Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the GAL genes encode the enzymes required for galactose metabolism. Regulation of these genes has served as the paradigm for eukaryotic transcriptional control over the last 50 years. The switch between inert and active gene expression is dependent upon three proteins—the transcriptional activator Gal4p, the inhibitor Gal80p, and the ligand sensor Gal3p. Here, we present a detailed spatial analysis of the three GAL regulatory proteins produced from their native genomic loci. Using a novel application of photobleaching, we demonstrate, for the first time, that the Gal3p ligand sensor enters the nucleus of yeast cells in the presence of galactose. Additionally, using Förster resonance energy transfer, we show that the interaction between Gal3p and Gal80p occurs throughout the yeast cell. Taken together, these data challenge existing models for the cellular localization of the regulatory proteins during the induction of GAL gene expression by galactose and suggest a mechanism for the induction of the GAL genes in which galactose-bound Gal3p moves from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to interact with the transcriptional inhibitor Gal80p.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae GAL genes encode the enzymes of the Leloir pathway that are required to catalyze the conversion of galactose into a more metabolically useful version, glucose-6-phosphate (12, 14, 16, 23-25). When yeast cells are grown in the absence of galactose, the GAL genes are largely transcriptionally inert. If, however, the cells are switched into a medium in which galactose is the only available carbon source, then the GAL genes are rapidly transcribed and the mRNA accumulates to a high level (34). Galactose is a comparatively poor sugar source for the cell, and yeast will metabolize other sources of carbon (e.g., glucose) in preference to galactose, even if a mixture of glucose and galactose is available to them (5). Glucose triggers catabolite repression of the GAL genes, and the expression of the activator upon which they depend, the Zn(II)2Cys6 protein Gal4p, is severely reduced (11). In the presence of other carbon sources, such as raffinose or glycerol, Gal4p is produced in the cell and can be found tethered upstream of the GAL genes. Under these conditions, the activity of DNA-bound Gal4p is inhibited by its interaction with another protein, Gal80p (22). Although the presence of galactose within the cell triggers the activation of Gal4p, neither Gal4p nor Gal80p functions as the galactose sensor. Instead, a transcriptional inducer or ligand sensor, Gal3p, interacts with the transcriptional inhibitor, Gal80p, in a galactose- and ATP-dependent manner (35). Although Gal3p shares a high degree of sequence similarity with the yeast galactokinase Gal1p, it does not itself possess a galactokinase activity (32). Instead, Gal3p seems to require galactose and ATP so that it can adopt a conformation to enable it to interact with Gal80p (25). The net result of this interaction is that Gal4p becomes active and transcription of the GAL genes proceeds.

The molecular mechanism by which the activation of the yeast GAL genes occurs has been the subject of a great deal of debate. Some reports have suggested that induction occurs through the association of a tripartite complex formed between Gal4p, Gal80p, and Gal3p (22). Others have, however, proposed that Gal80p dissociates from Gal4p and interacts with Gal3p in the cytoplasm of yeast cells (20), thereby freeing Gal4p from the inhibitory effects of Gal80p and allowing transcriptional activation to occur (21). Biochemical and genetic evidence has been used to support both potential models for GAL gene activation. In favor of the nuclear association of Gal4p, Gal3p, and Gal80p are the observations that Gal4p purified from yeast grown in the presence and absence of galactose is associated with Gal80p (19), artificially constructed Gal80p molecules that contain an activation domain are able to regulate transcription in the presence and absence of galactose (15), and the observation, using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis, that Gal4p and Gal80p do not dissociate from each other (4). The dissociation model is supported by data indicating that Gal3p is predominately cytoplasmic (20) and that the expression of a myristoylated version of the protein (which will be targeted to the cell plasma membrane) does not unduly impair the induction of the GAL genes (21). In addition, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments (21) and pull-down assays (28) suggest that the Gal4p-Gal80p complex is somewhat weakened (although perhaps not completely dissociated) when cells are grown in the presence of galactose.

The regulation of yeast GAL gene expression is sensitive to the relative levels of each of the regulatory proteins (Gal3p, Gal4p, and Gal80p). For example, the overproduction of Gal3p results in the galactose-independent expression of the GAL genes (3), and the overproduction of Gal80p can suppress this constitutive expression (31). Therefore, to determine the localization of each of the GAL regulatory proteins in both the uninduced and induced states, we strove to produce tagged versions of each of these proteins from their native genomic loci. This approach has allowed us to determine that both Gal80p and Gal3p are present in the nucleus and cytoplasm of galactose-grown cells and that the interaction between the two occurs in both cellular compartments. Our data thus support a model for GAL gene induction in which Gal3p interacts with galactose in the cytoplasm, which then translocates to the nucleus. An interaction with Gal80p then occurs, and the Gal3p-Gal80p complex can subsequently be found both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm of cells. These challenge existing models for GAL gene expression and provide further understanding of the molecular mechanism of this exquisitely elegant genetic switch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth media.

