Abstract

Fatty acid desaturases are enzymes that introduce double bonds into the hydrocarbon chains of fatty acids. The fatty acid desaturases from 37 cyanobacterial genomes were identified and classified based upon their conserved histidine-rich motifs and phylogenetic analysis, which help to determine the amounts and distributions of desaturases in cyanobacterial species. The filamentous or N2-fixing cyanobacteria usually possess more types of fatty acid desaturases than that of unicellular species. The pathway of acyl-lipid desaturation for unicellular marine cyanobacteria Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus differs from that of other cyanobacteria, indicating different phylogenetic histories of the two genera from other cyanobacteria isolated from freshwater, soil, or symbiont. Strain Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421 was isolated from calcareous rock and lacks thylakoid membranes. The types and amounts of desaturases of this strain are distinct to those of other cyanobacteria, reflecting the earliest divergence of it from the cyanobacterial line. Three thermophilic unicellular strains, Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 and two Synechococcus Yellowstone species, lack highly unsaturated fatty acids in lipids and contain only one Δ9 desaturase in contrast with mesophilic strains, which is probably due to their thermic habitats. Thus, the amounts and types of fatty acid desaturases are various among different cyanobacterial species, which may result from the adaption to environments in evolution.

1. Introduction

In living organisms, the regulation of membrane fluidity is necessary for the proper function of biological membranes, which is important in the tolerance and acclimatization to environmental stresses such as heat, cold, desiccation, salinity, nitrogen starvation, photooxidation, anaerobiosis, and osmosis, and so forth. Unsaturated fatty acids are essential constituents of polar glycerolipids in biological membranes and the unsaturation level of membrane lipids is important in controlling the fluidity of membranes [1]. Fatty acid desaturases are enzymes that introduce double bonds into the hydrocarbon chains of fatty acids to produce unsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids [2], thus these enzymes play an important role during the process of environmental adaptation.

Cyanobacteria, prokaryotes capable of carrying out a plant-like oxygenic photosynthesis, represent one of the oldest known bacterial lineages, with fossil evidence suggesting an appearance around 3–3.5 billion years ago [3]. Cyanobacteria comprise over 1600 species with various morphologies and species-specific characteristics such as cell movement, cell differentiation, and nitrogen fixation [4]. Extant cyanobacteria can be found in virtually all ecosystem habitats on Earth, ranging from the freshwater lakes and rivers through to the oceans, and also in hot springs and deserts, ranging from the hottest to the cold dry valleys of Antarctica [3].

Polyunsaturated membrane lipids play important roles in the growth, respiration, and photosynthesis of cyanobacteria. It is well documented that the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids in membrane lipids of cyanobacteria can be altered by changing the temperature [5–7]. The mechanism that regulates the fatty acid desaturation of membrane lipids in response to temperature has been demonstrated to be the result of the up- or downregulation of the expression of the desaturase genes [8]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the position of double bonds in fatty acids is more influential on the fluidity of membrane lipids than the number of double bonds in fatty acids [9]. It is also found that the temperature of the phase transition dramatically decreased when the first and second double bonds are introduced into fatty acids, whereas the introduction of the third and fourth double bonds do not further lower the temperature of phase transition of membrane lipids [10].

Exposure of cyanobacteria to high PAR (photosynthetically active radiation) or UV radiation leads to photoinhibition of photosynthesis, thereby limiting the efficient fixation of light energy [11, 12]. In Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, the replacement of all polyunsaturated fatty acids by a monounsaturated fatty acid suppressed the growth of the cells at low temperature, and it decreased the tolerance of the cells to photoinhibition of photosynthesis at low temperature by suppressing recovery of the photosystem II protein complex from photoinhibitory damage. However, the replacement of tri- and tetraunsaturated fatty acids by a diunsaturated fatty acid did not have such effects. These findings indicate that polyunsaturated fatty acids are important in protecting the photosynthetic machinery from photoinhibition at low temperatures [13]. Transformation of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 with the desA gene for a Δ12 desaturase has been reported to increase the unsaturation of membrane lipids and thereby enhance the tolerance of cyanobacterium to intense light. These findings demonstrate that the ability of membrane lipids to desaturate fatty acids is important for the photosynthetic organisms to be able to tolerate high-light stress by accelerating the synthesis of the D1 protein de novo [14].

Cyanobacteria have been classified into four groups in terms of the composition of fatty acids, the distribution of fatty acids at the sn position of the glycerol moiety, and the position of double bonds in the fatty acids [15]. Strains in Group 1 (e.g., Prochlorothrix hollandica, Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301, Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942, Synechococcus elongatus, Thermosynechococcus elongates, and Thermosynechococcus vulcanus) introduce a double bond only at the Δ9 position of fatty acids at the sn-1 or sn-2 position of glycerolipids. Strains in Group 2 (e.g., Anabaena variabilis, Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002, Nostoc punctiforme, and Nostoc sp. SO-36) introduce double bonds at the Δ9, Δ12, and Δ15 (ω3) positions of C18 acids at the sn-1 position, and at the Δ9 position of C16 acids at the sn-2 position. Strains in Group 3 (e.g., Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714 and Spirulina platensis) can also introduce three double bonds, but these are at the Δ6, Δ9, and Δ12 positions of C18 acids at the sn-1 position. Strains in Group 4 (e.g., Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Tolypothrix tenuis) introduce double bonds at the Δ6, Δ9, Δ12, and Δ15 (ω3) positions of C18 acids at the sn-1 position. The C16 acids at the sn-2 position are not desaturated in Groups 3 and 4.

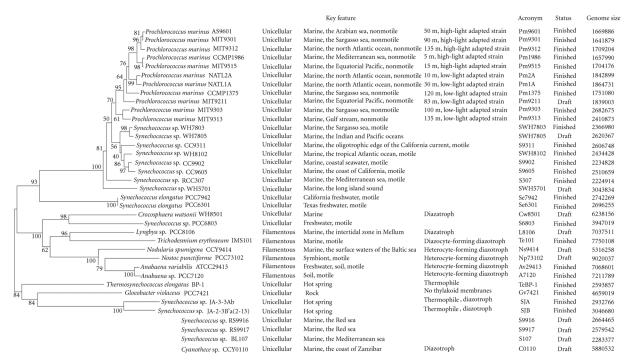

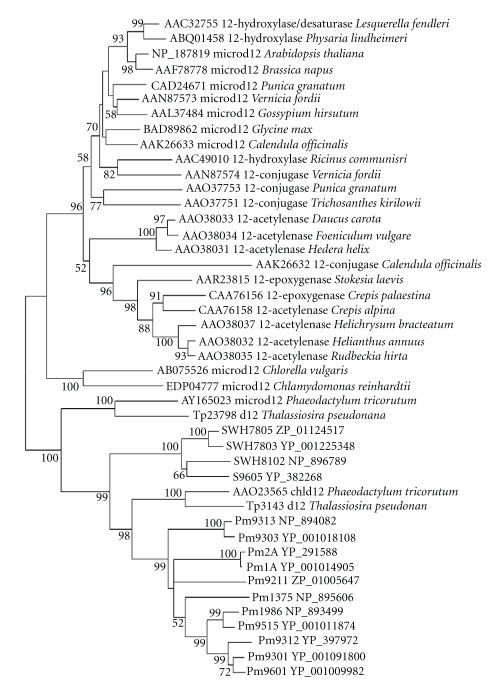

The entire genome sequence of a unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was first described in 1996 [16]. To date, 37 cyanobacterial genomes have been sequenced (Figure 1). These genomes are those of the filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, the thermophilic strain Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1, the thylakoid-free strain Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421, the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain WH8102, the Prochlorococcus marinus strains SS120, MED4, MIT 9313, Synechococcus sp. CC9311, and others. These genome-sequencing projects undoubtedly bring a great convenience to obtain a comprehensive dataset of genes involved in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. In this work, we identified all the putative fatty acid desaturases using bioinformatic tools and presented a genomic comparison of the fatty acid desaturases from 37 cyanobacterial genomes. The identification of novel desaturases and the reconstruction of the pathways for unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in cyanobacteria will guide the experimental analysis and provide clues in study of the relationship between the unsaturation level of membrane lipids and environmental adaptation in higher plants.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the sequenced cyanobacterial strains. A Neighbor-joining tree for 33 sequenced cyanobacteria constructed based on 16 S rRNA as was described in Section 2 and about 1300 positions were employed. To maximize the number of sites available for analysis, three partial sequences from Synechococcus sp. RS9917 (170 bp), Synechococcus sp. RS9916 (865 bp), and Synechococcus sp. BL107 (296 bp) were excluded. Moreover, no 16 S rRNA sequence was found in Cyanothece sp. CCY0110.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Search for Novel Fatty Acid Desaturase Genes

The genomes of 37 cyanobacteria including genera Synechocystis, Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus, Anabaena, Nostoc, Trichodesmium, Gloeobacter, Crocosphaera, Cyanothece, and Lyngbya were downloaded from IMG database (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/pub/main.cgi). The dataset comprised of well-characterized fatty acid desaturases from Synechocystis PCC 6803 (NP_442430, NP_441489, NP_441622, NP_441824), Nostoc sp. SO-36 (CAF18426), Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (AAB61353, AAF21445, AAB61352), Arthrospira platensis (CAA05166, Q54794, CAA60573), Synechococcus vulcanus (AAD00699), Synechococcus s elongatus sp. PCC 6301 (YP_172259), Synechococcus elongatus sp. PCC 7942 (YP_401578), Phaeodactylum tricorutum (AAW70158, AY082393, AAO23565, AY165023), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (AB007640, ABL09485, EDP04777), and Chlorella vulgaris (AB075526, AB075527) was used to construct a query protein set. Each protein in this query dataset was used to search the potential novel sequences in 37 cyanobacterial species with whole genome sequences available, by using the BLASTP and TBLASTN programs, with E-value < 1e − 10. The searches were repeated until no novel sequences were detected at the e value threshold used. The putative desaturase genes across 37 genomes were summarized in Table 1. The other amino acid sequences beyond the 37 cyanobacterial species were retrieved from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The accession number of these sequences and the names of corresponding cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, higher plants, fungi, and animals were indicated in Table 2.

Table 1.

