Abstract

Previously we have characterized 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase (KSH), a key enzyme in microbial steroid degradation in Rhodococcus erythropolis strain SQ1, as a two-component iron-sulfur monooxygenase, comprised of the terminal oxygenase component KshA1 and the oxygenase-reductase component KshB. Deletion of the kshA1 gene resulted in the loss of the ability of mutant strain RG2 to grow on the steroid substrate 4-androstene-3,17-dione (AD). Here we report characteristics of a close KshA1 homologue, KshA2 of strain SQ1, sharing 60% identity at the amino acid level. Expression of the kshA2 gene in mutant strain RG2 restored growth on AD and ADD, indicating that kshA2 also encodes KSH activity. The functional complementation was shown to be dependent on the presence of kshB. Transcriptional analysis showed that expression of kshA2 is induced in parent strain R. erythropolis SQ1 in the presence of AD. However, promoter activity studies, using β-lactamase of Escherichia coli as a convenient transcription reporter protein for Rhodococcus, revealed that the kshA2 promoter in fact is highly induced in the presence of 9α-hydroxy-4-androstene-3,17-dione (9OHAD) or a metabolite thereof. Inactivation of kshA2 in parent strain SQ1 by unmarked gene deletion did not affect growth on 9OHAD, cholesterol, or cholic acid. We speculate that KshA2 plays a role in preventing accumulation of toxic intracellular concentrations of ADD during steroid catabolism. A third kshA homologue was additionally identified in a kshA1 kshA2 double gene deletion mutant strain of R. erythropolis SQ1. The developed degenerate PCR primers for kshA may be useful for isolation of kshA homologues from other (actino) bacteria.

Rhodococcus species display a wide range of metabolic capabilities, degrading a variety of environmental pollutants and transforming or synthesizing compounds with possible useful applications (3, 26, 30). A well-known feature of rhodococci is their ability to degrade a range of naturally occurring steroids, including cholesterol and phytosterols, e.g., β-sitosterol (26).

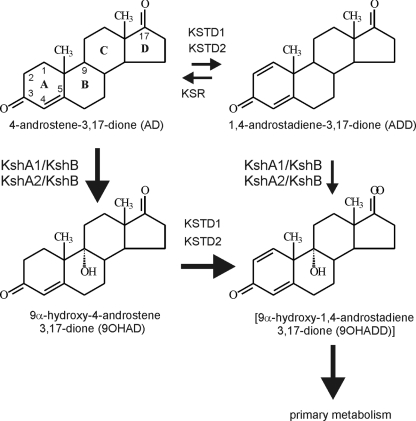

3-Ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase (KSH) is a key enzymatic step in the microbial steroid catabolic pathway, acting on 4- androstene-3,17-dione (AD) or 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione (ADD) (Fig. 1). Introduction of the 9α-hydroxyl moiety into the steroid polyheterocyclic ring structure, combined with steroid Δ1-dehydrogenation by 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase (KSTD), initiates steroid B-ring opening due to the formation of chemically unstable 9α-hydroxy-1,4-androstadiene-3,17- dione (9OHADD) (Fig. 1). KSH of Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 is a two-component class IA monooxygenase comprised of the terminal oxygenase KshA1 and the oxygenase reductase component KshB (23). Classification of nonheme oxygenases is based on the number of constituent components and the nature of their redox centers (2, 6, 8-10, 13). By definition, class I oxygenases are two-component enzymes composed of a reductase component and a terminal oxygenase component. The reductase component of oxygenases contains either a flavin mononucleotide (class IA) or a flavin adenine dinucleotide (class IB), an NAD binding domain, and a [2Fe-2S] redox center situated either N terminally (class IB) or C terminally (class IA).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the key enzyme steps involved in the degradation of the steroid intermediates AD, ADD, 9OHAD, and [9OHADD] during steroid ring degradation in R. erythropolis strain SQ1. KSTD1 and KSTD2 represent KSTDs in SQ1 (25). KshA1, KshA2, and KshB represent two multicomponent KSHs of SQ1 (24; this study). KSR represents 3-ketosteroid Δ1-reductase activity (see text). Thick arrows represent the proposed preferred route of steroid B-ring opening, aimed at keeping intracellular ADD concentrations low.

In previous work we have shown that gene inactivation of either kshA1 (mutant strain RG2) or kshB (mutant strain RG4) in parent strain R. erythropolis SQ1 results in loss of 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylation activity (24). Consequently, these mutants were unable to grow on both AD and ADD as sole carbon and energy sources. Such KSH mutant strains have industrial applications and can be used for the selective Δ1-dehydrogenation of pharmaceutically important steroids by biotransformation (28). Interestingly, growth of strain RG2 on cholesterol was comparable to that of parent strain SQ1. Biotransformation of cholesterol by cultures of strain RG2 did not result in accumulation of the expected steroid pathway intermediates (i.e., AD and ADD), indicative of the presence of at least one additional degradation pathway. By contrast, the inactivation of a single kshA gene by transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 was recently shown to cause accumulation of AD and ADD from β-sitosterol (1). We thus anticipated the presence of additional gene homologues of kshA in R. erythropolis. Recent studies have shown that rhodococci often contain multiple homologues of catabolic genes, thereby drastically improving their catabolic capabilities (26). The Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 genome sequence revealed the presence of up to four distinct pathways for steroid catabolism, each containing a kshA gene homologue (11, 27).