All yeast strains were derived from S. cerevisiae FY23 (2). C-terminal fusions of a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) variant (YPet) or a cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) variant (CFP4) (17) with Gal3p, Gal80p, and Gal4p used a PCR-mediated replacement strategy as described previously (26). For higher-level expression of GAL80-YFP, a genomic DNA fragment including 1 kbp of DNA upstream of the GAL80 gene, the YFP fusion, and 1 kbp downstream of the GAL80 stop codon was cloned into the 2μm-based vector YEplac195 (10) to generate the plasmid pG80Y. Yeast were grown in synthetic complete liquid medium consisting of 6.7 g liter−1 yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (Formedium) and 0.72 g liter−1 complete amino acid mix (27). Galactose or raffinose was added as sole carbon source to a final concentration of 2% (wt/vol). Growth conditions were 30°C for 16 h with constant agitation. For immobilizing yeast for microscopy, 15 μl culture was pipetted onto a Superfrost Plus glass slide (Menzel-Glaser) and left for 3 min and then excess liquid was replaced with 4 μl growth medium over which a 22-mm by 22-mm coverslip was placed.

Microscopy.

High-resolution epifluorescence microscopy was carried out on a Leica DMR microscope equipped with an HCX PL APO 100× oil (numerical aperture, 1.4 to 0.7) objective (part no. 506220; Leica Microsystems, United Kingdom) fitted with differential interference contrast optics and a SPOT Xplorer 4MP charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Image Solutions, United Kingdom). The gain on the camera was set to 16×. Electron-multiplying CCD (EMCCD) imaging was carried out on a Leica DM5500 microscope fitted with a Photometrics Cascade II camera (Photometrics, United Kingdom), a 100× oil objective, and a Leica EL6000 external light source. Gain was set to 1×, multiplication gain was set to 4,045, and binning was set to 1×1. For all EMCCD images, two exposures were taken in quick succession and then averaged. YPet was visualized using a YFP filter set (part no. 41028; Chroma Technology Corp., Rockingham, VT), and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining of yeast nuclei was visualized using the “A” filter set (Leica Microsystems). For YPet/CFP4 ratio comparisons the multiplication gain on the EMCCD camera was set to 3,795 and a 3-pixel-radius Gaussian blur was applied to each image. Using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), a circular region of interest was highlighted that encompassed most of the yeast cell. Average intensity values were calculated for the YPet and CFP4 channels. Average background values were also calculated for each channel. The YPet/CFP4 ratio for each yeast cell was calculated using the formula (YPet − background)/(CFP4 − background).

Cytoplasmic bleaching.

Bleaching studies used a Leica TCS SP5 upright confocal microscope equipped with a 63× (numerical aperture, 1.4) oil objective. The argon laser was set at 50%. For YFP, the 514-nm laser line was used at 15% power for acquisition and the 488-, 496-, and 514-nm lines were used at 100% for bleaching. For green fluorescent protein (GFP), the 488-nm laser line was used for acquisition and the 488-, 476-, and 458-nm lines were used for bleaching. Scanning speed was 400 Hz, zoom was set at 4×, frame accumulation was set to 2, capture size was 512 × 128 pixels, and the pinhole was set to 2.826 Airy units. For bleaching, a small square region of interest was drawn at the edge of a yeast cell and 100 images were captured at 710-ms intervals. DAPI was visualized using a multiphoton laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA). Figure 2 shows representative images of a series of bleaching experiments carried out on the Gal80p-YFP strain (n = 8 bleach experiments) and the Gal3p-YFP strain (n = 10).

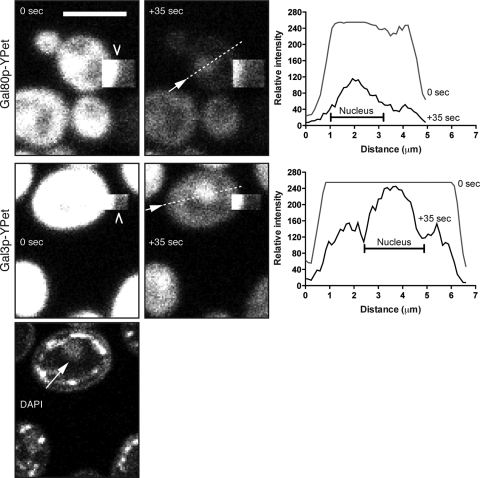

FIG. 2.

