Abstract

Computed tomography (CT) remains a critical diagnostic tool for evaluating patients with cerebrovascular disease, and the advent of specialized systems for imaging rodents has extended these techniques to small animal models of these diseases. We therefore have evaluated in vivo methods of imaging rat models of hemorrhagic stroke using a high resolution compact computed tomography (‘microCT’) system (FLEX(tm) X-O(tm), Gamma Medica-Ideas, Northridge, CA). For all in vivo studies, the head of the anesthetized rat was secured in a custom immobilization device for microCT imaging with 512 projections over 2 min at 60 kVp and 0.530 mA (Itube × t/rotation = 63.6 mAs). First, imaging without iodinated contrast was performed (a) to differentiate the effect of contrast agent in contrast-enhanced CT and (b) to examine the effectiveness of the immobilization device between two time points of CT acquisitions. Then, contrast-enhanced CT was performed with continuous administration of iopromide (300 mgI ml−1 at 1.2 ml min−1) to visualize aneurysms and other vascular formations in the carotid and cerebral arteries that may precede subarachnoid hemorrhage. The accuracy of registration between the noncontrast and contrast-enhanced CT images with the immobilization device was compared against the images aligned with normalized mutual information using FMRIB's linear image registration tool (FLIRT). Translations and rotations were examined between the FLIRT-aligned noncontrast CT image and the nonaligned noncontrast CT image. These two data sets demonstrated translational and rotational differences of less than 0.5 voxel (∼85 μm) and 0.5°, respectively. Noncontrast CT demonstrated a very small volume (0.1 ml) of femoral arterial blood introduced surgically into the rodent brain. Continuous administration of iopromide during the CT acquisition produced consistent vascular contrast in the reconstructed CT images. As a result, carotid arteries and major cerebral blood vessels were visible with contrast-enhanced CT, but not with noncontrast CT. In conclusion, the CT-compatible immobilization device was useful for in vivo microCT imaging of intracranial blood and of vascular structures within and immediately adjacent to the rodent brain. The microCT imaging technique is also compatible with continuous administration of a conventional iodinated contrast agent (e.g. iopromide) and therefore does not require specialized small animal specific contrast agent that has comparatively long in vivo residence time.

1. Introduction

In clinical settings, computed tomography (CT) is an important imaging modality for management of cerebrovascular disease (Ahmed and Masaryk 2004), and has an especially important role in managing patients with intracranial hemorrhage including hemorrhagic stroke. Contrast-enhanced CT is also clinically useful for delineating vascular morphology and pathology including aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations, and provides insights concerning the etiology of hemorrhagic stroke including detection of aneurysm and rupture in cerebral arteries (Joo et al 2006). There are on-going efforts to develop effective therapeutic methods to prevent hemorrhagic stroke or its secondary injury (Belayev et al 2005, MacLellan et al 2004, Xue and Del Bigio 2000). The advent of small animal models of cerebrovascular disease therefore has stimulated an urgent need to develop a reliable noninvasive imaging technique that longitudinally and noninvasively follows effects of experimental treatments in small animals.

High resolution in vivo compact computed tomography (microCT) systems have become increasingly important for examining morphology in small animal models of human biology and disease (Kennel et al 2000, Paulus et al 2000). For a specific biological study using in vivo microCT, careful evaluations of CT imaging techniques must precede their application for visualizing aneurysms in rodent models and in other biological studies. Unlike in vitro or ex vivo microCT which provides very fine spatial resolution (typically less than 10 μm), the spatial resolution of in vivo microCT studies suffers from physiologic (e.g., cardiac, respiratory) motion, realistic acquisition time during which the animal can be maintained on anesthesia, and the amount of x-ray dose and iodinated contrast media deliverable to an individual animal within the context of an imaging study often performed with sequential scans (De Clerck et al 2004). Of these issues, image blurring due to physiologic motion can be difficult to control. For our study, we therefore developed a microCT-compatible stereotactic device for immobilizing the head of the rat during the imaging study. As described in this note, the use of this device could significantly improve the control of the rat head motion during CT acquisition even when the animal was anesthetized.