Currently, there is only very limited knowledge about KSH enzymes/genes, hampering industrial applications in the field of microbial steroid biotransformation. Studies of KSH enzymes furthermore are of medical importance. A gene cluster encoding the cholesterol catabolic pathway in R. jostii RHA1 was recently shown to be linked to the pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (27). M. tuberculosis is the causative agent of tuberculosis, causing millions of deaths every year. Notably, genes encoding enzymes involved in steroid ring opening, i.e., KSH, encoded by Rv3526, and KSTD, encoded by Rv3537, were identified as important for M. tuberculosis survival in macrophages (5, 17). The medical and applied aspects of KSH enzymes make them interesting enzymes to study in more detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Rhodococcus erythropolis parent strain SQ1 (16) and mutant strains were cultivated at 30°C and 200 rpm. Mutant strains RG2 (kshA1 mutant), RG4 (kshB mutant), and RG9 (kshA1 kstD kstD2 mutant) were previously described (24). Complex rich medium (LBP) contained 1% (wt/vol) Bacto peptone (Difco), 0.5% (wt/vol) yeast extract (BBL Becton Dickinson and Company), and 1% (wt/vol) NaCl (21). Mineral medium (pH 7) consisted of 4.65 g/liter K2HPO4, 1.5 g/liter NaH2PO4·H2O, 3 g/liter NH4Cl, 1 g/liter MgSO4·7H2O, and 1 ml/liter of fivefold-diluted Vishniac trace element solution (29). Cholesterol (1 g/liter) and cholic acid (1 g/liter) were added prior to autoclaving. Other steroids (0.5 g/liter) were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 50 mg/ml) and added to autoclaved medium. The sucrose sensitivities of Rhodococcus strains were tested on LBP agar supplemented with 10% (wt/vol) sucrose. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. Bacto agar (1.5% [wt/vol]; Difco) was added for growth on solid media.

PCR screening of genomic library using degenerate primers.

PCR was performed in a reaction mixture (50 μl) consisting of Tris-HCl (10 mM, pH 8) buffer, polymerase buffer, deoxynucleoside triphosphate (0.2 mM), DMSO (2%), KshAType-F primer (10 ng/μl), KshAType-R primer (10 ng/μl), and Taq or Vent polymerase (2 U) under the following conditions: 5 min at 95°C and 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 45 s at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C. The previously described genomic library of R. erythropolis RG1, a kstD mutant of parent strain SQ1, was used as template (24).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR experiments.

Rhodococcus cultures were grown in LBP medium (250 ml) until an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 2 was reached. When appropriate, cultures were induced for 4 h with steroids (0.5 g/liter) dissolved in DMSO. Following centrifugation (10 min, 7,300 × g, 4°C), the cell pellet was crushed by pestle and mortar in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use. Total RNA was subsequently isolated using the RNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen). Prior to reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR), the isolated total RNA was treated with a DNase I amplification-grade kit (Invitrogen, The Netherlands) for 15 min at room temperature. DNase I was heat inactivated for 10 min at 65°C. RT-PCR was performed with approximately 0.5 μg total RNA, determined on a GeneQuant spectrophotometer, using the SuperScript III Platinum One Step GRT-PCR system kit (Invitrogen, The Netherlands). All kits were used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNA made by the reverse transcriptase reaction (15 min at 50°C) was heated for 2 min at 95°C and used for PCR (40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C). Gene-specific primers used for the RT-PCR experiments are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

PCR oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Specificity | Amplicon size | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| KshAType-F | kshA homologue | 0.3 kb | TGYCCITTCCAYGAYTGGCGITGGGGIGG |

| KshAType-R | kshA homologue | TGIACGTAAAGAAGRTGIGCCATRTC | |

| KshA2-F | kshA2, kshA3 | 0.6 kb | CTCGATGCCTACTGCCGTCAC |

| KshA2-R | kshA2, kshA3 | CGGATAGTGGCAGTTGATCAAAAC | |

| KSHA2EX-F | kshA2 | 1,167 bp | GGCCATATGTTGACCACAGACGTGACGACC (NdeI) |

| KSHA2EX-R | GCCACTAGTTCACTGCGCTGCTCCTGCACG (SpeI) | ||

| RT-KSHA2-F | kshA2 | 469 bp | AGCCAGAGCGAATTGAAGGT |

| RT-KSHA2-R | ATGTCGTCGCGGTTGATACC | ||

| RT-KSTD1-F | kstD1 | 489 bp | CCAGGTGCAGGAACGCGCCG |

| RT-KSTD1-R | CGCCTTGATTCGCTGGGTTT | ||

| 16SRNA-RHODO-F | 16S rRNA | 427 bp | GTCTAATACCGGATATGACCTC |

| 16SRNA-RHODO-R | R. erythropolis (4) | GCAAGCNAGNAGTTGAGCTGCTGGT | |

| delKSHA2-R | Upstream kshA2 | NAb | TCGAATACTGGGGACACGAAGC |

| BLF | bla | 809 bp | GCGCATATGCACCCAGAAACGCTGGTGAAAG (NdeI) |

| BLR | GCGACTAGTTACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGAGGC (SpeI) |

I, inosine; Y, C+T; R, A+G; N, any base. Underlined nucleotide sequences indicate incorporated restriction sites.

