Abstract

Cyclical changes in production of neuroactive steroids during the oestrous cycle induce significant changes in GABAA receptor expression in female rats. In the periaqueductal grey (PAG) matter, upregulation of α4β1δ GABAA receptors occurs as progesterone levels fall during late dioestrus (LD) or during withdrawal from an exogenous progesterone dosing regime. The new receptors are likely to be extrasynaptically located on the GABAergic interneurone population and to mediate tonic currents. Electrophysiological studies showed that when α4β1δ GABAA receptor expression was increased, the excitability of the output neurones in the PAG increased, due to a decrease in the level of ongoing inhibitory tone from the GABAergic interneurones. The functional consequences in terms of nociceptive processing were investigated in conscious rats. Baseline tail flick latencies were similar in all rats. However, acute exposure to mild vibration stress evoked hyperalgesia in rats in LD and after progesterone withdrawal, in line with the upregulation of α4β1δ GABAA receptor expression.

1. Introduction

The periaqueductal (PAG) grey matter is involved in regulating a remarkable number of bodily functions. Circuits controlling nociception, temperature regulation, micturition, vocalisation, cardiorespiratory function, and sexual behaviours are all dependent on the functional integrity of this midbrain region [1–5]. The PAG is also involved in producing emotional changes, particularly those associated with fear and defensive behaviour [6, 7], and has the ability to modulate activity in its various control circuits to orchestrate changes in the behavioural response pattern that are appropriate to an ever-changing environment [8]. In females, the PAG operates within a constantly changing hormonal milieu that results from the cyclical changes in production of neuroactive gonadal steroids during the menstrual cycle (oestrous cycle in animals). The lipophilic nature of these molecules means that they readily gain access to the brain from the circulation [9]. Here we review the results of our recent investigations into the functional consequences of changes in circulating levels of progesterone during the oestrous cycle in female rats. These experimental studies have revealed remarkable hormone-linked changes in the intrinsic excitability of the PAG circuitry that are reflected by significant changes in the behaviour of the animal.

2. Cyclical Changes in Progesterone Secretion in Females

In women, production of progesterone undergoes substantial changes during the menstrual cycle. Plasma levels of the steroid remain at a constant low level during the first half of the cycle. Following ovulation, secretion of progesterone by the corpus luteum increases, resulting in elevated blood plasma levels [10]. In the absence of a fertilised ovum the corpus luteum then degenerates, with an associated rapid fall in plasma progesterone production prior to menstruation.

It has long been recognised that the cyclical production of gonadal hormones during the menstrual cycle can trigger significant changes in psychological status. In up to 75% of women, the late luteal phase of the cycle, when progesterone levels decline rapidly, is associated with the development of adverse psychological symptoms; these may include irritability, mood swings, aggression, and anxiety [11]. Additionally, bodily changes such as breast tenderness and bloating may occur and responsiveness to painful stimuli becomes enhanced [12, 13]. Importantly, symptoms fail to develop in women during anovulatory cycles [14] indicating a causal relationship between changes in gonadal steroid levels and brain function. The oestrous cycle of rodents acts as a suitable model of the human menstrual cycle, and offers the opportunity to study hormone-induced plasticity of brain function within intact circuits and to relate this to a behavioural outcome. The late dioestrus (LD) phase in rats, when progesterone levels are falling naturally, correlates with the premenstrual phase in women and increased anxiety and aggression have been reported to develop during dioestrus in rats [15–17]. In rats progesterone levels also fall rapidly during proestrus following the preovulatory surge [18]. However, the dynamics of this short-lasting surge in progesterone production are not sufficient to trigger the long-lasting changes in GABAergic function that accompany LD (see below, also [19] for discussion of this point).

