Abstract

The structure-activity relationships of organophosphorus (OP) and organosulfur compounds were examined in vitro and in vivo as inhibitors of mouse brain monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) hydrolysis of 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and agonist binding at the CB1 receptor. Several compounds showed exceptional potency towards MAGL activity with IC50 values of 0.1-10 nM in vitro and high inihibition at 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally in mice. We find for the first time that MAGL activity is a major in vivo determinant of 2-AG and arachidonic acid levels not only in brain but also in spleen, lung and liver. Apparent direct OP inhibition of CB1 agonist binding may be due instead to metabolic stabilization of 2-AG in brain membranes as the actual inhibitor.

Keywords: Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors, 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, Arachidonic acid

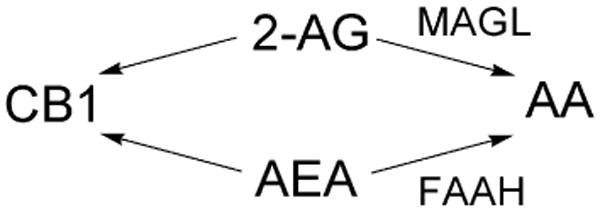

The endocannabinoids (EC) 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA) regulate a diverse array of neurological and metabolic functions and are altered by neuropathic pain, anxiety, neurodegeneration, obesity and cardiovascular disorders.1 2-AG is a full agonist towards the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) and its signaling is terminated primarily by monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL). AEA levels are regulated by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH).2-4 Augmentation of EC signaling by blockade of 2-AG or AEA degradation (Scheme 1) is proposed as a therapeutic strategy. However, characterization of MAGL or 2-AG in brain and peripheral tissues is hindered by the paucity of systemic MAGL inhibitors and lack of a MAGL knockout mouse. Discovery of potent MAGL inhibitors is therefore essential in understanding the biochemical, physiological and therapeutic roles of this enzyme.

Scheme 1.

Endocannabinoids 2-AG and AEA are agonists towards CB1 and are metabolized by MAGL and FAAH, respectively, to arachidonic acid (AA).

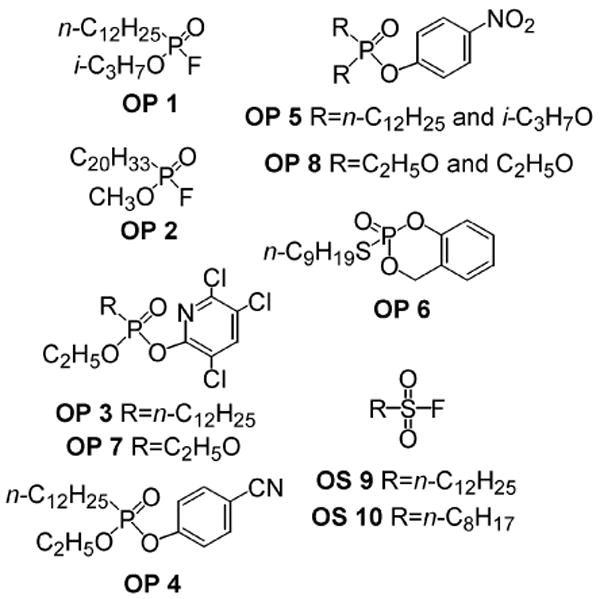

Structural manipulation of organophosphorus (OP) and organosulfur (OS) compounds (Scheme 2) can potentially confer potency and selectivity for MAGL and FAAH compared to other serine hydrolases. OP 1 and OP 2 are previously reported highly potent MAGL and FAAH inhibitors.3, 4 However, some OPs and OSs also displace CB1 agonist binding through an unknown mechanism.5

Scheme 2.