Lists of putative desaturase genes from thirty seven cyanobacterial genomes.

| Species | Locus tag | Accession | DNA coordinates | Length | Proposed function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 | all4991 | NP_489031 | 5963080⋯5963937 | 857 | d9 |

| all1599 | NP_485639 | 1879629⋯1880447 | 818 | d9 | |

| all1598 | NP_485638 | 1878346⋯1879398 | 1052 | d12 | |

| all1597 | NP_485637 | 1876897⋯1877976 | 1079 | d15 | |

| alr3189 | NP_487229 | 3858986⋯3859762 | 776 | crtW | |

| alr4009 | NP_488049 | 4829483⋯4830322 | 839 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 | Ava_2277 | YP_322790 | 2832413⋯2833270 | 857 | d9 |

| Ava_4212 | YP_324706 | 5282348⋯5283166 | 818 | d9 | |

| Ava_4211 | YP_324705 | 5281066⋯5282118 | 1052 | d12 | |

| Ava_4210 | YP_324704 | 5279614⋯5280693 | 1079 | d15 | |

| Ava_2048 | YP_322565 | 2535646⋯2536410 | 764 | crtW | |

| Ava_3888 | YP_324388 | 4842189⋯4842965 | 776 | crtW | |

| Ava_1693 | YP_322210 | 2121129⋯2122049 | 920 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501 | CwatDRAFT_1377 | ZP_00518170 | 3068⋯3892 | 824 | d9 |

| CwatDRAFT_3226 | ZP_00516843 | 22017⋯23066 | 1049 | d12 | |

| CwatDRAFT_5150 | ZP_00515010 | 150888⋯151982 | 1049 | d12 | |

| CwatDRAFT_3625 | ZP_00516181 | 10760⋯11809 | 1049 | d15 | |

| CwatDRAFT_1857 | ZP_00517700 | 1398⋯2231 | 834 | hypothetical protein | |

| CwatDRAFT_5424 | ZP_00514501 | 315629⋯316522 | 893 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Gloeobacter violaceus strain PCC 7421 | gvip390 | NP_925812 | 3057506⋯3058357 | 851 | d9 |

| gvip170 | NP_924181 | 1312274⋯1313095 | 822 | d9 | |

| gll1946 | NP_924892 | 2071551⋯2072504 | 953 | d9 | |

| gll1947 | NP_924893 | 2072509⋯2073507 | 998 | d9 | |

| gll1938 | NP_924884 | 2060880⋯2061839 | 959 | d9 | |

| gll1940 | NP_924886 | 2063884⋯2064876 | 992 | d9 | |

| gvip364 | NP_925569 | 2779580⋯2780638 | 1058 | d12 | |

| gvip506 | NP_926681 | 3944843⋯3945910 | 1058 | d12 | |

| gll0171 | NP_923117 | 161268⋯162440 | 1173 | hypothetical protein | |

| gll2501 | NP_925447 | 2660474⋯2661475 | 1001 | mocD | |

| gvip239 | NP_924674 | 1833712⋯1834485 | 773 | crtW | |

|

| |||||

| Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133(PCC 73102) | Npun02000467 | ZP_00345918 | 175651⋯176532 | 881 | d9 |

| Npun02005010 | ZP_00108582 | 41108⋯41929 | 821 | d9 | |

| Npun02005011 | ZP_00108583 | 42265⋯43326 | 1061 | d12 | |

| Npun02005012 | ZP_00108584 | 43524⋯44603 | 1080 | d15 | |

| Npun02001904 | ZP_00345765 | 63255⋯64310 | 1056 | hypothetical protein | |

| Npun02001905 | ZP_00110890 | 64537⋯65574 | 1038 | hypothetical protein | |

| Npun02002344 | ZP_00110549 | 77763⋯78863 | 1101 | hypothetical protein | |

| Npun02003462 | ZP_00109371 | 76020⋯76964 | 945 | mocD | |

| Npun02000865 | ZP_00345866 | 139810⋯140571 | 762 | crtW | |

| Npun02001326 | ZP_00111258 | 55604⋯56392 | 788 | crtW | |

| Npun02006805 | ZP_00106832 | 23657⋯24556 | 899 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. NATL1A | NATL1_21421 | YP_001015962 | 1799954⋯1800733 | 780 | d9 |

| NATL1_10821 | YP_001014905 | 992775⋯993992 | 1218 | d12 | |

| NATL1_03151 | YP_001014144 | 291853⋯292884 | 1032 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus strain NATL2A | PMN2A_1271 | YP_292464 | 1227545⋯1228474 | 929 | d9 |

| PMN2A_0393 | YP_291588 | 388657⋯389874 | 1217 | d12 | |

| PMN2A_1603 | YP_292794 | 1566557⋯1567588 | 1031 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus MIT 9211 | P9211_09157 | ZP_01006363 | 1417821⋯1418765 | 944 | d9 |

| P9211_05577 | ZP_01005647 | 779723⋯780334 | 611 | d12 | |

| P9211_05582 | ZP_01005648 | 780304⋯780729 | 425 | d12 | |

| P9211_07547 | ZP_01006041 | 1108444⋯1109469 | 1015 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. MIT 9301 | P9301_18621 | YP_001092086 | 1588713⋯1589651 | 939 | d9 |

| P9301_15761 | YP_001091800 | 1328773⋯1329939 | 1167 | d12 | |

| P9301_15721 | YP_001091796 | 1326076⋯1327182 | 1107 | d12 | |

| P9301_02581 | YP_001090482 | 239249⋯239974 | 726 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. MIT 9303 | P9303_28951 | YP_001018890 | 2560285⋯2561250 | 966 | d9 |

| P9303_28931 | YP_001018888 | 2558615⋯2559535 | 921 | d9 | |

| P9303_14121 | YP_001017424 | 1208715⋯1209800 | 1086 | d12 | |

| P9303_21081 | YP_001018108 | 1869188⋯1870330 | 1143 | d12 | |

| P9303_24321 | YP_001018428 | 2137288⋯2138328 | 1041 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. MIT 9312 | PMT9312_1764 | YP_398261 | 1656076⋯1657014 | 938 | d9 |

| PMT9312_1476 | YP_397972 | 1385670⋯1386845 | 1175 | d12 | |

| PMT9312_1473 | YP_397969 | 1382796⋯1383902 | 1106 | d12 | |

| PMT9312_0238 | YP_396735 | 229042⋯229842 | 800 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. MIT 9313 | PMT2172 | NP_895996 | 2299082⋯2300002 | 920 | d9 |

| PMT2174 | NP_895998 | 2300938⋯2301717 | 779 | d9 | |

| PMT0249 | NP_894082 | 278544⋯279683 | 1139 | d12 | |

| PMT0797 | NP_894629 | 872385⋯873470 | 1085 | d12 | |

| PMT1816 | NP_895643 | 1920323⋯1921363 | 1040 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. AS9601 | A9601_18811 | YP_001010271 | 1616719⋯1617657 | 939 | d9 |

| A9601_15921 | YP_001009982 | 1355480⋯1356514 | 1035 | d12 | |

| A9601_15871 | YP_001009977 | 1352826⋯1353932 | 1107 | d12 | |

| A9601_02571 | YP_001008652 | 238284⋯239117 | 834 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus str. MIT 9515 | P9515_18621 | YP_001012176 | 1650943⋯1651929 | 987 | d9 |

| P9515_15601 | YP_001011874 | 1376566⋯1377693 | 1128 | d12 | |

| P9515_15521 | YP_001011866 | 1371646⋯1372752 | 1107 | d12 | |

| P9515_02681 | YP_001010584 | 247534⋯248433 | 900 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus subsp. marinus str. CCMP1375 (SS120) | Pro1833 | NP_876224 | 1690865⋯1691797 | 932 | d9 |

| Pro1208 | NP_875600 | 1116904⋯1118016 | 1112 | d12 | |

| Pro1214 | NP_875606 | 1121144⋯1122250 | 1106 | d12 | |

| Pro0266 | NP_874660 | 261189⋯262223 | 1034 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus subsp. marinus str. CCMP1986 (MED4) | PMM1672 | NP_893789 | 1604745⋯1605731 | 986 | d9 |

| PMM1382 | NP_893499 | 1331162⋯1332340 | 1178 | d12 | |

| PMM1378 | NP_893495 | 1325388⋯1326494 | 1106 | d12 | |

| PMM0236 | / | 228281⋯229270 | 989 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus elongatus strain PCC 7942 | Synpcc7942_2561 | YP_401578 | 2639146⋯2639982 | 836 | d9 |

| Synpcc7942_1713 | YP_400730 | 1781317⋯1782219 | 902 | mocD | |

| Synpcc7942_2439 | YP_401456 | 2514276⋯2515271 | 995 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus elongatus strain PCC 6301 | syc1549_d | YP_172259 | 1676804⋯1677640 | 837 | d9 |

| Syc2378_c | YP_173088 | 2534831⋯2535691 | 861 | mocD | |

| syc1667_c | YP_172377 | 1801757⋯1802752 | 996 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. BL107 | BL107_07284 | ZP_01469203 | 490784⋯491566 | 782 | d9 |

| BL107_07289 | ZP_01469204 | 491936⋯492721 | 785 | d9 | |

| BL107_06084 | ZP_01468963 | 247334⋯248356 | 1022 | d12 | |

| BL107_14110 | ZP_01468055 | 331111⋯331884 | 773 | crtW | |

| BL107_08054 | ZP_01469357 | 636707⋯637738 | 1031 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. CC9311 | sync_2793 | YP_731981 | 2458778⋯2459710 | 932 | d9 |

| sync_2791 | YP_731979 | 2457075⋯2457986 | 911 | d9 | |

| sync_0336 | YP_729569 | 344430⋯345449 | 1019 | crtR | |

| sync_0396 | YP_729627 | 408306⋯409505 | 1199 | d12 | |

| sync_1804 | YP_731008 | 1621108⋯1621869 | 761 | crtW | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. CC9605 | Syncc9605_2541 | YP_382824 | 2358792⋯2359703 | 911 | d9 |

| Syncc9605_1972 | YP_382268 | 1793076⋯1794221 | 1145 | d12 | |

| Syncc9605_0286 | YP_380617 | 292821⋯293870 | 1049 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. CC9902 | Syncc9902_2191 | YP_378192 | 2099771⋯2100673 | 902 | d9 |

| Syncc9902_2192 | YP_378193 | 2100902⋯2101825 | 923 | d9 | |

| Syncc9902_0141 | YP_376159 | 149723⋯150724 | 1001 | d12 | |

| Syncc9902_0972 | YP_376982 | 954015⋯954788 | 773 | crtW | |

| Syncc9902_2058 | YP_378059 | 1964618⋯1965730 | 1112 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. JA-2-3B′a(2-13) | CYB_0861 | YP_477105 | 894187⋯895071 | 884 | d9 |

| CYB_2914 | YP_479096 | 3011594⋯3012520 | 926 | mocD | |

| CYB_0102 | YP_476366 | 118335⋯119306 | 971 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. JA-3-3Ab | CYA_2349 | YP_475739 | 2357019⋯2357912 | 893 | d9 |

| CYA_1931 | YP_475340 | 1944066⋯1945040 | 974 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. RCC307 | SynRCC307_2395 | YP_001228651 | 2091372⋯2092274 | 903 | d9 |

| SynRCC307_2393 | YP_001228649 | 2089667⋯2090581 | 915 | d9 | |

| SynRCC307_1757 | YP_001228013 | 1538507⋯1539562 | 1056 | d12 | |

| SynRCC307_1993 | YP_001228249 | 1729342⋯1730103 | 762 | crtW | |

| SynRCC307_2209 | YP_001228465 | 1915148⋯1916167 | 1020 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. RS9916 | RS9916_36767 | ZP_01471384 | 1050409⋯1051341 | 932 | d9 |

| RS9916_36757 | ZP_01471382 | 1048603⋯1049568 | 965 | d9 | |

| RS9916_39311 | ZP_01472905 | 116650⋯117675 | 1025 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. RS9917 | RS9917_06370 | ZP_01079314 | 447782⋯448705 | 923 | d9 |

| RS9917_06360 | ZP_01079312 | 446060⋯446992 | 932 | d9 | |

| RS9917_03333 | ZP_01080849 | 99968⋯101047 | 1079 | d12 | |

| RS9917_00687 | ZP_01080541 | 64826⋯65563 | 737 | crtW | |

| RS9917_03663 | ZP_01080915 | 166940⋯167902 | 962 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. WH 5701 | WH5701_02025 | ZP_01084898 | 299319⋯300257 | 787 | d9 |

| WH5701_02015 | ZP_01084896 | 297579⋯298532 | 953 | d9 | |

| WH5701_14646 | ZP_01083974 | 104382⋯105539 | 1157 | d12 | |

| WH5701_16535 | ZP_01086617 | 164⋯1186 | 1022 | d12 | |

| WH5701_06521 | ZP_01085935 | 65353⋯66231 | 878 | hypothetical protein | |

| WH5701_02369 | ZP_01084322 | 42300⋯43271 | 971 | mocD | |

| WH5701_04005 | ZP_01083421 | 43734⋯44519 | 785 | crtW | |

| WH5701_01215 | ZP_01084736 | 138584⋯139615 | 1031 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. WH 7803 | SynWH7803_2417 | YP_001226140 | 2249293⋯2250087 | 795 | d9 |