3. Neural Actions of the Progesterone Metabolite Allopregnanolone

Within the brain, progesterone produces genomic effects via neuronal nuclear-bound receptors. In addition, it can also act at the cell membrane level. These nongenomic effects are mediated not by progesterone itself but via the actions of its neuroactive metabolite 3 alpha-hydroxy-5 alpha-pregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone, ALLO). ALLO is a steroidal compound that is synthesized de novo within the brain from progesterone via the actions of 5α-reductase and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (for review, see [20]). ALLO acts at two sites on the GABAA receptor. The first is an activation site that produces direct receptor activation and the second is a potentiation site at which ALLO acts as a powerful positive allosteric modulator to enhance the effects of GABA [21]. Potentiation occurs in response to low nanomolar concentrations of ALLO [22] whereas higher, micromolar concentrations, as seen for example at parturition [23], are required for direct activation of GABAA receptors [24]. The levels of ALLO present in the brain are influenced by the circulating levels of progesterone and we have shown recently that ALLO from the plasma gains ready access to the PAG where it produced a decrease in neuronal excitability via a GABAA-mediated mechanism [25]. In other brain structures, changes in the concentration of ALLO following fluctuations in the level of circulating progesterone have been shown to trigger upregulation of GABAA receptor subunit expression that leads to changes in neural excitability and behaviour [26].

4. Progesterone Withdrawal-Induced Plasticity of GABA Receptor Function in the PAG

GABAA receptors are pentameric structures that surround a single chloride channel. Although most receptors are comprised of only 3 subunit types, the large pool of available subunits means that receptors can be comprised of many different subunit combinations [27]. The functional characteristics of individual receptor subtypes are determined by their subunit composition. There are several indications that fluctuations in the concentrations of progesterone play a major role in determining the temporal pattern of expression of certain subunits of the GABAA receptor. For example, withdrawal of cultured cerebellar granule cells or cortical neurones from long-term treatment with progesterone was accompanied by upregulation of α4 subunit mRNA [28, 29]. Similarly, hippocampal tissue from progesterone-withdrawn rats showed upregulation of both α4 and δ subunit mRNA [26, 30]. These effects were mediated not by progesterone itself but by its neuroactive metabolite ALLO and presumably represent a response of the neurone in an effort to maintain homeostasis. Thus progesterone influences neural function directly via a genomic action at the nuclear progesterone receptor and indirectly via a nongenomic action of ALLO at the membrane-bound GABAA receptor.

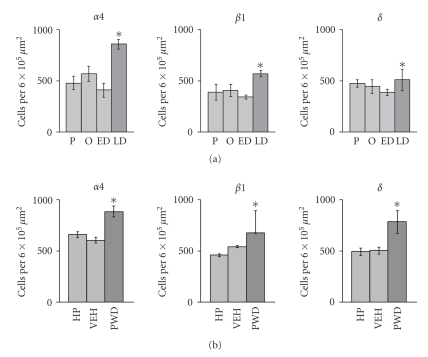

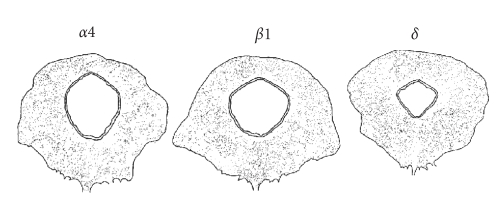

The PAG is another brain region that shows a susceptibility to phasic changes in the ambient level of progesterone and hence ALLO. Using immunohistochemistry, we found that 24-hour withdrawal of female rats from long-term dosing with exogenous progesterone (5 mg Kg−1 IP twice daily for 6 days) leads to upregulation of α4, β1, and δ GABAA receptor subunit protein in neurones in the PAG (Figure 1) [31]. Within the PAG, subunit-immunoreactive neurones were distributed throughout all subdivisions (Figure 2). However, upregulation after progesterone withdrawal was most marked in the dorsolateral column [32] where the density of GABAergic neurones, in which most α4β1δ receptors are expressed [31], was the greatest [33].

Figure 1.

Density of α4, β1, and δ GABAA receptor subunit-immunoreactive neurones in the PAG in (a) spontaneously cycling female rats and (b) rats that had undergone a progesterone withdrawal regime. Abbreviations: P: proestrus; O: oestrus; ED: early dioestrus; LD: late dioestrus; HP: high progesterone; VEH: vehicle treated; PWD: progesterone-withdrawn. n = 5 for each group, all values mean ± SEM. *P < .05, post hoc Fischer test after significant (P < .05) one-way ANOVA. Data redrawn from [31, 32].

Figure 2.