Organophosphorus (OP 1-8) and organosulfur (OS 9 and 10) compounds used in this study. In earlier literature OP 1, OP 2, OP 7 and OP 8 are referred to as IDFP, MAFP, chlorpyrifos oxon and paraoxon, respectively.4-6

This study reports structure-activity relationships of OPs and OSs with MAGL, FAAH and CB1 and uses these tools to consider three interrelationships of the EC system components. The first is the in vitro potency for inhibiting MAGL, FAAH and CB1 agonist binding as a predictor of in vivo behavioral effects and pharmacological profile. The second is the variation among tissues in their MAGL activity and differential regulation of 2-AG and AA levels. Finally we consider the possibility that OP displacement of CB1 agonist binding is due to 2-AG in membranes metabolically stabilized by MAGL inhibition.

A library of 40 OPs and OSs, mostly prepared and optimized in the Berkeley laboratory,7 was tested for potency and selectivity as inhibitors of MAGL, FAAH and CB1 agonist binding in mouse brain membranes.8 Five particularly potent OPs for all three targets were phosphonyl fluorides 1 and 2 and aryl phosphorus compounds 3-6, all with long alkyl substituents [n-C12H25P, arachidonyl (C20H33P) or n-C9H19SP] (Table 1; Supplementary data). One diethyl phosphate insecticide metabolite (OP 7) was quite potent and another (OP 8) was only moderately active. Two sulfonyl fluorides (9 and 10) with long alkyl chains were very potent on FAAH, moderately active on MAGL and differed greatly in activity on CB1.

Table 1.

Inhibitory potencies of OPs and OSs for mouse brain MAGL and FAAH activities and CB1 agonist binding

| IC50 (nM) ± S.D. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | MAGL | FAAH | CB1 |

| Phosphonyl fluorides | |||

| OP 1 | 0.8 ± 0.2a | 3 ± 2a | 2 ± 1 |

| OP 2 | 2.2 ± 0.3a | 0.10 ± 0.02a | 20a |

| Aryl phosphorus compounds | |||

| OP 3 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 42 ± 12 | 14 ± 5 |

| OP 4 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 12± 3 | 4 ± 2 |

| OP 5 | 0.28 ± 0.23 | 3 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 |

| OP 6 | 0.31 ± 0.03a | 0.15 ± 0.01a | |

| Insecticide metabolites | |||

| OP 7 | 10 ± 4a | 40 ± 3a | 14 ± 3 |

| OP 8 | 2300 ± 1100a | 540a | 1200a |

| Sulfonyl fluorides | |||

| OS 9 | 200 ± 75a | 2a | 7 ± 4 |

| OS 10 | 140 ± 2a | 1.9 ± 0.2a | 1300 ± 300 |

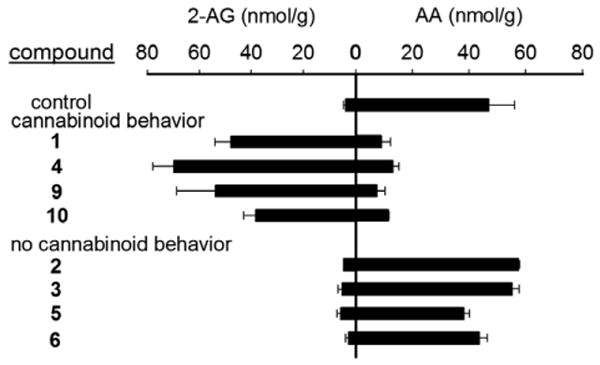

Eight potent in vitro inhibitors were administered intraperitoneally to mice at 10 mg/kg (OPs 1-6) or 100 mg/kg (OS 9 and OS 10) to determine if they were also effective in vivo in modulating behavior and brain 2-AG and arachidonic acid (AA) levels (Fig. 1). OP 1 and OP 4 were very effective in vivo in all respects whereas OP 2 and OP 3 with similar in vitro potency to 1 and 4 were not effective in vivo. Thus, in vitro potency is not necessarily a predictor of in vivo activity with metabolic stability a likely contributor. OS 9 and OS 10 gave the same in vivo effects as OP 1 and OP 4 although at a 10-fold higher dose. Importantly, the OP- and OS-induced increase in brain 2-AG levels was always directly related to the lowering of brain free AA level.

Figure 1.

