Abstract

The natural product salicylihalamide is a potent inhibitor of the Vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase), a potential target for antitumor chemotherapy. We generated salicylihalamide-resistant tumor cell lines typified by an overexpansion of lysosomal organelles. We also found that many tumor cell lines upregulate tissue-specific plasmalemmal V-ATPases, and hypothesize that tumors that derive their energy from glycolysis rely on these isoforms to maintain a neutral cytosolic pH. To further validate the potential of V-ATPase inhibitors as leads for cancer chemotherapy, we developed a multigram synthesis of the potent salicylihalamide analog saliphenylhalamide.

As products of evolution, natural products are selected for interaction with living systems. As such, an unbiased quest to study their function will inevitably lead to discoveries in biology, potentially with therapeutic implications.1 By accessing congeners for mode-of-action studies, optimization of potency and pharmacokinetic, toxicological, and metabolic properties, synthesis takes center stage as an enabling tool to execute a natural product-based discovery and development program.2 Herein, we report our efforts to validate inhibition of the Vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase), the target of salicylihalamide, as a strategy for cancer chemotherapeutic intervention. This program led to the selection and multigram synthesis of a salicylihalamide analog saliphenylhalamide (2, SaliPhe).

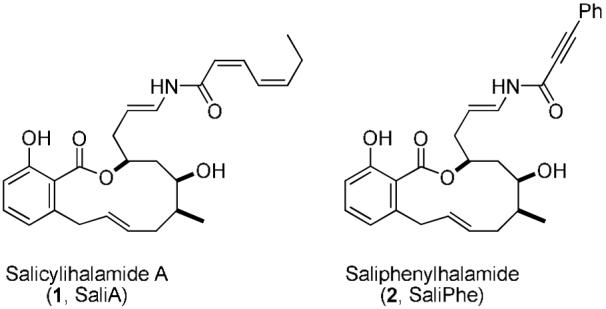

The marine metabolite salicylihalamide A (1),3 the first member of a family of marine and terrestrial metabolites characterized by a signature N-acyl-enamine appended macrocyclic salicylate, has elicited a great deal of interest from the synthetic community4 - certainly due in part because of their growth-inhibitory activities against cultured human tumor cells and oncogene-transformed cell lines through mechanisms distinct from standard clinical antitumor agents.5 The cellular target of SaliA remained elusive until after our first total synthesis,3b when Boyd and coworkers reported that SaliA and other related benzolactone enamides inhibit V-ATPase activity in membrane preparations of mammalian cells, but not V-ATPases from yeast and other fungi - an observation that distinguishes them from previously identified V-ATPase inhibitors.6 Our biochemical studies utilizing a reconstituted, fully purified bovine brain V-ATPase confirmed this activity and demonstrated that SaliA binds irreversibly to the trans-membranous proton-translocating domain via N-acyl iminium chemistry.7 Structure-activity relationship studies revealed that a macrocyclic benzolactone with a hydrophobic N-acyl enamine side-chain is essential for potent V-ATPase inhibition and cytotoxic activity, with SaliPhe (2) equipotent to SaliA.4a,b, 8

Although V-ATPases have been extensively explored as a therapeutic target to treat osteoporosis, many lines of evidence support the notion that they represent a potential target for treating solid tumors that grow in a hypoxic and acidic micro-environment.9 Increased V-ATPase activity is postulated to be required for the efficient and rapid removal of protons generated by increased rates of glycolysis.9b,c Maintaining a slightly basic cytosolic pH protects the cytoplasm from acidosis and prevents apoptosis, and acidification of the extracellular environment promotes invasion,10 metastasis, immune suppression11 and resistance to radiation and chemotherapy.9 Proper V-ATPase function is also crucial for the execution of the autophagic pathway, which has been implicated as a protective mechanism in cancer.12 To demonstrate that inhibition of V-ATPase activity is related to the toxicity induced by salicylihalamide, we have created various drug-resistant cell lines by culturing human melanoma cells (SK-MEL-5) in increasing concentrations of SaliA. A cell line resistant to 100 nM of SaliA (SR100) possessed a phenotype distinguished by an increased number of acidic lysosomal organelles (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis indicated that V-ATPase subunits and lysosomal membrane proteins are strongly upregulated in this resistant cell line (Supplementary data Fig. S1). An independent derived cell line resistant to 40 nM of SaliA (SR40) also displays an increased number of larger lysosomes as compared to drug-sensitive SK-MEL-5 cells as shown by staining with antibodies specific for the lysosomal marker proteins CD63 and Lamp2 (Fig 1B). Our working hypothesis is that the more malignant tumors rely on V-ATPase activity to deal with increased acid-load from glycolysis,13 and exploit otherwise tissue-specific isoforms found on the cell surface of acid-extruding cells (osteoclasts, kidney intercalated cells, and testis acrosomes) to maintain their cytosolic pH. In support of this mechanism, we have found that the majority of a set of 28 human tumor cell lines of different origin over-express such plasmalemmal isoforms as determined by RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 2, the plasmalemmal V-ATPase E2-subunit (ATP6V1E2) is highly expressed in cancer cell lines, but not in the normal fibroblast cell lines IMR-90 and BJ. In normal human tissues, expression of this subunit is highly enriched in the testis where it functions to acidify the acrosome.14

