Abstract

Objectives

To examine multiple measures of acculturation and their association with walking to school in a large population-based sample in San Diego, California.

Methods

The sample consisted of predominantly Latino children and their parents (N=812) who participated in a study to maintain healthy weights from kindergarten through 2nd grade (2004–2007). Acculturation and walking/driving to and from school were assessed through parent-proxy surveys.

Results

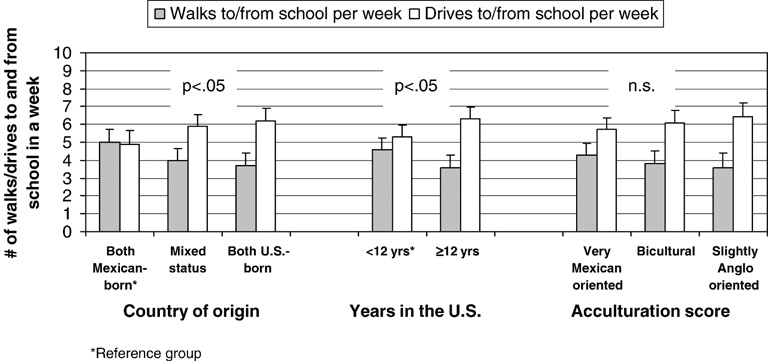

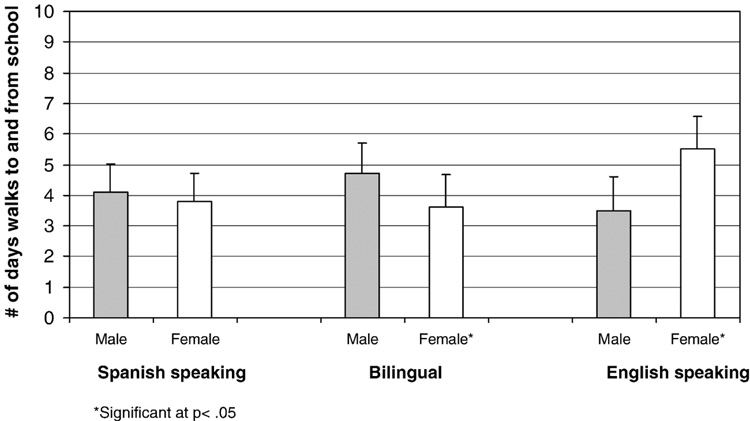

Children of foreign-born child-parent dyads walked to school more frequently than their counterparts (F=7.71, df= 5, 732, p<.001). Similarly, parents who reported living in the U.S. for less than or equal to 12 years reported more walking to school by their children compared with parents living in the U.S. for more than 12 years (F=10.82, df= 4, 737, p<.001). Finally, English-speaking females walked to school more frequently than Spanish-speaking and bilingual females.

Conclusion

This study explores Latino children’s walking to and from school using four measures of acculturation. In this cross-sectional study, being less acculturated was associated with more walking to school among children living in South San Diego County.

Keywords: Walking to school, acculturation, Latino children, health behavior

INTRODUCTION

Daily school commute represents an opportunity for continuous moderate physical activity (PA) for school-aged children (Tudor-Locke et al., 2001). Children who walk for school commute engage in more moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per week than those children who are driven to school (Cooper et al., 2005; Saksvig et al., 2007; Tudor-Locke et al., 2001). Yet, consistent with the upward trend in the incidence of childhood overweight, rates of active transportation for school commute have declined (CDC, 1998). In 1969, half of school-aged youth and adolescents in the U.S. walked/bicycled to and from school compared with 16% in 2001 (US Environmental Protection Agency).

