Abstract

The histone H3 demethylase Ndy1/KDM2B protects cells from replicative senescence. Changes in the metabolism of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important for establishing senescence, suggesting that Ndy1 may play a role in redox regulation. Here we show that Ndy1 protects from H2O2-induced apoptosis and G2/M arrest and inhibits ROS-mediated signaling and DNA damage, while knockdown of Ndy1 has the opposite effects. Consistent with these observations, whereas Ndy1 overexpression promotes H2O2 detoxification, Ndy1 knockdown inhibits it. Ndy1 promotes the expression of genes encoding the antioxidant enzymes aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase (Aass), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1 (Nqo1), peroxiredoxin-4 (Prdx4), and serine peptidase inhibitor b1b (Serpinb1b) and represses the expression of interleukin-19. At least two of these genes (Nqo1 and Prdx4) are regulated directly by Ndy1, which binds to specific sites within their promoters and demethylates promoter-associated histone H3 dimethylated at K36 and histone H3 trimethylated at K4. Simultaneous knockdown of Aass, Nqo1, Prdx4, and Serpinb1b in Ndy1-expressing cells to levels equivalent to those detected in control cells was sufficient to suppress the Ndy1 redox phenotype.

Replicative senescence results primarily from the activation of the DNA damage response, which can be induced by telomere shortening, the aberrant firing of replication origins, activated oncogenes, or oxidative stress. Molecules that inhibit senescence, therefore, may either protect from DNA damage or interfere with the activation of the DNA damage response (3). Earlier studies from this laboratory identified the histone H3 demethylase Ndy1 (Not dead yet-1) as a physiological inhibitor of replicative senescence. Thus, overexpression of Ndy1 promotes immortalization, and knockdown of Ndy1 promotes senescence, of mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) in culture (29). Given that replicative senescence may be a feature of the response to DNA damage, these findings raised the question of whether Ndy1 protects from DNA damage by regulating redox homeostasis and/or the cellular response to oxidative stress.

Oxidation and reduction are coupled processes, which in biological systems are aided by enzymes collectively known as oxidoreductases (22). The coupled process of oxidation/reduction frequently gives rise to charged reactive radicals, known collectively as reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS is an inclusive term for oxygen anions and radicals such as superoxide (.O2−) and hydroxyl radicals (OH.), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nitric oxide (NO.), and various peroxides (ROOR.) (23, 45). ROS are produced in living cells by a variety of mechanisms: electrons escaping from the respiratory chain in mitochondria target oxygen to form .O2− (26), while NADPH oxidase and related enzymes produce .O2− upon activation, and nitric oxide synthase produces NO., .O2−, and H2O2 (30, 37). Besides the endogenous sources of ROS, there are also exogenous sources, such as environmental pollutants, cigarette smoke, and various toxins and drugs.

ROS have a short half-life. Inactivation of ROS depends on small antioxidant molecules that undergo oxidation by reacting with ROS and on the enzymatic activities of oxidoreductases. For example, superoxide dismutase converts .O2− into the less-reactive H2O2, and the latter is inactivated by catalase, peroxiredoxins, and glutathione peroxidases (35). The overall levels of ROS in a given cell are determined by the balance between the rate of production and the rate of conversion (33). ROS produced in response to external signals may function as second messengers by causing reversible chemical modifications of signaling molecules such as transcription factors, protein kinases, and phosphatases (24, 35). Most relevant as a second messenger among ROS is H2O2, which is relatively stable and diffuses easily across biological membranes. Although the functions of some ROS are physiologically important, persistence of ROS is generally harmful. Their toxicity is due to irreversible oxidation of a variety of macromolecules, such as DNA, lipids, and proteins (45).

In this paper we addressed the question of whether Ndy1 protects cells from oxidative stress. After showing that Ndy1 is indeed protective, we examined the potential mechanism of this phenotype. First, we demonstrated a significant increase in the antioxidant activity of extracts derived from cells overexpressing Ndy1. Subsequently, we showed that Ndy1 regulates the expression of a set of redox-regulatory genes and that the deregulation of these genes by Ndy1 overexpression or knockdown is sufficient to reproduce the Ndy1 redox phenotype. At least two of these genes (Nqo1 and Prdx4) appear to be direct targets of Ndy1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, expression constructs, retroviral infections, and transfections of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs).

MEFs from 13.5-day-old wild-type C57BL/6 embryos were cultured using standard conditions. Wild-type Ndy1 (Ndy1.myc) or a JmjC domain or CXXC motif deletion mutant (Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc or Ndy1-ΔCXXC.myc, respectively), C-terminally tagged with the myc epitope, was cloned into the pBabe-puro retroviral vector by standard procedures (29).

Retroviral constructs were packaged via cotransfection with pEco-pak into 293T cells. Primary MEFs at passage 0 to 1 were infected in the presence of 10 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) and were selected for 2 days in puromycin (2.5 μg/ml; Sigma). MEFs generated from independent infections were analyzed for Ndy1 expression by probing Western blots of cell lysates with an anti-myc monoclonal antibody (MAb).

MEFs were transiently transfected with an Ndy1 siRNA, which effectively reduces the expression of Ndy1 by more than 90%, or with a siRNA control (29), by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Thirty-six hours later, cells were analyzed for Ndy1 expression and were used for the experiments described in Results.

In addition, wild-type Ndy1 tagged with the myc epitope was cloned first between two loxP sites and subsequently into the retroviral vector MigR1 upstream of the gene encoding green fluorescent protein. MEFs were infected as described above and sorted 48 h later. To abolish Ndy1.myc expression, cells were infected with a pBabe-based construct of the Cre recombinase.

The Ndy1.myc MEFs were transiently transfected with aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase (Aass), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1 (Nqo1), peroxiredoxin-4 (Prdx4), and serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor clade b, member 1b (serpinb1b) siRNAs (Ambion), alone or in combination, after titration of the amount of the siRNAs (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) required to downregulate the expression of the respective genes to their levels in vector-transduced cells.

Assays of intracellular ROS levels and antioxidant activity.

Cells were pretreated with 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-DCFDA), dihydroethidium (DHE), or MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (MitoROS) (Invitrogen) in fresh Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium without phenol red at a final concentration of 10 μM, 5 μM, or 2 μM, respectively. Then cells were treated with H2O2 for 20 min and analyzed by flow cytometry (DakoCytomation).

Total cell antioxidant capacity was measured using the Antioxidant assay kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

MTT assay, TUNEL assay, and cell cycle analysis.

The 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Invitrogen) assay was carried out as previously described (13). Results were confirmed by microphotography and direct counting of cells using a standard hemocytometer.

Apoptosis was measured using a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) kit (Roche) (9).

The cell cycle distribution of MEFs was determined as previously described (12). H2O2-treated and untreated cells were trypsinized, pelleted at 1,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min, and lysed in lysis-staining buffer (3.4 mM sodium citrate, 10 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 75 μM ethidium bromide [EtBr]) (1 ml/106 cells on ice). The fluorescence intensity of cell nuclei was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), RT2 Profiler PCR array system, and immunoblotting.

Purification of total-cell RNA and first-strand cDNA synthesis were performed with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and the RETROscript kit (Ambion), respectively. PCRs were performed in triplicate in a 25-μl final volume containing template cDNA, iQ Sybr Green supermix (Bio-Rad), and specific primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Antioxidant gene expression profiling was performed using the real-time PCR array from SuperArray.

Western blots of cell lysates were probed with specific antibodies by following standard procedures.

Antibodies.

The antibodies used in this study were MAbs against phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase (phospho-AMPK) (MAb 2535), phospho-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (phospho-p38MAPK) (MAb 9215), phospho-Jun N-terminal protein kinases (phospho-JNKs), cleaved caspase-3 (MAb 9664), K36me2 (MAb 9758), and myc tag (MAb 2276) (Cell Signaling), an anti-tubulin MAb (T5168; Sigma), an anti-8-oxoguanine MAb (MAB3560; Millipore), an anti-Nqo1 polyclonal antibody (sc-25591; Santa Cruz), and an anti-Prdx4 MAb (ab16943; Abcam). The production of an anti-Ndy1 polyclonal antibody has been described previously (29).