Camera lucida reconstruction showing distribution of α4, β1, and δ GABAA receptor subunit positive neurons in representative sections taken from the mid PAG level from a rat in early dioestrus. The figure is adapted from [31].

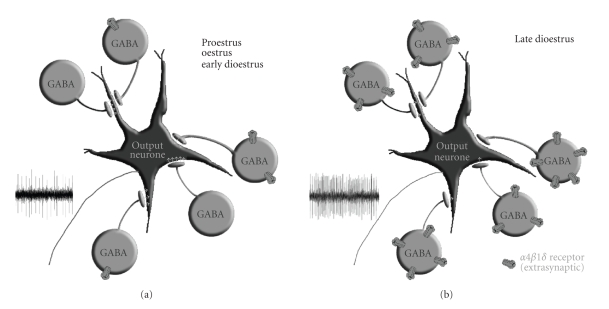

We have been able to translate the findings obtained using an exogenous dosing regime to the natural fluctuations in the hormone that occur during the oestrous cycle. During LD, when plasma levels of progesterone are falling, a parallel upregulation of α4, β1, and δ GABAA receptor subunit protein occurred within the PAG [34]. This suggests that new GABAA receptors with the α4β1δ subunit configuration had been formed in response to the falling steroid levels in the brain. GABAA receptors containing δ subunits are likely to be extrasynaptically located [35] and those with the α4β1δ configuration are characterised by an extremely low EC50 for GABA [36]. The α4β1δ GABAA receptors in the PAG should therefore be activated by the level of GABA present in the extracellular fluid and be responsible for mediating tonic currents [35, 36]. Expression of α4, β1, and δ subunit protein was confined predominantly to the GABAergic neuronal population in the PAG [32]. These two factors, that is, sensitivity to GABA and cellular location, may provide an important key to the functional consequences of progesterone withdrawal-induced receptor plasticity. In functional terms, increased expression of α4β1δ receptors on GABAergic neurones would be expected to lead to a reduction in the level of their activity, thus disinhibiting the output neurones within the PAG by reducing the level of ongoing GABAergic tone (Figure 3). Hence, one would expect to see an increase in the excitability of the various neural control systems located within the PAG. The PAG is organised functionally in terms of a number of longitudinal columns that integrate and control diverse aspects of its function [37]. The oestrous cycle-linked upregulation of α4, β1, and δ GABAA receptor subunit protein was seen in all regions of the PAG with little evidence of somatotopic localisation. Hence, the functional consequences of receptor plasticity are likely to be widespread and not confined to any one aspect of PAG function.

Figure 3.

Cartoon to depict changes in GABAA receptor expression in the PAG at different stages of the oestrous cycle. α4β1δ GABAA receptors are expressed mainly by GABAergic interneurones where they are extrasynaptically located and mediate tonic currents. The excitability of output neurons from the PAG is limited by spontaneous activity in GABAergic interneurones. (a) When expression of α4β1δ GABAA receptors is low during proestrus (Pro), oestrus (O), and early dioestrus (ED), high levels of activity in the interneurone population limit the excitability of the output neurons. (b) When progesterone levels fall during late dioestrus (LD), increased expression of α4β1δ receptors leads to an increase in tonic current carried by GABAergic cells, thus limiting their on-going activity. The output neurones therefore become intrinsically more excitable, and their threshold for activation is lowered. The figure is adapted from [38].

5. Oestrous Cycle-Linked Changes in Neural Excitability of the Female PAG

The excitability of the neural circuits of the PAG is normally regulated by tonic activity of GABAergic neurones. At the neuronal level, the presence of ongoing GABAergic inhibition within the PAG was revealed by the increase in firing rate of output neurones in the presence of a GABAA antagonist [19]. In the conscious rat, the functional importance of the tonically active GABAergic control system is manifested by the dramatic behavioural changes elicited by microinjection of GABAA antagonists into this region [39–42]. To date, most of these studies have been restricted to male animals. However, given the plasticity of the GABAergic control system in the PAG in females, changes in the functional excitability of the neural circuitry might be expected to occur at different stages of the oestrous cycle. Indeed, our electrophysiological studies have shown that GABA tone in the PAG in females is reduced during LD [19] and also in oestrus, although the latter effect is unlikely to be related to plasticity of α4β1δ receptor expression (for a discussion on this point see [19]). Changes in the intrinsic level of GABAergic tone in the PAG have the potential to impact significantly on the wide range of the behaviours that are controlled by this region. Indeed, even in the anaesthetised preparation, we were able to show changes in responsiveness of single neurones in the PAG to the panicogenic and pronociceptive CCK2 receptor agonist pentagastrin at different stages of the cycle [19].