Cytoplasmic bleaching of Gal80p-YPet and Gal3p-YPet grown in galactose. Shown are images at 0 s and +35 s for both fusions. The bleached area is a square box (barbed arrowhead) that borders the yeast cell. For Gal3p-YPet, the DAPI channel is included and shows the position of the nucleus (arrow). The graphs show profile plots at 0 s and at +35 s of a line taken through the cell at the positions shown in the +35-s images (dashed line and arrow). Bars = 5 μm.

FRET analysis.

FRET studies were carried out on the EMCCD imaging system. Custom filter sets for donor (d436/10x, 455dclp, d480/40m), acceptor (hq500/20x, q515lp, hq535/30m), and FRET (d436/10x, 455dclp, hq535/30m) were constructed by Chroma Technology Corp. Light source power for the EL6000 light source was set to minimum. Light source power on the DM5500 microscope was set to minimum (FRET), +2 (acceptor), and maximum (donor). For the FRET positive control, light source power was minimum (FRET), +1 (acceptor), and +2 (donor). Images were acquired in the order acceptor, FRET, and then donor. Binning was set to 2 × 2, and two 450-ms exposures were acquired in rapid succession and averaged for each channel. Data analysis was carried out using the PixFRET plug-in of ImageJ (7). A Gaussian blur of 1.2-pixel radius was used in the determination for spectral bleed-through models. No Gaussian blur was applied to the FRET images, and the threshold correction factor was set to 1.1.

RESULTS

Cellular localization of Gal3p, Gal4p, and Gal80p when expressed from their native loci.

To rigorously examine the cellular localization of the three proteins constituting the yeast GAL genetic switch, the native genomic locus of the gene encoding each protein was tagged at its 3′ end with DNA encoding a variant of either the YFP or the CFP. The particular variants chosen were YPet and CFP4, as these have previously been shown to exhibit enhanced FRET (17). Gene tagging at the 3′ end has previously been used to create fusion proteins that have minimal impact on the expression levels or activity of the encoded protein (13). Indeed, the tagged strains showed equal growth rates in medium containing galactose as the sole sugar source, indicating that GAL induction was not impaired by the tagging process (data not shown).

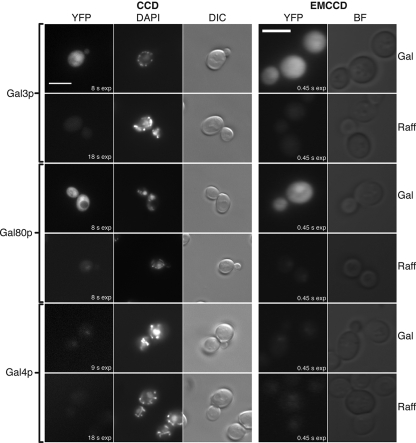

Imaging of the YFP fusion proteins was carried out with identical optics using either a high-resolution CCD camera or an EMCCD camera (Fig. 1). EMCCD exposure times used to obtain suitable images were 0.45 s, whereas CCD exposures were in the range of 8 to 18 s. This indicates that EMCCD technology is particularly suited to viewing the YFP fusion proteins. When yeast cells were grown in the presence of a sugar source that does not induce GAL gene expression (raffinose), the levels of the galactose ligand sensor, Gal3p-YFP, were found to be too low for detection by either type of camera system (Fig. 1, Gal3p and raffinose). Under the same conditions Gal80p-YFP is observed in the nucleus of cells (Fig. 1, Gal80p and raffinose), consistent with its function of binding the Gal4p transcriptional activator. In the presence of raffinose, Gal4p-YFP yielded a very low nuclear signal which was only just detectable using the EMCCD system (Fig. 1, Gal4p and raffinose). Under inducing conditions, in the presence of galactose, Gal4p-YFP remained in the nucleus (Fig. 1, Gal4p and Gal) whereas both Gal80p-YFP and Gal3p-YFP yielded a comparatively stronger signal throughout the cell. For Gal80p-YFP, the signal appears to originate from both the cytoplasm and nucleus, as visualized along with DAPI staining with the CCD camera system. In the case of Gal3p-YFP, any fluorescence signal originating from the nucleus is difficult to distinguish from the high signal originating from the cytoplasm. However, the part of the cell occupied by the nucleus was not found to be devoid of Gal3p-YFP (Fig. 1, Gal3p and Gal).

FIG. 1.

Suitability and comparison of CCD versus EMCCD technologies for imaging fluorescent protein fusions to components of the GAL genetic switch. C-terminal YFP fusions of Gal3p, Gal80p, and Gal4p were grown in either galactose (Gal) or raffinose (Raff). Images were taken with a CCD or EMCCD camera. Exposure times for EMCCD YFP acquisitions were 0.45 s. Exposure times for the CCD YFP acquisitions are shown in the figure. Gal4p-YFP (Gal/Raff) CCD images and Gal4p-YFP (Raff) EMCCD images were further contrast enhanced after acquisition. Bars = 5 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast; BF, bright field.

