Abstract

The major human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype circulating in Brazil is B, followed by F and C. We have genotyped 882 samples from Brazilian patients for whom highly active antiretroviral therapy failed, and we found subtype B and the unique recombinant B/F1 forms circulating. Due to codon usage variation, there is a significantly lower incidence of the substitutions L210W, Q151M, and F116Y in subtype F1 isolates than in the subtype B counterparts.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) presents a noticeable genetic diversity which allows for its classification into several groups, subtypes, sub-subtypes, and circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) (34). A global genetic analysis of HIV-1 could segregate this lentivirus into three main groups (M, N, and O). Group M is the major group causing the AIDS pandemic and includes most of the known isolates, and groups N and O include a low number of isolates coming from West Africa (19). Subtype F is spread in Africa, Europe, and South America. Subtype F was further divided into three subgroups, F1, F2, and F3 (2). Subgroup F1 includes some African strains clustered with previously described strains from Brazil, South America, and Romania, suggesting an African origin of the HIV-1 epidemic in these countries. Subgroups F2 and F3 include samples from Cameroon and Central African Republic, respectively (3). Later analysis of a collection of isolates from Central African Republic and other central African countries made clear that subgroup F3 could be considered a new subtype named K (6, 36).

Brazil exhibits a heterogeneous HIV-1 subtype distribution (3, 4, 5, 10, 30) compared to that in the United States. The major virus subtype is B, accounting for 70 to 80% of infections. The main non-B isolate belongs to subtype F1 (10 to 20%), together with mosaic sequences between subtypes B and F1. Subtype C isolates are prevalent in southern states, with a relatively high proportion (30 to 60%), accounting for the main non-B isolate in this region. In summary, subtype F and its mosaic forms and CRFs are the major non-B strains circulating in Brazil (3, 4, 5, 10, 30) and South America (7, 12, 19, 29), accounting for approximately 10 to 20% of non-B virus infections for this continent.

Analysis of the Brazilian HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) sequences demonstrated that the subtype F consensus sequence differs from the U.S. and E35D Brazilian subtype B virus consensus sequences in eight positions in protease (PR) protein (I15V, M36I, R41K, R57K, Q61N, L63P, and L89M) and 11 positions in the T39A RT palm-finger region (V35T, E40D, D131E, I135L, S162Y, K173T, Q174K, T200A, Q207A, and R211K). An increasing amount of experimental evidence suggested that different HIV-1 subtypes might exhibit different biological behaviors and consequently might respond differently to diagnostic, immunologic, and therapeutic interventions (16, 21, 28). Moreover, recent studies identified subtype-specific differences in viral susceptibility to specific drugs (1, 15) and in signature mutations selected by treatment (17). An important issue in this field is that HIV-1 subtypes may differ in the rate of fixation of mutations that confer drug resistance in individuals undergoing antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. In fact, this was a question recently addressed in two reports of subtype C virus found in Israel and Brazil (14, 33), showing differences in the number of protease inhibitor (PI)-associated mutations accumulated in subtype C isolates from patients undergoing highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens. Another important point is that specific drug resistance mutation (DRM) profiles found in different virus subtypes could be influenced by different codon usage (24, 27), as well as the phenotypic impact of different DRMs in different subtype backgrounds found in viral enzymes (16, 35).

Brazil has a history of universal and free access to ARV therapy since 1995 (23), and most ARV drugs prescribed in developed countries are available in the public sector in this country. This fact makes Brazil an appropriate setting for comparing the rate of fixation of mutations conferring drug resistance under specific ARV drug class exposure to B and non-B subtype isolates. In this work, we selected the third biggest southeastern state of Brazil, Minas Gerais, in which to study biological properties of subtype F isolates. This site was chosen due to the high proportion of distribution of subtypes B and F circulating in individuals attending the same AIDS clinics and sharing the same social and demographic profiles.

