Abstract

PML, a nuclear protein, interacts with several transcription factors and their coactivators, such as HIPK2 and p300, resulting in the activation of transcription. Although PML is thought to achieve transcription activation by stabilizing the transcription factor complex, little is known about the underlying molecular mechanism. To clarify the role of PML in transcription regulation, we purified the PML complex and identified Fbxo3 (Fbx3), Skp1, and Cullin1 as novel components of this complex. Fbx3 formed SCFFbx3 ubiquitin ligase and promoted the degradation of HIPK2 and p300 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. PML inhibited this degradation through a mechanism that unexpectedly did not involve inhibition of the ubiquitination of HIPK2. PML, Fbx3, and HIPK2 synergistically activated p53-induced transcription. Our findings suggest that PML stabilizes the transcription factor complex by protecting HIPK2 and p300 from SCFFbx3-induced degradation until transcription is completed. In contrast, the leukemia-associated fusion PML-RARα induced the degradation of HIPK2. We discuss the roles of PML and PML-retinoic acid receptor α, as well as those of HIPK2 and p300 ubiquitination, in transcriptional regulation and leukemogenesis.

In human leukemia, specific chromosomal translocations result in the expression of specific fusion proteins and malignancy (16, 39). The PML gene is the target of the t(15;17) chromosome translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) and is fused to the retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) gene, which leads to the generation of a PML-RARα fusion protein (11, 12, 18, 28). The PML protein is known to localize in discrete nuclear speckles called PML nuclear bodies (NBs) (58). In the NBs, PML interacts with several transcription factors such as p53 and AML1, transcription coactivators such as HIPK2 and p300, and apoptosis modulators such as pRB and DAXX (27, 52, 53). PML enhances p53-dependent apoptosis by inducing p53 target genes (15, 20). Additionally, PML can lead to cell senescence by activating p53 (46). We have reported that PML interacts with AML1, a target of several chromosome translocations in leukemia (41), and stimulates the AML1-dependent differentiation of murine myeloid progenitor cells (44). APL-derived PML-RARα is thought to be dominant negative to PML. PML-RARα disrupts NBs into microspeckles (14) and inhibits DNA damage-induced apoptosis (56) and PML IV enhancement of PU.1-induced myeloid differentiation (57). Thus, PML activates and PML-RARα represses transcription. However, little is known about how PML activates transcription. Moreover, it remains unclear why transcription factors and coactivators are localized in NBs.

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway involves two successive steps: labeling of the substrates with multiple ubiquitin molecules and degradation of the labeled substrates at the 26S proteasome. Ubiquitin conjugation is catalyzed by three enzymes: the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, and the ubiquitin-protein ligase E3 (17). E3 ubiquitin ligases are classified into several types, including HECT-type E3, RING finger motif-containing E3, and U-box domain containing E3. MDM2, the APC/C complex, and the SCF complex are known to be the RING finger motif-containing E3 (21, 33, 54). The SCF complex is composed of F-box protein, Skp1, Cullin1 (Cul1), and ROC1. In the SCF complex, F-box proteins recognize specific substrates for ubiquitination. Therefore, the different SCF complexes are designated according to their F-box proteins (7, 24, 30). Proteins ubiquitinated by the SCF complex are degraded rapidly by the proteasome.

In this study, we purified the PML complex to clarify the role of PML in transcription and identified Fbxo3 (Fbx3), Skp1, and Cul1 as components of the PML complex. We found that Fbx3, whose substrates were unknown, formed SCFFbx3 ubiquitin ligase and regulated the degradation of HIPK2 and p300 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. This degradation was inhibited by PML through a mechanism that did not involve the inhibition of ubiquitination. PML, HIPK2, and Fbx3 increased p53 transcriptional activity synergistically. Our data suggest that the interplay between SCFFbx3-induced ubiquitination and degradation of transcription coactivators, such as HIPK2 and p300, and the stabilization of these coactivators by PML play critical roles in transcriptional regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, infection, and antibodies.

K562 cells, MOLT-4 cells, H1299 cells, MCF7 cells, and NB4 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). SKNO-1 cells were cultured in GIT (Wako). BOSC23 cells and PLAT-E cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FCS. NIH 3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% calf serum. Mouse bone marrow (BM) cell suspensions were prepared by flushing isolated femora with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the cells were cultured in StemPro-34 supplemented with 2.5% nutrient supplement, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 ng/ml interleukin-3, 50 ng/ml SCF, 10 ng/ml oncostatin M, 20 ng/ml interleukin-6, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.1% tylosin. For the production of retroviruses, PLAT-E cells were transfected with pMSCV-derived retroviruses by the calcium phosphate precipitation method, and culture supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection. NIH 3T3 cells were infected by incubation in the culture supernatant of PLAT-E cells transfectants for 24 h.

Anti-HIPK2 antibody was described previously (26). Anti-Fbx3 antibody was generated by immunizing mice with glutathione S-transferase-tagged Fbx3. Other antibodies were purchased commercially and were as follows: antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) (3F10; Roche), anti-FLAG (M2; Sigma), anti-Gal4 (RK5C1; Santa Cruz), anti-p300 (N15; Santa Cruz), antitubulin (H235; Santa Cruz), antiubiquitin (FK2; Nippon Bio-Test), and anti-PML (001 [MBL], H238 [Santa Cruz], or 36.1-104 [UBI]).

Plasmids.

Human Fbx3 cDNA was amplified by PCR from a human cDNA library generated from poly(A)+ RNA of K562 cells by use of the oligonucleotides 5′-ACCGGGCCAGGCAAGATGGC-3′ as the upstream primer and 5′-GCAAACCCAAACAATCCAATTCC-3′ as the downstream primer. The N-terminal FLAG tag and HA tag were fused to Fbx3 cDNAs by use of the oligonucleotide 5′-ACGTACCGCGGACCATGGCAGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGGCGGCCATGGAGACCGAGAC-3′ or 5′-ACGTACCGCGGACCATGGCATACCCATACGACGTGCCTGACTACGCTGCGGCCATGGAGACCGAGAC-3′ as the upstream primer and 5′-TCTGCGCTTCCACAGCATCG-3′ as the downstream primer in the PCR. Fbx3 deletion mutants were generated by PCR using pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 or pcDNA-FLAG-Fbx3 as the template. The PML, AML1, p300, and HIPK2 expression vectors were generated as described previously (1, 32, 37, 44, 57). p53 expression vectors and the MDM2-luc reporter were kindly provided by Y. Taya.

Purification of the PML complex.

K562 cells were transfected with pLNCX or pLNCX-FLAG-PML I by electroporation. Cells stably expressing FLAG-PML I protein were cloned. The cells (∼1 × 1010 cells) were lysed by sonication at 4°C in 500 ml of 500 mM NaCl lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) supplemented with Complete (Roche). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and incubated with 2.5 ml of anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (M2)-conjugated beads with rotation at 4°C for 12 h. The beads with absorbed PML I immunocomplexes were washed six times with 50 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 250 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF). The PML I complexes were selectively eluted by incubating twice with 0.2 mg/ml FLAG peptide in 7.5 ml of lysis buffer for 2 h. The eluates were concentrated using a filtration device and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, excised, destained with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 50% acetonitrile, dried, digested with sequence-grade modified trypsin in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), extracted with 5% trifluoroacetic acid-50% acetonitrile, and subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

BOSC23 cells were transfected with the desired vectors. After 15 h, culture supernatants were exchanged for fresh media and cells were treated with or without 10 μM MG132 (Calbiochem) for 9 h. The cells were lysed by incubation at 4°C for 30 min in lysis buffer. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and the supernatants were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads with rotation at 4°C for 12 h. The beads were washed six times with 1 ml of lysis buffer. After being washed, the cell extracts were selectively eluted by incubating with 0.2 mg/ml FLAG peptide for 2 h.

Cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were fractionated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies and with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immune complexes were visualized by the ECL or ECL-Plus technique (Amersham).

RNA interference, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR.