Modulatory action of OP MAGL inhibitors at 10 mg/kg and OS compounds 9 and 10 at 100 mg/kg on brain 2-AG and AA levels relative to cannabinoid behavior. Mice with cannabinoid behavior had >10 s latency in the bar test which assesses catalepsy.10 They also qualitatively had a flattened posture and remained motionless with their eyes open. Values are mean ± S.D., n=3 mice/treatment group.

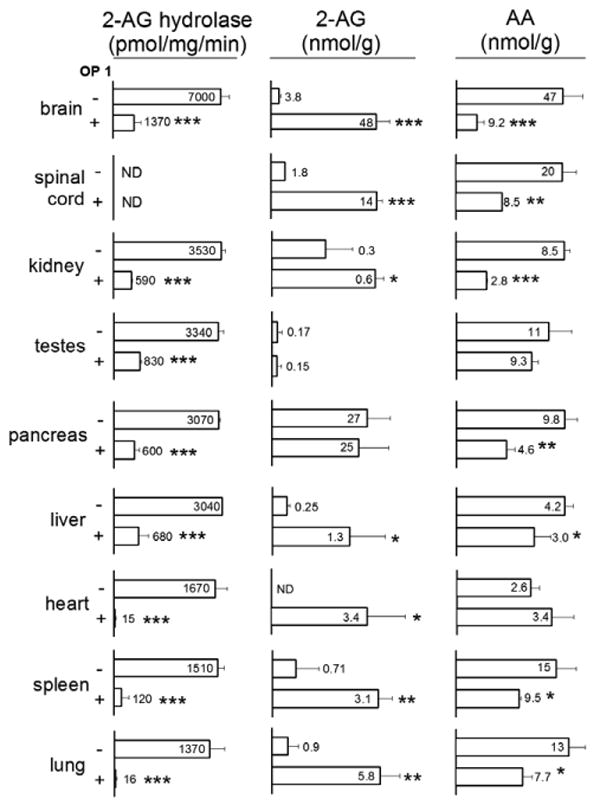

2-AG and AA are important signaling molecules and intermediates not only in brain but also in other tissues.1, 2, 11 OP 1 at 10 mg/kg strongly inhibits brain MAGL activity, elevates 2-AG and lowers AA4 suggesting that it might also do so in other tissues (Fig. 2). 2-AG hydrolase activity was higher in brain than other tissues examined with 78-83 % sensitive to OP 1 in vivo in brain, kidney, testes, pancreas and liver and 92-99 % OP 1-sensitive in vivo in heart, spleen and lung. The apparent coupling of 2-AG and AA levels was also examined. Among the tissues analyzed, brain, spinal cord, liver, spleen and lung, but not kidney, testes, pancreas or heart showed the possible codependence of 2-AG and AA pools (Fig. 2 and Supplementary data). Most tissues also had increased levels of other monoacylglycerol species, i.e. 1- and 2-palmitoylglycerol and 1- and 2-oleoylglycerol (Supplementary data). Beyond changes in glycerol esters and AA levels, OP 1 treatment also led to decreases in other unesterified fatty acid levels (palmitic, oleic or stearic acid) in spinal cord, liver and spleen, indicating off-target effects of OP 1 in these tissues. The heart interestingly showed increases in both oleic and stearic acids (Supplementary data).

Figure 2.

2-AG hydrolase activities and 2-AG and AA levels in mice treated with OP 1 (10 mg/kg, ip 4h).12 Values are expressed as mean ± S.D., n=3 mice/treatment group. ND, not determined. Significance expressed as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 in unpaired Student's t-test.

Our results confirm the coordinate regulation of 2-AG and AA levels by MAGL in brain4 and show that this regulation also exists in some peripheral tissues. These findings disfavor the current model in which AA in many tissues is released primarily through glycerophospholipid metabolism via multiple phospholipase A2 enzymes, notably cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) and calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2). While there are multiple studies correlating increased PLA2 expression to pro-inflammatory outcomes, cPLA2 -/- mice (also deficient in sPLA2) have identical levels of plasma and brain nonesterified fatty acid levels and brain acyl-coenzyme A levels, albeit there were changes in esterified phospholipid levels.13 Although OP 1 is not completely selective for MAGL, it does not inhibit iPLA24 and the degree to which OPs 1, 4, 9 and 10 lower AA is equivalent to 2-AG elevation. MAGL inhibitors may help treat inflammatory diseases not only in brain but also in multiple peripheral tissues through the dual EC activation via 2-AG elevation and decreased eicosanoid signaling through AA reduction.