Single-cell gel electrophoresis assay and 8-oxo-dG levels.

DNA damage was measured using the CometAssay (Trevigen). MEFs plated in 12-well culture plates were harvested 45 min after treatment with H2O2. Harvested cells were suspended in molten low-melting-point agarose and spread onto the CometSlide. Cells were lysed, and following alkaline gel electrophoresis, they were stained with Sybr green I. Fluorescent Sybr green I-bound DNA was photographed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope with a 20× objective and a Spot charge-coupled-device camera (Diagnostic Instruments). To measure DNA damage, the comet tail intensity and length were quantified using Comet Assay IV software (Perceptive Instruments).

To measure the levels of 8-oxo-dG, MEFs were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, either before or 30 min after treatment with H2O2, and stained with an anti-8-hydroxyguanine antibody. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides, with Vectashield mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Labs). Images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope with a 10× objective and a Spot charge-coupled-device camera. Images were quantified as red/blue ratios by using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc.).

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using the Chromatin Immunoprecipitation assay kit (Stratagene) as described by the manufacturer. Histones were cross-linked to DNA by formaldehyde. Cells were lysed and sonicated to shear DNA to 300- to 500-bp fragments. A fraction of each sample was then precleared with protein A- and salmon sperm DNA-bound agarose beads. Following overnight incubation with the immunoprecipitating antibody (anti-myc or anti-histone H3 dimethylated at K36 [anti-H3K36me2]) and 1 h of incubation with protein A- and agarose-salmon sperm DNA beads at 4°C, the immunoprecipitates were subjected to multiple washes. DNA recovered after reversion of the histone-DNA cross-links with NaCl was incubated with proteinase K. Subsequently, it was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. Real-time PCR using different sets of primers (see Tables S3, S4, and S5 in the supplemental material) to amplify the Nqo1, Prdx4, and Prdx2 genes was employed in both the input and the immunoprecipitated DNA.

Statistical analysis.

The significance of variability between data sets was determined by using the unpaired t test. Each experiment included triplicate measurements for each condition tested, unless otherwise indicated. All results were expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) and are based on measurements from at least three independent experiments, unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

Ndy1 promotes resistance to H2O2-induced oxidative stress.

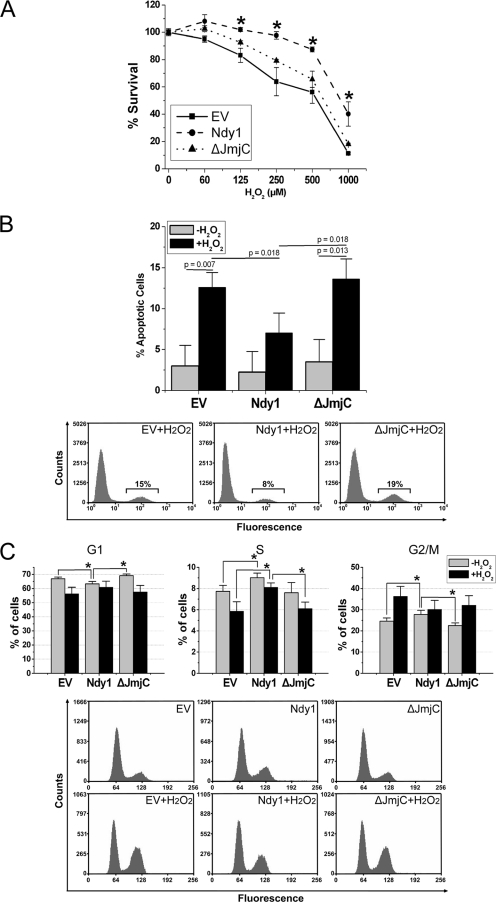

Our earlier studies had shown that Ndy1 is a physiological inhibitor of senescence in dividing cells (29). Given that one of the main factors promoting senescence is DNA damage induced by ROS (3), we examined whether the overexpression or knockdown of Ndy1 modulates cellular resistance to oxidative stress. The expression levels and the localization of wild-type Ndy1 and the Ndy1 mutants used in this study are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. To measure the relative number of live cells in cultures of MEFs infected with the empty pBabe-puro retrovirus vector or with pBabe-puro-based constructs of Ndy1 and Ndy1-ΔJmjC, before and after treatment with H2O2,, we used the MTT assay. In parallel experiments, we used the TUNEL assay to examine the rate of apoptosis of the same cells and EtBr staining of the nuclear DNA and flow cytometry to address their cell cycle distribution. The results (Fig. 1A) revealed that Ndy1- but not Ndy1-ΔJmjC-expressing cells are resistant to oxidative stress. Specifically, Ndy1 protects from H2O2-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1B) and cell cycle arrest (Fig. 1C). The percentages of cells in G1 and S after treatment with H2O2 are higher in Ndy1-transduced cells than in cells transduced with an empty vector or Ndy1-ΔJmjC, probably due to the fact that Ndy1 inhibits arrest in G2/M. Microphotography of the same cells (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) was in agreement with the data discussed above in that it showed that Ndy1 inhibits the toxicity of H2O2. Untreated Ndy1-expressing cultures are characterized by a slight but significant decrease in the percentage of cells in G1 and slight but significant increases in the percentages of cells in S and G2/M.

FIG. 1.

Ndy1 overexpression renders MEFs resistant to oxidative stress. (A) Cell viability as determined by the MTT assay. MEFs transduced with an Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct or with the empty retroviral vector (EV) were treated with different concentrations of H2O2 for 12 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Data are mean percentages of live cells ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). (B) Apoptosis as determined by the TUNEL assay. MEFs transduced with an Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct or with the EV were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). The rates of apoptosis in H2O2-treated and untreated cells harvested 1 h later were determined by TUNEL staining and flow cytometry. (Top) Data are mean percentages of apoptotic cells ± SEM and are derived from five independent experiments. (Bottom) Representative plots of FACS analysis. (C) Cell cycle analysis. The DNA contents of MEFs harvested before and 12 h after treatment with H2O2 were determined. (Top) The percentages of cells in the G1 (left), S (middle), and G2/M (right) phases of the cell cycle were measured before and 12 h after treatment with H2O2 (0.5 mM). Data are the mean percentage of cells in a given phase ± the SEM and are derived from six independent experiments. (Bottom) Representative plots of FACS analysis before (upper row) and after (lower row) treatment with H2O2. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

