Abstract

We tested the possibility that proteasome inhibition may reverse preexisting cardiac hypertrophy and improve remodeling upon pressure overload. Mice were submitted to aortic banding and followed up for 3 wk. The proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (0.5 mg/kg) or the vehicle was injected daily, starting 2 wk after banding. At the end of the third week, vehicle-treated banded animals showed significant (P < 0.05) increase in proteasome activity (PA), left ventricle-to-tibial length ratio (LV/TL), myocyte cross-sectional area (MCA), and myocyte apoptosis compared with sham-operated animals and developed signs of heart failure, including increased lung weight-to-TL ratio and decreased ejection fraction. When compared with that group, banded mice treated with epoxomicin showed no increase in PA, a lower LV/TL and MCA, reduced apoptosis, stabilized ejection fraction, and no signs of heart failure. Because overload-mediated cardiac remodeling largely depends on the activation of the proteasome-regulated transcription factor NF-κB, we tested whether epoxomicin would prevent this activation. NF-κB activity increased significantly upon overload, which was suppressed by epoxomicin. The expression of NF-κB-dependent transcripts, encoding collagen types I and III and the matrix metalloprotease-2, increased (P < 0.05) after banding, which was abolished by epoxomicin. The accumulation of collagen after overload, as measured by histology, was 75% lower (P < 0.05) with epoxomicin compared with vehicle. Myocyte apoptosis increased by fourfold in hearts submitted to aortic banding compared with sham-operated hearts, which was reduced by half upon epoxomicin treatment. Therefore, we propose that proteasome inhibition after the onset of pressure overload rescues ventricular remodeling by stabilizing cardiac function, suppressing further progression of hypertrophy, repressing collagen accumulation, and reducing myocyte apoptosis.

Keywords: collagen, nuclear factor-κB

the 26s proteasome is the main mechanism of degradation of intracellular proteins. It is made of two particles, the 19S cap, which binds and denatures the protein to be degraded, and the 20S core, which degrades the client protein through three proteolytic activities: trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like, and caspase-like (45). This degradation results in the production of peptides containing <20 amino acids, which will be hydrolyzed completely by cytosolic peptidases. Proteasome-mediated proteolysis has been extensively characterized in skeletal muscle, in conditions of muscle wasting, atrophy, and cachexia (8, 39, 51). However, a role for the proteasome in controlling cardiac cell mass remains largely unknown. Recent evidence shows that the proteasome may be involved in cardiac stress. For instance, several reports have shown the beneficial effects of proteasome inhibitors in preventing the damage resulting from myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (3, 32, 43). However, limited information is available about the role of the proteasome in the cardiac response to stress induced by overload.

The goal of the present study was to test whether the manipulation of proteasome activity might be a tool for the hypertrophied heart in terms of a regression of preexisting hypertrophy and prevention of cardiac remodeling. Our underlying hypothesis is that a regulation of proteasome activity participates in cardiac hypertrophy, contractile dysfunction, and ventricular remodeling following pressure overload. Several lines of evidence support that possibility. First, it was shown that proteasome expression and activity are increased at the onset of pressure overload (13). Second, it was shown recently that proteasome inhibition also prevents the prohypertrophic effect of growth agonists in isolated cardiac myocytes (23, 37). In addition, a major component of overload-induced cardiac dysfunction is the accumulation of extracellular matrix by remodeling (7, 35), which is associated with the activation of the inducible transcription factor NF-κB (17). The activity of NF-κB is regulated by the proteasome (22), and in a previous study conducted in the rat, cardiac fibroblasts showed that proteasome inhibition blocks NF-κB activation and subsequent collagen synthesis (38). Taking these observations together, proteasome inhibitors, when administered after the onset of pressure overload, could not only improve contractile function by limiting cardiac cell hypertrophy but also reverse remodeling by preventing the NF-κB-mediated accumulation of collagen. Accordingly, our objective was to examine the consequence of proteasome inhibition on cardiac function and remodeling in the overloaded heart.

METHODS

Animal model.

Experiments were performed on male, 3- to 4-mo-old 129SVJ mice. Proteasome inhibition was performed with epoxomicin (Peptide International, Louisville, KY), a specific inhibitor of the β5 protein responsible for the chymotryptic activity of the 20S core of the proteasome (30, 40). The specificity of the inhibitor is further supported by the fact that the effects of epoxomicin can be reproduced by lactacystin, another proteasome inhibitor but with a different chemical structure (13, 23). We also showed that epoxomicin does not affect chymotryptic enzymes not related to the proteasome (23). Epoxomicin was diluted in saline-10% DMSO and injected at a daily dose of 0.5 mg/kg ip for a duration of 1 wk, consistent with our previous studies (13, 23). No complications and/or side effects related to treatment with epoxomicin were observed. Controls were injected with the vehicle only. Aortic banding was performed on anesthetized mice (ketamine, 65 mg/kg; xylazine, 1.2 mg/kg; and acepromazine, 2.17 mg/kg) (13) with a 7-0-braided polyester suture tied around the aorta against a 28-gauge needle. No complication or mortality was observed after banding, and all operated mice were included in the experimental groups. Sham-operated animals underwent surgery without constriction. Left ventricular (LV) function was measured by two-dimensional echocardiography (13-MHz probe, Accuson 256). The LV-to-tibial length ratio (LV/TL) and the lung weight-to-TL ratio (LW/TL) were measured. The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, Revised 1996), and the animal protocol used in this study was approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunoblotting.