Fbx3-specific and control small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were purchased from Ambion. RARα-specific and control stealth siRNAs were purchased from Invitrogen. MOLT-4 cells and NB4 cells were transfected with these siRNAs by using Nucleofector (Amaxa). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected five times with these siRNAs by use of Lipofectamine 2000. For reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), total RNA was purified using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNAs were transcribed using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen). PCRs were performed using the following primers: Fbx3 (human) forward (5′-GGTGTCCTCGGATGGTTTTATCTC-3′) and reverse (5′-TCTCTGATGATGGGGAAGCCAC-3′), Fbx3 (mouse) forward (5′-ACCCTCTGCTGCTCATCTTATCC-3′) and reverse (5′-CCACTAACTTTTGCCCGTTGTG-3′), HIPK2 forward (5′-GCTTCCAGCACAAGAACCACAC-3′) and reverse (5′-GCAATGACACAACCAAGGGACC-3′), p300 forward (5′-GCAATGGACAAAAAGGCAGTTC-3′) and reverse (5′-TGAGAGGAAGACACACAGGACAATC-3′), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase forward (5′-CTTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC-3′) and reverse (5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′), PML-RARα forward (5′-CCAATACAACGACAGCCCAGAAG-3′) and reverse (5′-CCATAGTGGTAGCCTGAGGACTTG-3′), and RARα forward (5′-CAGAACTGCTTGACCAAAGGACC-3′) and reverse (5′-AAGGCTTGTAGATGCGGGGTAGAG-3′). Real-time PCR was performed using the 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The expression of the p21 gene was normalized with respect to the expression of the TBP gene.

In vivo degradation assay.

BOSC23 cells were transfected with the desired vectors, increasing amounts of pcDNA-HA-Fbx3, and pFA-CMV for expression of the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4 BD) as an internal control. After 24 h, the cells were lysed. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

In vivo ubiquitination assay.

BOSC23 cells were transfected with the desired vectors. Cells were treated with 50 μM MG132 1 h before harvesting and lysed in lysis buffer. To assay the stabilization of ubiquitinated HIPK2, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.25% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholic acid, 5 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with Complete. The lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads as described above. Ubiquitinated HIPK2 was detected by immunoblotting with the antiubiquitin antibody, followed by treatment with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies as described above.

Immunofluorescence.

MCF7 cells were cultured in four-well chamber slides and transfected with pLNCX-FLAG-PML I and pcDNA-HA-Cul1, pcDNA-HA-Fbx3, or pcDNA-HA-Skp1, or pLNCX-FLAG-PML IV and pLNCX-HA-HIPK2 or pLNCX-HA-p300 by use of Lipofectamine 2000. The cells were treated with or without 10 μM MG132 for 18 h (HIPK2) or 9 h (p300). After MG132 treatment, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and incubated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer (1% FCS in PBS). Cells were incubated with the primary antibodies for 12 h at 4°C and then incubated with the secondary antibodies. The slides were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured on an Olympus microscope.

Luciferase assay.

H1299 cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation method or Lipofectamine 2000 in 24-well plates, and luciferase activity was assayed after 24 h with a Veritas luminometer (Turner Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). Results of reporter assays are represented as the mean values for relative luciferase activity generated from four independent experiments and normalized against the activity of the enzyme form phRG-TK as an internal control.

RESULTS

PML complex contains Cul1, Fbx3, and Skp1.

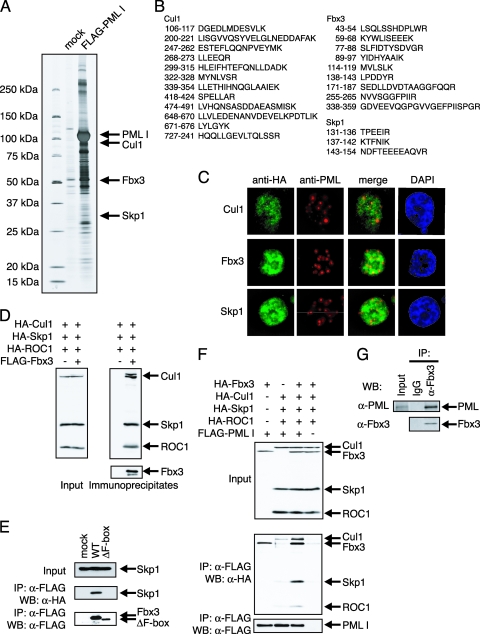

In order to clarify the role of PML in transcription, we purified the PML complex from the cell lysates of K562 cells expressing FLAG-tagged PML I and resolved the complex by SDS-PAGE. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis identified Cul1, Fbx3, and Skp1 as components of the PML complex (Fig. 1A and B). Other proteins identified in the PML complex are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. To test whether Cul1, Fbx3, or Skp1 interacts with PML I, we used immunofluorescence analysis. HA-tagged Cul1, HA-tagged Fbx3, or HA-tagged Skp1 was cotransfected with FLAG-tagged PML I into MCF7 cells, and the locations of these proteins were detected by anti-HA antibody (Cul1, Fbx3, or Skp1) or anti-PML antibody (PML I). PML I was localized in NBs, and Cul1, Fbx3, or Skp1 was colocalized with PML I at the peripheries of NBs (Fig. 1C). Colocalization of Fbx3 with PML I was detected more significantly than that of Cul1 and Skp1 (Fig. 1C). Cul1 and Skp1 are known to be components of SCF ubiquitin ligase (17). The function of Fbx3 was unknown, but it contains the F-box domain, which is found in a component of the SCF complex that determines substrate specificity (24). To confirm that Fbx3 was a component of the SCF complex, BOSC23 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged Fbx3 and HA-tagged Skp1, Cul1, and ROC1. In immunoblot analysis, HA-tagged Skp1, Cul1, and ROC1 coprecipitated with FLAG-tagged Fbx3 (Fig. 1D). The F-box domain is known to be a Skp1 interaction site (30). Therefore, we examined whether the F-box domain of Fbx3 was required for interaction with Skp1. The Fbx3 mutant lacking the F-box domain (ΔF-box mutant; deletion of the region from 61 to 471) did not coprecipitate with Skp1 (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that Fbx3 can form an SCF ubiquitin ligase (SCFFbx3).

FIG. 1.

Ubiquitin ligase SCFFbx3 is part of the PML complex. (A) Purification of the PML complex. The PML complex was purified from cell lysates prepared from K562 cells carrying an empty vector (mock) or stably expressing FLAG-tagged PML I. The complexes were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated agarose, and the bound materials were eluted with the FLAG peptide. The eluates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. The proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. (B) The amino acid sequences of the peptides derived from the fractions specific to the FLAG-PML I-expressing cells. The proteins in the specific fractions were identified as Cul1, Fbx3, and Skp1. (C) Cul1, Fbx3, and Skp1 colocalized with PML I. MCF7 cells were cotransfected with pLNCX-FLAG-PML I and pcDNA-HA-Cul1, pcDNA-HA-Fbx3, or pcDNA-HA-Skp1. Cul1, Fbx3, and Skp1 were stained with anti-HA antibody and PML I was stained with anti-PML (001) antibody. DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (D) Fbx3 forms a complex with Skp1, Cul1, and ROC1. BOSC23 cells were transfected with pcDNA-HA-Skp1, pcDNA-HA-Cul1, pcDNA-HA-ROC1, and either the empty vector (−) or pcDNA-FLAG-Fbx3. The expression of Skp1, Cul1, and ROC1 in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody (left). The Fbx3 complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies (right). (E) The F-box domain is required for the interaction between Fbx3 and Skp1. BOSC23 cells were transfected with pcDNA-HA-Skp1 and either mock or pcDNA-FLAG-Fbx3 constructs as indicated. The expression of Skp1 in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody (top). The lysates of transfectants were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA (middle) and anti-FLAG (bottom) antibodies. (F) PML interacts with SCFFbx3 through Fbx3. BOSC23 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA-HA-Fbx3, pcDNA-HA-Skp1, pcDNA-HA-Cul1, pcDNA-HA-ROC1, and either mock empty vector or pLNCX-FLAG-PML I. The interactions between PML I and components of SCFFbx3 were analyzed as described for panel D. (G) Endogenous Fbx3 interacts with endogenous PML. SKNO-1 cells were lysed and Fbx3 was immunoprecipitated with anti-Fbx3 antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Fbx3 and anti-PML (H238) antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitate; WB, Western blot; α-, anti-.

