Abstract

The importance of Ixodes ricinus in the transmission of tick-borne pathogens is well recognized in the United Kingdom and across Europe. However, the role of coexisting Ixodes species, such as the widely distributed species Ixodes trianguliceps, as alternative vectors for these pathogens has received little attention. This study aimed to assess the relative importance of I. ricinus and I. trianguliceps in the transmission of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia microti among United Kingdom field voles (Microtus agrestis), which serve as reservoir hosts for both pathogens. While all instars of I. trianguliceps feed exclusively on small mammals, I. ricinus adults feed primarily on larger hosts such as deer. The abundance of both tick species and pathogen infection prevalence in field voles were monitored at sites surrounded with fencing that excluded deer and at sites where deer were free to roam. As expected, fencing significantly reduced the larval burden of I. ricinus on field voles and the abundance of questing nymphs, but the larval burden of I. trianguliceps was not significantly affected. The prevalence of A. phagocytophilum and B. microti infections was not significantly affected by the presence of fencing, suggesting that I. trianguliceps is their principal vector. The prevalence of nymphal and adult ticks on field voles was also unaffected, indicating that relatively few non-larval I. ricinus ticks feed upon field voles. This study provides compelling evidence for the importance of I. trianguliceps in maintaining these enzootic tick-borne infections, while highlighting the potential for such infections to escape into alternative hosts via I. ricinus.

Wild rodents are important reservoirs of numerous tick-borne pathogens, including those that cause Lyme borreliosis, granulocytic anaplasmosis and babesiosis (32, 33). That rodent populations commonly exist at high densities and are infested with large numbers of the key vector species underlies this importance. In the United States and Europe, it is the broad-host-range tick species such as Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus, and Ixodes ricinus that are considered as key vector species, but rodents may be infested with more specialized ticks that solely utilize small mammals as hosts for all developmental stages, such as Ixodes trianguliceps and Ixodes spinipalpis (6, 26).

We have previously reported on the role of I. trianguliceps as a vector for Anaplasma phagocytophilum (4, 22), the causative agent of human anaplasmosis and tick-borne fever in livestock (7, 35), while previous studies had demonstrated its competence as a vector for Babesia microti (29, 36). More recently we reported that field voles (Microtus agrestis) in northern England are infested with both I. trianguliceps and I. ricinus (5), leading us to hypothesize, like others (13), that enzootic infections maintained in an I. trianguliceps-field vole cycle could escape into other hosts, including humans and domesticated animals, via I. ricinus. Furthermore, as I. ricinus nymphs and larvae feed concurrently upon field voles, it is feasible that I. ricinus plays a significant role in the transmission of infections between field voles, instead of merely acting as a bridge vector to other host species. The possibility of interrodent I. ricinus-mediated transmission clearly has important implications for the role of rodents in the epidemiology of tick-borne infections where I. trianguliceps is absent. The objective of our study was, therefore, to determine the relative importance of I. ricinus and I. trianguliceps as vectors for both A. phagocytophilum and B. microti in rodents by using field data derived from the study of field voles inhabiting grasslands within a large managed spruce plantation forest in northern England.

Although, when present, rodents serve as hosts for large numbers of immature I. ricinus, adult female ticks primarily take their blood meal from larger hosts such as deer or grazing livestock (21). Previous studies have reported that removal of such hosts can significantly reduce exophilic tick abundance (2, 3, 10, 25). In Kielder Forest, as in other managed forests, the economic implications of deer-induced damage are well-recognized and thus various countermeasures are employed. One such countermeasure is the creation of large fenced areas within the forest that are designed to exclude deer from new plantations. We hypothesized that the exclusion of deer from fenced sites within Kielder Forest would have a marked impact on the abundance of I. ricinus but little effect on I. trianguliceps abundance as adult females of this species take their blood meals from small mammals. Unlike deer, small mammals are not directly affected by fencing. This management method thus provided a useful system to investigate whether I. ricinus and I. trianguliceps individually or in concert are responsible for transmission of vector-borne zoonoses among field vole hosts in northern United Kingdom uplands.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study areas and sample collection.