Figure 1.

A) Parental SK-MEL-5 cells cultured in the absence of drug and SaliA-resistant cells growing in 100 nM SaliA (SR100) were stained with the pH-sensitive dye Lysotracker Green (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The dye accumulates in acidic organelles, which are few and small in the parental SK-MEL-5 cells (top left panel), and numerous and swollen in SR100 cells (bottom left panel). B) Parental SK-MEL-5 cells and a drug-resistant line grown continually in 40 nM SaliA (SR40) were stained with antibodies to the lysosomal proteins CD63 (top panels) or Lamp2 (bottom panels) followed by labeling with a secondary antibody conjugated to an Alexa 488 fluorescent dye. The drug resistant line shows increased numbers of larger lysosomal vesicles (right panels) versus the parental SK-MEL-5 cell line (left panels).

Figure 2.

ATP6V1E2 gene expression is highly enriched in the human testis (top panel) and is also highly expressed in many human tumor cell lines (middle and bottom panels) as determined by RT-PCR. S9 ribosomal RNA served as a control for amplification.

An analog of saliA, saliphenylhalamide (SaliPhe, 2) was selected for further preclinical evaluation based on (1) in vitro cytotoxicity and V-ATPase inhibitory activity comparable to SaliA4b; (2) stability and ease of synthesis; and (3) its differential effects on normal and tumorigenic human mammary epithelial cells.16 As shown in Table 1, SaliPhe is a potent antiproliferative agent with activity against a wide variety of human tumor cell lines. There was no difference between the concentrations of SaliPhe required to inhibit the growth of MCF-7 or MCF-7/Dox cells, the latter of which are resistant to doxorubicin and other chemotherapeutic agents that are substrates for P-glycoprotein (Supplementary data Table S1). Remarkably, we observed a correlation between the resistance of selected human tumor cell lines to radiation and their corresponding sensitivity to pharmacological treatment with SaliPhe. That is, cells that are more resistant to radiation are more sensitive to SaliPhe (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that cells with higher V-ATPase activity are radioresistant.12a Furthermore, SaliPhe is also able to sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapy17 and radiation (Supplementary data Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Growth inhibitory activity of SaliPhe (2) against a panel of human tumor cell lines

| Cell Line | IC50 (nM) | Cell Line | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hep-G2b | 79.2±8.9 | MG-63e | 448.6±33.4 |

| SK-HEP-1b | 40.7±5.8 | AsPC-1f | 75.9±11.3 |

| HCT-116c | 69.3±4.9 | Panc-1f | 123.6±36.9 |

| HCT-15c | 100.1±10.8 | MCF-7g | 155.5±22.8 |

| HT-29c | 89.9±10.6 | MCF-7/Doxg | 160.0±3.3 |

| SW-480c | 424.6±73.2 | MDA-MB-231g | 179.8±57.4 |

| SK-MEL-5d | 105.9±9.6 | NCI-H460h | 52.9±6.9 |

| SK-MEL-28d | 98.5±17.2 | NCI-H1299h | 77.2±13.1 |

| A2058d | 153.9±14.9 | A549h | 145.6±2.1 |

| HOSe | 48.8±5.7 | SK-MES-1h | 76.4±32.2 |

IC50 values are average ± standard deviation of three experiments.

Cancer Type (CT) = liver.

CT = colon.

CT = melanoma.

CT = osteosarcoma.