In addition, vascular images of small animals are generally acquired with administration of contrast media followed by scans that require several minutes to complete with dedicated microCT scanners. This is significantly slower than modern clinical CT systems which can acquire volumetric data from a patient within a few seconds, and therefore can catch both the arterial and venous phases following intravenous injection of an iodinated contrast bolus. The lower scan speed of the typical microCT systems, therefore, has led to the introduction and development of new lipid-based contrast media (Badea et al 2005, Weichert et al 1998) which have slower vascular clearance than the hydrophilic contrast media used for clinical studies. Although it is generally economical to use lipid-based contrast media for imaging mice (typically 0.2–0.3 ml), it sometimes presents financial challenges to image rat models that require approximately ten times the volume of the contrast media (typically 2–3 ml). Without financial considerations, the lipid-based contrast agent still has a great potential in contrast-enhanced CT studies with rat models, particularly using relatively slow animal CT systems. Thus, for our study, we tested the use of conventional water-soluble contrast media for assessing the vascular status of small animal models with microCT, to determine if this was an appropriate approach not requiring the use of more expensive lipid-based contrast media developed specifically for small animal CT.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Dedicated small animal CT system

All in vivo imaging in this study used the FLEX(tm) X-O(tm) CT system (Gamma Medica-Ideas, Inc., Northridge, CA). This microCT system has a tungsten target x-ray tube that produces x-rays within a cone beam having an angular extent of 24°. CT data were acquired with an x-ray source of 60 kVp and 530 μA for both noncontrast and contrast-enhanced CT acquisitions, respectively. A single frame of 512 projections for 2 min of continuous x-ray exposure was used for CT acquisitions. Volumetric CT images were reconstructed in a 512 × 512 × 512 format with voxel dimensions of 170 μm3 using a Feldkamp algorithm (Clack and Defrise 1994, Feldkamp et al 1984) provided by the microCT manufacturer. This system does not reconstruct images in ‘Hounsfield units’ (HU) common with clinical imaging; thus we calibrated our CT images using a simple cylindrical phantom at a size of a typical rat (50.8 mm diameter) that contains water, and all reconstructed images were converted to HU using the air and water values extracted from the phantom data. The HU conversion was solely intended to report our results in a unit commonly adopted for CT analysis.

2.2. Animals

The animal was always anesthetized during an imaging procedure to control gross motion and escape of the animal. Also, all animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). In our laboratory, anesthesia is typically applied with the animal inhaling isoflurane through a nose cone. Representative results from a total of three rats are included for three different tasks discussed in this note. For contrast agent infusion, a 26-gauge Abbocath catheter was implanted through the tail vein prior to positioning the animal and connecting to the mechanical syringe pump in the scanner.

2.3. CT-compatible stereotactic immobilization device

For cerebral imaging, we found that the absence of constraint allowed significant head motion and could seriously degrade in vivo CT acquisitions, due to breathing in either the supine or the prone position. The head motion without constraint was, for example, at least a few millimeters displacement in the transverse plane. We therefore developed a nonmetallic stereotactic immobilization device made of polyoxymethylene, which fixed the position of the head relative to the CT scanner with three vinyl positioning screws (figure 1). Our device differs from a stereotactic device described in Kamiryo et al (2001) for gamma knife applications because ours does not contain any metallic components. The device described in Rubins et al (2001) for microPET (positron emission tomography) applications is very similar to our device except that ours is positioned on an axial plane that does not involve the brain region, because even this plastic material (polyoxymethylene) attenuates x-ray photons that generate reduced image intensity where the device is positioned. Thus, unlike typical stereotactic devices that fix the head with screws in ear canals, our three screws are all in the same plane outside of the brain region so that no x-ray attenuation by this device could present reduced image intensity. The primary position of this immobilization device was determined by one vinyl screw between incisor teeth. The other two screws were placed and tightened on both sides of maxilla. This immobilization device was designed to minimize head motion and to minimize any image artifacts due to this device for imaging the brain region, and was used for all in vivo CT acquisitions.

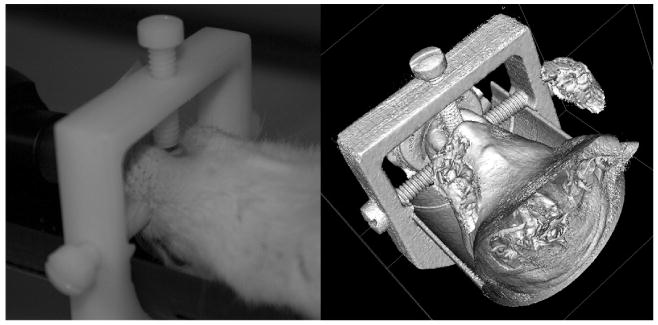

Figure 1.

