Abstract

We show that RsAFP2, a plant defensin that interacts with fungal glucosylceramides, is active against Candida albicans, inhibits to a lesser extent other Candida species, and is nontoxic to mammalian cells. Moreover, glucosylceramide levels in Candida species correlate with RsAFP2 sensitivity. We found RsAFP2 prophylactically effective against murine candidiasis.

Disseminated candidiasis is associated with high mortality and drug resistance (8, 22). Since treatment of these infections is ineffective in a number of cases, the search for new anticandidal compounds, as well as specific cellular targets, is critical. A molecular target studied by our group is the glycosphingolipid glucosylceramide (GlcCer; cerebroside), which is present at the cell surface (membrane and cell wall) of most pathogenic fungi (4, 15, 21) and is structurally distinct from its mammalian counterpart (1, 4, 14, 15, 17). Apart from structural features, GlcCers are important regulators of differentiation and pathogenicity of human and plant mycopathogens (7, 12, 14, 17-19, 21). All together, these characteristics make fungal GlcCer an attractive target for the development of new antifungal drugs. In this regard, it was previously demonstrated that passively administered anti-GlcCer antibodies prolong survival of mice lethally infected with Cryptococcus neoformans (20). Moreover, fungal GlcCers have previously been shown to constitute the target for RsAFP2, an antifungal defensin from radish seeds (27). Interaction between RsAFP2 and fungal GlcCer initiates a signaling cascade that results in the production of reactive oxygen species and fungal death (1).

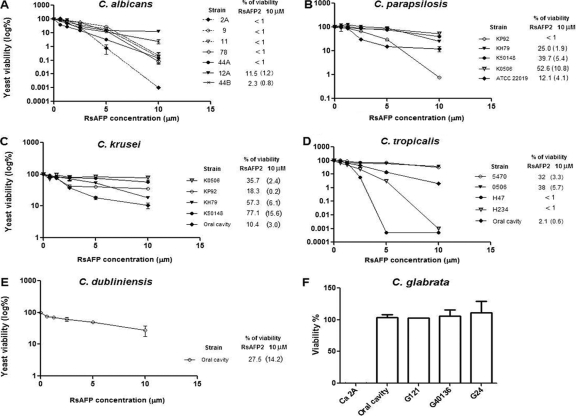

We evaluated the RsAFP2 activity as an anticandidal agent. RsAFP2 was purified as described previously (25) and tested against different Candida species and isolates. As demonstrated in Fig. 1, seven isolates of Candida albicans were susceptible to RsAFP2 in a dose-dependent manner. Different isolates of C. dubliniensis, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, and C. parapsilosis were also susceptible to RsAFP2 but to a lesser extent than C. albicans (Fig. 1B, C, D, and E). All tested C. glabrata strains were resistant to RsAFP2 (Fig. 1F), which is in accordance with the inability of this species to synthesize GlcCer (Fig. 2A) (23).

FIG. 1.

Susceptibility of different C. albicans strains and Candida species to RsAFP2. (A to E) Candida isolates and strains were cultivated in potato dextrose broth/yeast peptone dextrose broth (pH 7.0) for 24 h at room temperature (27). Yeast cells (2 × 103) were treated overnight with different concentrations (0.6 to 10 μM) of RsAFP2. The percentage of viability for each RsAFP2-treated Candida species relative to that of control treatment (water) was calculated after plating the treated yeast on brain heart infusion agar dishes for CFU counting. (F) C. glabrata and C. albicans (Ca 2A) isolates were treated with 10 μM RsAFP2. Survival rates, determined as the percentage of viability, of the different strains after treatment with 10 μM RsAFP2 are shown.

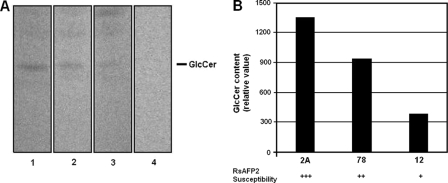

FIG. 2.

Correlation between GlcCer content and RsAFP2 susceptibility in Candida sp. (A) Expression of GlcCer by three different strains of C. albicans (lanes 1, strain 2A; 2, strain 78; 3, strain 12A) and one C. glabrata isolate (lane 4) (+++ indicates more susceptible; ++, intermediate susceptibility; +, less susceptible). GlcCer was extracted with organic solvents, and the resulting molecules were analyzed by high-performance thin-layer chromatography. (B) Densitometric analysis of the chromatogram shown in panel A for the different C. albicans strains was performed by using Scion Image (NHI) software, and the relative content of GlcCer in each strain is shown.

