Abstract

Background

The therapeutic efficiency of anticancer NA strongly depends on their intracellular accumulation and conversion into 5’-triphosphates. Since active NATP cannot be directly administrated due to instability, we present here a strategy of nanoencapsulation of these active drugs for efficient delivery to tumors.

Methods

Stable lyophilized formulations of 5’-triphosphates of cytarabine (araCTP), gemcitabine (dFdCTP) and floxuridine (FdUTP) encapsulated in biodegradable PEG- or F127-cl-PEI nanogel networks (NGC and NGM, respectively) were prepared by a self-assembly procedure. Cellular penetration, in vitro cytotoxicity and drug-induced cell cycle perturbations of these nanoformulations were analyzed in breast and colorectal cancer cell lines. Cellular accumulation and NATP release from nanogel was studied by confocal microscopy and direct HPLC analysis of cellular lysates. Antiproliferative effect of dFdCTP-nanoformulations was evaluated in human breast carcinoma MCF7 xenograft animal model.

Results

Nanoencapsulated araCTP, dFdCTP and FdUTP demonstrated similar to NA cytotoxicity and cell cycle perturbations. Nanogels without drugs showed very low cytotoxicity, although NGM was more toxic than NGC. Treatment by NATP nanoformulations induced fast increase of free intracellular drug concentration. In human breast carcinoma MCF7 xenograft animal model, intravenous dFdCTP-nanogel was equally effective in inhibiting tumor growth at four times lower administered drug dose compared to free gemcitabine.

Conclusions

Active triphosphates of NA encapsulated in nanogels exhibit similar cytotoxicity and cell cycle perturbations in vitro, faster cell accumulation and equal tumor growth inhibitory activity in vivo at much lower dose compared to parental drugs, illustrating their therapeutic potential for cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: nanogel, cytarabine, gemcitabine, floxuridine, 5’-triphosphates, xenograft model

Introduction

Nucleoside analogues (NA) and nucleobases are widely used for the treatment of cancer (1). For instance, the pyrimidine analogue araC constitutes the cornerstone of induction therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia, while the fluorinated pyrimidine analogue gemcitabine has much broader indications, including lung, breast, pancreatic and bladder cancers. Finally, the fluoropyrimidine 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) continues to be one of the most widely prescribed cancer chemotherapeutic drugs in the world. These drugs are administered as inactive prodrugs entering cells by means of specific membrane nucleoside transporters (2). Once inside the cell, these compounds can be activated by different nucleoside kinases to produce biologically active diphosphorylated and triphosphorylated metabolites (3). Thus, the therapeutic efficacy of NA strongly depends on its intracellular transport and phosphorylation. Any ways to increase the intracellular concentration of active phosphorylated drug metabolites would increase clinical efficacy of cancer chemotherapy. Negatively charged nucleoside 5’-mono-, di- and triphosphates cannot permeate through the lipid-rich cellular membrane and they are immediately degraded in the gastrointestinal tract or in the blood circulation (4). Several strategies including pronucleotide approach, liposomal encapsulation, nanoparticulate or red blood cell-based delivery were previously evaluated to bypass the bottleneck in tumor accumulation of the activated drugs but, unfortunately, none of them found its way to clinic (5). The pronucleotide approach was to administer protected or lipophilic prodrugs of nucleoside 5’-monophosphates (6–8). However, this strategy showed many disadvantages such as degradation of pronucleotides in serum or tumor microenvironment, production of charged phosphodiester intermediates resistant to further chemical degradation and possible catabolism of 5’-monophosphates by 5’-nucleotidases (4). The second approach was to encapsulate the activated phosphorylated drugs in liposomes (9–12). Different caveats were encountered when working with these liposomal drugs. The nucleotides could not diffuse readily through the intact liposome membrane affecting the in vivo activity of encapsulated drugs. It was found that the size, surface charge and lipid composition had a strong influence on liposome clearance profile. In the third approach, 5’-mono- and triphosphates of NA were encapsulated in erythrocytes (13, 14). The major problem encountered in the use of natural cells as drug carriers was their efficient removal from blood circulation by the reticuloendothelial system.

We describe novel formulations of 5’-triphosphates of cytotoxic NA in nanogels that were capable to deliver and rapidly release these active drug metabolytes inside cancer cells. The nanosized hydrophilic networks composed of cross-linked cationic and neutral polymers have been initially applied to encapsulation and delivery of oligonucleotides (15). Recently, Vinogradov et al have demonstrated successful encapsulation of 5’-triphosphates of cytotoxic and antiviral NA in various biodegradable cationic nanogels (16). Together with these encouraging results, several recent publications confirmed that direct administration of 5’-triphosphates encapsulated in nanoparticles could increase therapeutic efficacy of NA (17, 18). The aim of this study was to determine whether nanogel formulations can supply effective doses of active NATP into various cancer cells. Here, we report that biodegradable nanogels (denoted as NGC and NGM) loaded with NATP of araC, dFdC, and FdU (prodrug of 5-FU) show similar cytotoxicity in vitro in breast and colorectal cancer cell lines and potentially higher in vivo antitumor activity than parental drug.