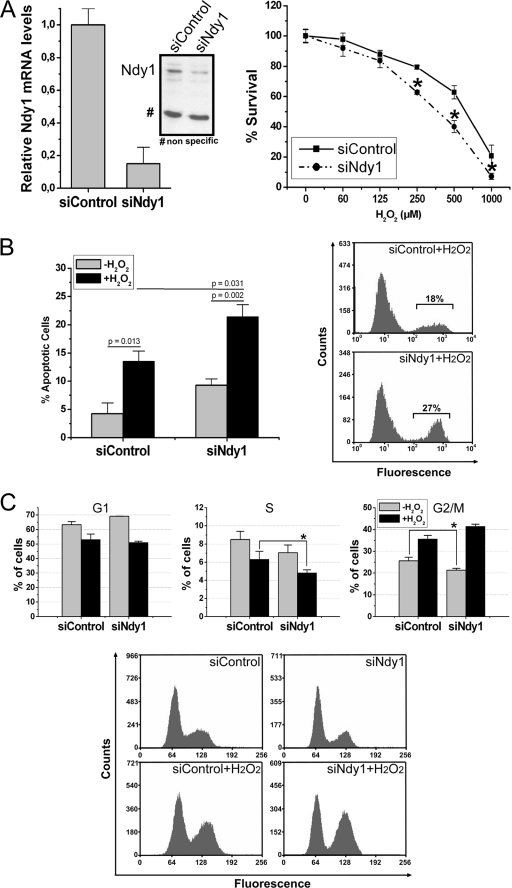

These data revealed that Ndy1 overexpression inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative stress by a JmjC domain-dependent process. To determine whether endogenous Ndy1 is a physiological redox regulator, we repeated these experiments with MEFs transfected with Ndy1 siRNA. Transfection of Ndy1 siRNA downregulated the expression of Ndy1 by about 90%, as measured by real-time RT-PCR and verified by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). The transfected cells were treated with H2O2, and their responses were monitored with the MTT (Fig. 2A) and TUNEL (Fig. 2B) assays and with EtBr nuclear staining and flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). The results showed that knocking down Ndy1 sensitizes the cells to H2O2-induced oxidative stress, suggesting that endogenous Ndy1 is indeed a physiological regulator of the cellular response to oxidative stress. The cell cycle distribution of cells not treated with H2O2 (Fig. 2C) exhibits a pattern opposite that of cells engineered to overexpress Ndy1. These data, combined, are in agreement with our earlier findings showing that Ndy1-expressing cells growing under physiological conditions exhibit slightly accelerated growth (29). The protective role of Ndy1 raised the question whether the levels of Ndy1 were affected by H2O2. MEFs were treated with H2O2, and the levels of Ndy1 were monitored at different time points by real-time RT-PCR. The results showed that Ndy1 expression is decreased by 50% 3 h after treatment with H2O2. However, by 12 h, the Ndy1 levels had more than doubled relative to the levels prior to exposure to H2O2 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 2.

Ndy1 knockdown enhances sensitivity to oxidative stress. (A) Cell viability as determined by the MTT assay. MEFs transfected with Ndy1 siRNA (siNdy1) or scrambled siRNA (siControl) were treated with different concentrations of H2O2 for 12 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Data are mean percentages of live cells ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). (B) Apoptosis as determined by the TUNEL assay. MEFs transfected with siNdy1 or siControl were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM), subjected to TUNEL staining 1 h later, and analyzed by FACS. (Left) Data are mean percentages of apoptotic cells ± SEM and are based on five independent experiments. (Right) Representative plots of FACS analyses. (C) Cell cycle analysis. The DNA contents of MEFs harvested before and 12 h after treatment with H2O2 were determined. (Top) The percentages of cells in the G1 (left), S (middle), and G2/M (right) phases of the cell cycle were measured before and 12 h after treatment with H2O2. Data are the mean percentage of cells in a given phase ± the SEM and are derived from six independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). (Bottom) Representative plots of FACS analysis before (upper row) and after (lower row) treatment with H2O2.

Ndy1 inhibits ROS-dependent signaling in MEFs.

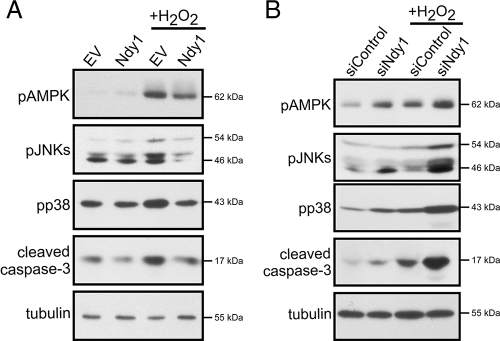

ROS and, more importantly, H2O2 function as second messengers by inducing reversible chemical modifications in signaling molecules (24, 33, 35). Thus, oxidative stress activates AMPK by promoting its phosphorylation at Thr172 (43). In addition, it activates JNK and p38MAPK by promoting their phosphorylation at Thr183/Tyr185 and Thr180/Tyr182, respectively (2). Finally, it promotes the activation of caspase-3 resulting from cleavage adjacent to Asp175, leading to apoptosis (43). We therefore examined the phosphorylation of AMPK, JNK, and p38MAPK and the cleavage of caspase-3 in MEFs infected with the Ndy1 retroviral construct or with the empty vector, both before and after treatment with H2O2. The results (Fig. 3A) showed that overexpression of Ndy1 inhibits the phosphorylation of AMPK, JNK, and p38MAPK and the cleavage of caspase-3 both before and after treatment with H2O2. Knocking down Ndy1 with siRNA had the opposite effect (Fig. 3B), reinforcing the conclusion that Ndy1 is a physiological regulator of H2O2 accumulation in MEFs.

FIG. 3.

Ndy1 expression modifies the signaling response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress. (A) MEFs transduced with the pBabe-puro-based retroviral construct Ndy1.myc or with the empty retroviral vector (EV) were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). Lysates of H2O2-treated and untreated cells harvested 2 h later were analyzed by Western blotting for the phosphorylation of redox-sensitive signaling proteins. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) MEFs transfected with Ndy1 siRNA (siNdy1) or scrambled siRNA (siControl) were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). Lysates of H2O2-treated and untreated cells harvested 2 h later were analyzed by Western blotting for the phosphorylation of redox-sensitive signaling proteins. The data are representative of three independent experiments. Notably, no effect on the total levels of these proteins was observed.

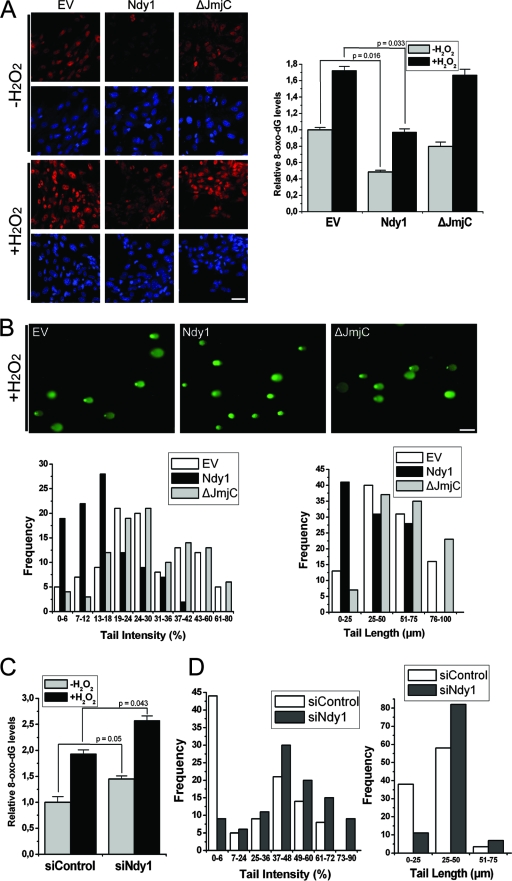

Ndy1 inhibits the oxidation of deoxyguanosine and DNA damage.

ROS oxidize deoxyguanosine to form 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG). The incorporation of 8-oxo-dG into DNA is the most common oxidative DNA lesion. 8-oxo-dG forms base pairs with adenine and is excised via the mismatch repair or the base excision repair system. If it is not excised, it gives rise to G-to-T transversions (6, 7, 15, 38).

