Abstract

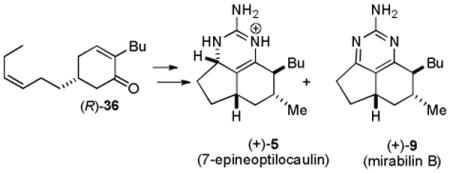

Addition of guanidine to a 6-methylhexahydroindenone in MeOH at reflux afforded 7-epineoptilocaulin. A similar reaction with a 6-propylhexahydroindenone afforded netamine E. MnO2 oxidation of 7-epineoptilocaulin and netamine E afforded mirabilin B and netamine G, respectively. The netamines have the side chains trans, not cis as was initially proposed. A unified biosynthetic scheme for the batzelladines and ptilocaulin family is proposed. Conjugate addition of guanidine to a bis enone followed by an intramolecular Michael reaction of the enolate to the other enone, aldol reaction, dehydration and enamine formation will lead to a tricyclic intermediate at the dehydroptilocaulin oxidation state. 1,4-Hydride addition will lead to ptilocaulin or 7-epineoptilocaulin depending on which face the hydride adds to. 1,2-Hydride addition will lead to isoptilocaulin. The key tricyclic intermediate was prepared from a tetrahydroindenone and guanidine and reduced with NaBH4 to give a mixture rich in ptilocaulin and isoptilocaulin.

Introduction

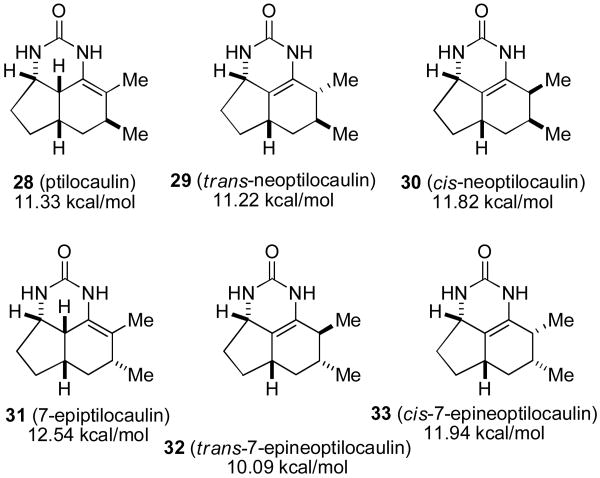

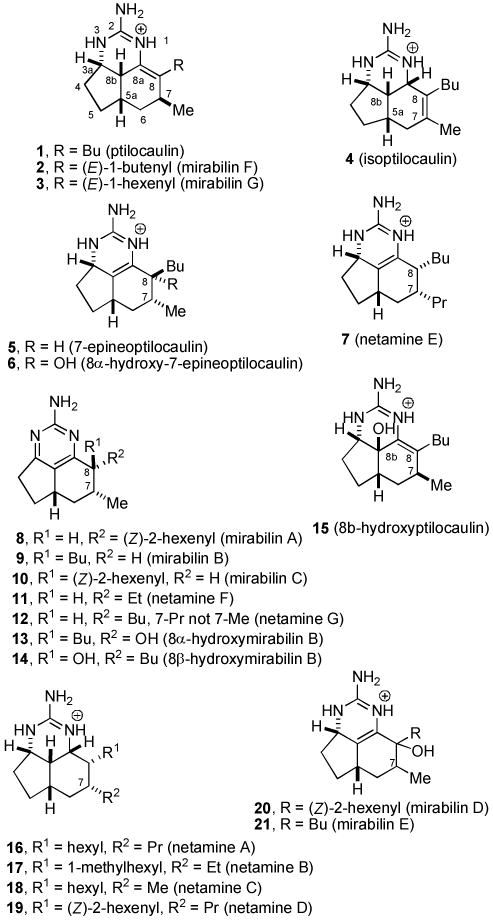

Ptilocaulin (1) and isoptilocaulin (4) were isolated by Rinehart from two different samples of Ptilocaulis aff. P. spiculifer collected at slightly different locations and depths in 1981 (see Chart 1).1a The structures were initially determined by NMR experiments. An X-ray structure determination of ptilocaulin (1) established that H-5a and H-8b are cis despite the 10 Hz coupling constant between them. Isoptilocaulin (4) also has the same stereochemistry at C-5a,1b although it was also originally depicted as the trans isomer on the basis of the large coupling constant.1a Both ptilocaulin (1) and isoptilocaulin (4) have been re-isolated from this and related sponges along with the more complex batzelladines, ptilomycalins, and crambescidins.2 Since 1995, nineteen additional members of this family of tricyclic guanidine alkaloids have been isolated from a variety of other marine sponges. Braekman isolated 8b-hydroptilocaulin (15) from Monanchora arbuscula.3 Capon isolated mirabilins A-F (8, 9, 10, 20, 21, and 2) as their N-acetyl derivatives from Arenochalina mirabilis in 1996.4 Patil and Freyer isolated mirabilin B (9), 8α-hydroxymirabilin B (13), and compounds 5 and 6 from Batzella sp. in 1997.5 Compound 5, which they called 8a,8b-dehydroptilocaulin is epimeric to ptilocaulin at C-7. It is at the same oxidation state as ptilocaulin so the dehydro prefix is incorrect. We have renamed this compound as 7-epineoptilcaulin, with the neo prefix used to indicate a double bond between C-8a and C-8b because the iso prefix was already used to indicate a double bond between C-7 and C-8. Using this system, compound 6 is named 8α-hydroxy-7-epineoptilocaulin. Capon isolated mirabilin G (3) from a Clathria sp. in 2001.6 Hamann isolated mirabilin B (9) and both 8α- and 8β-hydroxymirabilins (13 and 14) from Monanchora unguifera.7 Finally, Kashman isolated netamines A-G (16-19, 7, and 11-12) from Biemna laboutei in 2006.8

Chart 1.

Structures of the ptilocaulin (1) family.

Most of these compounds have 7-epi stereochemistry; only mirabilin F (2), mirabilin G (3), and 8b-hydroxyptilocaulin (15) have the same C-7 stereochemistry as ptilocaulin (1). Mirabilins A (8), B (9), and C (10), and netamines F (11) and G (12) are more highly oxidized with an aromatic 2-aminopyrimidine ring. Netamines A-D (16-19) are more highly reduced with a tetrahydro-2-aminopyrimidine ring. Compounds 6, 15, 20 and 21 are hydroxylated at the dihydro-2-aminopyrimidine oxidation state, while 13 and 14 are hydroxylated at the aromatic 2-aminopyrimidine oxidation state. In the aromatic series or with the double bond between C-8a and C-8b as in the neoptilcaulins, two stereoisomers are possible at C-8. The side chains are trans in 7-epineoptilocaulin (5), mirabilin B (9), and mirabilin C (10). The side chains were assigned to be cis in mirabilin A (8) on the basis of a 7-9% NOE enhancement between H-7 and H-8.4 The cis stereochemistry in all the netamines (16-19, 7, 11, 12) was also assigned based on an NOE between H-7 and H-8.8

Several members of this family have significant biological activity. Ptilocaulin (1) and isoptilocaulin (4) have ID50s of 0.39 and 1.4 μg/mL, respectively, against L1210 leukemia cells and 1 has a minimum inhibitory concentration of 3.9 μg/mL against Streptococcus pyogenes.1 Ptilocaulin (1) showed a fairly broad spectrum of in vitro activity against colon and mammary adenocarcinomas, melanomas, leukemias, transformed fibroblasts and normal lymphoid cells with IC50s of 0.05 to >10 μg/mL.9 Mirabilin B (9) exhibited antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans with an IC50 value of 7.0 μg/mL and antiprotozoal activity against Leishmania donovani with an IC50 value of 17 μg/mL. A mixture of 13 and 14 is active against the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum with an IC50 value of 3.8 μg/mL.7

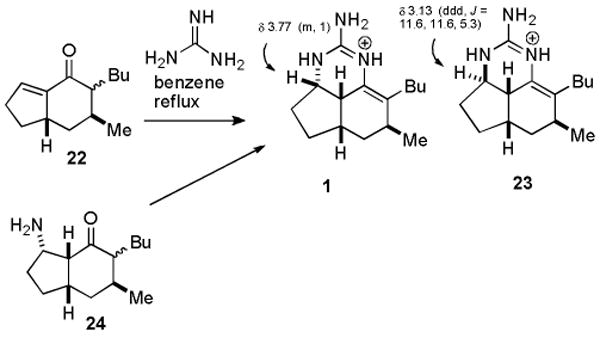

We reported the first synthesis of ptilocaulin (1) in 1983 by the reaction of bicyclic enone 22 with guanidine in benzene at reflux (see Scheme 1).10 Under equilibrating conditions, conjugate addition occurs from the desired α-face and enamine formation affords the desired double bond between C-8 and C-8a. Addition of nitric acid affords ptilocaulin nitrate identical to the natural product.10 Roush prepared amino ketone 24 and converted it to a guanidine which led to a mixture of tricyclic products. Heating the mixture in benzene at reflux, as in the reaction of 22 with guanidine, resulted in the equilibration of this tricyclic mixture to give ptilocaulin (1).11 Several more recent ptilocaulin syntheses prepared 22 by alternate methods and completed the synthesis by reaction with guanidine as we described.12-16

Scheme 1. Syntheses of Ptilocaulin (1).

Although minor stereo- or double bond position isomers are also formed from the reaction of 22 with guanidine, they were not characterized with the exception of 23. Schmalz found that 23 co-crystallized with ptilocaulin and the structure was determined crystallographically.16 It is noteworthy that 23 is formed by the presumably kinetic addition of guanidine to the less hindered top convex face of 22, whereas ptilocaulin is formed by the presumably thermodynamic addition of guanidine to the more hindered bottom face of 22.

