Rosen, and M. Ouellette. 1997. Co-amplification of the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase gene gsh1 and of the ABC transporter gene pgpA in arsenite-resistant Leishmania tarentolae. EMBO J. 16:3057-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haimeur, A., C. Guimond, S. Pilote, R. Mukhopadhyay, B. P. Rosen, R. Poulin, and M. Ouellette. 1999. Elevated levels of polyamines and trypanothione resulting from overexpression of the ornithine decarboxylase gene in arsenite-resistant Leishmania. Mol. Microbiol. 34:726-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legare, D., D. Richard, R. Mukhopadhyay, Y. D. Stierhof, B. P. Rosen, A. Haimeur, B. Papadopoulou, and M. Ouellette. 2001. The Leishmania ATP-binding cassette protein PGPA is an intracellular metal-thiol transporter ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:26301-26307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lira, R., S. Sundar, A. Makharia, R. Kenney, A. Gam, E. Saraiva, and D. Sacks. 1999. Evidence that the high incidence of treatment failures in Indian kala-azar is due to the emergence of antimony-resistant strains of Leishmania donovani. J. Infect. Dis. 180:564-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittal, M. K., S. Rai, Ashutosh, Ravinder, S. Gupta, S. Sundar, and N. Goyal. 2007. Characterization of natural antimony resistance in Leishmania donovani isolates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76:681-688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukhopadhyay, R., S. Dey, N. Xu, D. Gage, J. Lightbody, M. Ouellette, and B. P. Rosen. 1996. Trypanothione overproduction and resistance to antimonials and arsenicals in Leishmania. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10383-10387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller, S., G. H. Coombs, and R. D. Walter. 2001. Targeting polyamines of parasitic protozoa in chemotherapy. Trends Parasitol. 17:242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palacios, R., L. E. Osorio, L. F. Grajalew, and M. T. Ochoa. 2001. Treatment failure in children in a randomized clinical trial with 10 and 20 days of meglumine antimonate for cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania viannia species. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 64:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rijal, S., V. Yardley, F. Chappuis, S. Decuypere, B. Khanal, R. Singh, M. Boelaert, S. De Doncker, S. Croft, and J. C. Dujardin. 2007. Antimonial treatment of visceral leishmaniasis: are current in vitro susceptibility assays adequate for prognosis of in vivo therapy outcome? Microbes Infect. 9:529-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts, W. L., J. D. Berman, and P. M. Rainey. 1995. In vitro antileishmanial properties of tri- and pentavalent antimonial preparations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1234-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rojas, R., L. Valderrama, M. Valderrama, M. X. Varona, M. Ouellette, and N. G. Saravia. 2006. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1375-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sereno, D., M. Cavaleyra, K. Zemzoumi, S. Maquaire, A. Ouaissi, and J. L. Lemesre. 1998. Axenically grown amastigotes of Leishmania infantum used as an in vitro model to investigate the pentavalent antimony mode of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3097-3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaked-Mishan, P., N. Ulrich, M. Ephros, and D. Zilberstein. 2001. Novel intracellular SbV reducing activity correlates with antimony susceptibility in Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 276:3971-3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundar, S., K. Pai, R. Kumar, K. Pathak-Tripathi, A. A. Gam, M. Ray, and R. T. Kenney. 2001. Resistance to treatment in kala-azar: speciation of isolates from northeast India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:193-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou, Y., N. Messier, M. Ouellette, B. P. Rosen, and R. Mukhopadhyay. 2004. Leishmania major LmACR2 is a pentavalent antimony reductase that confers sensitivity to the drug pentostam. J. Biol. Chem. 279:37445-37451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]