NA, not applicable.

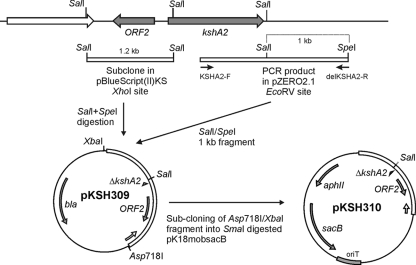

Construction of mutagenic plasmid pKSH310 for kshA2 unmarked gene deletion.

Gene deletion of kshA2 was achieved with pKSH310. A 1.2-kb SalI fragment of pAR1 (this study; see Results), representing the upstream region of kshA2, was cloned into XhoI-digested pBluescript (II) KS and named pKSH307. The PCR product (2.2 kb), obtained with primers KSHA2-F and delKSHA2-R (Table 1) using strain SQ1 genomic DNA, was cloned into EcoRV-digested pZeRO-2.1 vector (Invitrogen), yielding pKSH308. A 1-kb SalI/SpeI fragment of pKSH308, containing the downstream region of kshA2, was subsequently ligated into SalI/SpeI-digested pKSH307, thereby producing pKSH309. The two ligated fragments, harboring the kshA2 deletion, were then taken from pKSH309 by Asp718I/XbaI digestion, treated with Klenow enzyme, and cloned into SmaI-digested pK18mobsacB vector (18), thereby producing pKSH310 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Scheme of the genomic locus of kshA2 of R. erythropolis SQ1 and the cloning strategy to construct mutagenic plasmid pKSH310 used for unmarked kshA2 gene deletion in kshA1 mutant strain R. erythropolis RG2. Upstream of kshA2, another open reading frame (ORF2) is found encoding a protein with signatures of IclR-type transcriptional regulators.

Construction of unmarked gene deletion mutants RG23, RG24, and RG27.

Gene deletion mutants were constructed using the unmarked gene deletion method as described previously (23). The mutagenic plasmid pKSH310 was introduced into R. erythropolis SQ1 and RG2 by bacterial conjugation using E. coli S17-1 (19) to construct kshA2 mutant strain RG23 and kshA1 kshA2 mutant strain RG24. Mutagenic plasmid pKSH126 (23) was introduced into R. erythropolis RG4 to construct a kshA1 kshB mutant strain, RG27. Gene deletions were confirmed by PCR using gene-specific primers (Table 1).

Functional complementation experiments and construction of plasmids used.

Electrocompetent Rhodococcus cells were prepared and transformed as previously described (22). Rhodococcus transformants were replica plated onto mineral agar medium containing AD or ADD (0.5 g/liter) as sole carbon and energy source. Functional complementation for growth was scored after 3 days of incubation at 30°C. Plasmids pKSH312 and pKSH313 (Fig. 3), used for functional complementation experiments, were constructed as follows. The kshA2 gene was amplified by PCR using kshA2 primers KSHA2EX-F and KSHA2EX-R (Table 1) and subsequently cloned as an NdeI/SpeI fragment into NdeI/SpeI-digested pRESX (Fig. 3), resulting in plasmid pKSH312 (Fig. 3). Plasmid pKSH313, for simultaneous expression of kshA2 and kshB, was constructed by ligating a 1.46-kb NsiI/SpeI fragment of pKSH207 (24) containing kshB into NsiI/SpeI-digested pKSH312.

FIG. 3.

Derivatives of Rhodococcus expression vector pRESX used in this study for expression of kshA2 (pKSH312) and kshA2 and kshB (pKSH313) in gene deletion mutants of R. erythropolis SQ1. The pRESX vector contains the kstD1 promoter region providing constitutive gene expression in R. erythropolis (unpublished data).

Bioconversion experiments and analysis by gas chromatography and high-pressure liquid chromatography.

Steroid biotransformations and steroid analysis were performed (in duplicate) in shaking flasks containing 100-ml LBP-grown cultures of R. erythropolis strains essentially as previously described (22).

kshA2 promoter activity study and β-lactamase assay.

A leaderless bla gene (20) was amplified from pBluescript (II) KS by PCR using oligonucleotides BLF and BLR (Table 1). The obtained PCR product was digested with NdeI/SpeI and cloned into NdeI/SpeI-digested pRESX (Fig. 3). The leaderless bla gene, including rhodococcal ribosomal binding site sequence, was subsequently isolated from pRESX-BLAS following BstXI/SpeI digestion. The BstXI site was made blunt by T4 DNA polymerase treatment prior to SpeI digestion. The resulting DNA fragment was cloned under the control of the kshA2 promoter into EcoRV/SpeI-digested pKSH307, encompassing the 1.2-kb genomic SalI fragment (Fig. 2). Finally, the kshA2 promoter and truncated bla gene were cloned into pRESQ, resulting in pRESQ307BLAS used for the kshA2 promoter activity measurement. Rhodococcus cells harboring pRESQ307BLAS were grown in 100 ml glucose (20 mM) mineral medium supplemented with kanamycin (200 μg/ml) until the optical density at 600 nm reached 1.5 to 2.5. Induction (5 h) was performed using steroids at a final concentration of 0.25 g/liter where appropriate. β-Lactamase activity was measured at 37°C in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, using 0.5 mg/ml nitrocefin (ɛ486 = 15.6 × 103 M−1·cm−1) (14).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The R. erythropolis SQ1 sequence data for kshA2, ORF2, and kshA3 have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers EU656136 (kshA2 and ORF2) and FJ040874 (kshA3).

