Abstract

Isoflavone glucosides are valuable nutraceutical compounds and are present in commercial fermentations, such as the erythromycin fermentation, as constituents of the soy flour in the growth medium. The purpose of this study was to develop a method for recovery of the isoflavone glucosides as value-added coproducts at the end of either Saccharopolyspora erythraea or Aeromicrobium erythreum fermentation. Because the first step in isoflavone metabolism was known to be the conversion of isoflavone glucosides to aglycones by a β-glucosidase, we chose to knock out the only β-glucosidase gene known at the start of the study, eryBI, to see what effect this had on metabolism of isoflavone glucosides in each organism. In the unicellular erythromycin producer A. erythreum, knockout of eryBI was sufficient to block the conversion of isoflavone glucosides to aglycones. In S. erythraea, knockout of eryBI had no effect on this reaction, suggesting that other β-glucosidases are present. Erythromycin production was not significantly affected in either strain as a result of the eryBI knockout. This study showed that isoflavone metabolism could be blocked in A. erythreum by eryBI knockout but that eryBI knockout was not sufficient to block isoflavone metabolism in S. erythraea.

Many industrial fermentations use soy flour as a growth medium component. Recovery of the isoflavones from this soy flour represents an untapped source of value-added fermentation coproducts. For over 10 years, the isoflavones genistein and daidzein have been intensively investigated to determine their health benefits (1, 7, 9) and have been added as nutraceutical ingredients to food and health products. Erythromycin fermentation was the first pharmaceutical fermentation to be investigated as a model system for isoflavone recovery (5). Erythromycin is a bulk fermentation product used in its natural form and in various salt forms as an antibiotic. It is also used as a chemical intermediate in the production of other widely prescribed antibiotics, including azithromycin, clarithromycin, dirithromycin, and roxithromycin. Hundreds of thousands of tons of erythromycin are produced each year. The amount of isoflavone coproduced could be as much as 0.5 to 1% of the amount of erythromycin produced, and since the value of isoflavones per unit of weight is as much as 10 times the value of erythromycin, a significant economic gain could be obtained. In a previous study (5), it was found that the main technical problem with recovering isoflavones as coproducts was their bioconversion and degradation by the fermentation organism. Therefore, in order to make isoflavone recovery technically possible, a method for blocking isoflavone metabolism was sought.

Previously, we reported that in the course of erythromycin fermentation, Saccharopolyspora erythraea enzymatically hydrolyzes glucose from the isoflavone glucosides genistin and daidzin. However, the β-glucosidase used in this biotransformation was not identified or characterized (5). Interestingly, the erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster, which has been extensively studied and characterized in S. erythraea (for a review, see reference 12), contains a β-glucosidase gene. This gene was referred to originally as eryBI (18) and later was renamed orf2 because of its lack of involvement in erythromycin biosynthesis in S. erythraea (4); more recently, it has been suggested that the designation should be changed to eryB1 (12).

eryBI was originally defined as a genetic locus immediately downstream of the ermE gene in S. erythraea. Its map location corresponded to the insertion site of pMW55-27 via the cloned DNA fragment BI-27 (Fig. 1) (18). Insertion of pMW55-27 into the chromosome resulted in a block in erythromycin A production and accumulation of the erythromycin precursor erythronolide B, giving the mutant the EryB phenotype (17). The eryBI-27 mutation, however, was created and analyzed before the DNA sequence of this region was available. Later, after the sequence was published (4), it was seen that pMW55-27 inserted close to, or possibly overlapped, the 3′ terminus of the open reading frame in this region. Why plasmid pMW55-27 conferred the EryB phenotype after insertion into this region of eryBI is unknown. It would have been expected to simply confer a wild-type phenotype, like other mutations in this gene (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, because of this result, the gene downstream of ermE became known as eryBI despite its lack of involvement in erythromycin biosynthesis under the conditions tested so far.

FIG. 1.

Structure of erythromycin A and map of the eryBI region of the S. erythraea erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster. The scale for the map positions is based on the convention used for the genomic sequence (8). Restriction sites were mapped using the genomic sequence information; however, the restriction site numbering system is that of Weber et al. (18). The pFL2191-D and pFL2191-U lines represent PCR fragments generated during construction of plasmid pFL2191 used for deletion of eryBI in S. erythraea. The abbreviations for the restriction sites at the PCR product ends are as follows: S, SstI; E, EcoRI; and H, HindIII. The pFL2168 line represents the equivalent homologous A. erythreum DNA fragment generated by PCR from an A. erythreum DNA template and cloned to create pFL2168 for knockout of the eryBI gene of A. erythreum. Double asterisks indicate the eryBI mutations described by Gaisser et al. (4); single asterisks indicate the mutations described by Weber et al. (18). The colored boxes indicate the putative conserved domains detected by BLASTP analysis of the EryBI amino acid sequence (September 2008). The numbers above the domain structure refer to the amino acid sequence of the EryBI protein of S. erythraea. The gray box indicates the equivalent OH group in oleandomycin that is glucosylated by the oleandomycin glucosyltransferase and then hydrolyzed by OleR, both of which are components of the oleandomycin resistance mechanism of S. antibioticus (11).