To determine whether Ndy1 inhibits the accumulation of 8-oxo-dG in cellular DNA, we stained MEFs overexpressing Ndy1 or Ndy1-ΔJmjC, and transfected with Ndy1 or control siRNA, with an antibody specific for 8-oxo-dG, and we monitored the staining by immunofluorescence. The results revealed that wild-type Ndy1 inhibits (Fig. 4A) and Ndy1 siRNA promotes (Fig. 4C; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) the accumulation of 8-oxo-dG in cellular DNA. This finding suggested that Ndy1 may decrease oxidative DNA damage. To address this hypothesis, we employed the comet assay, which detects the accumulation of single- and double-stranded DNA breaks (44). The results confirmed that wild-type Ndy1 indeed inhibits the accumulation of DNA damage induced by H2O2 (Fig. 4B) and that knocking down endogenous Ndy1 has the opposite effect (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Ndy1 expression inhibits deoxyguanosine oxidation and DNA damage. (A) Deoxyguanosine oxidation. MEFs transduced with an Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct or with the empty retroviral vector (EV) were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). H2O2-treated and untreated cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence 30 min later for 8-oxo-dG accumulation. The ratio of red (8-oxo-dG) to blue (DAPI) staining was quantified for each sample. The ratio was given the arbitrary value of 1 in untreated EV cells, which were used as the basis for all comparisons. (Left) Representative microphotography of 8-oxo-dG and DAPI staining of H2O2-treated and untreated cells. Bar, 50 μm. (Right) Cumulative data are presented as the means of the relative 8-oxo-dG levels ± SEM and are based on three independent experiments. (B) DNA damage. MEFs transduced with an Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct or with the EV were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). H2O2-treated and untreated cells were subjected to single gel electrophoresis 45 min later. Following electrophoresis, samples were stained with Sybr green and scored by fluorescence microscopy. (Top) Representative microphotographs of Sybr green-stained samples. Bar, 100 μm. (Bottom) DNA damage, defined by the intensity and length of the comet tails, was quantified using Comet Assay IV image analysis software. Data are expressed as percentages of cells with a given level of DNA damage reflected in the intensity (left) or length (right) of the tail. Data are based on three independent experiments. (C) Deoxyguanosine oxidation. MEFs transfected with Ndy1 siRNA (siNdy1) or with scrambled siRNA (siControl), were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). H2O2-treated and untreated cells were analyzed 30 min later for 8-oxo-dG accumulation. The ratio of red (8-oxo-dG) to blue (DAPI) staining was quantified for each sample. The ratio in untreated cells transfected with siControl, which were used as the basis for all comparisons, was given the arbitrary value of 1. Cumulative data are presented as the means of the relative 8-oxo-dG levels ± SEM and are based on two independent experiments. (D) DNA damage. MEFs transfected with siNdy1 or with siControl were treated with H2O2 (0.25 mM), subjected to single-cell gel electrophoresis, stained with Sybr green, and scored by fluorescence microscopy. DNA damage, defined by the intensity and length of the comet tails, was quantified using Comet Assay IV image analysis software. Data are expressed as percentages of cells with a given level of DNA damage reflected in the intensity (left) and length (right) of the tail. Data are based on two independent experiments.

Ndy1 inhibits the accumulation of H2O2 in both H2O2-treated and untreated cells.

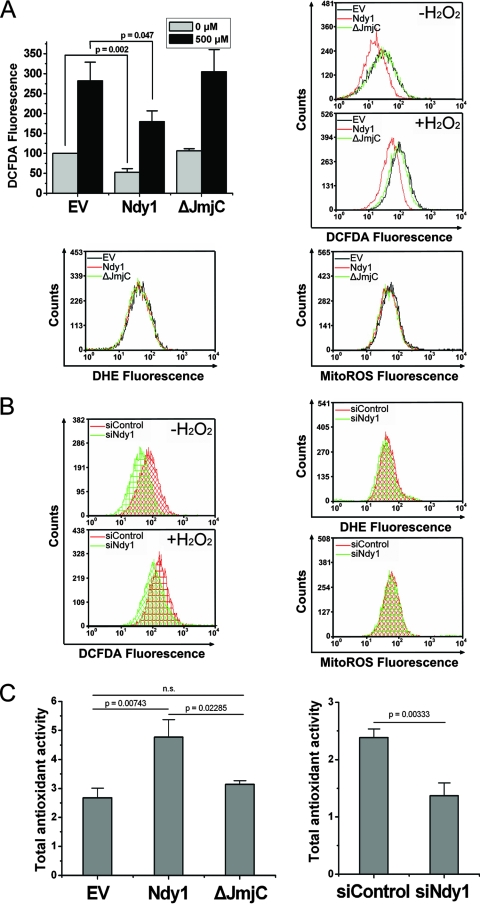

The data showing that Ndy1 modulates ROS-dependent signaling, 8-oxo-dG incorporation into cellular DNA, and oxidative DNA damage suggested that Ndy1 may inhibit the accumulation of H2O2, and perhaps other ROS, rather than the cellular response to H2O2. To directly address this hypothesis, Ndy1, Ndy1-ΔJmjC, or empty vector cells were stained with carboxy-DCFDA, DHE, or MitoROS before and 20 min after treatment with H2O2 and were analyzed by flow cytometry. The same experiments were repeated with MEFs transfected with Ndy1 or control siRNAs. DCFDA fluoresces when exposed to H2O2, and DHE fluoresces when exposed to .O2− (11). MitoROS targets the mitochondria and fluoresces when exposed to mitochondrially localized ROS (14). The results (Fig. 5A) showed that overexpression of Ndy1, but not that of Ndy1-ΔJmjC, inhibits the accumulation of H2O2 both before and after treatment with H2O2. However, Ndy1 overexpression does not affect the accumulation of .O2−. Finally, no differences in ROS were detected with MitoROS, suggesting that Ndy1 did not affect the accumulation of ROS in the mitochondria (Fig. 5A; see also Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Knocking down Ndy1 had the opposite effects (Fig. 5B), suggesting that endogenous Ndy1 is indeed a physiological regulator of cellular H2O2 levels. The regulation of H2O2 levels by Ndy1 explains the effects of Ndy1 overexpression or knockdown on ROS-dependent signaling (Fig. 3). The conclusion from the data in Fig. 3 and 5 is that the lower levels of H2O2 in cells overexpressing Ndy1 are below the activation threshold of ROS-dependent signaling pathways, particularly the JNK pathway. To determine whether the inhibition of spontaneous H2O2 accumulation by Ndy1 was passage dependent, we used DCFDA to measure cellular H2O2 levels in sequentially passaged MEFs. The results (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material) revealed that whereas H2O2 levels remain low in later passages in Ndy1-expressing cells, they do increase with passage in empty vector- and Ndy1-ΔJmjC-expressing cells.

FIG. 5.

Ndy1 expression regulates the intracellular levels of H2O2 in H2O2-treated and untreated cells. (A) ROS levels in cells overexpressing Ndy1. MEFs transduced with an Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct or with the empty vector (EV) were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). H2O2-treated and untreated cells were stained with ROS indicators (DCFDA, DHE, and MitoROS) and analyzed by FACS. (Top left) Cumulative data from six experiments are presented as mean DCFDA fluorescence ± SEM. EV cell fluorescence was given the arbitrary value of 100. (Top right) Representative overlay plots of DCFDA-stained cells analyzed by FACS. (Bottom) DHE (left) and MitoROS (right) staining. Untreated cells are shown. (B) ROS levels in cells in which Ndy1 was knocked down. MEFs transfected with Ndy1 siRNA (siNdy1) or with scrambled siRNA (siControl) were treated with H2O2 (0.5 mM). H2O2-treated and untreated cells were stained with ROS indicators (DCFDA, DHE, and MitoROS) and analyzed by FACS. (Left) Representative overlay plots of DCFDA-stained cells analyzed by FACS. Similar data were obtained in four independent experiments. (Right) DHE (top) and MitoROS (bottom) staining. Untreated cells are shown. There was no difference between samples before and after treatment with H2O2. (C) (Left) Total antioxidant activity in cells overexpressing Ndy1 and in cells in which Ndy1 was knocked down. Extracts from MEFs transduced with the Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct or with the EV were analyzed for their capacities to detoxify H2O2 compared to Trolox. (Right) The antioxidant capacities of lysates of MEFs transfected with siNdy1 or with siControl were measured as in the left panel. In both panels, cumulative data were derived from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Ndy1 enhances the antioxidant activity of cells.