In this study, whole-blood samples were collected between March 2002 and December 2006 from 882 HIV-1 infection-treated patients for whom HAART was failing and who were attending AIDS clinics located throughout the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. All patients had been followed at outpatient clinics by the public health system and were engaged in the policy of freely accessing ARV drugs sponsored by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The genotyping resistance test was centralized at the Molecular Biology Laboratory, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, and was performed in patients that showed at least two therapeutic regimen failures, characterized by the persistence of higher viral load counts after continuous use of three or more ARV drugs, including at least one PI. The study was approved by the Brazilian National Committee for Ethics in Research (project Conep 2857).

A ViroSeq HIV-1 genotyping system (Celera Diagnostic; Abbott Laboratories) was used for the identification of resistance-associated mutations in the HIV-1 polymerase (pol) gene according to the manufacturer's protocol. All sequences obtained from samples were subjected to quality control assessments using Blast-Renageno resistance analysis software (http://www.aids.gov.br/) to exclude sample mix-ups or contamination. The genetic subtypes were determined using the 1.3-kb final edited sequence (297 nucleotides from PR and the first 1,003 nucleotides from RT). Two tools were used for subtype evaluation. First, the sequences were submitted to a REGA HIV subtyping tool available at the BioAfrica website (http://www.bioafrica.net) (9), and then, phylogenetic analyses were done with MEGA version 3.1 software (25), using the neighbor-joining method with Kimura's two-parameter model. Briefly, the sequences were aligned using ClustalW together with RT subtype reference sequences obtained from the Los Alamos HIV database; trees were inferred with the bootstrap test, using 1,000 replicates. The amino acid sequences of RT (positions 1 to 335) and PR (positions 1 to 99) genes were deduced from the nucleic acid sequences and compared to a subtype B consensus sequence from the Stanford HIV RT and PR sequence databases (http://hivdb.stanford.edu/hiv/). Established drug resistance positions were defined by use of the International AIDS Society-USA expert panel mutations list. PR and RT substitutions were categorized as nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), and PI mutations.

Treated patients were grouped according to infection by HIV-1 subtype B and F. For each subtype, we determine the frequency of mutations for PI and NNRTI. Differences in frequencies of the two subtypes were compared by the chi-square test, and the Fisher exact test was used for cases where the expected number of mutations for at least one of the subtypes was below 5. A P value associated with analyses of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R environment software (http://www.r-project.org/).

Over 3 years, 882 samples were received at the Federal University of Minas Gerais genotyping laboratory and were genotyped. From 882 HIV-1-genotyped patients, we were able to classify 639 (72%) isolates as subtype B, followed by 182 (22.5%) subtype F isolates, and 56 (6.3%) mosaic isolates between subtypes B and F. The B/F mosaic variants showed different recombination patterns when both genomic regions (PR and RT) were analyzed. Twenty-four sequences showed evidence of subtype divergence such as PRF/RTB, and 21 sequences showed the profile PRB/RTF. The remaining mosaic strains (n = 11) were composed of different subtype segments (B/D, D/F, B/C, and A/G). Five (0.56%) samples were classified as subtypes C (n = 1) and K (n = 4). Overall, the subtype distribution pointed to a high prevalence of subtype B (72%) and subtype F1 isolates and their mosaic forms. A small proportion of other subtypes was found, composed of subtypes K and C. These subtype profiles were similar to those found in southeastern Brazilian big cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (7, 12, 19, 29), except for the high prevalence of prototypic subtype F1 isolates, which was four times higher in Minas Gerais state. Subtype F strains together with the B/F mosaic strains were homogeneously distributed along with all those of the state regions. It should be noted that we did several analyses with these B/F mosaic strains and found that they do not fit with any previous B/F CRFs reported for South America.

Minas Gerais state was divided into five regions (northeast, northeast, southeast, southwest, and the state capital, which can be considered central) based on sociogeographic characteristics. The subtype distribution among different state regions is shown in Table 1. We could not find any dramatic asymmetry in terms of subtype profile, with comparable proportions of subtype B and mosaic forms in all five state regions analyzed.

TABLE 1.