Total protein extraction was performed at 4°C in a lysis buffer containing (in mmol/l) 25 Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 150 NaCl, 15 KCl, 1 EDTA, and 1 DTT and 0.5% Triton X-100 and 5% glycerol, supplemented with protease, kinase, and phosphatase inhibitors, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. All the samples were denatured by boiling, resolved on SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to membranes. Primary antibodies were added at the recommended dilution and incubated overnight. Antibodies against the proteasome components were from Biomol (Plymouth, PA). Other antibodies were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Detection was performed by chemiluminescence.

Proteasome assay.

Proteasome activity was measured from 25 μg of total protein extracts added to 1 ml assay buffer consisting of (in mmol/l) 25 HEPES (pH 7.5) and 0.5 EDTA, containing 40 μmol/l of the fluorogenic substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (Boston Biochem, Cambridge, MA) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, in presence of different concentrations of ATP (23), followed by fluorescence measurement (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA) (4). This substrate is specific for the chymotryptic activity of the proteasome and does not interfere with the tryptic or caspase-like activities of the organelle (29). The tryptic activity was measured from 10 μg proteins incubated under the same conditions with the substrate Boc-Leu-Arg-Arg-AMC (Biomol).

NF-κB activity.

The activity of the transcription factor NF-κB was measured with the Trans AM Assay Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), an ELISA-based system that detects the binding of NF-κB to the immobilized DNA consensus binding site (16). The binding reaction was carried out for 1 h at room temperature upon the addition of 30 μg of total protein extract and in the presence of an antibody recognizing the NF-κB subunit p65. Binding activity was detected by spectrophotometry.

Histopathology.

Samples were fixed in 10% formalin and cut in 7-μm-thick sections. Tissue sections were stained with Masson's trichrome to identify extracellular matrix or with picric acid Sirius red to identify collagen (27). The surface of tissue section covered by extracellular matrix or collagen was measured on a Nikon E800 Eclipse microscope by video-based Metamorph Image analyzer system (Universal Imaging, Westchester, PA) and reported as a percentage of the total surface of the tissue section. The myocyte cross-sectional area was determined on digitized images of tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled wheat germ agglutinin-stained sections, as before (13). Myocyte outlines were traced, and the cell areas were measured using Image ProPlus Software System (Silver Springs, MD). At least 100 myocytes were measured in each region. Transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed as described (11) on sections treated with 2% H2O2 to inactivate peroxidases and with 20 μg/ml proteinase K for permeabilization. DNA fragments were labeled with 2 nM biotin-conjugated dUTP and 0.1 U/μl deoxynucleotidyl transferase for 1 h at 37°C (18). The incorporation of biotin-16-dUTP was measured with FITC-ExtrAvidin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The slides were mounted in a Vector 4′-6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) medium for fluorescent microscopic observation at a ×40-objective field. Nuclear counterstaining was performed with DAPI.

Quantitative PCR.

Specific primers and probes (derived with FAM and TAMRA) (19) were designed for the transcripts of collagen type I and collagen type III and of the matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-2 using the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Total RNA was extracted by the phenol-chloroform method using the Tri-Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) (6). For each measurement, the mRNA of interest was reverse transcribed from 60 ng of total RNA with the TaqMan RT kit (Applied Biosystems) and used for quantitative PCR (40 cycles of a 10-s step at 95°C and a 1-min step at 60°C) using the TaqMan PCR mix (Applied Biosystems) on a 7300 ABI-Prism Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems). The standards were prepared for each transcript of interest from its PCR-amplified cDNA after ligation of the T7 promoter (Ambion, Austin, TX) (12). Because of the variation in loading, transcripts were reported to cyclophilin, used as a housekeeping gene (44).

Cell culture.

Cardiac myocytes were prepared from 1-day-old Wistar rats as before (10) after digestion with 0.1% collagenase type IV (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 0.1% trypsin (Invitrogen), and 15 μg/ml DNase I (Sigma Aldrich). Cell suspensions were applied on a discontinuous Percoll gradient (1.060/1.082 g/ml) to separate cardiac myocytes from fibroblasts and other cell types in a buffer containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-F12 (1:1, Invitrogen), 17 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM glutamine, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. The myocytes were plated at a density of 106 cells/well. The purity of such preparation has been shown before (10, 20). The culture medium was changed to a serum-free medium after 24 h. The activation of caspase-3 was measured with the ApoTarget kit (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE for the number of animals indicated in each figure legend. We used the Student's t-test for two-group comparison. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni correction was used for multigroup comparison when necessary. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Proteasome activation after initiation of pressure overload.

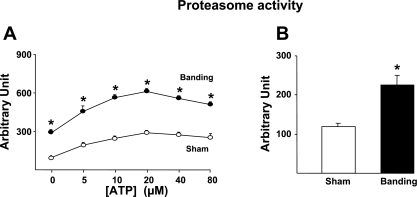

We first measured the changes in proteasome activity in response to pressure overload using total heart extracts from mice banded for 1 wk compared with sham-operated animals. Because the normal activity and assembly of the 19S and 20S proteasome subunits require energy (40), the activity assay was performed in the presence of different concentrations of ATP. As expected (41), the addition of ATP progressively increased the proteasome activity until reaching a plateau (Fig. 1A). At all concentrations of ATP, the proteasome activity was significantly higher in banded mice compared with sham-operated mice (Fig. 1A). To verify that proteasome activation during hypertrophy takes place in cardiac cells, cardiac myocytes were isolated from mice hearts subjected to 1 wk banding. As shown in Fig. 1B, cardiac myocytes showed an increased proteasome activity after banding that was comparable to the increase found in total heart extracts.