To establish a link between susceptibility to RsAFP2 and GlcCer content in C. albicans, we investigated the levels of cerebroside in the strains 2A, 78, and 12A, which were, respectively, highly, moderately, and weakly susceptible to RsAFP2 (Fig. 1A). Lipids from yeast cells were extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1, 1:1, and 1:2 [vol/vol]) (14). Extracts were pooled, dried, and partitioned according to Folch's method (9). Lipids from Folch's lower phase were normalized according to the total dry weight and analyzed with high-performance thin-layer chromatography plates developed with chloroform-methanol-water (65:25:4 [vol/vol/vol]). The spots were visualized by charring with orcinol-H2SO4 (24). To determine the relative amount of GlcCer, Scion Image software (NHI; Scion Corporation) was used. Orcinol-positive bands corresponding to standard fungal GlcCer were visualized in extracts of all C. albicans strains tested (Fig. 2A). Densitometry revealed a direct relationship between GlcCer content and RsAFP2 susceptibility (Fig. 2B). No bands corresponding to GlcCer were visualized in C. glabrata lipid extracts (Fig. 2A). In this regard, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which does not produce GlcCer, also is resistant to RsAFP2 (23, 27). Note that C. glabrata is phylogenetically closer to S. cerevisiae than to other species of the Candida genus (3, 11).

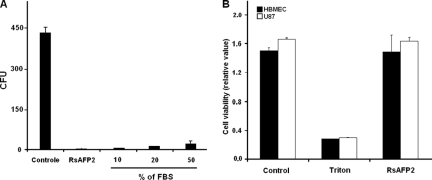

Inactivation of peptides by serum enzymes is a limiting problem for their systemic administration. To check the susceptibility of RsAFP2 to serum peptidases, Candida yeasts (2 × 103) were incubated overnight with RsAFP2 (10 μM), which was previously treated with 10, 20, or 50% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Gomesin (1 μM), an antimicrobial peptide susceptible to hydrolysis by serum peptidases, was used as control (2). After exposure to FBS, the remaining antifungal effect was evaluated. Treatment of RsAFP2 with serum did not result in significant changes of its antifungal effect (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, the presence of 10 and 20% FBS promoted a decrease of approximately 40 and 100% in gomesin activity, respectively (data not shown). Therefore, we concluded that, although serum enzymes were functional, they were not able to eliminate the RsAFP2 effect. We also evaluated the toxicity of RsAFP2 by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release (2, 6). Cell monolayers (human brain endothelial cells or strain U87) were incubated with RsAFP2 (10 μM) and culture supernatants collected after 24 h. Positive controls consisted of Triton X-100 (10%) lysates or culture supernatants of cells treated with 10 μM gomesin (2). RsAFP2 and untreated cells did not release significant levels of LDH (Fig. 4B). In contrast, gomesin and Triton treatments resulted in expressive enzyme release, indicating cell damage (not shown). These results support the conclusion that RsAFP2 has limited toxicity to mammalian cells.

FIG. 3.

Antifungal activity of RsAFP2 after treatment with serum and its toxicity to human cells. (A) After treatment with 10 μM RsAFP2 with different concentrations of serum (% of FBS), the peptide antifungal activity against C. albicans (strain 12A) cells (2 × 103) was assessed using CFU determination. (B) Monolayers of primary human brain endothelial cells (HBMEC) and the astroglia tumor-derived cell line (U87) in 96-well plates in serum-free medium were incubated overnight with RsAFP2 (10 μM), and culture supernatants were collected for LDH determination. Positive controls consisted of supernatants of Triton X-100 (10%) and gomesin (data not shown) cultures. The negative control corresponded to supernatant from untreated cells.

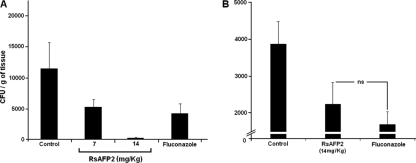

FIG. 4.

Activity of RsAFP2 in prophylactic murine models of candidiasis. Infection was performed at 1 h after (A) and 1 h before (B) RsAFP2 treatment. Mice (n = 5) were infected intravenously with C. albicans (strain 78) and treated with saline (control, n = 5), RsAFP2 (n = 5), or fluconazole (10 mg/kg) (n = 5). CFU counts in the kidneys of one representative experiment (out of three) are shown. Significant statistical differences (P < 0.01) were observed between antifungal-treated mice (RsAFP2 and fluconazole) and control mice (saline) in both experiments. Nonsignificant (ns; P = 0.152) differences were observed between CFU counts from RsAFP2-treated and fluconazole-treated mice in the prophylactic model. Procedures involving animals and their care were conducted in conformity with the local ethics committee and international recommendations.