Engaging in less PA, Latino adolescents spend more time being sedentary (e.g., television watching) compared to whites (Carvajal et al., 2002; Gordon-Larsen et al., 1999). This pattern also extends to Latino adults in the U.S. (Crespo, 2001). Other findings suggest that PA differs by acculturation level, but findings are mixed due to differences in acculturation measures. Crespo and colleagues (2001) used language preference at home, birthplace, and years in the U.S. to quantify acculturation. Using all three measures of acculturation, less acculturated individuals reported higher levels of inactivity during leisure time compared to more acculturated Latinos and Spanish-speakers who reported being more sedentary than English-speakers. Berrigan et al. (2006a) found a similar trend when they examined associations between language-based acculturation and leisure versus non-leisure time PA. However, the same study showed that less acculturated Latinos engage in higher levels of walking/bicycling for errands and standing/walking around during non-leisure time than more acculturated individuals. When using an acculturation scale (Marin et al., 1987), Marquez and McAuley (2006) showed that less acculturated Latinos reported engaging in more habitual PA (including household and occupational) than more acculturated individuals.

Studies involving Latino youth are largely limited to adolescents. Gordon-Larsen et al. (2003) examined country of origin and found that Mexican-born adolescents watched less television and engaged in fewer bouts of low intensity PA than U.S.-born adolescents. Using generation status, Allen et al. (2007) showed that first and second generation Latino adolescents engaged in less PA (past week) than third generation Latino and white adolescents. Unger et al. (2004) used the U.S. orientation subscale of the AHIMSA Acculturation Scale and concluded that acculturated Latino youth engaged in less PA (past week) compared to their less acculturated counterparts. Using the same measure, Carvajal et al. (2002) reported no association between acculturation and adolescents engaging in heavy exercise (four/more days), or light exercise (five/more days in the last week).

As the number of immigrants in the U.S. grows and the acculturative trajectories of the immigrant population diversify, studies that assess acculturation from a multi-dimensional perspective are warranted. Given that the acculturation process involves cultural and psychological changes, the construct may not be adequately captured using a single measure of acculturation (Berry, 2006). Acculturation scales (e.g., Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans; Cuéllar et al., 1980) have been developed to assess factors (e.g. cognition, identity, attitudes and stress) likely to be involved in the acculturation process. However, for lack of a gold standard that best quantifies acculturation, inconsistencies across and within studies continue to exist (Norman et al., 2004).

This study examined the following four measures of acculturation in determining the relationship between acculturation and walking to and from school: (1) parent-child dyads by country of origin; (2) child’s language use with family; (3) parent’s years living in the U.S; and (4) parent’s acculturation score as measured using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II (ARSMA-II; Cuéllar et al., 1995). To our knowledge, this is the first published study examining the relationship between walking to and from school and acculturation among children.

As acculturating families adapt more mainstream health behaviors, increasing acculturation may involve less engagement in active transportation. Therefore, when examining acculturation by parent-child dyads by country of origin, parent’s years living in the U.S. and parent’s acculturation score, we hypothesized that more acculturated families would report less active transportation by their child compared to their counterparts. Conversely, given possible barriers to navigating the environment with less English proficiency, it was hypothesized that children who preferred speaking Spanish would engage in less active transportation than English-dominant or bilingual children.

METHODS

Study Design

The current cross-sectional study used baseline data collected from parents recruited into a randomized community intervention whose aim was to maintain the healthy weights of kindergarten aged through second-grade children.

Sample

The target community was comprised of 13 schools in three San Diego school districts. All of the schools provided bus transportation to and from school. School sampling eligibility was based on: 1) Latino enrollment of at least 70%, 2) not having participated in an obesity-related study in the past four years, including a walk-to-school program, and 3) a defined attendance boundary. Low- and middle-income families were recruited regardless of their ethnicity. Family was defined as the presence of at least one caregiver and one child between kindergarten and 2nd grade. Recruited families had no major health conditions, resided within the school attendance boundary and had no plans to move away from the attendance boundary within the year. The study recruited 812 Latino parents-child dyads. Sample characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and acculturative characteristics for Latino children from kindergarten through 2nd grade and their parents (N=800). San Diego, California, 2004–2007.

| Children | Parents | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Mean age in yrs (SD) | 6.0 (0.9) | 34.4 (7.7) |

| % Female | 50% (401) | 97% (776) |

| % born in the U.S. | 86% (691) | 28% (226) |

| BMI (%) | ||

| Underweight (< 5th percentile) | 2% (15) | |

| Normal ( ≥5th-85th) | 52% (417) | 26.6% (213) |

| At risk for overweight (>85th and <95th) | 17% (135) | 32.9% (263) |

| Overweight (≥95th) | 29% (229) | 40.5% (324) |

| Employed full or part-time | n/a | 38% (305) |

| Income >$1500 | n/a | 38% (285) |

| High school educated | n/a | 65% (518) |

| Acculturation | ||

| Percent parents who have lived in U.S. ≥12 years | n/a | 57% |

| Parent acculturation score | ||

| Very Mexican oriented | n/a | 61% |

| Mexican-oriented bicultural | n/a | 26% |

| Slightly Anglo oriented | n/a | 10.5% |

| Anglo oriented bicultural | n/a | 2% |

| Assimilated/Anglicized | n/a | 0.5% |

| 13% both Mexican-born | ||

| Percent by country of origin | 59% mixed status | |

| 28% both U.S. born | ||

| 23% Spanish | ||

| Child's primary language spoken with family | 19% both | |

| 58% English | ||

Procedures

Parents were given a pencil and paper survey that was completed on school grounds. The survey was available in English and Spanish and included demographic questions and measures of acculturation, PA, and transportation. Participants signed consent forms approved by the Institutional Review Board of San Diego State University. Bilingual research assistants helped administer surveys taking, on average, one hour to complete. Participants were given $20 for completing the survey.

Measures

Acculturation was measured as follows

(1) parent-child pairs by country of origin: both Mexico-born, mixed status (Mexico-born parent and U.S.-born child) or both U.S.-born. Three cases were excluded with a different mixed status (U.S-born parent and Mexican-born child); (2) child’s language use with family: English, Spanish or bilingual; (3) parent’s years in the U.S. recoded as less than 12 years in the U.S. versus equal to/more than 12 years; and (4) parent’s acculturation assessed using the ARSMA-II developed by Cuéllar et al. (1995). This 30-item scale was selected for our target population (Mexicans/Mexican-Americans) for the following rationale: 1) culturally appropriateness and validation in two previous studies (Ayala et al., 2004; Elder et al., 2000), 2) demonstration of adequate psychometric properties (α=0.72) for a scale that measures acculturation from a multidimensional perspective (language use, ethnic identity, ethnic affiliation, contact with country of origin), and 3) the ability to differentiate between traditional Mexicans/Mexican-Americans and bicultural Mexican/Mexican-Americans given its bidirectional coding scheme. Responses were made on a 5-point scale and summed into two composite scores. Cuéllar suggests five cut-off points; however most participants fell into the three less acculturated categories (very Mexican, Mexican-bicultural, slightly Anglo). Parents in the last two categories (Anglo-bicultural and assimilated/Anglicized) were omitted from the analysis (n=22) due to small sample size.

Walking versus vehicle transportation to school

The survey items measuring transportation to school asked, “In a typical week, how many days does your child (1) …get to school by a) walking, and b) riding in a car/bus; and (2) …get home from school by a) walking and b) riding in a car/bus?” The “to” and “from” items were collapsed to compute a total score that ranged from 0 to 10 possible trips in one school week (0 to 5 days to school + 0 to 5 days from school = total of 10 possible trips to and from school by walking versus vehicle transportation). Walking versus vehicle transportation were highly and negatively correlated (r = −0.66, p<.001).

Demographics

Parents responded to questions on their age, marital status, education level, income, employment status, race/ethnicity, and length of residence in the U.S. All variables were closed-ended items with the exception of age and length of residence in the U.S. which were open-ended. Covariates included education, employment status and income and were recoded into dichotomous variables.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable to determine their appropriate use in these analyses. Correlations were run to assess collinearity between the acculturation measures and findings suggest that the measures were moderately correlated. The highest correlation observed was between country of origin and acculturation score (r = .53, p<.001) and the lowest correlation was between dyads by country of origin and child’s language use (r = .32, p<.001). Parent’s BMI, income, employment status, education and child’s gender were tested as potential covariates of acculturation. Income, employment status and education were significant confounders, thus they were included as covariates in all analyses. Child’s gender was a significant covariate when acculturation was defined as the child’s preferred language with family. Four separate Analysis of Covariance Models [ANCOVAs] were used to examine the relationship between each measure of acculturation and child’s transportation to and from school. Post hoc analyses, using Scheffe tests to control for Type I error given cell size differences, were used to examine pairwise comparisons. All statistics were performed using SAS 9.0 (2002: SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA)

RESULTS

Models 1–4 were adjusted for income, employment status, and education. Similar results were found for analyses with and without fathers (n=23); therefore analyses with fathers are reported.

Walking to and from School (See Table 2)

Table 2.

Analysis of Covariance+ examining school transportation among Latino children from kindergarten through 2nd grade and their parents (N=800). San Diego, California, 2004–2007.

| COUNTRY OF ORIGIN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | Mexican-born | Mixed status | U.S.-born | F-value | p-value |

| Walk to/from school | 5.0AB | 4.0A | 3.7B | 2.91 | 0.05 |

| Drive to/from school | 4.9CD | 5.9C | 6.2D | 3.08 | 0.05 |

| CHILD'S PRIMARY LANGUAGE USED WITH FAMILY | |||||

| Spanish* | Bilingual | English | F-value | p-value | |

| Walk to/from school | |||||

| Female child | 3.8 | 3.6A | 5.5A | 4.62 | 0.01 |

| Male child | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 1.34 | 0.26 |

| Drive to/from school | 5.8 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 2.75 | 0.06 |

| PARENTS’ YEARS LIVING IN THE U.S. | |||||

| <12 yrs | >=12yrs | F-value | p-value | ||

| Walk to/from school | 4.61 | 3.65 | 9.01 | 0.003 | |

| Drive to/from school | 5.3 | 6.3 | 9.66 | 0.001 | |

| ARSMA II SCALE | |||||

| Very Mexican oriented | Bicultural | Slightly Anglo oriented | F-value | p-value | |

| Walk to/from school | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 1.37 | 0.25 |

| Drive to/from school | 5.7 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 1.25 | 0.29 |

Reference group;

Significant at p< 0.05;

Adjusted for education, employment and income. Number of trips to/from school during a school week ranged from 1 to 10.

Model 1: Parent-Child Dyads by Country of Origin

Significant differences were observed by country of origin for walking to and from school (F=7.71, df= 5, 732, p<.001; see Figure 1). Parent-child dyads who were both Mexican-born reported walking to and from school more often than mixed status and U.S.-born dyads. Pairwise difference between mixed-status and U.S.-born dyads was not significant.

Figure 1.

Model 2: Child’s Primary Language Use with Family

Figure 2 illustrates a significant interaction between child’s language use and gender on walking to school. English-dominant females walked to and from school more frequently than bilingual females (F=7.81, df= 4, 364, p<.0001).

Figure 2.

Model 3: Parent’s Number of Years Living in the U.S

Significant differences were observed for parent’s years in the U.S. on walking to and from school (F=10.82, df= 4, 737, p<.001 see Figure 1). Parents living in the U.S. less than twelve years had children who walked to/from school more frequently than children with parents who had been U.S. residents for 12 years or more.

Model 4: ARSMA-II

The relationship between parent acculturation score and walking to school was not significant (see Figure 1). However, there was a trend consistent with previous results suggesting less walking to and from school among more acculturated parents.

Vehicle Transportation (See Table 2)

Model 1: Parent and Child Dyads by Country of Origin

Significant differences were observed by country of origin on vehicle transportation (F=8.32, df= 5, 732, p<.001; see Figure 1). Mexican-born parent-child dyads both reported driving to school less often than mixed status and U.S.-born dyads. Pairwise difference between mixed-status and U.S.-born dyads was not significant.

Model 2: Child’s Primary Language Use with Family

The relationship between language use and vehicle transportation was not significant.

Model 3: Parent’s Number of Years Living in the U.S

Significant differences were observed by parent’s years in the U.S. on vehicle transportation (F=11.68, df= 4, 737, p<.001; see Figure 1). Parents living in the U.S. for greater than 12 years had children who used vehicle transportation to and from school more often than children of parents living in the U.S. for less than 12 years.

Model 4: ARSMA-II

The relationship between parent acculturation score and vehicle transportation was not significant but there was a trend consistent with previous results suggesting more vehicle transportation among more acculturated parents (see Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The current study illustrated that Latino children use active transportation as a form of moderate PA and suggested a relationship between acculturation and active school commute. Two findings point to the protective effects of being less acculturated. Mexican-born parent-child dyads and parents who had lived in the U.S. for less than twelve years reported more walking for school commute by their child. These results are conceptually equivalent to adult studies observing that active transportation was more likely among Latinos compared to whites (Berrigan et al., 2006b). The findings for child’s language preference indicated that English-dominant girls were more likely to walk to and from school compared to bilingual girls. Similarly, another study showed greater inactivity among Spanish-dominant versus English-dominant Latino-Americans (Berrigan et al., 2006a). Conversely, in this study, the language preference of the boys was not significantly associated with active school commute. These findings are supported by Saksvig et al. (Saksvig et al., 2007) who found that girls engage in more walking for school commute than boys in the U.S. population. We speculate that more acculturated English-dominant girls come from families of higher socioeconomic status; therefore may live in safe and walkable neighborhoods. Lastly, parents’ acculturation score was not associated with child’s walking to and from school. In sum, various quantifications of acculturation resulted in different conclusions regarding the relationship between walking for school commute and acculturation. These findings highlight a need for greater specificity of measuring acculturation before reliable conclusions can be drawn about the influence of culture on health behaviors.

This study has several limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional; therefore causality cannot be inferred. Similar to another study (Saksvig et al., 2007), the distance from school to home was not determined and may be a confounder because school neighborhoods are dense with apartment complexes. Given that the children were in kindergarten, child’s PA and acculturation were based on parent-report, rather than self-report or an objective measure. The parent sample consisted of mostly females; therefore conclusions are limited to mothers. Nevertheless, strengths of this study included a large sample size and the first to report on the relationship between various measures of acculturation and walking to school by Latino children.

CONCLUSION

Although studies describe Latinos as sedentary (Crespo et al., 2001), the current study found that less acculturated children were more likely to walk to school than more acculturated children. Active transportation has been noted among less acculturated adults (Berrigan et al., 2006b) and the results of the present study support this finding. Because walking is common in Mexico, it would be expected that Mexican parents had children who walked more often than children of U.S.-born parents. Given that economic parity is not expected in less acculturated individuals (Mendoza & Dixon, 1999), limited access to an automobile or increased gas prices, may have made active school commute more attractive.

Obesity rates are escalating (Jolliffe, 2004; Ogden et al., 2006), especially among Latinos (Mendoza & Dixon, 1999; Popkin & Udry, 1998), and opportunities to increase PA are needed. The importance of active transportation among Latino children cannot be understated given the increasing number of immigrants (Zhou, 1997). Walking for school commute is an economically simple way to increase MVPA among children (Oja et al., 1998; Tudor-Locke et al., 2001). PA interventions should aim to increase and/or maintain walking to school among less acculturated children, and promote active school commute as an easy and inexpensive form of MVPA for more acculturated Latinos (Oja et al., 1998).

Acknowledgements

The study, Aventuras para Niños, was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R01HL073776). Additional support was provided by the San Diego Prevention Research Center (U48 DP00036-03). Special thanks are extended to the SDSU Minority Biomedical Research Scientist (MBRS) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1 R25 GM58906-08), and to Nadia Campbell and Noe Crespo for all their support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen ML, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Diamant AL, Hambarsoomian K, Schuster MA. Adolescent participation in preventive health behaviors, physical activity, and nutrition: Differences across immigrant generations for Asians and Latinos compared with whites. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(2):337–343. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala GX, Elder JP, Campbell NR, Roy N, Slymen DJ, Engelberg M, et al. Correlates of body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio among Mexican women in the United States: Implications for intervention development. Women’s Health Issues. 2004;14(5):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrigan D, Dodd K, Troiano R, Reeve B, Ballard-Barbash R. Physical activity and acculturation among adult Hispanics in the United States. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2006a;77(2):147–157. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrigan D, Troiano RP, McNeel T, DiSogra C, Ballard-Barbash R. Active transportation increases adherence to activity recommendations. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine. 2006b;31(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. In: Acculturation and parent-child relationships: Measurement and development. Bornstein M, Cote L, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal SC, Hanson CE, Romero AJ, Coyle KK. Behavioural risk factors and protective factors in adolescents: A comparison of Latinos and non-Latino whites. Ethnicity & Health. 2002;7(3):181–193. doi: 10.1080/1355785022000042015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Guidelines for school and community programs to promote lifelong physical activity among young people. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1998;46:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AR, Andersen LB, Wedderkopp N, Page AS, Froberg K. Physical activity levels of children who walk, cycle, or are driven to school. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(3):179. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo C, Smit E, Carter-Pokras O, Andersen R. Acculturation and leisure-time physical inactivity in Mexican American adults: Results from NHANES III 1988–1994. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(8):1254–1257. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(3):275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Harris LC, Jasso R. An acculturation scale for Mexican-American normal and clinical populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1980;2(199–217) [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Campbell NR, Litrownik AJ, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Parra-Medina D, et al. Predictors of cigarette and alcohol susceptibility and use among Hispanic migrant adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:115–123. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the U.S.: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(11):2023. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, McMurray RG, Popkin BM. Adolescent physical activity and inactivity vary by ethnicity: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1999;135(3):301. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe D. Extent of overweight among us children and adolescents from 1971 to 2000. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:4–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin B, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable E. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, McAuley E. Gender and acculturation influences on physical activity in Latino adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31(2):138–144. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza F, Dixon L. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. In: Hernandez D, editor. Children of immigrants: Health, adjustment and public assistance. Board on children, youth and families. (Vol. Committee on the Health and Adjustment of Immigrant Children and Families.) Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman S, Castro C, Albright C, King A. Comparing acculturation models in evaluating dietary habits among low-income Hispanic women. Ethnicity & Disease. 2004;14(3):399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States 1999–2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oja P, Vuori I, Paronen O. Daily walking and cycling to work: Their utility as health-enhancing physical activity. Patient Education and Counseling. 1998;33(S1):S87. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Udry JR. Adolescent obesity increases significantly in second and third generation U.S. Immigrants: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of Nutrition. 1998;128(4):701–706. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksvig BI, Catellier DJ, Pfeiffer K, Schmitz KH, Conway T, Going S, et al. Travel by walking before and after school and physical activity among adolescent girls. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(2):153–158. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Ainsworth BE, Popkin BM. Active commuting to school - an overlooked source of childrens' physical activity? Sports Medicine. 2001;31(5):309–313. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Reynolds K, Shakib S, Spruijt-Metz D, Sun P, Johnson CA. Acculturation, physical activity, and fast-food consumption among Asian-American and Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Community Health. 2004;29(6):467. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-3395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; Travel and environmental implications of school sitting. 2003

- Zhou M. Growing up American: The challenge confronting immigrant children and children of immigrants. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:63–95. [Google Scholar]