CT = pancreas.

CT = breast.

CT = lung.

Figure 3.

The indicated cancer cell lines were treated with a range of doses of SaliPhe or radiation and the dose of radiation (Gy) or the concentration of SaliPhe (nM) required to inhibit growth by 50% was calculated. The radiation IC50 values are an average of 5 experiments and the SaliPhe IC50 values are an average of 3 experiments (Table 1). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the radiation IC50 values. The SD for the SaliPhe IC50 values can be found in Table 1.

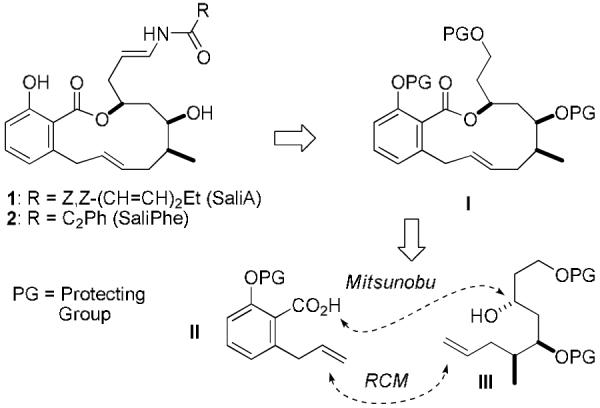

In order to further evaluate these promising anticancer activities in appropriate animal models and perform rigorous preclinical toxicology and pharmacokinetic studies, we needed to develop a scalable synthesis of SaliPhe. Our published route to salicylihalamide and analogs was based on the assembly of the 12-membered benzolactone I via a Mitsunobu esterification of alcohol III with ortho-substituted salicylic acid derivative II, followed by an E-selective ring-closing olefin metathesis. After installation of the side-chain and final deprotection, SaliPhe (2) was obtained in 23 steps from commercial available starting materials (longest linear sequence) with an overall yield of 8%.4b We have now developed a more convergent route to the more challenging fragment III, and optimized the final steps of our total synthesis. These efforts culminated in a scalable total synthesis delivering 2.54 g of SaliPhe in 15-17 steps (longest linear sequence) with an improved overall yield of 9.5% (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaH, 4-MeOBnCl, THF (76%); (b) SO3·pyridine, DMSO, NEt3, CH2Cl2 (85%); (c) LiNH2BH3, THF (99%); (d) (COCl)2, DMSO, NEt3, CH2Cl2 (91%); (e) 4, Cy2BCl, NEt3, Et2O, 0 °C → -78 °C, add 6; MeOH, pH 7 buffer, H2O2 (93%); (f) TBSCl, imidazole, cat. DMAP, DMF (95%); (g) Me2AlCl, Bu3SnH, CH2Cl2 (86%); (h) DIAD, Ph3P, THF (82%); (i) 9 mol% PhCHRu(PCy3)2(Cl)2, CH2Cl2; (j) K2CO3, MeOH (30% for 2 steps); (k) TBSCl, imidazole, cat. DMAP, DMF (95%); (l) DDQ, CH2Cl2/H2O (18:1) (92%); (m) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2 (95%); (n) (EtO)2P(O)CH2CO2CH2CHCH2, NaH, THF, 0 °C → rt (96%); (o) 10 mol% Pd(PPh3)3, morpholine, THF (97%); (p) (PhO)2PN3, NEt3, benzene (90%); (q) 15, benzene, reflux; then concentrate, dissolve in THF and add to LiCCPh in THF, -78 °C (90%); (r) HF·pyridine, pyridine, THF, rt.

The new synthesis of fragment III (alcohol 9 in Scheme 2) is based on a convergent aldol reaction between methyl ketone 4 and homochiral α-methyl-substituted aldehyde 6. Ketone 4 and aldehyde 6 are available in 2 steps each from commercially available 1,3-butanediol and known (-)-pseudoephedrine-derived amide 5.18 Addition of the dicyclohexylboronate ester derived from ketone 4 to homochiral aldehyde 6 delivered aldol product 7 in high yield (93%, 10.8 g) but low selectivity for the desired anti-Felkin diastereomer (57:43).19 The use of homochiral diisopinocampheyl enolboranes did not improve the selectivity and moreover resulted in lower yields due to competing reduction of the β-hydroxy ketone product 7 to the corresponding diol.20 The mixture of β-hydroxyketones 7 was silylated (→ 8) followed by syn-selective ketone reduction to alcohol 9 and corresponding 3S,5S-diastereomer (86% yield, 17.1 g). Mitsunobu esterification21 of the diastereomeric alcohol mixture 9 with ortho-allyl-substituted salicylic acid derivative 1022 was followed by a ring-closing olefin metathesis.23,24 At this point, methanolysis of the crude benzolactone mixture (11 and 11′) enabled a facile chromatographic removal of all unwanted stereoisomers (12′) and yielded 5.3 g of the desired lactone 12 as a single pure stereoisomer (25% yield from stereoisomer mixture 9).