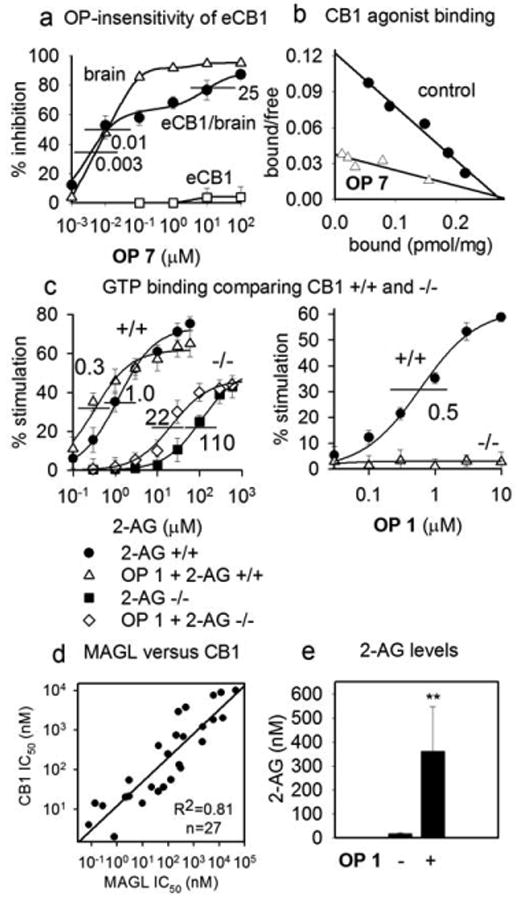

It was very surprising to find that many OPs are potent inhibitors of CB1 agonist binding in brain membranes. One possible mechanism is direct OP binding or phosphorylation of CB1 at the agonist or an allosteric site and another is indirect by OP inhibition of MAGL or FAAH to elevate the levels of 2-AG or AEA or both which then serve as the inhibitor. Three lines of evidence suggest that the OPs do not react directly with CB1. Agonist binding is OP sensitive in brain membranes but not in recombinant expressed CB1 (eCB1)14,15 (Fig. 3a) indicating that some factor other than or in addition to CB1 is required. Covalently-derivatized CB1 is not observed in brain membrane preparations labeled with a biotinylated fluorophosphonate probe under conditions in which phosphorylated MAGL and FAAH are readily evident.4 Inhibition by OP derivatization is expected to be essentially irreversible and noncompetitive with the agonist whereas inhibition by OP 7 gives an apparent competitive Scatchard plot (Fig. 3b; Supplementary data).16

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of OP action on brain CB1. (a) OP 7 displaces [3H]CP55940 agonist binding in mouse brain membranes but not in CB1 overexpressed in HEK293 cells (eCB1). The eCB1/brain curve used a mixture of 100 μg eCB1 and 100 μg brain membranes. IC50 values (μM) refer to brain (0.01) or components of eCB1/brain (0.003 and 25). (b) Scatchard plot for apparent competitive OP 7 (100 nM) displacement of [3H]CP55940 agonist binding. (c) Stimulation of GTP binding by 2-AG, 2-AG plus OP 1 (150 nM), or OP 1 alone comparing CB1 +/+ and −/− mouse brain membranes. (d) Similar OP sensitivity and specificity profiles for MAGL and CB1. (e) OP 1 (10 mg/kg ip, 4h) significantly elevated brain membrane 2-AG levels. Values are mean ± S.D., n=3-6. Significance expressed as ** p=0.01.