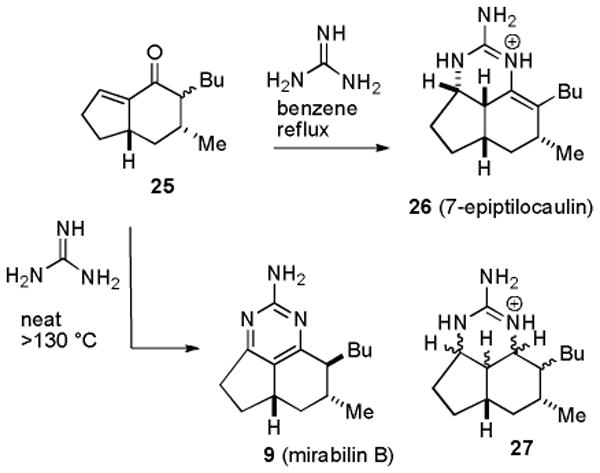

In 1986, Hassner prepared a mixture of 22, which he converted to ptilocaulin, and 25, which was treated with guanidine in benzene at reflux to give a compound he characterized as 7-epiptilocaulin (26) (see Scheme 2).13 The 1H and 13C NMR spectral data of 26 in CDCl3 are very similar to those reported in 1997 for 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) in CD3OD.5 This suggests that the position of the double bond of Hassner's product 26 has been incorrectly assigned. However, no definitive conclusions can be drawn because the spectra were recorded in different solvents. Heating 25 with guanidine neat at >130 °C resulted in disproportionation to give a mixture of an aromatic compound that is probably mirabilin B (9) and a saturated compound 27 as only one of 16 possible stereoisomers.13b Unfortunately, the 1H and 13C NMR spectral data of Hassner's aromatic compound were recorded in CDCl3 in 1991, whereas those of natural mirabilin B (9) were recorded in CD3OD in 1997.5

Scheme 2. Hassner's Studies with Hexahydroindenone 25.

Results and Discussion

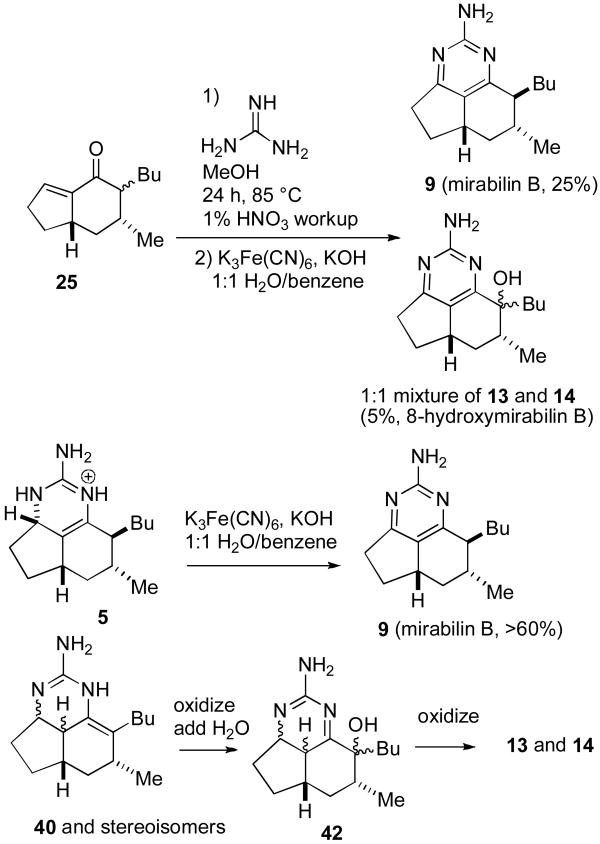

We decided to develop a practical, efficient, and stereospecific route to optically pure 25 and to unambiguously determine whether reaction with guanidine afforded 7-epiptilocaulin (26) or 7-epineoptilocaulin (5). We also wanted to explore routes to the aromatic, tetrahydroaromatic and hydroxylated members of this growing family of tricyclic alkaloids. Ptilocaulin (1) and mirabilins F (2) and G (3) with a 7β-methyl group have the double bond between C-8 and C-8a, whereas 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) and netamine E (7) with a 7α-alkyl group have the double bond between C-8a and C-8b. We therefore started by considering the effect of the stereochemistry of the 7-alkyl group on the stability of the three possible tricyclic enamines. MMX calculations were performed on ureas, which are better paramaterized than guanidinium cations, with side chains truncated to methyl groups to minimize rotational freedom.17

The ptilocaulin-like urea 28 is calculated to be 0.11 kcal/mol less stable than the trans-neoptilocaulin-like urea 29 (see Chart 2). However the 7-epiptilocaulin-like urea 31 is calculated to be 2.45 kcal/mol less stable than the trans-7-epineoptilocaulin-like urea 32. Both cis-neoptilocaulin isomers 30 and 33 are less stable than the corresponding trans-neoptilocaulin isomers 29 and 32. The 0.11 kcal/mol calculated energy difference between 28 and 29 is so small that it is not surprising that 28 is experimentally observed to be more stable. However changing the C-7 methyl group stereochemistry makes the trans-7-epineoptilocaulin-like urea 32 much more stable than the 7-epiptilocaulin-like urea 31 suggesting that the change in double bond position in the 7-epi series results from thermodynamic rather than enzymatic control.

Chart 2.

Calculated energies of ptilocaulin- and neoptilocaulin-like ureas.

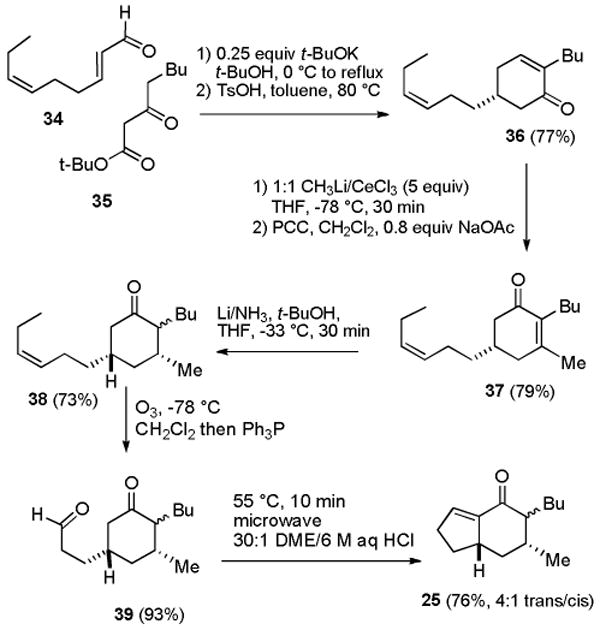

We developed a six-step route to indenone 25 starting from 2E,6Z-nonadienal (34), which contains a double bond that serves as a latent aldehyde and is readily available because of its valuable fragrance properties (see Scheme 3).18 Michael addition19 of tert-butyl 3-oxooctanoate (35)20 to dienal 34 followed by aldol reaction with 0.25 equiv of KO-t-Bu in t-BuOH at 0 °C to reflux afforded a keto ester that was hydrolyzed and decarboxylated with TsOH in toluene at 80 °C to provide cyclohexenone 36 in 77% yield. Addition of excess MeLi and CeCl321 afforded the tertiary allylic alcohol, which was treated with PCC in CH2Cl2 containing 0.8 equiv of NaOAc to give 79% of cyclohexenone 37.22 House reported that Birch reduction of 3,5-dimethyl-2-cyclohexenone afforded cis-3,5-dimethylcyclohexanone containing 6-12% of the trans isomer.23 We therefore expected that Birch reduction of 37 would control the stereochemistry at C-3. Reduction of 37 with Li in NH3 containing 9 equiv of t-BuOH at −33 °C afforded 38 in 73% yield as an irrelevant 10:1 mixture of stereoisomers at the butyl group. Minor amounts of the two isomers with a β-methyl group at C-3 are probably also formed, but analysis is complicated by the mixture of isomers at C-2. Ozonolysis of the side chain double bond followed by reduction of the ozonide with Ph3P provided aldehyde 39 in 93% yield. Intramolecular aldol reaction was most effectively carried out in a 30:1 mixture of DME/6 M aqueous HCl at 55 °C under microwave irradiation for 10 min to give 25 in 76% yield as a 4:1 mixture of isomers.10 Poorer results were obtained in THF, which has been widely used in intramolecular aldol reactions that form 22.15,24

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Hexahydroindenone 25.

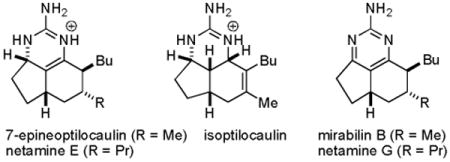

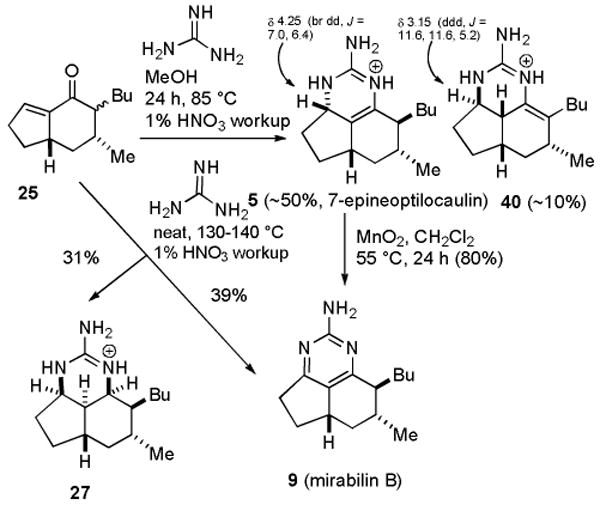

Treatment of 25 with guanidine in benzene at reflux gave mixtures containing 7-epineoptilocaulin (5). Better results were obtained with guanidine in MeOH25 at 85 °C in a sealed tube for 24 h followed by workup with 1% nitric acid, which led to 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) in ∼50% yield, 3a,7-bisepiptilocaulin (40) in 10% yield, and minor isomers with absorptions for H-3a at δ 4.01 to 3.66 that were not characterized (see Scheme 4). The 1H and 13C NMR spectral data of synthetic 5 in CD3OD are identical to those reported by Patil and Freyer5,26 and the data in CDCl3 are identical to those reported by Hassner for 7-epitilocaulin (26)13 whose structure should therefore be revised to 7-epineoptilocaulin (5). H-3a of 5 absorbs at δ 4.25, considerably downfield from δ 3.77 of ptilocaulin (1), as expected for an allylic hydrogen. H-3a of a minor isomer that was not obtained in pure form absorbs at δ 3.15 (ddd, J = 11.6, 11.6, 5.2 Hz). The structure is tentatively assigned as 40, based on the very similar chemical shift and coupling pattern for H-3a of 23 at δ 3.13 (ddd, J = 11.6, 11.6, 5.3 Hz).16,27

Scheme 4. Synthesis of 7-Epineoptilocaulin and Mirabilin B.

