Abstract

Aims

To determine how genetic and environmental contributions affecting the number of psychoactive substances used varies with age and gender over the course of adolescence

Design

Estimates of genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental contributions to total variance in diversity of substances used at ages 11, 14 , and 17 were obtained by fitting a multivariate behavior genetic (Cholesky) model.

Participants

711 male and 675 female twins.

Measurements

Participants reported whether they had used each of 11 substances.

Findings

The average diversity of substances used increased over time for both males and females, and males generally reported a wider diversity of substances used than females. Influences of genetic factors increased with age and were greater for males than for females at ages 14 and 17. Genetic factors remained consistent (i.e. highly correlated) across ages for both males and females, as did shared environmental influences for males. Non-shared environmental factors for both sexes and females’ shared environmental factors were age-specific.

Conclusions

Regardless of sex, the proportion of variance in substances used attributable to genetic factors increases during adolescence, although it is greater for males than females at later ages. These findings indicate that prevention interventions may be most effective if they target early adolescence when environmental factors account for the majority of variance in substance use. The high correlation of genetic factors across ages suggests that early use may sometimes signal an early expression of a developmentally stable genetic predisposition.

Keywords: substance use, behavior genetics, twin study, longitudinal, sex differences

Introduction

Numerous studies consistently report that the diversity of substances used increases throughout high school and is generally greater for males than for females (e.g., 1–3). Breaking down the relative impact of genetic and environmental factors by age and sex may allow us to better understand the potentially complex etiology of substance use during this developmental period. In particular, a twin study design provides a means to estimate the extent to which environmental and genetic predispositions influence substance use behavior. Furthermore, a longitudinal study design provides the unique ability to separate developmental effects from secular trends in substance use. Although most previous studies have investigated genetic and environmental effects on substance use collapsing across age and/or sex (e.g., 4–8), it is likely that both play a role in determining the specific etiologic vulnerabilities to substance use across adolescent development, as this is a period of substantial change in substance related behavior.

The majority of studies investigating relative genetic and environmental effects on substance use utilize adult twin samples with broad age ranges (e.g., 4–6, 9–12). Studies of adult samples that focus on use, rather than or in addition to misuse, generate significant estimates of shared environmental influence, or those common factors that have the same effects on both twins (5), accounting for around one-quarter of the population variance. Moreover, genetic factors, which are either fully or half shared between twins, and non-shared environmental factors, those experiences which are unique to each twin (5), are generally estimated to be even more influential, each accounting for one-third to one-half of the variance in substance use (e.g., 5, 10–12). These findings are interesting in that they document both significant genetic and shared environmental components to variance in substance use, although they do not speak to the developmental trajectory which leads up to observed patterns in adult substance use.

Studies of adolescent substance use initiation generate varying accounts of genetic and environmental influences, with estimates generally ranging between one-quarter to one-half of the variance for each of the factors (genetic, shared and non-shared environmental) (e.g., 7, 8, 13, 14). A study of the longitudinal implications of earlier substance use indicated that the risk of substance abuse or dependence within seven years of first drug use markedly increases as the age of first use decreases, indicating a meaningful and troubling connection between early pre-adolescent or adolescent drug experimentation and negative adult substance use outcomes (15). This relationship is likely fueled by etiologic changes in substance use during adolescence.

Although studies consistently document increasing genetic influence during adolescence on a variety of phenotypes, including substance-specific use such as drinking behavior, this pattern has yet to be documented in the context of diversity of substances used (16, 17). When estimating the relative impact of genetic and environmental influences on substance use behaviors, those few studies that do focus on adolescents either collapse across age ranges (e.g., 7, 8) or use narrow age bands (e.g. 13, 14). This results in a lack of information on how relative genetic and environmental influences may change during adolescence.

Regarding sex differences in substance use, males tend to use more substances than females (e.g., 1–3). Estimates of genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in substance use appear to differ by sex in mixed-age samples. In adolescent samples, genetic factors tend to account for a greater proportion of the variance in males (around one-third) than in females (around one-quarter), although these differences do not always end up being statistically significant (e.g., 8, 13).