Fig. 1.

Proteasome activation by cardiac hypertrophy. Measurement after 1 wk banding. A: ATP dependence of proteasome activity in sham-operated vs. banded hearts (n = 4/group). B: increased proteasome activity in adult mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from banded hearts vs. sham-operated hearts (n = 3/group). *P < 0.01 vs. sham.

Proteasome inhibition decreases preexisting cardiac hypertrophy.

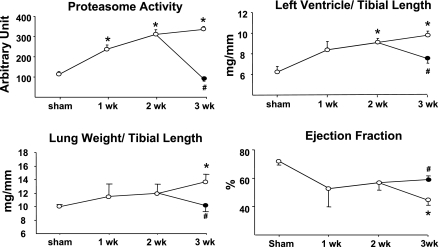

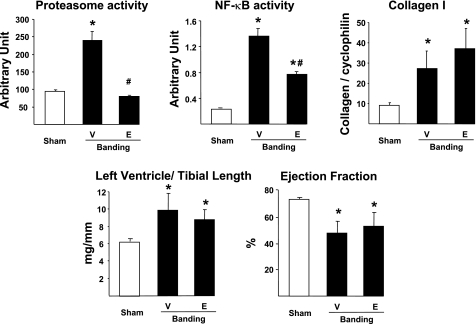

Mice were followed up to 3 wk following aortic banding to determine the dynamic adaptation of proteasome activity and cardiac structure and function in response to pressure overload. Vehicle-treated banded mice showed a progressive increase in proteasome activity together with an increase in LV/TL (6.2 ± 0.3 in sham vs. 9.9 ± 0.4 3 wk after banding; P < 0.01), reflecting cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. 2). Between the second and third week after banding, these mice also developed signs of heart failure, including an increase in LW/TL (10.0 ± 0.3 in sham vs. 13.6 ± 0.7 3 wk after banding; P < 0.01) and a decrease in ejection fraction (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proteasome inhibition regresses preexisting hypertrophy. Measurement of proteasome activity, left ventricular (LV) weight-to-tibial length and lung weight-to-tibial length ratios, and ejection fraction in hearts from mice submitted to 1, 2, or 3 wk banding and treated daily with vehicle (○) or epoxomicin (•) during the third week (n = 6/group for all panels). #P < 0.05 vs. 3 wk vehicle; *P < 0.01 vs. sham.

Based on these data, an additional group of mice was treated with the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin, initiated 2 wk after banding, the time point at which cardiac function starts to deteriorate (Fig. 2). Mice were treated for 1 wk with epoxomicin (0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip) or with the vehicle. All mice were analyzed at the end of the third week after banding. Treatment with epoxomicin suppressed the increase in proteasome activity found in hearts from banded mice compared with sham-operated mice, and it also reduced the LV/TL (Fig. 2). Further deterioration of cardiac function during the third week of overload, both in terms of LW/TL and ejection fraction, was prevented by epoxomicin treatment (Fig. 2). Therefore, epoxomicin reduces preexisting hypertrophy and stabilizes ejection fraction. We showed before (13, 23) that a 1-wk treatment with epoxomicin in sham-operated mice does not affect LV/TL, LW/TL, or ejection fraction.

Proteasome inhibition decreases morphological damage by pressure overload.

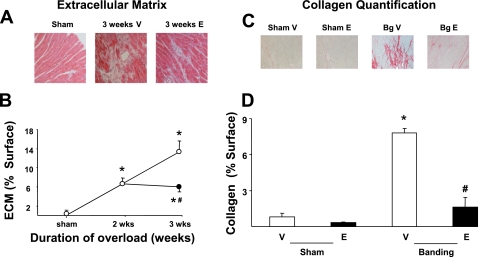

To begin elucidating the molecular mechanisms by which epoxomicin prevents the deterioration of cardiac function after banding, we first compared the morphology of hearts treated with vehicle or with the proteasome inhibitor on tissue sections stained with Masson's trichrome. When compared with sham-operated hearts, vehicle-treated banded hearts showed an accumulation of extracellular matrix that increased progressively, covering 6.6% of the myocardial cross-sectional area after 2 wk of pressure overload and 13.3% after 3 wk (Fig. 3, A and B). When epoxomicin treatment was started after 2 wk banding, a further increase in extracellular matrix accumulation was prevented (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3.

Prevention of collagen accumulation by proteasome inhibitors during pressure overload. A: Masson's trichrome staining of transversal sections of hearts submitted to 3 wk banding and treated daily with epoxomicin (E) or vehicle (V) during the last week compared with sham-operated hearts. B: accumulation of extracellular matrix (measured as a percentage of the surface of the LV tissue section) after 3 wk banding in presence of epoxomicin (•) or vehicle (○) compared with that of sham-operated animals (n = 4/group). *P < 0.05 vs. corresponding sham; #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding vehicle. C: picric acid Sirius red staining after 3 wk banding (Bg) and treatment with epoxomicin or vehicle compared with shams. D: quantification of collagen (measured as a percentage of the surface of the LV tissue section) in the same groups (n = 4/group). #P < 0.01 vs. corresponding vehicle; *P < 0.01 vs. corresponding sham.

We determined next how this accumulation of extracellular matrix relates in terms of collagen deposition. For that purpose, sections from the same hearts were stained with picric acid Sirius red to measure specifically collagen accumulation (Fig. 3C). In sham-operated animals, the amount of collagen content (quantitated under light microscopy as a percentage of cross-sectional myocardial surface) did not differ significantly between epoxomicin- and vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 3D). After 3 wk banding, collagen content increased up to eightfold in vehicle-treated animals compared with the corresponding sham-operated group (Fig. 3D), whereas treatment with epoxomicin during the last week of banding significantly (P < 0.01) reduced such accumulation to 1.5-fold (Fig. 3D).