Determining the level of GAL regulatory proteins in induced cells.

Proper induction of the GAL genes in the presence of galactose requires the inhibitor Gal80p to be deactivated or sequestered by the ligand sensor Gal3p. Previously it has been reported that, in glucose-containing media, there are 166 molecules of Gal4p, 721 molecules of Gal3p, and 784 molecules of Gal80p in each yeast cell (8). This is consistent with our own observations that, in the absence of galactose, Gal4p is present in the cell at a very low level (Fig. 1, Gal4p and raffinose). Using the fluorescently labeled proteins, we have determined the relative amounts of Gal3p and Gal80p within yeast cells that are grown in galactose-containing medium. Yeast strains containing GAL3-YFP and GAL80-CFP or GAL3-CFP and GAL80-YFP were constructed. The YFP/CFP ratios for individual yeast cells were determined. Using the YFP-tagged Gal3p and CFP-tagged Gal80p, we observed relatively more YFP fluorescence than CFP fluorescence—a YFP/CFP ratio of 1.17 ± 0.19 (n = 67). Conversely, using YFP-tagged Gal80p and CFP-tagged Gal3p, we observed relatively more CFP fluorescence than YFP fluorescence—a YFP/CFP ratio of 0.64 ± 0.11 (n = 73). These data suggest that there is an excess of Gal3p in the cell compared to Gal80p, under these conditions, and that this difference is approximately 1.3-fold.

Bleaching Gal3p or Gal80p fluorescence in the cytoplasm leaves a stable nuclear signal.

To confirm the dual nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of Gal80p-YFP in galactose, confocal microscopy was used to specifically bleach part of a cell that was occupied only by the cytoplasm. The rationale for this experiment was that cytoplasmic streaming would result in the cytoplasmic YFP pool passing beneath the bleached region, resulting in the accelerated disappearance of YFP in the cytoplasm compared to that of any YFP found within the nucleus or other neighboring cells. This approach allows us to specifically study the nucleus without the complications of a high YFP signal emanating from the surrounding cytoplasm. The bleached area was generated where the edge of the area was placed toward the edge of the yeast cell (Fig. 2, Gal80p and 0 s). The free diffusion and cytoplasmic mixing of Gal80p-YFP within the cytoplasm resulted in the rapid depletion of the cytoplasmic Gal80p-YFP pool (see movie S1 in the supplemental material). After 35 s of bleaching, the cytoplasmic YFP signal had disappeared, leaving a significant nuclear signal representing nucleus-localized Gal80p-YFP (Fig. 2, Gal80p and +35 s). In contrast, the YFP signal in cells which had not undergone cytoplasmic bleaching was diminished after 35 s, but this general acquisition bleaching, due to repeated scans by the confocal laser, was observed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus and failed to generate a specific localization signal. Similar results were obtained using the Gal3p-YFP yeast strain (Fig. 2, Gal3p and 0 and +35 s; see also movie S2 in the supplemental material). That is, a significant proportion of Gal3p is excluded from the cytoplasm and is located in a region that corresponds to the nucleus as indicated by DAPI staining (Fig. 2, DAPI). As a control for the cytoplasmic bleaching process, we tagged the SUP45 gene with the coding sequence for YPet. Sup45p functions as a translational release factor, eRF1 (30). It binds to Sup35p (eRF3) to form the translational release factor complex that is found exclusively in the cytoplasm (13). SUP45 is an essential gene (9), which means that a viable strain produced following YFP tagging must contain a functional version of the protein. As shown in movie S3 in the supplemental material, bleaching the cytoplasm of the Sup45p-YFP strain resulted in a comparatively uniform loss of signal and did not yield a bright area corresponding to the nucleus following the bleaching process.

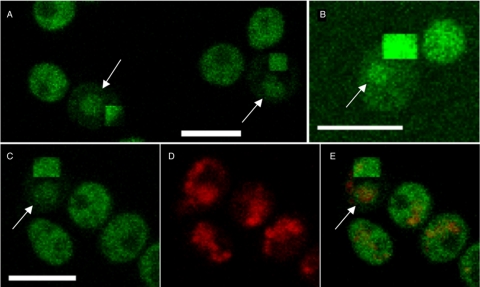

Gal3p localization in living cells has been previously visualized using a fusion with enhanced GFP (EGFP) (21). Cytoplasmic bleaching of Gal3p-EGFP (Fig. 3) yields results essentially identical to those for Gal3p-YFP (Fig. 2). The nuclear localization of Gal3p-EGFP is not due to the prolonged growth of the yeast in galactose medium, as the same localization is observed in cells 45 min after transfer from a raffinose- to a galactose-supplemented medium (Fig. 3B). We therefore conclude that a significant fraction of both Gal3p and Gal80p is retained in the nucleus of a yeast cell when the GAL genes are being expressed.