6. Behavioural Consequences of Steroid Hormone Withdrawal-Evoked Changes in PAG Function

The PAG is a source of multiple descending control pathways to the spinal cord that exert both inhibitory and facilitatory influences on the spinal processing of nociceptive information [43]. Both pro- and antinociceptive control systems are thought to be tonically active under normal conditions but the balance between them is in a state of constant dynamic flux [44, 45]. We have recently begun to investigate the behavioural consequences of steroid hormone-evoked changes in the excitability of the circuitry in the conscious animal, focussing on changes in responsiveness to painful stimuli as well as on indices of anxiety.

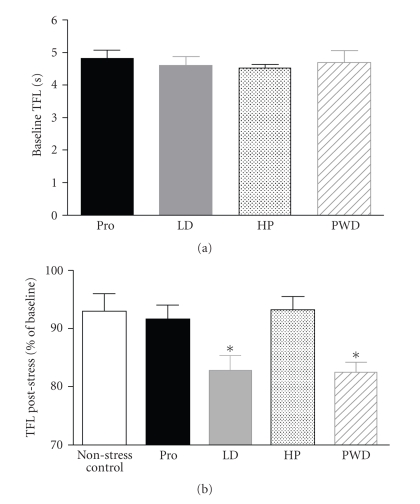

The tail flick latency (TFL) in response to radiant heat applied to the underside of the tail elicits a withdrawal reflex that is a commonly used index of sensitivity to acute cutaneous pain in conscious rats [46]. We compared TFLs in rats that had undergone a progesterone withdrawal regime (5 mg Kg−1 IP twice daily for 6 days followed by 24-hour withdrawal) with those obtained from rats in proestrus (Pro) and LD. These two stages of the oestrous cycle were chosen as being representative of low and high expressions of α4β1δ GABAA receptors in the PAG (see Figure 1). Since changing hormone levels might also induce changes in stress or anxiety levels in rats used for nociception testing, which could potentially influence their perception of pain [46], we also observed the behaviour of animals in a 1 m × 1 m open field arena to assess intrinsic anxiety levels [47].

Experiments involving nociceptive testing were carried out under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and conformed with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication no. 85–23, revised 1985). Female Wistar rats were habituated to a restraining tube. TFLs were measured at 5-minute intervals over a 15-minute period, that is 3 tail flick tests, to obtain a basal value for TFL. There was no difference in basal TFLs between any of the different groups of spontaneously cycling rats or the progesterone-treated animals (Figure 4(a)). Similarly, there was no difference in any of the behavioural indices measured in the open field (Table 1). We next investigated interactions between anxiety and nociception. The rats were subjected to mild nonnoxious stress by vibrating the restraining tube with the rat inside it for 5 minutes at 4 Hz [48]. During the vibration stress, the rats showed signs of anxiety that included micturition, defaecation, and vocalisation. Immediately following the vibration stress, tail flick testing was resumed. Rats that were undergoing progesterone-withdrawal had developed a poststress hyperalgesia that was manifested as a significant decrease in tail flick latency that persisted for 10 minutes (Figure 4(b)). Rats maintained on the progesterone dosing schedule failed to develop hyperalgesia (Figure 4(b)). Spontaneously cycling rats in Pro (low α4β1δ GABAA receptor expression in the PAG) were compared with rats in LD (high α4β1δ GABAA receptor expression in the PAG) using the same protocol. Rats in LD displayed a significant hyperalgesia following the vibration stress, whereas rats in Pro showed no change in TFL (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4.

(a) Baseline tail flick latency in spontaneously cycling female Wistar rats in proestrus (Pro) and late dioestrus (LD) and in rats undergoing progesterone treatment (HP) or withdrawal from an exogenous progesterone dosing regime (PWD). Data show mean values of three readings taken at 5-minute intervals. All values mean ± SEM. Pro: n = 13, LD: n = 12, HP: n = 8, PWD: n = 7. (b) Change in tail flick latency (TFL) following 5-minute exposure to nonnoxious vibration stress in normally cycling and progesterone-withdrawn female Wistar rats. Data represent mean values obtained during 10 minutes immediately poststress as a percentage of the mean baseline level measured during 10 minutes prior to the stress. A control group comprising rats in proestrus and late dieostrus received no vibration stress. All values mean ± SEM; no stress (control): n = 12, Pro: n = 13, LD: n = 12, HP: n = 8, PWD: n = 7. *P < .05, post hoc Dunnett’s test in comparison to control group after significant (P < .05) one-way ANOVA.

Table 1.

Behavioural indices in open field test for rats in proestrus, late dioestrus, and after progesterone withdrawal. All values mean ± SEM. Late dioestrus (LD, n = 15), proestrus (Pro, n = 22), high progesterone (HP, n = 7).

| Measure | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LD | Pro | HP | |

| Total distance travelled (cm) | 3827 ± 228 | 3737 ± 205 | 4328 ± 208 |

| Average speed (cm s−1) | 12.85 ± 0.76 | 12.91 ± 0.70 | 14.45 ± 0.70 |

| Time in central zone (%) | 2.56 ± 0.51 | 1.96 ± 0.25 | 2.82 ± 0.56 |

| Time in middle zone (%) | 10.00 ± 1.98 | 7.74 ± 1.42 | 6.75 ± 0.94 |

| Time in outer zone (%) | 86.60 ± 2.24 | 89.09 ± 1.73 | 90.85 ± 1.43 |

| Number of central zone re-entries | 4.25 ± 0.64 | 4.10 ± 0.62 | 3.57 ± 0.57 |

| Time rearing (%) | 18.53 ± 2.35 | 19.13 ± 2.01 | 14.13 ± 1.26 |

| Time freezing (%) | 0.30 ± 0.30 | 0.54 ± 0.44 | n/a |

| Time grooming (%) | 7.68 ± 1.51 | 6.48 ± 1.48 | 4.93 ± 1.38 |

These experiments failed to show any change in baseline thermal nociception in female Wistar rats at different stages of the oestrous cycle. In contrast, other investigators have been able to detect oestrous cycle-linked differences in sensitivity to pain [49–53]. However, the reports of differences in nociception with respect to cycle stage were equivocal. At best, it seems that cycle stage may influence responsiveness to pain in rats but only in some strains and under specific experimental conditions. In terms of PAG function, this suggests either that there is very little oestrous cycle-linked change in tonic descending control of spinal nociceptive processing or, alternatively, that the activity in the control systems is altered during the cycle but in such a way that there is little change in the net balance of control at the spinal cord level.

In line with the lack of oestrous cycle effect on basal pain sensitivity, we were also unable to detect any differences in basal anxiety levels using the open field test. This finding is supported by previous studies [54, 55] but not by the work of Frye et al. [56] who reported an increase in anxiety-related behaviour in a brightly lit open field during the dark phase of the day in rats in dioestrus. However, this study may not be directly comparable to the present work, since testing in bright light, as opposed to the relatively subdued lighting (60 lux) used in the present study, would be inherently more stressful to the rats [57] by compounding the anxiogenic effects of bright light and exposure to a novel environment.

Interestingly, in the present study oestrous cycle-related differences in responsiveness to pain became apparent in the setting of a mild stress that increased anxiety levels. Moreover, the oestrous cycle-linked hyperalgesia appeared only during LD, when α4β1δ receptor expression in the PAG would be upregulated. Rats undergoing withdrawal from progesterone, in which α4β1δ receptor expression in the PAG would also be upregulated, showed a hyperalgesia, indicating that the effect seen in the spontaneously cycling animals was likely to be hormone-linked. During the oestrous cycle, levels of a number of gonadal hormones change [18]. Oestradiol in particular has been shown to affect GABAergic function [58]. However, at the time when α4β1δ GABAA receptor expression increase during LD, plasma oestradiol levels are low and stable, suggesting that changes in progesterone rather than oestrogen are responsible for the changes in PAG function during LD. The results of our most recent work indicate that the PAG may be involved in mediating the oestrous cycle-linked hyperalgesia in the setting of mild anxiety. We have found that exposure to the vibration stress regime elicits differential expression of the immediate early gene c-fos in the ventrolateral PAG in rats in Pro and LD (Lovick and Devall, unpublished work). The ventrolateral PAG contains neurons that are a source of descending facilitation of spinal nociceptive inputs [59, 60]. Thus steroid hormone-linked changes in the excitability of descending control systems from the PAG may alter the level of descending control over spinal nociceptive processing and contribute to the hyperalgesia that develops in LD or during progesterone withdrawal.

Recent imaging studies in humans have also implicated the PAG in anxiety-induced hyperalgesia. Anticipatory anxiety in expectation of receiving a painful cutaneous thermal stimulus led not only to a heightened pain experience when the stimulus was delivered, that is hyperalgesia, but was also associated with activation of the PAG [61]. In women, increased responsiveness to noxious stimulation has been reported consistently during the luteal phase of menstrual cycle [12, 13]. In many women, anxiety levels are raised during the late luteal phase [11]. In any experimental scenario involving pain testing in human subjects, a degree of anxiety or apprehension is almost inevitable. Thus it is possible that the reported menstrual cycle-related differences in pain sensitivity in women may to a large extent be secondary to changes in anxiety levels rather than a primary response to changing hormone levels.

In female rats, falling progesterone levels can produce remarkable changes in the functional characteristics of neurones in the PAG, which may underlie certain oestrous cycle-linked changes in behaviour. These findings have implications for the design and interpretation of behavioural studies in female rodents in which the stage of the oestrous cycle may be a significant confounding influence. It is also possible that such hormone-linked changes may underlie the development of menstrual cycle-related disorders in susceptible women.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this article was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council, The Wellcome Trust, and the British Heart Foundation.

References

- 1.Matsumoto S, Levendusky MC, Longhurst PA, Levin RM, Millington WR. Activation of mu opioid receptors in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray inhibits reflex micturition in anesthetized rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;363(2):116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayward LF, Swartz CL, Davenport PW. Respiratory response to activation or disinhibition of the dorsal periaqueductal gray in rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;94(3):913–922. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00740.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sánchez C. Stress-induced vocalisation in adult animals. A valid model of anxiety? European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;463(1–3):133–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salzberg HC, Lonstein JS, Stern JM. GABAA receptor regulation of kyphotic nursing and female sexual behavior in the caudal ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of postpartum rats. Neuroscience. 2002;114(3):675–687. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guimarães APC, Prado WA. Pharmacological evidence for a periaqueductal gray-nucleus raphe magnus connection mediating the antinociception induced by microinjecting carbachol into the dorsal periaqueductal gray of rats. Brain Research. 1999;827(1-2):152–159. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker P, Carrive P. Role of ventrolateral periaqueductal gray neurons in the behavioral and cardiovascular responses to contextual conditioned fear and poststress recovery. Neuroscience. 2003;116(3):897–912. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carobrez AP, Teixeira KV, Graeff FG. Modulation of defensive behavior by periaqueductal gray NMDA/glycine-B receptor. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2001;25(7-8):697–709. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lovick TA, Bandler R. The organisation of the midbrain periaqueductal grey and the integration of pain behaviours. In: Hunt SP, Koltzenburg M, editors. The Neurobiology of Pain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul SM, Purdy RH. Neuroactive steroids. The FASEB Journal. 1992;6(6):2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLachlan RI, Robertson DM, Healy DL, Burger HG, de Kretser DM. Circulating immunoreactive inhibin levels during the normal human menstrual cycle. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1987;65(5):954–961. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-5-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner M. Premenstrual syndromes. Annual Review of Medicine. 1997;48:447–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fillingim RB, Ness TJ. Sex-related hormonal influences on pain and analgesic responses. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24(4):485–501. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley JL, III, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1999;81(3):225–235. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bäckström T, Andreen L, Birzniece V, et al. The role of hormones and hormonal treatments in premenstrual syndrome. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(5):325–342. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuluaga MJ, Agrati D, Pereira M, Uriarte N, Fernández-Guasti A, Ferreira A. Experimental anxiety in the black and white model in cycling, pregnant and lactating rats. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;84(2):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsson M, Ho H-P, Annerbrink K, Melchior LK, Hedner J, Eriksson E. Association between estrus cycle-related changes in respiration and estrus cycle-related aggression in outbred female Wistar rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(4):704–710. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcondes FK, Miguel KJ, Melo LL, Spadari-Bratfisch RC. Estrous cycle influences the response of female rats in the elevated plus-maze test. Physiology & Behavior. 2001;74(4-5):435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe G, Taya K, Sasamoto S. Dynamics of ovarian inhibin secretion during the oestrous cycle of the rat. Journal of Endocrinology. 1990;126(1):151–157. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1260151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brack KE, Lovick TA. Neuronal excitability in the periaqueductal grey matter during the estrous cycle in female Wistar rats. Neuroscience. 2007;144(1):325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robel P, Baulieu E-E. Neurosteroids: biosynthesis and function. Critical Reviews in Neurobiology. 1995;9(4):383–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HMA, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444(7118):486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu WJ, Vicini S. Neurosteroid prolongs GABAA channel deactivation by altering kinetics of desensitized states. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(11):4022–4031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04022.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbison AE. Physiological roles for the neurosteroid allopregnanolone in the modulation of brain function during pregnancy and parturition. Progress in Brain Research. 2001;133:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(01)33003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majewska MD, Harrison NL, Schwartz RD, Barker JL, Paul SM. Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor. Science. 1986;232(4753):1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.2422758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovick TA. GABA in the female brain—oestrous cycle-related changes in GABAergic function in the periaqueductal grey matter. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;90(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SS, Gong QH, Li X, et al. Withdrawal from 3α-OH-5α-pregnan-20-one using a pseudopregnancy model alters the kinetics of hippocampal GABAA-gated current and increases the GABAA receptor α4 subunit in association with increased anxiety. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18(14):5275–5284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05275.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiting PJ, McKernan RM, Wafford KA. Structure and pharmacology of vertebrate GABAA receptor subtypes. International Review of Neurobiology. 1995;38:95–138. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Follesa P, Serra M, Cagetti E, et al. Allopregnanolone synthesis in cerebellar granule cells: roles in regulation of GABAA receptor expression and function during progesterone treatment and withdrawal. Molecular Pharmacology. 2000;57(6):1262–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Follesa P, Concas A, Porcu P, et al. Role of allopregnanolone in regulation of GABAA receptor plasticity during long-term exposure to and withdrawal from progesterone. Brain Research Reviews. 2001;37(1–3):81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Smith DH, Gong QH, et al. Hormonally regulated α4β2δ GABAA receptors are a target for alcohol. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(8):721–722. doi: 10.1038/nn888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths J, Lovick T. Withdrawal from progesterone increases expression of α4, β1, and δ GABAA receptor subunits in neurons in the periaqueductal gray matter in female Wistar rats. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;486(1):89–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffiths JL, Lovick TA. GABAergic neurones in the rat periaqueductal grey matter express α4, β1 and δ GABAA receptor subunits: plasticity of expression during the estrous cycle. Neuroscience. 2005;136(2):457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovick TA, Paul NL. Co-localization of GABA with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-dependent diaphorase in neurones in the dorsolateral periaqueductal grey matter of the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;272(3):167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lovick TA, Griffiths JL, Dunn SM, Martin IL. Changes in GABAA receptor subunit expression in the midbrain during the oestrous cycle in Wistar rats. Neuroscience. 2005;131(2):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mody I. Aspects of the homeostaic plasticity of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition. Journal of Physiology. 2005;562(1):37–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mody I. Distinguishing between GABAA receptors responsible for tonic and phasic conductances. Neurochemical Research. 2001;26(8-9):907–913. doi: 10.1023/a:1012376215967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandler R, Shipley MT. Columnar organization in the midbrain periaqueductal gray: modules for emotional expression? Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17(9):379–389. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovick TA. Plasticity of GABAA receptor subunit expression during the oestrous cycle of the rat: implications for premenstrual syndrome in women. Experimental Physiology. 2006;91(4):655–660. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandler R, Depaulis A, Vergnes M. Identification of midbrain neurones mediating defensive behaviour in the rat by microinjections of excitatory amino acids. Behavioural Brain Research. 1985;15(2):107–119. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(85)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu CL, Jürgens U. Effects of chemical stimulation in the periaqueductal gray on vocalization in the squirrel monkey. Brain Research Bulletin. 1993;32(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90068-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan MM, Clayton CC. Defensive behaviors evoked from the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of the rat: comparison of opioid and GABA disinhibition. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;164(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schenberg LC, de Aguiar JC, Graeff FG. GABA modulation of the defense reaction induced by brain electrical stimulation. Physiology & Behavior. 1983;31(4):429–437. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones SL, Gebhart GF. Inhibition of spinal nociceptive transmission from the midbrain, pons and medulla in the rat: activation of descending inhibition by morphine, glutamate and electrical stimulation. Brain Research. 1988;460(2):281–296. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bee LA, Dickenson AH. Rostral ventromedial medulla control of spinal sensory processing in normal and pathophysiological states. Neuroscience. 2007;147(3):786–793. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kovelowski CJ, Ossipov MH, Sun H, Lai J, Malan TP, Jr., Porreca F. Supraspinal cholecystokinin may drive tonic descending facilitation mechanisms to maintain neuropathic pain in the rat. Pain. 2000;87(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen TS, Smith DF. Effect of emotions on nociceptive threshold in rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1982;28(4):597–599. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh RN, Cummins RA. The open-field test: a critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1976;83(3):482–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jørum E. Analgesia or hyperalgesia following stress correlates with emotional behavior in rats. Pain. 1988;32(3):341–348. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin VT, Lee J, Behbehani MM. Sensitization of the trigeminal sensory system during different stages of the rat estrous cycle: implications for menstrual migraine. Headache. 2007;47(4):552–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vinogradova EP, Zhukov DA, Batuev AS. The effects of stages of the estrous cycle on pain thresholds in female white rats. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology. 2003;33(3):269–272. doi: 10.1023/a:1022155432262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kayser V, Berkley KJ, Keita H, Gautron M, Guilbaud G. Estrous and sex variations in vocalization thresholds to hindpaw and tail pressure stimulation in the rat. Brain Research. 1996;742(1-2):352–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martínez-Gómez M, Cruz Y, Salas M, Hudson R, Pacheco P. Assessing pain threshold in the rat: changes with estrus and time of day. Physiology & Behavior. 1994;55(4):651–657. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frye CA, Cuevas CA, Kanarek RB. Diet and estrous cycle influence pain sensitivity in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;45(1):255–260. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90116-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hiroi R, Neumaier JF. Differential effects of ovarian steroids on anxiety versus fear as measured by open field test and fear-potentiated startle. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;166(1):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eikelis N, Van den Buuse M. Cardiovascular responses to open-field stress in rats: sex differences and effects of gonadal hormones. Stress. 2000;3(4):319–334. doi: 10.3109/10253890009001137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frye CA, Petralia SM, Rhodes ME. Estrous cycle and sex differences in performance on anxiety tasks coincide with increases in hippocampal progesterone and 3α,5α-THP. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000;67(3):587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mora S, Dussaubat N, Díaz-Véliz G. Effects of the estrous cycle and ovarian hormones on behavioral indices of anxiety in female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21(7):609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(96)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rudick CN, Woolley CS. Estrogen regulates functional inhibition of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells in the adult female rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(17):6532–6543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06532.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heinricher MM, Martenson ME, Neubert MJ. Prostaglandin E2 in the midbrain periaqueductal gray produces hyperalgesia and activates pain-modulating circuitry in the rostral ventromedial medulla. Pain. 2004;110(1-2):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marabese I, Rossi F, Palazzo E, et al. Periaqueductal gray metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7 and 8 mediate opposite effects on amino acid release, rostral ventromedial medulla cell activities, and thermal nociception. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2007;98(1):43–53. doi: 10.1152/jn.00356.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fairhurst M, Wiech K, Dunckley P, Tracey I. Anticipatory brainstem activity predicts neural processing of pain in humans. Pain. 2007;128(1-2):101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]