Abstract

A serological diagnostic test using phenolic glycolipid-I (PGL-I) developed in the 1980s is commercially available, but the method is still inefficient in detecting all forms of leprosy. Therefore, more-specific and -reliable serological methods have been sought. We have characterized major membrane protein II (MMP-II) as a candidate protein for a new serological antigen. In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the MMP-II antigen (MMP-II ELISA) for detecting antibodies in leprosy patients and patients' contacts in the mid-region of Vietnam and compared to the results to those for the PGL-I method (PGL-I ELISA). The results showed that 85% of multibacillary patients and 48% of paucibacillary patients were positive by MMP-II ELISA. Comparison between the serological tests showed that positivity rates for leprosy patients were higher with MMP-II ELISA than with PGL-I ELISA. Household contacts (HHCs) showed low positivity rates, but medical staff members showed comparatively high positivity rates, with MMP-II ELISA. Furthermore, monitoring of results for leprosy patients and HHCs showed that MMP-II is a better index marker than PGL-I. Overall, the epidemiological study conducted in Vietnam suggests that serological testing with MMP-II would be beneficial in detecting leprosy.

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae infection, which sometimes leads to progressive peripheral nerve injury and systematic deformity (16, 30). Early detection of M. leprae infection and early start of treatment are key in avoiding deformities. Also, in order to decrease the incidence of new cases, it is important to find and treat the sources of the infection as soon as possible. Thus, early detection of these infected individuals who cannot be clinically diagnosed is critical (34). The diagnosis of leprosy is based on microscopic detection of acid-fast bacilli in skin smears or biopsies, along with clinical and histopathological evaluation of suspected patients. Recently, diagnostic methods for leprosy based on M. leprae DNA sequences have been developed (10, 20, 25). However, it is difficult to use these methods in developing countries which still have leprosy hot spot areas, because such methods require expensive machines and materials as well as skilled technicians. Although many developing countries have recently established laboratories for DNA-based diagnosis, it is harder to perform DNA tests than serodiagnostic tests. Thus, in countries where leprosy is endemic, diagnosis still relies on clinical observations and easy, inexpensive tests.

Serodiagnosis is generally accepted as the easiest way of diagnosing a disease. For leprosy serodiagnosis, the only antigen currently used is phenolic glycolipid I (PGL-I), which is supposedly specific to M. leprae (21, 26, 27). Since the identification of PGL-I in 1981 by Hunter and Brennan (14), a number of serological tools have been developed. Simple assays, such as the Serodia-Leprae method, a dipstick assay, and lateral flow tests based on the PGL-I antigen, have been used to detect leprosy patients in areas where leprosy is endemic (3, 15, 17, 32). However, these tests seem to be insufficient for detection of both multibacillary (MB) and paucibacillary (PB) patients, as well as for early diagnosis, and have not been used as widely as would be expected in field situations (6, 29). Therefore, we have begun the search for a more sensitive antigen. Major membrane protein II (MMP-II; encoded by the ML2038c gene, named bfrA, also known as bacterioferritin) was previously identified from the cell membrane fraction of M. leprae as an antigenic molecule capable of activating both antigen-presenting cells and T cells (19, 24). A homology search of the mycobacteria nucleotide database revealed that MMP-II is conserved between M. leprae, M. tuberculosis, and M. avium. The amino acid identity is about 86% among the three species. However, we have previously examined the role of MMP-II in the humoral responses of Japanese patients and showed that MMP-II could contribute to the specific serodetection of leprosy patients (18).

In the present study, we performed a serological test using serum samples collected in regions of leprosy endemicity in Vietnam and evaluated the use of MMP-II as an antigen for serodiagnosis of leprosy. We believe that identifying the appropriate antigens for serodiagnosis could facilitate the development of simple diagnostic tests, like dip-stick assays, for use in developing countries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples.