A new theory about a possible function for EryBI was proposed when EryBI was found to be homologous to OleR (61% identity to the OleR amino acid sequence) encoded by a gene in the oleandomycin gene cluster. OleR functions as a component of the oleandomycin self-resistance mechanism in Streptomyces antibioticus (11). Its β-glucosidase activity is specific to the oleandomycin glucoside made by S. antibioticus. It was hypothesized that at one time, EryBI may have played a role analogous to that of OleR in S. erythraea. However, unlike oleR, the eryBI gene was thought to have become nonfunctional because it was redundant after S. erythraea acquired a second, more effective erythromycin resistance gene, ermE (11). The experimental data at the time were consistent with this theory and with the conclusion that eryBI is a nonfunctional gene.

When this study began, there was no evidence of linkage between eryBI and isoflavone metabolism, although the possibility of a connection had been discussed (4). To address this possibility, experiments were performed using two different erythromycin-producing organisms, S. erythraea and Aeromicrobium erythreum (2), in order to test for β-glucosidase activity against isoflavone glucosides. The hypothesis was that if the eryBI gene was found to be involved in the conversion of isoflavone glucosides, then inactivation of eryBI could make the recovery of isoflavone glucoside coproducts from erythromycin fermentation possible without interfering with erythromycin production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The general materials and methods used for Escherichia coli and Actinomycetes were described by Sambrook et al. (16) and Kieser et al. (6), respectively. The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. We used S. erythraea FL2267, a “white” strain and a derivative of ATCC 11635 (15); also, we used A. erythreum wild-type strain FL262 (= NRRL B-3381), which has been described previously (14). We also used S. erythraea strain FL1347, a red variant strain which is a spontaneous, red-pigmented derivative of S. erythraea white strain ATCC 11635 and produces small amounts of erythromycin. FL1347 transforms with plasmid DNA at a higher efficiency than FL2267. Spores of S. erythraea white strains were produced on E20A agar (13). A. erythreum was maintained on 2× YT agar plates or as glycerol stocks at −80°C. OFM1 (which contains 22 g/liter soy flour) and CFM1 medium have been described previously (15); modified SCM (MSCM) fermentation broth has also been described previously (14). When fermentations were performed in MSCM supplemented with soy flour, 22 g/liter of soy flour was added.

TABLE 1.

S. erythraea and A. erythreum strains and plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Plasmid insert or strain description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pFL8 | S. erythraea parent plasmid used for generation of integration vectors; carries genes for ampicillin and thiostrepton resistance | 13 |

| pFL2092 | A. erythreum vector used for integrating DNA sequences via homologous recombination; contains the thiostrepton resistance gene from pIJ487 cloned into the EcoRI and KpnI sites of pFL2082; carries genes for ampicillin, kanamycin, and thiostrepton resistance | 14 |

| pFL2168 | A. erythreum integration vector containing a 593-bp eryBI internal fragment cloned into the unique EcoRI site of pFL2092; used to generate a knockout in eryBI by single-crossover insertion; carries genes for ampicillin, kanamycin, and thiostrepton resistance | This study |

| pFL2191 | S. erythraea gene replacement vector used to delete eryBI and insert aphI (kanamycin resistance gene) in its place | 15 |

| Strains | ||

| FL1347 | Red variant (less erythromycin produced) derivative of S. erythraea ATCC 11635 | 13 |

| FL2296 | Derivative of S. erythraea FL1347 with eryBI deleted and replaced by the aphI (kanamycin resistance) gene using pFL2191 | This study |

| FL2267 | White derivative of S. erythraea ATCC 11635; wild-type white strain; used as host strain for transformation | 15 |

| FL2316 | Derivative of S. erythraea FL2267 with the eryBI gene deleted and replaced by the aphI (kanamycin resistance) gene using pFL2191 | This study |

| FL262 | Wild-type A. erythreum strain; NRRL-B-3381 | 14 |

| FL2264 | Derivative of A. erythreum FL262 having a knockout in eryBI due to single-crossover insertion of pFL2168 | This study |

| E. coli DH5α-e | Host strain used for electroporation | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA |

Plasmids used to create eryBI knockouts in A. erythreum and S. erythraea.

Plasmid pFL2168, which was used to create the eryBI knockout in A. erythreum, was constructed from an internal 593-bp eryBI PCR fragment (Fig. 1) cloned into pFL2092 (14). The A. erythreum chromosomal DNA template was used with primers eryBIAeF1 (5′-GTCGGATCCGCTGCAGATCATGCTCTCCG-3′) and eryBIAeR1 (5′-GTCGGATCCACACGTCGGTGACGCGCATC-3′). The PCR product was ligated into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI) and then electroporated into E. coli DH5α-e and plated on 2× YT agar (16) containing ampicillin and the indicator X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). Plasmids were isolated from colorless transformants and analyzed by using restriction analysis, and the DNA sequence of the insert was determined to confirm its identity. The resulting intermediate construct, pFL2164, was digested with EcoRI to release the eryBI fragment, which was ligated to EcoRI-digested pFL2092. Ligation mixtures were electroporated into E. coli DH5α-e, and recombinant plasmids were confirmed by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing. One plasmid, pFL2168-1, was used to transform wild-type A. erythreum using the method of Reeves et al. (14).

Plasmid pFL2191, which was used for generation of S. erythraea eryBI deletion strain FL2316, was constructed by using four components. The first component was pFL8 (13) digested with SacI and HindIII. The second and third components were obtained from PCR products amplified from two noncontiguous chromosomal regions (pFL2191-D, downstream of eryBI; and pFL2191-U, upstream of eryBI [Fig. 1]). The primers used to generate a PCR product downstream of eryBI in pFL2191-D were CISEFD-1 (5′-GTCGAGCTCCCGTCGCCCAGCGCTCCGAG) and ermERV-1 (5′-GTCGAATTCGCCTGCCCCGTTCCGCGTGC). The primers used to generate a PCR product upstream of eryBI were BIPROFD-1 (5′-GTCGAATTCAGTCGTAAACCGGCTGATGT) and FSERV-1 (5′-GTCAAGCTTGAGCAGCTCGCAGATGACCT). The fourth component used for ligation was the kanamycin resistance gene from pUC4K (Pharmacia Biochemicals, Piscataway, NJ), which was released by digestion with EcoRI. The four components were ligated together and electroporated into E. coli cells with selection for kanamycin-resistant clones on 2× YT plates. One plasmid, pFL2191-1 (Table 1), was used to transform S. erythraea FL2267 (white) and FL1347 (red) protoplasts as described by Reeves et al. (15) with selection for Knr transformants.

Confirmation of gene knockouts in eryBI mutants by PCR.

PCR primers were designed so that a 1.879-kb region was amplified in A. erythreum eryBI mutant FL2264 but was missing in wild-type strain FL262. Based on the predicted integration of pFL2168, the region amplified 278 bp of ermA (2), 1.513 kb of the adjacent region in eryBI, and 88 bp of pFL2092. The primers used were forward primer ermAeF1 (5′-CTCGAAGGTCGACAGCGCGT-3′) and reverse primer 2092B1R1 (5′-AGCTGGCGAAAGGGGGATGT-3′). The reverse primer was located 88 bp upstream of the EcoRI site of pUC19-based (pFL2092) plasmids.

To confirm that there was gene replacement in pFL2191 and that there was insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene in S. erythraea FL2316, PCR primers were designed to amplify a 1.549-kb region spanning the inserted kanamycin resistance gene and surrounding upstream (ermE) and downstream (eryBIII) sequences. The primers used were forward primer ermEF1 (5′-GACGCAATCGCGACGACGGA-3′) and reverse primer eryBIIISeR1 (5′-CGCATATGCGGCATTTGCCT-3′).

Shake flask fermentations.

For A. erythreum seed preparation, 25 ml of MSCM in 250-ml flasks was inoculated with 250 μl of a frozen glycerol stock culture and incubated at 380 circular rpm, 65% relative humidity, and 32.5°C for 24 h. For FL2264, a thiostrepton-resistant eryBI mutant strain, thiostrepton was added to MSCM at a concentration of 3 μg/ml. Twenty-five milliliters of MSCM per 250-ml shake flask was used for fermentations. A 1.25-ml portion of an appropriate seed culture was used to inoculate a fermentation flask, and fermentation was performed under the same growth conditions that were used for the seed cultures. Broth samples (0.75 ml) were taken at intervals and stored at −80°C for later analysis.