As shown in Fig. 1A, components of SCFFbx3 were present in the PML complex. A coimmunoprecipitation assay was performed to determine the component of SCFFbx3 that was primarily responsible for mediating its interaction with PML. When cotransfected together, all of the components of SCFFbx3, including Fbx3, Skp1, Cul1, and ROC1, were efficiently coprecipitated with PML (Fig. 1F). However, PML could not be coprecipitated with Skp1, Cul1, or ROC1 efficiently without cotransfection with Fbx3 (Fig. 1F). In addition, a strong interaction between PML and Fbx3 was detected without cotransfection of the other SCFFbx3 components. To assess whether endogenous PML interacted with endogenous Fbx3, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays. We found that endogenous PML was efficiently coprecipitated with endogenous Fbx3 (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that Fbx3 mediates the interaction between SCFFbx3 and PML.

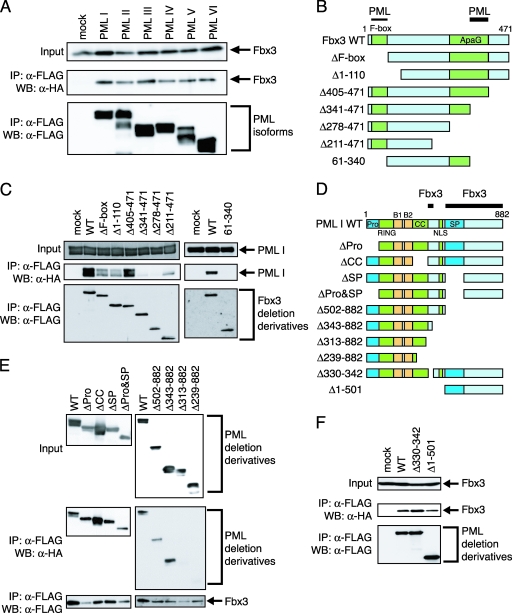

Since several isoforms of PML are known, we tested the interactions between PML isoforms and Fbx3. Coimmunoprecipitation analysis indicated that Fbx3 could be coprecipitated with all PML isoforms tested (I to VI) (Fig. 2A). To determine the domains in Fbx3 that are required for interaction with PML, HA-tagged PML I was cotransfected with FLAG-tagged Fbx3 deletion mutants, as shown schematically in Fig. 2B. Deletion of the regions from 341 to 404 and from 1 to 60 of Fbx3 are required for interaction with PML (Fig. 2C). The Fbx3 mutant (deletion of 61 to 340), which does not contain both regions, did not interact with PML I at all. To determine the domains in PML that are required for the interaction with Fbx3, FLAG-tagged Fbx3 was cotransfected with HA-tagged wild-type or truncated versions of PML, as shown schematically in Fig. 2D. Removal of the N-terminal proline-rich (Pro) region (1 to 55), the coiled-coil region (217 to 329), or the serine-proline region (502 to 553) did not affect the interaction with Fbx3. C-terminal deletions up to amino acid 343 did not affect the interaction, but further deletion up to 313 resulted in the loss of interaction (Fig. 2E). However, Fbx3 interacted with the PML mutant truncated between amino acids 330 and 342 (Fig. 2F). Fbx3 also interacted with the PML mutant with a truncation in its N-terminal region (Fig. 2F). Thus, the Fbx3 interaction sites of PML are located between amino acids 330 and 342, close to the coiled-coil region, and in the C-terminal region.

FIG. 2.

PML and Fbx3 interact with their respective specific domains. (A) PML isoforms interact with Fbx3. BOSC23 cells were transfected with pLNCX-HA-Fbx3 and either mock or pLNCX-FLAG-PML isoforms (I to VI). The expression of Fbx3 in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody (top). The lysates of transfectants were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA (middle) and anti-FLAG (bottom) antibodies. (B) Schematic diagram of the structures of Fbx3 deletion mutants. PML indicates the strongly interacting (thick line) and weakly interacting (thin line) regions of Fbx3 as determined for panel C. (C) Identification of Fbx3 regions required for interaction with PML. BOSC23 cells were transfected with pLNCX-HA-PML I and mock or pcDNA-FLAG-Fbx3 deletion constructs as indicated. The expression of PML I in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody (top). The lysates of transfectants were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA (middle) and anti-FLAG (bottom) antibodies. (D) Schematic diagram of the structures of PML deletion mutants. The proline-rich region (Pro), the RING finger domain (RING), B-box domain 1 (B1), B-box domain 2 (B2), the coiled-coil domain (CC), the nuclear import signal (NLS), and the serine-proline-rich region (SP) are indicated. Fbx3 indicates the interacting region of PML as determined for panels E and F. (E and F) Identification of PML regions required for interaction with Fbx3. BOSC23 cells were cotransfected with pLNCX-FLAG-Fbx3 and pLNCX-HA-PML deletion constructs (E) or with pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 and pLNCX-FLAG-PML deletion constructs (F) as indicated. The interactions between Fbx3 and the PML mutants were analyzed as described for panel C. IP, immunoprecipitate; WB, Western blot; WT, wild type; α-, anti-.

Fbx3 stimulates PML-mediated transcriptional activity of p53.

PML is known to activate p53-dependent transcription (15, 20). The fact that Fbx3 is a part of the PML complex (Fig. 1A) suggested that Fbx3 functions in PML-dependent transcriptional activation. To test the effect of Fbx3 on p53-dependent transcription, we performed reporter analyses using the MDM2 promoter. As shown in Fig. 3A, lane 8, PML IV activated p53-dependent transcription, as previously reported (15, 20). Although Fbx3 alone had little effect on p53-dependent transcription (Fig. 3A, lane 9), it activated p53-dependent transcription when cotransfected with PML IV (Fig. 3A, lane 11). In contrast, the ΔF-box mutant, which cannot form the SCF complex, did not activate transcription even in the presence of PML IV (Fig. 3A, lane 12). As shown in Fig. 2E, the region from amino acid 330 to 342 and the C-terminal region of PML are important for its interaction with Fbx3. We examined whether PML mutants lacking these regions (PML IV Δ330-342 and Δ502-882) would activate p53-dependent transcription. Unlike the PML IV wild type, PML IV Δ330-342 and Δ502-882 did not activate p53-mediated transcription (Fig. 3B). To determine whether Fbx3 is involved in PML-dependent transcriptional activation, we performed reporter analyses using siRNAs for Fbx3. Fbx3-specific siRNA (siFbx3) inhibited PML-dependent transcriptional activation, in contrast to the control siRNA (siControl) (Fig. 3C). The induction of p21, a p53 target gene, is known to be impaired in PML−/− cells (20). To examine whether Fbx3 contributes to the expression of p21, we used siRNA to knock down endogenous Fbx3 expression. Fbx3 depletion by siRNA impaired the adriamycin (ADR)-induced expression of p21 (Fig. 3D). Thus, SCFFbx3 stimulates PML-dependent transcriptional activation. These results suggest that the ubiquitination substrates of SCFFbx3 are factors that are involved in PML-dependent transcriptional activation.

FIG. 3.