A CT-compatible stereotactic immobilization device. Three vinyl screws fix the rat head in supine position. Photograph prior to CT acquisition (left) and a 3D surface rendering (right) using in vivo CT data are shown.

The effectiveness of the immobilization device was assessed by comparing the alignment of two volumetric CT reconstructions acquired at two sequential CT acquisitions acquired under constraint. This comparison was performed by aligning the CT data at the second time point with normalized mutual information derived from the first time point, using FMRIB's linear image registration tool (FLIRT) v5.4.2 with 12-parameter affine transformations (Jenkinson and Smith 2001, Smith et al 2004) from the Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (Oxford, UK). Although in theory only six degrees of freedom (rotations and translations) were required for image registration for our data because of the fixed image scale (voxel size), we performed the most complete registration permitted by the FLIRT package without any a priori assumptions of two images to be aligned. Then, the accuracy of the immobilization device was measured by examining the translations and rotations between a FLIRT-aligned image and a nonaligned image.

2.4. Noncontrast CT to visualize blood in subarachnoid space

In order to determine the minimum volume of blood that can be visualized with noncontrast CT, we first developed a rat model in which we implanted a catheter through the subarachnoid space. Through the catheter, we injected varied volumes of iopromide (300 mgI ml−1) as ‘surrogate blood’ with 0.1 ml increments in the range 0–0.8 ml for each in vivo CT acquisition. The animal was positioned with the catheter implanted, and CT was immediately acquired at each increment of iopromide injection. Iopromide was used as ‘surrogate blood’ because it is highly x-ray opaque so that the visualization is certain for this volume measurement.

We then performed a second study in which we performed CT to visualize the presence of blood in an intracranial hemorrhage model of rat brain prepared by injecting approximately 0.1 ml of freshly obtained arterial blood into the subarachnoid space. This study was performed using a rat model different from that used in the above experiment. A region of interest (ROI) analysis was performed by drawing elliptical ROIs over both the blood region (target) and the area surrounding the blood region (background). The mean HU values were compared between the target and background.

2.5. Contrast-enhanced CT to visualize blood vessels

We evaluated contrast enhancement of the cerebral vasculature with a conventional contrast agent (iopromide, 300 mgI ml−1). Since the in vivo vascular clearance of iopromide occurs rapidly with respect to the 2 min acquisition time of microCT, the FLEX(tm) X-O(tm) microCT system cannot capture the peak arterial opacification for all acquired projections following bolus administration of the contrast bolus. Thus, the contrast-enhanced CT acquisitions in this study were performed with iopromide infused continuously with a mechanical syringe pump (BSP-3, Braintree Scientific, Inc., Braintree, MA) at the rate of 1.2 ml min−1 during the entire CT acquisition. The start of infusion was simultaneous with the CT acquisition, and the total of 2.4 ml of iopromide was injected for 2 min of CT acquisition. A precontrast CT acquisition was also performed to visualize the effect of contrast media by comparing pre- and post-contrast images. Three animals followed this procedure, but we show one representative case that showed the highest contrast enhancement.

3. Results

3.1. Head immobilization during in vivo CT acquisitions

The nonmetallic immobilization device (figure 1) was very effective in fixing the position of the head of a rat during in vivo CT acquisitions. There were very small translational and rotational variations between the FLIRT-aligned image and the unaligned image with respect to the CT image obtained at the later time point. The transitional and rotational differences were less than 0.5 voxels (approximately 85 μm) and 0.5°, respectively. The reduced image intensity due to the plastic material (polyoxymethylene) of the immobilization device was visible in the reconstructed CT image (top portion of figure 2) where the device is positioned (figure 1).

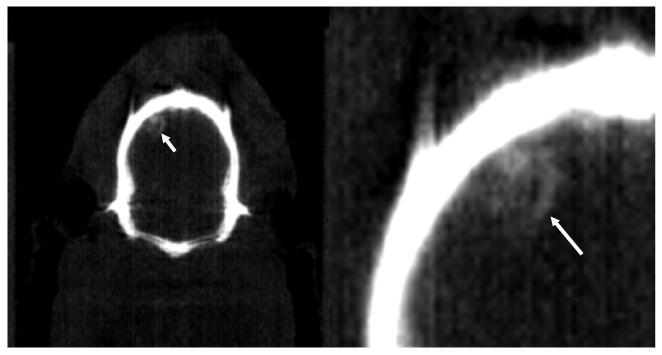

Figure 2.