Subtype distribution in five major regions of Minas Gerais statea

| Macro regions (n) | Distribution of subtypes

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| % B | % F1 | % Mosaic forms | |

| Belo Horizonte (549) | 72 | 23 | 5 |

| Southwest (125) | 79 | 14 | 7 |

| Southeast (47) | 61 | 30 | 9 |

| Northwest (77) | 78 | 14 | 8 |

| Northeast (53) | 75 | 17 | 8 |

The five major regions of Minas Gerais state include the northeast, northwest, southeast, southwest, and the state capital Belo Horizonte.

The clinical and demographic data from patients included in this study are summarized in Table 2. We could not find any significant difference in gender, CD4 count, virus load levels, and use of a main ARV drug class when the patients were referred for genotype testing. Of note, there is a male gender ratio prevalence of 2:1 for individuals infected with prototypic virus subtypes B and F and a 1:1 ratio for the mosaic counterparts. Likewise, the time, number, and nature of previous and present HAART regimens were comparable when these three groups were analyzed. The main HAART drugs utilized in the first line were two NRTIs (AZT [zidovudine], 3TC [lamivudine], and d4T [stavudine]), and one NNRT (efavirenz), and the following rescue therapies were composed of four ARV regimens including ritonavir-boosted PI (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographic and clinical data from patients included in this study

| Subtype | Frequency % (n) | Gender (% females) | CD4 count (cells/mm3)a

|

Virus load (copy no. of RNA/mm3)

|

No. of ARV drugs used in the last HAART regimen

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median | Range | Mean ± SD | Median | Range | Thymidine analogs (AZT and d4T) (%) | Nevirapine (%) | Efavirenz (%) | PI (%) | |||

| B | 72.9 (639) | 30.2 | 273.2 ± 222.9 | 225 | 1-1,795 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 4.4 | 2.8-6.4 | 622 (93.8) | 66 (10.0) | 196 (29.6) | 403 (60.8) |

| F1 | 20.7 (181) | 35.9 | 291.4 ± 236.3 | 237.5 | 4-1,637 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.3 | 3.0-6.0 | 193 (95.1) | 21 (10.3) | 57 (28.1) | 120 (59.1) |

| Mosaic | 6.4 (56) | 48.2 | 383.4 ± 479.0 | 237 | 2-2,610 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 4.5 | 2.5-5.6 | 10 (100.0) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) |

| Total | 100 | 283.5 ± 249.1 | 228.5 | 1-2,610 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 4.4 | 2.5-6.4 | |||||

SD, standard deviation.