Oxidation of 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) with activated MnO228 in CH2Cl2 at 55 °C in a sealed tube for 1 d afforded mirabilin B (9) in 80% yield. Heating 25 with guanidine neat for 4 h at 130-140 °C followed by workup with 1% HNO3 afforded mirabilin B (9) in 39% yield and 27 in 31% yield as described by Hassner.13b The NMR spectral data of synthetic 9 in CDCl3 are identical to those reported by Hassner13b and the data in CD3OD are identical to those reported for natural mirabilin B5 establishing that synthetic 9 is mirabilin B.

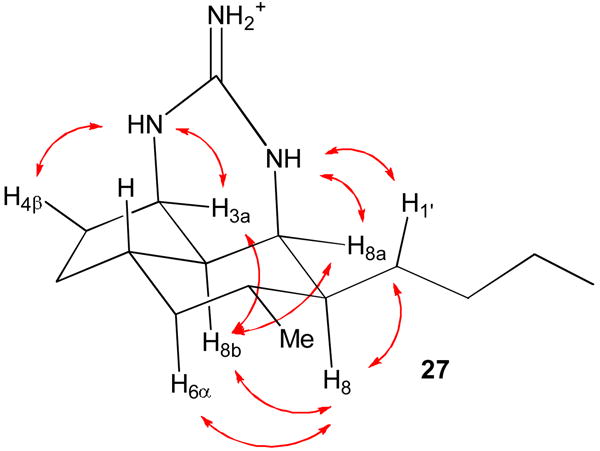

Remarkably, tricycle 27 is formed as one of sixteen possible stereoisomers. The spectral data for 27 are quite different from those of saturated netamines A-D (16-19) indicating that the stereochemistry is different. H-3a absorbs at δ 3.79 (br dd, J = 5.6, 5.6 Hz) and H-8a absorbs at δ 3.77 (br dd, J = 2.7, 2.7 Hz). H-3a, H-8a, H-8b are on the same face of the ring because a large coupling constant would be observed if either H-3a or H-8a was trans to and therefore in a diaxial orientation relative to H-8b. This restricts the sixteen possible isomers to only four. These three hydrogens can be all up or all down and the butyl group can be either cis or trans to the methyl group. Protons and carbons in CDCl3 were assigned on the basis of COSY, HMQC, and HMBC experiments at 800 MHz (see Table S1 in the supporting material). A ROESY experiment showed NOEs between H-8b and both H-3a and H-8a confirming that they are all on the same face of the molecule as expected from the analysis of coupling constants. NOEs between H-8 and both H-6α and H-8b establish that all these hydrogens are on the α-face. NOEs were also observed between NH-1 at δ 7.63 and the side chain hydrogens H-1′ at δ 1.52 and 1.70 and between NH-3 at δ 8.2 and H-4β at δ 1.72 confirming the stereochemical assignment shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

MMX-calculated structure of 27 with NOEs shown that establish the stereochemistry.

Compounds 27 and mirabilin B (9) are presumably formed by disproportionation of intermediates at the oxidation state of 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) as suggested by Hassner. It is quite surprising that the stereochemistry of 27 at C-3a is the opposite of that of 5 and identical to that of the minor byproduct 40. 7-Epineoptilocaulin (5) is clearly formed under thermodynamic conditions. A kinetically formed intermediate with the C-3a stereochemistry of 40 must undergo reduction in the disproportionation reaction more readily than intermediates with the C-3a stereochemistry of 5.

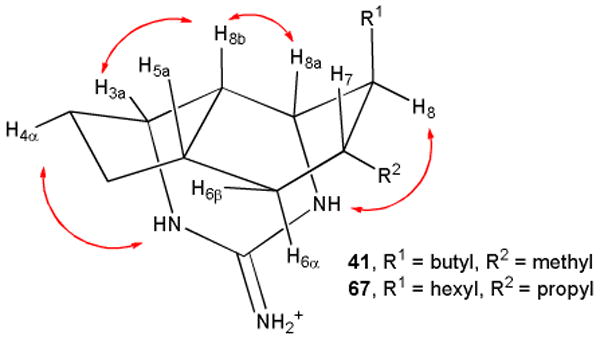

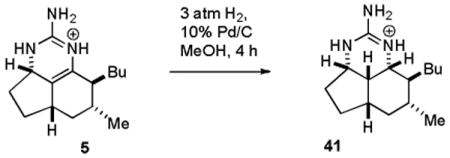

Kashman reported that hydrogenation of netamine E (7) over Pd/C afforded a compound with the same stereochemistry as netamines A-D (16-19).8 We therefore hydrogenated 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) over Pd/C under 3 atm of H2 for 4 h to give saturated tricyclic guanidine 41 in ∼90% yield (see equation 1). As expected, the spectral data for 41 were quite different from those of the stereoisomer 27 obtained in the disproportionation reaction. We therefore assigned all the protons and carbons in 41 in CDCl3 as shown in Table S1 in the supporting material on the basis of COSY, HMQC, and HMBC experiments at 800 MHz. H-3a absorbs at δ 3.89 (br dd, J = 6, 4.2 Hz) and H-8a absorbs at δ 3.54 (br dd, J = 4.9, 1.1 Hz). As in 27, H-3a, H-8a, H-8b are on the same face of the ring because a large coupling constant would be observed if either H-3a or H-8a was trans to and therefore in a diaxial arrangement with H-8b. A ROESY experiment showed NOEs between H-8b and both H-3a and H-8a confirming that they are all on the same face of the molecule as expected from the analysis of coupling constants. The cyclohexane ring is calculated to be a boat (see Figure 2) making H-6α and H-8 3.52 Å apart so that no NOE is observed. However, the guanidinium nitrogens are observed as three separate peaks in CDCl3. The NOE observed between NH-1 at δ 7.64 and H-8 at δ 1.46 confirms that side chains in 41 are trans.

Figure 2.

MMX-calculated structures of 41 and 67 with NOEs shown that establish the stereochemistry.

|

(1) |

The spectral data of saturated tricyclic guanidine 41 are remarkably similar to those of netamines A-D (16-19) in which the side chains are reported to be cis rather than trans as in 41. The spectral data of 41 are virtually identical to those of netamine C (18), which has a hexyl rather than a butyl group on C-8 (see Table S1 in the supporting material). The stereochemistry of netamines A (16), C (18), E (7), and G (12) was therefore reexamined and established to be trans as discussed below.

We now turned our attention to the preparation of hydroxylated members of this family. Oxidation of 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) with K3Fe(CN)629 in aqueous KOH and benzene afforded only mirabilin B (9). However treatment of 25 with guanidine in MeOH in a sealed tube in an 85 °C oil bath and oxidation of the crude product mixture with K3Fe(CN)6 as described above afforded mirabilin B (9) in 25% yield and a 1:1 mixture of 8-hydroxymirabilins B (13 and 14) in 5% yield (see Scheme 5). The spectral data of this 1:1 mixture are identical to those of the 1:1 mixture isolated by Hamann.7,30 We suspect that 13 and 14 are formed by hydroxylation and oxidation of minor components of the mixture with the enamine double bond between H-8 and H-8a as in ptilocaulin, such as 40, to give 42 and then 13 and 14. Neither 5 nor 9 can be intermediates in the formation of 13 and 14 because oxidation of 5 affords only mirabilin B (9). Dioxiranes have been reported to effect benzylic hydroxylations.31 Unfortunately treatment of 9 with dimethyldioxirane afforded no 13 and 14 and a complex mixture that appeared to contain N-oxides, which are known to be readily formed from 2-aminopyrimidines.32

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Hydroxymirablins (13 and 14).

Synthesis of (+)-7-epineoptliocaulin (5) and (+)-mirabilin B (9)

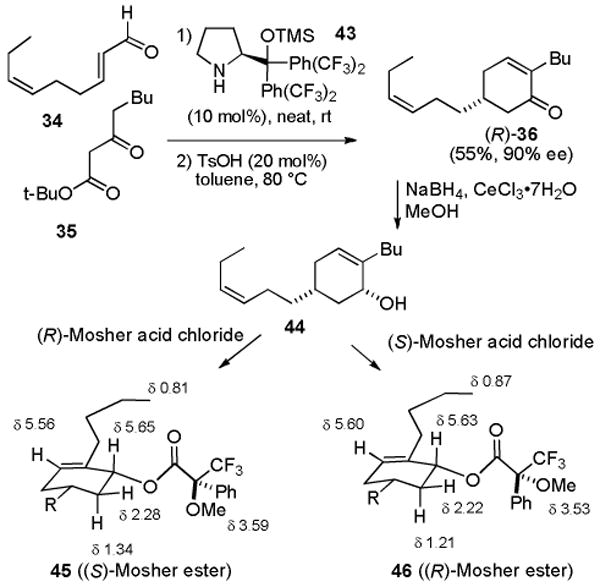

The syntheses described above were carried out in the racemic series because the Michael reaction of 34 and 35 afforded cyclohexenone 36 as a racemic mixture. Jørgensen recently reported an asymmetric organocatalytic protocol for such Michael reactions.33 Reaction of 34 and 35 neat with 10 mol% catalyst 43 and then treatment with 20 mol% p-toluenesulfonic acid in toluene at 80 °C afforded (R)-36 in 55% yield and 90% ee (see Scheme 6). The absolute stereochemistry was assigned by analogy to Jørgensen's examples.33 Reduction of (R)-36 with NaBH4 and CeCl3 afforded cis allylic alcohol 44 which was converted to the Mosher esters 45 and 46. This established that the ee was 90% as observed by Jørgensen in related examples. The upfield shifts of the protons proximate to the phenyl group confirmed the assignment of absolute stereochemistry.34

Scheme 6. Synthesis of (-)-(R)-36.