An alternative hypothesis is that the OP inhibits MAGL and/or FAAH and elevates the 2-AG and/or AEA level which in turn blocks agonist binding (Schemes 1 and 3). CB1, assayed as agonist binding with [3H]CP55940, is highly sensitive to many OPs (Table 1; Figs. 3a and 3b; Supplementary data) and OP 1 potentiates the CB1 agonist action of 2-AG in vitro (measured by GTPγS binding) (Fig. 3c).17 OP 1 stimulates GTPγS binding at much higher concentration (EC50 0.5 μM) (similar to the 0.3 μM EC50 of 2-AG for CB1)17 than that required to displace agonist binding (IC50 2 nM) (Table 1) in similar preparations of brain membranes. The choice between MAGL/2-AG or FAAH/AEA as the target can be approached by OP sensitivity and specificity considerations and by analysis for OP-induced elevations of EC levels. The OP sensitivity and specificity profiles correlate better for MAGL versus CB1 (r2=0.81, n=27) (Fig. 3d) than for FAAH versus CB1 (r2=0.68, n=16) (Supplementary data). Although AEA has higher CB1 affinity than 2-AG18, the ∼1000-fold greater level of 2-AG may override the affinity difference. Importantly, there is sufficient accumulation of 2-AG on OP treatment to strongly inhibit the CB1 site (Fig. 3e).19 These results support lipid rafts20 as an important compartment for 2-AG in its interactions with CB1 and MAGL. The weight of evidence favors OP action on CB1 initiated by MAGL inhibition rather than FAAH inhibition or direct on the receptor.

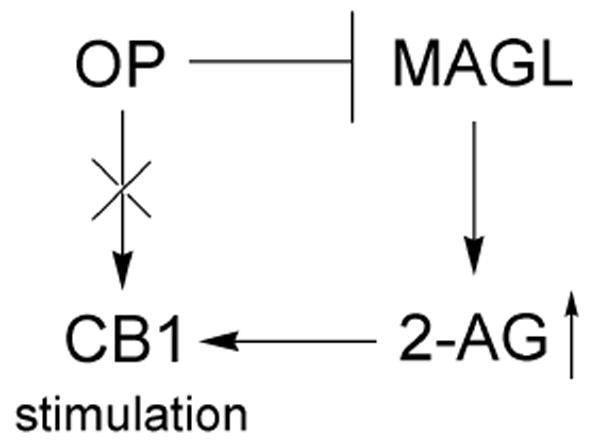

Scheme 3.

Several lines of evidence are presented for indirect OP inhibition of CB1 agonist binding in brain membranes by inhibiting MAGL to elevate 2-AG that binds CB1 rather than direct binding or phosphorylation of CB1.

In conclusion, we report the discovery of several OP MAGL inhibitors with unprecedented in vitro potency (IC50 <1 nM), a subset of which is effective in vivo in dramatically raising brain 2-AG levels leading to cannabinoid behavior. These inhibitors are attractive probes to uncover specific functions of MAGL and 2-AG in EC signaling in vivo both centrally and peripherally and to investigate MAGL as a therapeutic target. The findings establish that MAGL and 2-AG, and not phospholipases and phospholipids, regulate brain levels of free AA in multiple tissues. Finally, we propose a mechanism for OPs and other MAGL inhibitors to indirectly displace exogenous CB1 agonist binding in which elevated 2-AG levels, metabolically-stabilized in brain membranes by MAGL inhibition, serve as the actual inhibitor.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant ES008762 (J.E.C.) and DA003672 (A.H.L., grant to Billy R. Martin) from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California Toxic Substances Research & Teaching Program (D.K.N.). We thank Laura J. Sim-Selley and Dana E. Selley of Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA) for assistance with experimental design and data analysis of the GTP binding experiments. We acknowledge our University of California, Berkeley colleagues Rita Nichiporuk and Ulla Andersen for advice in the mass spectrometry studies. Dedicated to Benjamin Cravatt for exciting collaborative research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Piomelli D. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Di Marzo V, Petrosino S. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:129. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32803dbdec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ahn K, McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1687. doi: 10.1021/cr0782067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blankman JL, Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1347. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2001;98:9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quistad GB, Klintenberg R, Caboni P, Liang SN, Casida JE. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;211:78. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nomura DK, Blankman JL, Simon GM, Fujioka K, Issa RS, Ward AM, Cravatt BF, Casida JE. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:373. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segall Y, Quistad GB, Sparks SE, Nomura DK, Casida JE. Toxicol Sci. 2003;76:131. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin BR, Beletskaya I, Patrick G, Jefferson R, Winckler R, Deutsch DG, Di Marzo V, Dasse O, Mahadevan A, Razdan RK. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.In a representative reaction, ethyl n-dodecylchlorophosphonate Björkling F, Dahl A, Patkar S, Zundel M. Bioorg Med Chem. 1994;2:697–705. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(94)85020-8. (0.63 mmol) in methylene chloride (4 ml) was added to 4-cyanophenol (0.46 mmol) and triethylamine (100 μl) in methylene chloride (2 ml). The mixture was stirred 20 h at room temperature, diluted with ethyl acetate (20 ml), filtered through silica gel, and purified on a silica gel column using 30% ethyl acetate/hexanes as effluent to give OP 4 (0.38 mmol, 83%). Analogous procedures were used for 12 other O-aryl alkylphosphonates (Supplementary Table 1)