FIG. 3.

Gal3p-GFP localizes to the nucleus and cytoplasm. Gal3p-GFP was constructed as part of the whole-genome GFP-tagging project (13). (A) Removal of the cytoplasmic signal by bleaching shows nuclear-localized Gal3p-GFP as indicated by the arrows. (B) Gal3p is observed in the nucleus shortly after transfer to a galactose-containing medium. Gal3p-GFP was grown overnight in raffinose and transferred to fresh medium containing galactose and incubated for 45 min. The arrow indicates the nuclear-localized Gal3p. (C, D, E) Cytoplasmic bleaching reveals nuclear Gal3p-GFP. Gal3p-GFP is shown in panel C, DAPI in panel D, and the merged image in panel E. The persistence of nuclear GFP signal in the bleached cell is shown by the arrow in panels C and E. Bars = 5 μm.

Cellular location of the interaction between Gal3p and Gal80p in induced cells.

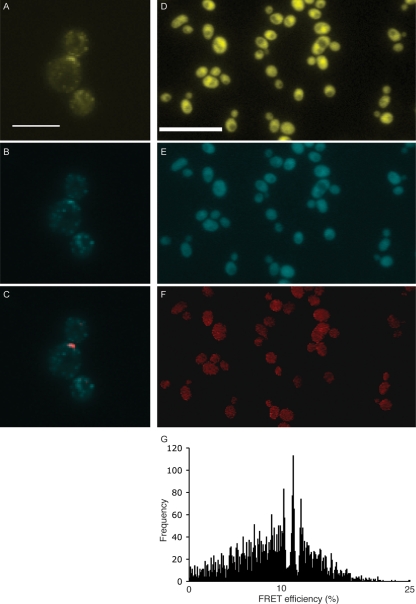

Since both Gal3p and Gal80p are in the nucleus and cytoplasm of galactose-grown yeast cells, we set out to ask where within the cell the interaction between the two occurs. Using FRET, any interactions that result between tagged proteins can be detected and localized. FRET detection was optimized for the CFP-YFP donor-acceptor pair by using Abp1p-CFP and Sla1p-YFP. These two fusions localize to actin patches within the cell cortex and have previously been shown to yield a FRET signal for a subset of these patches that contain both Abp1p and Sla1p (33). Using the EMCCD camera system, FRET was observed for several patches (Fig. 4A to C), which demonstrates the suitability of the imaging system. Yeast strains producing both YFP and CFP versions of the various GAL regulatory proteins were constructed. Figure 4 shows images of a strain producing Gal3p-YFP and Gal80p-CFP. The localization of both proteins tagged in this way (Fig. 4D and E) is identical to that observed in yeast strains in which either Gal3p or Gal80p is tagged alone (Fig. 1). Figure 4F shows that the FRET signal that occurs between these two proteins was observed throughout the cell. A FRET signal should occur only if the GFP tags on Gal3p and Gal80p are separated by less than 60 to 70 Å (6). The FRET efficiency has a mean of 9.6%, and the mode, represented by the central peak in Fig. 4G, is 11.6%. This is comparable to efficiencies recorded for other protein interactions in S. cerevisiae such as the Fet3p-Ftr1p high-affinity iron permease complex (13%) (29) and Ste12p oligomerization (18%) (18).

FIG. 4.

Detection of FRET between Gal3p and Gal80p. (A to C) FRET positive controls Sla1p-YFP (A), Abp1p-CFP (B), and PixFRET output (red) merged with Abp1p-CFP (C). A FRET signal is observed at an actin patch near the bud neck. (D) Gal3p-YPet. Bar = 10 μm. (E) Gal80p-CFP. (F) PixFRET output. (G) Histogram showing frequencies of FRET efficiencies. The total number of FRET-positive pixels was 4,167, and the mean FRET efficiency was 9.6%.

We have not been able to reproduce the FRET previously reported between Gal4p and Gal80p in the absence of galactose (4). In raffinose, we have shown Gal4p-YFP to be barely detectable, which is in contrast to Gal80p-YFP under the same growth conditions (Fig. 1). This suggests that Gal4p is present within the nucleus at very low levels, as previously reported (8), and that an equimolar interaction with Gal80p would make even the most efficient FRET signals difficult to detect.