Material and methods

Materials

All chemical reagents and solvents, if not mentioned otherwise, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co (St.Louis, MO). Pluronic F127 was generous gift from BASF Corp. (Parsippany, NJ); arabinofuranosylcytosine (cytarabine, araC) was purchased from 3B Medical Systems (Lybertyville, IL), 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (floxuridine, FdU) from SynQuest Laboratories (Alachua, FL) and ATP BODIPY FL from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Nanogel preparation

Nanogel NGC carrier representing a chemically cross-linked network of PEG molecules and biodegradable segmented PEI connected by disulfide bridges (PEG-cl-PEI) was synthesized by the emulsification-solvent evaporation method (19) (Supplementary Materials, Fig. 1A). Nanogel NGM carrier contains lipophilic polymer core of Pluronic F127 surrounded by the covalently cross-linked network of PEG and biodegradable PEI prepared using micellar approach (20). Both nanogels have been fractionated by preparative SEC on Sephacryl S-300 column to isolate particles with hydrodynamic diameter in the range of 70–150 nm, neutralized with hydrochloric acid and lyophilized. Analytical characteristics of nanogels and drug nanoformulations are presented in Table 1. Rhodamine-labeled nanogels were prepared according to the previously described protocol (21).

Table 1.

Analytical characteristics of cationic nanogels and NATP nanoformulations

| Carrier | Nitrogen content, µmol/mga | Nanogel diameter, nmb | Drug loading, µg/mg nanoformulationc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unloaded | CTP-loaded | araCTP | FdUTP | dFdCTP | CTP | ||

| NGC | 6.1 | 100 ± 8 | 58 ± 2 | 102 | 190 | 42 | 66 |

| NGM | 5.5 | 187 ± 6 | 112 ± 3 | 64 | 134 | 52 | 154 |

Calculated based on elemental analysis data;

Measured by dynamic light scattering at 10 mg/ml or 1 mg/ml with CTP (PBS, means ± SD, n = 3).

Determined spectrophotometrically in water using extinction coefficients for corresponding NA

NATP synthesis

AraC, FdU and dFdC (Supplementary Materials, Fig 1B) were converted into 5’-triphosphates using the one-pot phosphorylation protocol with minor modifications (21). NATP were purified by the two step procedure using a short column with Sephadex A-25 (acetate form) equilibrated with 0.05M TBAA buffer, pH 6. The product was eluted from the column with a TBAA buffer gradient from 0.05 to 1.5M. The NATP-containing fractions were usually contaminated with co-eluted inorganic pyrophosphate; therefore, they were collected and applied directly into a short column with Silicagel C18 for desalting and eluted using a methanol gradient from 5 to 70%. Concentrated in vacuo NATP was precipitated in 1% sodium perchlorate in acetone as sodium salt. The purity of NATP products was more or equal to 90% according to ion-pair reverse phase HPLC and UV spectrophotometric analysis. Complete synthetic procedure and characterization of the nucleoside 5’-triphosphates will be reported elsewhere.

Drug encapsulation and nanoformulation stability

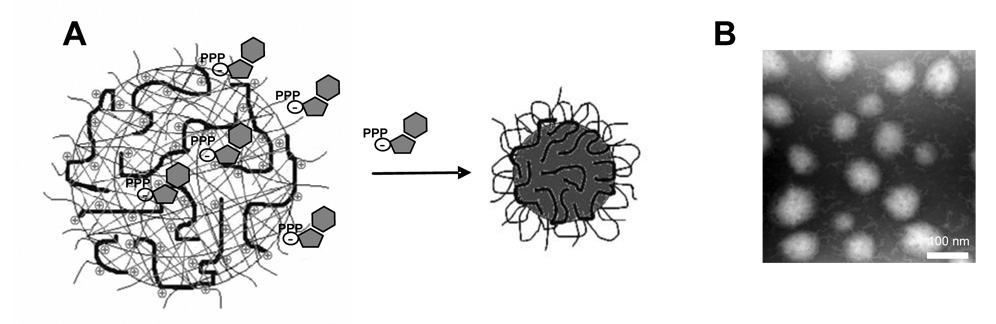

The following protocol was used for drug encapsulation into nanogels (Fig. 1). Equal volumes of aqueous solutions of nanogel (40 mg/ml) and NATP (10 mg/ml) in water were mixed together and incubated for 30 min on ice. The mixture was applied into NAP-25 cartridge and the high-MW fraction was eluted with water and lyophilized. Nucleoside content in nanogels (Table 1) was detected spectrophotometrically using extinction coefficient ε (λmax) values for gemcitabine: 9360 (268 nm), floxuridine: 7570 (268 nm), cytarabine: 9260 (272.5 nm), and cytidine: 9100 (271 nm) (22).

Figure 1.

Formulation of nanogels with 5’-triphosphates of nucleoside analogues. (A) Self-assembly of nanoformulations with NATP. (B) Transmission electron microscopy of the drug -loaded nanocarrier negatively contrasted by vanadate. Bar: 100 nm.

Stability of the drug nanoformulations in the presence of serum was evaluated by analytical SEC on Sephacryl S-500 column (1×25 cm) with UV detection at 280 nm in PBS buffer. NGC nanogel was complexed with ATP as described above, mixed with equal volume of 10% serum and analyzed immediately or following 90 min incubation at 37°C (Supplementary Materials, Fig.2).

Cell lines

The breast cancer cell lines MCF7 and T47D and the colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116, SW48 and SW480, all purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), were cultured in Dulbecco’s Minimum Essential Medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 1% L-glutamine and 2% penicillin-streptomycin on 25 cm2 flasks at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Nanogel internalization assays

Rhodamine-labeled nanogel internalization assay was conducted in MCF7 and HCT116 cancer cells for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were trypsinized, washed twice in PBS and acquired in a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Intracellular fluorescence analysis was performed with FlowJo 7.2.2 software (Treestar, Ashland, USA.).