Regulation of collagen transcripts by proteasome inhibition.

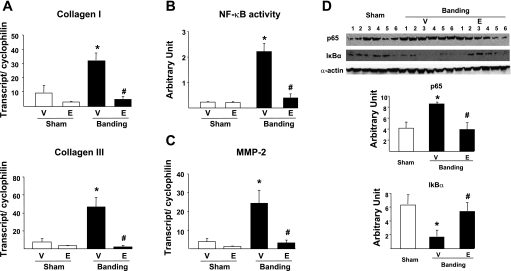

To determine how proteasome inhibition prevents collagen accumulation in the overloaded heart, we measured by quantitative PCR the expression of genes encoding collagen type I and type III. When compared with that of sham-operated animals, the expression of these genes increased by about three- to fivefold after 3 wk banding in vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 4A). However, such increase triggered by pressure overload was totally prevented in presence of epoxomicin (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Regulation of collagen transcription by proteasome inhibitors. A: quantitative PCR (qPCR) for collagen type I and III transcripts in sham-operated animals vs. 3-wk banded (Banding) mice treated with vehicle or with epoxomicin during the last week. Data are normalized per cyclophilin transcript. B: NF-κB activity measured by ELISA. C: qPCR for matrix metalloprotease-2 (MMP-2) transcript in sham-operated animals vs. 3-wk banded mice treated with vehicle or with epoxomicin during the last week. Data are normalized per cyclophilin transcript. D: protein expression of the NF-κB subunit p65 and the NF-κB inhibitor IκBα. Data are normalized per expression of α-actin. #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding vehicle; *P < 0.05 vs. sham (A–C: n = 5/group; D: n = 6/group).

We next examined which transcriptional mechanism might be involved to prevent the activation of the genes encoding collagen upon pressure overload. An important activator of collagen gene expression upon cardiac stress is the proteasome-regulated heterodimeric (p50/p65) transcription factor NF-κB (38), which is activated during myocardial hypertrophy (24, 42). After 3 wk banding, NF-κB activity was increased by 10-fold in vehicle-treated animals compared with sham-operated animals (Fig. 4B), and this was accompanied by a significant increase in the transcript level of the NF-κB-responsive gene encoding the MMP-2 (Fig. 4C). In the presence of epoxomicin, the activation of NF-κB by pressure overload was abolished (Fig. 4b), and MMP-2 transcript expression was comparable with that found in sham-operated animals (Fig. 4C).

Protein expression of the NF-κB subunit p65 was doubled upon banding in vehicle- but not in epoxomicin-treated samples (Fig. 4D). Nuclear translocation and activation of NF-κB require the simultaneous ubiquitylation and proteasome degradation of the constitutively expressed NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα (46). When compared with sham-operated hearts, vehicle-treated banded hearts showed a threefold decrease in protein expression of IκBα (P < 0.01), compatible with its degradation by the proteasome (Fig. 4D). In epoxomicin-treated banded hearts, however, IκBα protein expression was comparable with that found in sham-operated animals (Fig. 4D).

Sequential effects of proteasome inhibitors in the overloaded heart.

It could be argued that the decreased activity of NF-κB in hearts from mice treated with epoxomicin after banding is the consequence, rather than the cause, of decreased hypertrophy. To address that potential limitation, mice were treated with a single dose of epoxomicin 2 wk after banding and euthanized 24 h later. In that group, the proteasome activation induced by pressure overload was already abolished after a single injection of epoxomicin (Fig. 5). The increase in NF-κB activity was also reduced by 40–50% (Fig. 5). However, heart mass (LV/TL) and cardiac contractility (ejection fraction) were not significantly affected compared with vehicle-treated banded hearts (Fig. 5). Similarly, collagen transcript expression was unchanged compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5). Therefore, the reduction of NF-κB activity upon epoxomicin treatment following overload precedes any change in heart mass and remodeling and is not a mere consequence of decreased hypertrophy.

Fig. 5.

Sequential effects of proteasome inhibitors in the overloaded heart. Proteasome activity, NF-κB activity, collagen type I transcript, LV-to-tibial length ratio, and ejection fraction in banded mice treated with vehicle or epoxomicin for 1 day, starting 2 wk after banding, and analyzed 24 h later. #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding vehicle; *P < 0.05 vs. sham (Top and bottom: n = 4/group).

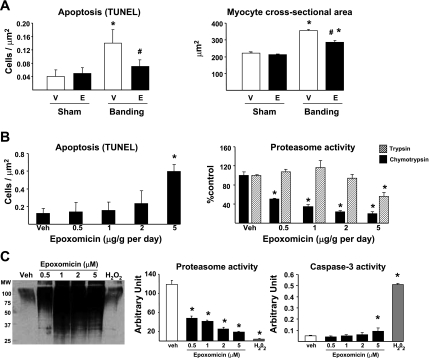

The effects of epoxomicin are independent from apoptosis.