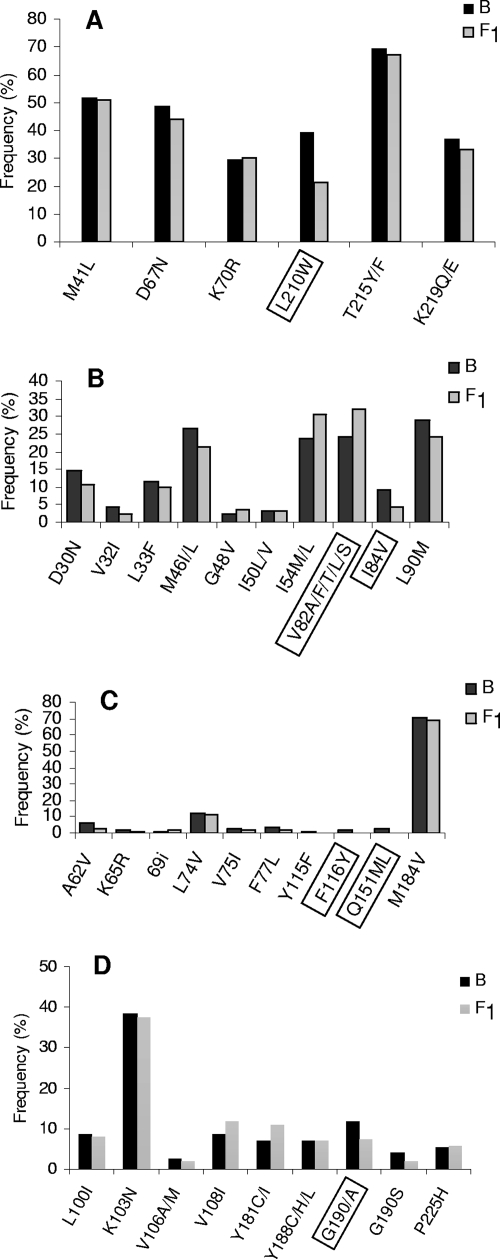

Based on drug resistance genotypic interpretation, 36 samples (4.10%) did not show any mutation associated with ARV resistance and were dropped from further analysis, as were the minority variants (C, K, and A/G) found in our database. The HIV-1 genotyping resistance profiles associated with the ARV drug distinguished according to the subtype B and F infections in protease and RT genomic regions are shown in Fig. 1. We focused solely on subtypes B and F and their mosaic forms, and, in terms of mutational analysis, all mosaic forms composed of subtype B and F segments were analyzed separately, based on the PR or RT subtype call composing the mosaic genome.

FIG. 1.

Histograms showing different DRM position frequencies in PR and RT enzymes. The DRM were divided into different drug class mutations such as TAM (A), primary PI (B), nucleoside-associated mutations (NAM) (C), and NNRTI (D). The mutations listed were based on the International AIDS Society-USA expert panel mutations list (13). Boxed positions are the ones showing significant frequency differences between subtype B and F1 isolates.

The most frequent amino acid substitution in the RT protein found in HIV-1-positive individuals for whom HAART was failing was M184V, followed by T215Y/F, M41L, D67N, L210W, K219Q/E, and K70R and other low-frequency substitutions (Q151M, V75 I, and F116Y). Overall, 42% of the individuals included in the present analysis showed an association with four NRTI resistance mutations (M184V, M41L, D67N, and T215Y/F), and we found seven isolates carrying insertions or deletions around codon 69 in our data set that were not related to subtype assignment (data not shown). When the data were segregated by subtype assignment, some differences in frequency could be noted. There is a significantly lower incidence of the substitutions L210W, Q151M, and F116Y in subtype F isolates than in the subtype B counterparts (Fig. 1A and B).

The K103N mutation was the main NNRTI resistance-associated mutation, followed by the mutations G190S/A, Y181C/I, P225H, and M230L. We noticed a significantly lower prevalence of mutation G190S/A in subtype F variants than in subtype B strains (Fig. 1C) and a higher accumulation of mutation G190A in subtype F1 than in subtype B counterparts. Conversely, mutation G190S is more prevalent in subtype B isolates from our data set (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid codon usage for five critical HIV-1 RT positions utilized by Brazilian subtype B and F1 isolatesa

| Subtypeb | Protease

|

Reverse transcriptase

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I54M/L

|

F116Y

|

Q151M/L

|

G190S/A

|

L210W

|

||||||

| Codon | % Used | Codon | % Used | Codon | % Used | Codon | % Used | Codon | % Used | |

| B wt | ATT(I) | 17.9 | TTT(F) | 90.14 | CAA(Q) | 5.3 | GGC(G) | 4.9 | TTA(L) | 25 |

| ATC(I) | 82.1 | TTC(F) | 9.38 | CAG(Q) | 94.7 | GGA(G) | 83.7 | TTG(L) | 74.5 | |

| GGG(G) | 11.1 | CTT(L) | 0.5 | |||||||

| B mutant | ATG(M) | 60 | TAT(Y) | 87 | ATG(M) | 100 | TCA (S) | 8 | TGG(W) | 100 |

| CTA(L) | 40 | TAC(Y) | 13 | GCA(S) | 89 | |||||

| GCG(A) | 3 | |||||||||

| F1 wt | ATT(I) | 2.4 | TTT(F) | 93.5 | CAA(Q) | 92.1 | GGC(G) | 16 | TTA(L) | 4.3 |

| ATC(I) | 97.6 | TTC(F) | 6.49 | CAG(Q) | 7.9 | GGA(G) | 84 | TTG(L) | 21.3 | |

| CTA(L) | 8.5 | |||||||||

| CTT(L) | 65.9 | |||||||||

| F1 mutant | ATG(M) | 100 | TAT(Y) | 0 | ATG(M) | 0 | AGC(S) | 6.7 | TGG(W) | 100 |

| TAC(Y) | 0 | GCA(S) | 14.9 | |||||||

| GCG(A) | 78.4 | |||||||||

Data in italics represent major codons and frequencies utilized by the drug-naive isolates. Data in boldface show the amino acid codons used by isolates carrying drug resistance mutations.