In sum, although many studies estimate the relative genetic and environmental effects on substance use, the majority of them collapse across broad age bands, and many also collapse across sex. This leads to a loss of information on the potential longitudinal changes and gender differences that may be important during the key developmental period of adolescence. Overall, previous studies indicate that genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental factors appear to account for approximately equivalent proportions of the variance in adolescent substance use. The current study sought to expand upon previous research by investigating the possible developmental trends in relative genetic and environmental influences on the diversity of substances used during adolescence, as well as examining the role of gender. Specifically, we examined the etiology of diversity of substances used in 1386 male and female twins studied when they were 11, 14, and 17 years old. Diversity of substances used provides an important index of substance use severity (18). It also serves as a measure of substance involvement applicable across adolescence – diversity of substances used has the same meaning at all three ages of assessment. This measure is applicable even in the youngest age group because easily accessible substances like tobacco are included. Similarly, because less socially acceptable substances (i.e. amphetamines) are also included, diversity of substances endorsed retains variance in the oldest age group. By utilizing a longitudinal design and a measure with equivalent interpretability throughout adolescence, any detected age effects can be interpreted as true developmental trends.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of twin pairs born in Minnesota who participated in the longitudinal Minnesota Twin and Family Study (MTFS). Participants were initially identified through birth records from 1977 to 1982 for males and 1981 to 1985 for females. Families were contacted via telephone and invited to begin their participation when the twins were approximately 11-years-old. Of the study-eligible twin pairs (living within one day’s drive from Minneapolis, MN and without physical or mental handicap which would interfere with assessment) identified from birth records, 90% were able to be located and fewer than 20% declined participation. Overall, 376 male and 380 female twin pairs participated at intake, at which point project staff obtained written informed consent. Zygosity was initially assessed by a questionnaire filled out by the twins’ parents; trained project staff diagnosis based on physical similarity; and ponderal index, cephalic index, and fingerprint ridge count. If there was any discrepancy among these three methods, zygosity was determined by evaluating 12 blood group antigens from blood samples. In confirmatory analysis of 50 twin pairs, project staff and physical similarity diagnoses were always in agreement with serological analysis. All twins provided written informed assent to participate, with one of their parents providing written informed consent as well.

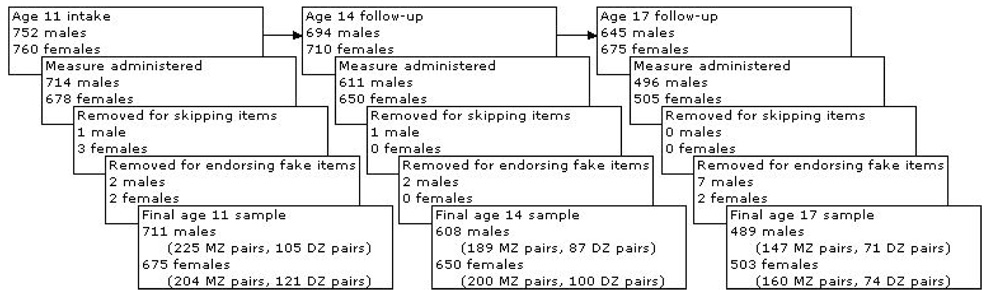

The final sample included 225 MZ male, 204 MZ female, 105 DZ male, and 121 DZ female twin pairs at intake. At the first follow-up, 189 MZ male, 200 MZ female, 87 DZ male, and 100 DZ female twin pairs were included (88% of the original individuals providing data) and there were 147 MZ male, 160 MZ female, 71 DZ male, and 74 DZ female twin pairs at the second follow-up (69% providing data). Because inclusion in the present sample required an in-person assessment to establish the substance use phenotype and up to approximately 20% of MTFS participants complete their follow-up assessment by telephone, participation rates in the current study are lower than those reported in other MTFS studies (greater than 90%) (19). Additionally, participants who either skipped items or endorsed fake items (“bleomycins” and “cadrines”) were excluded from analysis (see Figure 1). Twins in the final sample are identified by the target age for their intended assessment: 11-year-olds (M=11.70, SD=0.43) at intake, 14-year-olds (M=14.77, SD=0.51) at the first follow-up, and 17-year-olds (M=17.99, SD=0.60) at the second follow-up. Because some individuals participated after their targeted assessment year, and this became more likely with each follow-up, actual ages at participation were somewhat higher than the target age. For convenience and to maintain consistency with previous reports, we refer to each assessment by the targeted age.

Figure 1.

Steps (and subsequent ns) for participant inclusion in final data analyses at each time-point.