The final steps of the synthesis, the introduction of the essential N-acyl enamide side-chain, follow along the lines of our published total synthesis.4b Silylation of the phenol, oxidative deprotection of the p-methoxybenzyl ether, and Dess-Martin periodinane25 oxidation to the aldehyde set the stage for a highly Z-selective Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons homologation to afford α,β-unsaturated allyl ester 13 in 80% yield (4.8 g) for the 4 step sequence. Palladium(0)-catalyzed de-allylation (→ 14) and acylazide formation performed very reproducibly on large scale, delivering 4.1 g of Curtius rearrangement precursor 15 in 87% yield for the 2 step sequence. Addition of the isocyanate derived from refluxing acylazide 15 in benzene to a -78°C solution of lithium phenylacetylide afforded 4.04 g of bis-silyl protected SaliPhe 16. Final deprotection with a buffered solution of HF·pyridine completed the synthesis of 2.54 g of SaliPhe 2.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that inhibition of vacuolar ATPase activity is responsible for the potent antiproliferative activity of the natural product salicylihalamide. We have further provided data that indicate the potential for V-ATPase inhibitors as cancer chemotherapeutic leads. A potent analog of salicylihalamide A, saliphenylhalamide, was selected for further evaluation and was prepared in multigram quantities via total synthesis. These studies highlight the power of synthetic chemistry as an enabling tool for implementing a natural product-based discovery and development program.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of salicylihalamides: synthetic strategy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (CA 90349 and CA 95471), the Robert A. Welch Foundation, and Merck Research Laboratories for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1(a).Newman DJ, Cragg GM, Snader KM. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:1022. doi: 10.1021/np030096l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Butler MS. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:2141. doi: 10.1021/np040106y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dixon N, Wong LS, Geerlings TH, Micklefield J. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:1288. doi: 10.1039/b616808f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson RM, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8329. doi: 10.1021/jo0610053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3(a).Erickson KL, Beutler JA, Cardellina JH, II, Boyd MR. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8188. doi: 10.1021/jo971556g. correction: J. Org. Chem.2001, 66, 1532.(b) For a structural revision, see:Wu Y, Esser L, De Brabander JK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:4308. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001201)39:23<4308::AID-ANIE4308>3.0.CO;2-4.

- 4(a).For total syntheses of salicylihalamide, see 3b and:Wu Y, Seguil OR, De Brabander JK. Org. Lett. 2000;2:4241. doi: 10.1021/ol0068086.Wu Y, Liao X, Wang R, Xie X-S, De Brabander JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3245. doi: 10.1021/ja0177713.Snider BB, Song F. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1817. doi: 10.1021/ol015822v.Labrecque D, Charron S, Rej R, Blais C, Lamothe S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2645.Fürstner A, Dierkes T, Thiel OR, Blanda G. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:5286. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011217)7:24<5286::aid-chem5286>3.0.co;2-g.Smith AB, III, Zheng J. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6455.Herb C, Bayer A, Maier ME. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:5649. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400617.Formal total syntheses:Yadav JS, Sundar P, Reddy R. Synthesis. 2007:1070.Holloway GA, Huegel HM, Rizzacasa MA. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:2200. doi: 10.1021/jo026798h.Haack T, Haack K, Diederich WE, Blackman B, Roy S, Pusuluri S, Georg GI. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7592. doi: 10.1021/jo050750x.

- 5(a).Reviews:Yet L. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:4283. doi: 10.1021/cr030035s.Beutler JA, McKee TC. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:787. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457827.Bowman EJ, Bowman BJ. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2005;31:29. doi: 10.1023/a:1005403427848.