Cellular accumulation and drug release was also examined by confocal microscopy in live MCF7 cells without fixation using a formulation of rhodamine-labeled nanogel NGC with the fluorescent ATP BODIPY FL prepared as described above. MCF7 cells were plated at a density of 50,000 cells per plate (Bioptechs, Butler, PA) and allowed to attach for 24 h prior to the treatment. Cells were incubated with 1 ml of 0.001% drug-nanogel formulations for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times with ice-cold PBS containing 1% BSA and the intracellular trafficking of nanogel and ATP release were investigated at two fluorescence modes for BODIPY and rhodamine dye (λex 549nm/λem 577nm) using Zeiss confocal LSM410 microscope (Iena, Germany) equipped with argon-krypton laser.

Gemcitabine internalization

Analysis of dFdCTP in the total NTP pool was performed using the modified method (23). MCF7 cells (2 × 106) were seeded in 6-well plate and treated with gemcitabine or NGC-dFdCTP formulation in full medium (1 µmol per well) for 2 and 6 h at 37°C. Two identical plates were used as parallels. Cells were trypsinized, collected at 400g (10 min, 4°C), washed and counted. Cells resuspended in 240µl water were treated with 80µl of 40% trichloroacetic acid and placed on ice for 20 min allowing protein and nucleic acids precipitation. After centrifugation at 16,000g (10 min, 4°C), supernatants were collected and extracted three times with 640µL of freshly prepared trioctylamine: freon (1,1,2-trichlorotrifluorethane) mixture (1:4, v/v). The aqueous part was analyzed by the ion-pair HPLC. The 250 µl-samples were injected on Zorbax C18 analytical column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 3 µm particle size) and dFdCTP was separated from other cellular triphosphates in a gradient from 35 to 85%B (30 min) using solutions of (A) 150 mM KH2PO4 /10mM TBAH, pH 6.1, and (B) 150 mM KH2PO4 /10mM TBAH, pH 5/20% methanol. Data were analyzed using the calibration curve for dFdCTP sample and recalculated according to the total sample volume and cell number; the final dFdCTP nucleotide content was expressed as pmol/106 cells.

In vitro growth inhibitory assay

Cell growth inhibition was determined using the MTT assay as previously described (24). Chemosensitivity was expressed as the effective drug concentration that inhibited cell proliferation by 50% (IC50 values) and was determined from concentration-effect curves generated using Prism 4 software (GraphPad).

Cell cycle distribution analysis

For analysis of DNA content and cell cycle distribution, MCF7 and HCT116 cells were treated with cytotoxic NATP-loaded nanogels, or nontoxic CTP-loaded nanogels, or NA drugs for 24 h at 37°C. After drug-exposure, 106 cells were resuspended in 2 ml of propidium iodide solution (50 µl/ml), incubated for 1 h at 4°C and analyzed using FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Cell cycle distribution and DNA ploidy status were calculated after exclusion of cell doublets and aggregates on a FL2-area/FL2-width dot plot using FlowJo 7.2.2 software (Treestar, Ashland, USA.).

In vivo tumor growth inhibition assay

The human breast carcinoma MCF7 cell line was used to determine an in vivo tumor growth inhibition effect of the gemcitabine nanoformulation. A single cell suspension of 5 × 106 cells in 400 µl of full medium containing 20% of Matrigel (Becton-Dickinson, San Diego, CA) was s.c. injected into mammary fat pads of female NIH-III mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), 6–8 weeks of age. Animal studies were carried out according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Mice were monitored daily for tumor growth, which appeared approximately three weeks after the cell injection. Animals were randomly divided into groups (n = 5) and received injections of PBS solution (control group) and well-tolerated doses of dFdC (6 mg/kg), dFdCTP/NGC (36 mg/kg; it contains 3 mg/kg of dFdCTP) and CTP/NGC (36 mg/kg; it contains 4 mg/kg of CTP) in the tail vein twice a week. The tumor volume was calculated based on the equation: TV = L/2 × W2 where L and W are length and width of tumor (mm) measured by callipers.

Results

Drug nanoformulations stability and cellular uptake

NGC and NGM nanogels schematic network and structures of 5’-triphosphates of NA are shown in Supplementary Materials (Fig.1). These anionic drug derivatives were encapsulated in the positively charged nanogel network by simple mixing of both components in aqueous solution. The compact particles of drug-loaded nanogels with diameters 60–110 nm contained up to 19% wt of active drug and could be stored in lyophilized form (Table 1).

Stability and release of nanogel-encapsulated NTP were analyzed by analytical SEC following the incubation with serum-containing medium. As shown in, Supplementary Materials (Fig.2) the SEC profiles of ATP-loaded nanogel mixed with 10% serum were similar for the two conditions tested: injected immediately (Fig. 2C) or after incubation at 37°C for 90 minutes (Fig. 2D). Compared to the ATP-loaded nanogel injected without serum (Fig. 2A), both samples showed a minor additional peak eluting in the position of low-MW ATP and its metabolites. Serum (2%) (Fig. 2B) had only a background absorbance, as well as non-loaded nanogel (data not shown). Thus, incubation at 37°C in serum did not affect significantly stability of the nanoformulations.