Attrition

Attrition effects in the current study were examined using the software program Mplus (20) by regressing substance use counts on whether or not individuals had returned for later assessments (coded dichotomously as 0/1, with 1 indicating attrition from later evaluations) to examine differences between those who did and did not complete the measure at a follow-up time-point. Performing this evaluation as a regression in Mplus allowed us to control for the non-independent nature of twin data. There was no significant difference in 11-year-old substance use counts between participants who did and did not complete the 14-year-old assessment (rmales=0.15, z=1.67, p=0.09; rfemales=−0.01, z=−0.09, p=0.93) or between those 11-year-olds who did and did not complete the 17-year-old assessment (rmales=0.11, z=1.36, p=0.17; rfemales=−0.04, z=−1.00, p=0.32). There was a significant difference on 14-year-old counts in those who did and did not complete the 17-year-old follow-up (rmales=0.40, z=2.46, p=0.01; rfemales=0.41, z=2.035, p=0.04). However, the effect size, as indicated by Cohen’s d, was small (dmales=0.29, dfemales=0.26), with those who did not complete the 17-year-old assessment endorsing only slightly more substances at age 14 than those who did complete the later assessment (males: Mattrition=1.69, Mreturn=1.29; females: Mattrition=1.52, Mreturn=1.10). These statistics suggest that although attrition may at first glance appear notable, any existing differences are small and thus unlikely to impact the results presented here.

Measure

During day-long in-person assessments at 11-, 14-, and 17-year-old time-points, a computerized substance use questionnaire was individually self-administered to the twins, without the presence of project staff. At intake, the dependent variable of diversity of substances used was the lifetime count of the number of different substances used by age 11. At each follow-up, it was the substance use count since the previous assessment, measured as the total number of 11 substances the twin endorsed having ever used recreationally (e.g., to get high). Questions were phrased as, “Have you ever used [substance]?” The substances asked about were (with examples given in the questionnaire shown in parentheses): tobacco (cigarettes, cigars, chewing tobacco), alcohol, marijuana/hashish, stimulants (uppers, speed, diet pills), tranquilizers (Valium, Librium, etc.), Quaaludes/downers, inhalants (gasoline, glue, aerosol sprays, peppers, rush, locker rooms), over the counter medications (NoDoz, Sominex, cold capsules, etc.), cocaine (coke, crack), PCP (angel dust, peace pills)/LSD (acid)/other psychedelics, and heroin (horse, smack)/opiates (methadone, opium, morphine, codeine, etc.). For tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, response options were: “I have never tried [substance]”, “I have never tried [substance] but might sometime”, “I have tried [substance] but have not used it in the past 12 months”, “I have tried [substance] but have used it only once in a while in the past 12 months”, and “I have tried [substance] and have used it a lot in the past 12 months.” For all other substances, response options were: “Yes in the last 12 months”, “Yes but not in the last 12 months”, and “No.” Responses indicating ever use were converted to dichotomous yes/no values for analysis to maintain conformity across substances.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of descriptive statistics were conducted in the computer program Mplus (20). Age and sex differences in diversity of substances used were examined to confirm that the measure being used behaved in a manner consistent with findings from previous research (e.g. 1–3). Main effects of age and sex on substance use diversity were examined while correcting for the non-independent nature of the twin pair observations using the robust maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus. All tests for age and sex differences were two-tailed. Twin data were analyzed to estimate genetic and environmental influences via the computer program Mx (21) using a multivariate Cholesky model. Phenotypic variance was decomposed into three components: variance due to additive genetic factors (a2); variance due to shared environmental, or family-level, factors (c2); and variance due to non-shared environmental, or individual-specific, factors (e2). Calculation of variance accounted for by each of these factors is performed by comparing within-pair monozygotic twin correlations to within-pair dizygotic twin correlations. Additive genetic effects are indicated when rMZ>rDZ, shared environmental effects when rDZ>0.5rMZ, and non-shared environmental effects when rMZ<1.0. The primary model calculated variance components separately by sex at each age. Additional models were calculated to evaluate goodness of fit in which estimates of the variance components were constrained to be equal across age, sex, or both. Estimates were obtained from observed twin data using a maximum likelihood estimator in the software program Mx. Model fit was evaluated using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), with a lower AIC indicating a better fitting model. Missing data were handled by reading raw data into Mx, and fitting to the observed and unobserved data vectors using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML).