PML and Fbx3 cooperatively activate p53-mediated transcription. (A) Fbx3 activates p53-mediated transcription cooperatively with PML. H1299 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of MDM2-luc, 50 ng of phRG-TK, and 5 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-p53, 100 ng of pLNCX-HA-PML IV, and/or 200 ng of pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 or pcDNA-HA-ΔF-box. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity at 24 h after transfection. Values represent means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from four independent determinations. (B) The Fbx3 interaction sites of PML are needed for the activation of p53-dependent transcription. H1299 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of MDM2-luc, 50 ng of phRG-TK, and 5 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-p53 and/or 100 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-PML IV, pLNCX-FLAG-PML IV Δ330-342, or pLNCX-HA-PML Δ502-882. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity at 24 h after transfection. Values represent means ± SEM from four independent determinations. (C) Fbx3 is involved in PML-dependent transcriptional activation. H1299 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of MDM2-luc, 50 ng of phRG-TK, 5 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-p53, and 50 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-PML IV and/or 100 pmol siControl or siFbx3 by using Lipofectamine 2000. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity at 24 h after transfection. Values represent means ± SEM from four independent determinations (top). The primers for RT-PCR (bottom) are described in Materials and Methods. (D) Expression of p21 is decreased by knocking down Fbx3. MOLT-4 cells were transfected with siControl or siFbx3 and then treated with 0.5 μM ADR. The primers for RT-PCR (top) are described in Materials and Methods. The expression of p21 was analyzed by real-time PCR (bottom). Values represent means ± SEM from four independent determinations. *, P value of <0.001 compared with the siControl value for the 6-h time point. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

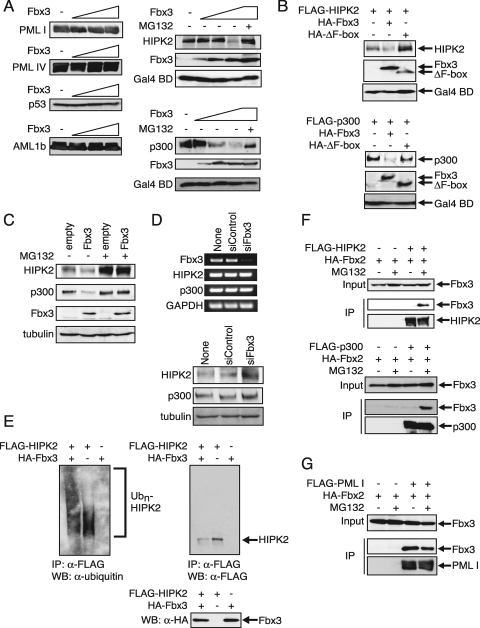

HIPK2 and p300 are the targets of SCFFbx3.

It has been reported that PML, HIPK2, and p300 activate p53-dependent transcription (3, 13, 22, 38, 42) as well as AML1-dependent transcription (1, 32, 44). p53, AML1, HIPK2, and p300 are known to interact with PML and therefore could be potential targets of SCFFbx3. To test whether Fbx3 promoted the degradation of these proteins, increasing amounts of Fbx3 were cotransfected with PML I, PML IV, p53, AML1, HIPK2, and p300. Although Fbx3 had no effect on the levels of PML I, PML IV, p53, or AML1 (Fig. 4A), it decreased the levels of HIPK2 and p300 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). These decreases were inhibited by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 4A). The ΔF-box mutant did not decrease the levels of either HIPK2 or p300 (Fig. 4B). To examine whether endogenous HIPK2 and p300 were degraded by Fbx3, NIH 3T3 cells were infected with an empty retrovirus or a retrovirus encoding Fbx3 and cultured in the absence or presence of MG132. Immunoblot analysis indicated that Fbx3 overexpression decreased the levels of endogenous HIPK2 and p300 in the absence of MG132 but not in the presence of MG132 (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that SCFFbx3 induces a proteasome-dependent degradation of HIPK2 and p300.

FIG. 4.

HIPK2 and p300 are the targets of SCFFbx3. (A) Fbx3 induces the degradation of HIPK2 and p300. BOSC23 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-PML I, pLNCX-FLAG-PML IV, pLNCX-FLAG-p53, pLNCX-FLAG-AML1b, pLNCX-FLAG-HIPK2, or pLNCX-FLAG-p300; 100 ng of pFA-CMV for the expression of Gal4 BD as an internal control; and increasing amounts of pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 (0, 50, 200, and 800 ng). The expression of PML I, PML IV, p53, AML1, HIPK2, or p300 in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody. The expression of Fbx3 and Gal4 BD in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA and anti-Gal4 antibodies, respectively. MG132 was added as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The F-box domain of Fbx3 is essential for the degradation of HIPK2 and p300. BOSC23 cells were cotransfected with pLNCX-FLAG-HIPK2 or pLNCX-FLAG-p300, pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 or pcDNA-HA-ΔF-box, and pFA-CMV. The cell lysates were analyzed as described for panel A. (C) Overexpression of Fbx3 induces the degradation of endogenous HIPK2 and p300. NIH 3T3 infectants with an empty retrovirus (empty) or a retrovirus encoding Fbx3, cultured in the absence or presence of MG132, were lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The expression of HIPK2, p300, Fbx3, and tubulin was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HIPK2, anti-p300, anti-HA, and antitubulin antibodies, respectively. (D) Expression of HIPK2 and p300 is increased by knocking down Fbx3. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with siControl or siFbx3 five times. The primers for the RT-PCR (top) are described in Materials and Methods. The expression of HIPK2, p300, and tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting (bottom) using anti-HIPK2, anti-p300, and antitubulin, respectively. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (E) Fbx3 ubiquitinates HIPK2. BOSC23 cells were transfected with the desired vectors. Cells were treated with 50 μM MG132 and lysed. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody as described in Materials and Methods. The ubiquitination of HIPK2 was analyzed by immunoblotting using antiubiquitin. (F) HIPK2 and p300 interact with Fbx3 in the presence of MG132. BOSC23 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 and mock empty vector, pLNCX-FLAG-HIPK2 (top), or pLNCX-FLAG-p300 (bottom). Cells were treated with or without 10 μM MG132 for 9 h. The expression of Fbx3 in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody (Input). The lysates of transfectants were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibodies (middle) and anti-FLAG antibodies (bottom). (G) PML interacts with Fbx3. BOSC23 cells were transfected with pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 and either mock empty vector or pLNCX-FLAG-PML I. The interaction between Fbx3 and PML I was analyzed as described for panel F. IP, immunoprecipitate; WB, Western blot; α-, anti-.

To determine whether endogenous HIPK2 and p300 were degraded by endogenous SCFFbx3, we used siRNA to knock down endogenous Fbx3 expression. Transfection of NIH 3T3 cells with Fbx3 siRNA resulted in a decrease in Fbx3 mRNA levels (Fig. 4D, top). Fbx3 depletion by siRNA did not affect HIPK2 and p300 mRNA levels (Fig. 4D, top) but rather increased HIPK2 and p300 protein levels (Fig. 4D, bottom). These data demonstrate that the stability of HIPK2 and p300 is regulated by SCFFbx3.

In order to clarify whether SCFFbx3 degrades HIPK2 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, we examined whether Fbx3 induced the ubiquitination of HIPK2. BOSC23 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged HIPK2 and HA-tagged Fbx3 and then treated with MG132. HIPK2 proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitates by use of antiubiquitin antibody indicated that Fbx3 stimulated the ubiquitination of HIPK2 (Fig. 4E). However, the ΔF-box mutant did not stimulate the ubiquitination of HIPK2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that SCFFbx3 induces the ubiquitination of HIPK2. Unfortunately, we could not detect the ubiquitination of p300. This may have been because the large size of polyubiquitinated p300 prevented its efficient transfer to filters during immunoblotting.

In general, an F-box protein in the SCF complex interacts with the target proteins (30). To confirm that HIPK2 and p300 are the targets of SCFFbx3, we examined whether Fbx3 interacts with HIPK2 and p300. BOSC23 cells were transfected with HA-tagged Fbx3 and FLAG-tagged HIPK2 or p300. Fbx3 coprecipitated with HIPK2 or p300 only when MG132 was added (Fig. 4F), most likely because HIPK2 and p300 interaction with Fbx3 resulted in their immediate degradation by the proteasome. HIPK2 interacted with the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of Fbx3 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, PML, which is not a substrate for SCFFbx3, interacted equally with Fbx3 in the presence or absence of MG132 (Fig. 4G).

PML inhibits Fbx3-induced degradation of HIPK2 and p300.