The same series of reactions as in the racemic series afforded (+)-7-epineoptliocaulin (5) and (+)-mirabilin B (9) (see equation 2). The optical rotation for synthetic 5, [α]D25 + 45.9, has the same sign, but is much larger than that of natural 5, [α]D + 13.3.5 The optical rotation for synthetic 9, [α]D25 + 123.6 (MeOH), has the same sign, but is much larger than that initially reported for 9, [α]D + 41.6 (MeOH).5 However the value for synthetic 9, [α]D25 + 145 (CHCl3), compares favorably with that of the mirabilin B (9) that was re-isolated in 2004, [α]D22 + 129 (CHCl3).35 The absolute stereochemical assignment of synthetic 5 and 9 is based on the expected product of the Jørgensen asymmetric Michael reaction and analysis of the NMR spectra of the Mosher esters. Therefore the absolute stereochemistry of natural 5 and 9 is as shown.

|

(2) |

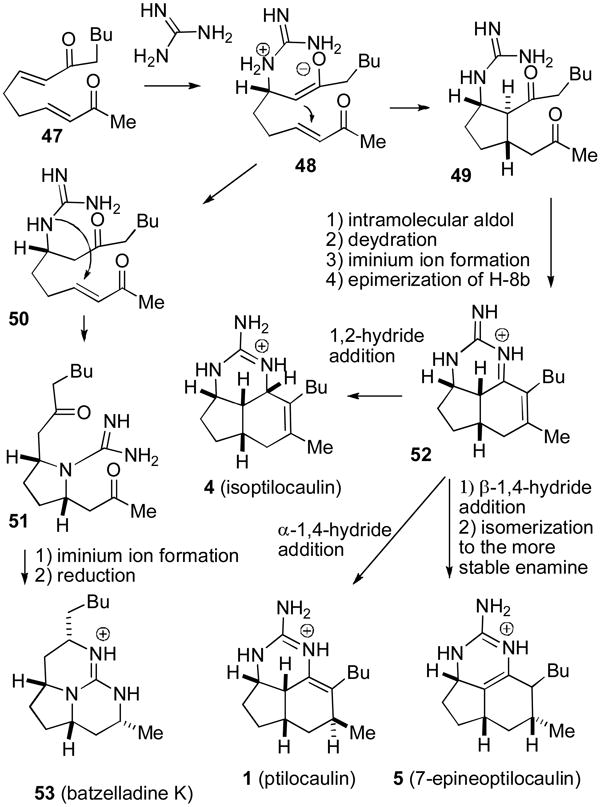

A proposal for a unified biosynthesis of the ptilocaulin and batzelladine family of alkaloids

It is possible that ptilocaulin (1) and 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) are biosynthesized by addition of guanidine to enones 22 and 25, respectively, as can be easily achieved in one pot in ∼50% yield in the laboratory. However, it is not clear how nature could adapt this route to the biosynthesis of isoptilocaulin (4), which has an allylic guanidine. Furthermore, this would require the presence of two different precursor enones in the sponge. A unified biosynthetic proposal that would lead to ptilocaulin (1), isoptilocaulin (4), 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) and the batzelladines such as batzelladine K (53) is shown in Scheme 7.

Scheme 7. Unified Biosynthetic Proposal for Ptilocaulin, Isoptilocaulin, 7-Epineoptilocaulin, and Batzelladine K.

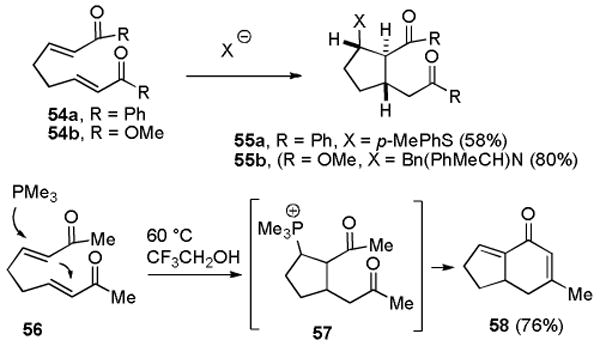

Conjugate addition of guanidine to bis enone 47 will give guanidinium enolate 48, which could undergo an intramolecular Michael addition to give cyclopentane dione 49. There are ample precedents for tandem conjugate additions leading to trans,trans-cyclopentanes analogous to 49. For example, addition of a thiophenoxide anion to bis enone 54a gave 55a in 58% yield (see Scheme 8).36 Addition of an amide anion to bis enoate 54b provided 55b in 80% yield.37 Dione 49 would have to undergo an intramolecular aldol and dehydration reaction, epimerization of H-8b, and iminium ion formation in unspecified order to give the key tricyclic intermediate 52. There is precedent for these steps in the work of Roush who reported that addition of PMe3 to bis enone 56 gives 57, which undergoes an intramolecular aldol and dehydration reaction to give bicyclic dienone 58 after elimination of PMe3.38

Scheme 8. Precedents for the Proposed Biosynthesis.

The key step in this biosynthetic scheme is the reduction of 52 which can form ptilocaulin (1), isoptilocaulin (4), and 7-epineoptilocaulin (5). 1,2-Reduction of 52 from the less hindered β-face will give isoptilocaulin (4). 1,4-Reduction from the α-face will give ptilocaulin (1). 1,4-Reduction from the β-face and isomerization to the more stable enamine in the 7-epi series will give 7-epineoptilocaulin (5).

A proton shift will convert guanidinium enolate 48 to guanidine ketone 50. An intramolecular conjugate addition of the guanidine can form pyrrolidine 51. Iminium ion formation and 1,2-reduction will give rise to batzelladine K (53). Numerous batzelladines are known with different side chains;2a batzelladine K (53) which would be formed from the same precursor as the ptilocaulin natural products was isolated in 2007.39 Reaction of guanidine with bis enones, differing from 47 only in the alkyl side chains, followed by reduction affords batzelladines analogous to 53 in excellent yields.40 It is therefore not straightforward to develop the reaction of guanidine with bis enones as a laboratory route to the ptilocaulin family of natural products.

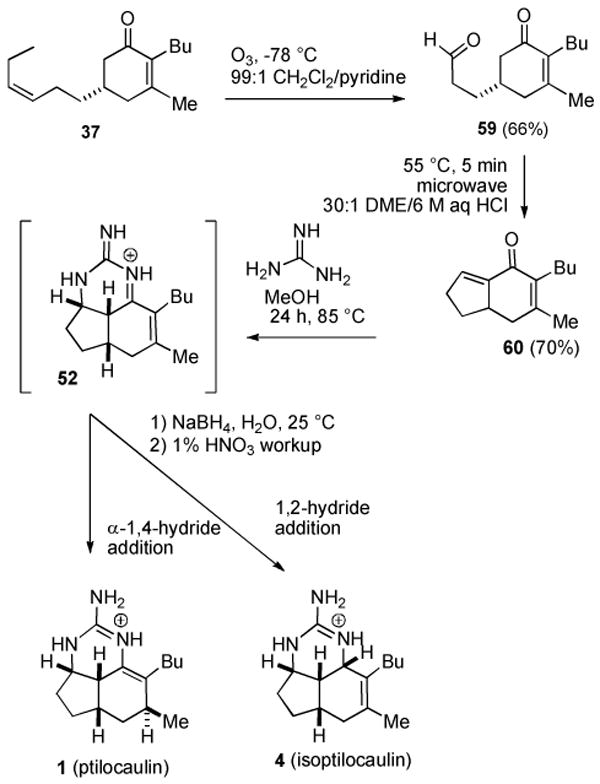

Fortunately it is fairly easy to develop an alternate route to the key intermediate 52 and explore whether reduction can lead to ptilocaulin (1), isoptilocaulin (4), and 7-epineoptilocaulin (5). The cyclohexene double bond of 52 was easily installed simply by using enone 37 without the Birch reduction that afforded 38. Selective ozonolysis of the more electron rich double bond of 37 to give 59 in 66% yield was easily accomplished in the presence of pyridine,41 which also served to reduce the ozonide (see Scheme 9). A complex mixture of products was obtained in the absence of pyridine. Intramolecular aldol reaction with 30:1 DME/6 M aqueous HCl gave bicyclic dienone 60 in 70% yield. Reaction of 60 with guanidine in MeOH in a sealed tube in an 85 °C oil bath for 24 h presumably afforded tricyclic iminium ion 52. Cooling the reaction to room temperature and addition of NaBH4 afforded an inseparable 1:1 mixture of ptilocaulin (1) and isoptilocaulin (4) and various minor byproducts completing the first synthesis of isoptilocaulin (4) and establishing the plausibility of the proposed biosynthetic route. The presence of isoptilocaulin in this mixture was established by comparison with data for the natural product.1b,2c We were frustrated by our inability to separate ptilocaulin and isoptilocaulin, but note that isoptilocaulin has only been obtained pure when it has been isolated from a source that does not also produce ptilocaulin.1,2b,2c

Scheme 9. Biomimetic Synthesis of Ptilocaulin and Isoptilocaulin.

Stereochemistry of the Netamines

The close similarity of the 1H NMR spectra of hydrogenation product 41 and netamine C (18), which has a hexyl rather than a butyl side chain, suggested that the side chains in the netamines might be trans, not cis. The stereochemistry of the netamines was assigned on the basis of an NOE between H-8 and both H-7 and H-8a in the saturated netamines A-D. However, the MMX-calculated distances17 between H-8 and both H-7 and H-8a in saturated netamines A-D (16-19) are 2.37 Å and 2.25 Å, respectively, for the cis isomer and 2.87 Å and 2.51 Å, respectively, for the trans isomer so these NOEs are inconclusive. Mirabilin A (8) was also assigned to have side chains cis based on an NOE between H-7 and H-8. In the aromatic series, the calculated distances17 are 2.28 Å for the cis isomer mirabilin A (8) and 3.08 Å for the trans isomer mirabilin C (10), which was also isolated, so this assignment seems secure. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of aromatic netamines F (11) and G (12) correspond closely to those of mirabilin B (9) and N-acetyl mirabilin C with trans side chains and differ considerably from N-acetyl mirabilin A with cis side chains (see supporting material) suggesting that these netamines also have the side chains trans.