A total of 974 serum samples from various individuals, including in- and out-patients of Quyhoa National Leprosy & Dermato-Venereology Hospital (NDH), were obtained under informed consent. The sera were donated by 205 leprosy patients (163 patients undergoing treatment and 42 new patients), 428 household contacts (HHCs), 130 medical staff members, and 211 noncontact healthy individuals. Sera of leprosy patients and their contacts were taken at regional medical centers in the midregion of Vietnam, including those in the Danang, Quangnam, Quangngai, Binhdinh, Phuyen, Khanhhoa, Ninhthuan, Gialai, Kontum, Daklak, and Daknong provinces, where the average prevalence rate is 0.17 (number of cases/10,000 persons) and the average detection rate is 2.13 (number of cases/10,000 persons). Among these provinces, Binhdinh, Ninhthuan, Gialai, and Kontum had hot spot areas. The medical staff members consisted of workers in Quyhoa NDH, including medical doctors, nurses, pharmacists, technicians, and helpers. Only the sera from medical staff members who were not HHCs of leprosy patients were used in this study. Sera were also obtained from healthy persons living in the Binhdinh province (n = 126) and the Longan province (n = 85), which are distantly located from each other. Out of 205 leprosy patients, 121 had MB leprosy and 84 had PB leprosy. We made the initial diagnosis according to the Ridley-Jopling classification system and classified patients as MB and PB types based on the WHO recommendation. In Vietnam, the M. bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination against tuberculosis has been undertaken in earnest since 1976. Almost all medical staff personnel who donated their blood for this study were vaccinated with BCG.

MMP-II and PGL-I antigens.

The MMP-II gene (ML2038c, or bfrA) was expressed in Escherichia coli as a fusion construct by using a pMAL-c2X expression vector (New England BioLabs) (18). Synthetic bovine serum albumin-conjugated trisaccharide-phenyl propionate for the detection of PGL-I antibodies was produced by our laboratory. The procedure for synthesis of the antigen is described elsewhere (12).

ELISAs for detection of antibodies.

MaxiSorp (Nalge Nunc) microtiter plates were coated with 50 μl antigen solution (MMP-II [0.4 μg/ml] and PGL-I [0.2 μg/ml]) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) and kept at 4°C overnight. The optimal concentrations of these antigens were determined in advance. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol was performed as described previously (18). We measured anti-MMP-II immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and anti-PGL-I IgM antibodies. Plate-to-plate variations in optical density (OD) readings were controlled for by using a common standard serum.

Monitoring.

One hundred forty-eight leprosy patients have been monitored using MMP-II ELISA and PGL-I ELISA during their multidrug therapy (MDT) treatment since 2001. Twelve-month MDT for MB was carried out, and sampling was performed three to five times. Also, HHCs were monitored once every 3 or 6 months by both the MMP-II and the PGL-I ELISA methods from 2001 to 2004.

Statistics.

The data were analyzed using a statistical software package (version 9.3.2.0; MedCalc software). A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn to calculate the cutoff levels (2). Additionally, the statistically significant differences between assays were confirmed by the chi-square test (28).

RESULTS

Comparison of the distribution of ELISA values between MMP-II and PGL-I.

We focused on the distribution of ELISA values derived from MB leprosy patients and compared them to those from healthy individuals (Fig. 1). The cutoff OD405 value for anti-MMP-II antibody was defined as 0.103 (95% confidence interval, 85.2 to 93.7), and that for anti-PGL-I antibody was defined as 0.452 (95% CI, 85.2 to 93.7), by ROC curve analysis (MedCalc software) using OD titers from 211 healthy individuals and 205 leprosy patients. The distribution pattern of MMP-II ELISA values was quite different from that of PGL-I ELISA for healthy individuals. While the OD values of most healthy individuals were in the low range for MMP-II ELISA (Fig. 1A), the titers obtained by PGL-I ELISA showed a bell-shaped curve which was similar to that of MB leprosy patients (Fig. 1B). The PGL-I ELISA values for PB leprosy patients also showed a similar bell-shaped curve (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of distributions of OD values in MB leprosy patients and normal individuals. (A) Distribution pattern of MMP-II ELISA values in patients and healthy individuals. (B) Distribution pattern of PGL-I ELISA values in patients and healthy individuals. The solid squares show the number of MB leprosy patients in each OD value range, and the open squares show the number of healthy individuals.

Detection rate of antibodies in sera of leprosy patients.