Proteasome inhibitors are now used in the treatment of certain forms of cancer for their cytotoxic and proapoptotic effect (31). The decreased heart mass observed after epoxomicin treatment could be due to myocyte apoptosis. Therefore, we tested whether epoxomicin would induce apoptosis in the heart. Myocyte apoptosis was measured by TUNEL in hearts from mice submitted to 3 wk aortic banding with or without epoxomicin. When compared with that in sham-operated animals, apoptosis increased by about fourfold in hearts after 3 wk banding in the presence of the vehicle, which was reduced by half in the group treated with epoxomicin for 1 wk (Fig. 6A). To further confirm that epoxomicin treatment after aortic banding reduces cardiac cell size, myocyte cross-sectional area was measured in the four experimental groups. A significant increase in cross-sectional area was observed after 3 wk banding in vehicle-treated mice, which was significantly reduced by 50% upon epoxomicin treatment (Fig. 6A). Therefore, the reduction in LV/TL upon epoxomicin treatment in banded hearts corresponds to reduced cardiac cell size and not to increased apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

Epoxomicin does not affect myocyte apoptosis. A: measurement of apoptosis by transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) and cardiac cell size by myocyte cross-sectional area in sham-operated animals vs. 3-wk banded mice treated with vehicle or epoxomicin during the last week. #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding vehicle; *P < 0.05 vs. sham (n = 5/group). B: daily treatment of sham-operated mice with vehicle (Veh) or escalating doses of epoxomicin for 1 wk followed by the measurement of apoptosis by TUNEL and chymotryptic-like and tryptic-like proteasome activities. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (n = 3/group). C: treatment of isolated cardiac myocytes with vehicle, different concentrations of epoxomicin, or with 100 μM H2O2 for 24 h and measurement of polyubiquitylation, proteasome activity, and myocyte apoptosis by caspase-3 activity. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle (n = 3/group).

To further address the potential toxicity of epoxomicin in the heart in vivo, sham-operated mice were treated daily for 1 wk with different doses of epoxomicin, ranging from 0.5 to 5.0 mg/kg. At the end of the protocol, myocyte apoptosis was measured by TUNEL. Epoxomicin treatment significantly increased the number of TUNEL-positive myocytes at the highest dose tested, i.e., 5.0 mg/kg, but not at the dose (0.5 mg/kg) used in our study (Fig. 6B). Proteasome activity was measured in these different groups. Epoxomicin binds the β5-subunit of the 20S core particle and therefore inhibits only the chymotryptic activity of the proteasome (40). At the dose used in our study (0.5 mg/kg), that activity was decreased by about 50%, whereas a maximal 80% inhibition was observed at higher doses (Fig. 6B). Epoxomicin did not affect the tryptic activity of the proteasome, except at the dose of 5.0 mg/kg (Fig. 6B). Therefore, the increased apoptosis observed at 5.0 mg/kg may result from a toxic, rather than a pharmacological, effect when the drug concentration is too high to remain specific for the chymotryptic activity of the proteasome.

The relative toxicity of epoxomicin compared with well-known proapoptotic agents was further investigated in vitro, using isolated rat cardiac myocytes. We showed before that, in such models, myocyte growth stimulated by prohypertrophic agonists can be prevented by proteasome inhibition with epoxomicin or lactacystin (23). Isolated cardiac myocytes were cultured and treated with different concentrations of epoxomicin for 24 h, after which proteasome activity, protein polyubiquitylation, and apoptosis were measured. The addition of epoxomicin reduced the chymotryptic activity of the proteasome by up to 90% in myocytes (Fig. 6C). The efficiency of proteasome inhibition was further demonstrated by the accumulation of polyubiquitylated proteins (Fig. 6C). Caspase-3 activation showed a significant increase compared with vehicle-treated myocytes at only the highest (5 μM) concentration of the drug (Fig. 6C). However, the addition of 100 μM H2O2 to the myocyte preparation, used as a positive control, increased apoptosis to a much larger extent than did epoxomicin (Fig. 6C). The loss of proteasome activity in the H2O2 group probably reflects the increased death rate of the myocytes rather than a true inhibition of the proteasome, because this group does not show an accumulation of polyubiquitylated proteins (Fig. 6C). These data, taken together with the data obtained in vivo (Fig. 6B), confirm that the proteasome can be significantly inhibited without necessarily inducing apoptosis in myocytes.

DISCUSSION

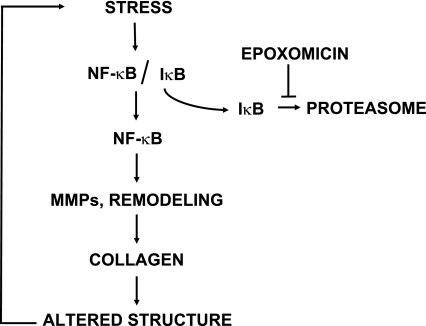

The main finding of our study is the observation that treatment of the overloaded heart with proteasome inhibitors started after the onset of hypertrophy leads to a stabilization of contractile parameters, a regression of preexisting hypertrophy, a decrease in LW/TL, and a decrease in the accumulation of interstitial collagen. Therefore, proteasome inhibition can reduce preexisting hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling. The proposed mechanism that is discussed below is summarized in Fig. 7. Epoxomicin is considered one of the most specific inhibitors of the proteasome (40). Not only does it target only the chymotryptic activity of the proteasome (30), but it is also devoid of any inhibitory effect on proteasome-independent chymotryptic enzymes (23). In addition, the effects of epoxomicin in the heart can be reproduced by lactacystin (13, 23), a proteasome inhibitor with lower specificity and displaying a totally different chemical structure than epoxomicin (9, 28, 40).

Fig. 7.