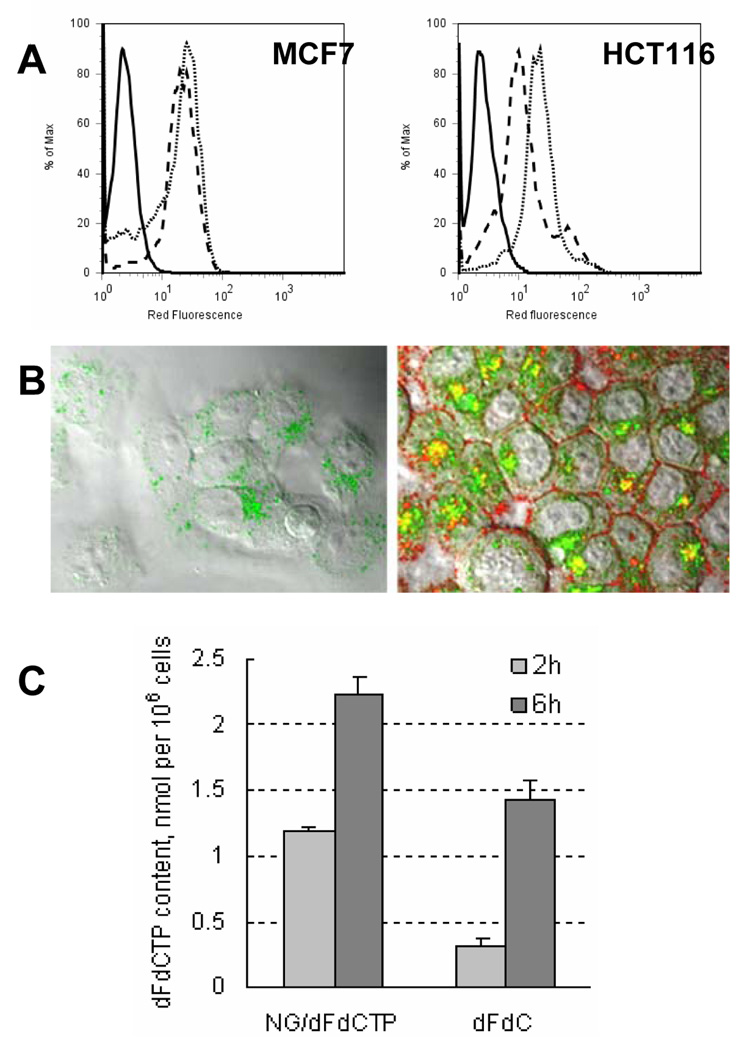

Figure 2.

Cellular uptake of cationic nanogels and encapsulated drugs and intracellular drug release from nanocarriers. (A) MCF7 and HCT116 cancer cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml of rhodamine-labeled NGC (dot line) or NGM (dash line) nanogels for 1 h and intracellular fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry. Control, non-treated cells are shown as continuous line. (B) Confocal microimage of MCF7 cells treated with 1.5 µg/ml of ATP BODIPY FL (I) or 10µg/ml of the nanogel formulation containing 1.5 µg/ml of ATP BODIPY FL (II) for 1 h at 37°C. Nanogel (NGC) was labeled by rhodamine isothiocyanate. Magnification: 100x. (C) Intracellular dFdCTP levels (nmol/106 cells) determined by analytical ion-pair HPLC following the treatment of MCF7 cells with 1 µmol of gemcitabine or equivalent amount of NGC-loaded dFdCTP for 2 and 6 h.

To study internalization of nanocarriers, MCF7 and HCT116 cancer cells were incubated with rhodamine-labeled NGC or NGM nanogels loaded with CTP. Flow cytometry studies revealed high intracellular levels of accumulation of both nanocarriers in MCF7 and HCT116 cancer cells (Fig. 2A). These data suggest that NGC or NGM nanocarriers are capable to deliver NATP drugs into cancer cells.

An efficient and rapid drug release from NTP-loaded nanogels was demonstrated by confocal microscopy in MCF7 cells incubated for 1 h with rhodamine-labeled NGC encapsulating the fluorescent ATP BODIPY FL. As shown in Fig.2B, the significant accumulation of drug-loaded nanogel (red and yellow fluorescence) was immediately accompanied by rapid appearance of high intracellular level of released ATP (green fluorescence). Following the accumulation of nanogels on the cellular membrane (red fluorescence), the major part of the released ATP was distributed in the cytoplasm already after 1 h of incubation (green diffused fluorescence), while some amount of drugs remained encapsulated in nanogels (yellow fluorescence) or enclosed in endosomes (green dotted fluorescence).

Direct measurement of the accumulated dFdCTP level was performed by HPLC analysis of the total cellular NTP pool after treatment of MCF7 cells with free gemcitabine or dFdCTP-loaded NGC nanogel. The level of dFdCTP in nanogel-treated cells was near 4 times higher than the de novo dFdCTP content in gemcitabine-treated cells 2 h post-incubation (Fig.2C). Interestingly, an approximately 5-fold increase in the concentration of intracellularly synthesized dFdCTP was detected in MCF7 cells treated with gemcitabine 6h post-incubation. However, this amount accounted only for 60% of the level of dFdCTP released from nanogel at this time point.