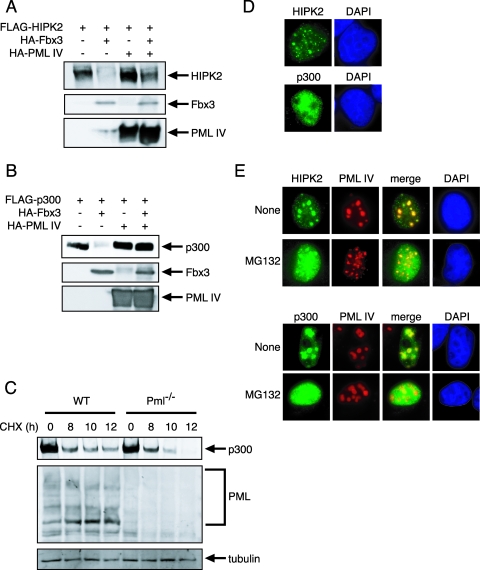

The fact that SCFFbx3 is a part of the PML complex (Fig. 1A) suggested that PML plays a role in the Fbx3-mediated degradation of HIPK2 and p300 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. To test this possibility, BOSC23 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged HIPK2 or p300, HA-tagged Fbx3, and HA-tagged PML IV. Western blot analysis showed that PML IV inhibited the Fbx3-mediated degradation of HIPK2 and p300 (Fig. 5A and B). We examined whether PML mutants lacking the Fbx3-interacting regions (PML IV Δ330-342 and Δ502-882) would inhibit the Fbx3-mediated degradation of HIPK2. PML IV Δ330-342 did not inhibit the Fbx3-mediated degradation of HIPK2 (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). However, PML IV Δ502-882 inhibited the Fbx3-mediated degradation of HIPK2 (data not shown). These results indicate that the region of amino acids 330 to 342 of PML is important for the stabilization of HIPK2. To examine the effect of PML on the stability of endogenous p300, BM cells from wild-type and Pml−/− mice were treated with cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein synthesis. After CHX treatment, endogenous p300 was degraded faster in Pml−/− cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 5C; also see Fig. S3B in the supplemental material). Endogenous HIPK2 was not detected in wild-type or Pml−/− BM cells or in murine embryonic fibroblasts (data not shown). These data suggest that PML stabilizes p300 by inhibiting its SCFFbx3-mediated degradation.

FIG. 5.

PML inhibits SCFFbx3-induced degradation of HIPK2 and p300. (A) PML inhibits the degradation of HIPK2 by Fbx3. pLNCX-FLAG-HIPK2 (200 ng) and pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 (800 ng) and/or pLNCX-HA-PML IV (250 ng) were cotransfected into BOSC23 cells. The expression of HIPK2 in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody (top). The expression of Fbx3 (middle) and PML IV (bottom) in the lysates of transfectants was detected by immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. (B) PML inhibits the degradation of p300 by Fbx3. pLNCX-FLAG-p300 (200 ng) and pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 (800 ng) and/or pLNCX-HA-PML IV (200 ng) were cotransfected into BOSC23 cells. The expression of p300 (top), Fbx3 (middle), and PML IV (bottom) was detected as described for panel A. (C) PML stabilizes p300. Wild-type (WT) and Pml−/− BM cells were treated with 100 μg/ml CHX. The expression of p300, PML, and tubulin was detected by immunoblotting using anti-p300, anti-PML (36.1-104), and antitubulin antibodies, respectively. (D) Localization of HIPK2 and p300 in the nucleus. MCF7 cells were transfected with pLNCX-HA-HIPK2 or pLNCX-HA-p300. The localization of HIPK2 and p300 was analyzed by use of anti-HA antibody. (E) HIPK2 and p300 are localized outside of NBs in the presence of MG132. MCF7 cells were cotransfected with pLNCX-FLAG-PML IV and pLNCX-HA-HIPK2 or pLNCX-HA-p300. Cells were treated with or without 10 μM MG132. HIPK2 and p300 were stained with anti-HA antibody and PML IV was stained with anti-PML (001) antibody. DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

PML is known to accumulate in NBs together with many other proteins, such as HIPK2 and p300. We hypothesized that PML might stabilize HIPK and p300 by sequestering them in NBs away from ubiquitin-proteasome-related proteins in the nucleus. We used immunofluorescence analysis to test this hypothesis. HA-tagged HIPK2 or HA-tagged p300 was cotransfected with FLAG-tagged PML IV into MCF7 cells, and the locations of these proteins were detected by anti-HA antibody and anti-PML antibody, respectively. Without cotransfection with PML, HIPK2 was localized in microspeckles and p300 showed a diffuse staining pattern in the nucleus (Fig. 5D). When coexpressed with PML IV, HIPK2 and p300 colocalized with PML IV in NBs (Fig. 5E). When HIPK2 and p300 were cotransfected with PML IV, followed by treatment with MG132, HIPK2 and p300 were localized to both the inside and outside of NBs. In contrast, PML was localized only in NBs before and after treatment with MG132 (Fig. 5E). Thus, MG132 stabilized HIPK2 and p300 outside of the NBs but not in the NBs. These results suggest that HIPK2 and p300 are degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway when located outside of NBs and stabilized by PML when located within NBs.

PML does not inhibit the ubiquitination of HIPK2 by SCFFbx3.

PML inhibited the degradation of HIPK2 by SCFFbx3 (Fig. 5A). To test whether PML affects the Fbx3-induced ubiquitination of HIPK2, BOSC23 cells were cotransfected with FLAG-tagged HIPK2, HA-tagged Fbx3, and HA-tagged PML IV. Without proteasome inhibitors, Fbx3 induced the degradation of HIPK2 (Fig. 6A, lane 3), and PML inhibited this degradation of HIPK2 (Fig. 6A, lane 4). However, the levels of ubiquitinated HIPK2 were increased when HIPK2 was cotransfected together with both PML and Fbx3 (Fig. 6A, lane 4). These results suggest that PML inhibits the degradation of HIPK2 through a mechanism that does not involve the inhibition of its ubiquitination by SCFFbx3.

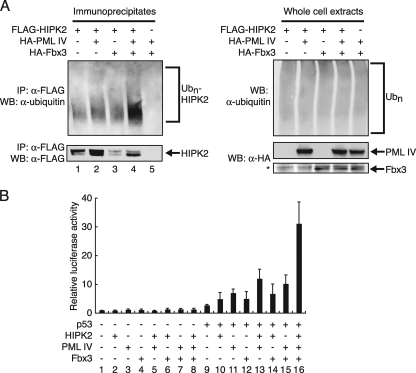

FIG. 6.

PML stabilization of ubiquitinated HIPK2 is related to the transcriptional activity of p53. (A) PML stabilizes ubiquitinated HIPK2. BOSC23 cells were transfected with pLNCX-FLAG-HIPK2 and/or pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 and/or pLNCX-HA-PML IV. Cells were lysed as described in Materials and Methods. The immunoprecipitates by anti-FLAG antibody were analyzed by immunoblotting using antiubiquitin antibody. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band present in all samples. (B) HIPK2, PML, and Fbx3 activate p53-dependent transcription synergistically. H1299 cells were cotransfected with 200 ng of MDM2-luc, 50 ng of phRG-TK, and 2.5 ng of pLNCX-FLAG-p53 or 700 ng of pLNCX-HA-HIPK2, 100 ng of pLNCX-HA-PML IV, and/or 200 ng of pcDNA-HA-Fbx3 as indicated. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity at 24 h after transfection. Values represent means ± SEM from four independent determinations. IP, immunoprecipitate; WB, Western blot; α-, anti-.