Fungal burden in the kidney of infected mice was used to evaluate the prophylactic activity of RsAFP2 in murine models of infection with C. albicans, as described in previous studies (5, 16). Mice were inoculated intravenously via the lateral tail vein with 2 × 105 yeasts of C. albicans in saline. RsAFP2 was injected intravenously 1 h before or after the challenge with C. albicans (with 7 or 14 mg/kg of body weight, administered in 50 μl of saline). Four similar subsequent injections were made after 24-h intervals. Control groups were treated with 10-mg/kg doses of fluconazole or saline (10, 13) by following the same protocol. Mice were sacrificed 5 days after fungal infection. Kidneys were excised, weighed, and homogenized, and the pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (1 ml). Samples (100 μl) were plated onto solid brain heart infusion plates, and CFU were determined after 2 days. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, RsAFP2 considerably reduced the fungal burden in the kidney of infected mice on both administration models at least as efficiently as the standard drug, fluconazole, suggesting that under the conditions used in our study, the peptide controlled candidiasis caused by C. albicans.

Plant defensins are potent antimicrobial peptides (26). For instance, the in vitro antifungal activity of RsAFP2 was demonstrated by Thevissen and coworkers (1, 26, 27), using C. albicans, C. krusei, Aspergillus flavus, and Fusarium solani. In the present work, this finding was extended using different Candida species. Our results indicated that RsAFP2 is nontoxic to mammalian cells and remains active after serum treatment. The predominant C. albicans killing potential of RsAFP2, its nontoxicity for mammalian cells, and the fact that RsAFP2 can control candidiasis in vivo point to the potential of this defensin as a novel antifungal agent to combat C. albicans infections.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID), and Small Grants and FWO-Vlaanderen, Belgium (research project to B.P.A.C.). K.T. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from K. U. Leuven (industrial research fellow).