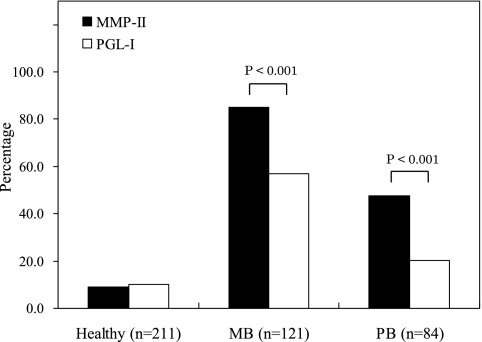

Among the MB patients, 85.1% were positive by MMP-II ELISA and 57.0% were positive by PGL-I ELISA; 47.6% of PB patients were positive by MMP-II ELISA, and 20.2% were positive by PGL-I ELISA (Fig. 2). The MMP-II ELISA values for both MB and PB patients were significantly higher than the PGL-I ELISA values (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Patients undergoing treatment and new cases showed a similar difference (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of positivity rates of patients as determined by MMP-II and PGL-I ELISA. Black bars show percentages of healthy individuals and patients positive by MMP-II ELISA, and white bars show those for PGL-I ELISA. Statistically significant differences were confirmed by the chi-square test and are indicated as P values.

Seropositivity rates of contacts, medical staff members, and healthy volunteers.

There was no significant difference in positivity rate between MMP-II ELISA and PGL-I ELISA for healthy individuals and HHCs (Fig. 3). Also, there was no significant difference in positivity rate between MMP-II ELISA and PGL-I ELISA for healthy individuals from different provinces, namely, Binhdinh and Longan (data not shown). In contrast, the medical staff showed a significantly higher rate of positivity by MMP-II ELISA (26.2%) than by PGL-I ELISA. The anti-MMP-II antibody positivity rate for the medical staff was significantly higher than those for healthy individuals and HHCs.

FIG. 3.

Positivity rates of HHCs and medical staff members as determined by MMP-II and PGL-I ELISA. Black bars show percentages of HHCs and medical staff members positive by MMP-II ELISA, and white bars show those by PGL-I ELISA. Statistically significant differences were confirmed by the chi-square test and are indicated as P values.

Monitoring of HHCs.

Previous studies suggested the usefulness of PGL-I ELISA in monitoring the effects of leprosy treatment (5, 8, 9, 22). Therefore, we monitored anti-MMP-II antibody titers in patients after treatment and compared them to anti-PGL-I antibody titers. Ninety-two MB and 56 PB patients were monitored. The anti-MMP-II antibody value of approximately 30% of monitored MB patients declined within 1 to 2 years after the start of treatment, in accordance with changes in bacterial index values (data not shown), although approximately 50% of MB patients showed no reduction in ELISA values and 20% of patients showed mild increases in value. Three representative samples of MB patients are shown in Fig. 4. Among PB patients, 18% of the monitored patients had reduced anti-MMP-II antibody titers. On the other hand, anti-PGL-I antibody titers were reduced approximately only 20% in both MB and PB patients during the monitoring period. Therefore, anti-MMP II antibody may reflect the efficacy of treatment similarly to or slightly better than anti-PGL-I antibody in some cases. Furthermore, 9 individuals out of 428 HHCs developed leprosy after several years of monitoring. Among the nine cases, two individuals had increasing antibody titers by MMP-II and/or PGL-I ELISA 1 year before manifesting clinical symptoms (data not shown). Patient HHC192 showed a prominent rise in anti-MMP-II antibody values during the asymptomatic period. Both patients developed MB leprosy. The other seven, whose antibody levels did not show an apparent increase during the observation period, developed PB leprosy.

FIG. 4.

Monitoring of three MB leprosy patients by MMP-II and PGL-I ELISAs. Three cases of monitored leprosy patients are shown. The closed circles show MMP-II ELISA values, and the open circles show PGL-I ELISA values. Note that the cutoff value for MMP-II is 0.103 and that of PGL-I is 0.452.