RESULTS

Designing degenerate PCR primers for identification of additional kshA homologues in kshA1 mutant Rhodococcus erythropolis strain RG2.

Degenerate kshA PCR primers KshAType-F and KshAType-R (Fig. 2; Table 1) were developed to screen the kshA1 gene deletion mutant strain RG2 for the presence of kshA gene homologues. The degenerate primers were designed on the conserved Rieske [2Fe-2S] domain (99 CPFHDWRWG 107 in KshA1) and the nonheme Fe(II) binding domain (191 DMAHFFYVH 199 in KshA1) using an alignment of amino acid sequences of KshA1 and putative actinomycetal orthologues identified by BLAST in databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi) (24). PCR experiments with these degenerate primers on total DNA of strain RG2 resulted in a PCR product of the expected size (0.3 kb). Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that part of a kshA homologue had been cloned that was very similar, but not identical, to that of kshA1; thus, it was designated kshA2.

Cloning of kshA2 from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1.

A genomic library of R. erythropolis strain RG1 (24) was screened using the degenerate kshA1 PCR primers, and a clone was isolated, designated pAR1, that contained the kshA2 gene. Nucleotide sequencing of this clone revealed that the 3′-end part of the kshA2 gene was not present. The genomic library was thus screened again by PCR using newly designed kshA2 primers KshA2-F and KshA2-R (Table 1) for an additional clone containing the 3′ end of kshA2. Primers KshA2-F and KshA2-R were designed on the conserved Rieske [2Fe-2S] domain (LDAYCRH) and the conserved VLINCHYP motif, respectively. The nucleotide sequence of the complete kshA2 gene (1,167 nucleotides) was determined from sequencing data of both kshA2-positive clones.

kshA2 (GC content, 58.2%) encodes a protein (KshA2) of 388 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 44 kDa. KshA2 displays highest overall amino acid sequence identity to Ro05811 of R. jostii RHA1 (11) (63%). High sequence identity was also found with KshA1 of R. erythropolis SQ1 (60%). The typical class IA terminal oxygenase Rieske type [2Fe-2S]R domain (C-X-H-X16-C-X2-H) and the mononuclear, nonheme Fe(II) binding motif (D/E-X3-D-X2-H-X4-H), previously identified in KshA1, were also fully conserved in KshA2.

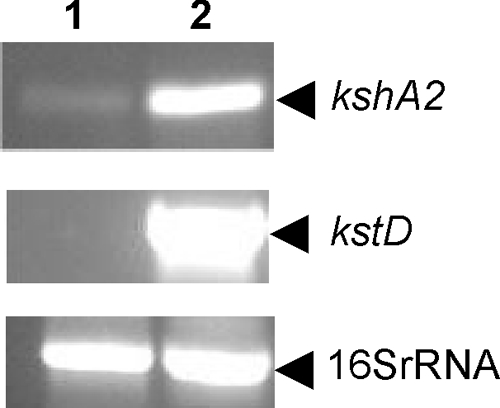

Transcriptional analysis revealed that kshA2 is steroid inducible.

To verify that kshA2 is involved in steroid catabolism in R. erythropolis strain SQ1, we performed transcriptional analysis of kshA2 gene expression by RT-PCR. Significant amounts of kshA2 RNA transcript were observed in cell cultures of parent strain SQ1 grown in complex medium (LBP) following AD induction (Fig. 4, lane 2). A very low level of kshA2 RNA transcript was found in control cell cultures without steroid induction (Fig. 4, lane 1). Thus, kshA2 is steroid inducible and most likely part of the steroid catabolic pathway. The kshA1 mutant strain RG2 is unable to grow on AD, apparently failing to use KshA2. KshA2 induction thus may require further conversion of AD, which is possible in wild-type strain SQ1 but not in strain RG2.

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional analysis of kshA2, kstD1 (positive control for AD induction), and 16S rRNA (control) by RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from noninduced cultures (lane 1) and AD-induced cultures of parent strain R. erythropolis SQ1 (lane 2). PCR primers used are RT-KSHA2-F and RT-KSHA2-R for kshA2, RT-KSTD1-F and RT-KSTD1-R for kstD1, and 16SRNA-RHODO-F and 16SRNA-RHODO-R for 16S rRNA (Table 1).

kshA2 encodes KSH activity and is under transcriptional control.