The fact that Ndy1 inhibits cellular H2O2 accumulation in H2O2-treated cells suggests that it may enhance the ability of the cells to neutralize H2O2. To address this question, lysates of MEFs transduced with the Ndy1 retroviral constructs described above were analyzed for their antioxidant activity by using the Antioxidant assay kit. The same experiment was repeated with MEFs transfected with Ndy1 and control siRNAs. The results (Fig. 5C, left) showed that cells expressing Ndy1, but not Ndy1-ΔJmjC, exhibit enhanced antioxidant activity. Knocking down Ndy1 had the opposite effect (Fig. 5C, right), suggesting that indeed Ndy1 is a physiological regulator of the antioxidant activity of cells.

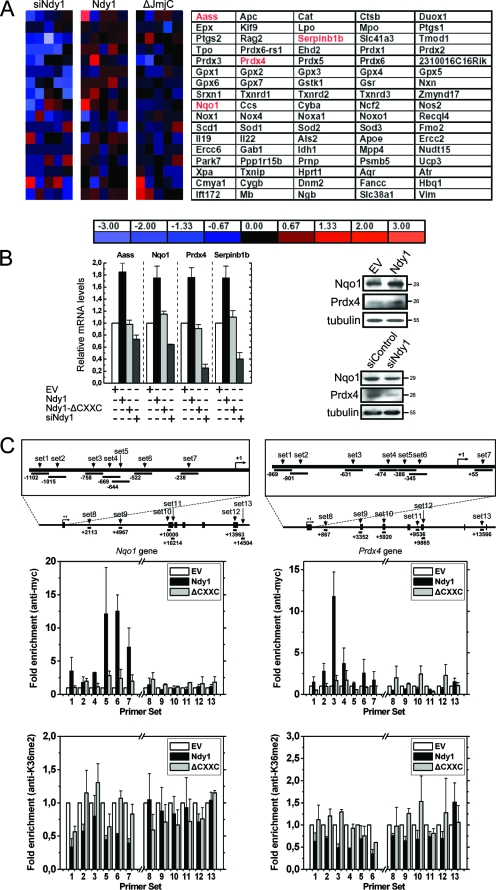

Ndy1 regulates the expression of antioxidant genes.

The findings described above suggested that Ndy1 may regulate the expression of genes that control the neutralization of H2O2. To address this question, we interrogated the expression of 85 oxidative stress and antioxidant defense genes in MEFs transduced with the retroviral constructs described above, using a quantitative RT-PCR array that includes genes encoding catalase, glutathione peroxidases, and peroxiredoxins, which neutralize cellular H2O2 (27). This analysis (Fig. 6A) identified five genes whose expression was deregulated in Ndy1-expressing but not in Ndy1-ΔJmjC-expressing cells. Four of these genes, Aass, Nqo1, Prdx4, and Serpinb1b, were upregulated, and one, Interleukin-19 (IL-19), was downregulated. To confirm these findings, we reexamined the expression of these genes by using real-time RT-PCR. The data (Fig. 6B, left) confirmed that both the overexpression and the knockdown of Ndy1 deregulate these genes by driving their expression in opposite directions. Western blot analysis of lysates harvested from the same cells (Fig. 6B, right) confirmed that the protein products of at least two of these genes (Nqo1 and Prdx4) were also upregulated by Ndy1. These data were verified by comparing the expression of Nqo1 and Prdx4 in MEFs transduced with the floxed Ndy1 retroviral construct pMigR1LoxP.Ndy1.LoxP and superinfected with a Cre retroviral construct, which promotes the deletion of the exogenous Ndy1 gene, with MEFs superinfected with the empty vector (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). The regulation of Nqo1 and Prdx4 by Ndy1 is further supported by experiments showing that H2O2 upregulates the expression of Ndy1 in MEFs and that the expression of Nqo1 and Prdx4 parallels the expression of Ndy1 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 6.

Ndy1 regulates the expression of antioxidant genes. (A) Real-time RT-PCR array of antioxidant genes. Results are expressed as mean changes (n-fold) in mRNA levels in cells transduced with the Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔJmjC.myc retroviral construct relative to empty vector (EV)-transduced cells and in cells transfected with siRNA for Ndy1 (siNdy1) relative to scrambled siRNA (siControl). Notably, no differences between EV and siControl cells were observed. The genes that were further analyzed are highlighted in red. (B) Real-time RT-PCR and Western blot analysis verified the data obtained from the array. (Left) Results are expressed as mean changes (n-fold) in mRNA levels in cells transduced with Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔCXXC.myc relative to EV-transduced cells and in cells transfected with siNdy1 relative to siControl-transfected cells. Cumulative data from two independent experiments performed in triplicate are shown. The expression of all genes tested was given the arbitrary value of 1 in EV-transduced cells, which were used as the basis for all comparisons. No differences were observed between EV and siControl cells. (Right) Western blots of lysates of Ndy1- or EV-transduced cells and siNdy1- or siControl-transfected cells were probed with antibodies to Nqo1, Prdx4, or tubulin (loading control). (C) ChIP analysis. (Top) Schematic diagrams of the topology of the primer sets used for the Nqo1 and Prdx4 genes. (Center and bottom) ChIP analyses of MEFs transduced with the Ndy1.myc or Ndy1-ΔCXXC.myc retroviral construct or with the EV were performed using monoclonal antibodies against the myc tag (center) and histone H3 dimethylated K36 (bottom). Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were quantified using real-time PCR and the indicated sets of primers. Data from three independent experiments are expressed as mean enrichment of a given DNA fragment in ChIPs of experimental cells relative to control cells, where the level of immunoprecipitated DNA was given the arbitrary value of 1. Ndy1 binding and histone H3K36me2 levels were also examined by ChIP in the negative-control Ndy1-insensitive gene Prdx2 (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material).

These data raised the question of whether the regulation of antioxidant genes by Ndy1 is direct. To address this question, we carried out ChIP assays focusing on the binding of Ndy1 to the promoter regions of two of the genes, Nqo1 and Prdx4. The experiment was performed with MEFs transduced with wild-type Ndy1 and Ndy1-ΔCXXC constructs or with the empty vector. The data (Fig. 6C, top) showed that whereas Ndy1 binds defined regions in the promoters of both genes, the ΔCXXC mutant does not. In agreement with these data, wild-type Ndy1 induced the activation of an Nqo1-luciferase reporter, while the ΔCXXC mutant did not (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). Ndy1 functions as a histone demethylase. However, its specificity is uncertain, with evidence supporting its ability to demethylate either H3K36me2 (42) or histone H3 trimethylated at K4 (H3K4me3) (8). Studies from this laboratory suggest that Ndy1 is primarily a histone H3K36me2 demethylase and that its H3K4me3 demethylase activity is weak (S. Kampranis et al., unpublished data). To determine, therefore, whether Ndy1 bound to these genes functions as a histone demethylase (42), we focused our studies on histone H3K36me2. The ability of Ndy1 to demethylate histone H3K36me2 in vivo was confirmed by quantitative immunofluorescence assays and flow cytometry (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). ChIP assays showed that the levels of histone H3K36me2 associated with both promoters were lower in cells expressing wild-type Ndy1 than in empty vector-transduced cells (Fig. 6C, bottom). As a negative control in these experiments, we used Prdx2, an Ndy1-unresponsive gene. The results showed that Ndy1 does not bind to the Prdx2 promoter and does not affect the levels of histone H3K36me2 in the same promoter (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). Similarly, the ΔCXXC mutant of Ndy1, which does not bind the promoters of Nqo1 and Prdx4, did not alter the methylation status of histone H3K36me2 associated with either promoter (Fig. 6C, bottom) and did not upregulate the expression of these genes (Fig. 6B, left; see also Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). As a result, it did not inhibit the accumulation of H2O2, either before or after treatment with H2O2, and it did not protect cells from oxidative stress (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that Ndy1 is a direct regulator of at least these two antioxidant genes and that it functions by binding their promoters and demethylating histone H3K36me2. Since there is evidence that Ndy1 also demethylates histone H3K4me3 (8), we addressed via ChIP the effects of Ndy1 overexpression on the abundance of histone H3K4me3 associated with the same promoters. These experiments showed that H3K4me3 levels were marginally lower in these promoters (data not shown) in cells overexpressing Ndy1. However, additional studies will be needed to confirm these data.