DISCUSSION

Serodiagnosis is the easiest, cheapest, and least invasive diagnostic tool for infectious diseases. Currently, PGL-I is used as a specific antigen for M. leprae, but in practice, its sensitivity and specificity are not as high as expected, even though previous studies using stock sera reported that the detection rate for MB patients was more than 80% (1, 3, 4, 7). The present study involving Vietnamese leprosy patients indicated that there is a significant difference between MMP-II ELISA and PGL-I ELISA in detecting both MB and PB leprosy. The positivity rate of anti-MMP-II antibody for MB leprosy was approximately 85%, and that for PB leprosy was 48%; these titers were significantly higher than the titers obtained by PGL-I ELISA (57% and 20%, respectively). The detection rates obtained by MMP-II ELISA were similar to those for a previous study using stock sera from Japanese leprosy patients (18). However, the positivity rates of anti-PGL-I antibody in the present study were significantly lower than those for the Japanese patients, although the same antigens for both MMP-II and PGL-I were used in the two studies.

There are several possible reasons why the sensitivity of PGL-I ELISA was low in the present study. One reason may be that some healthy Vietnamese individuals have high anti-PGL-I antibody titers. Although we could not conduct further detailed analysis on the subjects, these individuals might be highly exposed to M. leprae, and so their B lymphocytes might be repeatedly stimulated with M. leprae-derived antigens, including PGL-I. It seems quite difficult to discriminate the healthy individuals from MB or PB leprosy patients by PGL-I ELISA, as shown in Fig. 1. Furthermore, we concluded that a reasonable cutoff point for PGL-I ELISA was an OD405 of 0.452, as deduced from Fig. 1 and the ROC values, but this resulted in lower sensitivity. The difference in sensitivity between PGL-I ELISA and MMP-II ELISA may also be due to differences in the biochemical features of the antigens. PGL-I is a glycolipid component, and as such, it might be retained in some infected cells for a long time after the initial exposure (13, 33). This speculation is supported by previous reports showing that healthy individuals residing in areas where leprosy is endemic had high anti-PGL-I antibody titers, and M. leprae DNA was recovered by PCR from the nasal swabs of these individuals (31, 32). Also, it has been reported that the usefulness of PGL-I-based tests for early diagnosis is limited, since 7 to 10% of individuals testing positive do not develop the disease (14).

In contrast, MMP-II is a protein antigen and is considered to be one of the immunodominant antigens of M. leprae (19). Therefore, in individuals who have been exposed to M. leprae but have not developed leprosy, antigen-presenting cells expressing MMP-II might feasibly be eliminated from the body by immune cells such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes and thus lack the ability to produce anti-MMP-II antibodies through antigen-presenting-cell-dependent mechanisms. These speculations seem to be supported by our present observations with sera from patients monitored over time. Anti-MMP-II antibody titers of MB patients declined earlier than PGL-I titers with MDT treatment, indicating the disappearance of MMP-II antigens, while no apparent reduction in PGL-I antigens was observed during the 12 months of observation (Fig. 4). Furthermore, in one case the anti-MMP-II antibody titer increased drastically before manifestation of clinically apparent leprosy (data not shown).

Medical staff members (n = 130) showed a high positivity rate by MMP-II ELISA, compared with healthy individuals or HHCs. These medical staff members were mostly BCG vaccinated, as were the HHCs. Therefore, it seems that BCG vaccination has no effect on anti-MMP-II antibody titers. Although we could not determine a conclusive reason for the high positivity rate, these medical personnel may be repeatedly exposed to M. leprae in hospitals. However, we cannot eliminate the possibility that they have produced the antibody in response to exposure to other mycobacteria, since the MMP-II protein is conserved in other pathogenic mycobacterial species, such as M. tuberculosis and M. avium, though the staff members with high anti-MMP-II antibody titers did not manifest any clinical signs or features indicating infection with other mycobacteria. We tried to perform nested PCR using the M. leprae-specific repetitive element for DNA extracted from nasal swabs of some hospital staff members (n = 25). However, because the sampling dates for the serological test and the PCR test were not coordinated, we could not come to a definite conclusion. Nevertheless, we were surprised to find that ≅40% (n = 25) of the nasal swab samples were positive (data not shown). As for tuberculosis, it is said that one-third of the world population is infected with M. tuberculosis. The same may be the case with leprosy, although further studies are needed with larger populations, including medical staff members as well as contacts and noncontacts of leprosy.