It has been reported that HIPK2 activates p53-dependent transcription (13, 22). To clarify the roles of HIPK2, PML IV, and Fbx3 in p53-dependent transcription, we performed reporter analyses using the MDM2 promoter with H1299 cells. HIPK2 increased p53 transcriptional activity (Fig. 6B, lane 10) as previously reported. Furthermore, HIPK2 and PML IV activated p53-mediated transcription cooperatively (Fig. 6B, lane 13). Since Fbx3 promotes the degradation of HIPK2, we initially thought that Fbx3 might inhibit the activation of p53-dependent transcription by HIPK2 and PML IV. However, Fbx3 stimulated this transcriptional activation (Fig. 6B, lane 16). These results are consistent with the results in Fig. 3A, which show that Fbx3 increases PML IV-mediated p53 transcriptional activity. Thus, HIPK2, PML IV, and Fbx3 activate p53-dependent transcription synergistically.

PML-RARα destabilizes HIPK2.

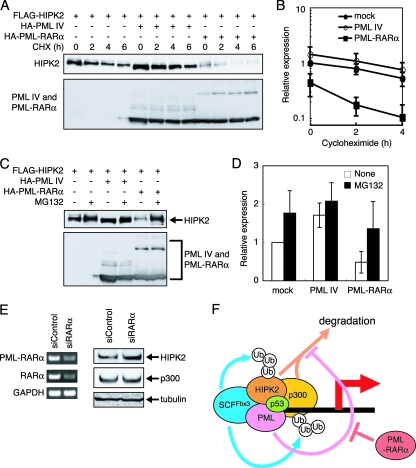

PML-RARα is known to be a dominant-negative form of PML (49, 57). Therefore, we hypothesized that PML-RARα would not stabilize HIPK2. To test whether PML-RARα affects the stability of HIPK2, FLAG-tagged HIPK2 was mock transfected or cotransfected with PML IV or PML-RARα. As shown in Fig. 7A, the levels of HIPK2 did not decrease when it was cotransfected with PML IV. In contrast, the levels of HIPK2 decreased when it was transfected with PML-RARα. The stability of HIPK2 was also decreased by PML-RARα (Fig. 7B). This decrease in HIPK2 levels was rescued by adding MG132 (Fig. 7C and D). These data indicate that PML-RARα promotes the degradation of HIPK2 in a ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent manner. HIPK2 levels also decreased when it was cotransfected with the PML-RARα mutant truncated between amino acids 330 and 342 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). To examine whether PML-RARα destabilizes endogenous HIPK2, we used siRNA for RARα to knock down PML-RARα expression in APL-derived NB4 cells. PML-RARα depletion increased the expression of endogenous HIPK2 (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that PML-RARα enhances HIPK2 degradation not by directly binding to Fbx3 but by inhibiting PML's stabilization of HIPK2.

FIG. 7.

PML-RARα destabilizes HIPK2. (A) PML-RARα enhances the degradation of HIPK2. BOSC23 cells were transfected with the appropriate vectors. Cells were treated with 100 μg/ml CHX and lysed. The expression of HIPK2 (top) and PML IV or PML-RARα (bottom) was detected by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. (B) Quantitative analysis of HIPK2 levels following CHX treatment. Values were normalized to the mock value at the zero time point. Values represent means ± SEM from four independent determinations. (C) PML-RARα promotes the degradation of HIPK2 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. BOSC23 cells were transfected with the appropriate vectors. Cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 and lysed. The lysates were analyzed as described for panel A. (D) Quantitative analysis of HIPK2 levels following MG132 treatment. Values were normalized to the nontreated mock value. Values represent means ± SEM from four independent determinations. (E) PML-RARα depletion increases the expression of HIPK2. NB4 cells were transfected with siControl or RARα-specific siRNA (siRARα). The primers for RT-PCR (left) are described in Materials and Methods. The expression of HIPK2, p300, and tubulin was analyzed by Western blot analysis (right) using anti-HIPK2, anti-p300, and antitubulin antibodies, respectively. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (F) A model for PML-mediated transcriptional activation. HIPK2 and p300 are the targets of SCFFbx3. Without PML, SCFFbx3 degrades HIPK2 and p300 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. PML stabilizes HIPK2 and p300 and inhibits their SCFFbx3-induced degradation. This stabilization of transcription coactivators by PML may activate transcription. PML-RARα acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor and destabilizes transcription coactivators. Ub, ubiquitin.

DISCUSSION

HIPK2 and p300 are novel targets of SCFFbx3.

In this study, we identified Fbx3 as a PML-interacting protein and as a subunit of SCF ubiquitin ligase that promoted the degradation of HIPK2 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Recently, Rinaldo and coworkers showed that MDM2 induced the degradation of HIPK2 in response to cytostatic doses of ADR or UV irradiation and that the C-terminal region of HIPK2 is critical for this degradation (50). Gresko and coworkers showed that the sumoylation of human HIPK2 at lysine 25 increased its stability (19). However, in this study, we found that Fbx3 could degrade mutants of HIPK2 deleted for the C-terminal region containing the lysine residue required for MDM2-mediated degradation, as well as the kinase-dead mutant (mutation of lysine 221 to alanine) and the HIPK2 K25R mutant, which cannot be sumoylated (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material), and that Fbx3 depletion by siRNA did not inhibit the repression of HIPK2 by ADR (see Fig. S5C in the supplemental material). These data suggest that the N-terminal region of HIPK2, but not the C-terminal region, is necessary for SCFFbx3-induced degradation. Although we were unable to identify which lysine residue(s) is necessary for ubiquitination and degradation by SCFFbx3, it appears that HIPK2 degradation by SCFFbx3 is different from MDM2-induced degradation and does not require lysine 25.

The degradation of p300 via the 26S proteasome pathway has previously been reported (6, 36, 48). This degradation appears to be dependent on p300 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (9, 47). Doxorubicin-activated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates p300 and induces p300 degradation (47). Protein phosphatase 2A, a serine-threonine phosphatase, also plays an important role in p300 degradation (9). Our data show that p300 is degraded by SCFFbx3 via the 26S proteasome pathway, although it is unclear which modification of p300 mediates this degradation. Nonetheless, Fbx3 interacted with a form of p300 that had a faster electrophoretic mobility on SDS-polyacrylamide gels in the presence of MG132 (data not shown), suggesting that SCFFbx3 recognizes and degrades dephosphorylated p300.

PML stimulates transcription by stabilizing HIPK2 and p300.

PML has been suggested to play a role in the transcription of target genes that are regulated by transcription factors such as p53. However, the underlying mechanism has remained unclear. Our results suggest that PML stimulates transcription by protecting transcription coactivators such as HIPK2 and p300 from proteasome-dependent degradation. We demonstrated that PML inhibits the degradation of HIPK2 and p300 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Fig. 5A and B) and that this inhibition occurs in NBs (Fig. 5E). PML has been suggested to increase protein stability. For instance, PML enhances p53 stability by sequestering MDM2 in the nucleolus (4) and inhibits p73 ubiquitin-dependent degradation (5, 45). These reports are in agreement with our data showing that PML increases protein stability. In particular, the colocalization of PML in NBs is required for the stabilization of HIPK2, p300, and p73. In contrast, other groups have shown that NBs act as sites for proteasomal protein degradation by recruiting subunits of proteasomes and ubiquitin (2, 34, 35). However, these studies showed only that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway-related proteins were recruited to NBs. There has been no report showing that proteasomal protein degradation actually occurs in NBs. Therefore, we suggest that PML may regulate protein stability by inhibiting protein degradation within NBs, while still allowing protein degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to occur around the outside of NBs. In fact, the components of SCFFbx3 which are essential for the degradation of HIPK2 and p300 were localized at the peripheries of NBs (Fig. 1C). In this way, it would be possible to finely regulate protein stability/degradation at the peripheries of NBs. Thus, it is not surprising in this respect that the proteins linked to degradation, proteasome subunits, and ubiquitin are found in NBs. As for the site of proteasomal protein degradation, Mattsson and coworkers showed that NB-associated proteins move to the nucleolus in the presence of MG132 and that the nucleolus may regulate proteasomal protein degradation (40). In the present study, we detected HIPK2 and p300 outside of NBs in the presence of MG132 but failed to detect PML, HIPK2, or p300 in the nucleolus (Fig. 5E). Although further studies concerning the actual site of proteasomal protein degradation will be required, it is clear from the work presented here and elsewhere that PML is crucial for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