| SynWH7803_2415 | YP_001226138 | 2247475⋯2248386 | 912 | d9 | |

| SynWH7803_0589 | YP_001224312 | 594539⋯595603 | 1065 | d12 | |

| SynWH7803_1625 | YP_001225348 | 1496144⋯1497139 | 996 | d15 | |

| SynWH7803_0928 | YP_001224651 | 871421⋯872167 | 747 | crtW | |

| SynWH7803_0337 | YP_001224060 | 361336⋯362337 | 1002 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. WH 7805 | WH7805_10184 | ZP_01125021 | 209067⋯209999 | 932 | d9 |

| WH7805_10194 | ZP_01125023 | 210769⋯211680 | 911 | d9 | |

| WH7805_06186 | ZP_01124768 | 405535⋯406059 | 524 | d12 | |

| WH7805_04931 | ZP_01124517 | 184338⋯185516 | 1178 | d12 | |

| WH7805_01197 | ZP_01123773 | 3991⋯4734 | 743 | crtW | |

| WH7805_07481 | ZP_01123496 | 193165⋯194193 | 1028 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechococcus sp. WH 8102 | SYNW2377 | NP_898466 | 2286168⋯ 2287028 | 860 | d9 |

| SYNW0696 | NP_896789 | 679330⋯680478 | 1148 | d12 | |

| SYNW1696 | NP_897787 | 1631011⋯1632147 | 1136 | d12 | |

| SYNW1368 | NP_897461 | 1354793⋯1355527 | 734 | crtW | |

| SYNW0291 | NP_896386 | 291323⋯292354 | 1031 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | sll0541 | NP_442430 | 2822579⋯2823535 | 956 | d9 |

| slr1350 | NP_441489 | 1746308⋯1747363 | 1055 | d12 | |

| sll1441 | NP_441622 | 1895520⋯1896599 | 1079 | d15 | |

| sll0262 | NP_441824 | 2120067⋯2121146 | 1079 | d6 | |

| Sll1611 | NP_441220 | 1462136⋯1463245 | 1110 | hypothetical protein | |

| sll1468 | NP_440788 | 981691⋯982629 | 938 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Thermosynechococcus elongatus strain BP-1 | tll1719 | NP_682509 | 1800682⋯1801521 | 839 | d9 |

| tlr2380 | NP_683170 | 2490209⋯2491048 | 839 | d9 | |

| tlr1653 | NP_682443 | 1733919⋯1734767 | 848 | d9 | |

| tlr1254 | NP_682044 | 1300388⋯1301308 | 920 | mocD | |

| tlr1900 | NP_682690 | 1986642⋯1987529 | 887 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 | Tery_1437 | YP_721205 | 2173203⋯2174015 | 812 | d9 |

| Tery_0142 | YP_720110 | 207806⋯208861 | 1055 | d12 | |

| Tery_4492 | YP_723951 | 6931402⋯6932475 | 1073 | d15 | |

| Tery_3898 | YP_723406 | 6024293⋯6025342 | 1050 | hypothetical protein | |

| Tery_2925 | YP_722564 | 4543239⋯4544114 | 875 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106 | L8106_03152 | ZP_01624678 | 2253⋯3071 | 818 | d9 |

| L8106_27002 | ZP_01621185 | 94912⋯95955 | 1043 | d12 | |

| L8106_10697 | ZP_01624560 | 6961⋯8043 | 1082 | d15 | |

| L8106_14825 | ZP_01619238 | 100018⋯101133 | 1115 | d6 | |

| L8106_06180 | ZP_01620148 | 172993⋯173604 | 611 | hypothetical protein | |

| L8106_18641 | ZP_01624278 | 13290⋯14111 | 821 | hypothetical protein | |

| L8106_30215 | ZP_01622578 | 23391⋯24185 | 794 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Nodularia spumigena CCY9414 | N9414_19077 | ZP_01631817 | 16235⋯17026 | 791 | d9 |

| N9414_07494 | ZP_01632615 | 317⋯1135 | 818 | d9 | |

| N9414_07499 | ZP_01632616 | 1303⋯2427 | 1124 | d12 | |

| N9414_07504 | ZP_01632617 | 2618⋯3688 | 1070 | d15 | |

| N9414_07509 | ZP_01632618 | 4087⋯5178 | 1091 | d6 | |

| N9414_18293 | ZP_01629726 | 29633⋯30223 | 590 | hypothetical protein | |

| N9414_07726 | ZP_01632305 | 4851⋯5633 | 782 | crtW | |

| N9414_01572 | ZP_01632726 | 697⋯1587 | 890 | crtR | |

|

| |||||

| Cyanothece sp. CCY0110 | CY0110_10577 | ZP_01726409 | 185891⋯186724 | 834 | d9 |

| CY0110_05582 | ZP_01729213 | 74180⋯75004 | 825 | d9 | |

| CY0110_10917 | ZP_01732458 | 7951⋯9000 | 1050 | d12 | |

| CY0110_00445 | ZP_01728541 | 90142⋯91191 | 1050 | d15 | |

| CY0110_24056 | ZP_01727982 | 158769⋯159887 | 1119 | d6 | |

| CY0110_13441 | ZP_01729024 | 60390⋯61220 | 831 | hypothetical protein | |

| CY0110_27283 | ZP_01731934 | 15787⋯16914 | 1128 | hypothetical protein | |

| CY0110_11357 | ZP_01729279 | 9512⋯10513 | 1002 | mocD | |

| CY0110_08481 | ZP_01731007 | 25752⋯26747 | 996 | crtR | |

Table 2.

List of organisms (except the above thirty seven cyanobacteria) and protein sequences analyzed in this study. Note: micro represents Microsomal, chl represents Chloroplastic, “uncertain” means that the function of the gene is uncertain.

| Species | Accession no/locus tag | Label | Accession no/locus tag | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | BAA25180 | d9 | AAB60302 | chld15 |

| Q949X0 | d7 | BAA05514 | microd15 | |

| AAA92800 | chld12 | CAA11858 | d8 | |

| NP_187819 | microd12 | |||

|

| ||||

| Thalassiosira pseudonana | Tp22511 | d9 | AY817152 | d5 |

| Tp23798 | d12 | AY817155 | d6 | |

| Tp3143 | d12 | AY817154 | d8 | |

| AY817156 | d4 | |||

|

| ||||

| Phaeodactylum tricorutum | AAW70158 | d9 | AY082393 | d6 |

| AAO23565 | chld12 | AY082392 | d5 | |

| AY165023 | microd12 | Pt22459 | d5 | |

|

| ||||

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Cr117883 | uncertain | ABL09485 | d15 |

| AB007640 | chld12 | AY860820 | crtW | |

| EDP04777 | microd12 | |||

|

| ||||

| Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 | AAB61353 | d9 | AAF21445 | d12 |

| AAF21447 | uncertain | AAB61352 | d15 | |

|

| ||||

| Nostoc sp. SO-36 | CAF18426 | d9 | CAF18425 | d15 |

| CAF18423 | d9 | CAF18424 | d12 | |

|

| ||||

| Mortierella alpina | CAB38177 | d9 | AAF08684 | d12 |

| AAF08685 | d6 | AAC39508 | d5 | |

|

| ||||

| Cyanidioschyzon merolae | BAA28834 | d9 | CMK291C | d12 |

| CMJ201C | d9 | BAC76126 | crtR | |

|

| ||||

| Arthrospira platensis | CAA05166 | d9 | Q54794 | d12 |

| ABN11122 | d6 | |||

|

| ||||

| Ostreococcus lucimarinus | Ol51664 | uncertain | Ol24150 | d12 |

| Ol18582 | d12 | |||

|

| ||||

| Caenorhabditis elegans | AAF97550 | d9 | AAC15586 | d6 |

| AAC95143 | d5 | |||

|

| ||||

| Rattus norvegicus | NP_114029 | d9 | BAA75496 | d6 |

| AAG35068 | d5 | |||

|

| ||||

| Homo sapiens | XP_005719 | d9 | AAD20018 | d6 |

| AAF29378 | d5 | |||

|

| ||||

| Brassica napus | AAA50157 | chl d12 | AAF78778 | microd12 |

| CAA11857 | d8 | |||

|

| ||||

| Chlorella vulgaris | AB075526 | microd12 | AB075527 | microd15 |

| Chlamydomonas sp. W80 | AB031546 | chld12 | ||

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714 | BAA02921 | d12 | ||

| Mucor circinelloides | AAD55982 | d12 | BAB69055 | d6 |

| Emericella nidulans | AAG36933 | d12 | ||

| Glycine max | BAD89862 | microd12 | ||

| Calendula officinalis | AAK26633 | microd12 | ||

| Gossypium hirsutum | AAL37484 | microd12 | ||

| Nicotiana tabacum | BAC01274 | chld15 | BAC01273 | microd15 |

| Brassica juncea | CAB85467 | chld15 | ||

| Picea abies | CAC18722 | chld15 | ||

| Ricinus communis | AAA73511 | chld15 | AAC49010 | 12-hydroxylase |

| Triticum aestivum | BAA28358 | microd15 | ||

| Oryza sativa | BAA11397 | microd15 | ||

| Vernicia fordii | AAN87573 | microd12 | AAN87574 | 12-conjugase |

| Punica granatum | CAD24671 | microd12 | AAO37753 | 12-conjugase |

| Lesquerella fendleri | AAC32755 | 12-hydroxylase/desaturase | ||

| Physaria lindheimeri | ABQ01458 | 12-hydroxylase | ||

| Crepis palaestina | CAA76156 | 12-epoxygenase | ||

| Stokesia laevis | AAR23815 | 12-epoxygenase | ||

| Daucus carota | AAO38033 | 12-acetylenase | ||

| Foeniculum vulgare | AAO38034 | 12-acetylenase | ||

| Hedera helix | AAO38031 | 12-acetylenase | ||

| Helianthus annuus | AAO38032 | 12-acetylenase | CAA60621 | d8 |

| Helichrysum bracteatum | AAO38037 | 12-acetylenase | ||

| Rudbeckia hirta | AAO38035 | 12-acetylenase | ||

| Crepis alpina | CAA76158 | 12-acetylenase | ||

| Calendula officinalis | AAK26632 | 12-conjugase | ||

| Trichosanthes kirilowii | AAO37751 | 12-conjugase | ||

| Acheta domesticus | AAK25797 | d9 | ||

| Cyprinus carpio | CAB57858 | d9 | ||

| Drosophila simulans | CAB52475 | d9 | ||

| Gallus gallus | CAA42997 | d9 | ||

| Helicoverpa zea | AAF81790 | d9 | ||

| Rosa hybrid cultivar | BAA23136 | d9 | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | AAA34826 | d9 | ||

| Limnanthes douglasii | AAG28599 | d9 | ||

| Prochlorothrix hollandica | AAG16761 | d9 | ||

| Lyngbya majuscula | AAS98775 | d9 | ||

| Synechococcus vulcanus | AAD00699 | d9 | ||

| Thraustochytrium sp. ATCC21685 | AAM09688 | d4 | AAM09687 | d5 |

| Euglena gracilis | AAQ19605 | d4 | AF139720 | d8 |

| Pavlova lutheri | AY332747 | d4 | ||

| Isochrysis galbana strain CCMP1323 | AY630574 | d4 | ||

| Marchantia polymorpha | AAT85663 | d5 | AAT85661 | d6 |

| Nitzschia closterium f. minutissima | AY603475 | d5 | ||

| Dictyostelium discoideum | BAA37090 | d5 | ||

| Bacillus subtilis | AAC38355 | d5 | ||

| Danio rerio | Q9DEX7 | d5/d6 | ||

| Borago officinalis | AAD01410 | d6 | AAG43277 | d8 |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | AAK26745 | d6 | ||

| Mus musculus | NP_062673 | d6 | ||

| Glossomastix chrysoplasta | AAU11444 | d6 | ||

| Ostreococcus tauri | AY746357 | d6 | ||

| Physcomitrella patens | CAA11033 | d6 | ||

| Echium pitardii | AAL23581 | d6 | ||

| Chlorella zofingiensis | AY772713 | crtW | ||

| Cyanidium caldarium | AAB82698 | crtR | ||

| Haematococcus pluvialis | CAA60478 | crtW | ||

| Myxococcus xanthus DK 1622 | YP_634431 | uncertain | ||

| Stigmatella aurantiaca DW4/3-1 | ZP_01463016 | uncertain | ||

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 | NP_771234 | uncertain | ||

2.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Sequence alignments were generated using Clustal W program [17]. The SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and PFAM (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) databases were used to search the conserved domains of the putative desaturase enzymes. The conserved amino acid residues of different conserved domains were manually identified using the BioEdit sequence editor. The final alignment was further refined after excluding the poorly conserved regions at the protein ends, and consisted of sequences spanning the conserved domains. The neighbor-joining (NJ) and minimum-evolution (ME) methods in MEGA4 [18] were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. To maximize the number of sites available for analysis, two partial sequences from Synechococcus sp. WH 7805 (ZP_01124768, 174 aa) and Nodularia spumigena CCY9414 (ZP_01629726, 196 aa) were excluded. Bootstrap with 1000 replicates was used to establish the confidence limit of the tree branches.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. The Conserved Motifs

Using BlastP and TBlastN programs with the query sequences to search the 37 genomes of cyanobacteria, 193 protein sequences were identified including fatty acid desaturase, fatty acid dehydrogenase, hypothetical protein, β-carotene ketolase, β-carotene hydroxylase, and hydrocarbon oxygenase. PFAM and SMART domain analyses could not distinguish fatty acid desaturase from fatty acid dehydrogenase, β-carotene ketolase, β-carotene hydroxylase, or hydrocarbon oxygenase. Moreover, most of the protein sequences which were originally annotated as fatty acid desaturase were not classified into Δ9, Δ12, Δ15, or Δ6 desaturase categories. To facilitate the classification of different types of desaturases, the conserved motifs of different enzymes were identified by multiple sequence alignments with Clustal W.

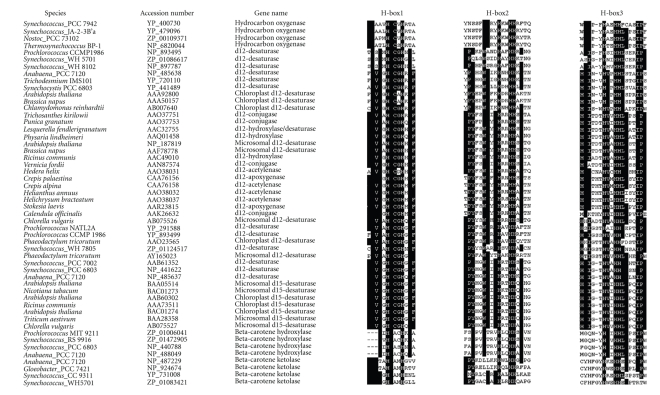

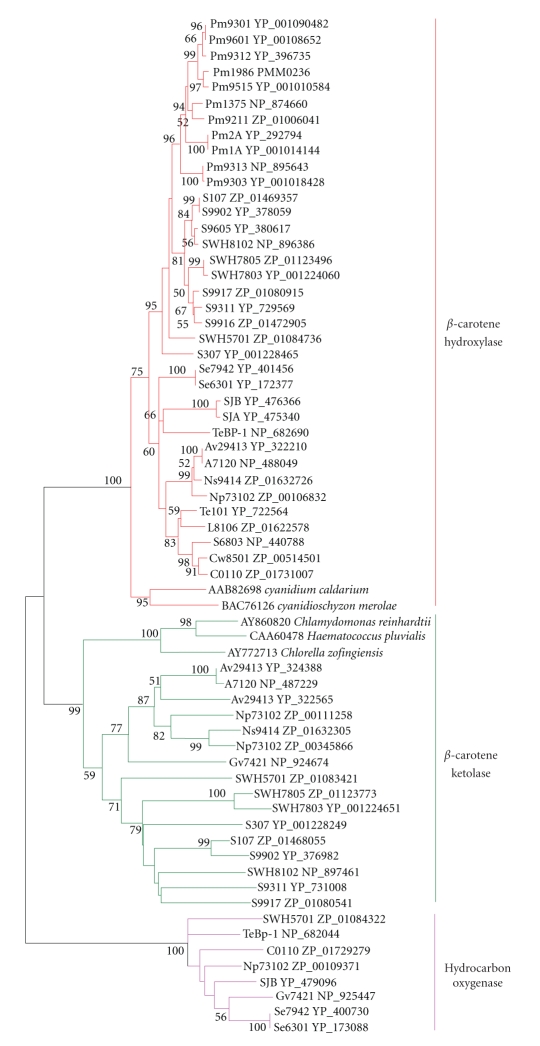

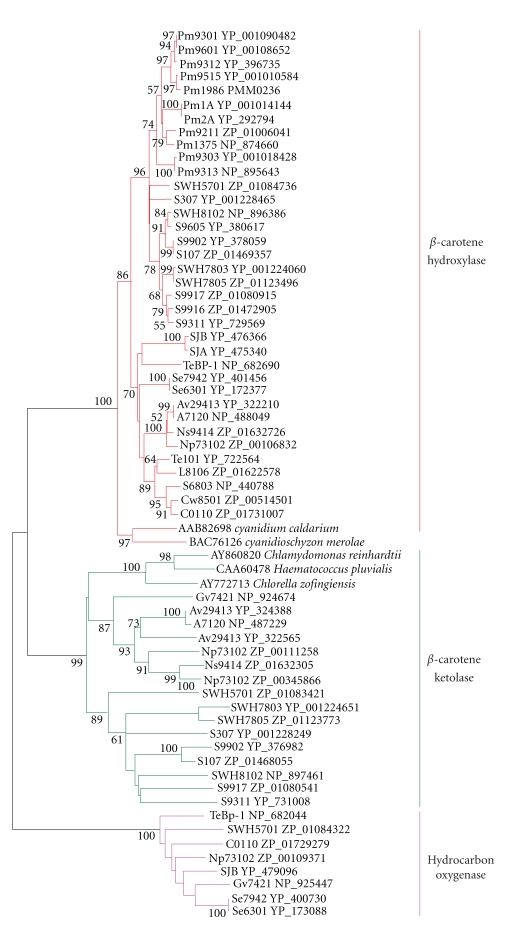

There were three typical histidine-rich motifs existed in all the proteins similar to proven cyanobacterial fatty acid desaturases (Table 3). Moreover, there were different conserved residues in the same histidine-boxes of different kinds of proteins, suggesting that these proteins might have acquired different functions from a common ancestor during the evolution. According to the different conserved residues of three histidine-motifs and phylogenetic profile, 16 β-carotene ketolases, 36 β-carotene hydroxylases, and 8 hydrocarbon oxygenases (MocD, a rhizopine oxygenase for the conversion of 3-O-MSI to SI)) were identified from the 37 cyanobacterial genomes (Figures 2, 4, and 5).

Table 3.

Conserved motifs of membrane desaturases in cyanobacteria. Note: X represents an unspecified amino acid. Δ9-1: clade 1 of Δ9 homologous genes, Δ9-2: clade 2 of Δ9 homologous genes, Δ9-3: clade 3 of Δ9 homologous genes, Δ9-4: clade 4 of Δ9 homologous genes, Δ9-5: clade 5 of Δ9 homologous genes, Δ12a : clade 3 of Δ12 homologous genes, Δ12b: clade 1 of Δ12 homologous genes, Δ12c : clade 4 of Δ12 homologous genes, Δ15: Δ15 desaturase, Δ6: Δ6 desaturase.

| Name | H-box1 | H-box2 | H-box3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-carotene ketolase | TGLFIX2HDXMH | K(N)HX2HH | CY(F)H(N)FGYHXEHH |

| β-carotene hydroxylase | GTVIHDAS(C)HX2AH | RVHL(M)Q(E)HHXHVN | GQNYHLI(V)HHLWPSI(V)PW |

| hydrocarbon oxygenase | HECXHRTAFA | FY(F)RRYHXWHHRXT | MWNMPF(Y)HXEHHL(F) |

| Δ9-1 | GICLGYHRLLXHKSF | WX3HRXHHAX3D | YGEGWHNNHHX2PX5GX2WWE |

| Δ9-2 | GXTLGXHRX3HRSF | WXGXHRXHHX2SD | GEGWHNNHHX4SARHGXXWWE |

| Δ9-3 | TVLGVTLGLHRLXAHRS | WX2LHRHHHX2SDQ | WVAXLSFGEGWHNNHHAXPXSARHGL |

| Δ9-4 | CLGVTXGYHRLLXHRX2 | WXGLHRHHHXFSDT | WVAALTFGEGWHNNHHAXPXSA |

| Δ9-5 | GX4GXHRXFXHX2F | WX3HRXHHX3D | GESWHNNHHXFX3AX2G |

| Δ12a | FVXGHDCGHRSF | WRX2HX2HHX2TN | HXPHHX4IPXYNLR |

| Δ12b | WVXAHECGHXAFH | WX2SHX2HHX3N | HX2HHX4PHYXA |

| Δ12c | FSLMHDCGHXSLF | WSX2HAXHHX2NG | HX2HHLXERIPNYXL |

| Δ15 | FWXLFVVGHDCGHXSFS | HGWRISHRTHHXNTGN | IHHXIGTHVAHHIF |

| Δ6 | HDX2HX3S | WX3HX2LHHXYTNI | GGLNXQ(H)X2HHLFPXICH |

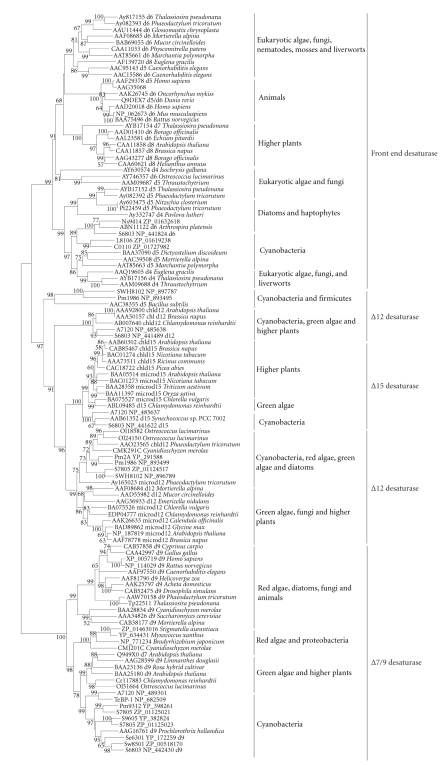

Figure 2.

Comparison of the three conserved histidine-rich motifs of proteins from cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, and higher plants, including Δ12 fatty acid desaturase, Δ15 fatty acid desaturase, β-carotene ketolase, β-carotene hydroxylase, hydrocarbon oxygenase, Δ12 fatty acid epoxygenase, Δ12 fatty acid acetylenase, Δ12 fatty acid conjugase, and Δ12 fatty acid hydroxylase. The conserved amino acid residues are in black. “Microsomal” represents the microsome-type desaturases, “Chloroplast” represents the chloroplast-type desaturases.

Figure 4.

Neighbor-joining tree of β-carotene ketolase, β-carotene hydroxylase, and hydrocarbon oxygenase homologs of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae. About 220 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Colored branches indicate different groups of proteins. Red: β-carotene hydroxylase, green: β-carotene ketolase, magenta: hydrocarbon oxygenase. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from neighbor-joining analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

Figure 5.

Minimum-evolution tree of β-carotene ketolase, β-carotene hydroxylase, and hydrocarbon oxygenase homologs of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae. About 220 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Colored branches indicate different groups of proteins. Red: β-carotene hydroxylase, green: β-carotene ketolase, magenta: hydrocarbon oxygenase. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from minimum-evolution analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

3.2. Discovery of Candidate Genes for Δ9 Desaturases

To elucidate the phylogenetic relationships among different membrane desaturases, genes from cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, higher plants, fungi, invertebrates, and vertebrates were analyzed using neighbor-joining (NJ) and minimum-evolution (ME) methods. Observation of the tree revealed that all the desaturases fell into three distinct subfamilies (Figures 12 and 13): Δ9 desaturase subfamily, Δ12/ω3 desaturases subfamily, and the front-end desaturases subfamily.

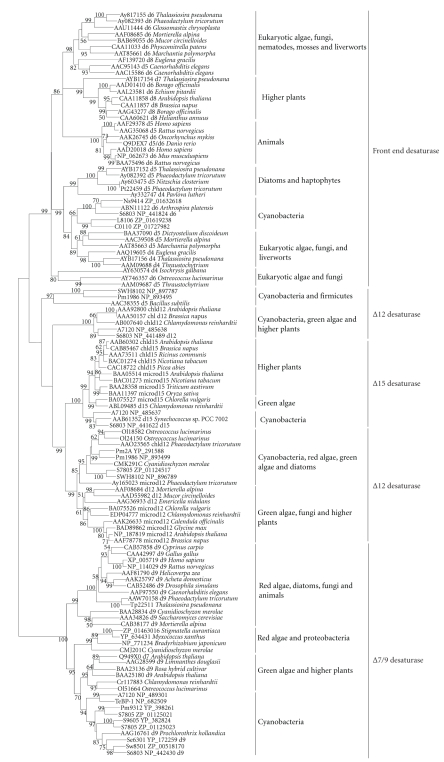

Figure 12.

Neighbor-joining tree of membrane desaturases. About 330 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from neighbor-joining analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

Figure 13.

Minimum-evolution tree of membrane desaturases. About 330 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from minimum-evolution analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

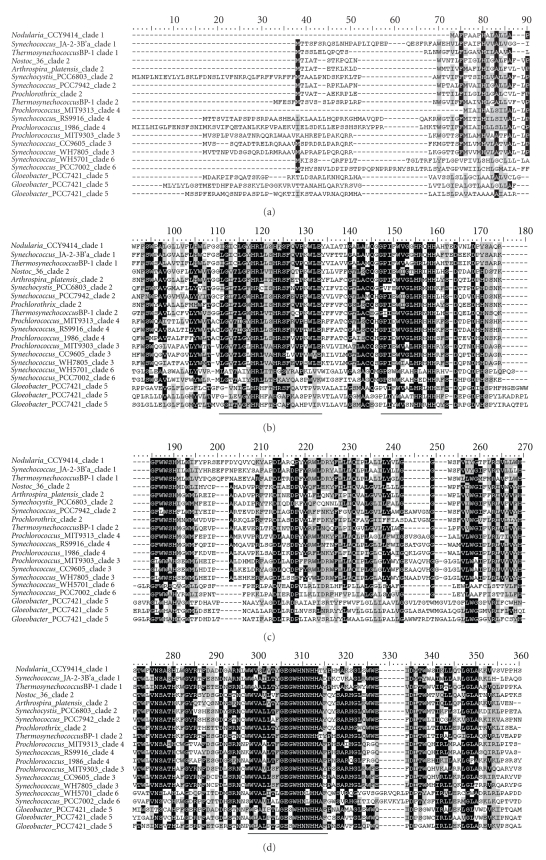

As shown in Figures 12 and 13, Δ9 desaturases clustered into a single-monophyletic group, thus were analyzed separately from other types of desaturases. Six clades could be identified within the Δ9 desaturase homologs from cyanobacteria based on high-bootstrap support values and a large degree of within-clade sequence identity (Figures 3, 6, and 7). Except for the genes from Clade 6 (ZP_01620148, ZP_01085935, and AAF21447) whose second residue of the second histidine-box was not arginine, the genes from other clades all matched the standard for Δ9 desaturase, that is, HR-X3-H, HR-X-HH, and HN-X-HH. Thus, genes from Clade 6 are assigned as hypothetical proteins with functions unknown.

Figure 3.

Alignment of the complete deduced amino acid sequences of Δ9-homologous genes. Amino acid residues that are conserved are highlighted in black boxes. The conserved His clusters and their associated conserved domains are underlined. The limits of the domains are indicated by the residue positions, on top of the sequence. The sequences are denoted by their strain names and the clades they belong to.

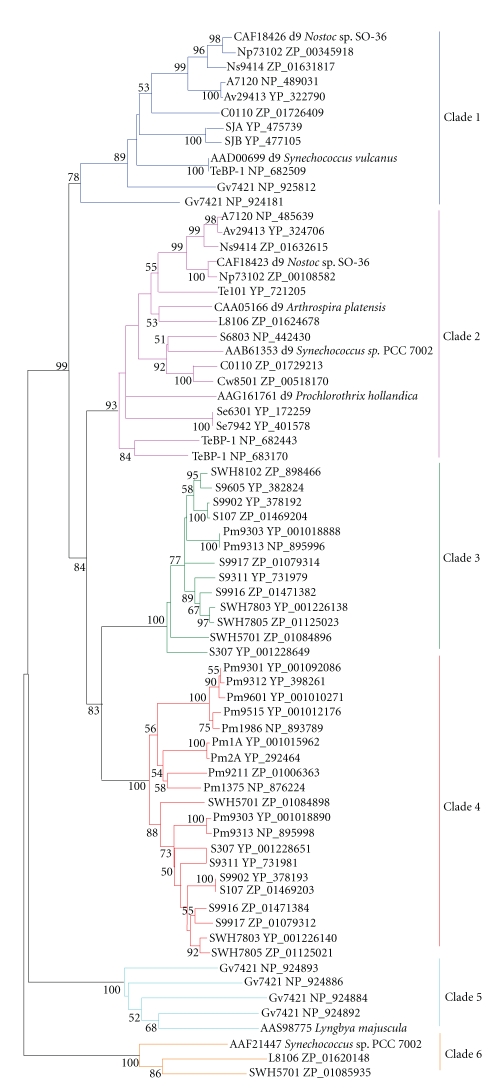

Figure 6.

Neighbor-joining tree of Δ9-homologous genes of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae. About 250 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Colored branches indicate different groups of proteins. Dark blue: Clade 1, magenta: Clade 2, green: Clade 3, red: Clade 4, light blue: Clade 5, orange: Clade 6. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from neighbor-joining analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

Figure 7.

Minimum-evolution tree of Δ9-homologous genes of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae. About 250 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Colored branches indicate different groups of proteins. Dark blue: Clade 1, magenta: Clade 2, green: Clade 3, red: Clade 4, light blue: Clade 5, orange: Clade 6. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from minimum-evolution analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

The first clade was composed by one Δ9-homologous gene from eight N2-fixing cyanobacterial species (such as Nostoc sp. strain SO-36 and Anabaena sp. PCC 7120), Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1, Synechococcus vulcanus, and two genes from Gloeobacter violaceus. The amino acid identity of these genes ranged from 50% to 98% among various cyanobacterial species. It has been proven by previous research that the Δ9 desaturase gene from Nostoc sp. strain SO-36 in this clade introduced double bonds into fatty acids that are bound to the sn-2 position of the glycerol moiety of membrane glycerolipids [19]. Moreover, the three histidine-boxes of the gene from Nostoc sp. SO-36 were consistent with those of genes in Clade 1. Therefore, the genes of Clade 1 are presumed to act on fatty acids esterified to the sn-2 position of glycerolipids.

In Clade 2, one Δ9-homologous gene from Prochlorothrix hollandica, Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942, and Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301 clustered together with two genes from Thermosynechococcus elongatus, apart from the subgroup comprised of genes from nine N2-fixing cyanobacterial species (such as Anabaena variabilis and Trichodesmium erythraeum), Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002, and Arthrospira platensis. It has been demonstrated that Thermosynechococcus elongatus has three Δ9-homologous genes that consist of one c-type and two unspecified types. By contrast, Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942, Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301, and Prochlorothrix hollandica have only one Δ9-homologous gene, which is nonspecific with respect to sn positions, acting on fatty acids at both the sn-1 and sn-2 positions [19]. Δ9 homologs from another subgroup showed high similarity with amino acid identity from 53% to 98% among various cyanobacterial species. They are strongly homologous to the genes of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (NP_442430), Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (AAB61353), and Arthrospira platensis (CAA05166) that encode Δ9 desaturases acting on C18 fatty acids at the sn-1 position. Moreover, the three histidine-boxes of these Δ9-homologous genes (HRX3HRSF, WXGXHRXHH, GEGWHNNHH) accorded with those inferred by Chintalapati et al. (2006) [19].

The Δ9-homologous genes from two unicellular marine cyanobacteria Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus constituted the third and fourth clades. Amino acid identity of genes from these two clades ranged from 54% to 98% and 65% to 99%, respectively. In addition, the two groups are closely related to Clade 2. Therefore, it is possible that these genes are homologous to the gene that encodes a Δ9 desaturase acting on C18 fatty acids at the sn-1 position or sn-1 and sn-2 positions of glycerolipids. In these two clades, 11 strains (nine Synechococcus and two low light-adapted Prochlorococcus strains) contained two Δ9-homologous genes, which clustered separately into two subgroups. It is possible that there are two paralogous genes of a common ancestor in some evolutionary lineages, such as Synechococcus sp. CC9605; however, one of them has been lost. Alternatively, acquirement of one gene from other organisms could have occurred in the evolutionary lineage, in which horizontal gene transfer (HGT) might have taken place.

Four genes of Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421 as well as JamB gene of Lyngbya majuscula integrated the fifth clade. JamB is a gene of jamaicamide biosynthetic gene cluster, and similar to a large family of membrane-associated desaturases that utilize a diiron active site to execute Δ5- or Δ9-fatty acid desaturation [20]. These genes fell into the group of proteobacterial stearoyl-CoA desaturases, far away from the other desaturase genes of cyanobacteria as analyzed by BLASTP program of NCBI (data not shown). It is probable that horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from other organisms like proteobacteria might have occurred.

Phylogenetic analyses from Figures 12 and 13 showed that Δ9 desaturases from cyanobacteria were grouped to those from green algae and higher plants, apart from red algae, diatoms, fungi, and animals. Among cyanobacterial Δ9 desaturases, the desaturase genes acting on fatty acids esterified to the sn-1 or sn-1 and sn-2 positions of glycerolipids (b-type or a-type) were placed in a basal position, while desaturase genes acting on fatty acids esterified to the sn-2 position of glycerolipids (c-type) were in the exoteric position, which indicates that a-type or b-type Δ9 desaturases may be ancestral to c-type desaturase.

3.3. Discovery of Candidate Genes for Δ12/ω3 Desaturases

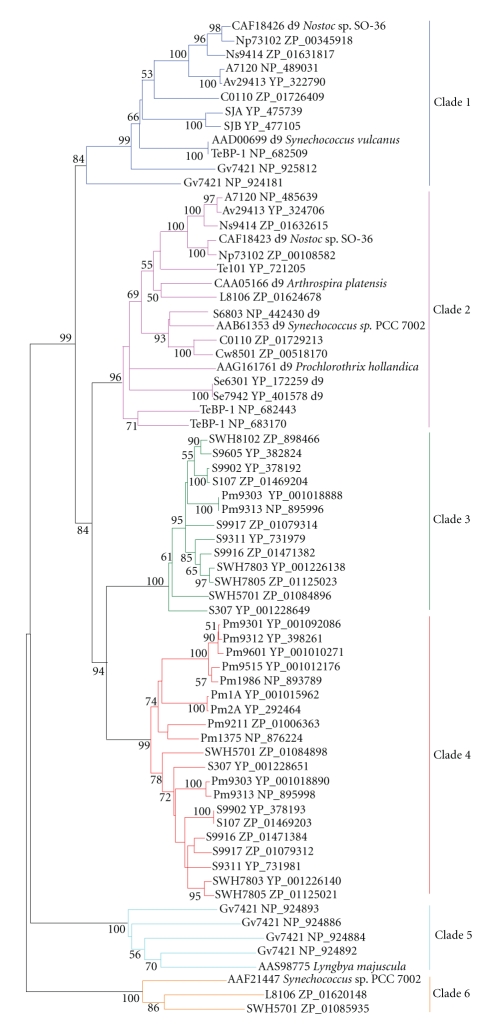

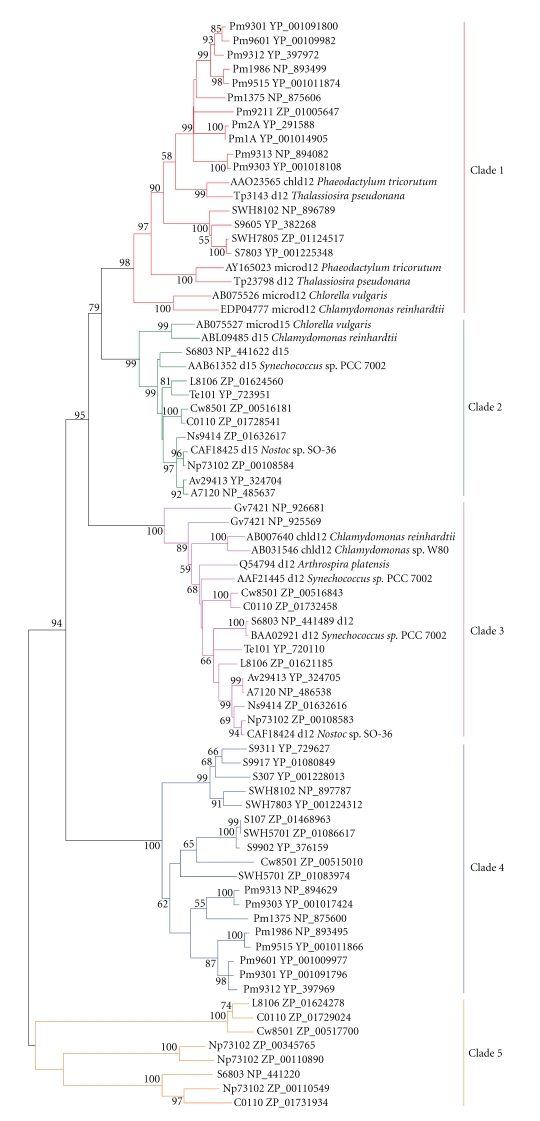

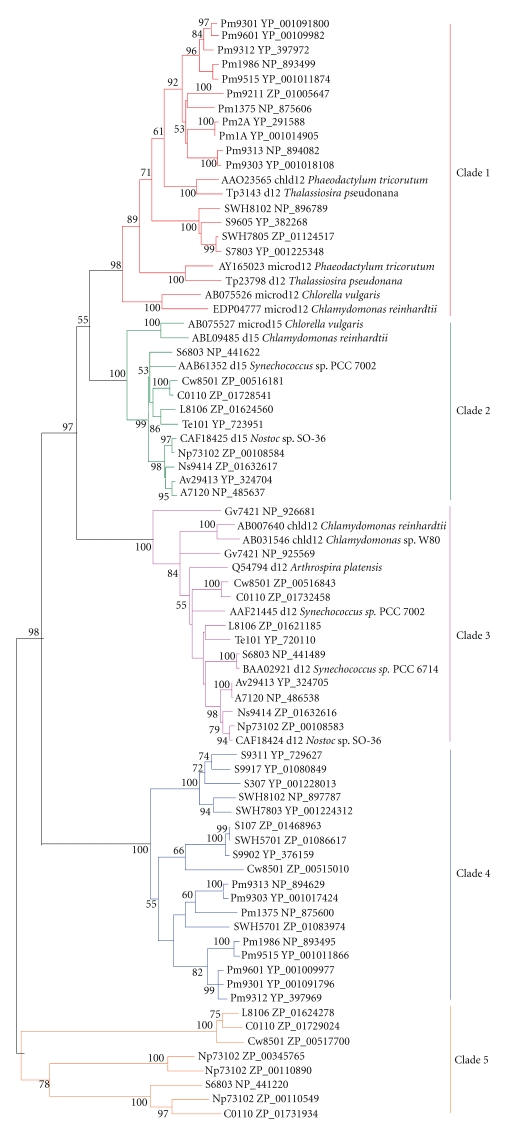

Observation on the phylogenetic tree of different membrane desaturases showed that Δ12 desaturases and Δ15 desaturases fell into the same clade (Figures 12 and 13), thus were analyzed together. As could be seen in Figures 8 and 9, the Δ12/ω3 desaturase homologs from cyanobacteria were classified into five different clades.

Figure 8.

Neighbor-joining tree of Δ12 and Δ15 homologous genes of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae. About 300 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Colored branches indicate different groups of proteins. Red: Clade 1, green: Clade 2, magenta: Clade 3, blue: Clade 4, orange: Clade 5. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from neighbor-joining analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

Figure 9.

Minimum-evolution tree of Δ12 and Δ15 homologous genes of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae. About 300 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Colored branches indicate different groups of proteins. Red: Clade 1, green: Clade 2, magenta: Clade 3, blue: Clade 4, orange: Clade 5. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from minimum-evolution analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

It was surprising that the first clade was constituted by the Δ12 homologs of marine cyanobacteria Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus, and the microsomal Δ12 desaturases of eukaryotic algae. Moreover, three histidine-boxes of the genes from cyanobacteria were represented as AHECGH, WX2SHX2HHX3N, and HX2HH (Figure 2 and Table 3), which were similar to those of microsome-type desaturases. Two partial amino acid sequences homologous to microsome-type Δ12 desaturases were revealed in Prochlorococcus marinus MIT 9211 (ZP_01005647 and ZP_01005648). One encoded an N-terminus region and the other encoded a C-terminus region. They may represent a single gene inferred from their close chromosome location of the graft genome, thus were designated as a unique gene with the accession number ZP_01005647.

The microsomal Δ12 desaturases are members of a large class of membrane-bound enzymes that contain a tripartite histidine sequence motif and two putative membrane-spanning domains. This group of membrane-bound enzymes includes desaturases, hydroxylases, epoxygenases, acetylenases, methyl oxidases and ketolases found in animals, fungi, plants, and bacteria [21–23]. The diverse reactions that these enzymes catalyze probably use a common reactive center [24]. Histidine-rich motifs are thought to form a part of the diiron center, where oxygen activation and substrate oxidation occur [25].

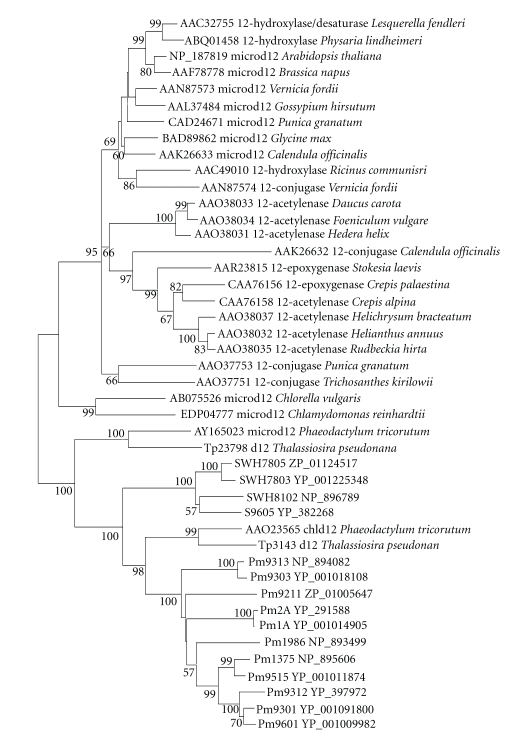

To further clarify the role of genes in Clade 1, anotherphylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor-joining (NJ) and minimum-evolution (ME) methods (Figures 10 and 11). It could be seen evidently from Figures 10 and 11 that the microsomal Δ12 desaturases from higher plants and some eukaryotic algae (such as green algae, chlorella, and chlamydomonas) fell into one group with Δ12 fatty acid hydroxylase, epoxygenase, acetylenase, and conjugase, while the genes of marine cyanobacteria clustered only with diatom plastidial and microsomal Δ12 desaturases [26]. Therefore, the microsomal Δ12 desaturases of some eukaryotic algae (such as diatom) might originate from cyanobacterial orthologs in Clade 1, and possibly horizontal gene transfer might have occurred from eukaryotic algae to Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus strains.

Figure 10.

Neighbor-joining tree of Δ12 homologous genes of cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, and higher plants. About 300 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from neighbor-joining analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

Figure 11.

Minimum-evolution tree of Δ12 homologous genes of cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algae, and higher plants. About 300 positions spanning the three histidine-boxes were employed. Sequences from 37 sequenced cyanobacterial genomes are shown by their acronyms and accession numbers (locus tags). Other sequences are shown by their accession numbers, labels, and strain names. Desaturase genes that have been functionally characterized are indicated on the tree by their labels. Bootstrap values from minimum-evolution analyses are listed to the left of each node, with values more than 50 are shown.

The ω3-homologous genes of cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae constituted the second clade. Moreover, three histidine-boxes of the genes from cyanobacteria (FVVGHDCGHXSFS, HGWRISHRTHHXNTGN, and IHHXIGTHVAHHIF) established the standard for prokaryotic Δ15 desaturase (Figure 2 and Table 3). The third clade was integrated by the Δ12 homologs of cyanobacteria and the chloroplastic Δ12 desaturases of eukaryotic algae. Moreover, three histidine-boxes of these genes were consistent with those of plastidial Δ12 desaturase that were represented as HDCGH, HX2HH, and HXPHH.

The homologous genes from Clade 4 also had three histidine-motifs (FSLMHDCGHXSLF, WSX2HAXHHX2NG, and HX2HHLXERIPNYXL) (Figure 2 and Table 3) that were similar to those of the Δ12 desaturase. As shown in Figures 12 and 13, the genes of this clade clustered with Bacillus subtilis Δ5 desaturase. Aguilar et al. (1998) demonstrated that Bacillus subtilis possessed a single desaturase. Expression of the gene in Escherichia coli resulted in desaturation of palmitic acid moieties of the membrane phospholipids to give the novel mono-UFA cis-5-hexadecenoic acid, indicating that the gene product was a Δ5 acyl-lipid desaturase [27]. However, it is well known from freshwater cyanobacteria that only four distinct desaturases, Δ9, Δ12, Δ15, and Δ6, exist in cyanobacterial cells. Therefore, the relatively close phylogenetic relationship between genes of Clade 4 and Δ5 desaturase gene of Bacillus subtilis may be due to horizontal gene transfer and the function of these genes would require further work to fully characterize.

Three genes from Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133, two genes from Cyanothece sp. CCY0110, and one gene from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501, Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106 constituted the fifth clade. It has been proven by experiments that there is only one Δ12 desaturase in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 [13]. Additionally, the three histidine-motifs of these genes were HXXXH, HXXXHH, HXXHH, among which the amounts of residues between histidines from the second histidine-box were three, while that of known cyanobacterial Δ12 desaturase were two (HXXXH, HXXHH, HXXHH). Therefore, in our analysis they are assigned as hypothetical proteins and their functions need to be further investigated.

As indicated by Figures 12 and 13, the Δ12/ω3 desaturase subfamily was integrated by two main groups. Group 1 included the Δ12 desaturases from Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus and Δ5 desaturase from Bacillus subtilis. In Group 2, the Δ12 desaturases of cyanobacteria and the chloroplastic Δ12 desaturases of green algae, higher plants were in the basal position, leading to Cluster 1. In Cluster 2, the microsomal Δ12 desaturases of fungi, green algae, and higher plants set apart from Δ12 desaturases of Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus, Cyanidioschyzon merolae, Ostreococcus, Thalassiosira pseudonana, and Phaeodactylum tricorutum. Cluster 3 included the ω3 desaturases of cyanobacteria at the basal position, ω3 desaturases of green algae and both microsomal and chloroplastic ω3 desaturases of higher plants. Thus, the plastidial Δ12 desaturases are ancestral to the ω3 and microsomal Δ12 desaturases, and the ω3 desaturase of higher plants and green algae arose by independent gene duplication events from prokaryotic ω3 desaturase [28].

3.4. Discovery of Candidate Genes for Δ6 Desaturases

The “front-end” desaturases (Δ4, Δ5, Δ6, and Δ8 desaturases) formed a separate clade, and their phylogeny is complicated (Figures 12 and 13). It has been speculated that front-end desaturases may have the same origin, but their precise lineages are still unclear. There were just four prokaryotic Δ6 desaturases found from cyanobacterial genomes in our analysis: Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (NP_441824), Cyanothece sp. CCY0110 (ZP_01727982), Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106 (ZP_01619238), Nodularia spumigena CCY9414 (ZP_01632618), among which the function and molecular characteristics of Δ6 acyl-lipid desaturases from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 had been fully analyzed [13].

3.5. Occurrence and Phyletic Distribution of Fatty Acid Desaturases in Thirty Seven Cyanobacteria

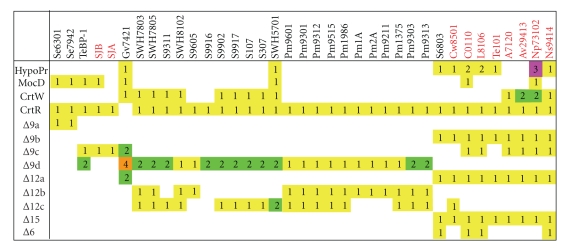

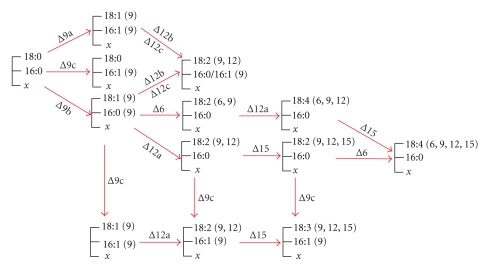

In this study, thirty one unicellular and six filamentous cyanobacterial genomes were searched by bioinformatic approach for the putative fatty acid desaturases involved in polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis. 193 protein sequences were obtained from the 37 cyanobacterial genomes, 120 of which were annotated as fatty acid desaturase. The pathway of acyl-lipid desaturation and the distribution of desaturases among different cyanobacterial species were speculated and summarized in Figures 14 and 15. Among these cyanobacteria, the Δ9 desaturase existed in 37 species of cyanobacteria. The Δ12, Δ15 and Δ6 desaturases existed in 31, 9, and 4 species of cyanobacteria, respectively. Based on functional criteria and the position of the clade integrated by Δ9 desaturases, Δ9 desaturase is assumed to be the ancestor of the remaining desaturases [28]. The functions performed by the latter three desaturases could have been obtained in some organisms along the evolutionary lineages.

Figure 14.

Diversity of different enzymes in thirty seven cyanobacteria. Distributions and amounts of different enzymes are marked by colors. One: red, two: green, three: magenta, four: orange. Names of nitrogen-fixing strains are marked in red. “HypoPr” represents hypothetical protein.

Figure 15.

The acyl-lipid desaturation of fatty acids in cyanobacteria. Numbers around arrowhead indicate the positions at which a double bond is introduced. Δ9a : desaturation occurring on both the sn-1 and the sn-2 positions of glycerolipids, Δ9b: desaturation occurring on the sn-1 position of glycerolipids, Δ9c : desaturation occurring on the sn-2 position of glycerolipids, Δ9d: genes with desaturation sn-position of glycerolipids unspecified. Δ12a : Clade 3 of Δ12 homologous genes, Δ12b: Clade 1 of Δ12 homologous genes, Δ12c : Clade 4 of Δ12 homologous genes.

Twenty seven of the investigated cyanobacteria come from the marine environment. These are 11 unicellular Prochlorococcus strains, 11 unicellular marine Synechococcus strains, Cyanothece sp. CCY0110, Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501, Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101, Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106, and Nodularia spumigena CCY9414. The other strains are from freshwater, soil, rock, hot spring, or symbiont.

In the 16S rRNA tree, marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus make a monophyletic group supported by a comparatively high-statistical confidence value, 100% (Figure 1). The two genera are proposed to diverge from a common phycobilisome-containing ancestor. While marine Synechococcus still uses phycobilisomes as light-harvesting antennae, members of the Prochlorococcus genus lack phycobilisomes and use a different antenna complex that possesses derivatives of chlorophyll a and b. They are the dominant picophytoplankton in the world’s open oceans. Carbon fixation is dominated by them and together they have been shown to contribute between 32 and 80% of the primary production in oligotrophic oceans [29–32]. Synechococcus are distributed ubiquitously throughout oceanic regions, ranging from polar through temperate to tropical waters and are generally more abundant in nutrient-rich surface waters than oligotrophic areas, whilst Prochlorococcus are largely confined to a 40°N∼40°S latitudinal band, being generally absent from brackish or well-mixed waters. Prochlorococcus also generally extend deeper in the water column than Synechococcus [33, 34].

Prochlorococcus have been divided into two genetically and physiologically distinct groups: high- and low-B/A ecotypes, which were originally named for their difference in optimal growth irradiance (low- and high-light adapted, resp.) [35, 36]. High-B/A isolates, with larger ratios of chl b/a 2, are able to grow at extremely low irradiances (less than 10 umol of quanta [Q] m−2 s−1) and preferentially thrive at the bottom of the euphotic zone (80–200 m) at dimmer light but in a nutrient-rich environment [37, 38]. Low-B/A isolates, have lower chl b/a 2 ratios, are able to grow maximally at higher light intensities, and occupy the upper, well illuminated but nutrient-poor 100-m layer of the water column [37, 38]. In the 16S rRNA tree, high-light-adapted Prochlorococcus sp. arises from a low-light-adapted clade (Figure 1). Prochlorococcus marinus strains AS9601, MIT 9312, MIT 9301, MIT 9515, and CCMP1986 belong to low-B/A ecotype. Their genome sizes vary from 1.6 Mb to 1.7 Mb, smaller than that of the low light-adapted strains (1.7 Mb to 2.6 Mb). They all contain two types of desaturases, one Δ9 desaturases and two Δ12 desaturases (b-type and c-type). Strains NATL1A, NATL2A, MIT 9211, CCMP1375, MIT 9303, and MIT 9313 belong to high-B/A ecotype. Only b-type Δ12 desaturase exists in strain NATL1A, NATL2A, and MIT 9211; while two Δ9 desaturases exist in strain MIT 9303 and MIT 9313, which have larger genome size (2.6 Mb and 2.4 Mb) compared to other high-B/A ecotypes.

The marine Synechococcus isolates have themselves been classified into three groups, designated marine cluster -A, -B, and -C (MC-A, MC-B, MC-C), based on the composition of the major light harvesting pigments, an ability to perform a novel swimming motility, whether they have an elevated salt requirement for growth, and G+C content [39]. The marine cluster A group (mol% G+C = 55–62), phycoerythrin-containing strains, has an elevated salt (Na+, Cl−, Mg2+ and Ca2+) requirement for growth and occur abundantly within the euphotic zone of both open-ocean and coastal waters [40–44]. This cluster is additionally diverse in that ratios of phycourobilin to phycoerythrobilin chromophores differ among phycoerythrins of different strains [45, 46]. The marine cluster B (mol% G+C = 63–69.5) includes halotolerant strains that possess phycocyanin but lack phycoerythrin and appear confined to coastal waters. A further cluster, marine cluster C (MC-C) has been distinguished by its low % G+C (47.5–49.5) containing strains from brackish or coastal marine waters [39]. These latter environments have been relatively poorly studied so far and are likely underrepresented in cultured Synechococcus isolates [33]. The b-type Δ12 desaturase only exists in strains WH 7803, WH 7805, WH 8102, and CC9605. Except for strains RS9916 and CC9605, other strains all contain c-type Δ12 desaturase, two copies of which exist in strain WH 5701 (MC-B) whose genome (30 Mb) is larger than other Synechococcus strains (22 Mb–26 Mb). The unique characteristics can be observed in strain RS9916 that contains only Δ9 fatty acid desaturase.

The pathway of acyl-lipid desaturation for marine cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus differs obviously from that of other cyanobacteria, indicating the different phylogenetic histories of the two genera from other cyanobacteria. At present, few fatty acid composition of these unicellular cyanobacteria has been determined yet, as functionally characterized genes. Therefore, the analysis on fatty acids in these cyanobacteria should provide more meaningful information for further research.

The two closely related freshwater Synechococcus elongatus strains PCC 6301 and PCC 7942 branch outside the marine picophytoplankton group (Figure 1), which suggests that marine cyanobacteria may diverge from the freshwater cyanobacterial ancestor. The gene arrangement and nucleotide sequence of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 6301 are nearly identical to those of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, except for the presence of a 188.6 kb inversion. Genome-wide screening only recognizes one a-type Δ9 desaturase in these two strains.

Three thermophilic unicellular strains, Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1 and two Synechococcus Yellowstone species, are most closely related to Gloeobacter violaceus sp. PCC 7421, and phylogenetically distinct from other cyanobacterial lineages (Figure 1). They were all isolated from the hot spring. Additionally, the latter two thermophilic strains are capable of N2 fixation with a diurnal rhythm. Genes for three types of fatty acid desaturases (desA, desB, and desD) are missing in contrast with mesophilic Synechocystis, although the fourth type (desC) is found in Synechococcus and Thermosynechococcus elongtus. This agrees with the absence of highly unsaturated fatty acids in lipids, which are popular in many thermophiles [47]. Synechococcus sp. JA-2-3B′a(2-13) as well as JA-3-3Ab contains one c-type Δ9 desaturase, whereas Thermosynechococcus elongtus contains three copies, one c-type and two unspecified types. At lower temperatures, cyanobacteria desaturate the fatty acids of membrane lipids to compensate for the decrease in membrane fluidity [48]. While at higher temperatures, the membrane fluidity increased, it is unnecessary to desaturate the fatty acids of membrane lipids to produce more unsaturated fatty acids. So the thermophilic strains lack highly unsaturated fatty acids in lipids and contain only one Δ9 desaturase in contrast with mesophilic strains, which probably due to their thermic habitats.