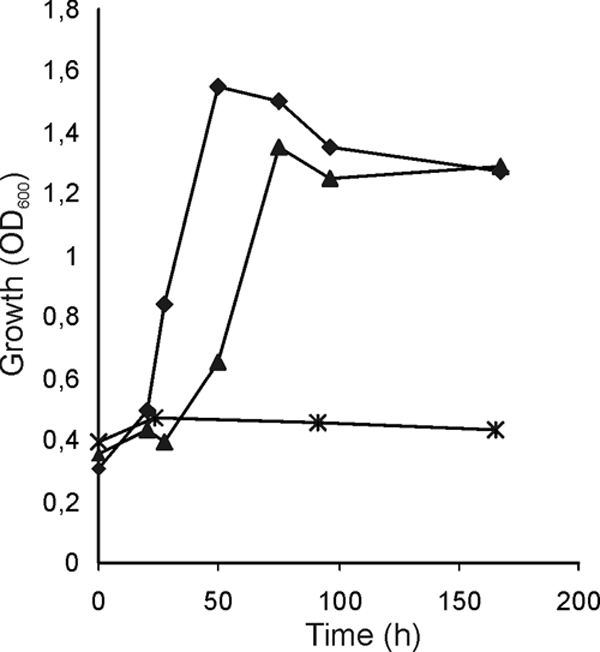

To determine whether kshA2 can functionally complement the AD growth-negative phenotype of kshA1 mutant strain RG2 and hence whether it encodes KSH activity, we forced expression of kshA2 in strain RG2 by putting kshA2 under the control of the promoter of kstD (22). The kstD promoter region, without its regulatory gene kstR, was cloned into pRESQ (24), yielding plasmid pRESX, and resulting in constitutive gene expression in R. erythropolis (Fig. 3) (unpublished data). The kshA2 gene was cloned into pRESX under the control of the kstD promoter, and the resulting plasmid pKSH312 (Fig. 3) was introduced into mutant strain RG2 by electrotransformation. Functional complementation of the AD growth-negative phenotype of strain RG2 harboring pKSH312 was observed (Fig. 5), confirming that kshA2 indeed is a kshA1 homologue, encoding a second terminal oxygenase component (KshA2) with KSH activity in R. erythropolis strain SQ1. The results furthermore suggest that the kshA2 promoter is under transcriptional control, since the kshA2 gene's own promoter does not promote growth of RG2 on AD (Fig. 5) although the presence of AD induces kshA2 expression in strain SQ1 (Fig. 4). Additionally, plasmid pKSH312 was introduced into the kshA1 kstD1 kstD2 triple gene deletion mutant strain RG9, unable to form 9OHAD from AD (24). Introduction of a copy of the kshA2 gene under the control of the kstD1 promoter restored the capability of strain RG9 to produce 9OHAD during AD biotransformation, as determined by high-pressure liquid chromatography/UV analysis. Thus, KshA2 displays AD 9α-hydroxylase activity.

FIG. 5.

Functional complementation of growth of kshA1 mutant R. erythropolis RG2 by kshA2 in AD mineral medium (average of duplicates). Growth curves represent parent strain (diamonds), kshA1 mutant strain RG2 (crosses), and RG2 harboring kshA2 on expression plasmid pKSH312 (Fig. 3) (triangles). OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

The kshA2 promoter is induced by 9OHAD.

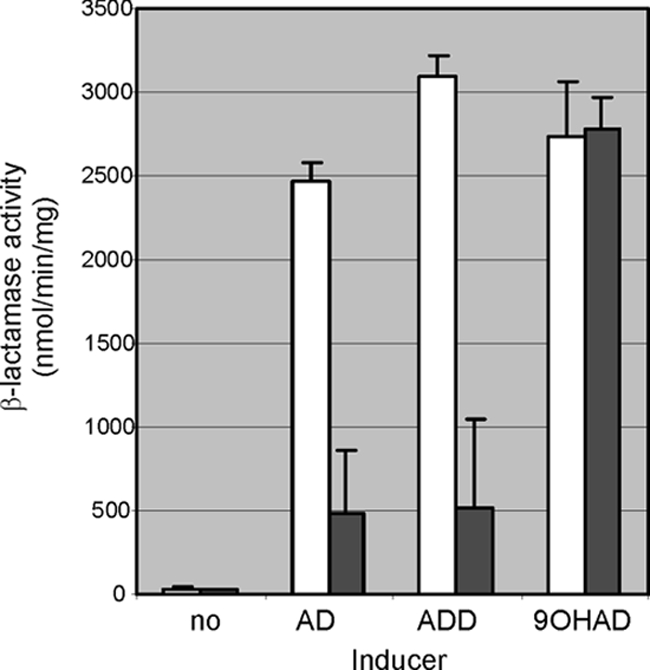

Paradoxically, the kshA1 mutant R. erythropolis strain RG2 cannot grow on AD as the sole carbon and energy source (24) despite the presence of a kshA2 homologue, encoding an enzyme with AD 9α-hydroxylase activity. To determine whether the kshA2 gene is actually transcribed in strain RG2, we checked kshA2 promoter activity by fusing the kshA2 promoter region to the bla gene, encoding β-lactamase activity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the use of E. coli β-lactamase as a convenient transcription reporter protein in Rhodococcus.

Noninduced cell cultures of parent strain SQ1 and kshA1 mutant strain RG2 showed very low kshA2 promoter activities (Fig. 6). Upon induction with AD, ADD, or 9OHAD, highly elevated levels of kshA2 promoter activity were observed with strain SQ1. Cell cultures of RG2, however, showed a different induction pattern. The kshA2 promoter activity in cell cultures of RG2 induced with 9OHAD was comparable to the levels found in parent strain SQ1 (Fig. 6), whereas RG2 cultures induced with AD or ADD showed greatly reduced (<20%) kshA2 promoter activities compared to those of parent strain SQ1. These results indicate that neither AD nor ADD, but 9OHAD (or a metabolite thereof), is the actual inducer of kshA2 expression. These observations also provide a plausible explanation for the AD/ADD growth-negative phenotype of the RG2 mutant. In strain RG2, kshA2 expression is not sufficiently induced in the presence of AD to allow growth on this steroid substrate as a sole carbon and energy source.