The observations that (i) Gal80p is confined to the nucleus in the absence of galactose (Fig. 1), (ii) Gal80p and Gal3p are both nuclear and cytoplasmic in the presence of galactose, and (iii) a Gal80p-Gal3p interaction is detected throughout the cell suggest that galactose sensing, and possibly direct interaction with galactose-bound Gal3p, has a role in defining the cytoplasmic location of Gal80p. Disrupting the galactose-sensing mechanism through the deletion of both GAL1 and GAL3 was found to result in Gal80p being largely confined to the nucleus, regardless of the presence of galactose in the growth medium (Fig. 5). Overexpression of the GAL80-YFP fusion in this same background (Fig. 5, pG80Y) resulted in a high YFP signal emanating from both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. However, under these conditions, Gal80-YFP was found to exhibit significant enrichment in the nucleus.

FIG. 5.

Gal80p-YFP is concentrated in the nucleus in Δgal1 Δgal3 cells grown in the presence of galactose. Gal80p-YFP localization in the wild-type background is shown for comparison. Also shown are gal1Δ gal3Δ cells carrying the Gal80-YFP fusion construct on a high-copy-number vector (pG80Y). The presence of pG80Y results in a significant increase in the YFP signal, and short exposures are displayed (insets). Bar = 5 μm. Raff, raffinose; WT, wild type; DIC, differential interference contrast.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the cellular location of the yeast GAL regulatory proteins is an important step to elucidating both the precise molecular mechanism by which the presence of galactose is sensed by the cell and the mechanism by which this event is relayed to the transcriptional machinery. Apparently contradictory mechanisms for these processes have been suggested for the induction of the GAL genes in S. cerevisiae (20-22) and in the related milk yeast Kluyveromyces lactis (1). In an effort to reconcile these mechanisms, we genomically tagged each of the genes encoding the GAL regulatory proteins with a variant of the GFP. This ensured that each of these proteins was produced at a level as natural as possible. In the absence of galactose, the production of these proteins was difficult to detect even using highly sensitive microscopy techniques (Fig. 1). In the presence of galactose, however, the visualization of both Gal3p and Gal80p became quite obvious. In keeping with previous reports (20, 21), Gal80p was found to be located within both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of induced yeast cells. However, a similar localization pattern was also observed for Gal3p, indicating that Gal3p was also located in both cellular compartments.

Using cytoplasmic bleaching methods (Fig. 2 and 3), we have been able to confirm that, in addition to their presence in the cytoplasm, both Gal80p and Gal3p are found within the nucleus of cells that are actively expressing the GAL genes. Finally, using FRET, we have been able to show that Gal3p and Gal80p associate with each other throughout the cells of galactose-grown yeast (Fig. 4F). The FRET experiments have the advantage that they not only identify the location of Gal3p and Gal80p in galactose-induced yeast cells but they also indicate the site of interaction between the two proteins. The transfer of resonance energy between the YFP and CFP fluorophore tags occurs only if the proteins are physically separated by less than ∼70 Å (6). This separation distance is unlikely to occur efficiently due to random collisions, since both Gal3p and Gal80p are expressed at relatively low levels (8). Therefore, the FRET data represent the real sites of interaction between Gal3p and Gal80p. That is, Gal3p and Gal80p interact in a galactose-dependent fashion within both the nucleus and cytoplasm of yeast cells.