S. erythraea shake flask fermentation was performed at 380 circular rpm in unbaffled 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks with milk filter closures. The flasks were incubated at 32.5°C and 65% humidity on an Infors Multitron shaker having a 1-in. circular displacement. Seed cultures were inoculated using fresh spores prepared from E20A agar plates; the 250-ml shake flasks each contained 25 ml of CFM1 broth (15) and were incubated on the same shaker and under the same growth conditions that were used for the fermentations. Fermentation preparations were inoculated with 1.25 ml of a seed culture in late logarithmic growth phase (40 to 45 h) and contained 25 ml of OFM1 broth. The fermentation cultures were grown for 5 days, and the final volumes were corrected for evaporation by addition of water before the cultures were analyzed further.

Processing of fermentation samples for bioassays, TLC, and HPLC.

Cells were removed from broth samples by centrifugation, and each supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm filter. A 50-μl portion of the filtered supernatant was removed for bioassay analysis, and the remainder of the supernatant was used for further analysis by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The remaining supernatant (700 μl) was extracted with 500 μl of ethyl acetate. The extract was concentrated to dryness, and the extract was then resuspended in 100 μl of acetonitrile. A 50-μl portion of the acetonitrile solution was used for HPLC analysis, 5 μl was used for analysis of isoflavones by TLC, and 10 μl was used for analysis of erythromycin by TLC.

Bioassay.

Bioassays were performed to determine the erythromycin yields in culture broth, and the methods used have been described previously (14).

TLC.

For analysis of isoflavones, 5-μl portions of the acetonitrile extracts along with standards (daidzin, genistin, and daidzein plus genistein) were applied to TLC plates, and the plates were developed using chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (10:1:1). Spots were visualized by fluorescence quenching at 254 nm. The plates were photographed while they were being exposed to the UV light. For analysis of erythromycin, 10-μl portions of the acetonitrile extracts along with 4 μl of erythromycin standards were applied to TLC plates, and the plates were developed using isopropyl ether-methanol-ammonium hydroxide (75:35:1). Spots were visualized by spraying the plates with a mixture of p-anisaldehyde, sulfuric acid, and ethanol (3:3:27) and then heating the freshly sprayed plates at 100°C for 5 min.

HPLC analysis.

The analysis of isoflavones by HPLC was performed using an Hitachi Elite LaChrom system composed of a quaternary pump, an autosampler, a UV detector, and LaChrom software. The column used was an Alltech Prevacil C18 column (5 μm; length, 250 mm; inside diameter, 4.6 mm) at 30°C. UV detection was performed at 265 nm. The injection volume was 50 μl. The mobile phase was composed of solvent A (water, 1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile, 1% formic acid), and a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min was used. Sample elution was performed by using a 25 to 50% solvent B gradient over 20 min. Linearity in the range from 0.1 to 5 μg/ml for all standards in ethanol was established, and a standard curve was used to calculate the concentrations for fermentation samples based on the peak areas.

Chemicals, biochemicals, and reagents.

Daidzin and genistin standards were obtained from LC Labs (Woburn, MA). Daidzein, genistein, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, and naringenin-7-O-glucoside were obtained from Indofine Chemical Company (Hillsborough, NJ). For A. erythreum fermentations involving spiking of pure flavonoid glucosides the compounds were added to MSCM at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml.

RESULTS

In A. erythreum, eryBI knockout blocks conversion of isoflavone glucosides.

The eryBI gene of A. erythreum was knocked out by single-crossover insertion of plasmid pFL2168 (Fig. 1) to create strain FL2264. The levels of isoflavone glucosides and aglycones were determined by HPLC over the course of 3 days of fermentation in MSCM containing soy flour, and the values obtained for parent strain FL262 and eryBI knockout strain FL2264 were compared.

Soon after inoculation, parent strain FL262 showed conversion of the isoflavone glucosides genistin and daidzin (Fig. 2A). The concentration of isoflavone glucosides dropped from 25 μg/ml at zero time to undetectable levels by 24 h. Over the same 24-h time period the concentration of the isoflavone aglycones genistein and daidzein in the medium increased from 2 μg/ml to 20 to 25 μg/ml. Once formed, the isoflavone aglycones were maintained stably for the remainder of the fermentation, and no other isoflavone biotransformation products were produced.

FIG. 2.

Isoflavone glucoside conversion by A. erythreum and S. erythraea during erythromycin fermentation in media containing soy flour. (A) A. erythreum wild-type strain FL262 (A.e. wt). (B) A. erythreum eryBI mutant FL2264 (A.e. eryBI). (C) S. erythraea wild-type strain FL2267 (S.e. wt). (D) S. erythraea eryBI mutant FL2316 (S.e. eryBI). The value for each time point is the average concentration for triplicate shake flasks determined by HPLC analysis. (E) TLC analysis of isoflavone conversion by A. erythreum in MSCM fermentations containing soy flour. Lane 1, authentic genistein reference standard; lanes 2 and 3, uninoculated MSCM containing soy flour; lanes 4 and 5, duplicate shake flask fermentations containing A. erythreum wild-type strain FL262; lanes 6 and 7, duplicate shake flask fermentations containing A. erythreum eryBI mutant FL2264. Broth samples were extracted with ethyl acetate and concentrated. Samples were loaded onto a silica gel plate and developed using chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (10:1:1), and then the plates were visualized using UV illumination.

By contrast, in A. erythreum strain FL2264 carrying the eryBI knockout mutation, the isoflavone glucoside concentrations did not drop as they did in the parent strain; instead, they were stably maintained in the fermentation broth in the range from 20 to 25 μg/ml (Fig. 2B). No other isoflavone biotransformation products appeared to form during the eryBI knockout strain fermentation, as visualized by TLC analysis (Fig. 2E).

In S. erythraea, eryBI knockout did not block conversion of isoflavone glucosides.

An eryBI knockout strain of S. erythraea FL2267 was constructed by double-crossover replacement of the eryBI gene with the kanamycin resistance gene using plasmid pFL2191 (Fig. 1) to create strain FL2316. This effectively deleted the entire eryBI gene and replaced it with the kanamycin resistance gene. This eryBI knockout strain was compared directly to parent strain FL2267 using soy flour-based shake flask fermentations with OFM1 (soy) medium.

After inoculation of parent strain FL2267 into the soy-based (OFM1) medium, the concentration of isoflavone glucosides decreased rapidly from 18 μg/ml at the first measurement to less than 5 μg/ml within the first 4 h (Fig. 2C). The rate of bioconversion was significantly higher than the rate in A. erythreum fermentations. During the initial 4-h time period the concentration of isoflavone aglycones increased from 2 μg/ml to 8 to 10 μg/ml. This level was lower than the levels of aglycones reached during the A. erythreum fermentation and was probably a reflection of how rapidly the aglycones were biotransformed further during the fermentation. When strain FL2316 carrying the eryBI knockout mutation was observed under identical conditions, the course of isoflavone metabolism was not noticeably different from the course that was observed with the parent strain (Fig. 2D).

The same experiment was performed with the S. erythraea red variant wild-type strain FL1347 and the corresponding eryBI deletion strain FL2296, also made with pFL2191. Similar results were obtained; that is, no effects on isoflavone processing were seen as a result of the eryBI mutation (data not shown).

eryBI is not required for erythromycin production in either A. erythreum or S. erythraea.

For A. erythreum, the erythromycin production by parent strain FL262 was compared with the erythromycin production by eryBI knockout strain FL2264 using the modified carbohydrate-based fermentation medium (MSCM) containing soy flour. eryBI knockout strain FL2264 produced 140 ± 15 μg/ml, which was not statistically significantly different from the amount of erythromycin produced by parent strain FL262, 190 ± 50 μg/ml (Fig. 3A).

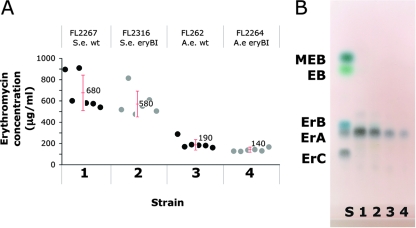

FIG. 3.

Analysis of erythromycin production by eryBI mutants of S. erythraea and A. erythreum. (A) Scatter plot showing the effect of the eryBI knockout mutation on erythromycin production in A. erythreum (A.e.) and S. erythraea (S.e.). Strain FL2267is a wild-type (wt) S. erythraea white strain; strain FL2316 is an S. erythraea eryBI knockout; FL262 is an A. erythreum wild-type strain; and strain FL2264 is an A. erythreum eryBI knockout strain. Each data point indicates the average of two measurements of erythromycin production in one shake flask. (B) TLC analysis of solvent extracts from the four cultures described above for panel A. Lane 1, S. erythraea wild-type strain FL2267; lane 2, S. erythraea eryBI mutant FL2316; lane 3, A. erythreum wild-type strain FL262; lane 4, A. erythreum eryBI mutant FL2264. Lane S contained reference standards. Abbreviations: ErA, erythromycin A; ErB, erythromycin B; ErC, erythromycin C; EB, erythronolide B; MEB, 3-O-α-mycarosyl-erythronolide B.