Taken together, our data indicate that MMP-II ELISA could be useful as a supporting serodiagnostic tool in combination with other clinical diagnostic methods and may also be useful in monitoring disease activity. Furthermore, in this study the correlation between MMP-II and PGL-I was low, with a correlation coefficient among the 205 leprosy patients of only 0.63. If both PGL-I and MMP-II antibodies could be measured simultaneously, the sensitivity of the assay system could be increased. Considering that PGL-I is a sugar antigen (eliciting IgM antibodies) and MMP-II is a protein antigen (eliciting IgG antibodies), assaying for a combination of these antibodies could lead to more-accurate detection of leprosy in the field.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Health Sciences research grants for research on emerging and reemerging infectious diseases; by an international cooperation research grant (topic code 18C4) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; and by Quyhoa NDH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agis, F., P. Schlich, J. L. Cartel, C. Guidi, and M. A. Bach. 1988. Use of anti-M. leprae phenolic glycolipid-I antibody detection for early diagnosis and prognosis of leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 56:527-535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck, J. R., and E. K. Schultz. 1986. The use of relative operating characteristic (ROC) curves in test performance evaluation. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 110:13-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bührer-Sékula, S., H. L. Smits, G. C. Gussenhoven, J. van Leeuwen, S. Amador, T. Fujiwara, P. R. Klatser, and L. Oskam. 2003. Simple and fast lateral flow test for classification of leprosy patients and identification of contacts with high risk of developing leprosy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1991-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartel, J. L., S. Chanteau, J. P. Boutin, R. Plichart, P. Richez, J. F. Roux, and J. H. Grosset. 1990. Assessment of anti-phenolic glycolipid-I IgM levels using an ELISA for detection of M. leprae infection in populations of the South Pacific Islands. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 58:512-517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chanteau, S., J. L. Cartel, P. Celerier, R. Plichart, S. Desforges, and J. Roux. 1989. PGL-I antigen and antibody detection in leprosy patients: evolution under chemotherapy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 57:735-743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanteau, S., P. Glaziou, C. Plichart, P. Luquiaud, R. Plichart, J. F. Faucher, and J. L. Cartel. 1993. Low predictive value of PGL-I serology for the early diagnosis of leprosy in family contacts: results of a 10-year prospective field study in French Polynesia. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 61:533-541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi, V., S. Sinha, B. K. Girdhar, and U. Sengupta. 1991. On the value of sequential serology with a Mycobacterium leprae-specific antibody competition ELISA in monitoring leprosy chemotherapy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 59:32-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho, S. N., R. V. Cellona, T. T. Fajardo, Jr., R. M. Abalos, E. C. dela Cruz, G. P. Walsh, J. D. Kim, and P. J. Brennan. 1991. Detection of phenolic glycolipid-I antigen and antibody in sera from new and relapsed lepromatous patients treated with various drug regimens. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 59:25-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, S. N., R. V. Cellona, L. G. Villahermosa, T. T. Fajardo, Jr., M. V. Balagon, R. M. Abalos, E. V. Tan, G. P. Walsh, J. D. Kim, and P. J. Brennan. 2001. Detection of phenolic glycolipid I of Mycobacterium leprae in sera from leprosy patients before and after start of multidrug therapy. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:138-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donoghue, H. D., J. Holton, and M. Spigelman. 2001. PCR primers that can detect low levels of Mycobacterium leprae DNA. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:177-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reference deleted.