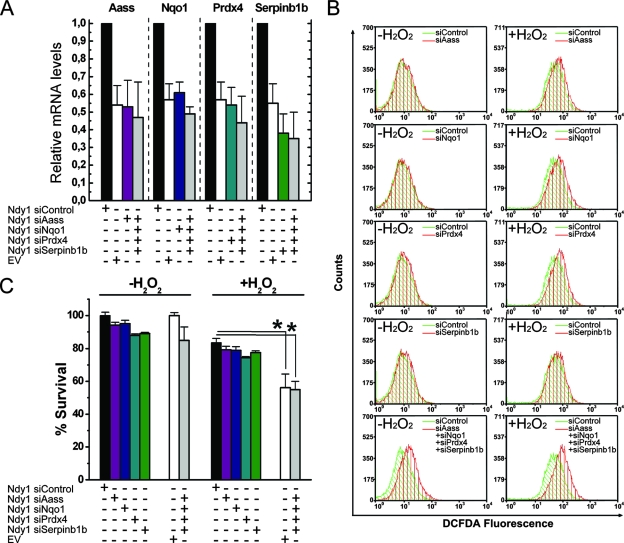

The deregulation of antioxidant genes by Ndy1 is sufficient to induce resistance to the oxidative-stress phenotype.

At least three of the ROS-regulatory genes (Aass, Nqo1, and Prdx4) upregulated by Ndy1 play a direct role in redox homeostasis. Aass is a tetrameric enzyme that is involved in the oxidative degradation of lysine. Different domains of the enzyme posses lysine-ketoglutarate reductase and saccharopine dehydrogenase activities and catalyze the first two steps in lysine degradation, leading to the formation of l-glutamate and 2-aminiadipic-2-semialdehyde. The latter functions as an electron donor and undergoes oxidation to 2-aminoadipic acid (17, 21, 32). Nqo1 is a ubiquitous homodimeric flavoprotein that is localized in the cytosol and catalyzes the two-electron reduction of quinones to hydroquinones. This reaction prevents the one-electron reduction of quinones, which leads to the generation of superoxide and its derivative H2O2. As a result, inhibition of Nqo1 enhances the production of superoxide and H2O2 in living cells, and upregulation of Nqo1 has the opposite effects (4, 27). Finally, peroxiredoxins convert H2O2 and alkyl-hydroperoxides to H2O or alcohols, respectively. The six peroxiredoxins are classified into three groups: 2-Cys (Prdx1 to -4), atypical 2-Cys (Prdx5), and 1-Cys (Prdx6). Of the members of the 2-Cys group, Prdx1 and Prdx2 are localized in the cytosol, Prdx3 is localized in the mitochondria, and Prdx4 is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and the extracellular space (34, 35, 46).

The fourth gene upregulated by Ndy1, Serpinb1b, and IL-19, which is downregulated by Ndy1, play indirect roles in redox homeostasis. Serpinb1b is an inhibitor of the neutrophil serine proteases, elastase, cathepsin-G, and proteinase-3. By blocking the activity of these proteases, Serpinb1b is strongly anti-inflammatory (1). Thus, studies with animal models have shown that Serpinb1b inhibits pulmonary inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (1, 48). Serpinb1b inhibits the accumulation of ROS, perhaps indirectly by inhibiting inflammation. More important, intracellular serpins provide important survival functions by abolishing lysosome-dependent cell death upon different stressful treatments, such as oxidative stress (20). IL-19 is a glycosylated peptide with an apparent molecular size of 35 to 40 kDa that belongs to the class 2 α-helical cytokine family and binds both the IL-19 and IL-20 receptors (28).

The data described above raised the question of whether the oxidative stress phenotype induced by Ndy1 is the result of Ndy1-induced deregulation of these ROS-regulatory genes. To address this question, we proceeded to determine whether the downregulation of the genes upregulated by Ndy1 to levels equivalent to those observed in empty-vector-infected cells restores cellular H2O2 levels and cellular susceptibility to oxidative stress in Ndy1-expressing cells. To address this question, we first titrated the amount of siRNA sufficient to downregulate the expression of each of the four genes described above to levels similar to those observed in empty-vector-infected control cells. Subsequently, each of these siRNAs was transfected into MEFs either alone or in combination. Following confirmation by real-time RT-PCR of the knockdown of each of these genes to the desired levels (Fig. 7A), the cells were treated with H2O2, and 12 h later, they were measured using the MTT assay. The levels of H2O2 were also measured by DCFDA staining and flow cytometry. The results showed that knocking down all four genes together to levels similar to those detected in empty vector cells restores cellular H2O2 levels (Fig. 7B) and cellular susceptibility to oxidative stress (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that the downregulation of H2O2 by Ndy1 and the resistance to oxidative stress may be mediated by the effects of Ndy1 on the expression of Aass, Prdx4, Nqo1, and Serpinb1b.

FIG. 7.

Downregulation of the Ndy1-regulated antioxidant genes in Ndy1-overexpressing MEFs to the levels of control cells restores cellular sensitivity to H2O2. (A) Titration of target gene knockdown. siRNAs targeting the Ndy1-regulated genes were titrated in Ndy1-overexpressing cells to knock down these genes to the levels in empty vector (EV) cells. siRNAs were transfected separately or in combination, and their effects on the expression of each gene relative to siControl-transfected and EV cells were recorded. The levels of all genes in the siControl-transfected cells were given the arbitrary value of 1. Data from three independent experiments are expressed as mean RNA levels relative to those in siControl cells ± SEM. (B) H2O2 levels in Ndy1-expressing cells transfected with siRNAs of Ndy1 target genes. MEFs transduced with Ndy1 were transfected with each of the four siRNAs alone or in combination, stained with carboxy-DCFDA, and analyzed by FACS. Representative FACS analysis plots from three independent experiments are shown. (C) Survival of Ndy1-expressing cells transfected with siRNAs of Ndy1 target genes. MEFs transduced with Ndy1 transfected with each of the four siRNAs, alone or in combination, were treated with H2O2 for 12 h. Relative numbers of live cells were measured using the MTT assay. Data are mean percentages of live cells ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this paper we presented evidence that Ndy1 renders cells resistant to oxidative stress. Specifically, Ndy1 protects cells from H2O2-induced apoptosis and G2/M arrest. Interestingly, even in the absence of exogenous H2O2, cells engineered to overexpress Ndy1 exhibited greater viability and higher levels of proliferation, suggesting that perhaps Ndy1 also promotes resistance to the endogenous baseline levels of ROS. Knocking down Ndy1 had the opposite effects, suggesting that resistance to oxidative stress is a physiological function of Ndy1.

Resistance to oxidative stress could be caused by Ndy1-mediated downregulation of the cellular levels of ROS or by Ndy1-mediated resistance to the toxic effects of ROS. The deleterious effects of ROS are attributed to the sustained activation of stress-activated kinases, the promotion of caspase-3 cleavage, and consequent cell death (16, 43). Therefore, we reasoned that changes in the phosphorylation status of ROS-regulated proteins by Ndy1 suggest that the latter regulates ROS levels. The data presented in this report support this hypothesis by showing that Ndy1 overexpression inhibits, and Ndy1 knockdown promotes, the phosphorylation of AMPK, JNK, and p38MAPK both before and after treatment with H2O2. Further support for this hypothesis was provided by data showing that both the incorporation of 8-oxo-dG into cellular DNA and the accumulation of DNA damage were inhibited by Ndy1. The latter findings provided a molecular explanation for the results of earlier studies also suggesting that Ndy1 may protect cells from DNA damage. These studies included an siRNA screen of Caenorhabditis elegans, which identified the nematode ortholog of Ndy1 as a gene that interferes with the accumulation of spontaneous mutations (31), and a yeast-based assay showing that the mammalian Ndy1 homolog may also promote genomic integrity (41).