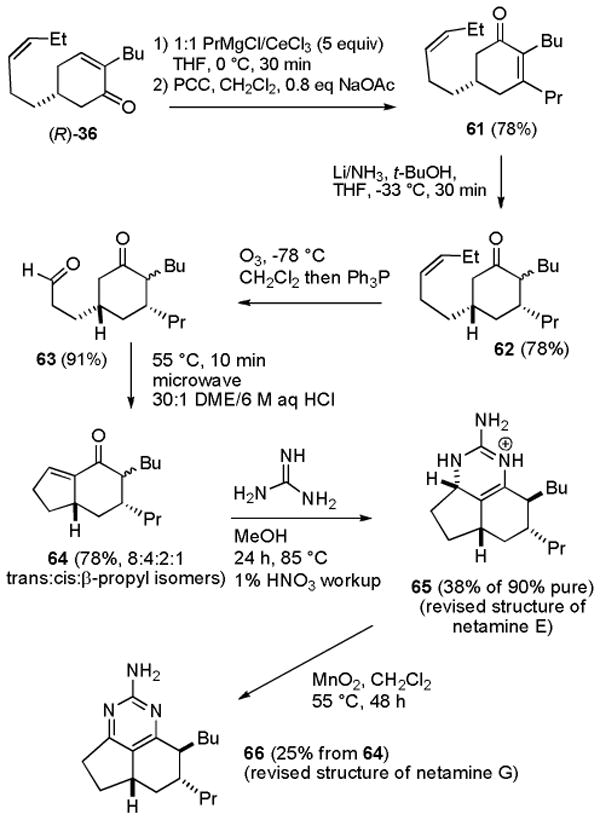

The trans isomers of netamines E (65) and G (66) should be readily accessible by a slight modification of the route used to prepare 7-epineoptilocaulin (5) and mirabilin B (9). Addition of PrMgCl and CeCl3 to (R)-36 followed by PCC oxidation afforded cyclohexenone 61 in 78% yield (see Scheme 10). Birch reduction afforded 62 in 78% yield as a 7:1 mixture of isomers at C-2. This Birch reduction is not as selective as that of 37 for the required 3,5-cis isomer, probably because of steric interactions between the larger butyl and propyl substituents. We unsuccessfully explored a variety of copper hydride conjugate reductions of 61.42 Apparently the double bond of 61 is too hindered. Ozonolysis of 62 afforded keto aldehyde 63 in 91% yield, which was treated with HCl in DME in a microwave oven at 55 °C for 10 min to give bicyclic enone 64 in 78% yield as an 8:4:2:1 mixture of trans-64, cis-64, and the two isomers with a β-propyl group, respectively. The selectivity for the trans isomer of 64 (2:1) is much lower than for the trans isomer of 25 (4:1). MMX calculations17 indicate that trans-64 is only 0.5 kcal/mol more stable than the cis isomer, whereas trans-25 is 1.2 kcal/mol more stable than the cis isomer. Bicyclic enone 64 may also contain some of the two isomers with the propyl group on the top face resulting from the less selective Birch reduction.

Scheme 10. Synthesis of Netamines E (65) and G (66).

Heating 64 with guanidine in MeOH in a sealed tube in an 85 °C oil bath for 24 h followed by neutralization with 1% HNO3 afforded a more complex mixture of products than the analogous reaction of 25. Repeated careful chromatography gave 65 that was >90% pure in 38% yield. Oxidation of the crude reaction mixture with MnO2 in CH2Cl2 in a sealed tube in a 55 °C oil bath for 48 h afforded 66 in 25% overall yield from 64.

The spectral data of 66 in CDCl3 vary significantly as a function of the amount of acid in solution as is well known for 2-aminopyrimidines.43 We titrated 66 with a solution of TFA in CDCl3 to obtain a complete set of partially protonated spectra. The spectrum of 66 in CDCl3 containing 9% TFA matched the published spectra of netamine G very well.8,44 At this degree of protonation, H-5 (δ 2.38) and H-8 (δ 2.30) are well resolved and H-8 absorbs as a ddd, J = 8.8, 4.4, 4.4 Hz, as calculated17 and observed in trans isomers mirabilin B (9) and N-acetyl mirabilin C (10).4,5 The 8.8 Hz coupling constant between H-7 and H-8 establishes that these two hydrogens are trans. With more TFA, H-5 and H-8 appear together as a broad multiplet at δ 2.40. H-8 absorbs as a ddd, J = 6, 6, 5 Hz, as calculated,17 in the cis isomer N-acetyl mirabilin A (8).4 This analysis establishes that the side chains of natural netamine G are trans and the structure should therefore be revised to 66. The rotation of synthetic netamine G (66), [α]D25 + 26.3, is identical to that of natural netamine G, [α]D21 + 27.0, establishing that the absolute stereochemistry of the natural product is as shown for 66.

The trans stereochemistry of the side chains of 65 was established by a 1D NOESY experiment in CD3OD with irradiation of axial H-6α at δ 0.77 which showed an NOE to both H-8 at δ 1.95 and the propyl CH2 group at δ 1.20 and 1.60. This analysis establishes that the side chains of natural netamine E are trans and the structure should therefore be revised to 65. The rotation of synthetic netamine E (65), [α]D25 + 15.6, has the same sign as that of natural netamine E, [α]D25 + 35.0, establishing that the absolute stereochemistry of the natural product is as shown for 65.

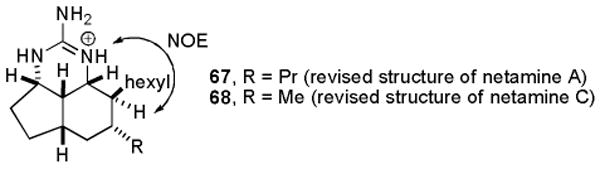

The stereochemistry of the side chains of saturated tricycle 41 was assigned by analysis of the NOEs to the NH protons, which are separately observable in CDCl3. We carried out a ROESY experiment at 800 MHz on a sample of natural netamine A (16) kindly provided by Prof. Kashman.44 NOEs between NH-1 at δ 7.76 and H-8a at δ 3.57 and H-8 at δ 1.51, but not the hexyl group H-1′ at δ 1.27, established that H-8 is down and the hexyl group is up and therefore trans to the propyl group at C-7 (see Figure 3). The structure of netamine A should therefore be revised to 67.

Figure 3.

Revised Structures of Netamines A and C.

The structures of netamines E and G have been revised to 65 and 66, respectively, on the basis of the identity of their spectra to those of the natural products. The NOE between NH-1 and H-8 of natural netamine A establishes that the side chains are trans and the structure should be revised from 16 to 67. The similarity of the spectra of 41 and netamine C, which has a hexyl rather than a butyl side chain, establishes that structure of netamine C should be revised to 68. This suggests that netamines B, D and F may also have the side chains trans with a β-alkyl group at C-8.

In conclusion, we have prepared optically pure indenone 25 in six steps in 31% overall yield and converted it to 7-epineoptilocaulin (5, ∼50%), mirabilin B (9, 39%), and 8-hydroxymirabilins (13 and 14, 5%). Optically pure indenone 64 was prepared analogously and converted to netamine E (65, 38%) and netamine G (66, 25%). These studies establish that the structures of netamines A (67), C (68), E (65), and G (66) should be revised so that the 8-alkyl group is trans to the alkyl substituent at C-7. A unified proposal for ptilocaulin, isoptilocaulin and 7-epineoptilocaulin family of alkaloids suggests that all of these natural products can be obtained by 1,2- or 1-4 reduction of tricyclic iminium salt 52, which could be formed by addition of guanidine to bis enone 47. Tricyclic iminium salt was generated in the laboratory by addition of guanidine to dienone 60. Reduction with NaBH4 generated a mixture rich in ptilocaulin (1) and isoptilocaulin (4) providing experimental support for this hypothesis.

Experimental Section

(±)-(3aS,5aS,7R,8S)-8-Butyl-1,3a,4,5,5a,6,7,8-octahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-2-amine (7-Epineoptilocaulin, 5)

A 0.18 M solution of guanidine in MeOH was prepared by adding guanidinium hydrochloride (86 mg, 0.90 mmol) to a solution of NaOMe in MeOH prepared by adding Na (21 mg, 0.90 mmol) to anhydrous MeOH (5.0 mL) under nitrogen.

Guanidine in MeOH (0.18 M, 2.5 mL, 0.45 mmol) was transferred to a resealable tube containing indenone 25 (41 mg, 0.20 mmol) in 2.5 mL of MeOH under nitrogen. The tube was sealed and heated in an 85 °C oil bath for 24 h. The mixture was cooled, quenched with 1% HNO3 (3.0 mL, 0.33 mmol) and diluted with CHCl3 (20 mL). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to yield 82 mg of crude 5 as a brown oil. Repeated flash chromatography on silica gel (20:1 CHCl3/MeOH) gave 13 mg (21%) of >95% pure 5 as a colorless oil and 23 mg (37%) of 80% pure 5 as a light yellow oil: 1H NMR (CDCl3) 8.99 (br s, 1), 8.21 (br s, 1), 7.60 (br s, 2), 4.25 (br dd, 1, J = 7.0, 6.4), 2.45-2.32 (m, 1), 2.19-2.05 (m, 1), 1.98-1.83 (m, 3), 1.82-1.51 (m, 4), 1.41-1.20 (m, 3), 1.20-1.05 (m, 2), 1.00 (d, 3, J = 6.4), 0.89 (t, 3, J = 7.2), 0.86 (ddd, 1, J = 12, 12, 12); (CD3OD) 4.27 (br dd, 1, J = 7.0, 6.4), 2.51-2.40 (m, 1), 2.25-2.12 (m, 1), 2.04-1.92 (m, 2), 1.92-1.81 (m, 1), 1.79-1.54 (m, 4), 1.40-1.20 (m, 4), 1.20-1.10 (m, 1), 1.06 (d, 3, J = 6.8), 0.93 (t, 3, J = 7.2), 0.90 (ddd, 1, J = 12, 12, 12); 13C NMR (CDCl3) 153.6, 127.9, 117.1, 52.3, 42.5, 38.9, 36.6, 32.9, 32.0, 29.7, 27.0, 25.9, 23.1, 20.0, 14.2; 13C NMR (CD3OD) 154.7, 128.7, 119.5, 53.9, 44.1, 40.1, 37.8, 33.9, 33.7, 30.6, 28.4, 27.4, 24.4, 20.4, 14.6; IR (neat) 3223, 1674, 1576, 1455, 1380; HRMS (EI) calcd for C15H25N3 (M+) 247.2048, found 247.2050.