In vitro growth inhibitory assays

Cytotoxicity of araCTP, FdUTP or dFdCTP-loaded NGC and NGM nanocarriers was compared with CTP-loaded or non-loaded nanogels in MTT assay. As shown in Table 2, an increased cytotoxic effect on breast (MCF7 and T47D) and colorectal (HCT116, SW480 and SW48) cancer cells was generally observed when drug-loaded nanogels were compared to non-loaded nanocarriers. With all NATP-loaded NGC formulations, IC50 values were lowered by 36- to 233-fold, 44- to 126-fold, 36- to 330-fold, 300- to 315-fold and 57- to 200-fold for MCF7, T47D, HCT116, SW480 and SW48, respectively, compared to NGC treatment. With NATP-loaded NGM nanocarriers, IC50 values were lowered by 3- to 50-fold, 6- to 20-fold, 4- to 12-fold, 20- to 52-fold and 4- to 15-fold for MCF7, T47D, HCT116, SW480 and SW48, respectively. NGC and NGM nanogels loaded with CTP were even less toxic than non-loaded nanocarriers; the observed increase in cytotoxicity was more profound compared to non-loaded nanocarriers. NGC was distinctly less toxic than NGM in free and CTP-loaded forms in all experiments; it was chosen for cellular uptake and tumor growth inhibition experiments.

Table 2.

Cytotoxic activity of triphosphate-loaded nanogels (NG-NATP) and parental anticancer drugs

| Drug (µM)a | MCF7 | T47D | SW480 | SW48 | HCT-116 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| araC | 0.44 ± 0.1b | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.008 |

| NGC-araCTP | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| NGM-araCTP | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.08 | 0.2 ± 0.04 |

| 5-FU | 0.36 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 3 | 2.6 ± 0.8 |

| NGC-FdUTP | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| NGM-FdUTP | 2.4 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 4 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 0.7 |

| dFdC | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.01 ± 0.006 | 0.006 ± 0.002 | 0.005 ± 0.002 |

| NGC-dFdCTP | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.1 ± 0.01 |

| NGM-dFdCTP | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.07 ± 0.007 |

| Nanogel (µg/ml) | MCF7 | T47D | SW480 | SW48 | HCT-116 |

| NGC | 210 ± 40 | 76 ± 7 | 330 ± 200 | 600 ± 100 | 400 ± 40 |

| NGC-CTP | 1160 ± 400 | 650 ± 10 | 750 ± 110 | 810 ± 20 | 630 ± 40 |

| NGM | 30 ± 10 | 20 ± 9 | 10 ± 2 | 100 ± 60 | 30 ± 8 |

| NGM-CTP | 59 ± 6 | 39 ± 20 | 54 ± 8 | 120 ± 23 | 36 ± 4 |

The drug concentration was calculated based on the drug content in nanogels and Mw of NATP

IC50 values represent means ± SD of three separate experiments

As shown in Table 2, drug-loaded nanogels showed high cytotoxic activities in all studied cells with IC50 values in the nM range or, in some cases, lower than 5 µM. Parental drugs showed IC50 values in a similar range. No major differences were observed between NGC and NGM-loaded nanocarriers. AraCTP- and dFdCTP-loaded nanocarriers showed equal or slightly increased IC50 values compared to cytarabine and gemcitabine. FdUTP-containing nanocarriers also showed equal or slightly elevated IC50 values compared to 5-FU; however, in SW480 and HCT116 cells, their cytotoxic activity was greater than that observed with 5-FU. These data indicate that NGC and NGM nanogels encapsulating cytotoxic NATP have similar cytotoxic activities compared to parental drugs.

Cell cycle distribution analysis

NATP-loaded nanocarriers provoked similar to the parental drugs drug-induced cell cycle perturbations in breast and colorectal cancer cells. As shown in Table 3, cytarabine treatment induced a substantial accumulation of MCF7 and HCT116 in S-phase. This accumulation occurred mostly at the expense of the G0/G1 fraction. Similar features were observed when both cell lines were exposed to NGC-araCTP or NGM-araCTP. However, the level of S-phase arrest was lower in HCT116 cells exposed to NGM-araCTP. Treatment of MCF7 cells with 5-FU induced a slightly increase of the G0/G1 fraction, while, in HCT116 cells, the drug mainly induced accumulation in the S-phase. In both cases, these alterations were produced at the expense of the G2/M cell fraction. In contrast, MCF7 and HCT116 cells treated with NGC-FdUTP and NGM-FdUTP showed a significant increase in G2/M cell fraction. In HCT116 cells, these compounds simultaneously induced an accumulation of cells in the S-phase.

Table 3.

Cell cycle distribution after nanogel-drug treatment by flow cytometry

| MCF7 | HCT116 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0/G1 b | S-phase | G2/M | G0/G1 | S-phase | G2/M | |

| Control | 44 ± 7 | 42 ± 6 | 14 ± 5 | 60 ± 11 | 29 ± 11 | 11 ± 4 |

| araC | 8 ± 4 | 73 ± 7 | 19 ± 3 | 24 ± 4 | 75 ± 4 | 0 |

| NGC-araCTP | 33 ± 8 | 63 ± 2 | 4 ± 5 | 25 ± 1 | 75 ± 1 | 0 |

| NGM-araCTP | 1 ± 1 | 87 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 56 ± 1 | 44 ± 1 | 0 |

| 5-FU | 48 ± 4 | 40 ± 1 | 12 ± 2 | 33 ± 5 | 63 ± 6 | 5 ± 1 |

| NGC-FdUTP | 43 ± 2 | 26 ± 2 | 30 ± 1 | 43 ± 1 | 34 ± 1 | 22 ±2 |

| NGM-FdUTP | 42 ± 2 | 33 ± 1 | 24 ± 2 | 18 ± 4 | 53 ± 3 | 24 ± 1 |

| dFdC | 64 ± 7 | 34 ± 9 | 2 ± 3 | 56 ± 2 | 40 ± 3 | 3 ± 1 |

| NGC-dFdCTP | 50 ± 6 | 48 ± 6 | 2 ± 1 | 62 ± 6 | 38 ± 6 | 0 |

| NGM-dFdCTP | 50 ± 8 | 48 ± 6 | 2 ± 2 | 66 ± 5 | 33 ± 6 | 1 ± 1 |

| NGC-CTP | 51 ± 3 | 41 ± 6 | 7 ± 3 | 42 ± 8 | 46 ± 8 | 12 |

| NGM-CTP | 51 ± 3 | 41 ± 5 | 8 ± 2 | 48 ± 1 | 40 ± 5 | 12 ± 4 |

Cells were treated with 1 µM of each compound for 24 h and analyzed

IC50 values represent means ± SD of two separate experiments

Gemcitabine treatment induced accumulation of MCF7 cells in G0/G1 fraction associated with a reduction of cells within the S and G2/M phases. Instead, NGC-dFdCTP and NGM-dFdCTP nanocarriers induced not only a slight arrest at the G0/G1 fraction but also an accumulation in S-phase. Likewise, gemcitabine-treated HCT116 cells arrested the cell cycle in S-phase at the expense of the G2/M fraction. Similar features were observed when this cell line was treated with NGC-dFdCTP and NGM-dFdCTP nanoformulations. Thus, all these results demonstrate that, although NATP-loaded nanogels sometimes induced similar cell cycle perturbations compared to the parental drugs, they showed also some distinct nanocarrier-specific features.

In vivo tumor growth inhibition assay

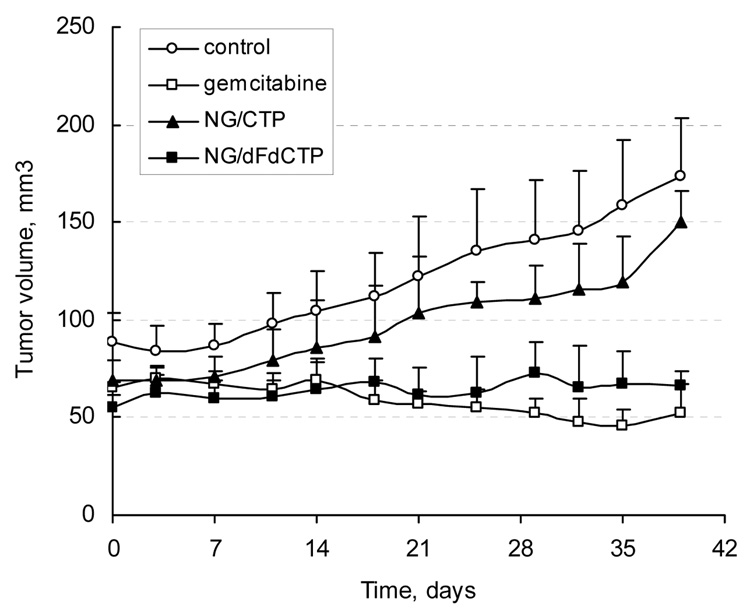

The tumor growth inhibition following multiple i.v.-administration of dFdCTP-loaded NGC nanogel was studied in the human breast carcinoma MCF7 xenograft mouse model. Median tumor volume changes in control and treated-mice are shown in Fig. 3. Compared to control group, administration of gemcitabine in close to therapeutic dose induced a significant tumor growth inhibition and reduction. Injection of the well-tolerated dose of dFdCTP-NGC (36 mg/kg) demonstrated statistically similar to gemcitabine inhibitory effect (P=0.096). However, the effective molar drug concentration in this formulation was 4 times lower than the equally effective dose of gemcitabine. CTP-Nanogel showed some effect that was not, however, statistically significant compared to the control group. Statistically significant (P<0.0001) differences were observed between the control group and groups including gemcitabine and dFdCTP-NGC-treated animals. Thus, NGC nanocarrier could efficiently deliver cytotoxic NATP to MCF7 xenograft tumors following systemic administration and demonstrated comparable to gemcitabine activity at significantly lower dose. There was no significant body weight loss among the groups throughout the experiment.

Figure 3.

Tumor growth inhibition exerted by active drug nanoformulations of nucleoside analogues. Animal groups (n = 5) with developed human breast carcinoma xenograft (MCF7) tumors were injected twice a week with dFdCTP-NGC formulation (36 mg/kg, 6 µM drug), or free gemcitabine (6 mg/kg, 23 µM drug). Phosphate-buffered saline and an equivalent amount of CTP-NGC were used as controls.

Statistical analysis was performed by applying two-tailed unpaired t-test (differences with P<0.05 were considered significant) and F-test to compare variances in groups using the Prism 4 software (GraphPad). The following P values were obtained: 0.002 (PBS/dFdC), 0.368 (PBS/CTP-NGC), <0.0001 (PBS/dFdCTP-NGC), 0.096 (dFdC/dFdCTP-NGC) and 0.0003 (dFdCTP-NGC/CTP-NGC).