The suggested downregulation of ROS in cells overexpressing Ndy1 and upregulation in cells in which Ndy1 was knocked down were confirmed with assays that measure ROS directly. Interestingly, these studies demonstrated that of the different species of ROS, the primary target of Ndy1 is H2O2, which is also known to play an important role as a second messenger (5, 33, 35) and which, in the presence of Fe3+ or Cu2+, can be converted to toxic OH.. Further studies revealed that the downregulation of H2O2 by Ndy1 was due to increased neutralization rather than decreased production.

The deregulation of H2O2 neutralization in cells in which Ndy1 was either overexpressed or knocked down was linked to changes in the expression of Aass, Nqo1, Prdx4, Serpinb1b, and IL-19. The first four of these genes were upregulated, while IL-19 was downregulated, in cells overexpressing Ndy1. Knocking down Ndy1 had the opposite effects, suggesting that Ndy1 is a physiological regulator of these genes. Two of the genes, Nqo1 and Prdx4, were shown to be direct Ndy1 targets. First, Ndy1 but not its ΔCXXC mutant was shown to bind specific regions in the promoters of both genes. Second, whereas Ndy1 upregulated their expression, the ΔCXXC mutant did not, suggesting that binding to the promoter region is necessary for their induction. Finally, whereas the wild-type Ndy1 construct activated the mouse Nqo1 promoter, the ΔCXXC mutant of Ndy1 did not. The changes observed in the expression of Aass, Nqo1, Prdx4, and Serpinb1b were sufficient to induce the oxidative-stress phenotype of Ndy1 overexpression. The data in this report showing that Ndy1 functions as an activator of transcription are in agreement with recently published data showing that Ndy1 promotes the transcriptional activation of the Hoxd1 gene (47). Other studies, however, have shown that Ndy1 functions as a transcriptional repressor (8, 10, 39). We conclude that Ndy1, like other epigenetic regulators (36), may function either as a repressor or as an activator of transcription.

Earlier studies had shown that Ndy1 is a histone H3 demethylase. Originally it was thought that it demethylates histone H3 dimethylated at K36 (42). However, recent studies suggested that it might preferentially demethylate H3 trimethylated at K4 (8). We therefore used ChIP assays to examine the methylation status of histone H3 associated with the Nqo1 and Prdx4 genes at both K36 and K4. The results showed a significant reduction in K36-dimethylated histone H3 associated with the promoters of both genes in cells engineered to overexpress Ndy1 but not its CXXC deletion mutant. Trimethylation of histone H3 at K4 was also reduced in the promoter regions of both genes, though in a spatially restricted manner that spared the region near the transcription start site. However, the effect of Ndy1 on histone H3K4 trimethylation was weak, and additional work will be needed to assess its significance. Additional ChIP assays failed to show binding of Ndy1 or changes in the methylation status of histone H3 at K4 and K36 within regions near the 5′ end, the middle, and the 3′ end of both genes. These data are consistent with observations suggesting that Ndy1 is a direct inducer of Nqo1 and Prdx4. First, K36me2 of promoter-associated histone H3 represses transcription (18, 40). Second, acetylation of H3 at K36, a modification that is associated with enhancement of transcription, is in direct competition with H3 methylation at the same site (25). Consistent with these observations, Set2, a K36 histone H3 methyltransferase, acts as a transcriptional repressor if mistargeted to promoters (18, 40). Therefore, whereas K36 dimethylation of histone H3, which is associated with the body of active genes, facilitates productive full-length transcription (19), the same modification represses transcription if targeted to promoter regions. We conclude that the binding of Ndy1 to the promoters of the Nqo1 and Prdx4 genes and the subsequent local demethylation of H3K36me2 may stimulate transcription.

Our data on the role of Ndy1 in the expression of antioxidant genes raised the question of whether the upregulation of these genes in cells overexpressing Ndy1 is sufficient to downregulate H2O2 and to induce resistance to the oxidative-stress phenotype. Partial concerted knockdown of all four genes upregulated by Ndy1 to levels similar to those in vector-transduced cells fully neutralized the antioxidant effects of Ndy1 and reversed the Ndy1-induced resistance to oxidative stress. These findings confirmed that the combined upregulation of Aass, Nqo1, Prdx4, and Serpinb1b is sufficient to induce the Ndy1 redox phenotype.

The data in this report raise questions about the role of Ndy1 in oncogenesis. The protection from oxidative-stress-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest is expected to promote oncogenesis by facilitating the expansion of the target cells and by allowing established tumor cells to grow under conditions of stress. However, Ndy1, which interferes with the accumulation of mutations that drive oncogenesis, may also function as a tumor suppressor. The possibility that it may have a pro-oncogenic role is supported by our earlier findings showing that it is a target of provirus integration and is upregulated in retrovirus-induced rodent lymphomas (29) and by findings showing that it is overexpressed in breast cancer and B- and T-cell lymphomas and leukemias in humans (http://source.stanford.edu). The possibility that Ndy1 may also function as a tumor suppressor is supported by findings showing that its expression in glioblastomas exhibits an inverse correlation with tumor aggressiveness (8). We propose that Ndy1 may function either as an oncogene or as a tumor suppressor gene, depending on the cellular context.