- 6.Boyd MR, Farina C, Belfiore P, Gagliardi S, Kim J-W, Hayakawa Y, Beutler JA. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297:114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie X-S, Padron-Perez D, Liao X, Wang J, Roth MG, De Brabander JK. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebreton S, Xie X-S, Ferguson D, De Brabander JK. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:9635. [Google Scholar]

- 9(a).Reviews:Farina C, Gagliardi S. Drug Discov. Today. 1999;4:163. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(99)01321-5.Sennoune SR, Luo D, Martinez-Zaguilan R. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2004;40:185. doi: 10.1385/CBB:40:2:185.Fais S, De Milito A, You H, Qin W. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1805.Forgac M. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:917. doi: 10.1038/nrm2272.

- 10.For an in vitro and in vivo study of the antimetastatic potential of a small-molecule V-ATPase inhibitor, see:Supina R, Petrangolini G, Pratesi G, Tortoreto M, Favini E, Dal Bo L, Farina C, Zunino F. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.128587.

- 11.Lardner A. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001;69:522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12(a).Paglin S, Hollister T, Delohery T, Hackett N, McMahill M, Sphicas E, Domingo D, Yahalom J. Canc. Res. 2001;61:439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kroemer G, Jäättelä M. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:886. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R, Kondo S. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:726. doi: 10.1038/nrc1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:961. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su Y, Zhou A, Al-Lamki RS, Karet FE. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imai-Senga Y, Sun-Wada GH, Wada Y, Futai M. Gene. 2002;289:7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The double bond geometry of the dienamide side chain of SaliA is hard to control and maintain,4b and SaliA does suffer from decomposition upon storage (neat or DMSO solutions).

- 16.At 100 nM concentration, SaliPhe inhibited the growth of the tumorigenic human mammary epithelial cell line HME50-T (95% growth inhibition) without affecting the growth of the parent (isogenic) human mammary epithelial cell line HME-50, whereas SaliA indiscriminatory inhibited the growth of both cell lines (75% and 60% respectively @ 100 nM). We thank G. Dikmen and G. Gellert in the laboratory of J. Shay (Department of Cell Biology, UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas) for performing these experiments. For a reference on the generation of the tumorigenic HME50-T cell line from the isogenic HME50 cell line, see:Herbert B-S, Gellert GC, Hochreiter A, Pongracz K, Wright WE, Zielinska D, Chin AC, Harley CB, Shay JW, Gryaznov SM. Oncogene. 2005;24:5262. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208760.

- 17.In a genome-wide synthetic lethal RNAi screen, V-ATPase was identified as a target that specifically reduces cell-viability of a human non-small-cell lung cancer line (NCI-H1155) in the presence of otherwise sublethal concentrations of paclitaxel. Exposure to SaliPhe, paclitaxel, or a combination of these agents revealed a significant collaborative impact on cell viability in the same cancer cell line, see:Whitehurst AW, Bodemann BO, Cardenas J, Ferguson D, Girard L, Peyton M, Minna JD, Michnoff C, Hao W, Roth MG, Xie X-J, White MA. Nature. 2007;446:815. doi: 10.1038/nature05697.

- 18(a).Prepared in 2 steps (90-95% yield, 98-99% de) from (-)-pseudoephedrine according to:Myers AG, Yang BH, Chen H, McKinstry L, Kopecky DJ, Gleason JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6496.Fettes A, Carreira EM. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:9274. doi: 10.1021/jo034964v.

- 19(a).For the discovery and a detailed discussion on the “pentenyl aldehyde” effect on the stereochemical outcome of aldol reactions, see:Harris CR, Kuduk SD, Balog A, Savin KA, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2267.Lee CB, Wu Z, Zhang F, Chappell MD, Stachel SJ, Chou T-C, Guan Y, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5249. doi: 10.1021/ja010039j.

- 20.Paterson I, Goodman JM, Lister MA, Schumann RC, McClure CK, Norcross RD. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:4663. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsunobu O. Synthesis. 1981:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soltani O, De Brabander JK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1696. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.In agreement with observations made in our original salicylihalamide total synthesis,4b Grubbs’ first generation ruthenium alkylidene pre-catalyst [PhCHRu(Cl)2(PCy3)2] provided the highest E/Z-ratio (∼8-9:1).

- 24.Trnka TM, Grubbs RH. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:18. doi: 10.1021/ar000114f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dess DB, Martin JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7277. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.