Results

Sex differences in substance use counts

Proportions of participants who reported ever using each substance are reported in Table 1, along with mean counts for males and females at 11-, 14-, and 17-years-old. (While the 17-year-old assessment in fact included individuals over the age of 18, and therefore able to legally use tobacco products, there was not a significant difference between those who were 17-years-old and those who were over the age of 17 on tobacco use endorsement rates, 62% and 67% respectively, z=1.65, p=0.10.) Whether or not males differed from females in the diversity of substances used was investigated by regressing substance use counts at each age on sex (coded dichotomously as 0/1 for females and males, respectively, as well as taking into account the clustered nature of twin data). Males reported higher total substance use counts than females at all three ages (11 years: Mmale=0.52, Mfemale=0.21, r=−0.31, z=−7.88, p<0.0001; 14 years: Mmale=1.39, Mfemale=1.21, r=−0.19, z=−1.84, p=0.066; 17 years: Mmale=1.98, Mfemale=1.61, r=−0.47, z=−3.29, p=0.001), although the difference was not quite significant at 14 years. Variance in diversity of substances used remained similar between males and females across ages.

Table 1.

Proportion of Participants who Endorsed Ever Using Each Substance and Descriptive Statistics of Diversity of Substances Used, Broken Down by Age and Sex

| Age 11 | Age 14 | Age 17 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| n | 711 | 675 | 608 | 650 | 489 | 503 |

| Substance | ||||||

| Tobacco | 6% | 2% | 43% | 30% | 72% | 57% |

| Alcohol | 17% | 6% | 51% | 42% | 76% | 73% |

| Marijuana | 1% | 0% | 18% | 11% | 43% | 34% |

| Stimulants | 0% | 0% | 4% | 5% | 10% | 6% |

| Tranquilizers | 1% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 2% |

| Downers | 0% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 3% | 0% |

| Inhalants | 7% | 3% | 5% | 4% | 5% | 2% |

| OTC Meds | 21% | 11% | 28% | 26% | 30% | 32% |

| Cocaine | 0% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 10% | 3% |

| Psychedelics | 0% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 13% | 3% |

| Opiates | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 6% | 3% |

| Total Count | ||||||

| Mean | 0.52 | 0.21* | 1.39 | 1.21 | 2.42 | 2.13* |

| Std. Dev. | 0.79 | 0.48 | 1.35 | 1.51 | 1.88 | 1.61 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| IQR | 0 – 1 | 0 – 0 | 0 – 2 | 0 – 2 | 1 – 3 | 1 – 3 |

| Range | 0 – 4 | 0 – 3 | 0 – 9 | 0 – 10 | 0 – 11 | 0 – 10 |

OTC = over-the-counter medications, IQR = interquartile range

differs significantly from same-age males, p<0.01

mean substance counts increase with age, p<0.001 for both males and females

Age effects on substance use counts

Whether or not diversity of substances used increased over time was evaluated in Mplus using a Poisson-distributed linear growth model, with time points at 11, 14, and 17 years of age represented by 0, 1, and 2, respectively. The model indicated that there was an increase in substance use counts during adolescence for both males (slope=0.85) and females (slope=1.07) with a greater overall rate of growth for females than for males (z=3.53, p<0.001). The model in which the slope of substance use counts over time was allowed to be non-zero (AICmales=3573.4, AICfemales=3306.7) fit significantly better than when the model assumed no change over time (i.e., with the slope set to zero, AICmales=3958.3, AICfemales=3734.4; χ2males(1)=193.4, χ2females(1)=214.8, p<0.0001 for both). This model showed that, as expected, the total diversity of substances used significantly increased between ages 11 and 17 for both males and females.