Our 1H NMR (CD3OD) data are 0.01 to 0.02 ppm downfield and our 13C NMR (CD3OD) data are shifted by up to 0.1 to 0.2 ppm from those reported.5 The appearance of the 1H NMR spectrum in CD3OD corresponds well with an authentic spectrum provided by Dr. Alan J. Freyer.26 The spectral data in 1H NMR data in CDCl3 are identical to those reported for “7-epiptilocaulin” by Hassner. The 13C NMR data are shifted upfield by 0 to 0.2 ppm.13

The 1H NMR spectrum of the crude mixture in CDCl3 showed the presence of 40 [∼10%, δ 3.15 (ddd, 1, J = 11.6, 11.6, 5.2)] and uncharacterized isomers with peaks at δ 4.01 (br dd, 1, J = 6.4, 5.6), 3.89 (ddd, 1, J = 6.8, 5.6, 1.1), and 3.82-3.66 (m).

An identical reaction with (7aS)-25 afforded (5aS)-5: [α]D25 + 45.9 (c 0.135, MeOH); [lit.5 [α]D + 13.3 (c 1.2, MeOH)].

(±)-(5aS,7R,8S)-8-Butyl-4,5,5a,6,7,8-hexahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-2-amine (Mirabilin B, 9)

A mixture of 5 (7 mg, 0.023 mmol) and activated MnO2 (13.1 mg, 0.15 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) was stirred in a sealed tube in a 55 °C oil bath for 24 h. The mixture was cooled and filtered through Celite. The residue was washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 4 mL). The combined organic layers were concentrated to yield 7 mg of crude 9 as a yellow oil. Flash chromatography on silica gel (70:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH) gave 5.7 mg (80%) of 9 as a light yellow oil: 1H NMR (CDCl3) 4.90 (br s, 2), 2.97-2.83 (m, 2), 2.58 (dd, 1, J = 16.4, 8.8), 2.35 (ddd, 1, J = 12.4, 7.2, 7.2), 2.20 (br ddd, 1, J = 10.2, 4.4, 4.4), 2.09-1.96 (m, 2), 1.91-1.80 (m, 1), 1.80-1.69 (m, 1), 1.59-1.45 (m, 1), 1.38-1.19 (m, 3), 1.09 (d, 3, J = 6.8), 1.16-1.05 (m, 1), 0.91 (ddd, 1, J = 11.6, 11.6, 12.4), 0.87 (t, 3, J = 6.8); (CD3OD) 2.99-2.83 (m, 2), 2.55 (dd, 1, J = 16.4, 8.4), 2.38 (ddd, 1, J = 12.4, 7.2, 7.2), 2.19 (br dt, 1, J = 9.6, 4,4), 2.12-1.96 (m, 2), 1.95-1.70 (m, 2), 1.60-1.44 (m, 1), 1.38-1.19 (m, 3), 1.11 (d, 3, J = 6.8), 1.14-1.01 (m, 1), 0.91 (ddd, 1, J = 12, 12, 12), 0.88 (t, 3, J = 7.2); 13C NMR (CDCl3) 174.6, 166.1, 163.1, 126.1, 47.0, 39.7, 37.7, 34.1, 33.6, 33.1, 30.3, 27.7, 23.3, 21.0, 14.1; 13C NMR (CD3OD) 176.3, 167.6, 164.8, 126.9, 48.4, 41.0, 39.1, 35.3, 34.3, 34.3, 31.2, 28.7, 24.5, 21.4, 14.5; IR (neat) 3317, 3184, 1622, 1587, 1456, 1386; HRMS (EI) calcd for C15H23N3 (M+) 245.1893, found 245.1892.

The 1H NMR (CD3OD) data and 13C NMR (CD3OD) correspond to the literature data,5 except that our 1H NMR (CD3OD) data are 0.01 to 0.02 ppm downfield and our 13C NMR (CD3OD) data are 0.1 to 0.2 ppm downfield. The 1H NMR data in CDCl3 are identical and the 13C NMR data are within 0.1 ppm to those reported.13b

An identical reaction with (5aS)-5 afforded (5aS)-9: [α]D25 + 123.6 (c 0.09, MeOH), [α]D25 + 145 (c 0.06, CHCl3); [lit.5 [α]D + 41.6 (c 0.48, MeOH)], [lit.35 [α]D22 + 129 (c 0.1, CHCl3)].

(±)-Mirabilin B (9) and (±)-(3aR,5aS,7R,8S,8aS,8bR)-8-Butyl-1,3a,4,5,5a,6,7,8,8a,8b-decahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazoline-2-amine (27)

Guanidine in MeOH (0.18 M, 1.2 mL, 0.22 mmol) was transferred to a 50 mL flask containing indenone 25 (31 mg, 0.15 mmol). The MeOH was evaporated and the reaction mixture was heated in a 130-140 °C oil bath under nitrogen for 4 h. The solution was cooled, treated with benzene (15 mL) and 1% HNO3 (2 mL), and stirred for 30 min. The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to yield 53 mg of crude 9 and 27 as a brown oil. Flash chromatography on silica gel (70:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH) gave 18 mg (39%) of 9 as a yellow oil. Flushing the silica gel with MeOH gave 14 mg (31%) of 27.

Compound 27: 1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) 8.20 (br s, 1), 7.63 (br s, 1), 7.32 (br s, 2), 3.79 (br dd, 1, J = 5.6, 5.6), 3.77 (br dd, 1, J = 2.7, 2,7), 2.10 (m, 1), 1.98-1.85 (m, 2), 1.78-1.65 (m, 3), 1.55-1.42 (m, 4), 1.42-1.22 (m, 2), 1.22-1.10 (m, 3), 0.96 (d, 3, J = 7.2), 0.94 (t, 3, J = 8), 0.86 (ddd, 1, J = 12, 12, 12); 13C NMR 154.2, 51.6, 47.0, 46.2, 46.1, 39.6, 36.3, 32.4, 31.7, 29.1, 29.0, 27.4, 22.7, 20.1, 14.2; IR (neat) 3225, 3087, 1667, 1621, 1463, 1380; HRMS (EI) calcd for C15H27N3 (M+) 249.2205, found 249.2202.

(±)-Mirabilin B (9) and (±)-(5aS,7R,8R)- and (±)-(5aS,7R,8S)-2-Amino-8-butyl-4,5,5a,6,7,8-hexahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-8-ol ((±)-8α-hydroxymirabilin B, 13 and (±)-8β-hydroxymirabilin B, 14)

Crude 5, containing isomers (47 mg) was prepared as described above from indenone 25 (33.5 mg, 0.16 mmol). This material was taken up in water (1.9 mL) and benzene (1.9 mL). KOH (17.1 mg, 0.30 mmol) and K3[Fe(CN)6] (105 mg, 0.32 mmol) were added and the mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 16 h. The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with benzene (2 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with water, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to yield 26 mg of crude 9, 13, and 14 as a yellow oil. Flash chromatography on silica gel (70:1 ∼ 20:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH) gave 12.5mg (25%) of 9 followed by 2.8 mg (5%) of a 1:1 mixture of 13 and 14: 1H NMR 4.96 (br s, 2), 3.05-2.83 (m, 2), 2.66 (dd, 0.5 × 1, J = 17.2, 8), 2.60 (dd, 0.5 × 1, J = 17.2, 8.4), 2.44-2.27 (m, 1), 2.27-2.16 (m, 0.5 × 1), 2.10 (ddd, 0.5 × 1, J = 12.4, 12.4, 4.4), 2.08-1.98 (m, 0.5 × 1), 1.97-1.81 (m, 2), 1.76 (ddd, 0.5 × 1, J = 12.4, 12.4, 4.4), 1.71-1.47 (m, 1), 1.40 (ddd, 0.5 × 1, J = 11.6, 11.6, 12.4), 1.34-1.11 (m, 3.5), 1.17 (d, 0.5 × 3, J = 6.8), 1.06 (d, 0.5 × 3, J = 6.8), 1.01-0.72 (m, 1), 0.85 (t, 0.5 × 3, J = 7.2), 0.82 (t, 0.5 × 3, J = 7.2); 13C NMR (500 MHz) (13) 176.3, 164.7, 125.5, 75.3, 38.3, 37.2, 36.7, 35.2, 34.1, 33.5, 27.1, 23.5, 15.0, 14.0 (the peak at 163.5 was not observed); (14) 125.5, 74.1, 42.0, 37.8, 37.4, 36.8, 33.8, 33.3, 26.9, 23.1, 15.6, 13.8 (the peaks at 175.7, 163.7 and 163.2 were not observed); IR (neat) 3416, 3314, 3184, 1607, 1584, 1464, 1385; HRMS (EI) calcd for C15H23ON3 (M+) 261.1841, found 261.1842.

The 1H NMR spectral data match those of an authentic sample provided by Prof. Hamann.30 The 13C NMR spectral data match the literature data,7 except that some aromatic carbons were not observed due to the low sample concentration.

(±)-(3aS,5aS,7R,8S,8aR,8bS)-8-Butyl-1,3a,4,5,5a,6,7,8,8a,8b-decahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazoline-2-amine (41)

7-Epineoptilocaulin (5) (4.5 mg, 0.0145 mmol) in methanol (5 mL) was hydrogenated over 10% Pd/C (5 mg) for 4 h at 3 atm. The solution was filtered through Celite and concentrated to afford 5 mg (111%) of 80 % pure 41: 1H NMR (800 MHz) 7.64 (br s, 1), 7.61 (br s, 1), 7.05 (br s, 2), 3.89 (dd, 1, J = 6, 4.2), 3.54 (dd, 1, J = 4.9, 1.1), 2.34 (ddd, 1, J = 11.4, 5.7, 5.7), 2.14-2.06 (m, 1), 1.97 (ddd, 1, J = 12.9, 7.1, 7.1), 1.93 (dd, 1, J = 13.2, 5.8), 1.71-1.58 (m, 2), 1.48-1.45 (m, 1), 1.40-1.20 (m, 8), 1.13 (ddd, 1, J = 13, 13, 13), 1.09 (d, 3, J = 6.7), 0.92 (t, 3, J = 6.7); 13C NMR (800 MHz) 154.8, 53.8, 50.0, 44.7, 35.8, 35.2, 34.8, 34.6, 34.5, 33.4, 30.5, 29.8, 23.4, 22.9, 14.0; IR (neat) 3268, 1668, 1634, 1456, 1373; HRMS (Qtof) calcd for C15H28N3 (MH+) 250.2283, found 250.2281. Attempted purification by chromatography on silica gel gave even less pure 41.