‘Surrogate’ hemorrhage (iopromide, 300 mgI ml−1) in subarachnoid space shown in reconstructed CT images (CT window: 0–1500 HU). There was no iopromide in the subarachnoid space in the left image, but only 0.1 ml of iopromide in the right image indicated by a white arrow.

3.2. ‘Surrogate’ and intracranial hemorrhage

Figure 2 shows a representative CT scan of the rat brain following administration of a 0.1 ml ‘surrogate’ hemorrhage (iopromide, 300 mgI ml−1). The imaging study demonstrated that the ‘surrogate’ hemorrhage could also be visualized for all volumes in the range 0.1–0.8 ml. The ROI analysis over the site of ‘surrogate’ hemorrhage showed over 1250-HU enhancement between two images as shown in figure 2.

Similarly, we were able to visualize the presence of 0.1 ml arterial blood injected by a surgical method intracranially in the brain of a rat (figure 3). The ROI analysis over the site of femoral blood indicated by a white arrow in figure 3 and background region around the site of femoral blood showed approximately 400-HU enhancement. This measurement was performed without iodinated contrast to demonstrate the sensitivity of microCT for visualizing intracranial hemorrhage.

Figure 3.

A coronal view (left) of the presence of arterial blood in a noncontrast CT image (CT window: 0–1500 HU) indicated by a white arrow with a close-up view (right). The volume of femoral arterial blood injected was less than 0.1 ml.

3.3. Vascular contrast in carotid arteries and cerebral vessels

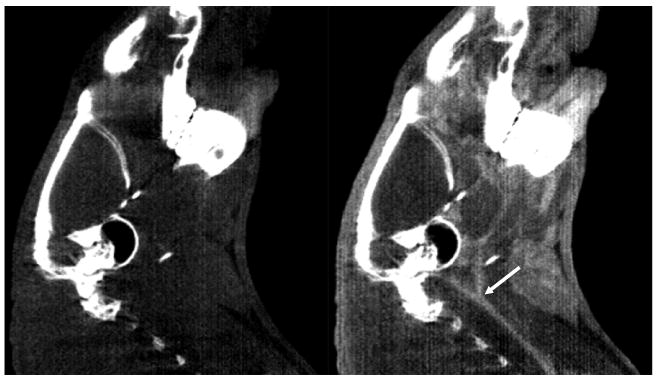

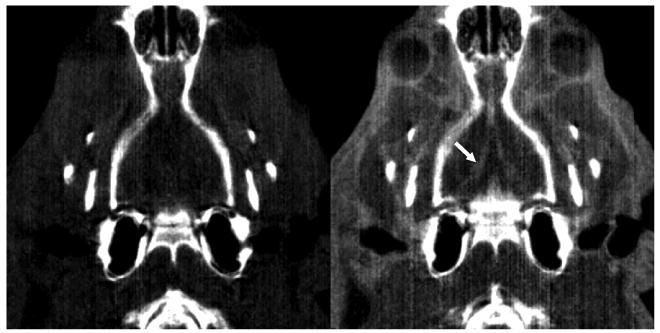

Continuous administration of iodinated contrast agent (iopromide, 300 mgI ml−1) over the entire CT acquisition (2 min) allowed us to visualize the cerebrovascular structure of a rat. The cerebrovasculature was not clearly visible with noncontrast CT imaging of the same rat. Specifically, both carotid arteries (common, internal and external) as well as some cerebral vessels are visualized with the contrast-enhanced CT in figures 4 and 5, respectively, but are either less clearly visualized or not visible when the CT images were acquired without the iodinated contrast. An ROI analysis over the area of bifurcation (indicated by a white arrow in figure 4) of the carotid arteries showed approximately 600-HU enhancement between noncontrast- and contrast-enhanced images. The smallest vessel size visible in these contrast-enhanced CT images (figures 4 and 5) was estimated at approximately 1 mm diameter.

Figure 4.

Sagittal views of carotid arteries (CT window: 0–1500 HU). These arteries are visible in contrast-enhanced CT (right), but not visible in noncontrast CT (left). A white arrow indicates the area of bifurcation of carotid arteries.