Proposed mechanism for the action of proteasome inhibitors in the overloaded heart. Upon stress, in this case pressure overload, the transcription factor NF-κB is activated upon removal of its inhibitory subunit IκB, which is degraded by the proteasome. NF-κB activation stimulates the expression of collagen isoforms, which leads to cardiac remodeling, further alteration in cardiac structure, and increased stress. Inhibition of the proteasome by epoxomicin prevents IκBα degradation, thereby restraining NF-κB activity, which prevents the increase in expression of collagen.

It is usually considered that cardiac hypertrophy represents an adaptive response to pressure overload that progressively evolves into a maladaptive condition due to increased wall stress, Ca2+ overload, increased energetic demand, and apoptosis among other factors (5). In that context, it may seem counterintuitive to prevent or reduce hypertrophy in the face of overload. However, several recent studies support that concept. In one example, increased wall stress upon banding in mice with genetic deletions preventing the development of hypertrophy was not accompanied by a functional deterioration of the heart, at the opposite of the corresponding wild-type mice (15). In addition, treatment with rapamycin, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin, before the induction of pressure overload, decreases significantly the development of hypertrophy without impairing contractile function (47), whereas treatment with rapamycin after induction of overload leads to a regression of hypertrophy and to a stabilization of contractility (36). Our previous data demonstrated that epoxomicin prevents hypertrophy when administered before the onset of pressure overload (13), and the present study shows that it also reverses preexisting hypertrophy in the overloaded heart and stabilizes contractile function. Whether cardiac function may be actually improved by epoxomicin would require a longer duration of treatment. It may seem counterintuitive that blocking a pathway of proteolysis will reduce rather than increase cardiac mass. This paradox may be explained by the fact that proteasome inhibition blocks an inducible mechanism of cell growth activated by NF-κB in conditions of cardiac stress (Fig. 7). In addition, one of our previous studies suggests that proteasome inhibition is accompanied by a blockage of translation initiation to reach a new steady state between protein synthesis and degradation (23). Whether such observation can be extended beyond a rodent model needs to be studied in future investigations. In addition, proteasome inhibition can reverse stable, chronic cardiac hypertrophy in absence of overload, also without affecting cardiac contractility (23), and it decreases chronic isoproterenol-induced hypertrophy, although cardiac function and proteasome activity were not measured in that case (50).

A major component of the ventricular remodeling following pressure overload is the accumulation of extracellular matrix and, in particular, of collagen. The accumulation of collagen in the failing heart affects cardiac geometry and wall stress and thereby alters myocyte function and size (25). Our experiments show that collagen accumulation in the overloaded heart can be blunted by proteasome inhibitors, most likely through a downregulation of NF-κB activity. In the normal heart, NF-κB activity is prevented by its specific inhibitor, IκBα (22), which is constitutively produced and which binds NF-κB, thereby preventing the activation of the transcription factor. Multiple pathways mediating the cellular stress triggered by pressure or volume overload can activate IκBα kinases, which phosphorylate IκBα (21). Upon phosphorylation, IκBα is tagged for ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation, thereby freeing NF-κB, which becomes transcriptionally active (21). Although NF-κB is not sufficient in itself to activate collagen transcription (38), it can do so indirectly through increased expression of MMPs and in particular of the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 (38). Among the multiple forms of MMPs, the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 are expressed both in cardiac fibroblasts and in myocytes and can degrade several types of collagen (including the types I and III) (48). It could be argued that, because the function of MMPs is to degrade collagen, the prevention of MMP expression by proteasome inhibitors should rather increase collagen density in myocardial tissue. However, the dissociation of collagen bundles by MMPs automatically leads to additional collagen synthesis through transcriptional activation of the corresponding genes (26). This conclusion is supported by observations in genetically modified mouse models. The deletion of MMP-9 decreases ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction by limiting collagen accumulation, whereas the deletion of MMP-2 produces a similar effect in a model of pressure overload (14, 34). Taken these data together, we propose that a repression of NF-κB activation upon pressure overload by proteasome inhibitors blocks the transcriptional activation of MMPs, thereby preventing the transcription of genes encoding collagen isoforms (Fig. 7). Our observations support a central role for NF-κB repression upon treatment with proteasome inhibitors because short-term treatment with epoxomicin led to a decreased activity of NF-κB before any change in heart mass, ventricular function, or ventricular remodeling could be detected.

Epoxomicin treatment did not induce cardiac toxicity, as assessed by the improvement of cardiac contractile function and the absence of apoptosis. The acute toxicity of proteasome inhibitors is the subject of intense debate, especially because of the proapoptotic and therapeutic effect of the proteasome inhibitor PS341 or Bortezomib (Velcade) in cancer (1). Bortezomib is particularly useful in the treatment of hematological malignancies, such as myeloma, macroglobulinemia, and lymphoma (31). The therapeutic effect of Bortezomib is also related to an inhibition of NF-κB, particularly in myeloma, a tumor in which this transcription factor controls the expression of interleukin-6, which is critical for cell growth and adhesion, as well as angiogenesis (2). Velcade is particularly efficient in cancers from secretory cells. These cells rely heavily on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for protein synthesis and secretion, but this high rate of translation automatically includes a large proportion of misfolded and denatured proteins that must be destroyed. An accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER results in the translocation of nascent denatured peptidic chains from the ER back to the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a process known as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (33). In the presence of proteasome inhibitors, ERAD is blocked, leading to a rapid accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, which triggers the “unfolded protein response,” resulting in the death of the tumor cell by apoptosis (31, 53).