- 12.Fujiwara, T., S. W. Hunter, S. N. Cho, G. O. Aspinall, and P. J. Brennan. 1984. Chemical synthesis and serology of disaccharides and trisaccharides of phenolic glycolipid antigens from the leprosy bacillus and preparation of a disaccharide protein conjugate for serodiagnosis of leprosy. Infect. Immun. 43:245-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelber, R. H., F. Li, S. N. Cho, S. Byrd, K. Rajagopalan, and P. J. Brennan. 1989. Serum antibodies to defined carbohydrate antigens during the course of treated leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 57:744-751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter, S. W., and P. J. Brennan. 1981. A novel phenolic glycolipid from Mycobacterium leprae possibly involved in immunogenicity and pathogenicity. J. Bacteriol. 147:728-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izumi, S., T. Fujiwara, M. Ikeda, Y. Nishimura, K. Sugiyama, and K. Kawatsu. 1990. Novel gelatin particle agglutination test for serodiagnosis of leprosy in the field. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:525-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Job, C. K. 1989. Nerve damage in leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 57:532-539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kai, M., Y. Maeda, S. Maeda, Y. Fukutomi, K. Kobayashi, Y. Kashiwabara, M. Makino, M. A. Abbasi, M. Z. Khan, and P. A. Shah. 2004. Active surveillance of leprosy contacts in country with low prevalence rate. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 72:50-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda, Y., T. Mukai, M. Kai, Y. Fukutomi, H. Nomaguchi, C. Abe, K. Kobayashi, S. Kitada, R. Maekura, I. Yano, N. Ishii, T. Mori, and M. Makino. 2007. Evaluation of major membrane protein-II as a tool for serodiagnosis of leprosy. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 272:202-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda, Y., T. Mukai, J. Spencer, and M. Makino. 2005. Identification of an immunomodulating agent from Mycobacterium leprae. Infect. Immun. 73:2744-2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez, A. N., C. F. P. C. Britto, J. A. C. Nery, E. P. Sampaio, M. R. Jardim, E. N. Sarno, and M. O. Moraes. 2006. Evaluation of real-time and conventional PCR targeting complex 85 genes for detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA in skin biopsy samples from patients diagnosed with leprosy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3154-3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meeker, H. C., W. R. Levis, E. Sersen, G. Schuller-Levis, P. J. Brennan, and T. M. Buchanan. 1986. ELISA detection of IgM antibodies against phenolic glycolipid-I in the management of leprosy: a comparison between laboratories. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 54:530-539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meeker, H. C., G. Schuller-Levis, F. Fusco, M. A. Giardina-Becket, E. Sersen, and W. R. Levis. 1990. Sequential monitoring of leprosy patients with serum antibody levels to phenolic glycolipid-I, a synthetic analog of phenolic glycolipid-I, and mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 58:503-511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reference deleted.

- 24.Pessolani, M. C., D. R. Smith, B. Rivoire, J. McCormick, S. A. Hefta, S. T. Cole, and P. J. Brennan. 1994. Purification, characterization, gene sequence, and significance of a bacterioferritin from Mycobacterium leprae. J. Exp. Med. 180:319-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phetsuksiri, B., J. Rudeeaneksin, P. Supapkul, S. Wachapong, K. Mahotarn, and P. J. Brennan. 2006. A simplified reverse transcriptase PCR for rapid detection of Mycobacterium leprae in skin specimens. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 48:319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuring, R. P., F. J. Moet, D. Pahan, J. H. Richardus, and L. Oskam. 2006. Association between anti-PGL-I IgM and clinical and demographic parameters in leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 77:343-355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekar, B., R. N. Sharma, G. Leelabai, D. Anandan, B. Vasanthi, G. Yusuff, M. Subramanian, and M. Jayasheela. 1993. Serological response of leprosy patients to Mycobacterium leprae specific and mycobacteria specific antigens: possibility of using these assays in combinations. Lepr. Rev. 64:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel, S., and N. J. Castellan, Jr. 1988. Non-parametric statistics for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edition. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

- 29.Soebono, H., and P. R. Klatser. 1991. A seroepidemiological study of leprosy in high- and low-endemic Indonesian villages. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 59:416-425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoner, G. L. 1979. Importance of the neural predilection of Mycobacterium leprae in leprosy. Lancet ii(8150):994-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beers, S., M. Hatta, and P. R. Klatser. 1999. Seroprevalence rates of antibodies to phenolic glycolipid-I among school children as an indicator of leprosy endemicity. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 67:243-249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Beers, S., S. Izumi, B. Madjid, Y. Maeda, R. Day, and P. R. Klatser. 1994. An epidemiological study of leprosy infection by serology and polymerase chain reaction. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 62:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhagen, C., W. Faber, P. Klatser, A. Buffing, B. Naafs, and P. Das. 1999. Immunohistological analysis of in situ expression of mycobacterial antigens in skin lesions of leprosy patients across the histopathological spectrum. Association of Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan (LAM) and Mycobacterium leprae phenolic glycolipid-I (PGL-I) with leprosy reactions. Am. J. Pathol. 154:1793-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. 2007. Global leprosy situation. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 82:225-232.17585406 [Google Scholar]