FIG. 6.

Promoter activity of kshA2 following induction by AD, ADD, or 9OHAD in parent strain SQ (open bars) and kshA1 mutant strain RG2 (solid bars), using leaderless β-lactamase as a reporter protein (14, 20).

Gene deletion of kshA2 does not affect growth on 9OHAD, cholesterol, or cholic acid.

Since kshA2 is induced predominantly by 9OHAD, we considered the possibility that the AD 9α-hydroxylase activity observed for KshA2 is not its main enzymatic activity. Instead, KshA2 might have an essential function in the further degradation of 9OHAD. To test this hypothesis, kshA2 gene deletion mutant strain RG23 and kshA1 kshA2 double gene deletion mutant strain RG24 were constructed from parent SQ1 and kshA1 mutant strain RG2, respectively. Growth of RG23 or RG24 in 9OHAD mineral medium was comparable to that of RG2 and parent strain SQ1, indicating that kshA2 is not essential for further 9OHAD degradation. Also growth of RG23 and RG24 on alternative classes of steroid substrates, i.e., sterols (cholesterol) and bile acids (cholic acid), as sole carbon and energy sources was similar to that of the parent strain. kshA2 therefore is not essential for the degradation of either of these steroid substrates. Growth of RG24 on cholic acid mineral medium was impaired compared to that of SQ1, but this was shown to be solely due to the inactivation of kshA1, since RG2 was impaired in growth on cholic acid to the same extent.

Functional complementation of RG2 by kshA2 is dependent on the presence of kshB.

KshA2 expectedly is part of a class IA two-component enzyme system, raising the question whether KshA2 could form an active enzyme complex with the previously identified KshB class IA oxygenase-reductase component (24) as part of a putative KshA2/KshB two-component enzyme. Alternatively, KshA2 may form a two-component enzyme system with a different, yet unknown, oxygenase-reductase component.

Functional complementation of growth of kshA1 mutant RG2, kshB mutant RG4 (24), and kshA1 kshB double mutant RG27 on ADD mineral agar plates by the kshA2 gene was therefore tested. Following the introduction of kshA2 expression plasmid pKSH312 (Fig. 3) into these strains, functional complementation of growth on ADD was observed only with mutant strain RG2, harboring an intact copy of the kshB gene. KshA2 thus indeed is active in the presence of the KshB component, indicating that KshB can function as an oxygenase-reductase for both KshA1 and KshA2 (Fig. 1). The formation of an active KshA2/KshB two-component enzyme system was furthermore supported by the observed functional complementation of growth on ADD mineral agar medium of strain RG27 harboring pKSH313, a pRESX derivative carrying both kshA2 and kshB (Fig. 3).

Identification of a third homologue, kshA3, in a kshA1 kshA2 double mutant.

In order to determine whether strain SQ1 contains more kshA homologues in addition to kshA1 and kshA2, PCR was performed on total DNA of the kshA1 kshA2 mutant strain RG24 using the degenerate kshA PCR primers (KshAType-F and KshAType-R, Table 1). Indeed, a PCR product of the expected size (0.3 kb) was obtained and nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that an additional kshA homologue had been amplified, designated kshA3. We additionally succeeded in obtaining a 0.6-kb PCR product of kshA3 from RG24 using PCR primers originally developed for kshA2 (KSHA2-F and KSHA2-R, Table 1). The nucleotide sequences of the 0.3-kb and 0.6-kb PCR products were 100% identical in the overlapping region, indicating that both PCR products originated from the same gene (kshA3). The deduced amino acid sequence of the partial KshA3 protein encoded by the 0.6-kb PCR product (199 amino acids) displayed the highest similarity with Ro04538 (89% identity over 199-amino-acid stretch) from R. jostii RHA1 (11). KshA3 is also highly similar to the same stretch of amino acids of KshA1 (69% identity) and KshA2 (66% identity). R. erythropolis strain SQ1 thus contains at least three kshA homologues.

DISCUSSION

Two enzymatic activities, i.e., KSTD and KSH, are involved in the opening of the steroid B-ring during microbial steroid degradation. In previous work, we have identified one KSH activity, comprised of KshA1 and KshB, and two KSTD activities, KSTD1 and KSTD2, in R. erythropolis SQ1 that are involved in the degradation of AD (22, 23, 24, 25). Here, we report the identification and characterization of a second terminal oxygenase component, KshA2, in R. erythropolis SQ1 as part of the AD catabolic pathway (Fig. 1).