Discussion

Development of novel tumor-targeted chemotherapies is required to achieve better drug accumulation in tumors and to overcome drug resistance to commonly used anticancer drugs. Many intravenous polymeric drug formulations were found to efficiently accumulate in vascularized tumors through their leaky blood vessels owing to the “enhanced permeability and retention” (EPR) effect (25). We describe here application of hydrophilic polymeric nanogels for delivery of anticancer cytotoxic NA in their active 5’-triphosphate form. Our results show that cationic nanogels effectively encapsulate, deliver and release NATP of cytarabine, floxuridine and gemcitabine inside breast and colorectal cancer cell lines inducing an in vitro cytotoxic activity and cell cycle perturbations similar to those observed for parental drugs. In some cases, these cell cycle alterations were specific for drug-loaded nanogel formulations, although nanogels by themselves demonstrated an extremely low cytotoxicity. Rapid drug release was detected immediately following the nanogel internalization that could substantially contribute to the observed effects. Finally, intravenous dFdCTP-loaded nanogel demonstrated efficient tumor growth inhibition in human breast tumor xenograft-bearing mice at significantly lower drug dose compared to free parental gemcitabine.

Nanogels can effectively encapsulate 5’-triphosphates of NA at simple mixing of both solutions in the amount up to 0.3 mmol/g, forming polyelectrolyte complexes between protonated amino groups in the polymer network and ionized phosphate groups of NATP (Fig.1). Following charge neutralization, the swollen nanogel network collapses forming hydrophobic drug-loaded core surrounded with PEG network (20). Nanogel-NATP complexes are relatively stable in serum and capable of protecting the 5’-triphosphates from the immediate degradation by ubiquitous phosphatases (21). Once internalized, the nanogels’ disulfide bonds rapidly degrade in the presence of cytoplasmic glutathione into non-toxic PEG-g-PEI conjugates having MW below the kidney excretion limit. In vitro NATP drug release from nanogel is initially rather fast, accounting for 60–70% during the first 24 h, and the remaining 30–40% during the next 48 h (16). An approximately 2/3 of NATP was released from nanogel during cytotoxicity assays exhibiting similar to NA cytotoxic effect in breast and colorectal cancer cells. A direct evidence of higher dFdCTP-NGC accumulation in the MCF7 cells was obtained by the extraction of total cellular NTP/NATP and HPLC analysis of dFdCTP in the pool. Only at later time points, de novo synthesis of dFdCTP from gemcitabine was efficient enough to reduce the difference from 300 (2 h) to 40% (6 h) (Fig.2C). Our data demonstrated an efficient cellular uptake of nanogel-loaded NTP and sustained release of phosphorylated drug molecules. We observed a considerable buildup of nanogels on the surface of cellular membrane and in endosomal compartments. This accumulation was accompanied by a significant drug release in the cytoplasm. Our previous studies demonstrated that the drug release can be mediated and enhanced by interaction with cellular membrane components (21). Although the mechanism of this release is not yet clear, nanoparticles consisted of PEI become endoosmolytic at the decrease of endosomal pH and capable to release drug molecules in the cytoplasm (26). Intracellular biodegradation of nanoparticles may be an additional factor accelerating the drug release.

Most NATP-nanogel formulations showed equal to cytarabine, gemcitabine or 5-FU IC50 values in two breast and three colorectal cancer cell lines. These results are in accordance to previous data showing that nanogel formulations containing AZTTP were cytotoxic against two breast cancer cell lines (21, 26). The significant increase in cytotoxic activities of AZTTP-nanogel formulations compared to AZT alone can be explained by low levels of the de novo synthesis of AZTTP in MCF7 and MDA-MB-232 cells. Our observed IC50 values may also reflect a cell-specific efficacy of the intracellular de novo NATP synthesis from NA. Moreover, in our study, the induced cell cycle perturbations, although similar to that of the parental drugs, were specific to drug-loaded nanocarriers in certain details. Whether these alterations may reflect differences in NATP accumulation levels following the treatment with NATP-releasing nanogels or parental drugs or effects of nanocarriers will be the subject of future investigations.

dFdCTP-nanogel showed an efficient systemic delivery of activated gemcitabine to human breast tumor xenografts. One explanation may be that nanogel particles were capable to actively accumulate in tumors because of the EPR effect. They could pass through fenestrations in the tumor blood vessels and release drug molecules into the interstitial space (27). This strategy of transporting anticancer NA would lead to a higher specificity and chemotherapeutic efficacy than injection of free drugs. Many factors such as distribution of blood vessels, blood flow, capillary permeability, interstitial pressure, and lymphatic drainage may affect drug exposure and effect of nanocarriers in normal tissues and in tumors (28, 29). Additional studies are required to evaluate pharmacokinetic properties of nanogel formulations and the drug exposure in normal tissues. The NATP-nanogels delivery and drug release in tumor cells presents an evident advantage because the cytotoxic effect of activated drugs is exerted very fast. Further improvements in tumor accumulation of nanocarriers, drug pharmacokinetics and cellular entry should result in higher drug accumulation of activated metabolites in tumor interstitium and more efficient tumor growth inhibition.

Different caveats should be considered and additional research is required for evaluation of anticancer applications of NATP-nanogels and, first of all, a potential cytotoxicity of nanogel carriers. Their toxicity profile may depend on polymer structure and the type of exposed cells. In fact, we found that NGM with structural hydrophobic elements was more toxic than NGC in many studied cancer cells. A second caveat is that drug nanoformulations could be as active in normal cells as in tumor. This problem could be solved by incorporating tumor-targeting ligands and site-specific release mechanism into nanogels, e.g. by coating nanogels with peptides or antibodies that target overexpressed receptors or specific epitopes on the surface of tumor cells.

In summary, we demonstrated that drug-loaded nanogels could deliver the active triphosphates of therapeutic NA into breast and colorectal cancer cells inducing an in vitro cytotoxic activity similar to that observed with the parental drug. Besides, the triphosphate-loaded nanoformulations exhibited a higher activity than NA drugs in animal models. These results illustrate the therapeutic potential of activated NA drugs formulated in nanosized biodegradable polymeric carriers for cancer chemotherapy. Given the potency observed with these drug nanoformulations, their application would resolve many of the problems associated with NA chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported in part by the NIH RO1 grant CA102791-05 (for S.V.V.). We thank Janice A. Taylor of the Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Core Facility at the UNMC for providing assistance with confocal microscopy and the Nebraska Research Initiative and the Eppley Cancer Center for their support of the Core Facility.

Financial support: National Cancer Institute R01 grant CA102791 (S.V.V.).

Abbreviations List

- NA

nucleoside analogues

- FdU

floxuridine

- dFdC

gemcitabine

- araC

cytarabine

- AZT

3′-azidothymidine

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEI

polyethylenimine

- F127

Pluronic® F127

- NTP

nucleoside 5’-triphosphate

- NATP

nucleoside analogue 5’-triphosphate

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- TBAA

tri-n-butylammonium acetate.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: S.V.V. is a shareholder of Supratek Pharma Inc., the owner of Nanogel patent.

References

- 1.Galmarini CM, Mackey JR, Dumontet C. Nucleoside analogues and nucleobases in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00788-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastor-Anglada M, Cano-Soldado P, Molina-Arcas M, et al. Cell entry and export of nucleoside analogues. Virus Res. 2005;107:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuda A, Sasaki T. Antitumor activity of sugar-modified cytosine nucleosides. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:105–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier C, Balzarini J. Application of the cycloSal-prodrug approach for improving the biological potential of phosphorylated biomolecules. Antiviral Res. 2006;71:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galmarini CM, Mackey JR, Dumontet C. Nucleoside analogues: mechanisms of drug resistance and reversal strategies. Leukemia. 2001;15:875–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahard D, McGuigan C, Balzarini J. Aryloxy phosphoramidate triesters as pro-tides. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2004;4:371–381. doi: 10.2174/1389557043403936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galmarini CM, Clarke ML, Santos CL, et al. Sensitization of ara-C-resistant lymphoma cells by a pronucleotide analogue. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:149–154. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peyrottes S, Egron D, Lefebvre I, Gosselin G, Imbach JL, Perigaud C. SATE pronucleotide approaches: an overview. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2004;4:395–408. doi: 10.2174/1389557043404007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erion MD, van Poelje PD, Mackenna DA, et al. Liver-targeted drug delivery using HepDirect prodrugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:554–560. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwendener RA, Horber DH, Odermatt B, Schott H. Oral antitumour activity in murine L1210 leukaemia and pharmacological properties of liposome formulations of N4-alkyl derivatives of 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1996;122:102–108. doi: 10.1007/BF01226267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwendener RA, Schott H. Lipophilic 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl cytosine derivatives in liposomal formulations for oral and parenteral antileukemic therapy in the murine L1210 leukemia model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1996;122:723–726. doi: 10.1007/BF01209119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JX, Sun X, Zhang ZR. Enhanced brain targeting by synthesis of 3',5'-dioctanoyl-5-fluoro-2'-deoxyuridine and incorporation into solid lipid nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002;54:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Flora A, Zocchi E, Guida L, Polvani C, Benatti U. Conversion of encapsulated 5-fluoro-2'-deoxyuridine 5'-monophosphate to the antineoplastic drug 5-fluoro-2'-deoxyuridine in human erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:3145–3149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraternale A, Rossi L, Magnani M. Encapsulation, metabolism and release of 2-fluoro-ara-AMP from human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1291:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(96)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Nanosized cationic hydrogels for drug delivery: preparation, properties and interactions with cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinogradov SV, Zeman AD, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Polyplex Nanogel formulations for drug delivery of cytotoxic nucleoside analogs. J Control Release. 2005;107:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couvreur P, Stella B, Reddy LH, et al. Squalenoyl nanomedicines as potential therapeutics. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2544–2548. doi: 10.1021/nl061942q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillaireau H, Le Doan T, Couvreur P. Polymer-based nanoparticles for the delivery of nucleoside analogues. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:2608–2617. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli E, Han HY, Zeman AD, Vinogradov SV. Formulations of biodegradable Nanogel carriers with 5'-triphosphates of nucleoside analogs that display a reduced cytotoxicity and enhanced drug activity. J Control Release. 2007;121:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinogradov SV, Kohli E, Zeman AD. Comparison of Nanogel Drug Carriers and their Formulations with Nucleoside 5'-Triphosphates. Pharm Res. 2006;23:920–930. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9788-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinogradov SV, Kohli E, Zeman AD. Cross-linked polymeric nanogel formulations of 5'-triphosphates of nucleoside analogues: role of the cellular membrane in drug release. Mol Pharm. 2005;2:449–461. doi: 10.1021/mp0500364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Merck Index. 13th Ed 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Losa R, Sierra MI, Jion MO, Esteban E, Buesa JM. Simultaneous determination of gemcitabine di- and triphosphate in human blood mononuclear and cancer cells by RP-HPLC and UV detection. J Chromatog B. 2006;840:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Twentyman PR, Fox NE, Rees JK. Chemosensitivity testing of fresh leukaemia cells using the MTT colorimetric assay. Br J Haematol. 1989;71:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb06268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinogradov SV. Polymeric nanogel formulations of nucleoside analogs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:5–17. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1441–1454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain RK. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Sci Am. 1994;271:58–65. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0794-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain RK. Delivery of molecular and cellular medicine to solid tumors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;26:71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.