The study was undertaken at locations within Kielder Forest, Northumberland, United Kingdom (55°13′N, 2°33′W), a conifer plantation covering 600 km2, between April and August in 2004 and 2005. Study sites were located within clear-cut areas created by the recent felling of trees where grasses (e.g., Deschampsia cespitosa Beauv. and Agrostis tenuis Sibth.), rushes (e.g., Juncus effusus), and bryophytes are the most abundant vegetation and where the field vole is the most common small mammal species, although small numbers of wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus), bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus), and common shrews (Sorex araneus) are also encountered (24). These field vole populations have been shown to undergo multiannual cycles in which densities can peak at >500 animals per hectare before crashing and subsequently recovering (19).

Eight sites were chosen, four of which were surrounded by 2-m-high fencing used to protect young trees from damage from browsing roe deer (the exclosures). Fencing at each of the exclosure sites had been in place for at least 3 years, so any potential effects on I. ricinus abundance would be well established. Exclosures varied in size from approximately 6 to 15 ha.

At each site, a 50-m-by-50-m small mammal trapping grid was established, where an Ugglan special multicapture trap (Grahnab, Marieholm, Sweden) was placed at 5-m intervals, yielding a total of 100 traps per grid. At the exclosure sites, grids were situated centrally and at least 25 m from the edge to reduce any “edge effect” resulting from inward movement by questing ticks. Upon first capture, each vole had a unique microchip transponder (AVID Systems) inserted subcutaneously, enabling it to be identified upon subsequent capture. Voles were then weighed, their sex and reproductive status were recorded, and a blood sample taken from the tail tip. They were then examined for ticks, with all larvae present being removed and stored in 70% ethanol for identification in the laboratory using standard keys (1, 31), before releasing the vole at the point of capture. Nymph and adult ticks were not removed to avoid any impact on transmission of tick-borne infections which were being studied as part of an extensive longitudinal program.

The numbers of questing exophilic ticks was sampled monthly over the same period by blanket dragging. Briefly, a 3-m2 woollen blanket was dragged through the vegetation for 10 m and then checked for ticks. This was repeated 10 times at each site, yielding a total of 300 m2 of vegetation sampled per grid per month on days with no rainfall. All ticks were collected from the blanket using forceps and stored in 70% ethanol for subsequent PCR analysis.

DNA extraction and microparasite detection.

DNA was extracted from blood samples and questing ticks by alkaline digestion as previously reported (4). DNA from blood samples was diluted 1:10 in sterile molecular-grade water (Sigma, United Kingdom), while tick DNA extracts were analyzed undiluted.

Diagnosis of A. phagocytophilum infection was achieved using a previously published real-time PCR method (9) performed on a DNA engine Opticon2 real-time machine (Bio-Rad, United Kingdom). Reaction mixtures contained 3.125 pmol of probe, 22.5 pmol of each primer, 12.5 μl of 2× master mix (Abgene, Surrey, United Kingdom), and 1 μl of DNA template made up to a final volume of 25 μl with sterile molecular-grade water. B. microti infections were also diagnosed using a real-time approach. Primers and probe were designed to be specific for B. microti strains previously identified in field voles from Kielder Forest: forward primer KebabF (5′-GAATTTCTGCCTTGTCATTAATC-3′), reverse primer KebabR (5′-GTAAATACTGGAAGATAGTAAGG-3′), and the 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled probe KebabP (5′-TATTGACTTGGCATCTTCTGGATTTGGTATCC-3′). These reagents were incorporated into PCRs at the same concentrations as those for A. phagocytophilum and subjected to an initial denaturing step of 2 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s and 58°C for 50 s.

Statistical analyses.

To investigate the effect of fencing on tick abundance, general linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used with either larval burden of field voles (for both tick species, assuming a negative binomial error and log link) or questing I. ricinus abundance as the response variable. In order to maximize the power of tests of the effect of deer reduction on tick burden (a two-level fixed variable with “deer excluded” and “unfenced control”), we first corrected statistically for the likely influence of site-level and individual-level covariates on observed tick burdens. The fixed effect site-level variables were month, number of questing I. ricinus nymphs collected by dragging that month, and the proportion of hosts infested with I. ricinus and I. trianguliceps larvae that month, while the individual-level fixed effects were an animal's sex, its weight (and weight squared to account for possible nonlinearities), and the presence of nonlarval ticks. In addition, the potential significance of interactions between an individual's sex and weight were also considered. Model selection was based on backward stepwise model selection with variables dropped according to P value, with only those variables significant at the P < 0.05 level being retained in the final model (34). GLMMs were used to take account of the nonindependence of samples from a site at any given time by using “site * session” as a random effect. As the average number of recaptures for an individual field vole was only 1.6, any problem with repeated measured on individuals was likely to be trivial and the individual's identification was not included as a random effect. GLMMs (with binomial errors) were also used to investigate the significance of the same covariates when the presence of nonlarval ticks was considered as the response variable.

GLMMs were also used to determine those variables significantly associated with infection with A. phagocytophilum and B. microti assuming a binomial error term and a logit link. The population-level variables were as described above, while the additional individual-level variable of whether an animal showed signs of infection with the other infectious agent was also considered. Mixed-effect models were fitted using the function glmmPQL from the MASS library of R 2.4.1 (R Development Core Team, 2006) for the models with negative binomial errors, and the function lmer from the lme4 library for the models with binomial errors.

RESULTS

Summary of tick infestation and questing tick abundance.

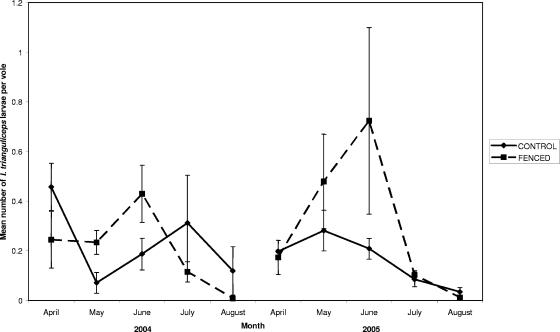

The presence of both tick species was confirmed at all eight sites. However, shortly after commencing the study, it became apparent that one of the exclosures was not effective in excluding deer (fresh feces and tracks present) so data from it are not included in the subsequent analyses. The mean infestations of larvae per vole in the fenced and control sites are shown separately for the two tick species (Fig. 1 and 2), while the numbers of I. ricinus nymphs collected by blanket dragging are shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 1.

Mean number of Ixodes ricinus larvae per vole recorded over the duration of the study on both control and fenced sampling grids. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

FIG. 2.

Mean number of I. trianguliceps larvae per vole recorded over the duration of the study on both control and fenced sampling grids. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

FIG. 3.

Number of questing nymphs collected by blanket dragging over a 300-m2 area on control and fenced sampling grids. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

GLMM analyses on factors influencing abundance of I. ricinus larvae on field voles.

The exclusion of deer had a major effect on the abundance of I. ricinus larvae infesting field voles (Table 1), with the model predicting that voles from exclosure sites would have an approximately 14-fold reduction in their larval burden compared to those voles on control grids. Larval burdens varied significantly seasonally, peaking in May, June, and July. At the individual level males carried larger numbers of ticks than females at all bodyweights greater than 10 g; furthermore, tick burden increased more rapidly with increasing body weight among male voles than females (significant interaction between I. ricinus larval burden and vole sex and weight, P < 0.01). Voles infested with a nonlarval tick (nymph or adult) carried approximately 5 times more larvae than those infested with larvae alone.

TABLE 1.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for the models of I. ricinus or I. trianguliceps larvae, nonlarval ticks, and questing I. ricinus nymphs

| Parameter | Effect on modela:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I. ricinus larvae

|

I. trianguliceps larvae

|

Mature ticks

|

Questing nymphs

|

|||||||||

| Coefficient (SE) | t value | P value | Coefficient (SE) | t value | P value | Coefficient (SE) | t value | P value | Coefficient (SE) | t value | P value | |

| Intercept | −0.057 (0.75) | −0.76 | 0.45 | 0.45 (0.39) | 1.15 | 0.25 | −3.44 (0.34) | −10.01 | <0.01 | 3.33 (0.31) | 10.79 | <0.01 |

| Male | −1.40 (0.61) | −2.30 | 0.02 | −0.26 (0.36) | −0.71 | 0.48 | 0.54 (0.13) | 4.32 | <0.01 | |||

| wt relationship | ||||||||||||

| wt | −0.20 (0.04) | −5.22 | <0.01 | −0.09 (0.01) | −6.48 | <0.01 | ||||||

| wt2 | 0.00 (0.00) | 4.46 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Male * wt | 0.14 (0.05) | 2.85 | <0.01 | 0.03 (0.02) | 2.12 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Male * wt2 | −0.00 (0.00) | −2.08 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| Larval ticks | ||||||||||||

| I. ricinus | 0.15 (0.02) | 6.67 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| I. trianguliceps | 0.25 (0.08) | 3.22 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Mature ticks | 1.36 (0.12) | 11.65 | <0.01 | 0.71 (0.16) | 4.55 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Deer excluded | −2.38 (0.39) | −6.04 | <0.01 | −2.52 (0.31) | −8.19 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Larval burden | ||||||||||||

| August | 0.61 (0.70) | 0.88 | 0.38 | −2.59 (0.42) | −6.17 | <0.01 | 1.59 (0.37) | 4.33 | <0.01 | −1.69 (0.45) | −3.75 | <0.01 |

| July | 1.80 (0.69) | 2.61 | 0.01 | −0.99 (0.36) | −2.81 | <0.01 | 1.02 (0.38) | 2.71 | <0.01 | −0.06 (0.50) | −0.12 | 0.91 |

| June | 2.25 (0.68) | 3.29 | <0.01 | −0.18 (0.34) | −0.53 | 0.60 | 1.57 (0.37) | 4.21 | <0.01 | −0.55 (0.42) | −1.32 | 0.19 |

| May | 1.73 (0.69) | 2.48 | 0.02 | −0.22 (0.35) | −0.63 | 0.53 | 1.02 (0.38) | 3.15 | <0.01 | 0.31 (0.41) | 0.31 | 0.76 |

The values shown are log scale for I. ricinus and I. trianguliceps larvae and I. ricinus nymphs and logit scale for nonlarval (mature) ticks. Probabilities that are significant at the P < 0.05 level are in boldface.

GLMM analyses of factors associated with Ixodes trianguliceps larval burdens.

In contrast to I. ricinus, deer reduction was not significantly associated with rodent infestation with I. trianguliceps larvae (Table 1). As with I. ricinus, burden varied with season, with larval numbers peaking between April and June. Again, there was an interaction at the individual level between tick burden and vole sex and body weight due to the fact that males of all but the lightest body weights hosted higher numbers of larvae than females. However, in contrast to I. ricinus, the burden of I. trianguliceps larvae decreased with increased body weight for both sexes, with this decrease occurring more rapidly for females. Again, the infestation with a nonlarval tick was positively associated with increased larval burden, this time of a magnitude of 2.3-fold.

Nonlarval tick abundance.

Markedly fewer nymph or adult ticks than larvae were observed on rodents, with the vast majority of infested animals hosting just a single tick (although up to 12 nymphs and 9 adults were observed on individuals). There was no significant difference in the abundance of nonlarval ticks on voles at exclosure or control sites, but the sampling month was important, with significantly fewer animals infested with nonlarval ticks in April (Table 1). Male voles were 1.5 times more likely to be infested with nymphal or adult ticks than female voles, and those voles infested with larvae of either tick species were more likely to have a nymphal or adult tick feeding upon them than voles not infested with larvae.

Questing nymph abundance.

The abundance of questing I. ricinus nymphs was reduced by a factor of approximately 12.5 times at exclosure sites than at control sites (Table 1). The highest mean numbers of questing nymphs were collected between April and July. No significant difference between the prevalence of A. phagocytophilum infection in questing nymphs at exclosure and control sites was observed; however, only very few infected ticks were encountered (7 of 1,033 tested). We were unable to detect B. microti DNA in any questing I. ricinus ticks.

Summary of rodent sampling and infection.

Over the course of the study, a total of 2,402 blood samples were collected from 1,516 individual field voles: 1,216 samples (50.6%) were from females and 1,186 (49.4%) were from males. Of these samples, A. phagocytophilum DNA was detected in 165 (6.7%) and B. microti DNA was detected in 671 (27.2%). DNA from both hemoparasites was detected in 80 samples (3.3%). The seasonal variation in infection prevalence of the two infections for the exclosure and control sites is shown in Fig. 4 and 5. Examination of PCR results from repeatedly sampled animals indicated that A. phagocytophilum infections were largely short-lived, being detected in an individual on just one occasion, whereas B. microti infections were chronic, with an individual, once infected, remaining infected in all subsequent samples.

FIG. 4.

Infection prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in field voles sampled on both control and fenced grids. Error bars represent exact binomial 95% confidence intervals.

FIG. 5.

Infection prevalence of Babesia microti in field voles sampled on control and fenced grids. Error bars represent exact binomial 95% confidence intervals.

GLMM analyses. (i) A. phagocytophilum.

The prevalences of A. phagocytophilum infections did not differ significantly between vole populations inhabiting exclosure sites and those inhabiting control sites (Table 2). Animals infected with B. microti were approximately 2.6 times more likely to also be infected with A. phagocytophilum, while we also found a correlation between tick infestation and infection status, with animals infested with a nymphal or adult tick being 1.4 times more likely to be infected with A. phagocytophilum.

TABLE 2.

Parameter estimates and standard errors for the models of Anaplasma and Babesia infections in field voles (Microtus agrestis)

| Parameter | Effect on volesa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anaplasma positive

|

Babesia positive

|

|||||

| Coefficient (SE) | z value | Probability > z | Coefficient (SE) | z value | Probability > z | |

| Intercept | −3.25 (0.14) | −23.44 | <0.01 | −3.92 (0.44) | −8.95 | <0.01 |

| Infection | ||||||

| Babesia positive | 1.07 (0.17) | 6.21 | <0.01 | |||

| Anaplasma positive | 1.03 (0.18) | 5.81 | <0.01 | |||

| Nonlarval ticks | 0.43 (0.21) | 2.04 | 0.04 | 0.41 (0.14) | 2.99 | <0.01 |

| wt relationship | ||||||

| wt | 0.16 (0.03) | 5.79 | <0.01 | |||

| wt2 | −0.00 (0.00) | −3.63 | <0.01 | |||

| Larval burden | ||||||

| August | −0.16 (0.20) | −0.77 | 0.44 | |||

| July | −0.19 (0.21) | −0.91 | 0.36 | |||

| June | −0.53 (0.21) | −2.50 | 0.01 | |||

| May | −0.56 (0.22) | −2.56 | 0.01 | |||

The values shown are in logit scale. Probabilities that are significant at the P < 0.05 level are in boldface.

(ii) B. microti.

The prevalence of B. microti infections did not differ significantly between vole populations inhabiting exclosure or control sites (Table 2). As observed for A. phagocytophilum, those individuals infected with one hemoparasite were more likely to be infected with the other. For example, the probability of B. microti infection was 1.6 times higher for a 30-g vole infected with A. phagocytophilum than for a noninfected vole. The relationship between body mass and infection status was nonlinear, with an increasing probability of infection with increased body mass up to approximately 50 g, after which the probability of infection falls. Once again, those individuals infested with nonlarval ticks were more likely to test positive (1.3 times for the 30-g vole). Seasonality also had a significant effect on the probability of testing positive, with those sampled in May and June being less likely to be positive than those from April, although this may be primarily driven by the very high prevalence seen in April 2004 at the fenced sites (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

We investigated the roles of two tick species, Ixodes ricinus and I. trianguliceps in the transmission of tick-borne hemoparasites within populations of field voles by utilizing fencing used to manipulate distribution of roe deer, a key host for adult I. ricinus. As predicted, the use of this fencing to exclude deer from an area significantly reduced the abundance of I. ricinus. Numbers of questing I. ricinus ticks were reduced approximately 12-fold at those sites where deer were absent, while mean larval burdens on field voles at these sites were also reduced by a similar amount. These data are in line with previous studies in which reductions in the abundance of I. ricinus or Ixodes scapularis were observed following either the removal of deer or a reduction in their numbers (2, 3, 10, 25).

In contrast to the significant effect that deer reduction had on I. ricinus abundance, there was, as we hypothesized, no evidence of a similar effect on I. trianguliceps abundance. These observations are consistent with the reliance of I. ricinus on large mammals as hosts for adult females ticks (21), while all three developmental stages of I. trianguliceps feed on small mammals (8, 26), the abundances of which were similar at the exclosure and control sites.

While there was a significant effect of deer reduction on I. ricinus abundance, infection prevalence in field voles was not significantly affected. This discovery that I. ricinus abundance was not significantly associated with the prevalence of tick-borne infections in field voles is consistent with this species not playing an important role in the transmission of A. phagocytophilum or B. microti between field voles. The consequence of this is that another vector must fulfill this role and given that I. trianguliceps was the only other tick species encountered at our sites, it is highly probable that it is this species that does so. This conclusion is in keeping with our previous finding that A. phagocytophilum can be maintained in woodland rodent communities, a region of the United Kingdom where I. trianguliceps is present but I. ricinus is not (4). Support for the importance of I. trianguliceps in the natural maintenance of tick-borne parasites in rodent communities in the United Kingdom is also drawn from a study by Ogden and colleagues (22), who failed to find evidence of A. phagocytophilum infection in rodent populations inhabiting sites where I. ricinus was present but I. trianguliceps was not. Interestingly, evidence exists that in continental Europe I. ricinus is an important vector of rodent A. phagocytophilum infections (20), as it is of other tick-borne infections with rodent reservoirs such as members of the Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. group and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEv) (17, 18). This suggests that marked differences in the transmission cycle of A. phagocytophilum may exist. Previous work has suggested that rodents in the United Kingdom generally have lower levels of infestation with I. ricinus nymphs than their continental counterparts, possibly as a consequence of differences in climatic conditions (30).

Our observation that deer abundance was not significantly associated with the proportion of field voles infested with nymphal or adult (and therefore potentially infected) ticks suggests that most of these were I. trianguliceps, especially as adult I. ricinus ticks are virtually never found on rodents. As A. phagocytophilum prevalence in questing I. ricinus nymphs was very low (∼1%), the nondependence of A. phagocytophilum transmission to rodents by this species may simply be a result of insufficient numbers feeding upon these hosts.

Our findings that none of the questing I. ricinus nymphs or adults tested positive for B. microti DNA and that deer abundance (and consequently I. ricinus abundance) was not significantly associated with rodent infection are in agreement with previous studies that proposed that I. trianguliceps is the principal vector of B. microti in rodents in the United Kingdom (29, 36). Although there is evidence from other studies that I. ricinus may be a competent vector of B. microti (12, 15), the strain of B. microti investigated in these studies was from continental Europe and may differ in its host/vector specificity from that present in the United Kingdom.

In addition to identifying I. trianguliceps as the principal vector of these infections, this study highlights both similarities and differences in the host-tick relationship for the two tick species. For all but the lightest voles, males carried a higher larval burden of both species and were more likely to be infested with nymphal and adult ticks than females, although interestingly sex differences were not associated with increased probability of infection. Male rodents have previously been reported to have greater tick burdens (23, 27), and this is considered to be a result of the higher levels of testosterone in male voles reducing their resistance to tick infestations (16) and/or the greater home range they occupy (14) increasing their exposure to ticks. However, the relationship between larval burden and host body mass for the two tick species differed: while, in general, the host burden of I. ricinus larvae increased with increasing body mass, the reverse was true for I. trianguliceps. This may result from the different questing behaviors of the tick species, with I. ricinus being exophilic (actively quests above ground) and I. trianguliceps endophilic/nidicolous (nest dwelling). As such, immature voles spending a greater time in the proximity of the nest would have greater exposure to I. trianguliceps, while mature animals, particularly males which have the greatest home range (14), have increased potential for coming into contact with questing I. ricinus larvae. Another possibility is that the voles are showing resistance to I. trianguliceps infestation but not I. ricinus, but previous studies have shown that bank voles acquire immunity to infestation with both tick species (11, 28).

While the results of this study question the relative importance of I. ricinus as a vector of rodent-associated tick-borne infections in United Kingdom uplands, they do provide further evidence that the potential exists for infections maintained in an enzootic rodent—for the I. trianguliceps system to escape, via I. ricinus, into other hosts. Both tick species were found on rodents at each of the eight sites studied, and although rodents appear to be relatively unimportant as hosts to nymphal and adult I. ricinus ticks, larval infestations of rodents were common and, at those sites where deer movement was unrestricted, the tick numbers were higher than those of I. trianguliceps. As such, the potential exists for large numbers of I. ricinus ticks to acquire infected blood meals from rodents and pass the pathogens on when they feed as nymphs on other host species.

Further work is still required to fully determine the importance of rodents in the epidemiology of tick-borne infections in the United Kingdom. We are currently assessing the relative importance of rodents, in comparison to deer and other potential hosts, as hosts to larval I. ricinus to determine the potential contribution of rodents to infecting I. ricinus larvae. It would also be interesting to conduct more studies in areas where only I. ricinus is present to establish whether rodent infections can be maintained in the absence of I. trianguliceps.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant no. 070675/Z/03/Z).

We are grateful to the Forestry Commission for allowing us access to their land and Roz Anderson, Jenny Rogers, Pablo Beldomenico, and Lukasz Lukomski for assisting with the fieldwork.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur, D. R. 1963. British ticks. Butterworths, London, United Kingdom.

- 2.Bloemer, S. R., E. L. Snoddy, J. C. Cooney, and K. Fairbanks. 1986. Influence of deer exclusion on populations of lone star ticks and American dog ticks (Acari, Ixodidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 79:679-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloemer, S. R., G. A. Mount, T. A. Morris, R. H. Zimmerman, D. R. Barnard, and E. L. Snoddy. 1990. Management of lone star ticks (Acari, Ixodidae) in recreational areas with acaricide applications, vegetative management and exclusion of white-tailed deer. J. Med. Entomol. 27:543-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bown, K. J., M. Begon, M. Bennett, Z. Woldehiwet, and N. H. Ogden. 2003. Seasonal dynamics of Anaplasma phagocytophila in a rodent-tick (Ixodes trianguliceps) system, United Kingdom. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:63-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bown, K. J., M. Begon, M. Bennett, R. J. Birtles, S. Burthe, X. Lambin, S. Telfer, Z. Woldehiwet, and N. H. Ogden. 2006. Sympatric Ixodes trianguliceps and Ixodes ricinus ticks feeding on field voles (Microtus agrestis): potential for increased risk of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in the United Kingdom? Vector Borne Zoonot. Dis. 6:404-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, R. N., and R. S. Lane. 1992. Lyme disease in California: a novel enzootic transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Science 256:1439-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, S.-M., J. S. Dumler, J. S. Bakken, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotton, M. J., and C. H. S. Watts. 1967. The ecology of the tick Ixodes trianguliceps Birula (Arachnida; Acarina; Ixodoidea). Parasitology 57:525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courtney, J. W., L. M. Kostelnik, N. S. Zeidner, and R. F. Massung. 2004. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3164-3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deblinger, R. D., M. L. Wilson, D. W. Rimmer, and A. Spielman. 1993. Reduced abundance of immature Ixodes dammini (Acari, Ixodidae) following incremental removal of deer. J. Med. Entomol. 30:144-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dizij, A., and K. Kurtenbach. 1995. Clethrionomys glareolus, but not Apodemus flavicollis, acquires resistance to lxodes ricinus L, the main European vector of Borrelia burgdorferi. Parasite Immunol. 17:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duh, D., M. Petrovec, and T. Avsic-Zupanc. 2001. Diversity of Babesia infecting European sheep ticks (Ixodes ricinus). J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3395-3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gern, L., and A. Aeschlimann. 1986. Etude seroepidemiologique de 2 foyers a babesie de micromammiferes en Suisse. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 128:587-600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gipps, J. H. W., and S. K. Alibhai. 1991. Field vole, p. 203-208. In G. B. Corbett and S. Harris (ed.), The handbook of British mammals, 3rd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 15.Gray, J., L. V. von Stedingk, M. Gürtelschmid, and M. Granström. 2002. Transmission studies of Babesia microti in Ixodes ricinus ticks and gerbils. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1259-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes, V. L., and S. E. Randolph. 2001. Testosterone depresses innate and acquired resistance to ticks in natural rodent hosts: a force for aggregated distributions of parasites. J. Parasitol. 87:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humair, P. F., O. Rais, and L. Gern. 1999. Transmission of Borrelia afzelii from Apodemus mice and Clethrionomys voles to Ixodes ricinus ticks: differential transmission pattern and overwintering maintenance. Parasitology 118:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labuda, M., O. Kozuch, E. Zuffova, E. Eleckova, R. S. Hails, and P. A. Nuttall. 1997. Tick-borne encephalitis virus transmission between ticks co-feeding on specific immune natural rodent hosts. Virology 235:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambin, X., S. J. Petty, and J. L. MacKinnon. 2000. Cyclic dynamics in field vole populations and generalist predation. J. Anim. Ecol. 69:106-118. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liz, J. S., L. Anderes, J. W. Sumner, R. F. Massung, L. Gern, B. Rutti, and M. Brossard. 2000. PCR detection of granulocytic ehrlichiae in Ixodes ricinus ticks and wild small mammals in western Switzerland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1002-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milne, A. 1949. The ecology of the sheep tick, Ixodes ricinus L—host relationships of the tick. 2. Observations on hill and moorland grazings in northern England. Parasitology 39:173-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogden, N. H., K. Bown, B. K. Horrocks, Z. Woldehiwet, and M. Bennett. 1998. Granulocytic Ehrlichia infection in ixodid ticks and mammals in woodlands and uplands of the UK. Med. Vet. Entomol. 12:423-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins, S. E., I. M. Cattadori, V. Tagliapietra, A. P. Rizzoli, and P. J. Hudson. 2003. Empirical evidence for key hosts in persistence of a tick-borne disease. Int. J. Parasitol. 33:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petty, S. J. 1999. Diet of tawny owls (Strix aluco) in relation to field vole (Microtus agrestis) abundance in a conifer forest in northern England. J. Zool. (London) 248:451-465. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rand, P. W., C. Lubelczyk, M. S. Holman, E. H. Lacombe, and R. P. Smith. 2004. Abundance of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) after the complete removal of deer from an isolated offshore island, endemic for Lyme disease. J. Med. Entomol. 41:779-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randolph, S. E. 1975. Seasonal dynamics of a host-parasite system: Ixodes trianguliceps (Acarina: Ixodidae) and its small mammal hosts. J. Anim. Ecol. 44:425-449. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randolph, S. E. 1975. Patterns of distribution of the tick Ixodes trianguliceps Birula on its hosts. J. Anim. Ecol. 44:451-474. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randolph, S. E. 1994. Density-dependent acquired resistance to ticks in natural hosts, independent of concurrent infection with Babesia microti. Parasitology 108:413-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randolph, S. E. 1995. Quantifying parameters in the transmission of Babesia microti by the tick Ixodes trianguliceps amongst voles (Clethrionomys glareolus). Parasitology 110:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Randolph, S. E., and K. Storey. 1999. Impact of microclimate on immature tick-rodent host interactions (Acari: Ixodidae): implications for parasite transmission. J. Med. Entomol. 36:741-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snow, K. R. 1979. Identification of larval ticks found on small mammals in Britain. The Mammal Society, Reading, United Kingdom.

- 32.Spielman, A. 1988. Lyme disease and human babesiosis: evidence incriminating vector and reservoir hosts, p. 147-165. In P. T. Englund and A. Sher (ed.), The biology of parasitism. A molecular and immunological approach. Alan R. Liss, New York, NY.

- 33.Telford, S. R., J. E. Dawson, P. Katavlos, C. K. Warner, C. P. Kolbert, and D. H. Persing. 1996. Perpetuation of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a deer tick-rodent cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6209-6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venables, W. N., and B. D. Ripley. 2002. Modern applied statistics with S. Springer, London, United Kingdom.

- 35.Woldehiwet, Z., and G. R. Scott. 1993. Tick-borne (Pasture) fever, p. 233-254. In Z. Woldehiwet and M. Ristic (ed.), Rickettsial and chlamydial diseases of domestic animals. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 36.Young, A. S. 1970. Studies on the blood parasites of small mammals with special reference to piroplasms. Ph.D. dissertation. University of London, London, United Kingdom.