Figure 5.

Coronal views of cerebral blood vessels (CT window: 0–1500 HU). These blood vessels are only visible in contrast-enhanced CT (right), but not visible in noncontrast CT (left). A white arrow indicates the area of cerebral blood vessels only visible in contrast-enhanced CT.

4. Discussion

In this note, we describe a method of imaging rat models of cerebrovascular morphology and of hemorrhagic stroke using microCT. The techniques performed in this study rely on development and use of a nonmetallic stereotactic immobilization device to stabilize the head and to prevent motion blurring during acquisition of the CT data. Furthermore, it was useful for imaging the rat brain without contrast media to visualize intracranial blood introduced to simulate hemorrhagic stroke. A second application tested in this study used both cerebral stabilization with the immobilization device, as well as prolonged contrast infusion to visualize normal vasculature and vascular pathology in a rodent model of cerebral aneurysm. The amount of iodinated contrast media used in our study might be considered high; however in our knowledge there is no definitive report in the literature about the limit of iodine dosage on the kidney load for rats except that an ex vivo study suggesting a high iodine level, close to the amount we used in our study, may cause renal failure due to the decrease in blood flow and increase in red blood cell aggregation (Liss et al 1996). In our study, our animals tolerated the given dosage well, and all survived after injection. For the long-term serial studies, the animal health, not only the survival, after repeated high doses of contrast agent in addition to repeated radiation dose by x-ray, needs to be further investigated prior to launching such a study. We also note that our animals for these studies were healthy rats; thus the animals used for modeling disease may be more vulnerable to the effects of a large iodine injection, particularly near the end of their lifespan.

In a clinical setting, cerebral vasculature can be visualized in both the arterial and venous wash-out phases following a bolus injection of intra-arterial contrast media. Recapitulating this acquisition format in the rodent is exceedingly difficult given the significantly faster transit time of blood in the rodent relative to the 2 min acquisition time with microCT scanners having performance similar to the FLEX(tm) X-O(tm) system used in this study. There have been developments of fast microCT, using a slip-ring gantry and a fast flat-panel detector (Drangova et al 2007, Ford et al 2006, Greschus et al 2005, 2007, Kiessling et al 2004, Ross et al 2006); the fast microCT can also make a significant impact for imaging rodents with iodinated contrast media since the fast system can remove the need for the continuous infusion technique described in this note.

Diffusion-weighted MR imaging has shown itself as a promising imaging technique to visualize pathophysiologic changes associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in a rat model (van den Bergh et al 2005). A T2*-weighted MR imaging technique has been used in vivo with a rodent model of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) to visualize hematoma (Strbian et al 2007). Both of these MRI studies were performed with research NMR spectrometers at 4.7 T. An adaptation of these NMR systems for dedicated small animal imaging is a compact high-field MRI (microMRI) system. As shown with NMR spectrometers, microMRI can be used effectively to image accumulation of extravascular blood associated with hemorrhagic stroke, or for imaging vasculature without administration of contrast media. However, microMRI typically is considerably more expensive and requires longer scan times than microCT. For these reasons, the methods developed and tested in this study demonstrate the capabilities of microCT for imaging hemorrhagic stroke and intracranial vasculature in a rat using methods that are relatively simple, fast and economic, while providing information that is useful for evaluating animal models of cerebrovascular disease.

5. Conclusion

In vivo microCT imaging of the rat brain was performed with a CT-compatible stereotactic immobilization device. This technique allowed visualization of a subarachnoid hemorrhage model in live rats. The continuous administration of clinical iodinated contrast agent combined with the immobilization device also allowed visualization of intracranial vasculature. These in vivo microCT techniques have the potential to be useful for longitudinal evaluation of small animal models of new preventive or therapeutic methods for cerebrovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding support for this research project was provided through the UCSF Radiology Research and Education Fund, the National Cancer Institute (Grant K25 CA CA114254), the National Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering (Grant R01 EB00348), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Grant R01 NS055876) and a UC Discovery Grant (bio02-10300).