Gloeobacter violaceus sp. PCC 7421 was originally isolated from calcareous rock in Switzerland [49, 50]. It is an unusual unicellular cyanobacterium for the absence of thylakoid membranes, and its phycobilisomes and photosystem reaction centers are localized in the plasma membrane [51, 52]. It is also remarkable that Sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol (SQDG), which is thought to have an important role in photosystem stabilization, is absent in Gloeobacter while the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) is high [53]. The data of the fatty acid composition of Gloeobacter violaceus are few in number and contradictory. In one case, linoleic and α-linolenic acids were found [53]. In other work, linoleic and γ-linolenic acids were identified [54]. The occurrence of α-linolenic or γ-linolenic acid confirms that there must be a gene in the strain that is functionally similar to the ω3 desaturase or Δ6 desaturase. Two types of desaturases, six Δ9 desaturases (two c-types and four unspecified types) and two Δ12 desaturases (a-type), were recognized from this strain. One hypothetical protein (NP_923117) was also found, but the three histidine-motifs of it (HDAGH, HNQLHH, HTAHH) did not agree with the standards for a front-end or ω3 desaturase. It is this protein or another protein that performs the same function as the front-end or ω3 desaturase, which need further investigation. The types and amounts of desaturases in Gloeobacter violaceus sp. PCC 7421 are distinct to those of other cyanobacteria (Figure 14). This result may accord with the conclusion that this organism is one of the earliest ones that diverged from the cyanobacterial line [55].

Nine of the 37 cyanobacteria studied here are known to fix nitrogen (Figure 1). Four Nostocales, Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133, Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413, and Nodularia spumigena CCY9414, are heterocyst-forming filamentous diazotroph; the other five are nonheterocystous nitrogen fixers, which are filamentous strains Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101, Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106, unicellular strains Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501, Cyanothece sp. CCY0110 along with thermophic Synechococcus strains JA-2-3B′a(2-13) and JA-3-3Ab.

The diazotrophic filamentous cyanobacteria, which can form terminally differentiated, nondividing heterocysts in response to nitrogen deprivation and the ensuing intracellular accumulation of 2-oxoglutarate [56], have almost the largest genome sizes (53 Mb–90 Mb) and are isolated from soil (Anabaena PCC7120), from fresh water (Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413), from a plant-cyanobacterial symbionsis (Nostoc punctiforme PCC73102), or from the surface of Baltic sea (Nodularia spumigena CCY9414). Three types of desaturases (Δ9, Δ12, and Δ15) exist in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413, and Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133, with the exception that Nodularia spumigena CCY9414 contains four types of desaturases (Δ9, Δ12, Δ15, and Δ6). Moreover, phylogenetic analysis shows that the desaturase genes of the same type all cluster together for these four strains, indicating a recent common ancestor for Anabaena and Nostoc [57].

Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 and Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106, which belong to the Oscillatoriales, both fix N2 and do not form heterocysts (Figure 1). Trichodesmium, but not Lyngbya, is known to fix nitrogen in differentiated cells called diazocytes. Like heterocysts, diazocytes are the exclusive carriers of nitrogenase and fix nitrogen aerobically in the light, and show morphological and physiological changes [58].

Unicellular strains Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501, Cyanothece sp. CCY0110, and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 belong to the Chroococcaces (Figure 1), among which the former two strains fix nitrogen presumably at night while growing photosynthetically during the day. Three types of desaturases (Δ9, Δ12, and Δ15) exist in Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501 and Trichodesmium erythraeum, while four types of desaturases (Δ9, Δ12, Δ15, and Δ6) exist in Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106, Cyanothece sp. CCY0110 and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. It is worth noting that the c-type Δ12 desaturase is identified exclusively in Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501, which may be due to horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from marine cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus.

In conclusion, the filamentous or N2-fixing cyanobacteria usually possess more types of fatty acid desaturases than unicellular species. The main role of fatty acid desaturase of cyanobacteria is to modulate the fluidity of membranes, which helps to improve tolerance to physiological stressors such as low temperature, high light-induced photoinhibition, salt-induced damage, or desiccation. Thus, the amounts and types of fatty acid desaturases are various among different cyanobacterial species. This evolution scheme might have formed under the force adapting to distinct environments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Innovative Project of Chinese Academy of Science (KZCX2-YW-209, KZCX2-YW-216), Hi-Tech Research and Development Program (2006AA090303) of China, and the CAS/SAFEA International Partnership Program for Creative Research Teams (Research and Applications of Marine Functional Genomics). Xiaoyuan Chi and Qingli Yang contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Chapman D. Phase transitions and fluidity characteristics of lipids and cell membranes. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 1975;8(2):185–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500001797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh SC, Sinha RP, Häder DP. Role of lipids and fatty acids in stress tolerance in cyanobacteria. Acta Protozoologica. 2002;41(4):297–308. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scanlan D. Cyanobacteria: ecology, niche adaptation and genomics. Microbiology Today. 2001;28:128–130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant DA, editor. The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato N, Murata N, Miura Y, Ueta N. Effect of growth temperature on lipid and fatty acid compositions in the blue-green algae, Anabaena variabilis and Anacystis nidulans . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1979;572(1):19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato N, Murata N. Studies on the temperature shift induced desaturation of fatty acids in monogalactosyl diacylglycerol in the blue-green alga (cyanobacterium), Anabaena variabilis . Plant and Cell Physiology. 1981;22:1043–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wada H, Murata N. Temperature-induced changes in the fatty acid composition of the cyanobacterium, Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Physiology. 1990;92(4):1062–1069. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.4.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murata N, Wada H. Acyl-lipid desaturases and their importance in the tolerance and acclimatization to cold of cyanobacteria. Biochemical Journal. 1995;308(1):1–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3080001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stubbs CD, Smith AD. The modification of mammalian membrane polyunsaturated fatty acid composition in relation to membrane fluidity and function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1984;779(1):89–137. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(84)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coolbear KP, Berde CB, Keough KMW. Gel to liquid-crystalline phase transitions of aqueous dispersions of polyunsaturated mixed-acid phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry. 1983;22(6):1466–1473. doi: 10.1021/bi00275a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han T, Sinha RP, Häder DP. UV-A/blue light-induced reactivation of photosynthesis in UV-B irradiated cyanobacterium, Anabaena sp. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2001;158(11):1403–1413. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto H, Allakhverdiev SI, Inaba M, Yokota A, Murata N. Oxidative stress inhibits the repair of photodamage to the photosynthetic machinery. EMBO Journal. 2001;20(20):5587–5594. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tasaka Y, Gombos Z, Nishiyama Y, et al. Targeted mutagenesis of acyl-lipid desaturases in Synechocystis: evidence for the important roles of polyunsaturated membrane lipids in growth, respiration and photosynthesis. EMBO Journal. 1996;15(23):6416–6425. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gombos Z, Kanervo E, Tsvetkova N, Sakamoto T, Aro E-M, Murata N. Genetic enhancement of the ability to tolerate photoinhibition by introduction of unsaturated bonds into membrane glycerolipids. Plant Physiology. 1997;115(2):551–559. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murata N, Wada H, Gombos Z. Modes of fatty-acid desaturation in cyanobacteria. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1992;33:933–941. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, et al. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Research. 1996;3(3):109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chintalapati S, Prakash JSS, Gupta P, et al. A novel Δ9 acyl-lipid desaturase, DesC2, from cyanobacteria acts on fatty acids esterified to the sn-2 position of glycerolipids. Biochemical Journal. 2006;398(2):207–214. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards DJ, Marquez BL, Nogle LM, et al. Structure and biosynthesis of the jamaicamides, new mixed polyketide-peptide neurotoxins from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula . Chemistry & Biology. 2004;11(6):817–833. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanklin J, Cahoon EB. Desaturation and related modifications of fatty acids. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 1998;49:611–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broadwater JA, Whittle E, Shanklin J. Desaturation and hydroxylation. Residues 148 and 324 of Arabidopsis FAD2, in addition to substrate chain length, exert a major influence in partitioning of catalytic specificity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(18):15613–15620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M, Lenman M, Banaś A, et al. Identification of non-heme diiron proteins that catalyze triple bond and epoxy group formation. Science. 1998;280(5365):915–918. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Loo FJ, Fox BG, Somerville C. Unusual fatty acids. In: Moore TS, editor. Lipid Metabolism in Plants. BocaRaton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 91–126. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanklin J, Achim C, Schmidt H, Fox BG, Münck E. Mössbauer studies of alkane ω-hydroxylase: evidence for a diiron cluster in an integral-membrane enzyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(7):2981–2986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domergue F, Spiekermann P, Lerchl J, et al. New insight into Phaeodactylum tricornutum fatty acid metabolism. Cloning and functional characterization of plastidial and microsomal Δ12-fatty acid desaturases. Plant Physiology. 2003;131(4):1648–1660. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aguilar PS, Cronan JE, Jr., De Mendoza D. A Bacillus subtilis gene induced by cold shock encodes a membrane phospholipid desaturase. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180(8):2194–2200. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2194-2200.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López Alonso D, García-Maroto F, Rodríguez-Ruiz J, Garrido JA, Vilches MA. Evolution of the membrane-bound fatty acid desaturases. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2003;31(10):1111–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goericke R, Welschmeyer NA. The marine prochlorophyte Prochlorococcus contributes significantly to phytoplankton biomass and primary production in the Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Research Part I. 1993;40(11-12):2283–2294. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li WK. Composition of ultraphytoplankton in the central north Atlantic. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1995;122(1–3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Nolla HA, Campbell L. Prochlorococcus growth rate and contribution to primary production in the equatorial and subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 1997;12(1):39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veldhuis MJW, Kraay GW, Van Bleijswijk JDL, Baars MA. Seasonal and spatial variability in phytoplankton biomass, productivity and growth in the northwestern Indian ocean: the southwest and northeast monsoon, 1992-1993. Deep Sea Research Part I. 1997;44(3):425–449. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scanlan DJ, West NJ. Molecular ecology of the marine cyanobacterial genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus . FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2002;40(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Partensky F, Hess WR, Vaulot D. Prochlorococcus, a marine photosynthetic prokaryote of global significance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 1999;63(1):106–127. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.106-127.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocap G, Moore LR, Chisholm SW. Molecular phylogeny of Prochlorococcus ecotypes. In: Charpy L, Larkum AWD, editors. Marine Cyanobacteria. Monaco, France: Bulletin de l'Institut Océanographique; 1999. pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore LR, Rocap G, Chisholm SW. Physiology and molecular phytogeny of coexisting Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Nature. 1998;393(6684):464–467. doi: 10.1038/30965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore LR, Chisholm SW. Photophysiology of the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus: ecotypic differences among cultured isolates. Limnology and Oceanography. 1999;44(3):628–638. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dufresne A, Salanoubat M, Partensky F, et al. Genome sequence of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus SS120, a nearly minimal oxyphototrophic genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(17):10020–10025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733211100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waterbury JB, Rippka R. Subsection 1. Order Croococcales Wettsten 1924, emend. Rippka et al., 1979. In: Staley JT, Bryant MP, Pfenning N, Holt JG, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 3. Baltimore, Md, USA: Williams and Wilkins; 1989. pp. 1728–1746. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferris MJ, Palenik B. Niche adaptation in ocean cyanobacteria. Nature. 1998;396(6708):226–228. [Google Scholar]