Abstract

Parents often conflict over how much care to provide to their offspring. This conflict is expected to produce a negative relationship between male and female parental care, the strength of which may be mediated by both ecological and life-history variables. Previous studies have observed such trade-offs, but it is not known how generally they occur. Traditional views of sexual conflict place great importance on ecological factors in determining levels of parental care, whereas alternative views propose that the key determinant is mating opportunity. We carried out a broad-scale comparative study of parental conflict using 193 species from 41 families of birds. Using phylogenetic comparative analysis, we establish the generality of intersexual parental care conflict. We also show that parental conflict, as indicated by the disparity in care between the male and the female, depends on offspring development and mating opportunities, since in precocial species both males and females responded to increased mating opportunities. Altricial birds, however, failed to show these relationships. We also found little influence of breeding climate on parental conflict. Taken together, our results suggest that sexual conflict is a key element in the evolution of parental care systems. They also support the view that the major correlates of the intersexual conflict are mating opportunities for both sexes, rather than the breeding environment.

Keywords: sexual conflict, birds, parental care, developmental mode, breeding environment

1. Introduction

Parents provide care to promote the survival and future fitness of their offspring. However, males and females often have differing evolutionary interests with respect to reproduction (Trivers 1972; Parker 1979; Chapman et al. 2003; Arnqvist & Rowe 2005). While they share the benefits of care provisioning (i.e. fitness benefits of producing offspring), each parent pays a cost individually, since care requires time and energy and it reduces parental survival and opportunities for polygamy (Lessells 1999; Balshine et al. 2002). Therefore, each parent prefers the other to provide more care (Houston et al. 2005). This conflict of interest is expected to lead to an evolutionary tug-of-war between males and females over the provision of care (Lessells 1999; Houston et al. 2005), resulting in a negative relationship between contemporary levels of care provided by the male and the female (Houston & Davies 1985; Arnqvist & Rowe 2005; Thomas et al. 2007). Determining what mediates parental conflict is an important step in our understanding of the evolution of both parental care and mating strategies (Reynolds 1996; Székely et al. 2000).

Sexual conflict over parental care has been studied in a number of animal taxa, including both invertebrates and vertebrates (Smiseth & Moore 2004; Hinde 2006; Steinegger & Taborsky 2007; Szentirmai et al. 2007). In this paper, we focus on factors influencing the conflict between male and female care in birds, which are an excellent model system for studying hypotheses related to parental care and mating systems. Birds show a wide range of breeding systems, and their ecology, behaviour and life history are exceptionally well studied in nature (Ligon 1999; Bennett & Owens 2002). In addition, methods are available to test evolutionary hypotheses using the phylogenetic comparative approach (Harvey & Pagel 1991).

One of the most important factors influencing the strength of the conflict between males and females is the level of care required by the offspring (Silver et al. 1985; Starck & Ricklefs 1998). The required duration and intensity of care varies with the developmental mode of the offspring (Lack 1968; King 1974; Bennett & Owens 2002), with altricial young (i.e. nest-bound, naked or downy) being more demanding of time and energy than precocial (i.e. mobile and downy) young. Therefore, one may predict that in altricial species parents should cooperate to rear their young, whereas in precocial species either parent may terminate care and seek new mates. Therefore, the prediction is that sexual conflict should be more intense in precocial than in altricial species (Orians 1969; Temrin & Tullberg 1995). Hence, chick development should affect not only overall levels of care but also the extent to which care is traded off between the sexes.

Ambient and social environments are also expected to modulate parental conflict. Brood-rearing environment, especially ambient temperature, is expected to affect parental cooperation. For instance, in cold environments, both parents may be needed to continuously incubate the eggs and brood the young, whereas in milder climates one parent may be sufficient to supply incubation and brooding. It has been hypothesized that the spatial or temporal availability of resources or mates may dictate to what degree individuals can engage in polygamy, and that this in turn influences parental care levels (Verner & Willson 1966; Orians 1969; Emlen & Oring 1977; Arnold & Duvall 1994; Andersson 2004). This view predicts that there should be a close relationship between ecology, the ambient environment and mating opportunities, and in turn between mating opportunities and levels of parental care. Thus, there should exist a link between ecological factors influencing resource availability and parental care.

Parental care may also be influenced by mating opportunities as hypothesized by game-theoretic models (Balshine-Earn & Earn 1998; McNamara et al. 2000; Barta et al. 2002) and as shown by experiments (Keenleyside & Mackereth 1992; Ahnesjö 1995, Balshine-Earn 1997). These studies predict that if a parent has a high chance of remating and renesting, then it should capitalize from this opportunity and desert, given that its mate is willing to continue raising the young until the young are independent (Székely et al. 1996). Therefore, across bird species, we may expect to see increased conflict when one sex (the male or the female) has a high remating opportunity.

Here, we use data from 193 avian species, comprising 12 orders and 41 families, to examine the effects of chick developmental mode, breeding climate and mating opportunities on patterns of parental care (see electronic supplementary material). Specifically, we use phylogenetic comparative methods to test for an effect of chick developmental mode on both the overall level of care and the intensity of sexual conflict (as measured by the slope and strength of the correlation between male and female care). We also test the relative influences of ecological conditions (via climate) and mating opportunities on patterns of parental care, paying special attention to the relative strength of interaction effects between climate, parental care and mating opportunities.

2. Material and methods

(a) Data collection

We used an existing dataset (Liker & Székely 2005) on the parental care and mating opportunities of 193 species of birds (Monroe & Sibley 1993). These high-resolution data, gathered from reference books, family- and species-level monographs and published literature, provided the starting point for our study. The level of care was scored separately for males and females by dividing the breeding cycle into five activities: nest building; incubation; brooding; chick feeding; and chick defence.

To generate the care score, first, each activity was given a score of 0 or 1 for each sex, depending on whether or not each sex contributed to that aspect of care. This allowed the total care provided to be measured on a five-point scale. Next, we weighted these scores by the relative contribution each sex provides at each point. Each part of the breeding cycle was re-scored out of three points for each sex, according to how much each one contributed to that aspect of care. If a given sex did participate, then a score of 1 (1–33% of care), 2 (34–66% of care), 3 (67–99% of care) or 4 (100% of care) was assigned. The maximum potential score for each sex was thus 20 points, with the maximum total for each species also being 20 points. We finally calculated the disparity in care (male score−female score) for each sex in order to measure the degree to which one or the other provided the bulk of the care.

To augment these data, we scored the developmental mode of each species as being altricial (nest-bound at hatching, naked or downy) or precocial (mobile at hatching, downy). This classification is consistent with that of other studies (e.g. Temrin & Tullberg 1995). As an estimate of breeding climate, we used breeding range maps collated for use in a larger analysis of biodiversity patterns (Orme et al. 2005) to calculate the percentage of the total latitudinal range found in the tropical or subtropical (0–30°), temperate (30–60°) or polar (60–90°) climatic zones. We use breeding latitude as a climate surrogate: it is generally considered a good indicator of broad climatic conditions, in that at high latitudes, the productive season is short and many species (particularly birds) must migrate to more favourable regions outside of the breeding season, whereas at lower latitudes, at a given elevation, the productive season tends to be longer and other aspects of the climate are more favourable to year-round residency. Climate, as indicated by breeding latitude, can thus be considered a good proxy of ecological opportunity for reproduction. Using the percentages estimated, we then assigned each species to a main breeding climate by selecting the one in which the largest percentage of the breeding range occurred.

We use polygamy as a proxy for mating opportunities. For each species, the percentage of individuals exhibiting polygamy was recorded for each sex separately (see Liker & Székely 2005). If a sex exhibited both sequential and simultaneous polygamy, then these two values were summed to provide a percentage of total polygamy for that sex. If several estimates of polygamy were available for a sex, then the mean was used. To express the overall incidence of polygamy for each sex, a score from 0 to 4 was assigned, with ‘0’ indicating effectively no polygamy (less than 0.1% of individuals), ‘1’ indicating rare polygamy (0.1–1%), ‘2’ indicating uncommon polygamy (1–5%), ‘3’ indicating moderate polygamy (5–20%) and ‘4’ indicating common polygamy (greater than 20%). Scoring was necessary, because for several species only verbal (rather than percentage) descriptions of levels of polygamy were available (see justification in Liker & Székely (2005)).

(b) Statistical analysis

In this study, we aimed to address two issues. First, we wanted to know whether there was a general relationship between levels of male and female care across a broad range of bird species. Second, we wanted to assess the relative importance of developmental mode, breeding climate and levels of mating opportunity in determining patterns of parental care. We therefore developed two models. To test for a general relationship between male and female care, the first model included male care as the dependent variable and female care as the independent one. To test for the relative influences of developmental mode, ecology and mating opportunities, the second model included the disparity between male and female care as the dependent variable, mating opportunities for the males and females as continuous independent variables and developmental mode and breeding climate as fixed factors. The two-way interactions between developmental mode and each of the parental care and mating opportunity variables, and between breeding climate and each of the variables, were included in models. These interaction terms informed us about the influence of each factor on the magnitude of the dependent variable, and also the influence on the slope of relationships between parental care and mating opportunity across factor levels.

To control for phylogeny, we used phylogenetic generalized least-squares modelling (Martins & Hansen 1997; Pagel 1999; code available from R.P.F. on request) and phylogenetic manipulations in the APE package (Paradis et al. 2004) written for the R statistical application (R Core Development Team 2006). Our phylogeny was a composite tree using Sibley & Ahlquist's (1990) arrangement of orders and families, and additional phylogenetic information from other studies for those genera and species not included in their phylogeny (for full details, see Liker & Székely (2005)). All results and statistics quoted in §3 have been corrected for phylogenetic dependence (Pagel 1999; Freckleton et al. 2002).

3. Results

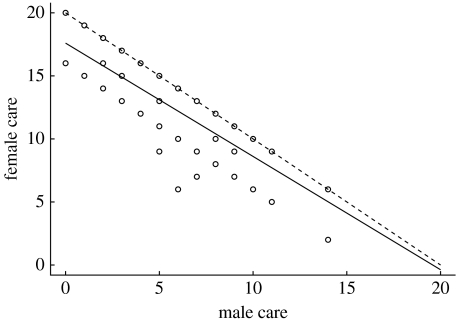

Male and female parental care were negatively correlated (figure 1; F1,192=83.93, p<0.0001). This correlation is mediated mainly through variance across species in the level of male care: the variance in male care was significantly higher than that of female care (variance ratio test, corrected for phylogeny: F192,192=1.349; p<0.02). Moreover, the total care provided by both parents combined correlated more strongly with male care (r=0.612; n=193; p<0.0001) than with female care (r=0.260; n=193; p<0.001), with the main reason for this being that males regularly do not contribute to certain aspects of care.

Figure 1.

Relationship between levels of male and female parental care in birds. The solid line showing the regression (female care=14,97−0.74 male care; F1,191=387, p<0.0001) has been adjusted for phylogenetic relationships among species. Each data point represents a species. The maximum combined score for both sexes is 20 and the dashed line shows the line of y=20−x, i.e. where a change in care by one sex is compensated for exactly by a change in care by the other.

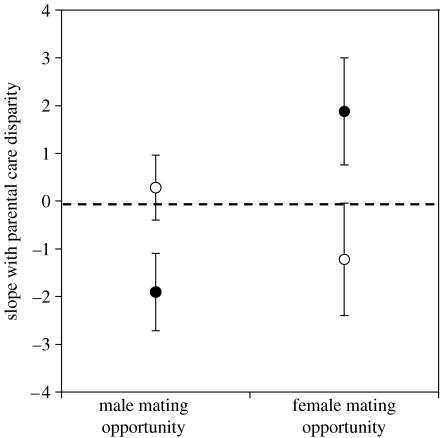

What determines the extent to which males provide care? Parental care disparity was strongly linked to mating opportunities for both males and females, and these relationships were different between altricial and precocial species, as indicated by the significant interaction terms between male mating opportunity and developmental mode, and female mating opportunity and developmental mode (table 1).

Table 1.

The influences of chick developmental mode, breeding climate and mating opportunities on male–female parental care disparity (response variable, see §2) in birds. (Phylogenetic generalized least-squares model, using 193 avian species (see electronic supplementary material). Effects were tested sequentially. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.)

| source | d.f.a | SSa | MSa | Fa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| male mating opportunity (MMO) | 1 | 92.7 | 92.7 | 51.2*** |

| female mating opportunity (FMO) | 1 | 46.7 | 46.7 | 25.8*** |

| developmental mode (D) | 1 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 1.16 |

| breeding climate (C) | 2 | 8.92 | 4.46 | 2.46 |

| MMO×D | 1 | 47.9 | 47.9 | 26.4*** |

| MMO×C | 2 | 18.7 | 9.38 | 5.18** |

| FMO×D | 1 | 95.0 | 95.0 | 52.4*** |

| FMO×C | 2 | 1.44 | 0.72 | 0.39 |

| error | 181 | 327.9 | 1.181 |

Statistical values from PGLS ANOVA: d.f., degrees of freedom; SS, sum of squares; MS, mean square; F, F-value.

Examination of the nature of the relationships between parental care disparity and mating opportunity among altricial versus precocial species shows where the differences between developmental mode groups lie (figure 2). In precocial species, both males and females respond to increased mating opportunities as predicted (figure 2): as male mating opportunities increase, males reduce their parental duties relative to females. Similarly, as female mating opportunities increased, females reduce their contribution to care relative to males. However, in altricial species, there was no relationship between parental care disparity and male mating opportunity, but a significant (albeit weak) negative relationship between parental care disparity and female mating opportunity (figure 2). In other words, in altricial species, there is some evidence that male mating opportunities have no influence on male care provisioning, while, as female mating opportunities increased, the parental care disparity became somewhat more female-biased.

Figure 2.

Comparison of altricial (open circles) and precocial (filled circles) species with respect to the relationship between parental care disparity (i.e. male minus female care levels) and mating opportunities for each sex (see §2 for further explanations). Error bars are 95% confidence limits around slopes.

With respect to breeding climate, we found only an indirect effect on parental care disparity via an interaction between parental care disparity, male mating opportunity and climate (table 1). Otherwise, there were no effects of climate.

4. Discussion

(a) Potential for sexual conflict in birds

In our analyses, male and female parental care were negatively correlated across a broad range of bird taxa. This indicates that there is an evolutionary tug-of-war between males and females over the provisioning of care, a result consistent with the prediction of sexual conflict theory. Reynolds & Székely (1997) and Thomas & Székely (2005) reported similar results for shorebirds. Our work, however, using parental care data from a range of taxa further implicates selection on male care as the driver of the tug-of-war, and that the trade-off in care is modulated by offspring development and mating opportunities for both the male and the female, but not strongly by breeding climate.

The regression slope indicates a less than compensatory increase in female care per unit increase in male care (figure 1). Moreover, there is more variance in male care than female care, with the total care responding more closely to the amount of male care provided. This difference has been predicted in previous literature (Trivers 1972; Clutton-Brock 1991; Queller 1997), but has not been demonstrated in birds. This is somehow surprising, because in birds (unlike mammals), either sex seems capable of providing all essential elements of care, including incubation and feeding the young. The key additional result from our analyses is that total care is more closely correlated with male care, so that selection for increased total care appears to be mainly accommodated by increasing the amount of male care. Equivalently, selection on males for a reduced contribution to care leads to a reduction in the overall level of care, even though females respond by provisioning more.

Variation in male care may be related to a number of traits, including confidence of paternity. We did not include this aspect of avian life history in our study, but it would be of interest to include it in future work. We hypothesize that in precocial species, matings are played out in the open: one parent may desert anyway, so individuals are free to seek alternative mates. In altricial species, however, parents may be under stronger selection to rear their young together. They cannot increase their reproductive success by deserting, and so sneaky copulations remain a viable option for both males and females. Males can therefore deal with selective factors such as good genes, offspring genetic diversity and inbreeding avoidance through either simultaneous or sequential polygamy, depending on (among other things) the developmental mode of their young. Similarly, females from precocial species can also deal with them through sequential matings, but altricial females may need to try to achieve all of these within one or at most only a few broods.

(b) Influences of developmental mode, breeding climate and mating system

We found strong influences of both male and female mating opportunities, but not of breeding climate, on patterns of parental care disparity. These results suggest that ecology, at least at the level we measured, plays little or no role in determining levels of care. It remains to be seen, however, whether other ecological factors contribute to the overall patterns we observed. Certainly, there are other aspects of ecology that could be examined using a similar approach to that we adopt here, such as habitats (Verner & Willson 1966), resource availability (Orians 1969; Emlen & Oring 1977; Ahnesjö et al. 2001), selection on offspring survival by predators and conspecifics (Kosztolányi et al. 2006) or specific environmental variables such as temperature (Ahnesjö 1995). For example, in shorebirds, there was a correlation between length of breeding season and levels of polygamy (Andersson 2004; Thomas & Székely 2005). The results from these analyses suggest that ecology may play a role in determining the outcome of the level of care provided by each sex within some taxa, even though our study suggested that this role either may not be apparent as a general rule or is true for some ecological variables and not others.

In addition, our analysis reveals that the developmental mode of the chicks has a strong influence on the relationship between parental care and mating opportunities. In altricial species, males appear not to take into account their level of care relative to that of the female when making decisions regarding additional mating opportunities, while in precocial species, males trade off care and polygyny. Interestingly, females were also responsive to mating opportunities: in altricial species, females take on relatively more of the parental care with increased female mating opportunities, while in precocial species, females take on relatively less. Taken together, the sexes appear to play the same strategies, at least in birds: if their young need little care, then both males and females respond to enhanced mating opportunities.

A number of factors may be important in determining why these differences between developmental mode groups, and between males and females within a group, occur. Males and females of both altricial and precocial species vary in the average amount of care they provide across stages of the breeding cycle, but they do not appear to do so in the same way. For example, different sexes or developmental modes can vary with respect to the stages in which they provide the most care, or the consistency of care across stages. Variability such as this has the potential to influence the relationship between parental care and polygamy by limiting when an individual can seek mating opportunities (Ketterson & Nolan 1994; Schwegmeyer et al. 1999). These limitations on the timing of mating opportunities can in turn influence the type of polygamy in which an individual engages (i.e. simultaneous or sequential), leading to variation in the degree to which each sex or developmental mode group is simultaneously versus sequentially polygamous.

Following on from this, simultaneous and sequential polygamy can differ with respect to male certainty of paternity, in that we expect certainty to be higher where females are sequentially polygamous than where either sex is simultaneously polygamous (Valle 1994; Fishman & Stone 2006). Where males are uncertain of the paternity of the offspring of the social mate, reduced care is often the result, particularly with respect to the feeding of their young (Møller & Birkhead 1993; Whittingham & Dunn 1998; Fishman & Stone 2004; but see Whittingham & Lifjeld 1995; Yezerinac et al. 1996). So, if females of altricial and precocial species differ with respect to when they are most able to remate, this may explain why, in altricial species, female care increases with levels of polyandry, while the opposite occurs in precocial species (Albrecht et al. 2006).

Parental care and its relationship with polygamy may also influence, or be influenced by, the strength of sexual selection. Sexual conflict may therefore constitute primarily a feedback relationship between parental care and mating opportunities, and patterns of both parental care and polygamy depend only weakly, if at all, on ecological factors (Arnqvist & Rowe 2005). This latter theory allows for only a weak direct effect of ecological factors on parental care, for example, if species breeding where the productive season is short or unpredictable need to provide more care than those breeding where the season is longer or less seasonal (King 1974; Andersson 2004). Recent studies have highlighted the possibility of such feedback relationships (Alonzo & Warner 2000; Székely et al. 2000; Andersson 2004; Alonzo in press).

For example, sexual conflict can create selection for choice based on perceived ability to provide high-quality parental care (Andersson 1994; Westneat & Sargent 1996). Sexual selection has also been shown to correlate with the pattern and occurrence of alternative reproductive tactics (Alonzo & Warner 2000) and with levels of parental investment (Arnold & Duvall 1994). Alternatively, the time of the greatest mating opportunity may differ between males and females, or between species with differing developmental modes, resulting in variation in the operational sex ratio over the duration of the breeding cycle (Andersson 1994), and hence opportunities for mating.

Finally, there may be population-level factors contributing to the overall patterns we observed. These may include any attribute that affects the time and energy budgets of individuals (King 1974), including, for example, breeding density or degree of breeding synchrony (Schwegmeyer & Ketterson 1999; Poirier et al. 2004).

In conclusion, we identified two important components of parental conflict in birds: mating opportunities and chick development. We envisage several ways of advancing parental conflict research. First, we used a single parental care score for the entire breeding period, and it may be that intersexual differences, or differences between altricial and precocial species, are influenced strongly by some stages of the breeding cycle, but not others. Future work may therefore need to focus on particular aspects of the breeding cycle. Second, we combined both sequential and simultaneous polygamy in our study, and it may be important in future studies to examine each form separately, as the implications of each for male–female differences in genetic interest in offspring, and for sexual selection, may differ between them. Finally, other aspects of both the breeding environment and density-dependent population processes may be important factors to consider in studies looking at variation in parental care.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NERC (NE/C004167/1). We thank Gavin Thomas, Tom Webb and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. R.P.F. is a Royal Society University Research fellow. T.S. is a Hrdy visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2007.1395 or via http://journals.royalsociety.org.

Supplementary Material

Data and their references used in Olson et al. The strength of parental conflict in birds: testing the roles of offspring development, ecology, and mating opportunities

References

- Ahnesjö I. Temperature affects male and female potential reproductive rates differently in the sex-role reversed pipefish, Syngnathus typhle. Behav. Ecol. 1995;6:229–233. doi:10.1093/beheco/6.2.229 [Google Scholar]

- Ahnesjö I, Kvarnemo C, Merilaita S. Using potential reproductive rates to predict mating competition among individuals qualified to mate. Behav. Ecol. 2001;12:397–401. doi:10.1093/beheco/12.4.397 [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht T, Kreisinger J, Pialek J. The strength of direct selection against female promiscuity is associated with rates of extra-pair fertilizations in social monogamous songbirds. Am. Nat. 2006;167:739–744. doi: 10.1086/502633. doi:10.1086/502633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo, S. H. In press. Conflict between the sexes and alternative reproductive tactics within a sex. In Alternative reproductive tactics (eds R. F. Oliveira, M. Taborsky & J. Brockmann). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Alonzo S.H, Warner R.R. Female choice, conflict between the sexes and the evolution of male alternative reproductive behaviours. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2000;2:149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1994. Sexual selection. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M. Social polyandry, parental investment, sexual selection, and evolution of reduced female gamete size. Evolution. 2004;58:24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold S.J, Duvall D. Animal mating systems: a synthesis based on selection theory. Am. Nat. 1994;143:317–348. doi:10.1086/285606 [Google Scholar]

- Arnqvist G, Rowe L. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2005. Sexual conflict. [Google Scholar]

- Balshine S, Kempenaers B, Székely T. Conflict and cooperation in parental care: introduction. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2002;357:237–240. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0933. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balshine-Earn S. The benefits of uniparental care versus biparental mouth brooding in Galilee St. Peter's fish. J. Fish Biol. 1997;50:371–381. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01365.x [Google Scholar]

- Balshine-Earn S, Earn D.J.D. On the evolutionary pathway of parental care in mouth brooding cichlid fishes. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:2217–2222. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0562 [Google Scholar]

- Barta Z, Houston A.I, McNamara J.M, Sze´kely T. Sexual conflict about parental care: the role of reserves. Am. Nat. 2002;159:687–705. doi: 10.1086/339995. doi:10.1086/339995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett P.M, Owens I.P.F. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. Evolutionary ecology of birds: life histories, mating systems, and extinction. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman T, Arnqvist G, Bangham J, Rowe L. Sexual conflict. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003;18:41–46. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)00004-6 [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T.H. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1991. The evolution of parental care. [Google Scholar]

- Emlen S.T, Oring L.W. Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science. 1977;197:215–223. doi: 10.1126/science.327542. doi:10.1126/science.327542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman M.A, Stone L. Indiscriminate polyandry and male parental effort. Bull. Math. Biol. 2004;66:47–63. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8240(03)00066-1. doi:10.1016/S0092-8240(03)00066-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman M.A, Stone L. Trade-up polygyny and breeding synchrony in avian populations. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;238:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.012. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freckleton R.P, Harvey P.H, Pagel M. Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: a test and review of evidence. Am. Nat. 2002;160:712–726. doi: 10.1086/343873. doi:10.1086/343873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P.H, Pagel M.D. The comparative method in evolutionary biology. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hinde C.A. Negotiation over offspring care?—A positive response to partner-provisioning rate in great tits. Behav. Ecol. 2006;17:6–12. doi:10.1093/beheco/ari092 [Google Scholar]

- Houston A.I, Davies N.B. The evolution of cooperation and life history in the dunnock Prunella modularis. In: Sibly R.M, Smith R.H, editors. Behavioural ecology: ecological consequences of adaptive behaviour. Blackwell Science; Oxford, UK: 1985. pp. 471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Houston A.I, Székely T, McNamara J.M. Conflict between parents over care. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.008. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenleyside M.H.A, Mackereth R.W. Effects of loss of male parent on brood survival in a biparental cichlid fish. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1992;34:207–212. doi:10.1007/BF00002396 [Google Scholar]

- Ketterson E.D, Nolan V., Jr Male parental behavior in birds. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1994;25:601–628. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.25.110194.003125 [Google Scholar]

- King J.R. Seasonal allocation of time and energy resources in birds. In: Paynter R.A Jr, editor. Avian energetics. Nuttall Ornithological Club; Cambridge, MA: 1974. pp. 4–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kosztolányi A, Székely T, Cuthill I.C, Yilmaz K.T, Berberoglu S. The influence of habitat on brood-rearing behaviour in the Kentish plover. J. Anim. Ecol. 2006;75:257–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01049.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack D. Methuen & Co., Ltd; London, UK: 1968. Ecological adaptations for breeding in birds. [Google Scholar]

- Lessells C.M. Sexual conflict in animals. In: Keller L, editor. Levels of selection in evolution. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1999. pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ligon J.D. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1999. Evolution of avian breeding systems. [Google Scholar]

- Liker A, Székely T. Mortality costs of sexual selection and parental care in natural populations of birds. Evolution. 2005;59:890–897. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01762.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins E.P, Hansen T.F. Phylogenies and the comparative method: a general approach to incorporating phylogenetic information into the analysis of interspecific data. Am. Nat. 1997;149:646–667. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J.M, Székely T, Webb J.N, Houston A.I. A dynamic game-theoretic model of parental care. J. Theor. Biol. 2000;205:605–623. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2093. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2000.2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller A.P, Birkhead T.R. Certainty of paternity covaries with paternal care in birds. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1993;33:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe B.L, Sibley C.G. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1993. A world checklist of birds. [Google Scholar]

- Orians G.H. On the evolution of mating systems in birds and mammals. Am. Nat. 1969;103:589–603. doi:10.1086/282628 [Google Scholar]

- Orme C.D.L, et al. Global hotspots of species richness are not congruent with endemism or threat. Nature. 2005;436:1016–1019. doi: 10.1038/nature03850. doi:10.1038/nature03850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel M.D. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature. 1999;401:877–884. doi: 10.1038/44766. doi:10.1038/44766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G.A. Sexual selection and sexual conflict. In: Blum M.S, Blum N.A, editors. Sexual selection and reproductive competition in insects. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1979. pp. 123–166. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier N.E, Whittingham L.A, Dunn P.O. Males achieve greater reproductive success through multiple broods than through extrapair mating in house wrens. Anim. Behav. 2004;67:1109–1116. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.06.020 [Google Scholar]

- Queller D.C. Why do females care more than males? Proc. R. Soc. B. 1997;264:1555–1557. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0216 [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J.D. Animal breeding systems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996;11:68–72. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)81045-7. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)81045-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J.D, Székely T. The evolution of parental care in shorebirds: life-histories, ecology and sexual selection. Behav. Ecol. 1997;8:126–134. doi:10.1093/beheco/8.2.126 [Google Scholar]

- Schwegmeyer P.L, Ketterson E.D. Breeding synchrony and EPF rates: the key to a can of worms? Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999;14:47–48. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01541-9. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01541-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwegmeyer P.L, St Clair R.C, Moodie J.D, Lamey T.C, Schnell G.D, Moodie M.N. Species differences in male parental care in birds: a reexamination of correlates with paternity. Auk. 1999;116:487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley C.G, Ahlquist J.E. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1990. Phylogeny and classification of birds: a study in molecular evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Silver R, Andrews H, Ball G.F. Parental care in an ecological perspective: a quantitative analysis of avian subfamilies. Integr. Comp. Biol. 1985;25:823–840. doi:10.1093/icb/25.3.823 [Google Scholar]

- Smiseth P.T, Moore A.J. Behavioral dynamics between caring males and females in a beetle with facultative biparental care. Behav. Ecol. 2004;15:621–628. doi:10.1093/beheco/arh053 [Google Scholar]

- Starck J.M, Ricklefs R.E. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. Avian growth and development: evolution within the altricial–precocial spectrum. [Google Scholar]

- Steinegger M, Taborsky B. Asymmetrical sexual conflict over parental care in a biparental cichlid. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007;61:933–941. doi:10.1007/s00265-006-0322-x [Google Scholar]

- Székely T, Webb J.N, Houston A.I, McNamara J.M. An evolutionary approach to offspring desertion in birds. In: Nolan V Jr, Ketterson E.D, editors. Current ornithology. vol. 13. Plenum Publisher; New York, NY: 1996. pp. 271–330. ch. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Székely T, Webb J.N, Cuthill I.C. Mating patterns, sexual selection and parental care: an integral approach. In: Appolonio M, Festa-Bianchet M, Mainardi M, editors. Vertebrate mating systems. World Scientific; Singapore: 2000. pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- Szentirmai I, Székely T, Komdeur J. Sexual conflict over care: antagonistic effects of clutch desertion on reproductive success of male and female penduline tits. J. Evol. Biol. 2007;20:1739–1744. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01392.x. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temrin H, Tullberg B.S. A phylogenetic analysis of the evolution of mating systems in relation to altricial and precocial young. Behav. Ecol. 1995;6:296–307. doi:10.1093/beheco/6.3.296 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G.H, Székely T. Evolutionary pathways in shorebird breeding systems: sexual conflict, parental care, and chick development. Evolution. 2005;59:2222–2230. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb00930.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G.H, Székely T, Reynolds J.D. Sexual conflict and the evolution of breeding systems in shorebirds. Adv. Study Behav. 2007;37:277–340. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R.L. Parental investment and sexual selection. In: Campbell B, editor. Sexual selection and the descent of man. Aladine; Chicago, IL: 1972. pp. 136–179. [Google Scholar]

- Valle C.A. Parental role-reversed polyandry and paternity. Auk. 1994;111:476–478. [Google Scholar]

- Verner J, Willson M.F. The influence of habitats on mating systems of North American passerine birds. Ecology. 1966;47:143–147. doi:10.2307/1935753 [Google Scholar]

- Westneat D.F, Sargent R.C. Sex and parenting: the effects of sexual conflict and parentage on parental strategies. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996;11:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)81049-4. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)81049-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham L.A, Dunn P.O. Male parental effort and paternity in a variable mating system. Anim. Behav. 1998;55:629–640. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0751. doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham L.A, Lifjeld J.T. High parental investment in unrelated young: extra-pair paternity and male parental care in house martins. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1995;37:103–108. doi:10.1007/s0026550370103 [Google Scholar]

- Yezerinac S.M, Weatherhead P.J, Boag P.T. Cuckoldry and lack of parentage-dependent paternal care in yellow warblers: a cost–benefit approach. Anim. Behav. 1996;52:821–832. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0227 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data and their references used in Olson et al. The strength of parental conflict in birds: testing the roles of offspring development, ecology, and mating opportunities