References

- Ahmed M, Masaryk TJ. Imaging of acute stroke: state of the art. Semin Vasc Surg. 2004;17:181–205. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badea CT, Fubara B, Hedlund LW, Johnson GA. 4-D micro-CT of the mouse heart. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:110–6. doi: 10.1162/15353500200504187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belayev L, Saul I, Busto R, Danielyan K, Vigdorchik A, Khoutorova L, Ginsberg MD. Albumin treatment reduces neurological deficit and protects blood-brain barrier integrity after acute intracortical hematoma in the rat. Stroke. 2005;36:326–31. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000152949.31366.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack R, Defrise M. Cone-beam reconstruction by the use of Radon transform intermediate functions. J Opt Soc Am A. 1994;11:580–5. [Google Scholar]

- De Clerck NM, Meurrens K, Weiler H, Van Dyck D, Van Houtte G, Terpstra P, Postnov AA. High-resolution X-ray microtomography for the detection of lung tumors in living mice. Neoplasia. 2004;6:374–9. doi: 10.1593/neo.03481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drangova M, Ford NL, Detombe SA, Wheatley AR, Holdsworth DW. Fast retrospectively gated quantitative four-dimensional (4D) cardiac micro computed tomography imaging of free-breathing mice. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:85–94. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000251572.56139.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldkamp LA, Davis LC, Kress JW. Practical cone-beam algorithm. J Opt Soc Am A. 1984;1:612–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ford NL, Graham KC, Groom AC, Macdonald IC, Chambers AF, Holdsworth DW. Time-course characterization of the computed tomography contrast enhancement of an iodinated blood-pool contrast agent in mice using a volumetric flat-panel equipped computed tomography scanner. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:384–90. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000197981.66537.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greschus S, et al. Potential applications of flat-panel volumetric CT in morphologic and functional small animal imaging. Neoplasia. 2005;7:730–40. doi: 10.1593/neo.05160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greschus S, Savai R, Wolf JC, Rose F, Seeger W, Fitzgerald P, Traupe H. Non-invasive screening of lung nodules in mice comparing a novel volumetric computed tomography with a clinical multislice CT. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:707–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–56. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo SP, Kim TS, Kim YS, Moon KS, Lee JK, Kim JH, Kim SH. Clinical utility of multislice computed tomographic angiography for detection of cerebral vasospasm in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2006;49:286–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-954826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiryo T, Han K, Golfinos J, Nelson PK. A stereotactic device for experimental rat and mouse irradiation using gamma knife model B—technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2001;143:83–7. doi: 10.1007/s007010170142. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennel SJ, Davis IA, Branning J, Pan H, Kabalka GW, Paulus MJ. High resolution computed tomography and MRI for monitoring lung tumor growth in mice undergoing radioimmunotherapy: correlation with histology. Med Phys. 2000;27:1101–7. doi: 10.1118/1.598974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling F, et al. Volumetric computed tomography (VCT): a new technology for noninvasive, high-resolution monitoring of tumor angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1133–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liss P, Nygren A, Olsson U, Ulfendahl HR, Erikson U. Effects of contrast media and mannitol on renal medullary blood flow and red cell aggregation in the rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1268–75. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan CL, Girgis J, Colbourne F. Delayed onset of prolonged hypothermia improves outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:432–40. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MJ, Gleason SS, Kennel SJ, Hunsicker PR, Johnson DK. High resolution X-ray computed tomography: an emerging tool for small animal cancer research. Neoplasia. 2000;2:62–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W, Cody DD, Hazle JD. Design and performance characteristics of a digital flat-panel computed tomography system. Med Phys. 2006;33:1888–901. doi: 10.1118/1.2198941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubins DJ, Meadors AK, Yee S, Melega WP, Cherry SR. Evaluation of a stereotactic frame for repositioning of the rat brain in serial positron emission tomography imaging studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;107:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strbian D, Tatlisumak T, Ramadan UA, Lindsberg PJ. Mast cell blocking reduces brain edema and hematoma volume and improves outcome after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:795–802. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh WM, Schepers J, Veldhuis WB, Nicolay K, Tulleken CA, Rinkel GJ. Magnetic resonance imaging in experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:977–83. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0539-x. discussion 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichert JP, Lee FT, Jr, Longino MA, Chosy SG, Counsell RE. Lipid-based blood-pool CT imaging of the liver. Acad Radiol. 1998;5(Suppl 1):S16–9. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(98)80047-0. discussion S28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Del Bigio MR. Intracortical hemorrhage injury in rats : relationship between blood fractions and brain cell death. Stroke. 2000;31:1721–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]