(±)-3aS,5aS,7S,8bR)-8-Butyl-1,3a,4,5,5a,6,7,8b-octahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-2-amine (Ptilocaulin, 1) and (±)-3aS,5aS,8aS,8bR)-8-Butyl-1,3a,4,5,5a,6,8a,8b-octahydro-7-methylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-2-amine (Isoptilocaulin, 4)

A 0.36 M solution of guanidine in MeOH was prepared by adding guanidinium hydrochloride (170 mg, 1.8 mmol) to a solution of NaOMe in MeOH prepared by adding Na (42 mg, 1.8 mmol) to anhydrous MeOH (5.0 mL) under nitrogen.

Guanidine in MeOH (0.36 M, 0.84 mL, 0.30 mmol) was transferred to a resealable tube containing indenone 60 (35 mg, 0.17 mmol) in 2.5 mL methanol under nitrogen. The tube was sealed and heated in an 85 °C oil bath for 24 h. The mixture was cooled, treated with water (1 mL) and NaBH4 (13 mg, 0.34 mmol), stirred overnight at 25 °C, quenched with 1% HNO3 (2.5 mL, 0.28 mmol) and diluted with CHCl3 (30 mL). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to yield 50 mg of crude 1 and 4 as a brown oil. Flash chromatography on silica gel (18:1 CHCl3/MeOH) gave 20.6 mg (39%) of an inseparable mixture of 1 (∼30%), 4 (∼30%) and numerous other isomers.

Data for ptilocaulin (1) were determined from the mixture : 1H NMR (CDCl3) 8.97 (br s, 1), 8.35 (br s, 1), 7.44 (br s, 2), 3.80-3.68 (m, 1), 2.52-1.81 (m, 6), 1.81-1.52 (m, 2), 1.52-1.18 (m, 7), 1.04 (d, 3, J = 6.8), 0.89 (m, 3); (CD3OD) 3.84 (br d, 1, J = 10), 2.58-2.33 (m, 3), 2.33-2.05 (m, 3), 1.89-1.56 (m, 2), 1.56-1.21 (m, 7), 1.09 (d, 3, J = 6.8), 0.94 (t, 3, J = 7.2); 13C NMR (CDCl3) 151.7, 126.9, 121.0, 53.2, 36.5, 33.9, 32.2, 31.5, 29.7, 29.6, 27.7, 24.6, 22.4, 19.5, 14.0; (CD3OD) 152.9, 128.1, 122.9, 51.3, 37.8, 35.5, 34.2, 33.3, 30.9, 29.2, 28.1, 25.6, 23.7, 20.1, 14.5. The 1H NMR (CDCl3 and CD3OD) data and 13C NMR (CDCl3 and CD3OD) correspond to the literature data,1,10 except that our 1H NMR (CDCl3 and CD3OD) data are 0.01 to 0.04 ppm downfield, our 13C NMR (CDCl3) data are 0.1 to 0.4 ppm upfield, and our 13C NMR (CD3OD) data are all about 0.1 to 0.3 ppm shifted.

Data for isoptilocaulin (4) were determined from the mixture: 1H NMR (CDCl3) 7.73 (br s, 1), 7.33 (br s, 1), 7.09 (br s, 2), 3.96 (d, 1, J = 4.8), 3.90-3.80 (m, 1), 2.52-1.81 (m, 7), 1.81-1.52 (m, 1), 1.74 (s, 3), 1.52-1.18 (m, 6), 0.91 (m, 3); (CD3OD) 4.02 (br d, 1, J = 4.8), 3.93-3.84 (m, 1), 2.58-2.33 (m, 1), 2.33-2.05 (m, 4), 2.05-1.88 (m, 2), 1.89-1.56 (m, 1), 1.78 (s, 3), 1.56-1.21 (m, 6), 0.95 (t, 3, J = 7.2); 13C NMR (CD3OD) 156.5, 136.4, 133.1, 54.6, 50.8, 41.0, 37.6, 37.2, 35.5, 32.9, 31.9, 31.8, 23.9, 19.9, 14.4; IR (neat); HRMS (EI, from mixture) calcd for C15H25N3 (M+) 247.2048, found 247.2049. The 1H NMR (CDCl3 and CD3OD) data and 13C NMR (CD3OD) correspond to the literature data,1,2c except that our 1H NMR (CD3OD) data are 0.04 to 0.05 ppm downfield and our 13C NMR (CD3OD) data are 0.1 to 0.2 ppm downfield.

Partial data for minor isomers: 1H NMR (CDCl3) 3.76-3.64 (m, 1), 3.53 (br d, 1, J = 4.4), 1.15 (d, 3, J = 7.2), 0.97 (d, 3, J = 7.2); (CD3OD) 3.77 (d, 1, J = 5.6), 3,59 (br d, 1, J = 4.8), 1.19 (d, 3, J= 7.2), 1.06 (d, 3, J = 6.8), 1.03 (d, 3, J = 6.8).

(3aS,5aS,7R,8S)-8-Butyl-1,3a,4,5,5a,6,7,8-octahydro-7-propylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-2-amine (Netamine E, 65)

A 0.22 M solution of guanidine in MeOH was prepared by adding guanidinium hydrochloride (104 mg, 1.1 mmol) to a solution of NaOMe in MeOH prepared by adding Na (25 mg, 1.1 mmol) to anhydrous MeOH (5.0 mL) under nitrogen.

Guanidine in MeOH (0.22 M, 2.0 mL, 0.44 mmol) was transferred to a resealable tube containing the 8:4:2:1 mixture of indenone 64 and stereoisomers (58 mg, 0.25 mmol) in 3.0 mL of MeOH under nitrogen. The tube was sealed and heated in an 85 °C oil bath for 24 h. The mixture was cooled, quenched with 1% HNO3 (5.0 mL, 0.55 mmol) and diluted with CHCl3 (30 mL). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to yield 82 mg of crude 65 as a yellow oil. Repeated flash chromatography on silica gel (25:1 CHCl3/MeOH) gave 31.5 mg (37.5%) of 90% pure 65 as a yellow oil: [α]D25 + 15.6 (c 0.09, CH2Cl2); [lit.8 [α]D21 + 35.0 (c 0.80, CH2Cl2)]; 1H NMR (CDCl3) 8.85 (br s, 1), 8.26 (br s, 1), 7.63 (br s, 2), 4.26 (br t, 1, J = 6.8), 2.51-2.21 (m, 1), 2.14 (br dd, 1, J = 13.6, 6.8), 2.10-2.00 (m, 1), 2.00-1.87 (m, 2), 1.77-1.03 (m, 13), 0.90 (t, 3, J = 6.8), 0.89 (t, 3, J = 6.8), 0.72 (ddd, 1, J = 11.2, 11.2, 11.2); (CD3OD) 4.27 (br t, 1, J = 6.8), 2.46-2.34 (m, 1), 2.19 (br dd, 1, J = 12.8, 6.8), 2.16-2.05 (m, 1), 2.05-1.80 (m, 2), 1.78-1.10 (m, 13), 0.94 (t, 3, J = 7.2), 0.93 (t, 3, J = 7.2), 0.77 (ddd, 1, J = 12, 12, 12); 13C NMR (CD3OD) 128.8, 119.8, 54.1, 42.3, 38.4, 37.7, 37.3, 36.5, 34.0, 30.4, 28.7, 27.5, 24.4, 21.4, 14.8, 14.6 (the peak at 155 was not observed); IR (neat) 3205, 1674; HRMS (EI) calcd for C17H29N3 (M+) 275.2361, found 275.2363.

A 1D NOESY experiment with irradiation of H-6α at δ 0.77 showed NOE enhancements of H-6β at δ 2.15 (very strong), H-5α at δ 1.30 (strong), H-8 at δ 1.95 (medium strong), H-1″ at δ 1.60 and δ 1.20 (medium strong), and H-5a at δ 2.43 (weak).

The 1H NMR (CD3OD) and 13C NMR (CD3OD) data correspond to the literature data,8 except that our 1H NMR (CD3OD) data are 0.01 to 0.03 ppm upfield and our 13C NMR (CD3OD) data are all about 0.1 to 0.4 ppm upfield.

(5aS,7R,8S)-8-Butyl-4,5,5a,6,7,8-hexahydro-7-propylcyclopenta[de]quinazolin-2-amine (Netamine G, 66)

Crude 65, containing isomers, (105 mg) was prepared as described above from indenone 64 (63 mg, 0.27 mmol). CH2Cl2 (6 mL) and activated MnO2 (103 mg, 1.2 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred in a sealed tube in a 55°C oil bath for 48 h. The mixture was cooled, filtered through Celite. The residue was washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with 10% K2CO3 solution (10 mL), dried over MgSO4 and concentrated to yield 45 mg of crude 66 as a yellow oil. Flash chromatography on silica gel (70:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH) gave 22.5 mg (25%) of 66 as a yellow oil: [α]D25 + 26.3 (c 0.255, CH2Cl2); [lit.8 [α]D21 + 27.0 (c 0.20, CH2Cl2)]; 1H NMR (CDCl3 9% protonated by TFA) 5.19 (br s, 2), 3.00-2.80 (m, 2), 2.60 (br dd, 1, J = 16.4, 8.4), 2.38 (ddd, 1, J = 12.0, 7.2, 7.2), 2.30 (ddd, 1, J = 8.8, 4.4, 4.4, H-8), 2.17 (ddd, 1, J = 12.4, 3.8, 3.8), 2.09-1.91 (m, 1), 1.83-1.64 (m, 2), 1.64-1.41 (m, 3), 1.41-1.15 (m, 5), 1.15-1.02 (m, 1), 0.93 (t, 3, J = 6.8), 0.87 (t, 3, J = 6.8), 0.78 (ddd, 1, J = 11.6, 11.6, 11.6); 13C NMR (CDCl3 9% protonated by TFA) 174.5, 166.4, 163.1, 126.3, 45.2, 38.8, 37.5, 37.1, 36.2, 33.6, 33.0, 31.0, 27.7, 23.2, 20.2, 14.4, 14.0; IR (neat) 3334, 3193, 1588; HRMS (EI) calcd for C17H27N3 (M+) 273.2205, found 273.2203.