We thank Geralda R. Almeida for technical assistance and Jó for helpful discussions. We also thank Daniela Alviano, Sergio Fracalanzza, and Allen Hagler for providing strains of Candida spp.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aerts, A. M., I. E. Francois, E. M. Meert, Q. T. Li, B. P. Cammue, and K. Thevissen. 2007. The antifungal activity of RsAFP2, a plant defensin from Raphanus sativus, involves the induction of reactive oxygen species in Candida albicans. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 13:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbosa, F. M., S. Daffre, R. A. Maldonado, A. Miranda, L. Nimrichter, and M. L. Rodrigues. 2007. Gomesin, a peptide produced by the spider Acanthoscurria gomesiana, is a potent anticryptococcal agent that acts in synergism with fluconazole. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 274:279-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barns, S. M., D. J. Lane, M. L. Sogin, C. Bibeau, and W. G. Weisburg. 1991. Evolutionary relationships among pathogenic Candida species and relatives. J. Bacteriol. 173:2250-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barreto-Bergter, E., M. R. Pinto, and M. L. Rodrigues. 2004. Structure and biological functions of fungal cerebrosides. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 76:67-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemons, K. V., and D. A. Stevens. 2001. Efficacy of the partricin derivative SPA-S-753 against systemic murine candidosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:183-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins, B. E., L. J. Yang, and R. L. Schnaar. 2000. Lectin-mediated cell adhesion to immobilized glycosphingolipids. Methods Enzymol. 312:438-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva, A. F., M. L. Rodrigues, S. E. Farias, I. C. Almeida, M. R. Pinto, and E. Barreto-Bergter. 2004. Glucosylceramides in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides are involved in the differentiation of conidia into mycelial cells. FEBS Lett. 561:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enoch, D. A., H. A. Ludlam, and N. M. Brown. 2006. Invasive fungal infections: a review of epidemiology and management options. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:809-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folch, J., M. Lees, and G. H. Sloane Stanley. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226:497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graybill, J. R., L. K. Najvar, J. D. Holmberg, A. Correa, and M. F. Luther. 1995. Fluconazole treatment of Candida albicans infection in mice: does in vitro susceptibility predict in vivo response? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2197-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendriks, L., A. Goris, Y. Van de Peer, J. M. Neefs, M. Vancanneyt, K. Kersters, G. L. Hennebert, and R. De Wachter. 1991. Phylogenetic analysis of five medically important Candida species as deduced on the basis of small ribosomal subunit RNA sequences. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:1223-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levery, S. B., M. Momany, R. Lindsey, M. S. Toledo, J. A. Shayman, M. Fuller, K. Brooks, R. L. Doong, A. H. Straus, and H. K. Takahashi. 2002. Disruption of the glucosylceramide biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus by inhibitors of UDP-Glc:ceramide glucosyltransferase strongly affects spore germination, cell cycle, and hyphal growth. FEBS Lett. 525:59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacCallum, D. M., and F. C. Odds. 2004. Need for early antifungal treatment confirmed in experimental disseminated Candida albicans infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4911-4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nimrichter, L., E. Barreto-Bergter, R. R. Mendonca-Filho, L. F. Kneipp, M. T. Mazzi, P. Salve, S. E. Farias, R. Wait, C. S. Alviano, and M. L. Rodrigues. 2004. A monoclonal antibody to glucosylceramide inhibits the growth of Fonsecaea pedrosoi and enhances the antifungal action of mouse macrophages. Microbes Infect. 6:657-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nimrichter, L., M. D. Cerqueira, E. A. Leitao, K. Miranda, E. S. Nakayasu, S. R. Almeida, I. C. Almeida, C. S. Alviano, E. Barreto-Bergter, and M. L. Rodrigues. 2005. Structure, cellular distribution, antigenicity, and biological functions of Fonsecaea pedrosoi ceramide monohexosides. Infect. Immun. 73:7860-7868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okawa, Y., M. Miyauchi, S. Takahashi, and H. Kobayashi. 2007. Comparison of pathogenicity of various Candida albicans and C. stellatoidea strains. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30:1870-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto, M. R., M. L. Rodrigues, L. R. Travassos, R. M. Haido, R. Wait, and E. Barreto-Bergter. 2002. Characterization of glucosylceramides in Pseudallescheria boydii and their involvement in fungal differentiation. Glycobiology 12:251-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramamoorthy, V., E. B. Cahoon, J. Li, M. Thokala, R. E. Minto, and D. M. Shah. 2007. Glucosylceramide synthase is essential for alfalfa defensin-mediated growth inhibition but not for pathogenicity of Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Microbiol. 66:771-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rittershaus, P. C., T. B. Kechichian, J. C. Allegood, A. H. Merrill, Jr., M. Hennig, C. Luberto, and M. Del Poeta. 2006. Glucosylceramide synthase is an essential regulator of pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Investig. 116:1651-1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigues, M. L., L. Shi, E. Barreto-Bergter, L. Nimrichter, S. E. Farias, E. G. Rodrigues, L. R. Travassos, and J. D. Nosanchuk. 2007. Monoclonal antibody to fungal glucosylceramide protects mice against lethal Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:1372-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigues, M. L., L. R. Travassos, K. R. Miranda, A. J. Franzen, S. Rozental, W. de Souza, C. S. Alviano, and E. Barreto-Bergter. 2000. Human antibodies against a purified glucosylceramide from Cryptococcus neoformans inhibit cell budding and fungal growth. Infect. Immun. 68:7049-7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers, T. R. 2006. Antifungal drug resistance: limited data, dramatic impact? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27(Suppl. 1):7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito, K., N. Takakuwa, M. Ohnishi, and Y. Oda. 2006. Presence of glucosylceramide in yeast and its relation to alkali tolerance of yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 71:515-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnaar, R. L., and L. K. Needham. 1994. Thin-layer chromatography of glycosphingolipids. Methods Enzymol. 230:371-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terras, F. R., H. M. Schoofs, M. F. De Bolle, F. Van Leuven, S. B. Rees, J. Vanderleyden, B. P. Cammue, and W. F. Broekaert. 1992. Analysis of two novel classes of plant antifungal proteins from radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seeds. J. Biol. Chem. 267:15301-15309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thevissen, K., H. H. Kristensen, B. P. Thomma, B. P. Cammue, and I. E. Francois. 2007. Therapeutic potential of antifungal plant and insect defensins. Drug Discov. Today 12:966-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thevissen, K., D. C. Warnecke, I. E. Francois, M. Leipelt, E. Heinz, C. Ott, U. Zahringer, B. P. Thomma, K. K. Ferket, and B. P. Cammue. 2004. Defensins from insects and plants interact with fungal glucosylceramides. J. Biol. Chem. 279:3900-3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]