Relative genetic and environmental contributions

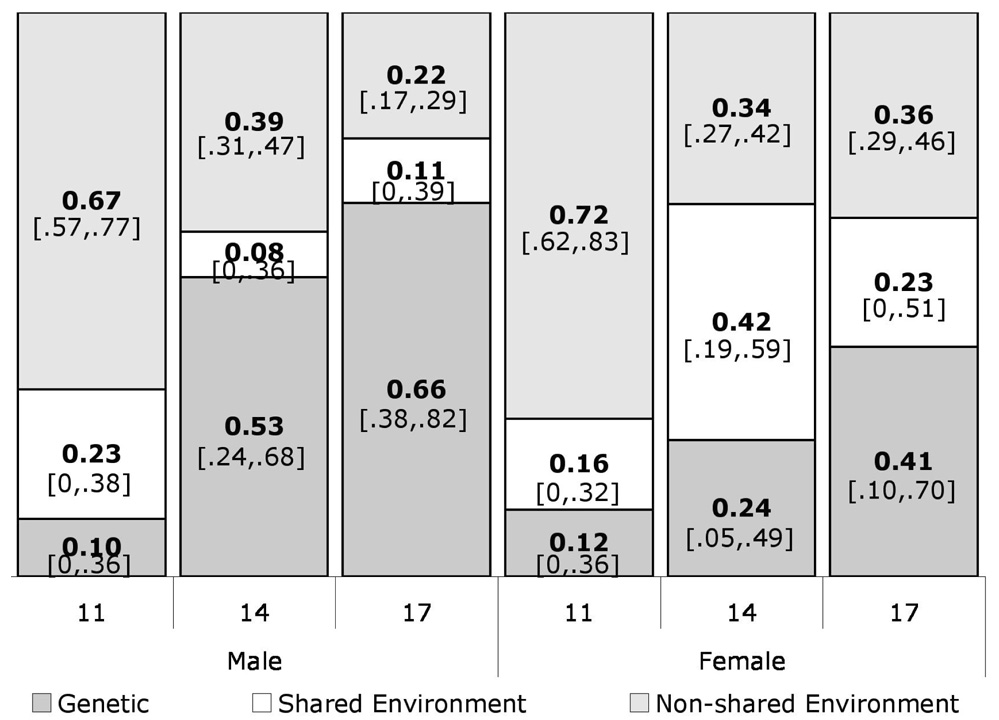

Estimates of genetic and environmental influences on diversity of substances used were computed in Mx using a multivariate Cholesky model. The model was fit to a log-transformed diversity of substances used [ln(substances+1)] due to the positively-skewed nature of the raw data. The overall model fit the transformed data significantly better than those models in which age, sex, or both were set as equal (p<0.0001 for all, compared on a chi-squared distribution, see Table 2). As shown in Figure 2, population variance attributable to additive genetic factors increased with age and generally had a greater effect on males than on females across the ages. Conversely, both shared and unique environmental effects decreased across age and were more influential in females than in males.

Table 2.

Questions and Answers About Goodness of Fit for Variance Component Models of Substance Use Counts

| Question | Answer | −2lnL | Δ-2lnL | Δdf | p | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How does the overall model fit? | 4003.1 | −2996.9 | ||||

| Can estimates be equated across ages? | No | 4943.2 | 940.1 | 30 | <.0001 | −2116.8 |

| Can estimates be equated across sexes? | No | 4109.6 | 106.4 | 18 | <.0001 | −2926.4 |

| Can estimates be equated across ages and sexes? | No | 4960.0 | 956.8 | 33 | <.0001 | −2106.0 |

−2lnL = −2 x natural-log-likelihood of the model; AIC = Akaike’s Information Criterion

Figure 2.

Proportion of population variance in substance use counts accounted for by each of the variance components, estimated separately by sex and age. Estimates of 95% confidence intervals are given in brackets.

Correlations for genetic and environmental effects between ages (see Table 3) were high for genetic influences in both males and females and for shared environmental effects in males. However, non-shared environmental effects for both males and females and shared environmental effects in females were not as highly correlated between ages. These results suggest that in males, specific genetic and shared environmental influences on substances used remains largely constant across ages, while the non-shared environmental influences are largely age specific. In females, however, only the genetic components remain the same across ages, while both shared and non-shared environmental factors seem to be due to age-specific influences.

Table 3.

Correlations Between Variance Components at Three Ages in the Saturated Model – Male Estimates are Given Below the Diagonal, Female Estimates are Shown Above, 95% Confidence Intervals are in Parentheses

| Additive genetic factors (a2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 14 | 17 | |