As shown in Fig. 3A, Fbx3 and PML cooperatively activated p53-dependent transcription, and Fbx3 was required for the enhanced transcription activity of p53 mediated by PML (Fig. 3B and C). Furthermore, Fbx3 and PML synergistically enhanced the HIPK2-stimulated transcriptional activity of p53 (Fig. 6B). Since PML stabilized HIPK2 ubiquitinated by Fbx3 (Fig. 6A), these results suggest that the ubiquitination of HIPK2 stimulates the transcriptional activity of p53. Important roles for ubiquitin in transcriptional regulation have been reported (10). The F-box protein Skp2 induces the ubiquitination and degradation of c-Myc but upregulates c-Myc transcriptional activity (29, 55). Likewise, the E3 ubiquitin ligases RSP5 and E6-AP activate hormone receptor-dependent transcription (25, 43), and SCFMet30-induced ubiquitination of VP16 appears to be essential for transcriptional activation (51). Taken together, these findings indicate that stabilizing ubiquitinated HIPK2 appears to upregulate the transcriptional activity of p53 as shown in Fig. 6B. We speculate that ubiquitinated HIPK2 could activate p53-dependent transcription by increasing the phosphorylation of p300 and p53. It is also possible that ubiquitinated HIPK2 and p300 are degraded rapidly after the completion of the transcription of their target genes to ensure the complete shutdown of transcription. The regulation of the exact timing and levels of transcription in this way could constitute a novel mechanism for regulating gene expression.

Dysfunction of HIPK2 and p300 in leukemia pathogenesis.

It has been reported that the PML-RARα fusion, which is generated by the chromosome translocation t(15;17) found for APL, forms stable oligomers with normal PML and inhibits PML-mediated transcriptional activation in a dominant-negative manner. We have shown here that PML and PML-RARα play opposite roles in HIPK2 stability (Fig. 7A to D). This may be because PML-RARα disrupts NBs, in which HIPK2 is stabilized as shown in Fig. 5A and E. The result showing that removal of the Fbx3-interacting region of PML-RARα destabilized HIPK2 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) also suggests that the disruption of NBs by PML-RARα decreases protein stability. As PML-RARα enhanced HIPK2 degradation, PML-RARα would repress transcription by destabilizing coactivators such as HIPK2 and p300, perhaps contributing in this way to the pathogenesis of leukemia. Mutations in HIPK2 and p300 have been found for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome. p300 is involved in chromosome translocations such as t(8;22) and t(11;22) found in AML (8, 23, 31). We have recently found mutations in the HIPK2 gene in association with AML and myelodysplastic syndrome that impair p53- and AML1-mediated transcription (37). These results suggest that dysfunctions of HIPK2 and p300 may be implicated in leukemia.