These observations in myeloma raise the question as to why epoxomicin is not more toxic for normal cells, including cardiac myocytes. It is possible that different effects result from proteasome inhibition depending on the cell type that is targeted. For example, proteasome inhibition promotes cell survival in neurons (52) or endothelial cells (49). The proteasome cleaves the client protein through at least three different proteases, including a trypsin-like (cutting the peptidyl bond involving basic amino acids), a chymotrypsin-like (for hydrophobic amino acids), and a caspase-like or peptidylglutamyl hydrolase (acid amino acids) (22). Epoxomicin is highly specific for the chymotryptic activity (30) and therefore does not totally inhibit the proteasome. It is estimated that epoxomicin can block the proteolytic activity of the proteasome by no more than 30–40% (30), which may explain why proteasome inhibitors have limited toxicity for normal cells with low secretory function. In a dose-response experiment, we measured whether 1 wk daily treatment with epoxomicin would increase myocyte apoptosis; however, no difference was observed between the dose used in our study and the vehicle. Although the measurement of apoptosis by TUNEL shows only what happens in the heart at one specific time point, high doses of epoxomicin induced apoptosis after 1 wk, and the comparison of the chymotryptic and tryptic activities in these samples supports that such proapoptotic effect results from a toxic effect of the molecule rather than from a pharmacological consequence of proteasome inhibition.

In conclusion, proteasome inhibition after the onset of pressure overload prevents further deterioration of cardiac function, reduces cardiac cell size, and limits ventricular remodeling. These effects of proteasome inhibitors seem largely due to an inhibition of the NF-κB pathway mediating an accumulation of interstitial collagen and further cardiac remodeling. These results support a potential therapeutic role for proteasome inhibition in the treatment of cardiac hypertrophy.