A subset of drug-naïve samples was selected from Brazilian patients infected with subtype B and F viruses and used as control; these were designated B wt and F wt, respectively.

The profile of resistance mutations associated with PI (Fig. 1D) was the minor mutation L63P, followed by L10F/R, M36I, A71V, and V77I. The most prevalent major mutation found in patients for whom ARV therapy was failing was V82A/F/T/L/S, followed by L90M, I54V, M46 I/L, D30N, I84V, I50V/L, and G48V. We could not find any major bias between the PI major mutation and the subtypes B and F, except for V82A/F/T/L/S, I54V, and I84V, which were significantly associated with subtype B isolates. Of note, drug resistance mutations were found in 95.9% of patients analyzed, and their profiles were in accordance with the drug regimens these individuals underwent. The major mutation profile found in RT sequence (M184V, M41L, D67N, and T215Y/F) was related to a higher exposure to thymidine analogs and 3TC. Conversely, the high proportion of the K103N mutation found in our data set reflects the high proportion of patients for whom NNRTI regimens containing efavirenz and nevirapine were failing. The major protease mutations found were V82A/F/T/L/S and L90M, mirroring the usage of indinavir, lopinavir, and nelfinavir in previous and present PI regimens prescribed.

One of the major findings in this study was the unbalanced incidence of the thymidine analog mutation (TAM) L210W and the Q151M complex in subtype B and F1 viruses in patients for whom regimens were failing. HIV-1 RT (TAM), selected by AZT and d4T, can cause reduced susceptibility to all approved NRTI. TAM can occur in two distinct genotypic patterns (M41L-D67N-L210W-T215Y or D67N-K70R-T215F-K219Q/E/N), where only the latter pattern causes reduced susceptibility to tenofovir in vitro and in patients. The L210W, T215Y/F, and M41L mutations usually are positively associated in NRTI-resistant clinical isolates (8, 26). Moreover, a negative correlation between the K70R and L210W mutations has been observed in subtype B isolates (20, 37). This fact points out the importance of L210W in tenofovir cross-resistance in patients for whom thymidine analog regimens are failing. Likewise, the frequency of Q151M-mediated multinucleoside drug resistance has been 0 to 10% in patients receiving the AZT-plus-didanosine (ddI) combination therapy, and these mutations include V75I, F77L, F116Y, and Q151M. The Q151M mutation is the first to develop and confer partial resistance to AZT, ddI, zalcitabine, and stavudine (11, 31, 32). The V75I, F77L, and F116Y mutations do not affect drug susceptibility by themselves, but, when added to Q151M, they confer increased resistance to AZT, ddI, zalcitabine, and stavudine and limited cross-resistance to 3TC (22). The Q151M mutation plays a central role in promoting both AZTTP and dideoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (ddNTP) discrimination. Interestingly, Q151M alone promotes a much greater resistance to AZTTP than to ddNTPs, and the subsequent appearance of the other mutations of the Q151M complex are at the benefit of ddATP resistance almost exclusively (23).