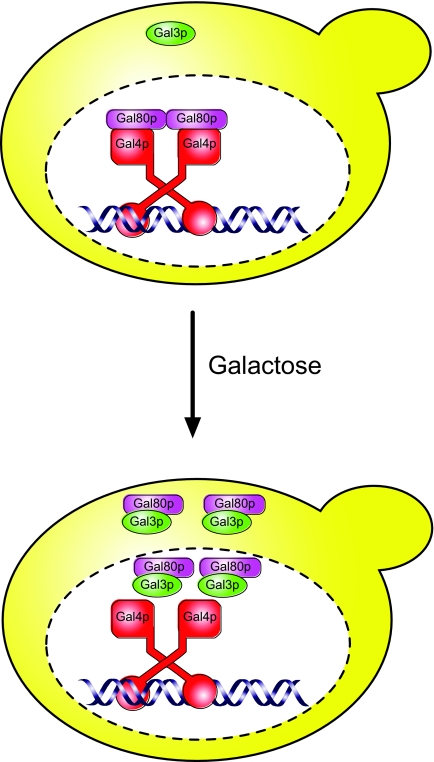

A model summarizing our and other data from S. cerevisiae is shown in Fig. 6. In the absence of galactose, Gal4p resides in the nucleus, where it is tethered to DNA upstream of the GAL genes. Gal80p is associated with Gal4p and is also located within the nucleus. A small level of Gal3p is present in the cell under these circumstances, but it is not nucleus localized. Upon the switch to galactose, the levels of both Gal3p and Gal80p increase. We suggest that Gal3p binds to galactose (and ATP) in the cytoplasm and that the galactose-bound form of Gal3p enters the nucleus, where it associates with Gal80p. In addition, the Gal3p-Gal80p complex can exit the nucleus and remain associated in the cytoplasm, which is in contrast to observations in the related yeast Kluyveromyces lactis, where GAL gene activation proceeds via a mechanism that does not involve the translocation of Gal80p into the cytoplasm (1). In our S. cerevisiae model, a fraction of the Gal3p-Gal80p complex remains in the nucleus, although presumably in a form that does not impinge upon the transcriptional activity of Gal4p. The nuclear localization of Gal3p means that the formation of a tripartite complex existing between Gal4p, Gal80p, and Gal3p (22), even if it occurs only transiently, cannot be ruled out. The data presented here clearly demonstrate that Gal3p is not solely confined to the cytoplasm of S. cerevisiae cells which are actively expressing the GAL genes. Rather, it would appear to be the dynamic interplay between nuclear and cytoplasmic forms of the Gal3p-Gal80p complex that is responsible for the induction of the GAL genes.

FIG. 6.

Model of regulation of GAL gene expression. In the absence of galactose, Gal80p tightly binds and inhibits the Gal4p transcriptional activator. Upon induction, galactose enters the cell and binds to Gal3p in the cytoplasm, permitting the entry of Gal3p into the nucleus. Gal80p dissociation from Gal4p, either partial or complete, is coupled with Gal3p binding and results in the activation of GAL gene expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the BBSRC and Wellcome Trust.