GRANTS

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL-033107, HL-059139, HL-069752, AG-014121, and AG-027211 (to S. F. Vatnar) and HL-072863 (to C. Depre) and American Heart Association Grant 0640011N (to C. Depre).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J Proteasome inhibition in cancer: development of PS-341. Semin Oncol 28: 613–619, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson K, Lust J. Role of cytokines in multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol 36: 14–20, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell B, Adams J, Shin Y, Lefer A. Cardioprotective effects of a novel proteasome inhibitor following ischemia and reperfusion in the isolated perfused rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 31: 467–476, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Madura K. Increased proteasome activity, ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and eEF1A translation factor detected in breast cancer tissue. Cancer Res 65: 5599–5606, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chien K Stress pathways and heart failure. Cell 98: 555–558, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162: 156–159, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohn JN Structural basis for heart failure. Ventricular remodeling and its pharmacological inhibition. Circulation 91: 2504–2507, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costelli P, Garcia-Martinez C, Llovera M, Carbo N, Lopez-Soriano F, Agell N, Tessitore L, Baccino F, Argiles J. Muscle protein waste in tumor-bearing rats is effectively antagonized by a beta 2-adrenergic agonist (clenbuterol). Role of ATP-ubiqitin-dependent proteolytic pathway. J Clin Invest 95: 2367–2372, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craiu A, Gaczynska M, Akopian T, Gramm CF, Fenteany G, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. Lactacystin and clasto-lactacystin beta-lactone modify multiple proteasome beta-subunits and inhibit intracellular protein degradation and major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation. J Biol Chem 272: 13437–13445, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depre C, Hase M, Gaussin V, Zajac A, Wang L, Hittinger L, Ghaleh B, Yu X, Kudej RK, Wagner T, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. H11 kinase is a novel mediator of myocardial hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res 91: 1007–1014, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Depre C, Kim SJ, John AS, Huang Y, Rimoldi OE, Pepper JR, Dreyfus GD, Gaussin V, Pennell DJ, Vatner DE, Camici PG, Vatner SF. Program of cell survival underlying human and experimental hibernating myocardium. Circ Res 95: 433–440, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depre C, Shipley G, Chen W, Han Q, Doenst T, Moore M, Stepkowski S, Davies P, Taegtmeyer H. Unloaded heart in vivo replicates fetal gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 4: 1269–1275, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depre C, Wang Q, Yan L, Hedhli N, Peter P, Chen L, Hong C, Hittinger L, Ghaleh B, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Madura K. Activation of the cardiac proteasome during pressure overload promotes ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 114: 1821–1828, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ducharme A, Frantz S, Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Lindsey M, Rohde LE, Schoen FJ, Kelly RA, Werb Z, Libby P, Lee RT. Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 attenuates left ventricular enlargement and collagen accumulation after experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 106: 55–62, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esposito G, Rapacciuolo A, Naga Prasad SV, Takaoka H, Thomas SA, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Genetic alterations that inhibit in vivo pressure-overload hypertrophy prevent cardiac dysfunction despite increased wall stress. Circulation 105: 85–92, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eto M, Kouroedov A, Cosentino F, Luscher TF. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 mediates endothelial cell activation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circulation 112: 1316–1322, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frantz S, Hu K, Bayer B, Gerondakis S, Strotmann J, Adamek A, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Absence of NF-κB subunit p50 improves heart failure after myocardial infarction. FASEB J 20: 1918–1920, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geng Y, Ishikawa Y, Vatner D, Wagner T, Bishop S, Vatner S, Homcy C. Apoptosis of cardiac myocytes in Gsα transgenic mice. Circ Res 84: 34–42, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson UE, Heid CA, Williams PM. A novel method for real time quantitative RT-PCR. Genome Res 6: 995–1001, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hase M, Depre C, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. H11 has dose-dependent and dual hypertrophic and proapoptotic functions in cardiac myocytes. Biochem J 388: 475–483, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev 18: 2195–2224, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedhli N, Pelat M, Depre C. Protein turnover in cardiac cell growth and survival. Cardiovasc Res 68: 186–196, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedhli N, Wang L, Wang Q, Rashed E, Tian Y, Sui X, Madura K, Depre C. Proteasome activation during cardiac hypertrophy by the chaperone H11 Kinase/Hsp22. Cardiovasc Res 77: 497–505, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirotani S, Otsu K, Nishida K, Higuchi Y, Morita T, Nakayama H, Yamaguchi O, Mano T, Matsumura Y, Ueno H, Tada M, Hori M. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappaB and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in G-protein-coupled receptor agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circulation 105: 509–515, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iimoto D, Covell J, Harper E. Increase in cross-linking of type 1 and type 3 collagens associated with volume overload hypertrophy. Circ Res 63: 399–408, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janicki J, Brower G, Gardner J, Chancey A, Stewart J. The dynamic interaction between matrix metalloproteinase activity and adverse myocardial remodeling. Heart Fail Rev 9: 33–42, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junqueira LC, Bignolas G, Brentani RR. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem J 11: 447–455, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler B, Tortorella D, Altun M, Kisselev A, Fiebiger E, Hekking B, Ploegh H, Overkleeft H. Extended peptide-based inhibitors efficiently target the proteasome and reveal overlapping specificities of the catalytic beta-subunits. Chem Biol 8: 913–929, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kisselev A, Goldberg A. Monitoring activity and inhibition of 26S proteasomes with fluorogenic peptide substrates. Methods Enzymol 398: 364–378, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kisselev AF, Callard A, Goldberg AL. Importance of the different proteolytic sites of the proteasome and the efficacy of inhibitors varies with the protein substrate. J Biol Chem 281: 8582–8590, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H, Iwakoshi N, Anderson K, Glimcher L. Proteasome inhibitors disrupt the unfolded protein response in myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9946–9951, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luss H, Schmitz W, Neumann J. A proteasome inhibitor confers cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 54: 140–151, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marciniak S, Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev 86: 1133–1149, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsusaka H, Ide T, Matsushima S, Ikeuchi M, Kubota T, Sunagawa K, Kinugawa S, Tsutsui H. Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase 2 ameliorates myocardial remodeling in mice with chronic pressure overload. Hypertension 47: 711–717, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maytin M, Colucci WS. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. J Nucl Cardiol 9: 319–327, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMullen J, Sherwood M, Tarnavski O, Zhang L, Dorfman A, Shioi T, Izumo S. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin regresses established cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. Circulation 109: 3050–3055, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meiners S, Dreger H, Fechner M, Bieler S, Rother W, Gunther C, Baumann G, Stangl V, Stangl K. Suppression of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Hypertension 51: 302–308, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meiners S, Hocher B, Weller A, Laule M, Stangl V, Guenther C, Godes M, Mrozikiewicz A, Baumann G, Stangl K. Downregulation of matrix metalloproteinases and collagens and suppression of cardiac fibrosis by inhibition of the proteasome. Hypertension 44: 471–477, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitch W, Goldberg A. Mechanisms of muscle wasting. N Engl J Med 335: 1897–1905, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powell SR The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac physiology and pathology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1–H19, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell SR, Davis KJ, Divald A. Optimal determination of heart tissue 26S-proteasome activity requires maximal stimulating ATP concentrations. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42: 265–269, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purcell N, Tang G, Yu C, Mercurio F, DiDonato J, Lin A. Activation of NF-kappa-B is required for hypertrophic growth of primary art neonatal ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6668–6673, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pye J, Ardeshirpour F, McCain A, Bellinger DA, Merricks E, Adams J, Elliott PJ, Pien C, Fischer TH, Baldwin AS Jr, Nichols TC. Proteasome inhibition ablates activation of NF-κB in myocardial reperfusion and reduces reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H919–H926, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiu H, Tian B, Resuello R, Natividad F, Peppas A, Shen Y, Vatner D, Vatner S, Depre C. Sex-specific regulation of gene expression in the aging monkey aorta. Physiol Genomics 29: 169–180, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rivett A Proteasomes: multicatalytic proteinase complexes. Biochem J 291: 1–10, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roff M, Thompson JF, Rodriguez M, Jacque J, Baleux F, Arenza-Seisdos F, Hay R. Role of IkBa ubiquitination in signal-induced activation of NF-kB in vivo. J Biol Chem 271: 7844–7850, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shioi T, McMullen JR, Tarnavski O, Converso K, Sherwood MC, Manning WJ, Izumo S. Rapamycin attenuates load-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circulation 107: 1664–1670, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spinale F, Coker M, Bond B, Zellner J. Myocardial matrix degradation and metalloproteinase activation in the failing heart. Cardiovasc Res 46: 225–238, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stangl V, Lorenz M, Meiners S, Ludwig A, Bartsch C, Moobed M, Vietzke A, Kinkel H, Baumann G, Stangl K. Long-term up-regulation of eNOS and improvement of endothelial function by inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. FASEB J 18: 272–279, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stansfield WE, Tang RH, Moss NC, Baldwin AS, Willis MS, Selzman CH. Proteasome inhibition promotes regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H645–H650, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tawa N, Odessey R, Goldberg A. Inhibitors of the proteasome reduce the accelerated proteolysis in atrophying rat skeletal muscles. J Clin Invest 100: 197–203, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Leyden K, Siddiq A, Ratan R, Lo E. Proteasome inhibition protects HT22 neuronal cells from oxidative glutamate toxicity. J Neurochem 92: 824–830, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest 115: 2656–2664, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]