In summary, we propose that transcription is regulated by SCFFbx3 and PML, as shown in Fig. 7F. According to this model, PML would activate transcription by counteracting the degradation of the transcription coactivators HIPK2 and p300, whose degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is mediated by the novel SCFFbx3 ubiquitin ligase. Conversely, PML-RARα would inactivate transcription by blocking the function of PML, thereby enhancing the SCFFbx3-induced degradation of HIPK2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Taya (National Cancer Center Research Institute) for kindly providing the cDNAs for p53 cDNA and the MDM2-luc reporter. We also thank Yukiko Aikawa, Noriko Aikawa, and Chikako Hatanaka for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and by the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies from the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 September 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aikawa, Y., L. A. Nguyen, K. Isono, N. Takakura, Y. Tagata, M. L. Schmitz, H. Koseki, and I. Kitabayashi. 2006. Roles of HIPK1 and HIPK2 in AML1- and p300-dependent transcription, hematopoiesis and blood vessel formation. EMBO J. 253955-3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anton, L. C., U. Schubert, I. Bacik, M. F. Princiotta, P. A. Wearsch, J. Gibbs, P. M. Day, C. Realini, M. C. Rechsteiner, J. R. Bennink, and J. W. Yewdell. 1999. Intracellular localization of proteasomal degradation of a viral antigen. J. Cell Biol. 146113-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avantaggiati, M. L., V. Ogryzko, K. Gardner, A. Giordano, A. S. Levine, and K. Kelly. 1997. Recruitment of p300/CBP in p53-dependent signal pathways. Cell 891175-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernardi, R., P. P. Scaglioni, S. Bergmann, H. F. Horn, K. H. Vousden, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2004. PML regulates p53 stability by sequestering Mdm2 to the nucleolus. Nat. Cell Biol. 6665-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernassola, F., P. Salomoni, A. Oberst, C. J. Di Como, M. Pagano, G. Melino, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2004. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p73 is inhibited by PML. J. Exp. Med. 1991545-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouillard, F., and C. E. Cremisi. 2003. Concomitant increase of histone acetyltransferase activity and degradation of p300 during retinoic acid-induced differentiation of F9 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27839509-39516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cenciarelli, C., D. S. Chiaur, D. Guardavaccaro, W. Parks, M. Vidal, and M. Pagano. 1999. Identification of a family of human F-box proteins. Curr. Biol. 91177-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaffanet, M., L. Gressin, C. Preudhomme, V. Soenen-Cornu, D. Birnbaum, and M. J. Pebusque. 2000. MOZ is fused to p300 in an acute monocytic leukemia with t(8;22). Genes Chromosomes Cancer 28138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., J. R. St-Germain, and Q. Li. 2005. B56 regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A mediates valproic acid-induced p300 degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25525-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conaway, R. C., C. S. Brower, and J. W. Conaway. 2002. Emerging roles of ubiquitin in transcription regulation. Science 2961254-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de The, H., C. Chomienne, M. Lanotte, L. Degos, and A. Dejean. 1990. The t(15;17) translocation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia fuses the retinoic acid receptor alpha gene to a novel transcribed locus. Nature 347558-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de The, H., C. Lavau, A. Marchio, C. Chomienne, L. Degos, and A. Dejean. 1991. The PML-RAR alpha fusion mRNA generated by the t(15;17) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia encodes a functionally altered RAR. Cell 66675-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Orazi, G., B. Cecchinelli, T. Bruno, I. Manni, Y. Higashimoto, S. Saito, M. Gostissa, S. Coen, A. Marchetti, G. Del Sal, G. Piaggio, M. Fanciulli, E. Appella, and S. Soddu. 2002. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 phosphorylates p53 at Ser 46 and mediates apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 411-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyck, J. A., G. G. Maul, W. H. Miller, Jr., J. D. Chen, A. Kakizuka, and R. M. Evans. 1994. A novel macromolecular structure is a target of the promyelocyte-retinoic acid receptor oncoprotein. Cell 76333-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fogal, V., M. Gostissa, P. Sandy, P. Zacchi, T. Sternsdorf, K. Jensen, P. P. Pandolfi, H. Will, C. Schneider, and G. Del Sal. 2000. Regulation of p53 activity in nuclear bodies by a specific PML isoform. EMBO J. 196185-6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilliland, D. G. 1998. Molecular genetics of human leukemia. Leukemia 12(Suppl. 1)S7-S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glickman, M. H., and A. Ciechanover. 2002. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 82373-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goddard, A. D., J. Borrow, P. S. Freemont, and E. Solomon. 1991. Characterization of a zinc finger gene disrupted by the t(15;17) in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Science 2541371-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gresko, E., A. Moller, A. Roscic, and M. L. Schmitz. 2005. Covalent modification of human homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 by SUMO-1 at lysine 25 affects its stability. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 3291293-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo, A., P. Salomoni, J. Luo, A. Shih, S. Zhong, W. Gu, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2000. The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2730-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haupt, Y., R. Maya, A. Kazaz, and M. Oren. 1997. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature 387296-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann, T. G., A. Moller, H. Sirma, H. Zentgraf, Y. Taya, W. Droge, H. Will, and M. L. Schmitz. 2002. Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2. Nat. Cell Biol. 41-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ida, K., I. Kitabayashi, T. Taki, M. Taniwaki, K. Noro, M. Yamamoto, M. Ohki, and Y. Hayashi. 1997. Adenoviral E1A-associated protein p300 is involved in acute myeloid leukemia with t(11;22)(q23;q13). Blood 904699-4704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilyin, G. P., M. Rialland, C. Pigeon, and C. Guguen-Guillouzo. 2000. cDNA cloning and expression analysis of new members of the mammalian F-box protein family. Genomics 6740-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imhof, M. O., and D. P. McDonnell. 1996. Yeast RSP5 and its human homolog hRPF1 potentiate hormone-dependent activation of transcription by human progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 162594-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isono, K., K. Nemoto, Y. Li, Y. Takada, R. Suzuki, M. Katsuki, A. Nakagawara, and H. Koseki. 2006. Overlapping roles for homeodomain-interacting protein kinases Hipk1 and Hipk2 in the mediation of cell growth in response to morphogenetic and genotoxic signals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 262758-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen, K., C. Shiels, and P. S. Freemont. 2001. PML protein isoforms and the RBCC/TRIM motif. Oncogene 207223-7233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakizuka, A., W. H. Miller, Jr., K. Umesono, R. P. Warrell, Jr., S. R. Frankel, V. V. Murty, E. Dmitrovsky, and R. M. Evans. 1991. Chromosomal translocation t(15;17) in human acute promyelocytic leukemia fuses RAR alpha with a novel putative transcription factor, PML. Cell 66663-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, S. Y., A. Herbst, K. A. Tworkowski, S. E. Salghetti, and W. P. Tansey. 2003. Skp2 regulates Myc protein stability and activity. Mol. Cell 111177-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kipreos, E. T., and M. Pagano. 2000. The F-box protein family. Genome Biol. 1REVIEWS3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitabayashi, I., Y. Aikawa, A. Yokoyama, F. Hosoda, M. Nagai, N. Kakazu, T. Abe, and M. Ohki. 2001. Fusion of MOZ and p300 histone acetyltransferases in acute monocytic leukemia with a t(8;22)(p11;q13) chromosome translocation. Leukemia 1589-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitabayashi, I., A. Yokoyama, K. Shimizu, and M. Ohki. 1998. Interaction and functional cooperation of the leukemia-associated factors AML1 and p300 in myeloid cell differentiation. EMBO J. 172994-3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubbutat, M. H., S. N. Jones, and K. H. Vousden. 1997. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature 387299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lafarga, M., M. T. Berciano, E. Pena, I. Mayo, J. G. Castano, D. Bohmann, J. P. Rodrigues, J. P. Tavanez, and M. Carmo-Fonseca. 2002. Clastosome: a subtype of nuclear body enriched in 19S and 20S proteasomes, ubiquitin, and protein substrates of proteasome. Mol. Biol. Cell 132771-2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lallemand-Breitenbach, V., J. Zhu, F. Puvion, M. Koken, N. Honore, A. Doubeikovsky, E. Duprez, P. P. Pandolfi, E. Puvion, P. Freemont, and H. de The. 2001. Role of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) sumolation in nuclear body formation, 11S proteasome recruitment, and As2O3-induced PML or PML/retinoic acid receptor alpha degradation. J. Exp. Med. 1931361-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, Q., A. Su, J. Chen, Y. A. Lefebvre, and R. J. Hache. 2002. Attenuation of glucocorticoid signaling through targeted degradation of p300 via the 26S proteasome pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 162819-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, X. L., Y. Arai, H. Harada, Y. Shima, H. Yoshida, S. Rokudai, Y. Aikawa, A. Kimura, and I. Kitabayashi. 2007. Mutations of the HIPK2 gene in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome impair AML1- and p53-mediated transcription. Oncogene 267231-7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lill, N. L., S. R. Grossman, D. Ginsberg, J. DeCaprio, and D. M. Livingston. 1997. Binding and modulation of p53 by p300/CBP coactivators. Nature 387823-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Look, A. T. 1997. Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science 2781059-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattsson, K., K. Pokrovskaja, C. Kiss, G. Klein, and L. Szekely. 2001. Proteins associated with the promyelocytic leukemia gene product (PML)-containing nuclear body move to the nucleolus upon inhibition of proteasome-dependent protein degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 981012-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyoshi, H., K. Shimizu, T. Kozu, N. Maseki, Y. Kaneko, and M. Ohki. 1991. t(8;21) breakpoints on chromosome 21 in acute myeloid leukemia are clustered within a limited region of a single gene, AML1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8810431-10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moller, A., H. Sirma, T. G. Hofmann, S. Rueffer, E. Klimczak, W. Droge, H. Will, and M. L. Schmitz. 2003. PML is required for homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2)-mediated p53 phosphorylation and cell cycle arrest but is dispensable for the formation of HIPK domains. Cancer Res. 634310-4314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nawaz, Z., D. M. Lonard, C. L. Smith, E. Lev-Lehman, S. Y. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, and B. W. O'Malley. 1999. The Angelman syndrome-associated protein, E6-AP, is a coactivator for the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. Mol. Cell. Biol. 191182-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen, L. A., P. P. Pandolfi, Y. Aikawa, Y. Tagata, M. Ohki, and I. Kitabayashi. 2005. Physical and functional link of the leukemia-associated factors AML1 and PML. Blood 105292-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oberst, A., M. Rossi, P. Salomoni, P. P. Pandolfi, M. Oren, G. Melino, and F. Bernassola. 2005. Regulation of the p73 protein stability and degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331707-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson, M., R. Carbone, C. Sebastiani, M. Cioce, M. Fagioli, S. Saito, Y. Higashimoto, E. Appella, S. Minucci, P. P. Pandolfi, and P. G. Pelicci. 2000. PML regulates p53 acetylation and premature senescence induced by oncogenic Ras. Nature 406207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poizat, C., P. L. Puri, Y. Bai, and L. Kedes. 2005. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of p300 by doxorubicin-activated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in cardiac cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 252673-2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poizat, C., V. Sartorelli, G. Chung, R. A. Kloner, and L. Kedes. 2000. Proteasome-mediated degradation of the coactivator p300 impairs cardiac transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 208643-8654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rabbitts, T. H. 1994. Chromosomal translocations in human cancer. Nature 372143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rinaldo, C., A. Prodosmo, F. Mancini, S. Iacovelli, A. Sacchi, F. Moretti, and S. Soddu. 2007. MDM2-regulated degradation of HIPK2 prevents p53Ser46 phosphorylation and DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell 25739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salghetti, S. E., A. A. Caudy, J. G. Chenoweth, and W. P. Tansey. 2001. Regulation of transcriptional activation domain function by ubiquitin. Science 2931651-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salomoni, P., and P. P. Pandolfi. 2002. The role of PML in tumor suppression. Cell 108165-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi, Y., V. Lallemand-Breitenbach, J. Zhu, and H. de The. 2004. PML nuclear bodies and apoptosis. Oncogene 232819-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka, K., T. Suzuki, N. Hattori, and Y. Mizuno. 2004. Ubiquitin, proteasome and parkin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.von der Lehr, N., S. Johansson, S. Wu, F. Bahram, A. Castell, C. Cetinkaya, P. Hydbring, I. Weidung, K. Nakayama, K. I. Nakayama, O. Soderberg, T. K. Kerppola, and L. G. Larsson. 2003. The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol. Cell 111189-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, Z. G., D. Ruggero, S. Ronchetti, S. Zhong, M. Gaboli, R. Rivi, and P. P. Pandolfi. 1998. PML is essential for multiple apoptotic pathways. Nat. Genet. 20266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshida, H., H. Ichikawa, Y. Tagata, T. Katsumoto, K. Ohnishi, Y. Akao, T. Naoe, P. P. Pandolfi, and I. Kitabayashi. 2007. PML-retinoic acid receptor α inhibits PML IV enhancement of PU.1-induced C/EBPɛ expression in myeloid differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 275819-5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhong, S., P. Salomoni, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2000. The transcriptional role of PML and the nuclear body. Nat. Cell Biol. 2E85-E90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.