The analyses in the present study showed that two drug resistance-related RT residues, 210 and 151, have a higher genetic barrier to the acquisition of the resistance codons in subtype F1 than in subtype B, both the mutations of which are important determinants of nucleoside analogue susceptibility. It is noteworthy that these two resistance codons [W (TGG) and M (ATG)] are not degenerate and, therefore, underpinned the pathway to reach the mutant codon. In fact, when the minimal nucleotide changes necessary to acquire seven DRM (L210W, Q151M, F116Y, G190S/A, V82A/F/T/L/S, I54V, and I84V) with incidence asymmetry between subtypes B and F1 in our data set were compared, two mutations (Q151M and L210W) seemed to have different requirements for appearance in subtype F1 viruses than in their subtype B virus counterpart. In both instances, an extra transition event was necessary to generate the resistant amino acid in subtype F1. For the Q151M mutation, two transversion and one transition events are necessary to take the subtype F1 codon CAA to ATG, whereas for the B isolates, only two transversions are necessary (CAG→ATG). Similarly, for the L210W mutation, one transversion and one transition are necessary in subtype F1 virus, whereas only one transversion is required for other subtypes (Table 2). All remaining wild-type codons showed the same evolutionary cost, in terms of the number and nature of nucleotide substitutions, of changing to mutant codons in subtype B and F1 isolates. These results suggest that a higher genetic barrier may play a role in some DRM acquisitions in the RT gene from different subtypes. The higher genetic barrier to acquiring the L210W and Q151M mutations in subtype F1 was predicted (24). However, this is the first demonstration of this phenomenon in a large treatment cohort. These results suggest that a higher genetic barrier plays an important role in some DRM acquisitions in the RT gene from subtypes B and F, driving the selection of different resistant profiles with similar ARV regimens. There are several reports regarding different biological properties from non-B HIV-1 subtype isolates. PR mutation L90M occurs more frequently in non-B subtypes, whereas the D30N mutation occurs less frequently in non-B subtypes (6). Similarly, the RT K65R mutation has been reported to occur more frequently in subtype C than in other subtypes, owing to the consensus codon for K65 in subtype C (AAG rather than AAA), imposing a lower genetic barrier for this variant (17).