| 11 | -- |

1.00 (1.00,1.00) |

0.98 (0.98,0.98) |

| 14 |

0.90 (0.88,0.92) |

-- |

0.98 (0.98,0.98) |

| 17 |

0.49 (0.42,0.55) |

0.81 (0.78,0.84) |

-- |

| Shared environment (c2) | |||

| 11 | 14 | 17 | |

| 11 | -- |

0.11 (0.03,0.19) |

0.02 (−0.07,0.11) |

| 14 |

0.49 (0.43,0.55) |

-- |

0.52 (0.45,0.58) |

| 17 |

0.49 (0.42,0.55) |

1.00 (1.00,1.00) |

-- |

| Non-shared environment (e2) | |||

| 11 | 14 | 17 | |

| 11 | -- | 0.02 (−0.06,0.10) |

−0.15 (−0.06, −0.23) |

| 14 | 0.08 (0.00,0.16) |

-- |

0.29 (0.21,0.37) |

| 17 | 0.09 (0.00,0.18) |

0.21 (0.12,0.29) |

-- |

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies (e.g. 1–3), the diversity of substances used increased over the period of adolescence and males used a greater diversity of substances than females. However, the sex difference was not significant at age 14, potentially due to the later onset of puberty in males than in females (22), such that females begin to “catch-up” with their adult substance use levels earlier than males. Similar to a wide range of other phenotypes (16, 17), both males and females demonstrated a pattern of increasing genetic influence over time on diversity of substances used. The genetic effects at one age were highly correlated with genetic effects at other ages for both males and females, although their relative influence increased. Additionally, genetic factors impacted the diversity of substances used more in males than in females at age 14 and 17 and shared environmental factors exerted greater influence over females than males, again at ages 14 and 17. It is also interesting to note that the confidence intervals on the biometric estimates shown in Figure 2 suggest that 14-year-old females are the only group to display significant shared environmental effects. These differing proportions of variance attributable to genetic versus environmental factors may be explained by varying motivations for use. In females, substance use may be linked to a “self-medicating” orientation in reaction to greater rates of depressive symptoms, while in males substance use may be more part of a broad continuum of externalizing behaviors (23).

The longitudinal nature of the data, coupled with the notable sample size (N=1386) derived from a community (non-clinical) twin sample, allows for these unique estimates of developmental trends in adolescent substance use independent of cohort effects. However, it must be noted that these estimates refer to the total diversity of substances used and do not take into account frequency or severity of use. Both licit and illicit substances were included; although the measure as a whole is internally consistent (α=0.72), there were notable differences in the proportions associated with use of the individual substances, likely due at least in part to differences in availability of licit and illicit substances. (Though it is important to note that only over-the-counter medications and inhalants can be legally acquired by participants in this sample, those substances which are widely legally available for older persons – i.e. alcohol and tobacco – may be more readily available to underage users than those which are illegal for all.)

Although these findings highlight the relative differences in impact genetic, shared- and non-shared environmental factors have on the diversity of substances used between males and females and across ages, from these analyses we can not discern the identity of the environmental influences and genetic polymorphisms that account for these observed differences, nor how these genetic and environmental influences interact. Relationships between substance use and environmental factors such as deviant peers (e.g. 24–27), parental factors (e.g. 24–28), and socioregional location (e.g. 29, 30) have been documented and may moderate the longitudinal etiology of diversity of substances used.

Additionally, early substance use has been repeatedly linked to externalizing behaviors, such as police contact and sexual intercourse, as well as clinical diagnoses, such as conduct disorder, all of which occur with greater frequency in males (31–33). While this may help explain males consistently using a greater diversity of substances than females throughout adolescence, it does not necessarily account for the differing levels of genetic influence observed between the sexes across ages. While these specific genetic factors remain highly correlated across age, it is possible that these same factors overlap to some extent with risk for frequency of use and misuse (34). Despite environmental unknowns and possible externalizing covariates, earlier substance use may nevertheless signal an earlier display of a developmentally stable genetic predisposition, as the specific genetic factors remain stable across ages, rather than a unique etiology.

These findings indicate that intervention in substance use during early adolescence, when environmental factors are overwhelmingly more influential on the diversity of substances used, may be more effective than intervention in later adolescence, especially in males. The developmental process of increasing genetic influence is not unique to substance use (16, 17) and its consistency highlights the importance of affecting change by early adolescence while environmental effects still account for a majority of population variance in behavior. The sex differences in etiology suggest that interventions focusing on family-level factors may be more successful with females throughout adolescence, while early individual-level interventions with males would be key. As substance use has been repeatedly linked to a range of externalizing behaviors (e.g. 35, 36), this understanding of the growing effect of genetic factors on substance use may help inform treatments of the cluster of externalizing behaviors, which present a similar pattern of weak heritability early in adolescence, but increasing heritability later in adolescence (33). Earlier prevention and intervention techniques may be especially important, as earlier substance use has been linked with more negative abuse and dependence outcomes later in life (15).