- 8.MAGL activity was determined with either unlabeled 2-AG or [14C]1-oleoylglycerol, FAAH activity with [3H]anandamide and CB1 agonist binding with [3H]CP55940 as described previously3,4. The same IC50 value (0.07 μM) was found for OP 4 in assays with 2-AG and [14C]1-oleoylglyerol (Supplementary data).

- 9.Quistad GB, Liang SN, Fisher KJ, Nomura DK, Casida JE. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:166. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalepsy bar test was performed as previously described.4

- 11.(a) Kunos G, Osei-Hyiaman D. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1101. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00057.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Nat Rev Immun. 2008;8:349. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cipollone F, Cicolini G, Bucci M. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:161. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang D, DuBois RN. Cancer Lett. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.2-AG hydrolase activity and 2-AG and AA levels were determined as described previously.4

- 13.Rosenberger TA, Villacreses NE, Contreras MA, Bonventre JV, Rapoport SI. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:109. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200298-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Farooqui T. J Neurochem. 2007;101:577. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abood ME, Ditto KE, Noel MA, Showalter VM, Tao Q. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.eCB1 overexpressed in HEK293 cells is not sensitive to OP 1 or OP 7 (up to 100,000 nM) although it displays appropriate [3H]CP55940 binding and sensitivity to WIN55212-2. Upon addition of brain membranes to eCB1, OP 7-sensitivity was partially restored.

- 16.Kinetic experiments were performed as binding isotherms for OP 7 displacement of [3H]CP55940 agonist binding (See Supplementary data). Kd (nM) 0.86 for control and 2.0 for OP 7. Bmax (pmol/mg) 0.27 for control and 0.26 for OP 7.

- 17.Guanosine-5-O-(γ-thio)-triphosphate (GTPγS) binding was determined as previously described.4 Stimulation of GTPγS binding by 2-AG is potentiated by preincubation with OP 1 (150 nM) shifting the EC50 of 2-AG from 1.0 μM to 0.3 μM. Interestingly, there is significant 2-AG-mediated stimulation of GTP binding in CB1 -/- mouse brain, also potentiated by OP 1, indicating the possible existence of another cannabinoid receptor. OP 1 alone at higher concentrations stimulates GTPγS binding in CB1 +/+ membranes (EC50 0.5 μM) but not CB1 -/- membranes, suggesting a possible direct stimulatory action of OP 1 on CB1, but not the other 2-AG-responsive receptor. This concentration is greater than 600-fold higher than the IC50 of MAGL and ∼250-fold higher than the IC50 of CB1 agonist binding.

- 18.Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K, Yamashita A, Waku K. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1995;215:89. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upon consideration of the 2-AG concentration in a typical CB1 binding assay, controls would have 16 nM compared to 360 nM in brain membranes from OP 1-treated mice, consistent with the 2-AG levels required to induce stimulation of GTP binding.

- 20.Dainese E, Oddi S, Bari M, Maccarrone M. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2702. doi: 10.2174/092986707782023235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: