Abstract

Adhesion between epithelial cells mediates apical–basal polarization, cell proliferation, and survival, and defects in adhesion junctions are associated with abnormalities from degeneration to cancer. We found that the maintenance of specialized adhesions between cells of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) requires the phosphatase PTEN. RPE-specific deletion of the mouse pten gene results in RPE cells that fail to maintain basolateral adhesions, undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and subsequently migrate out of the retina entirely. These events in turn lead to the progressive death of photoreceptors. The C-terminal PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 (PDZ)-binding domain of PTEN is essential for the maintenance of RPE cell junctional integrity. Inactivation of PTEN, and loss of its interaction with junctional proteins, are also evident in RPE cells isolated from ccr2−/− mice and from mice subjected to oxidative damage, both of which display age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Together, these results highlight an essential role for PTEN in normal RPE cell function and in the response of these cells to oxidative stress.

Keywords: PI3K signaling, PTEN, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

The vertebrate retina is an exquisitely organized ensemble of neurons and glia, whose integrated activity eventually delivers visual information to the brain (Morrow et al. 1998; Livesey and Cepko 2001). Visual perception, however, requires not only this “neural retina,” but in addition, a set of large, neuroepithelially derived cells located at the back of the eye—the cells of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) (Bok 1993; Grierson et al. 1994; Marmorstein et al. 1998; Zarbin 1998; Adler et al. 1999; Schraermeyer and Heimann 1999). RPE cells, through their apical microvili, make extensive contacts with the opsin-containing outer segments of photoreceptors (Bok 1993; Rizzolo 1997; Marmorstein et al. 1998). This association enables these cells to exchange photopigments with, uptake metabolic wastes from, and transfer nutrients to photoreceptors. In addition, RPE cells perform a specialized form of phagocytosis in which the distal ends of photoreceptor outer segments are pinched off, engulfed, and metabolized on a daily basis (Young and Bok 1969; Edwards and Szamier 1977; Bok 1993). This homeostatic phagocytosis is critical, since defects in the process invariably lead to photoreceptor death (Young and Bok 1969; Edwards and Szamier 1977; Bok 1993). On their basal surfaces, RPE cells adhere to Bruch’s membrane, which separates them from the blood vessels that run just outside the retina (Bok 1993; Rizzolo 1997; Marmorstein et al. 1998; Zarbin 2004). These polarized features of the RPE, which are essential to its function, require specialized intercellular junctions (Rizzolo 1997; Jin et al. 2002).

Junctional structures depend upon cytoplasmic linker proteins that recruit cytoskeletal proteins to adhesion complexes (Vasioukhin et al. 2000; Jamora and Fuchs 2002; Perez-Moreno et al. 2003). β-Catenin, for example, associates with cadherins to form adherens junctions (AJs) on the lateral aspect of epithelial cells, and links the actin cytoskeleton to these junctions (Perez-Moreno et al. 2003). Alternatively, free β-catenin, generated by dissociation from cadherins in response to growth factor stimulation and oxidative stress, translocates to the nucleus, where it regulates genes that lead epithelial cells to re-enter the cell cycle. In some settings, this results in cancer (Barker and Clevers 2000).

Since RPE cells form an important component of the blood–retinal barrier (BRB), RPE damage or loss invariably results in retinal degeneration (Rizzolo 1997; Hamdi and Kenney 2003; Zarbin 2004). Although impairment of RPE structural integrity is known to lead to retinal degenerative diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and some forms of retinitis pigmentosa (RP), the molecular mechanisms that regulate RPE structure have remained elusive (Grierson et al. 1994; Zarbin 1998; Adler et al. 1999; Schraermeyer and Heimann 1999). One of the major causes of AMD is oxidative stress, which is generated both endogenously during the course of phototransduction, and also by a variety of exogenous insults (Cai et al. 2000; Bailey et al. 2004; Wenzel et al. 2005). AMD-inducing oxidative stresses impact the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–Akt pathway (Lee et al. 2002; Leslie et al. 2003; Yang et al. 2006; Barbieri et al. 2008), and it has been proposed that this pathway protects RPE cells against the deleterious effects of oxidative stress (Wang and Spector 2000; Defoe and Grindstaff 2004; Yang et al. 2006).

We investigated this hypothesis by inducing extended activation of the PI3K–Akt pathway in the mouse RPE through specific deletion of the phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (pten) gene. We find that PTEN inactivation leads to the progressive degeneration of both RPE cells and the photoreceptors with which they interact. PTEN-deficient RPE cells gradually lose their intercellular adhesions, undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and eventually disappear from the eye entirely. We also found that PTEN is physiologically inactivated in RPE cells isolated from ccr2−/− mice or from mice treated with an oxidative stressor, both of which exhibit retinal degeneration. We propose that PTEN plays a central role in normal retinal homeostasis, in the maintenance RPE cell polarity and integrity, and in the protection against oxidative stress-induced retinal degeneration.

Results

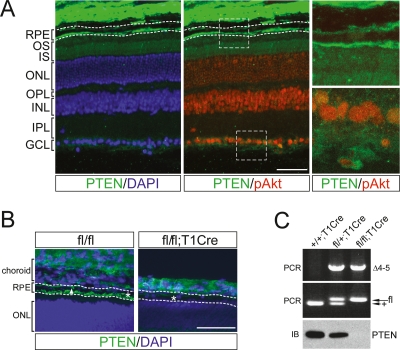

RPE-specific knockout of pten

We used immunostaining to examine the activity of the PI3K and Akt pathways in the adult mouse retina. We first assessed the distribution of phosphorylated Akt(S473; pAkt), which appears upon the activation of PI3K and the subsequent elevation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) levels in the plasma membrane (Cantley 2002). Phospho-Akt was concentrated in the inner nuclear layer (INL) and the ganglion cell layer (GCL) of the retina, with a relatively low signal in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the RPE layer (Fig. 1A, middle, right panels). When we examined the distribution of PTEN, whose phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase opposes PI3K (Salmena et al. 2008), we found an inverse pattern of expression (Fig. 1A,B). PTEN was highest in RPE layer, where the pAkt signal was relatively low, and lowest in the pAkt-enriched INL. PTEN was also high in RGC axons, where pAkt was low, and low in RGC cell bodies, where pAkt was high.

Figure 1.

RPE-specific deletion of mouse PTEN. (A) Expression of PTEN in the adult retina. A section of a 3-mo-old mouse eye was stained with mouse anti-PTEN antibody (green) with counter-nuclear staining with DAPI (blue, left panel). PTEN is enriched in the RPE layer where the signal for anti-phospho-Akt(S473) (pAkt; red, middle and right panels) is lowest. Boxed areas in the middle panel are enlarged in right panels to provide closer views to the costaining images of PTEN and pAkt at RPE–photoreceptor boundary (top right panel) and at GCL (bottom right panel). Upper and lower dashed lines represent basal and apical extents of the RPE layer, respectively. (OS) Photoreceptor outer segment; (IS) inner segment; (ONL) outer nuclear layer (photoreceptor nuclei); (OPL) outer plexiform layer; (INL) inner nuclear layer; (IPL) inner plexiform layer; (GCL) retinal ganglion cell layer. (B) PTEN localizes to apical microvilli (*) and basolateral areas (arrowhead) of RPE cells in P8 fl/fl mice. This signal is absent in fl/fl;T1Cre RPE cells, while PTEN in the choroids, sclera, or retina is intact. Upper and lower dashed lines represent basal and apical extents of the RPE layer, respectively. (C, top panel) RPE cells were isolated from P8 eyes, and Cre-mediated deletion of the genomic fragment spanning exons 4 and 5 of PTEN gene (Δ4–5) (Suzuki et al. 2001) was examined by PCR. The middle panel displays corresponding genotyping PCR using tail DNA, where Cre is not expressed. (Bottom panel) Loss of PTEN in the RPE was confirmed by immunoblot (IB) with PTEN antibody. Bars, 50 μm.

The RPE supports visual processes through the removal of spontaneously generated toxic metabolites and the phagocytic renewal of photoreceptor outer segments (Bok 1993; Grierson et al. 1994; Marmorstein et al. 1998; Zarbin 1998; Adler et al. 1999; Schraermeyer and Heimann 1999). Given the high level of PTEN in the RPE, we investigated its role in this epithelium by generating mice that lack the phosphatase specifically in RPE cells (Fig. 1B,C). Mice carrying a “floxed” pten allele were bred with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the RPE-restricted tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TRP1) promoter (Suzuki et al. 2001; Mori et al. 2002). As expected, exons 4 and 5 of PTEN gene, which are flanked by two loxP sites, were deleted in RPE cells isolated from PTENfl/fl;TRP1-Cre mice (fl/fl;T1Cre hereafter) (Fig. 1B,C), and these cells lacked PTEN protein. The mutant mice did not show any recognizable defects in embryonic development or reproduction.

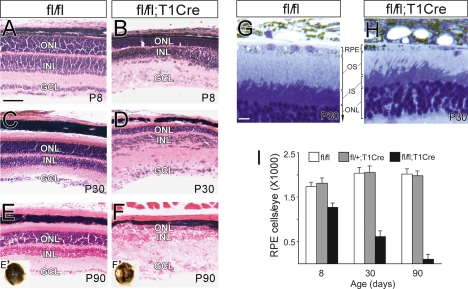

Photoreceptor degeneration and retinal depigmentation

The loss of PTEN from the RPE did not result in morphological defects in embryonic or neonatal (P0) eyes (data not shown). However, fl/fl;T1Cre retinae underwent progressive degeneration from this time forward (Fig. 2). Changes were first detected at 1 wk (P8), when local depigmentation associated with local collapse of RPE cells and choroids was detected in ∼17% of mutant eyes. ONL thickness, as well as the number of photoreceptors, was also reduced in the mutants, although all retinal cell types were present (Fig. 2A,B; Supplemental Fig. S1A,B). Morphological changes were more evident at 1 mo, when expansive depigmented areas and disorganization of retinal laminae were readily evident (Fig. 2C,D), and the total number of photoreceptors was markedly reduced (Supplemental Fig. S1A,B). By 3 mo, fl/fl;T1Cre retinae exhibited a dramatic loss of photoreceptors, and remaining retinal cells failed to form noticeable laminar structures (Fig. 2E,F). Most mutant eyes (∼78%) were obviously depigmented at this point (Fig. 2E′, F′,H). More than 90% of RPE cells were lost from 3-mo-old mutant eyes (Fig. 2I), but this cell loss did not appear to result from apoptotic cell death, since no elevation in the number of TUNEL-positive or activated caspase-3-positive cells (relative to wild type) was detected in the fl/fl;T1Cre mice at any stage (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Progressive RPE loss in fl/fl;T1Cre eyes. (A–F) H&E staining of fl/fl and fl/fl;T1Cre eye sections at the indicated postnatal (P) days. Images in E′ and F′ are lateral views of 3-mo-old f/fl and fl/fl;T1Cre eyes, respectively. (G, H) Osmium tetroxide staining of 1-mo-old f/fl and fl/fl;T1Cre eye sections. (I) Total RPE cells were purified from eyes at the indicated postnatal day, dissociated, and counted. (n ≥ 6) (see the Materials and Methods for details). Bars: A–F, 50 μm; G,H, 10 μm.

Retinal gliosis

Despite the severe loss of photoreceptors, the overall thickness of 3-mo-old mutant retinae was only slightly reduced relative to wild type (Fig. 2E,F). This discrepancy was accounted for by the proliferation of activated Müller glia (MG), marked by glutamine synthase (GS) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Supplemental Fig. S3A–D). The overproduction of MG in the mutant retina is common to many retinal degenerative diseases (Bringmann and Reichenbach 2001), and is normally induced by the inflammation that is triggered by infiltrating macrophages and monocytes. We monitored the distribution of macrophages by immunostaining with the pan-macrophage marker F8/40 (Malorny et al. 1986). F8/40-positive macrophages were confined outside of the RPE layer in wild-type mouse eyes, but were detected in the subretinal spaces and the inner plexiform layer (IPL) of fl/fl;T1Cre mouse retinae (data not shown).

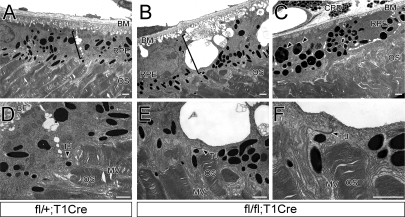

Loss of intercellular adhesions

In order to determine the origin of these degenerative events, we examined the ultrastructure of mutant and wild-type RPE cells by electron microscopy (EM) (Fig. 3). EM images of RPE cells from 4-wk-old fl/fl;T1Cre mice, which exhibited early-stage retinal degeneration, provided a comprehensive view of retinal degeneration in a single eye (Fig. 3B,C). Mutant eyes included a severely affected region, where most RPE cells and a substantial number of photoreceptors had degenerated, but also contained areas with a relatively intact RPE–photoreceptor interface (Fig. 3B,C). Closer examination of these intact areas revealed very different cellular structures from those seen in PTEN heterozygous RPE cells (Fig. 3D,E). Heterozygous RPE cells contacted each other with AJs and desmosomes at their lateral margins, and with intact tight junctions (TJs) at their apical margins (Fig. 3A,D). They also formed regular membrane folds along their basal surfaces contacting Bruch’s membrane. Although small vacuolar “bubbles” between lateral contacts in heterozygous RPE cells were not uncommon, these were enormously increased in PTEN-deficient RPE cells (brackets in Fig. 3A,B). Basolateral RPE adhesions were completely lost in the mutants, leaving only thin bands of cell-to-cell contact at apical TJs (Fig. 3E,F). In contrast, the apical microvilli of the mutant RPE cells projected normally, and made normal contacts with photoreceptor outer segments (Fig. 3E,F). These ultrastructural changes were accompanied by an abnormal subcellular distribution of marker proteins (Supplemental Fig. S4). Junctional localization of the AJ components β-catenin and E-cadherin was defective in PTEN-deficient RPE cells (Supplemental Fig. S4A–D), but the apical localization of Ezrin in the microvilli of mutant RPE cells that had not degenerated was normal (Supplemental Fig. S4E,F), as was that of zona occludens 1 (ZO1) and Crumb3 (Crb3), proteins that associate with TJs (Supplemental Fig. S4G–J). These data suggest that the progressive RPE degeneration and subsequent photoreceptor degeneration in the fl/fl;T1Cre mice begin with defects in basolateral junctional structures, which are followed by the disruption of apical structures and the subsequent loss of overall BRB integrity.

Figure 3.

Impaired intercellular adhesion between PTEN-deficient RPE cells. EM images from P28 fl/+;T1Cre (A,D), and fl/fl;T1Cre (B,C,E,F) mouse eyes. fl/+;T1Cre RPE cells form well-organized basolateral appositions (bracket in A), but PTEN-deficient RPE lose these appositions, resulting in large intercellular vacuoles (bracket in B). Basal folds of the mutant RPE cells, which contact Bruch’s membrane (BM), degenerate (B), and many RPE cells contain enlarged, dysmorphic pigment vesicles (arrowheads in C). (D,E) Magnified EM images of A, B, and E are shown in D, E, and F, respectively. (TJ) Tight junction; (MV) microvilli; (OS) outer segments; (CRD) choroid. Bars, 1 μm.

Localization of PTEN at junctional areas

We did not expect that basolateral structures would be most sensitive to the loss of PTEN, since PTEN is especially prominent in the apical membrane of RPE cells, as it is in many other epithelial cells (Pinal et al. 2006; Martin-Belmonte et al. 2007). We therefore re-examined the intracellular distribution of PTEN in vivo and in primary cultured RPE cells (Supplemental Fig. S5). PTEN was dispersed in the cytoplasm of RPE cells at P0, but was more apically concentrated at P8 (Supplemental Fig. S5A–D). Apical PTEN was maintained thereafter, expanding along microvilli by P28 (Supplemental Fig. S5E,F). PTEN could be also detected at the basolateral surfaces of P8 and P28 RPE cells (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S5C–F). Basolateral PTEN was more evident in cultured mouse RPE cells grown as a single layer on Matrigel (Supplemental Fig. S5G–I).

The localization and relative level of PTEN at the basolateral surface of RPE cells were further examined by differential fixation and detergent extraction (Supplemental Fig. S5J,K; see the Supplemental Material for details). The majority of PTEN was detected in the apical area, cytoplasm, and nuclei of RPE cells when primary cultured RPE cells were fixed prior to extraction with Triton X-100 (Supplemental Fig. S5J). PTEN at basolateral junctional structures was more obvious when RPE cells were subjected to extraction of apical, cytosolic, and soluble nuclear proteins prior to fixation (Supplemental Fig. S5K). Quantification of PTEN levels, assessed by densitometric measurement of band intensities on Western blots of the Triton X-100 soluble versus insoluble fraction, indicated that basolateral PTEN accounts for ∼25% of total PTEN in RPE cells (Supplemental Fig. S5L).

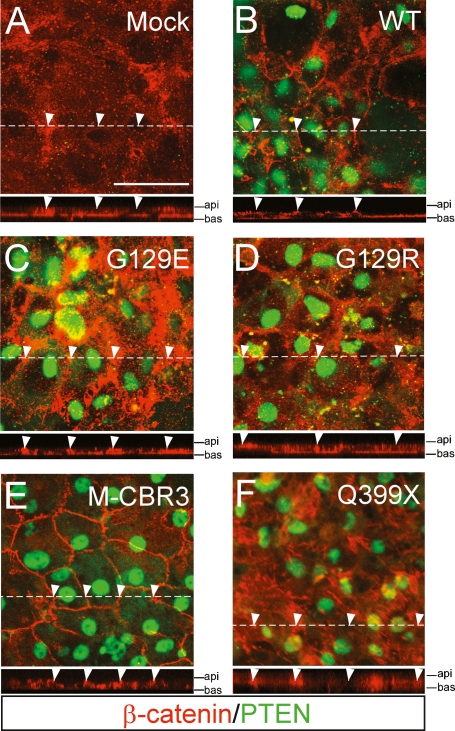

Junctional PTEN requires its C-terminal PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 (PDZ)-binding domain

PTEN possesses two enzymatic activities. One is a lipid phosphatase that acts on the 3-position of PIP3 to produce phosphatidylinositol-4,5 bisphosphates (PIP2), and the other is a protein phosphatase that preferentially dephosphorylates phosphotyrosine residues (Li et al. 1997; Myers et al. 1997; Steck et al. 1997; Maehama and Dixon 1998). To address the relative contribution of these two phosphatase activities to the maintenance of basolateral structures in RPE cells, retroviruses expressing various versions of human PTEN were used to infect cultured PTEN-deficient RPE cells isolated from fl/fl;T1Cre mice, and the subcellular distribution of β-catenin was monitored (Fig. 4). Infection with retroviruses expressing wild-type PTEN remobilized β-catenin to AJs from the cytoplasm and nuclei of PTEN-deficient RPE cells (Fig. 4A,B). A mutant PTEN lacking lipid phosphatase activity [PTEN(G129E)] (Furnari et al. 1997; Myers et al. 1998) was also able to remobilize β-catenin to AJs, although it was less effective than wild type (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. S6). However, PTEN(G129R), which lacks both lipid and protein phosphatase activity (Furnari et al. 1997), failed to remobilize β-catenin to AJs (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S6). These results suggest that PTEN regulates junctional structures through the dephosphorylation of substrate proteins, but also through local control of the balance between PIP2 and PIP3.

Figure 4.

The PDZ-binding domain of PTEN is essential for RPE AJs. RPE cells isolated from fl/fl;T1Cre mice were cultured on the Matrigel-coated transwell plates, and either mock-infected (A) or infected with retroviruses expressing wild-type PTEN (B), a lipid phosphatase-defective PTEN(G129E) mutant (C), a phosphatase-null PTEN(G129R) mutant (D), a mutant lacking lipid-binding C2 domains (M-CBR3; E), or a truncated PTEN mutant lacking the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain (Q399X; F). The localization of β-catenin in RPE cells was examined at 36 h of post-infection by immunostaining with anti-β-catenin antibody (red) and counterstaining with anti-PTEN antibody (green). For each panel, the fine dashed line indicates the position of the section for the orthogonal Z-stack displayed at the bottom of the panel, and arrowheads on the dashed line correspond to arrowheads in the bottom panel. Api and bas indicate apical and basal surfaces of the Z-stack. Bar, 50 μm.

We next sought to define the functional domains by which PTEN facilitates β-catenin relocalization to AJs (Fig. 4E,F). PTEN might localize to AJs through the binding to phospholipids with its C2 domain, or through the interaction of junctional PDZ domain-containing proteins with its C-terminal PDZ-binding domain (Georgescu et al. 1999, 2000; Lee et al. 1999; Leslie et al. 2000). Retroviruses expressing a mutant PTEN that lacks a functional C2 domain (PTEN M-CBR3) (Lee et al. 1999; Leslie et al. 2000) remobilized β-catenin to AJs even more efficiently than wild type PTEN in PTEN-deficient RPE cells (Fig. 4E; Supplemental Fig. S6). In contrast, PTEN(Q399X), which carries a nonsense mutation truncating the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain (Leslie et al. 2000), was unable to deliver cytoplasmic β-catenin to AJs (Fig. 4F). These results strongly suggest that the maintenance of AJs by PTEN requires interaction with PDZ domain-containing junctional proteins.

RPE inactivation of PTEN in mice undergoing retinal degeneration

To understand the molecular events that might lead to the structural changes documented above, we isolated total RNA from P21 wild-type or PTEN-deficient RPE cells, and analyzed gene expression profiles by Affymetrix microarrays (Supplemental Table S1). Consistent with the appearance of defective junctional structures in the mutant RPE cells, genes involved in cell-to-cell adhesion, including E-cadherin, desmoplakin, and plakophilin 3, were markedly reduced in their expression in the mutant RPE cells. Also reduced were genes tied to the inhibition of cell proliferation, such as transformation-related protein 63 (Trp63), p107Rb, and c-Cbl; genes regulating the extracellular matix (ECM), such as thrombospondin 4, dermatospondin, and syndecan1; and genes encoding intracellular chaperons, such as the heat-shock proteins Hspa1a, Hspa1b, Hspb1, and Dnaja4 (Supplemental Table S1). In contrast, the expression of genes associated with cell movement, such as α-smooth muscle actin/Actin A2a (α-SMA/ActA2a) and the myosin heavy chains Myh1 and Myh4, was markedly elevated in the mutant RPE cells (Supplemental Table S1).

Among the gene families that underwent the most dramatic changes were those encoding the crystallins and heat-shock proteins (HSPs). HSPs and crystallins protect cells against protein-destabilizing stressors, such as elevated temperature and reactive oxygen species (Horwitz 2000; Wang and Spector 2000; Bailey et al. 2004). RPE cells are continuously exposed to oxidative stress from the metabolic intermediates of photochemical reactions (Winkler et al. 1999; Cai et al. 2000), and excessive oxidative stress is known to be one of the major causes of retinal degenerative diseases such as AMD (Winkler et al. 1999; Beatty et al. 2000; Decanini et al. 2007).

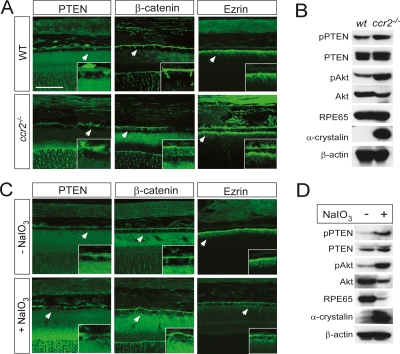

In order to assess any phenotypic similarity between PTEN-deficient RPE cells and AMD RPE cells, we monitored the cellular distribution of β-catenin and Ezrin in RPE cells of CC chemokine receptor 2-deficient (ccr2−/−) mice, which have been advanced as an AMD animal model (Fig. 5A; Ambati et al. 2003). An increased distribution of β-catenin in the cytoplasm coupled with normal localization of Ezrin in the apical microvilli, similar to that seen in PTEN-deficient RPE cells, was also observed in the cells of ccr2−/− mice (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Fig. S4B,F); and the immunofluorescent signal for PTEN at the apical and basolateral regions of ccr2−/− RPE cells was also strikingly reduced (Fig. 5A). However, the total amount of PTEN in RPE cells was not significantly changed (Fig. 5B). Instead, the level of phosphorylation of PTEN at S380, T382, or T383 (pPTEN), all of which decrease its association with PDZ domain proteins as well as its enzymatic activity (Vazquez et al. 2000; Tolkacheva et al. 2001), was substantially elevated in ccr2−/− RPE cells (Fig. 5B). Similar changes in these proteins were also observed in RPE cells of the ccl2−/− AMD mouse model (Ambati et al. 2003) (data not shown). These data suggest that the PTEN of ccr2−/− RPE cells is not able to integrate into junctional structures through its C-terminal PDZ-binding domain (Fig. 4E). This in turn suggests that either genetically or physiologically induced PTEN inactivation can result in AMD in mice.

Figure 5.

PTEN perturbation in RPE cells undergoing chemically and genetically induced retinal degeneration. (A) Frozen sections (10 μm) of 11-mo-old wild-type or ccr2−/− mouse eyes were stained with antibodies against PTEN, β-catenin, or Ezrin. (B) Relative proteins levels in RPE cells isolated from 11- to 12-mo-old wild-type or ccr2−/− mice were accessed by Western blotting with anti-phospho-PTEN(S380/T382/T383) (pPTEN), anti-PTEN (PTEN), anti-phospho-Akt(S473) (pAkt), anti-Akt (Akt), α-crystallin, or β-actin antibody. (C) C57/BL6 wild-type mice (3 mo old) were intravenously injected with NaIO3 (30 mg/kg), and the levels of pPTEN, pAkt, and β-catenin in RPE cells were monitored by immunostaining after 24 h. (D) The levels of pPTEN, PTEN, pAkt, Akt, α-crystallin, or β-actin in RPE cells from the NaIO3-injected mice were assessed by Western blotting. Arrowheads in A and C indicate the area magnified in each inset. Bar, 50 μm.

To address whether the inactivation of PTEN at junctional areas is an event commonly induced by AMD-triggering stimuli or an event that results from defects in Ccr2-activated signaling pathways unrelated to RPE degeneration, we induced RPE degeneration through oxidative stress. The oxidative stressor sodium iodate (NaIO3) has been used previously to induce selective degeneration of the RPE and consequent retinal degeneration (Ringvold et al. 1981; Kiuchi et al. 2002; Enzmann et al. 2006). Intravenous injection of NaIO3 into C57/BL6 mice induced disorganization of the RPE layer after 36 h, and subsequently led to the degeneration of photoreceptors. Reduced immunostaining for PTEN and cytoplasmic release of β-catenin from junctional areas were also observed in the RPE cells of these NaIO3-injected mice, similar to that seen in PTEN-deficient or ccr2−/− RPE cells (Fig. 5C). These events were also accompanied by an increased phosphorylation of PTEN and Akt (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the inactivation of PTEN and the consequent breakdown of AJs are not ccr2−/−-specific events, but rather reflect a common mechanism for RPE degeneration following oxidative stress.

PTEN-deficient RPE cells transform from epithelia to mesenchyme and form metastatic tumors

PTEN is a well-known tumor suppressor, and we found that a substantial fraction of fl/fl;T1Cre adult mice carried tumors. However, none of these tumors were intraocular. Instead, they appeared primarily in lymph nodes, but also in the colon, intestine, ovary, testis, and liver (Supplemental Fig. S7A; data not shown). Tumors were detected as early as 3 mo, but most were observed in mice older than 6 mo (Supplemental Fig. S7E). The spleen, where transformed RPE cells have been shown previously to metastasize and induce splenomegaly (Penna et al. 1998; Mori et al. 2002), contained only entrapped pigmented cells without any notable difference in size from wildtype (Supplemental Fig. S7C). Lymph node tumors and pigmented spleens included cells with recombined PTEN genes between the two loxP sites (Supplemental Fig. S7F). Since these tissues were negative for Cre expression, the tumors are most likely to have originated from infiltrating cells. This suggests that mutant cells, from the RPE or other TRP1-postive tissues, infiltrate into the blood or lymphatic vessels and migrate to the lymph nodes, from which they further migrate to other tissues to induce metastatic tumors.

Supporting this hypothesis, the level of genes specifically expressed in migratory mesenchymal cells was significantly increased in mutant RPE cells (Supplemental Table S1). These include muscle-specific genes, such as α-SMA/ActA2a, myosin heavy-chain genes Myh1 and Myh4, troponin C, and tropomyosin (Thiery 2003; Lee et al. 2006). The elevated expression of these genes is complemented by the reduced expression of epithelial-specific genes, including the junctional protein genes listed above. We confirmed increased expression of α-SMA and Myh1, and decreased expression of E-cadherin, desmoplakin, and Crumbs 3, by quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) and Western blotting (Fig. 6A,B).

Figure 6.

PTEN-deficient RPE cells lose epithelial properties and undergo an EMT. (A) Comparative analyses of gene expression patterns between wild-type (WT) and PTEN-deficient (KO) RPE cells using Q-PCR and microarrays (see Supplemental Table S1). Results are average values from triplicate (Q-PCR) or duplicate (microarray) analyses. (B) Equivalent amounts of total cell lysates from wild-type (fl/fl) or PTEN-deficient (fl/fl;T1Cre) mouse RPE cells were also analyzed by Western blotting. (C) RPE cells isolated from fl/fl, fl/+;T1Cre, or fl/fl;T1Cre mice were grown on Matrigel transwell plates for 2 wk, and the number of cells migrating into and through the Matrigel membrane were counted (see the Materials and Methods). (D) RPE cells from fl/fl mice form an epithelial sheet on Matrigel matrix, with an intact microfilament network, as monitored by FITC-labeled phalloidin (green), at cell-to-cell adhesion sites. Stress fibers were more prominent in PTEN-deficient RPE cells isolated from fl/fl;T1Cre mice. Nuclei of RPE cells in 3D culture are shown by DAPI staining (blue). Bar, 50 μm. (E-cad) E-cadherin; (β-catn) β-catenin; (DSP) desmoplakin; (Crb3) Crumbs 3; (α-SMA) α-smooth muscle actin; (vmntn) vimentin.

The elevation of mesenchymal genes and the concomitant reduction of epithelial genes in PTEN-deficient RPE cells are commonly linked to an EMT, which is observed during cancer development as well as in embryonic cell migration (Thiery 2003; Lee et al. 2006). Thus, the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics in PTEN-deficient RPE cells could be an initial event in metastatic tumor development in the mutant mice. We therefore examined the migratory ability of wild-type versus PTEN-deficient RPE cells in Matrigel invasion chambers (Fig. 6C,D). Wild-type RPE cells formed a single epithelial layer with strong cell-to-cell adhesion, and only marginally invaded the Matrigel membrane. In marked contrast, PTEN-deficient RPE cells migrated into the Matrigel after 7 d of culture, and then passed through it to grow on the lower chamber membrane. We observed an ∼30-fold increase in RPE cell migration upon PTEN inactivation (Fig. 6C). Wild-type RPE cells contained well-maintained actin filament networks linked to intercellular adhesions (Fig. 6D), while the actin filaments of PTEN-deficient RPE cells were absent from cell-to-cell contacts. They instead formed prominent stress fibers, which are often seen in highly migratory cells in culture (Fig. 6D). Together, these data suggest that PTEN-deficient RPE cells failed to maintain intercellular adhesions, underwent an EMT, and invaded the circulatory system to form metastatic tumors at distant sites.

To assess the potential importance of nuclear translocation of β-catenin, which was released from AJs to induce the expression of EMT-related genes (Yook et al. 2006), to these events, we crossed our RPE conditional PTEN mutants with a reporter line in which nuclear β-galactosidase (BAT-gal) expression is driven by β-catenin/T-cell factor (TCF)-responsive elements (Maretto et al. 2003). We found that the number of RPE cells containing BAT-gal was increased in fl/fl;T1Cre mice relative to fl/fl mice (Supplemental Fig. S8A). In contrast, the numbers of BAT-gal-positive cells in the ciliary body, which is enriched in Wnt signaling (Liu et al. 2006), was not significantly different (Supplemental Fig. S8B). This suggests that β-catenin/TCF-induced BAT-gal expression in PTEN-deficient RPE cells might depend not on Wnt signaling, but rather on Akt antagonism of glycogen synthase kinase β, which promotes the proteolytic degradation of cytosolic free β-catenin through phosphorylation (Cross et al. 1995; Aberle et al. 1997).

Discussion

The energy carried by light generates reactive oxidative species that can accumulate in the form of oxidized macromolecules in photoreceptors and RPE cells (Noell et al. 1966; Young and Bok 1969; Winkler et al. 1999; Wenzel et al. 2005). Genetic or age-dependent decreases in redox systems in photoreceptors or RPE cells often lead to the inefficient clearance of these agents, which promote retinal degeneration. Photoreceptors and RPE cells employ several mechanisms to protect themselves from oxidative byproducts. Photoreceptor-intrinsic survival programs, for example, protect photoreceptors from light-activated cell death (Doonan and Cotter 2004). In addition, photoreceptors transfer toxic metabolites to RPE cells, which are responsible for their elimination through metabolic conversion or delivery to the blood. RPE cells are also involved in the phagocytic elimination of dead or damaged photoreceptors (Young and Bok 1969; Edwards and Szamier 1977; Bok 1993). However, less is known about protective programs that are intrinsic to RPE cells, despite the fact that defects in these cells are major causes of retinal degenerative diseases such as AMD (Hamdi and Kenney 2003; Zarbin 2004; Sparrow and Boulton 2005). Our data now demonstrate that loss of PTEN activity in RPE cells, either by cell type-specific gene deletion or through functional inactivation brought on by oxidative stress, results in retinal degeneration that is initiated by a loss of structural integrity of PTEN-dependent intercellular adhesions.

The observation that PTEN is inactivated by NaIO3 links the pathology of retinal degenerative diseases to the cellular events, which we observed in PTEN-deficient RPE cells. Retinal degeneration in fl/fl;T1Cre mice shares many anatomical and physiological features with AMD, which is induced by the cumulative stress generated by oxidative metabolites (Zarbin 2004; Decanini et al. 2007). A gradual loss of RPE cells and a subsequent degeneration of photoreceptors, for example, are observed in both instances (Fig. 2; Supplemental Figs. S1, S2), as is macrophage infiltration into the retina, disruption of BRB structures, gliosis, and neovascularization (Supplemental Fig. S3; data not shown). This is also the case for regression of inter-RPE junctional structures (Figs. 3, 5; Supplemental Fig. S4). Finally, PTEN is inactivated and lost from junctional areas in AMD model ccr2−/− RPE cells, mimicking that seen in PTEN-deficient RPE cells (Fig. 5A). These multiple concordances suggest that depletion of PTEN function in RPE cells, either by somatic mutation or oxidative stress, can lead to AMD.

The molecular mechanisms that result in PTEN depletion and/or inactivation by NaIO3 and other AMD-triggering signals (such as cigarette smoking) remain to be elucidated. A recent report suggests a potential link between PI3K activation and AMD (Barbieri and Weksler 2007), in that extracts of tobacco smoke were found to activate Akt and disrupt intercellular junctional structures in endothelium, as we observe in PTEN-deficient and NaIO3-damaged RPE cells (Figs. 3, 5B; Supplemental Fig. S4). Together, these results suggest that oxidative stressors might activate PI3K–Akt signaling pathways in RPE cells to induce AMD pathology.

The phosphorylation of PTEN at S380/T382/T383 not only decreases its enzymatic activity, but also interferes with its association with PDZ domain-containing proteins (Adey et al. 2000; Vazquez et al. 2000). Consistent with this, we find that the concentration of PTEN at junctional areas is lost in ccr2−/− and NaIO3-treated RPE cells, even though the overall level of PTEN is not different from wild type (Fig. 5). Phosphorylation at these residues has been suggested to change the conformation of PTEN, burying the phosphatase active site and PDZ-binding domain inside a folded protein (Vazquez et al. 2001; Das et al. 2003). This would prevent the phosphorylated PTEN in ccr2−/− and NaIO3-treated RPE cells from participating in junctional events in a manner similar to that seen for PTEN that lacks a PDZ-binding domain entirely (Fig. 4). A recent report demonstrates the importance of the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain for the maintenance of epithelial features in chick primitive streak cells (Leslie et al. 2007). These findings, in concert with our observations, emphasize the critical role that PTEN plays in the organization of epithelial junctional structures.

PTEN is also thought to regulate junctional structures by dephosphorylating junctional proteins and by generating PIP2 from PIP3 (Tamura et al. 1998; Kotelevets et al. 2001, 2005). Our demonstration that junctional β-catenin is recovered by reintroduction of PTEN(G129E), a mutant that possesses protein phosphatase activity, strongly suggests that this activity plays a important role in the maintenance of intercellular junctional structures at least in part (Fig. 4). Leslie et al. (2007) similarly have found that the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN is necessary for the suppression of EMT, while its lipid phosphatase activity is dispensable.

Little is known about the PTEN substrates that mediate epithelial cell junctional integrity (Salmena et al. 2008). We found that tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin, which is a recognized PTEN substrate (Vogelmann et al. 2005), was increased in PTEN-deficient RPE cells (Supplemental Fig. S9A). Hyperphosphorylation of β-catenin on tyrosine residues decreases its binding affinity for E-cadherin, and releases it into cytoplasm (Lilien and Balsamo 2005; Vogelmann et al. 2005); and the binding of the E-cadherin cytoplasmic domain to β-catenin was reduced in PTEN-deficient RPE cells compared with wild-type RPE (Supplemental Fig. S9B). These results suggest that PTEN complexes with AJ components via its PDZ-binding domain, and dephosphorylates junctional proteins, including β-catenin, thereby promoting their stable association with E-cadherin. At the same time, PTEN also converts PIP3, which is usually higher at cell-to-cell contact regions in epithelial cells (Kotelevets et al. 2005; Martin-Belmonte et al. 2007), to PIP2, which inhibits downstream events that are normally activated by PIP3.

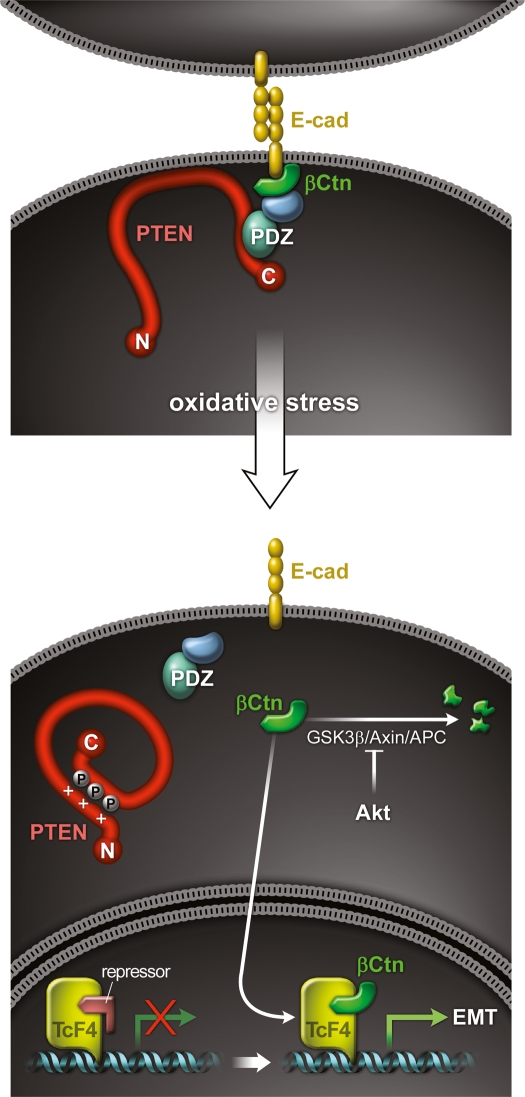

As summarized in Figure 7, our results indicate that PTEN is located at a pivotal node in the RPE cell signaling pathways that regulate junctional integrity. Oxidative stressors, which accumulate during phototransduction, activate signaling pathways that induce the inactivation of PTEN by phosphorylation. A reduction in PTEN activity results in a shift in signaling, from the maintenance to the disruption of intercellular junctional structures. At the same time, the same oxidative stressors trigger the RPE degeneration that underlies many retinal degenerative diseases.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of pathological signaling pathways in PTEN-inactivated RPE cells. (Top) PTEN normally functions as a component of AJs in healthy RPE cells, through its interaction with junctional PDZ proteins. This requires the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain of PTEN. (Bottom) PTEN is lost from junctional structures by phosphorylational inactivation upon oxidative stress or somatic mutation. β-Catenin is then released from dissociated junctional complexes, and enters the nucleus. RPE cells are thereby transformed into highly migratory mesenchymal cells, through β-catenin/TCF induction of new mesenchymal genes.

Materials and methods

Mouse lines

PTENflox mice (Suzuki et al. 2001) were bred with TRP1-Cre mice (Mori et al. 2002) to generate PTENflox/flox;TRP1-Cre (fl/fl;T1Cre) mice. Ccr2−/− and Ccl2−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories.

DNA constructs

cDNA clones of PTEN(399X) and PTEN(M-CBR3) were obtained by generous gifts from Dr. Nick Leslie (University of Dundee), and were subcloned into the EcoRI/SalI site of the pBabe-Puro retroviral vector for the generation of retroviruses expressing deletion mutant PTEN genes. pBabe-Puro constructs expressing PTEN, PTEN(G129R), or PTEN(G129E) were obtained from Dr. Frank Furnari (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, University of California at San Diego).

RPE isolation, primary cell culture, and Matrigel invasion assays

Primary mouse RPE cells were isolated from p21 wild-type or PTENfl/fl;TRP1-Cre mice as described (Bonilha et al. 1999; Prasad et al. 2006). In brief, enucleated eyes were treated with hyaluronidase (200 U/mL) for 30 min before treatment with trypsin (2 mg/mL) for 30 min. Cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 5 min, and pigmented RPE cells were counted with a hemocytometer. Isolated RPE cells (∼103) then plated on 10-mm Matrigel-coated transwell plates (BD) in Dulbecco’s modified eagles media (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). After reaching confluence, cells were infected with retroviruses or treated with chemical reagents. For invasion analyses, RPE cells grown on Matrigel transwells were scraped away with a cotton bar, and the Matrigel membranes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS (PFA/PBS) followed by staining with DAPI to monitor cells that had invaded the filters. The numbers of cells inside or on the opposite side of the membranes were added to the numbers of cells located at the well bottom to yield total invasive cells.

Retrovirus preparation and infection

Phoenix cells, which were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS, were transfected with pBabe-Puro-PTEN DNA constructs to produce retroviruses expressing wild-type or mutant versions of PTEN. Forty-eight hours after transfection, culture medium was collected and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Millipore) followed by mixing with 10 μg/mL polybrene (Specialty Media) prior to application to primary cultured RPE cells. Medium containing viruses was removed after 12 h, and then changed to fresh DMEM with 10% FBS prior to incubation for a further 24 h.

Antibodies and immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry of frozen sections, mice were anesthetized with tribromoethanol (1 mg/kg; Aldrich) and perfused with 4% PFA/PBS. Isolated eyes were further fixed with 4% PFA/PBS for 1 h prior to incubation in 20% sucrose/PBS for 16 h followed by freezing in OCT cryopreservation medium. Frozen sections of OCT-embedded eyes were incubated in blocking solution—10% normal donkey serum or 10% normal goat serum in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100—for 1 h prior to incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C for 16 h The primary antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Fluorescent images were obtained with a confocal microscope (LSM510; Zeiss) after staining with Alexa488 (Molecular Probes) or Cy3-conjugated (Jackson Laboratory) anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies for 1 h.

Immunotaining of primary cultured RPE cells grown on Matrigel transwell plates was conducted as described (Bonilha et al. 1999). Briefly, confluent RPE cells on Matrigel were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS with Ca2+/Mg2+ (PBS-CM) for 10 min, and treated with 4% PFA in PBS-CM for 10 min, and 4% PFA in PBS-CM and 1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Cells were stained with appropriate antibodies.

NaIO3 injection and RPE lysate preparation

C57/BL6 mice (2 to 3 mo) were injected with NaIO3 solution (30 mg/kg in PBS) into tail veins as described previously (Kiuchi et al. 2002; Enzmann et al. 2006). Eyes were enucleated and the retina carefully pushed out before treating with dispase (100 U/mL) to isolate RPE cells. RPE cells were then lysed in a solution containing 100 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche). Supernatants were obtained by centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 min, and were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Pierre Chambon for the generous gift of TRP1-Cre mice, Dr. Stefano Piccolo for BAT-gal mice, Dr. Nick Leslie for human PTEN and its mutant clones, Dr. Frank Furnari for pBabe-Puro-PTEN and mutant constructs, Dr. Masatoshi Takeichi for GST-E-cadherin, Dr. Benjamin Margolis for Crb3 antibody, and Joe Hash and Namsuk Kim for outstanding technical support. This work was supported by the Research Program for New Drug Target Discovery (M10748000222-08N4800-22210; J.W.K.) and Stem Cell Research (M10641000055-07N4100-05510; J.W.K.), grants from the Korean Ministry of Science and Technology (CDA0004/2007-C; J.W.K), an HFSP Career Development Award (J.W.K.), and the NIH (G.L.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1700108.

References

- Aberle H., Bauer A., Stappert J., Kispert A., Kemler R. β-Catenin is a target for the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adey N.B., Huang L., Ormonde P.A., Baumgard M.L., Pero R., Byreddy D.V., Tavtigian S.V., Bartel P.L. Threonine phosphorylation of the MMAC1/PTEN PDZ binding domain both inhibits and stimulates PDZ binding. Cancer Res. 2000;60:35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R., Curcio C., Hicks D., Price D., Wong F. Cell death in age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 1999;5:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambati J., Anand A., Fernandez S., Sakurai E., Lynn B.C., Kuziel W.A., Rollins B.J., Ambati B.K. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T.A., Kanuga N., Romero I.A., Greenwood J., Luthert P.J., Cheetham M.E. Oxidative stress affects the junctional integrity of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:675–684. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri S.S., Weksler B.B. Tobacco smoke cooperates with interleukin-1β to alter β-catenin trafficking in vascular endothelium resulting in increased permeability and induction of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in vitro and in vivo. FASEB J. 2007;8:1831–1843. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7557com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri S.S., Ruggiero L., Tremoli E., Weksler B.B. Suppressing PTEN activity by tobacco smoke plus interleukin-1β modulates dissociation of VE-cadherin/β-catenin complexes in endothelium. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:732–738. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N., Clevers H. Catenins, Wnt signaling and cancer. Bioessays. 2000;22:961–965. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200011)22:11<961::AID-BIES1>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty S., Koh H., Phil M., Henson D., Boulton M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok D. The retinal pigment epithelium: A versatile partner in vision. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 1993;17:189–195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1993.supplement_17.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha V.L., Finnemann S.C., Rodriguez-Boulan E. Ezrin promotes morphogenesis of apical microvilli and basal infoldings in retinal pigment epithelium. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:1533–1548. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann A., Reichenbach A. Role of Muller cells in retinal degenerations. Front. Biosci. 2001;6:E72–E92. doi: 10.2741/bringman. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Nelson K.C., Wu M., Sternberg P., Jones D.P. Oxidative damage and protection of the RPE. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2000;19:205–221. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley L.C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross D.A., Alessi D.R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B.A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Dixon J.E., Cho W. Membrane-binding and activation mechanism of PTEN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:7491–7496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decanini A., Nordgaard C.L., Feng X., Ferrington D.A., Olsen T.W. Changes in select redox proteins of the retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007;143:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoe D.M., Grindstaff R.D. Epidermal growth factor stimulation of RPE cell survival: Contribution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Exp. Eye Res. 2004;79:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doonan F., Cotter T.G. Apoptosis: A potential therapeutic target for retinal degenerations. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2004;1:41–53. doi: 10.2174/1567202043480215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R.B., Szamier R.B. Defective phagocytosis of isolated rod outer segments by RCS rat retinal pigment epithelium in culture. Science. 1977;197:1001–1003. doi: 10.1126/science.560718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzmann V., Row B.W., Yamauchi Y., Kheirandish L., Gozal D., Kaplan H.J., McCall M.A. Behavioral and anatomical abnormalities in a sodium iodate-induced model of retinal pigment epithelium degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;82:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari F.B., Lin H., Huang H.S., Cavenee W.K. Growth suppression of glioma cells by PTEN requires a functional phosphatase catalytic domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:12479–12484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu M.M., Kirsch K.H., Akagi T., Shishido T., Hanafusa H. The tumor-suppressor activity of PTEN is regulated by its carboxyl-terminal region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:10182–10187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu M.M., Kirsch K.H., Kaloudis P., Yang H., Pavletich N.P., Hanafusa H. Stabilization and productive positioning roles of the C2 domain of PTEN tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7033–7038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson I., Hiscott P., Hogg P., Robey H., Mazure A., Larkin G. Development, repair and regeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye. 1994;8:255–262. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi H.K., Kenney C. Age-related macular degeneration: A new viewpoint. Front. Biosci. 2003;8:305–314. doi: 10.2741/1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz J. The function of α-crystallin in vision. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;11:53–60. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamora C., Fuchs E. Intercellular adhesion, signalling and the cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M., Barron E., He S., Ryan S.J., Hinton D.R. Regulation of RPE intercellular junction integrity and function by hepatocyte growth factor. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:2782–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi K., Yoshizawa K., Shikata N., Moriguchi K., Tsubura A. Morphologic characteristics of retinal degeneration induced by sodium iodate in mice. Curr. Eye Res. 2002;25:373–379. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.25.6.373.14227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelevets L., van Hengel J., Bruyneel E., Mareel M., van Roy F., Chastre E. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for stabilizing intercellular junctions and reverting invasiveness. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:1129–1135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelevets L., van Hengel J., Bruyneel E., Mareel M., van Roy F., Chastre E. Implication of the MAGI-1b/PTEN signalosome in stabilization of adherens junctions and suppression of invasiveness. FASEB J. 2005;19:115–117. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1942fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.O., Yang H., Georgescu M.M., Di Cristofano A., Maehama T., Shi Y., Dixon J.E., Pandolfi P., Pavletich N.P. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: Implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell. 1999;99:323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.R., Yang K.S., Kwon J., Lee C., Jeong W., Rhee S.G. Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20336–20342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.M., Dedhar S., Kalluri R., Thompson E.W. The epithelia–mesenchymal transition: New insights in signaling, development, and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:973–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie N.R., Gray A., Pass I., Orchiston E.A., Downes C.P. Analysis of the cellular functions of PTEN using catalytic domain and C-terminal mutations: Differential effects of C-terminal deletion on signalling pathways downstream of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 2000;346:827–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie N.R., Bennett D., Lindsay Y.E., Stewart H., Gray A., Downes C.P. Redox regulation of PI 3-kinase signalling via inactivation of PTEN. EMBO J. 2003;22:5501–5510. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie N.R., Yang X., Downes C.P., Weijer C.J. PtdIns(3,4,5)P(3)-dependent and -independent roles for PTEN in the control of cell migration. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yen C., Liaw D., Podsypanina K., Bose S., Wang S.I., Puc J., Miliaresis C., Rodgers L., McCombie R., et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilien J., Balsamo J. The regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion by tyrosine phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of β-catenin. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Thurig S., Mohamed O., Dufort D., Wallace V.A. Mapping canonical Wnt signaling in the developing and adult retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:5088–5097. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey F.J., Cepko C.L. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: Lessons from the retina. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T., Dixon J.E. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malorny U., Michels E., Sorg C. A monoclonal antibody against an antigen present on mouse macrophages and absent from monocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 1986;243:421–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00251059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretto S., Cordenonsi M., Dupont S., Braghetta P., Broccoli V., Hassan A.B., Volpin D., Bressan G.M., Piccolo S. Mapping Wnt/β-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein A.D., Finnemann S.C., Bonilha V.L., Rodriguez-Boulan E. Morphogenesis of the retinal pigment epithelium: Toward understanding retinal degenerative diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;857:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Belmonte F., Gassama A., Datta A., Yu W., Rescher U., Gerke V., Mostov K. PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M., Metzger D., Garnier J.M., Chambon P., Mark M. Site-specific somatic mutagenesis in the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:1384–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow E.M., Furukawa T., Cepko C.L.1998Vertebrate photoreceptor cell development and disease Trends Cell Biol. 8353–358. . 7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M.P., Stolarov J.P., Eng C., Li J., Wang S.I., Wigler M.H., Parsons R., Tonks N.K. P-TEN, the tumor suppressor from human chromosome 10q23, is a dual-specificity phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:9052–9057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M.P., Pass I., Batty I.H., Van der Kaay J., Stolarov J.P., Hemmings B.A., Wigler M.H., Downes C.P., Tonks N.K. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor supressor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noell W.K., Walker V.S., Kang B.S., Berman S. Retinal damage by light in rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. 1966;5:450–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna D., Schmidt A., Beermann F. Tumors of the retinal pigment epithelium metastasize to inguinal lymph nodes and spleen in tyrosinase-related protein 1/SV40 T antigen transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1998;17:2601–2607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moreno M., Jamora C., Fuchs E. Sticky business: Orchestrating cellular signals at adherens junctions. Cell. 2003;112:535–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinal N., Goberdhan D.C., Collinson L., Fujita Y., Cox I.M., Wilson C., Pichaud F. Regulated and polarized PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 accumulation is essential for apical membrane morphogenesis in photoreceptor epithelial cells. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad D., Rothlin C.V., Burrola P., Burstyn-Cohen T., Lu Q., de Garcia Frutos P., Lemke G. TAM receptor function in the retinal pigment epithelium. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006;33:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringvold A., Olsen E.G., Flage T. Transient breakdown of the retinal pigment epithelium diffusion barrier after sodium iodate: A fluorescein angiographic and morphological study in the rabbit. Exp. Eye Res. 1981;33:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(81)80088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolo L.J. Polarity and the development of the outer blood–retinal barrier. Histol. Histopathol. 1997;12:1057–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmena L., Carracedo A., Pandolfi P.P. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraermeyer U., Heimann K. Current understanding on the role of retinal pigment epithelium and its pigmentation. Pigment Cell Res. 1999;12:219–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1999.tb00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow J.R., Boulton M. RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal pathobiology. Exp. Eye Res. 2005;80:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck P.A., Pershouse M.A., Jasser S.A., Yung W.K., Lin H., Ligon A.H., Langford L.A., Baumgard M.L., Hattier T., Davis T., et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Yamaguchi M.T., Ohteki T., Sasaki T., Kaisho T., Kimura Y., Yoshida R., Wakeham A., Higuchi T., Fukumoto M., et al. T cell-specific loss of Pten leads to defects in central and peripheral tolerance. Immunity. 2001;14:523–534. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M., Gu J., Matsumoto K., Aota S., Parsons R., Yamada K.M. Inhibition of cell migration, spreading, and focal adhesions by tumor suppressor PTEN. Science. 1998;280:1614–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery J.P. Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkacheva T., Boddapati M., Sanfiz A., Tsuchida K., Kimmelman A.C., Chan A.M. Regulation of PTEN binding to MAGI-2 by two putative phosphorylation sites at threonine 382 and 383. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4985–4989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin V., Bauer C., Yin M., Fuchs E. Directed actin polymerization is the driving force for epithelial cell–cell adhesion. Cell. 2000;100:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F., Ramaswamy S., Nakamura N., Sellers W.R. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail regulates protein stability and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:5010–5018. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5010-5018.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F., Grossman S.R., Takahashi Y., Rokas M.V., Nakamura N., Sellers W.R. Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail acts as an inhibitory switch by preventing its recruitment into a protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48627–48630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelmann R., Nguyen-Tat M.D., Giehl K., Adler G., Wedlich D., Menke A. TGFβ-induced downregulation of E-cadherin-based cell–cell adhesion depends on PI3-kinase and PTEN. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4901–4912. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Spector A. α-Crystallin prevents irreversible protein denaturation and acts cooperatively with other heat-shock proteins to renature the stabilized partially denatured protein in an ATP-dependent manner. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4705–4712. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel A., Grimm C., Samardzija M., Reme C.E. Molecular mechanisms of light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis and neuroprotection for retinal degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2005;24:275–306. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler B.S., Boulton M.E., Gottsch J.D., Sternberg P. Oxidative damage and age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 1999;5:32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P., Peairs J.J., Tano R., Jaffe G.J. Oxidant-mediated Akt activation in human RPE cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:4598–4606. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yook J.I., Li X.Y., Ota I., Hu C., Kim H.S., Kim N.H., Cha S.Y., Ryu J.K., Choi Y.J., Kim J., et al. A Wnt–Axin2–GSK3β cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R.W., Bok D. Participation of the retinal pigment epithelium in the rod outer segment renewal process. J. Cell Biol. 1969;42:392–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.2.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbin M.A. Age-related macular degeneration: Review of pathogenesis. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 1998;8:199–206. doi: 10.1177/112067219800800401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbin M.A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004;122:598–614. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]