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: United States Public Health Service Grants AA09367, DA05147

References

- 1.Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashdan TB, Vetter CJ, Collins RL. Substance use in young adults: associations with personality and gender. Addict Behav. 2004;30:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloor R. The influence of age and gender on drug use in the United Kingdom – a review. Am J Addict. 2006;15:201–207. doi: 10.1080/10550490600625269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grove WM, Eckert ED, Heston L, Bouchard TJ, Segal N, Lykken DT. Heritability of substance abuse and antisocial behavior: a study of monozygotic twins reared apart. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;27:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang KL, Livesley WJ, Vernon PA. Alcohol and drug problems: a multivariate behavioural genetic analysis of comorbidity. Addiction. 1995;90:1213–1221. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90912136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Bree MBM, Johnson EO, Neale MC, Pickens RW. Genetic and environmental influences on drug use and abuse/dependence in male and female twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;52:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maes HH, Woodard CE, Murrelle L, Meyer JM, Silberg JL, Hewitt JK, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and drug use in eight- to sixteen-year-old twins: the Virginia twin study of adolescent behavioral development. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:293–305. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhee SH, Hewitt JK, Young SE, Corley RP, Crowley TJ, Stallings MC. Genetic and environmental influences on substance initiation, use, and problem use in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1256–1264. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gynther LM, Carey G, Gottesman II, Vogler GP. A twin study of non-alcohol substance abuse. Psychiatry Res. 1995;56:213–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)02609-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Lin N, et al. Genetic influences on DSM-III-R drug abuse and dependence: a study of 3372 twin pairs. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:473–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960920)67:5<473::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Corey LA, Prescott CA, Neale MC. Genetics and environmental risk factors in the etiology of illicit drug initiation and subsequent problem use in women. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:351–356. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karkowski LM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Multivariate assessment of factors influencing illicit substance use in twins from female-female pairs. Am J Med Genet (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2000;96:665–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han C, McGue MK, Iacono WG. Lifetime tobacco, alcohol and other substance use in adolescent Minnesota twins: univariate and multivariate behavioral genetic analyses. Addiction. 1999;94:981–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGue M, Elkins I, Iacono WG. Genetic and environmental influences on adolescent substance use and abuse. Am J Med Genet (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2000;96:67–677. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001009)96:5<671::aid-ajmg14>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose RJ, Dick DM. Gene-environment interplay in adolescent drinking behavior. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004/2005;28:222–229. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergen SE, Gardner CO, Kendler KS. Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:423–433. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Martin C, Mezzich A, Brown S. Application of item response theory to quantify substance use disorder severity. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson W, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic and environmental influence on academic achievement trajectories during adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:513–532. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical Modeling. 6th ed. Richmond, Va: VCU Department of Psychiatry; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee PA, Guo SS, Kulin HE. Age of puberty: data from the United States of America. APMIS. 2001;109:81–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGue M, Pickens RW, Svikis DS. Sex and age effects on the inheritance of alcohol problems: a twin study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:3–17. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. Searching for interactive effects in the etiology of early-onset substance use. Behavior Genetics. 1999;29:433–444. doi: 10.1023/a:1021627021553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walden B, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt SA, Elkins I. Identifying shared environmental contributions to early substance use: the respective roles of peers and parents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:440–450. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walden B, Iacono WG, McGue M. Trajectories of change in adolescent substance use and symptomatology: impact of paternal and maternal substance use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:35–43. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dick DM, Pagan JL, Viken R, Purcell S, Kaprio J, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ. Changing environmental influences on substance use across development. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:315–326. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dick DM, Viken R, Purcell S, Kaprio J, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ. Parental monitoring moderates the importance of genetic and environmental influences on adolescent smoking. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:213–218. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dick DM, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Exploring gene-environment interactions: socioregional moderation of alcohol use. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:625–632. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legrand LN, Keyes M, McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger RF. Rural environments reduce the genetic influence on adolescent substance use and rule-breaking behavior. Psychological Medicine. 2007;38:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction or early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGue M, Iacono WG. The association of early adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1118–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger R. The association of early adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology: a multivariate behavioral genetic perspective. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:591–602. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heath AC, Martin NG, Lynskey MT, Todorov AA, Madden PAF. Estimating two-stage models for genetic influences on alcohol, tobacco or drug use initiation and dependence vulnerability in twin and family data. Twin Research. 2002;5:113–124. doi: 10.1375/1369052022983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: a longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]