The 1H NMR data and 13C NMR correspond to the literature data,8,44 except that our 1H NMR data are 0.02 to 0.05 ppm upfield and our 13C NMR data are all about 0.1 to 0.5 ppm shifted, possibly because of a slightly different extent of protonation.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details for the preparation of indenones 25, 60, and 64, tables comparing the spectral data of various synthetic and natural products, and 1H and 13C NMR spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (GM-50151) for support of this work. The 800 MHz spectrometer in the Landsman Research Facility, Brandeis University was purchased under NIH RR High-End Instrumentation program, 1S10RR017269-01. We thank Dr. Alan J. Freyer, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, for a copy of the 1H NMR spectrum of 5. We thank Prof. Hans-Guenther Schmalz, University of Cologne, for a copy of the NMR spectrum of the mixture of 1 and 23. We thank Prof. Mark T. Hamann, University of Mississippi, for copies of the 1H NMR spectra of 9 and the mixture of 13 and 14, a sample of the mixture of 13 and 14, and for determining the [α]D of mirabilin B. We thank Prof. Yoel Kashman, Tel-Aviv University, for helpful discussions, copies of the proton spectra of netamine G, and samples of netamines A and F.

References

- 1.(a) Harbour GC, Tymiak AA, Rinehart KL, Jr, Shaw PD, Hughes RG, Jr, Mizsak SA, Coats JH, Zurenko GE, Li LH, Kuentzel SL. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:5604–5606. [Google Scholar]; (b) Harbour GC. Ph D Dissertation. University of Illinois; Urbana, IL: 1983. The isolation and structure determination of antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and antiviral marine natural products. [Google Scholar]; Diss Abstr Int B. 1984;44(7):2159. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Patil AD, Kumar NV, Kokke WC, Bean MF, Freyer AJ, De Brosse C, Mai S, Truneh A, Faulkner DJ, Carte B, Breen AL, Hertzberg RL, Johnson RK, Westley JW, Potts BCM. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1182–1188. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gallimore WA, Kelly M, Scheuer PJ. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1420–1423. doi: 10.1021/np050149u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kossuga MH, de Lira SP, Nascimento AM, Gambardella MTP, Berlinck RGS, Torres YR, Nascimento GGF, Pimenta EF, Silva M, Thiemann OH, Oliva G, Tempone AG, Melhem MSC, de Souza AO, Galetti FCS, Silva CL, Cavalcanti B, Pessoa CO, Moraes MO, Hadju E, Peixinho S, Rocha RM. Quim Nova. 2007;30:1194–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavares R, Daloze D, Braekman JC, Hajdu E, Van Soest RWM. J Nat Prod. 1995;58:1139–1142. doi: 10.1021/np990403g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrow RA, Murray LM, Lim TK, Capon RJ. Aust J Chem. 1996;49:767–773. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil AD, Freyer AJ, Offen P, Bean MF, Johnson RK. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:704–707. doi: 10.1021/np960652u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capon RJ, Miller M, Rooney F. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:643–644. doi: 10.1021/np000564g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hua Hm, Peng J, Fronczek FR, Kelly M, Hamann MT. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:6461–6464. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorek H, Rudi A, Gueta S, Reyes F, Martin MJ, Aknin M, Gaydou E, Vacelet J, Kashman Y. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8838–8843. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruben RL, Snider BB, Hobbs FW, Jr, Confalone PN, Dusak BA. Invest New Drugs. 1989;7:147–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00170851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Snider BB, Faith WC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:861–864. [Google Scholar]; (b) Snider BB, Faith WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1443–1445. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Roush WR, Walts AE. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:721–723. [Google Scholar]; (b) Walts AE, Roush WR. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:3463–3478. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Uyehara T, Furuta T, Kabasawa Y, Yamada Ji, Kato T. Chem Commun. 1986:539–540. [Google Scholar]; (b) Uyehara T, Furuta T, Kabawawa Y, Yamada Ji, Kato T, Yamamoto Y. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3669–3673. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassner A, Murthy KSK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:1407–1410. [Google Scholar]; (b) Murthy KSK, Hassner A. Isr J Chem. 1991;31:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asaoka M, Sakurai M, Takei H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4759–4760. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cossy J, BouzBouz S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:5091–5094. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Schmalz HG, Schellhaas K. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1996;35:2146–2148. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schellhaas K, Schmalz HG, Bats JW. Chem—Eur J. 1998;4:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.PCModel (version 8.0) Serena Software; Bloomington, IN: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kula J, Sadowska H. Perfum Flavor. 1993;18:23–25. [Google Scholar]; Chem Abstr. 1994;120:6947. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong BD, Ji YI, Oh SS, Yang JD, Baik W, Koo S. J Org Chem. 1997;62:9323–9325. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Oikawa Y, Sugano K, Yonemitsu O. J Org Chem. 1978;43:2807–2808. [Google Scholar]; (b) Murakami M, Kobayashi K, Hirai K. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48:1567–1569. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The yield of 37 was lower and starting enone 36 (10%) was recovered if MeLi was used without CeCl3: Imamoto T, Takiyama N, Nakamura K, Hatajima T, Kamiya Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:4392–4398.

- 22.Dauben WG, Michno DM. J Org Chem. 1977;42:682–685. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) House HO, Giese RW, Kronberger K, Kaplan JP, Simeone JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;72:2800–2810. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pradhan SK. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:6351–6358. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Bal SA, Marfat A, Helquist P. J Org Chem. 1982;47:5045–5050. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johansson M, Sterner O. Org Lett. 2001;3:2843–2845. doi: 10.1021/ol016286+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsantali GG, Takakis IM. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6455–6458. doi: 10.1021/jo034350q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.For the reaction of guanidines with enones in EtOH and t-BuOH see: Kim YH, Yoon CM, Lee NJ. Heterocycles. 1981;16:49–52.El-Rayyes NR, Ramadan HM. J Heterocycl Chem. 1987;24:1141–1147.

- 26.We thank Dr. Alan J. Freyer, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals for a copy of the 1H NMR spectrum of 5.

- 27.This proton was reported to absorb as a dt, J = 11.6, 5.3 Hz. It actually absorbs as a dt, J = 5.3, 11.6 Hz. Prof. Hans-Guenther Schmalz, University of Cologne, personal communication, January 8, 2008. We thank Prof Schmalz for a copy of the 1H NMR spectra of the mixture of 1 and 23.

- 28.Vanden Eynde JJ, Audiart N, Canonne V, Michel S, Van Haverbeke Y, Kappe CO. Heterocycles. 1997;45:1967–1978. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Deli J, Lóránd T, Szabó D, Földesi A, Zschunke A. Coll Czech Chem Commun. 1985;50:1602–1610. [Google Scholar]; (b) Thyagarajan BS. Chem Rev. 1958;58:439–460. [Google Scholar]

- 30.We thank Prof. Mark T. Hamann, University of Mississippi for a sample of the mixture of 13 and 14 and a copy of the 1H NMR spectrum of the mixture of 13 and 14.

- 31.(a) Brown DS, Marples BA, Muxworthy JP, Baggaley KH. J Chem Res (S) 1992:28–29. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bovicelli P, Lupattelli P, Mincione E, Prencipe T, Curci R. J Org Chem. 1992;57:2182–2184. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buscemi S, Pace A, Piccionello AP, Vivona N, Pani M. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:1158–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlone A, Marigo M, North C, Landa A, Jørgensen KA. Chem Commun. 2006:4928–4930. doi: 10.1039/b611366d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoye TR, Jeffrey CS, Shao F. Nat Prot. 2007;2:2451–2458. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yasuhara F, Yamaguchi S, Takeda M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1991;64:3390–3394. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Professor Mark Hamann, University of Mississippi, personal communication, April 28 and 29. 2008.

- 36.Brown PM, Käppel N, Murphy PJ, Coles SJ, Hursthouse MB. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:1100–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Urones JG, Garrido NM, Díez D, El Hammoumi MM, Dominguez SH, Casaseca JA, Davies SG, Smith AD. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:364–372. doi: 10.1039/b313386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thalji RK, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16778–16779. doi: 10.1021/ja054085l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hua HM, Peng J, Dunbar DC, Schinazi RF, de Castro Andrews AG, Cuevas C, Garcia-Fernandez LF, Kelly M, Hamann MT. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:11179–11188. For reviews of these alkaloids see: Berlinck RGS, Burtoloso ACB, Kossuga MH. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:919–954. doi: 10.1039/b507874c.Berlinck RGS, Kossuga MH. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:516–550. doi: 10.1039/b209227c. and previous reviews in this series.

- 40.(a) Black GP, Murphy PJ, Thornhill AJ, Walshe NDA, Zanetti C. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:6547–6554. [Google Scholar]; (b) Snider BB, Busuyek MV. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1707–1711. doi: 10.1021/np990312j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slomp G, Jr, Johnson JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:915–921. [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Ito H, Ishizuka T, Arimoto K, Miura K, Hosomi A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:8887–8890. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lipshutz BH, Keith J, Papa P, Vivian R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:4627–4630. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jurkauskas V, Sadighi JP, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2003;5:2417–2420. doi: 10.1021/ol034560p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Deutsch C, Krause N, Lipshutz BH. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2916–2927. doi: 10.1021/cr0684321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riand J, Chenon MTh, Lumbroso-Bader N. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:6838–6845. [Google Scholar]

- 44.We thank Prof. Yoel Kashman, Tel-Aviv University, for helpful discussions, copies of the proton spectra of netamine G, and samples of netamines A and F.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details for the preparation of indenones 25, 60, and 64, tables comparing the spectral data of various synthetic and natural products, and 1H and 13C NMR spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.