Erythromycin production by the S. erythraea wild-type strain and the eryBI deletion mutant in a high-production oil-based medium (OFM1) (15) was also determined. Shake flask fermentations performed in triplicate revealed that the average value obtained for parent strain FL2267 was 680 ± 170 μg/ml, compared to the 580 ± 120 μg/ml obtained for eryBI mutant strain FL2316. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference in erythromycin production between the eryBI mutant and the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A). These results for S. erythraea confirmed results obtained previously (4).

TLC analysis of extracts of broth from both fermentations (Fig. 3B) showed that primarily erythromycin A was present. No evidence of accumulation of erythronolide B or any other erythromycin biosynthetic intermediate was seen for either organism.

The same experiment was performed with S. erythraea red variant strain FL1347 and an eryBI deletion derivative of FL1347 (FL2296). FL2296 was constructed by gene replacement using pFL2191. Similar results were obtained; that is, no effect on erythromycin production was seen as a result of the eryBI mutation (data not shown).

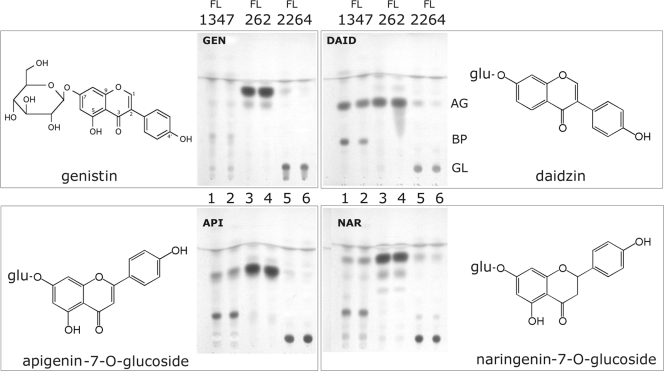

In A. erythreum, EryBI can convert other classes of flavonoid glucosides to the aglycones.

A. erythreum wild-type strain FL262, A. erythreum eryBI knockout strain FL2264, and S. erythraea red variant strain FL1347 were grown for 24 h in SCM medium not supplemented with soy flour but supplemented with 25 μg/ml flavonoid glucosides. The results of a TLC analysis are shown in Fig. 4. When daidzein was used as an example, the results showed that the spot corresponding to daidzin (the glucoside form) was the same after the 24-h incubation period for duplicate eryBI mutant strains (FL2264) (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6). The spot corresponding to daidzein (the aglycone form) appeared in the extract from wild-type strain FL262 (lanes 3 and 4), indicating that the wild-type strain was capable of completely converting the glucoside daidzin to the aglycone daidzein. The wild-type S. erythraea red variant strain was also able to convert all four glucosides to aglycones but further converted the aglycone to a new spot (spot BP) that was between the glucoside and aglycone spots (S. erythraea white strain FL2267 also performed the same conversion of the aglycone [data not shown]). Identification of this spot as an aglycone conversion product is the subject of another study (unpublished results). The glucoside form of each structure is shown next to the TLC results in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

(A) TLC analysis of A. erythreum wild-type strain FL262 and A. erythreum eryBI knockout strain FL2264 grown in medium supplemented with flavonoid glucosides, as well as S. erythraea wild-type red variant strain FL1347. Each MSCM culture was spiked with 25 μg/ml of the flavonoid glucoside and harvested after 24 h (see Materials and Methods). The four panels show the results for the three strains fed different glucosides, as follows: GEN, genistein-7-O-β-glucoside (isoflavone); DAID, daidzein-7-O-β-glucoside (isoflavone); API, apigenin-7-O-β-glucoside (flavone); and NAR, naringenin-7-O-β-glucoside (flavanone). The chemical structures of the glucosides are shown. The glucosides used were all derivatives in which glucose was attached via a 7-O-β-glucosidic linkage. In the diadzin (DAID) panel, AG indicates the location of the aglycone (daidzein) spot, BP indicates the location of the unknown daidzein bioconversion product spot, and GL indicates the location of the glucoside (daidzin) spot. Spots on the three other TLCs exhibit similar migration patterns; the only exception is the genistin BP spot for strain FL1347, which was not clearly visible at this time point but was clearly visible at earlier time points (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study we found that in A. erythreum the EryBI β-glucosidase is responsible for the conversion of isoflavone glucosides to the corresponding aglycones during erythromycin fermentation. This was determined by knocking out eryBI by plasmid insertion and observing that this was sufficient to block the isoflavone conversion reaction. Previously, eryBI had no known function in A. erythreum or S. erythraea, although it was suggested, based on its high degree of identity to oleR, that eryBI could be an erythromycin resistance gene that had become nonfunctional when the organism acquired the more effective resistance gene ermE (11). With the results presented here it is now apparent that the eryBI gene is actively expressed, and its gene product has broad substrate specificity for flavonoid glucosides, which was unexpected for an enzyme encoded in a macrolide biosynthetic gene cluster.

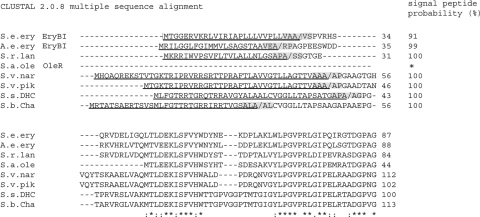

Although it is now apparent that the eryBI gene of A. erythreum is functional and that the EryBI proteins of both A. erythreum and S. erythraea show strong evidence of signal peptides (unlike the results of a previous analysis [4]) (Fig. 5), it seems unlikely that the conversion of flavonoid glucosides is the only (or the primary) function of A. erythreum EryBI, particularly since there does not appear to be an obvious connection between isoflavone metabolism and macrolide antibiotic biosynthesis.

FIG. 5.

ClustalW2 alignment (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html) and SignalP 3.0 analysis (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) of EryBI and its closest homologs in the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). SignalP 3.0 (3) determined the cleavage site of the signal peptide. The signal peptide is underlined, and the cleavage site is indicated by a forward slash in the amino acid sequence. Abbreviations: S.e.ery, S. erythraea erythromycin (accession number YP_001102999 [EryBI]; 100% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); A.e.ery, A. erythreum erythromycin (accession number AAU93797 [EryBI]; 71% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); S.r.lan, Streptomyces rochei lankamycin (accession number NP_851452; 65% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); S.a.ole, S. antibioticus oleandomycin (accession number AAC12650 [OleR]; 61% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); S.v.nar, Streptomyces venezuelae narbomycin (accession number AAM88355; 55% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); S.v.pik, S. venezuelae pikromycin (accession number AAC68679; 55% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); S.s.DHC, Streptomyces sp. strain KCTC0041BP dihydrochalcomycin (accession number ABB52530; 55% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence); S.b.Cha, Streptomyces bikiniensis chalcomycin (accession number AAS79445; 56% identity to the S. erythraea EryBI amino acid sequence). The analyses were performed in September 2008. Using the current GenBank annotation for the OleR protein sequence, no evidence for a signal peptide was found by SignalP 3.0; however, OleR has been reported to be secreted (10), and our analysis of the region upstream of the currently annotated sequence of oleR shows a high probability that it could code for a signal peptide for OleR.

There could be other functions of EryBI that have not been found yet or that are associated with a processed form of this protein. The members of the EryBI family of proteins have a multifunctional domain structure (Fig. 1) that, at least in the case of OleR, has been found to retain the oleandomycin glucosidase activity even after extracellular processing from a 87-kDa protein to a 34-kDa protein (10). Also, because eryBI homologs are conserved among many macrolide gene clusters, it is possible that the eryBI family of genes does play a role in macrolide biosynthesis under conditions that have not been tested yet. For these reasons we suggest a return to the original designation, eryBI, until the genes in this family have been more thoroughly studied and their functions are understood better.

In S. erythraea, eryBI knockout did not block the bioconversion of isoflavone glucosides, leaving open the possibility that other β-glucosidases are responsible or contribute to the metabolism of isoflavone glucosides. Attempts were made to determine whether the S. erythraea eryBI gene was functional through heterologous expression in E. coli, but plasmid clones containing the eryBI gene were too unstable in E. coli to answer this question (unpublished results). Six other genes encoding β-glucosidases have been identified in the genome of S. erythraea (SACE_1247, SACE_1284, SACE_1589, SACE_4101, SACE_5452, and SACE_6502) (8), and two of these genes (SACE_1284 and SACE_5452) were stably cloned and expressed in E. coli and found to encode β-glucosidase activity with genistin (unpublished results). If a strain of S. erythraea in which isoflavone glucoside conversion is blocked can eventually be constructed, it will most likely have to be engineered to have mutations in at least these two β-glucosidase genes as well as eryBI.

Our results also showed that eryBI knockout had no statistically significant effect on erythromycin production in either organism. This confirms previous reports that eryBI is not required for erythromycin production in S. erythraea (4, 18), and this conclusion is now extended to A. erythreum.

Finally, the primary purpose of this study was to study the effect of eryBI on isoflavone metabolism, and in this regard the results show that the EryBI β-glucosidase of A. erythreum can convert not only isoflavone glucosides but also flavone and flavonone glucosides to the corresponding aglycones. We also found that the metabolism of flavonoid compounds by A. erythreum stops after the formation of the aglycone. This means that the wild-type A. erythreum fermentation using strain FL262 would generate isoflavone aglycones as coproducts, and the A. erythreum eryBI fermentation with strain FL2264 would generate isoflavone glucosides as coproducts.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the commercially important S. erythraea strain, in which the eryBI mutation does not stop the conversion of isoflavone glucosides. Furthermore, the metabolism of isoflavones does not stop with the formation of the aglycones in S. erythraea; the organism continues to create additional biotransformation products, based on the appearance of new spots that can be visualized by TLC (Fig. 4). We have begun an investigation of aglycone bioconversion and are continuing to further characterize the other components of the isoflavone glucoside bioconversion process in S. erythraea.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant CA093165 from the National Cancer Institute and by the U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Technology Small Business Innovation Research Program.

We acknowledge Ben Leach and Roy Wesley for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee, S., Y. Li, Z. Wang, and F. H. Sarkar. 2008. Multi-targeted therapy of cancer by genistein. Cancer Lett. 269:226-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brikun, I. A., A. R. Reeves, W. H. Cernota, M. B. Luu, and J. M. Weber. 2004. The erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Aeromicrobium erythreum. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31:335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuelsson, O., S. Brunak, G. von Heijne, and H. Nielsen. 2007. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP, and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2:953-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaisser, S., G. A. Bohm, M. Doumith, M. C. Raynal, N. Dhillon, J. Cortes, and P. F. Leadlay. 1998. Analysis of eryBI, eryBIII and eryBVII from the erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Mol. Gen. Genet. 258:78-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hessler, P. E., P. E. Larsen, A. I. Constantinou, K. H. Schram, and J. M. Weber. 1997. Isolation of isoflavones from soy-based fermentations of the erythromycin-producing bacterium Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47:398-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 7.Meeran, S. M., and S. K. Katiyar. 2008. Cell cycle control as a basis for cancer chemoprevention through dietary agents. Front. Biosci. 13:2191-2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliynyk, M., M. Samborskyy, J. B. Lester, T. Mironenko, N. Scott, S. Dickens, S. F. Haydock, and P. F. Leadlay. 2007. Complete genome sequence of the erythromycin-producing bacterium Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL23338. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:447-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perabo, F. G. E., E. C. Von Löw, J. Ellinger, A. von Rücker, S. C. Müller, and P. J. Bastian. 2008. Soy isoflavone genistein in prevention and treatment of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 11:6-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quiros, L. M., C. Hernandez, and J. A. Salas. 1994. Purification and characterization of an extracellular enzyme from Streptomyces antibioticus that converts inactive glycosylated oleandomycin into the active antibiotic. Eur. J. Biochem. 222:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quirós, L. M., I. Aguirrezabalaga, C. Olano, C. Méndez, and J. A. Salas. 1998. Two glycosyltransferases and a glycosidase are involved in oleandomycin modification during its biosynthesis by Streptomyces antibioticus. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1177-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawlings, B. J. 2001. Type I polyketide biosynthesis in bacteria. Part A. Erythromycin biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18:190-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves, A. R., G. Weber, W. H. Cernota, and J. M. Weber. 2002. Analysis of an 8.1-kb DNA fragment contiguous with the erythromycin gene cluster of Saccharopolyspora erythraea in the eryCI-flanking region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3892-3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves, A. R., W. H. Cernota, I. A. Brikun, R. K. Wesley, and J. M. Weber. 2004. Engineering precursor flow for increased erythromycin production in Aeromicrobium erythreum. Metab. Eng. 6:300-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves, A. R., I. A. Brikun, W. H. Cernota, B. I. Leach, M. C. Gonzalez, and J. M. Weber. 2006. Effects of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase gene knockouts on erythromycin production in carbohydrate-based and oil-based fermentations of Saccharopolyspora erythraea. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33:600-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 17.Weber, J. M., C. K. Wierman, and C. R. Hutchinson. 1985. Genetic analysis of erythromycin production in Streptomyces erythreus. J. Bacteriol. 164:425-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber, J. M., J. O. Leung, G. T. Maine, R. H. Potenz, T. J. Paulus, and J. P. DeWitt. 1990. Organization of a cluster of erythromycin genes in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. J. Bacteriol. 172:2372-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]