We thank Kathryn Ayscough (University of Sheffield, United Kingdom) for providing the Sla1p-YFP and Abp1p-CFP yeast strains and Gillian Dalgliesh and Amanda Hughes for help with construction of some of the strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 October 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders, A., H. Lilie, K. Franke, L. Kapp, J. Stelling, E. D. Gilles, and K. D. Breunig. 2006. The galactose switch in Kluyveromyces lactis depends on nuclear competition between Gal4 and Gal1 for Gal80 binding. J. Biol. Chem. 28129337-29348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barberis, A., J. Pearlberg, N. Simkovich, S. Farrell, P. Reinagel, C. Bamdad, G. Sigal, and M. Ptashne. 1995. Contact with a component of the polymerase II holoenzyme suffices for gene activation. Cell 81359-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat, P. J., and J. E. Hopper. 1992. Overproduction of the GAL1 or GAL3 protein causes galactose-independent activation of the GAL4 protein: evidence for a new model of induction for the yeast GAL/MEL regulon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 122701-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhaumik, S. R., T. Raha, D. P. Aiello, and M. R. Green. 2004. In vivo target of a transcriptional activator revealed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Genes Dev. 18333-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broach, J. R. 1979. Galactose regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The enzymes encoded by the GAL7, 10, 1 cluster are co-ordinately controlled and separately translated. J. Mol. Biol. 13141-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, T. N., and E. G. D. Muller. 2007. Measuring the proximity of proteins in living cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer between CFP and YFP. Methods Microbiol. 36269-280. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feige, J. N., D. Sage, W. Wahli, B. Desvergne, and L. Gelman. 2005. PixFRET, an ImageJ plug-in for FRET calculation that can accommodate variations in spectral bleed-throughs. Microsc. Res. Tech. 6851-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaemmaghami, S., W. K. Huh, K. Bower, R. W. Howson, A. Belle, N. Dephoure, E. K. O'Shea, and J. S. Weissman. 2003. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425737-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giaever, G., A. M. Chu, L. Ni, C. Connelly, L. Riles, S. Veronneau, S. Dow, A. Lucau-Danila, K. Anderson, B. Andre, A. P. Arkin, A. Astromoff, M. El-Bakkoury, R. Bangham, R. Benito, S. Brachat, S. Campanaro, M. Curtiss, K. Davis, A. Deutschbauer, K. D. Entian, P. Flaherty, F. Foury, D. J. Garfinkel, M. Gerstein, D. Gotte, U. Guldener, J. H. Hegemann, S. Hempel, Z. Herman, D. F. Jaramillo, D. E. Kelly, S. L. Kelly, P. Kotter, D. LaBonte, D. C. Lamb, N. Lan, H. Liang, H. Liao, L. Liu, C. Luo, M. Lussier, R. Mao, P. Menard, S. L. Ooi, J. L. Revuelta, C. J. Roberts, M. Rose, P. Ross-Macdonald, B. Scherens, G. Schimmack, B. Shafer, D. D. Shoemaker, S. Sookhai-Mahadeo, R. K. Storms, J. N. Strathern, G. Valle, M. Voet, G. Volckaert, C. Y. Wang, T. R. Ward, J. Wilhelmy, E. A. Winzeler, Y. Yang, G. Yen, E. Youngman, K. Yu, H. Bussey, J. D. Boeke, M. Snyder, P. Philippsen, R. W. Davis, and M. Johnston. 2002. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418387-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugino. 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griggs, D. W., and M. Johnston. 1991. Regulated expression of the GAL4 activator gene in yeast provides a sensitive genetic switch for glucose repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 888597-8601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holden, H. M., I. Rayment, and J. B. Thoden. 2003. Structure and function of enzymes of the Leloir pathway for galactose metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 27843885-43888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huh, W. K., J. V. Falvo, L. C. Gerke, A. S. Carroll, R. W. Howson, J. S. Weissman, and E. K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425686-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston, M. 1987. A model fungal gene regulatory mechanism: the GAL genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 51458-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leuther, K. K., and S. A. Johnston. 1992. Nondissociation of GAL4 and GAL80 in vivo after galactose induction. Science 2561333-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohr, D., P. Venkov, and J. Zlantanova. 1995. Transcriptional regulation in the yeast GAL gene family: a complex genetic network. FASEB J. 9777-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen, A. W., and P. S. Daugherty. 2005. Evolutionary optimization of fluorescent proteins for intracellular FRET. Nat. Biotechnol. 23355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overton, M. C., and K. J. Blumer. 2000. G-protein-coupled receptors function as oligomers in vivo. Curr. Biol. 10341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parthun, M. R., and J. A. Jaehning. 1992. A transcriptionally active form of GAL4 is phosphorylated and associated with GAL80. Mol. Cell. Biol. 124981-4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng, G., and J. E. Hopper. 2000. Evidence for Gal3p's cytoplasmic location and Gal80p's dual cytoplasmic-nuclear location implicates new mechanisms for controlling Gal4p activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 205140-5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng, G., and J. E. Hopper. 2002. Gene activation by interaction of an inhibitor with a cytoplasmic signaling protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 998548-8553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platt, A., and R. J. Reece. 1998. The yeast galactose genetic switch is mediated by the formation of a Gal4p/Gal80p/Gal3p complex. EMBO J. 174086-4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reece, R. J. 2000. Molecular basis of nutrient controlled gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 571161-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubio-Texeira, M. 2005. A comparative analysis of the GAL genetic switch between not-so-distant cousins: Saccharomyces cerevisiae versus Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Res. 51115-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sellick, C. A., and R. J. Reece. 2005. Eukaryotic transcription factors as direct nutrient sensors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30405-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheff, M. A., and K. S. Thorn. 2004. Optimized cassettes for fluorescent protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 21661-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman, F. 1991. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1943-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sil, A. K., S. Alam, P. Xin, L. Ma, M. Morgan, C. M. Lebo, M. P. Woods, and J. E. Hopper. 1999. The Gal3p-Gal80p-Gal4p transcription switch of yeast: Gal3p destabilizes the Gal80p-Gal4p complex in response to galactose and ATP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 197828-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh, A., S. Severance, N. Kaur, W. Wiltsie, and D. J. Kosman. 2006. Assembly, activation, and trafficking of the Fet3p.Ftr1p high affinity iron permease complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 28113355-13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stansfield, I., K. M. Jones, V. V. Kushnirov, A. R. Dagkesamanskaya, A. I. Poznyakovski, S. V. Paushkin, C. R. Nierras, B. S. Cox, M. D. Ter-Avanesyan, and M. F. Tuite. 1995. The products of the SUP45 (eRF1) and SUP35 genes interact to mediate translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 144365-4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki-Fujimoto, T., M. Fukuma, K.-I. Yano, H. Sakurai, A. Vonika, S. A. Johnston, and T. Fukasawa. 1996. Analysis of the galactose signal transduction pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Interaction between Gal3p and Gal80p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 162504-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Timson, D. J., and R. J. Reece. 2002. Kinetic analysis of yeast galactokinase: implications for transcriptional activation of the GAL genes. Biochimie 84265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren, D. T., P. D. Andrews, C. W. Gourlay, and K. R. Ayscough. 2002. Sla1p couples the yeast endocytic machinery to proteins regulating actin dynamics. J. Cell Sci. 1151703-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yarger, J. G., H. O. Halvorson, and J. E. Hopper. 1984. Regulation of galactokinase (GAL1) enzyme accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 61173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zenke, F. T., R. Engles, V. Vollenbroich, J. Meyer, C. P. Hollenberg, and K. D. Breunig. 1996. Activation of Gal4p by galactose-dependent interaction of galactokinase and Gal80p. Science 2721662-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.