The low prevalence of the L210W and Q151M mutations in subtype F1 isolates found here highlighted the importance of the differences in codon usage in different subtypes in the mutational pathway for different HIV-1 subtypes. The same kind of studies need to be extended to other group M subtypes.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by Brazilian AIDS program (Ministerio da Saude, Brazil), CNPq, and FAPERJ.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abecasis, A. B., K. Deforche, J. Snoeck, L. T. Bacheler, P. McKenna, A. P. Carvalho, P. Gomes, R. J. Camacho, and A. M. Vandamme. 2005. Protease mutation M89I/V is linked to therapy failure in patients infected with the HIV-1 non-B subtypes C, F or G. AIDS 19:1799-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apetrei, C., D. Descamps, G. Collin, I. Loussert-Ajaka, F. Damond, M. Duca, F. Simon, and F. Brun-Vézinet. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype F reverse transcriptase sequence and drug susceptibility. J. Virol. 72:3534-3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barreto, C. C., A. Nishyia, L. V. Araújo, J. E. Ferreira, M. P. Busch, and E. C. Sabino. 2006. Trends in antiretroviral drug resistance and clade distributions among HIV-1-infected blood donors in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 41:338-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan, C. A., C. Brites, P. Bodelle, A. Golden, J. Hackett, Jr., V. Holzmayer, P. Swanson, A. Vallari, J. Yamaguchi, S. Devare, C. Pedroso, A. Ramos, and R. Badaro.. 2007. HIV-1 strains identified in Brazilian blood donors: significant prevalence of B/F1 recombinants. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 23:1434-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brindeiro, R. M., R. S. Diaz, E. C. Sabino, M. G. Morgado, I. L. Pires, L. Brigido, M. C. Dantas, D. Barreira, P. R. Teixeira, and A. Tanuri for the Brazilian network for drug resistance surveillance.. 2003. Brazilian network for HIV drug resistance surveillance (HIV-BResNet): a survey of chronically infected individuals. AIDS 17:1063-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cane, P. A., A. de Ruiter, P. Rice, R. Wiselka, R. Fox, and D. Pillay. 2001. Resistance-associated mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C protease gene from treated and untreated patients in the United Kingdom. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2652-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrion, G., L. Eyzaguirre, S. M. Montano, V. Laguna-Torres, M. Serra, N. Aguayo, M. M. Avila, D. Ruchansky, M. A. Pando, J. Vinoles, J. Perez, A. Barboza, G. Chauca, A. Romero, A. Galeano, P. J. Blair, M. Weissenbacher, D. L. Birx, J. L. Sanchez, J. G. Olson, and J. K. Carr. 2004. Documentation of subtype C HIV type 1 strains in Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 20:1022-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coakley, E. P., J. M. Gillis, and S. M. Hammer. 2000. Phenotypic and genotypic resistance patterns of HIV-1 isolates derived from individuals treated with didanosine and stavudine. AIDS 14:F9-F15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Oliveira, T., K. Deforche, S. Cassol, M. Salminen, D. Paraskevis, C. Seebregts, J. Snoeck, E. J. van Rensburg, A. M. J. Wensing, D. A. van de Vijver, C. A. Boucher, R. Camacho, and A.-M. Vandamme.. 2005. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics 21:3797-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Sá Filho, D. J., M. C. Sucupira, M. M. Caseiro, E. C. Sabino, R. S. Diaz, and L. M. Janini. 2006. Identification of two HIV type 1 circulating recombinant forms in Brazil. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 22:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deval, J., B. Selmi, J. Boretto, M. P. Egloff, C. Guerreiro, S. Sarfati, and B. Canard. 2002. The molecular mechanism of multidrug resistance by the Q151M human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and its suppression using alpha-boranophosphate nucleotide analogues. J. Biol. Chem. 277:42097-42104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilernia, D. A., A. M. Gomez, L. Lourtau, R. Marone, M. H. Losso, H. Salomón, and M. Gómez-Carrillo. 2007. HIV type 1 genetic diversity surveillance among newly diagnosed individuals from 2003 to 2005 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 23:1201-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doualla-Bell, F., A. Avalos, B. Brenner, T. Gaolathe, M. Mine, S. Gaseitsiwe, M. Oliveira, D. Moisi, N. Ndwapi, H. Moffat, M. Essex, and M. A. Wainberg. 2006. High prevalence of the K65R mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C isolates from infected patients in Botswana treated with didanosine-based regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4182-4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumans, A. T., M. A. Soares, E. S. Machado, S. Hué, R. M. Brindeiro, D. Pillay, and A. Tanuri. 2004. Synonymous genetic polymorphisms within Brazilian human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 subtypes may influence mutational routes to drug resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1232-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez, L. M., R. M. Brindeiro, R. S. Aguiar, H. S. Pereira, C. M. Abreu, M. A. Soares, and A. Tanuri. 2004. Impact of nelfinavir resistance mutations on in vitro phenotype, fitness and replication capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type with B and C proteases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3552-3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez, L. M. F., R. M. Brindeiro, M. Tarin, A. Calazans, M. A. Soares, S. Cassol, and A. Tanuri. 2003. The subtype C of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease presents an in vitro hypersusceptibility to protease inhibitor Lopinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2817-2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman, Z., V. Istomin, D. Averbuch, M. Lorber, K. Risenberg, I. Levi, M. Chowers, M. Burke, N. Bar-Yaacov, J. M. Schapiro, and Israel AIDS Multi-Center Study Group.. 2004. Genetic variation at NNRTI resistance-associated positions in patients infected with HIV-1 subtype C. AIDS 18:909-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemelaar, J., E. Gouws, P. D. Ghys, and S. Osmanov. 2006. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetics subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS 20:W13-W23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hierholzer, J., S. Montano, M. Hoelscher, M. Negrete, M. Hierholzer, M. M. Avila, M. G. Carrillo, J. C. Russi, J. Vinoles, A. Alava, M. E. Acosta, A. Gianella, R. Andrade, J. L. Sanchez, G. Carrion, J. L. Sanchez, K. Russell, M. Robb, D. Birx, F. McCutchan, and J. K. Carr. 2002. Molecular epidemiology of HIV type 1 in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Argentina. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 18:1339-1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iversen, A. K. N., R. W. Shafer, K. Wehrly, M. A. Winters, J. I. Mullins, B. Chesebro, and T. C. Merigan.. 1996. Multidrug-resistant HIV-1 strains resulting from combination antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 70:1086-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeeninga, R. E., M. Hoogenkamp, M. Armand-Ugon, M. de Baar, K. Verhoef, and B. Berkhout. 2000. Functional differences between the long terminal repeat transcriptional promoters of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes A through G. J. Virol. 74:3740-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, V. A., F. Brun-Vezinet, B. Clotet, H. F. Gunthard, D. R. Kuritzkes, D. Pillay, J. M. Schapiro, and D. D. Richman. 2008. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: spring 2008. Top. HIV Med. 16:62-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei.. 2004. MEGA 3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinformatics 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loemba, H., B. Brenner, M. A. Parniak, S. Ma'ayan, B. Spira, D. Moisi, M. Oliveira, M. Detorio, and M. A. Wainberg. 2002. Genetic divergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Ethiopian clade C reverse transcriptase (RT) and rapid development of resistance against nonnucleoside inhibitors of RT. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2087-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, M. D., N. A. Margot, K. Hertogs, B. Larder, and V. Miller. 2001. Antiviral activity of tenofovir (PMPA) against nucleoside-resistant clinical HIV samples. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 20:1025-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, V., and B. Larder. 2001. Mutational patterns in the HIV genome and cross-resistance following nucleoside and nucleotide analogue drug exposure. Antivir. Ther. 6:25-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poveda, E., de-Mendoza, C., N. Parkin, S. Choe, P. García-Gasco, A. Corral, and V. Soriano. 2008. Evidence for different susceptibility to tipranavir and darunavir in patients infected with distinct HIV-1 subtypes. AIDS 22:611-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renjifo, B., P. Gilbert, B. Chaplin, G. Msamanga, D. Mwakagile, G. Msamanga, W. Fawzi, and M. Essex. 2004. Preferential in-utero transmission of HIV-1 subtype C compared to HIV-1 subtype A or D. AIDS 18:1629-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ríos, M., E. Delgado, L. Pérez-Alvarez, J. Fernández, P. Gálvez, E. V. de Parga, V. Yung, M. M. Thomson, and R. Nájera. 2007. Antiretroviral drug resistance and phylogenetic diversity of HIV-1 in Chile. J. Med. Virol. 79:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sá Ferreira, J. A., P. A. Brindeiro, S. Chequer-Fernandez, A. Tanuri, and M. G. Morgado. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 subtypes and antiretroviral drug resistance profiles among drug-naïve Brazilian blood donors. Transfusion 47:97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shafer, R. W., M. J. Kozal, M. A. Winters, A. K. Iversen, D. A. Katzenstein, M. V. Ragni, W. A. Meyer, 3rd, P. Gupta, S. Rasheed, R. Coombs, M. Katzman, S. Fiscus, and T. C. Merigan.. 1994. Combination therapy with zidovudine and didanosine selects for drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains with unique patterns of pol gene mutations. J. Infect. Dis. 169:722-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirasaka, T., M. F. Kavlick, T. Ueno, W. Y. Gao, E. Kojima, M. L. Alcaide, S. Chokekijchai, B. M. Roy, E. Arnold, R. Yarchoan, and H. Mitsuya.. 1995. Emergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with resistance to multiple dideoxynucleosides in patients receiving therapy with dideoxynucleosides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2398-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soares, E. A., A. F. Santos, T. M. Sousa, E. Sprinz, A. M. Martinez, J. Silveira, A. Tanuri, and M. A. Soares. 2007. Differential drug resistance acquisition in HIV-1 of subtypes B and C. PLoS ONE 2:e730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor, B. S., M. E. Sobieszczyk, F. E. McCutchan, and S. M. Hammer. 2008. The challenge of HIV-1 subtype diversity. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:1590-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teixeira, P. R., M. A. Vitoria, and J. Barcarolo. 2004. Antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: the Brazilian experience. AIDS 18(Suppl. 3):S5-S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Triques, K., A. Bourgeois, N. Vidal, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, C. Mulanga-Kabeya, N. Nzilambi, N. Torimiro, E. Saman, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2000. Near-full-length genome sequencing of divergent African HIV type 1 subtype F viruses leads to the identification of a new HIV type 1 subtype designated K. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 16:139-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yahi, N., C. Tamalet, C. Tourres, N. Tivoli, and J. Fantini. 2007. Mutation L210W of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in patients receiving combination therapy. Incidence, association with other mutations, and effects on the structure of mutated reverse transcriptase. J. Biomed. Sci. 7:507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]