In summary, the data in this report showed that Ndy1 epigenetically regulates several redox genes and that the regulation of these genes by Ndy1 is responsible for the modulation of H2O2 levels and for the resistance of Ndy1-expressing cells to oxidative stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Tzatsos, S. Kampranis, H. Leighton Grimes, and P. Hinds for helpful discussions. We also thank Phil Hinds for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 CA 109747. C.P. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Fellow.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 October 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benarafa, C., G. P. Priebe, and E. Remold-O'Donnell. 2007. The neutrophil serine protease inhibitor serpinb1 preserves lung defense functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J. Exp. Med. 2041901-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benhar, M., I. Dalyot, D. Engelberg, and A. Levitzki. 2001. Enhanced ROS production in oncogenically transformed cells potentiates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and sensitization to genotoxic stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 216913-6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collado, M., M. A. Blasco, and M. Serrano. 2007. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell 130223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen, J. J., M. M. Hinkhouse, M. Grady, A. W. Gaut, J. Liu, Y. P. Zhang, C. J. Weydert, F. E. Domann, and L. W. Oberley. 2003. Dicumarol inhibition of NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase induces growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer via a superoxide-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 635513-5520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Autréaux, B., and M. B. Toledano. 2007. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8813-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeWeese, T. L., J. M. Shipman, N. A. Larrier, N. M. Buckley, L. R. Kidd, J. D. Groopman, R. G. Cutler, H. te Riele, and W. G. Nelson. 1998. Mouse embryonic stem cells carrying one or two defective Msh2 alleles respond abnormally to oxidative stress inflicted by low-level radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9511915-11920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earley, M. C., and G. F. Crouse. 1998. The role of mismatch repair in the prevention of base pair mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9515487-15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frescas, D., D. Guardavaccaro, F. Bassermann, R. Koyama-Nasu, and M. Pagano. 2007. JHDM1B/FBXL10 is a nucleolar protein that represses transcription of ribosomal RNA genes. Nature 450309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gavrieli, Y., Y. Sherman, and S. A. Ben-Sasson. 1992. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 119493-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gearhart, M. D., C. M. Corcoran, J. A. Wamstad, and V. J. Bardwell. 2006. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol. Cell. Biol. 266880-6889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Govindarajan, B., J. E. Sligh, B. J. Vincent, M. Li, J. A. Canter, B. J. Nickoloff, R. J. Rodenburg, J. A. Smeitink, L. Oberley, Y. Zhang, J. Slingerland, R. S. Arnold, J. D. Lambeth, C. Cohen, L. Hilenski, K. Griendling, M. Martinez-Diez, J. M. Cuezva, and J. L. Arbiser. 2007. Overexpression of Akt converts radial growth melanoma to vertical growth melanoma. J. Clin. Investig. 117719-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimes, H. L., T. O. Chan, P. A. Zweidler-McKay, B. Tong, and P. N. Tsichlis. 1996. The Gfi-1 proto-oncoprotein contains a novel transcriptional repressor domain, SNAG, and inhibits G1 arrest induced by interleukin-2 withdrawal. Mol. Cell. Biol. 166263-6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatziapostolou, M., C. Polytarchou, P. Katsoris, J. Courty, and E. Papadimitriou. 2006. Heparin affin regulatory peptide/pleiotrophin mediates fibroblast growth factor 2 stimulatory effects on human prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28132217-32226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imoto, K., D. Kukidome, T. Nishikawa, T. Matsuhisa, K. Sonoda, K. Fujisawa, M. Yano, H. Motoshima, T. Taguchi, K. Tsuruzoe, T. Matsumura, H. Ichijo, and E. Araki. 2006. Impact of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 on insulin signaling. Diabetes 551197-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson, A. L., R. Chen, and L. A. Loeb. 1998. Induction of microsatellite instability by oxidative DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9512468-12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamata, H., S. Honda, S. Maeda, L. Chang, H. Hirata, and M. Karin. 2005. Reactive oxygen species promote TNF-α-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 120649-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasahara, T., and T. Kato. 2003. Nutritional biochemistry: a new redox-cofactor vitamin for mammals. Nature 422832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landry, J., A. Sutton, T. Hesman, J. Min, R. M. Xu, M. Johnston, and R. Sternglanz. 2003. Set2-catalyzed methylation of histone H3 represses basal expression of GAL4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 235972-5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, B., M. Gogol, M. Carey, S. G. Pattenden, C. Seidel, and J. L. Workman. 2007. Infrequently transcribed long genes depend on the Set2/Rpd3S pathway for accurate transcription. Genes Dev. 211422-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luke, C. J., S. C. Pak, Y. S. Askew, T. L. Naviglia, D. J. Askew, S. M. Nobar, A. C. Vetica, O. S. Long, S. C. Watkins, D. B. Stolz, R. J. Barstead, G. L. Moulder, D. Bromme, and G. A. Silverman. 2007. An intracellular serpin regulates necrosis by inhibiting the induction and sequelae of lysosomal injury. Cell 1301108-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markovitz, P. J., and D. T. Chuang. 1987. The bifunctional aminoadipic semialdehyde synthase in lysine degradation. Separation of reductase and dehydrogenase domains by limited proteolysis and column chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 2629353-9358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayes, P. A., and K. M. Botham. 2003. Biologic oxidation, p. 86-91. In R. K. Murray, D. K. Granner, P. A. Mayes, and V. W. Rodwell (ed.), Harper's illustrated biochemistry. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

- 23.McEligot, A. J., S. Yang, and F. L. Meyskens, Jr. 2005. Redox regulation by intrinsic species and extrinsic nutrients in normal and cancer cells. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 25261-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng, T. C., T. Fukada, and N. K. Tonks. 2002. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Mol. Cell 9387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris, S. A., B. Rao, B. A. Garcia, S. B. Hake, R. L. Diaz, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, C. D. Allis, J. D. Lieb, and B. D. Strahl. 2007. Identification of histone H3 lysine 36 acetylation as a highly conserved histone modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2827632-7640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nulton-Persson, A. C., and L. I. Szweda. 2001. Modulation of mitochondrial function by hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 27623357-23361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oppermann, U. 2007. Carbonyl reductases: the complex relationships of mammalian carbonyl- and quinone-reducing enzymes and their role in physiology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47293-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pestka, S., C. D. Krause, D. Sarkar, M. R. Walter, Y. Shi, and P. B. Fisher. 2004. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22929-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfau, R., A. Tzatsos, S. C. Kampranis, O. B. Serebrennikova, S. E. Bear, and P. N. Tsichlis. 2008. Members of a family of JmjC domain-containing oncoproteins immortalize embryonic fibroblasts via a JmjC domain-dependent process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1051907-1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porasuphatana, S., P. Tsai, and G. M. Rosen. 2003. The generation of free radicals by nitric oxide synthase. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 134281-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pothof, J., G. van Haaften, K. Thijssen, R. S. Kamath, A. G. Fraser, J. Ahringer, R. H. Plasterk, and M. Tijsterman. 2003. Identification of genes that protect the C. elegans genome against mutations by genome-wide RNAi. Genes Dev. 17443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Praphanphoj, V., K. A. Sacksteder, S. J. Gould, G. H. Thomas, and M. T. Geraghty. 2001. Identification of the alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase-phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene, the human ortholog of the yeast LYS5 gene. Mol. Genet. Metab. 72336-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reth, M. 2002. Hydrogen peroxide as second messenger in lymphocyte activation. Nat. Immunol. 31129-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhee, S. G., H. Z. Chae, and K. Kim. 2005. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 381543-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhee, S. G., S. W. Kang, W. Jeong, T. S. Chang, K. S. Yang, and H. A. Woo. 2005. Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice, K. L., I. Hormaeche, and J. D. Licht. 2007. Epigenetic regulation of normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Oncogene 266697-6714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen, G. M., P. Tsai, J. Weaver, S. Porasuphatana, L. J. Roman, A. A. Starkov, G. Fiskum, and S. Pou. 2002. The role of tetrahydrobiopterin in the regulation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase-generated superoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 27740275-40280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo, M. T., M. F. Blasi, F. Chiera, P. Fortini, P. Degan, P. Macpherson, M. Furuichi, Y. Nakabeppu, P. Karran, G. Aquilina, and M. Bignami. 2004. The oxidized deoxynucleoside triphosphate pool is a significant contributor to genetic instability in mismatch repair-deficient cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24465-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez, C., I. Sanchez, J. A. Demmers, P. Rodriguez, J. Strouboulis, and M. Vidal. 2007. Proteomics analysis of Ring1B/Rnf2 interactors identifies a novel complex with the Fbxl10/Jhdm1B histone demethylase and the Bcl6 interacting corepressor. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6820-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strahl, B. D., P. A. Grant, S. D. Briggs, Z. W. Sun, J. R. Bone, J. A. Caldwell, S. Mollah, R. G. Cook, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and C. D. Allis. 2002. Set2 is a nucleosomal histone H3-selective methyltransferase that mediates transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 221298-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki, T., K. Minehata, K. Akagi, N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2006. Tumor suppressor gene identification using retroviral insertional mutagenesis in Blm-deficient mice. EMBO J. 253422-3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukada, Y., J. Fang, H. Erdjument-Bromage, M. E. Warren, C. H. Borchers, P. Tempst, and Y. Zhang. 2006. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature 439811-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzatsos, A., and P. N. Tsichlis. 2007. Energy depletion inhibits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling and induces apoptosis via AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser-794. J. Biol. Chem. 28218069-18082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visvardis, E. E., A. M. Tassiou, and S. M. Piperakis. 1997. Study of DNA damage induction and repair capacity of fresh and cryopreserved lymphocytes exposed to H2O2 and gamma-irradiation with the alkaline comet assay. Mutat. Res. 38371-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waris, G., and H. Ahsan. 2006. Reactive oxygen species: role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. J. Carcinog. 514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood, Z. A., E. Schroder, J. Robin Harris, and L. B. Poole. 2003. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2832-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamagishi, T., S. Hirose, and T. Kondo. 2008. Secondary DNA structure formation for Hoxb9 promoter and identification of its specific binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 361965-1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yasumatsu, R., O. Altiok, C. Benarafa, C. Yasumatsu, G. Bingol-Karakoc, E. Remold-O'Donnell, and S. Cataltepe. 2006. SERPINB1 upregulation is associated with in vivo complex formation with neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G in a baboon model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 291L619-L627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.