The kshA2 gene codes for a second terminal oxygenase component, KshA2, in R. erythropolis SQ1 with AD 9α-hydroxylase activity. In parent strain SQ1, expression of kshA2 is induced by AD. However, analysis of induction of kshA2 promoter activity, using β-lactamase as a convenient reporter protein, showed that 9OHAD serves as a much better inducer than does AD or ADD. Thus, 9OHAD, or a metabolite thereof, is the actual inducer of kshA2 expression. The kshA2 promoter study also provided an explanation for the observation that kshA1 mutant strain RG2 is unable to grow on AD or ADD, despite the presence of a functional kshA2 gene. In RG2, kshA2 is unable to take over the function of kshA1, because expression of kshA2 is not sufficiently induced in the presence of AD or ADD and also because 9OHAD is not formed.

kshA2 clearly is under transcriptional control: kshA2 episomally expressed under the control of a constitutive promoter (kstD1) yielded KSH activity that could restore the growth of the mutant strain RG2 on AD. Interestingly, kshA2 is preceded by an open reading frame (ORF2) (Fig. 2), encoding a 238-amino-acid protein displaying similarity to IclR-type transcriptional regulators (ScanProsite, www.expasy.ch). The ORF2-encoded protein contains an IclR-type helix-turn-helix domain (PS51077) and an IclR-type effector domain (PS51078). The protein also displays similarity to the IclR-type regulator identified upstream of the bphC1 gene in Rhodococcus rhodochrous K37 and KsdR, a putative DNA binding regulatory protein of ksdD encoding KSTD in Arthrobacter simplex (12, 21). The bphC1 gene of R. rhodochrous K37 is induced by the steroid testosterone (21). Based on these similarities, ORF2 might encode a transcriptional regulator for kshA2 expression. Most IclR-type transcription regulators are repressors of specific catabolic genes in the absence of specific substrates, while excess of a specific effector triggers derepression (Prosite documentation PDOC00807, www.expasy.ch). If the ORF2-encoded protein indeed acts as a repressor of kshA2 expression, inactivation of ORF2 should restore growth of RG2 on AD. However, when we performed a gene deletion of ORF2 in R. erythropolis strain RG2, growth of the resulting double mutant on AD was not restored (data not shown). Thus, the ORF2-encoded protein most likely is not a repressor of kshA2 expression.

The terminal oxygenase KshA2 activity is observed only in the presence of KshB, suggesting that KshA2/KshB constitute a second KSH enzyme activity (KSH2), in addition to the KSH activity of KshA1/KshB in R. erythropolis SQ1. KshB has been classified as a class IA oxygenase-reductase (24). Therefore, we can classify KshA2 as a class IA terminal oxygenase. Strain SQ1 most likely contains only one oxygenase-reductase, KshB, supplying reducing equivalents to multiple terminal oxygenases. This is in agreement with the observed phenotype of kshB mutant RG4, which is fully blocked in AD and cholesterol degradation (24), likely due to a lack of supply of reducing equivalents toward KshA1, KshA2, and additional homologues, e.g., KshA3.

Inactivation of kshA2 did not result in blocked growth on 9OHAD, cholic acid, or cholesterol. The kshA2 gene thus does not have an essential role in the degradation of either of these different classes of steroids. Speculatively, KshA2 might play a role in limiting the metabolic flux through ADD during AD catabolism. Keeping the intracellular levels of ADD low by regulating KSTD and KSH activities would be advantageous to the cell, since ADD is known to have toxic effects (15). Interestingly, ADD biotransformation experiments with R. erythropolis cell cultures generally result in a temporal accumulation of AD (data not shown), indicating the presence of 3-ketosteroid Δ1-reductase activity (KSR, Fig. 1). Δ1-Reductase activity has also been observed in Mycobacterium sp. strain NRRL B-3805, and the activity increased significantly upon induction of cultures by ADD (7). The above-mentioned data suggest a preference for steroid catabolism via 9α-hydroxylated rather than Δ1-desaturated steroid pathway intermediates. Degradation of AD via the 9OHAD intermediate and not via the moderately toxic intermediate ADD would be beneficial to the cell, necessitating the activation of an additional KSH activity, i.e., KshA2 (Fig. 1).

A third kshA gene (kshA3) was successfully identified by PCR in kshA1 kshA2 mutant RG24 by using the developed degenerate primers for kshA1, indicating that these are suitable PCR primers for the amplification of kshA gene homologues. These primers can thus be used to screen for, and clone, additional kshA genes from other interesting (actino)bacteria. The KshA3 protein sequence displayed highest identity with Ro04538 from R. jostii RHA1. Interestingly, the ro04538 gene is part of the cholesterol catabolic gene cluster recently identified in R. jostii RHA1 (27), suggesting that kshA3 encodes the KSH oxygenase component involved in cholesterol catabolism in R. erythropolis SQ1.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by Schering-Plough (Oss, The Netherlands) and the University of Groningen.

We thank Kamila Rosłoniec for technical advice on the β-lactamase assay.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andor, A., A. Jekkel, D. A. Hopwood, F. Jeanplong, E. Ilkoy, A. Konya, I. Kurucz, and G. Ambrus. 2006. Generation of useful insertionally blocked sterol degradation pathway mutants of fast-growing mycobacteria and cloning, characterization, and expression of the terminal oxygenase of the 3- ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase in Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6554-6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batie, C. J., D. P. Ballou, and C. C. Correll. 1991. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase and related flavin-iron-sulfur containing electron transferases, p. 543-556. In F. Müller (ed.), Chemistry and biochemistry of flavoenzymes, vol. 3. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell, K. S., J. C. Philp, D. W. J. Aw, and N. Christofi. 1998. The genus Rhodococcus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85:195-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell, K. S., M. S. Kuyukina, S. Heidbrink, J. C. Philp, D. W. J. Aw, I. B. Ivshina, and N. Christofi. 1999. Identification and environmental detection of Rhodococcus species by 16S rDNA-targeted PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:472-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correll, C. C., C. J. Batie, D. P. Ballou, and M. L. Ludwig. 1992. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase: a modular structure for electron transfer from pyridine nucleotides to [2Fe-2S]. Science 258:1604-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goren, T., M. Harnik, S. Rimon, and Y. Aharonowitz. 1983. 1-Ene-steroid reductase of Mycobacterium sp. NRRL B3805. J. Steroid Biochem. 19:1789-1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harayama, S., and M. Kok. 1992. Functional and evolutionary relationships among diverse oxygenases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:565-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang, H., R. E. Parales, N. A. Lynch, and D. T. Gibson. 1996. Site-directed mutagenesis of conserved amino acids in the alpha subunit of toluene dioxygenase: potential mononuclear non-heme iron coordination sites. J. Bacteriol. 178:3133-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason, J. R., and R. Cammack. 1992. The electron-transport proteins of hydroxylating bacterial dioxygenases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46:277-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLeod, M. P., R. L. Warren, W. W. Hsiao, N. Araki, M. Myhre, C. Fernandes, D. Miyazawa, W. Wong, A. L. Lillquist, D. Wang, M. Dosanjh, H. Hara, A. Petrescu, R. D. Morin, G. Yang, J. M. Stott, J. E. Schein, H. Shin, D. Smailus, A. S. Siddiqui, M. A. Marra, S. J. Jones, R. Holt, F. S. Brinkman, K. Miyauchi, M. Fukuda, J. E. Davies, W. W. Mohn, and L. D. Eltis. 2006. The complete genome of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 provides insights into a catabolic powerhouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:15582-15587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molnár, I., K. P. Choi, M. Yamashita, and Y. Murooka. 1995. Molecular cloning, expression in Streptomyces lividans, and analysis of a gene cluster from Arthrobacter simplex encoding 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase, 3-ketosteroid-Δ5-isomerase and a hypothetical regulatory protein. Mol. Microbiol. 15:895-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakatsu, C. H., N. A. Straus, and R. C. Wyndham. 1995. The nucleotide sequence of the Tn5271 3-chlorobenzoate 3,4-dioxygenase genes (cbaAB) unites the class IA oxygenases in a single lineage. Microbiology 141:485-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Callaghan, C. H., A. Morris, S. M. Kirby, and A. H. Shingler. 1972. Novel method for detection of beta-lactamases by using a chromogenic cephalosporin substrate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1:283-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez, C., A. Falero, N. Llanes, B. R. Hung, M. E. Herve, A. Palmero, and E. Marti. 2003. Resistance to androstanes as an approach for androstandienedione yield enhancement in industrial mycobacteria. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 30:623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan, S., and E. R. Dabbs. 1993. Nocardioform arsenic resistance plasmid characterization and improved Rhodococcus cloning vectors. Plasmid 29:74-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rengarajan, J., B. R. Bloom, and E. J. Rubin. 2005. Genome-wide requirements for Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation and survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:8327-8332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutcliffe, J. G. 1978. Nucleotide sequence of the ampicillin resistance gene of Escherichia coli plasmid pBR322. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:3737-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taguchi, K., M. Motoyama, and T. Kudo. 2004. Multiplicity of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase genes in the Gram-positive polychlorinated biphenyl degrading bacterium Rhodococcus rhodochrous K37. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68:787-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Geize, R., G. I. Hessels, R. van Gerwen, J. W. Vrijbloed, P. van der Meijden, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2000. Targeted disruption of the kstD gene encoding a 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase isoenzyme of Rhodococcus erythropolis strain SQ1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2029-2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Geize, R., G. I. Hessels, R. van Gerwen, P. van der Meijden, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2001. Unmarked gene deletion mutagenesis of kstD, encoding 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 using sacB as counter-selectable marker. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:197-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Geize, R., G. I. Hessels, R. van Gerwen, P. van der Meijden, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2002. Molecular and functional characterization of kshA and kshB, encoding two components of 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase, a class IA monooxygenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1007-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Geize, R., G. I. Hessels, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2002. Molecular and functional characterization of the kstD2 gene of Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 encoding a second 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase isoenzyme. Microbiology 148:3285-3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Geize, R., and L. Dijkhuizen. 2004. Harnessing the catabolic diversity of rhodococci for environmental and biotechnological applications. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:255-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Geize, R., K. Yam, T. Heuser, M. H. Wilbrink, H. Hara, M. C. Anderton, E. Sim, L. Dijkhuizen, J. E. Davies, W. W. Mohn, and J. D. Eltis. 2007. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:1947-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Geize, R., P. van der Meijden, G. I. Hessels, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2003. Identification of 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase genes and microorganisms blocked in 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase activity. Patent WO 03/070925. Akzo Nobel N.V. (The Netherlands).

- 29.Vishniac, W., and M. Santer. 1957. The thiobacilli. Bacteriol. Rev. 21:195-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warhurst, A. M., and C. A. Fewson. 1994. Biotransformations catalyzed by the genus Rhodococcus. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 14:29-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]