Abstract

This paper introduces a simple chemical model of a β-sheet (artificial β-sheet) that dimerizes by parallel β-sheet formation in chloroform solution. The artificial β-sheet consists of two N-terminally linked peptide strands that are linked with succinic or fumaric acid and blocked along one edge with a hydrogen-bonding template composed of 5-aminoanisic acid hydrazide. The template is connected to one of the peptide strands by a turn unit composed of (S)-2-aminoadipic acid (Aaa). 1H NMR spectroscopic studies show that these artificial β-sheets fold in CDCl3 solution to form well-defined β-sheet structures that dimerize through parallel β-sheet interactions. Most notably, all of these compounds show a rich network of NOEs associated with folding and dimerization. The compounds also exhibit chemical shifts and coupling constants consistent with the formation of folded dimeric β-sheet structures. The aminoadipic acid unit shows patterns of NOEs and coupling constants consistent with a well-defined turn conformation. The present system represents a significant step toward modeling the type of parallel β-sheet interactions that occur in protein aggregation.

Introduction

The formation of parallel β-sheets through intermolecular interaction between polypeptide strands has emerged as a central problem in protein aggregation associated with Alzheimer’s disease, the prion diseases, and other neurodegenerative disorders. Recent studies have established that β-amyloid peptides, associated with Alzheimer’s disease, aggregate through parallel β-sheet interactions.1 Parallel β-sheet organization has also been found in infectious prion proteins,2 as well as in model peptides of the yeast amyloid protein Sup35p.3 X-ray crystallographic studies of various other small model amyloidogenic peptides have shown both parallel and antiparallel β-sheet structures. 4

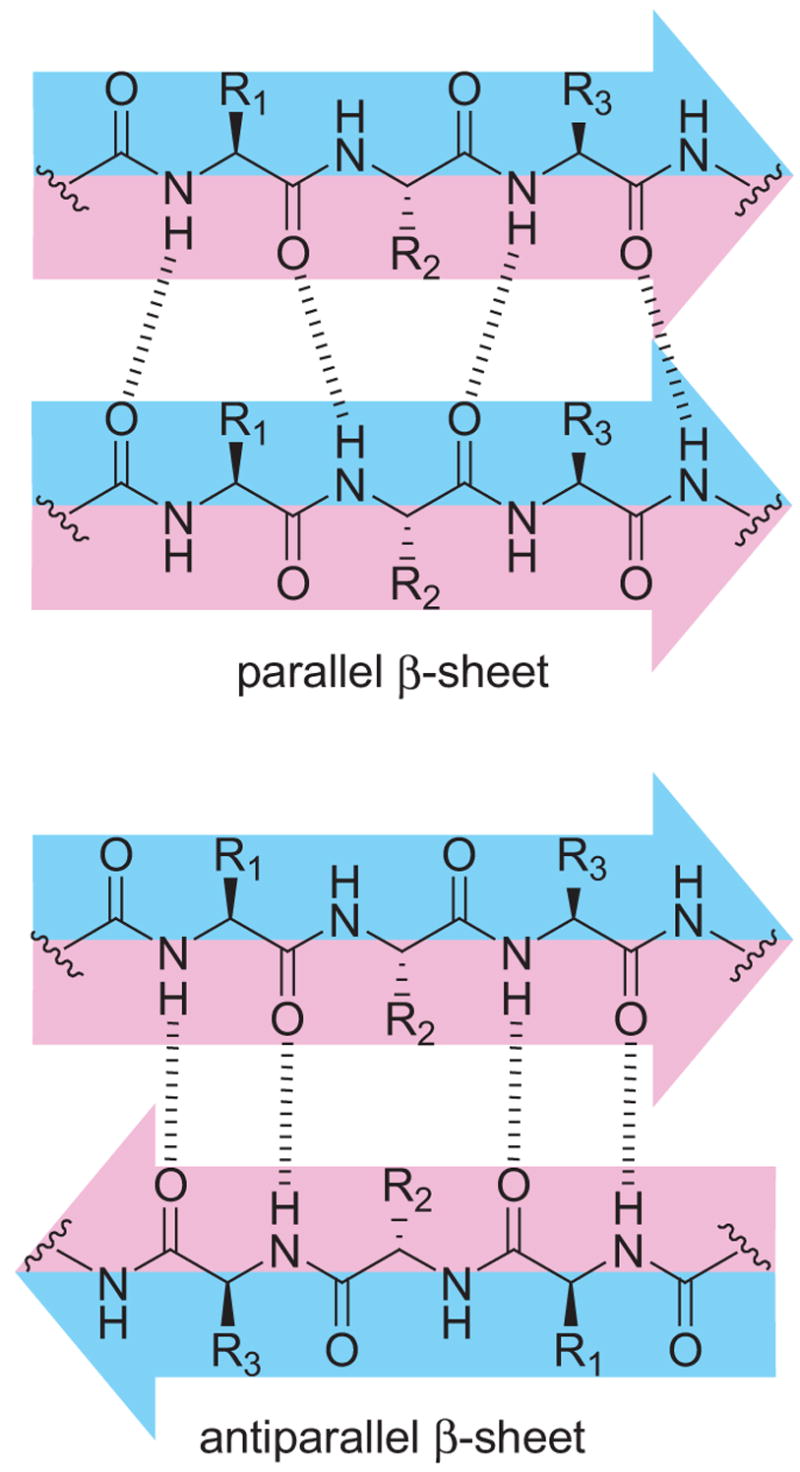

The formation of parallel β-sheets through in-register interaction of like peptide strands constitutes a special type of molecular recognition that does not occur in antiparallel β-sheets. When parallel β-sheets form in peptide and protein aggregation, like side chains (e.g., R1, R2, and R3 in Chart 1) align in stripes across the faces of the β-sheets. The side chains can adopt the same torsion angles (χ1, χ2, etc.) and thus pack together like forks, spoons, and, knives in a silverware drawer.

Chart 1.

Peptide and protein aggregates cannot generally be studied by standard solution-phase techniques (e.g., solution-phase NMR spectroscopy), because they are generally not soluble. Chemical model systems provide an attractive tool for simplifying the aggregation problem to a single set of interactions. Antiparallel β-sheet formation has been studied heavily using β-hairpin model systems.5 β-Hairpins provide a natural intramolecular model for antiparallel β-sheet formation, because a β-turn allows a peptide to fold back on itself. Parallel β-sheet formation has also been studied using hairpin-like systems containing prosthetic turn units to C- or N-terminally link two peptide strands.6,7

Our research group has previously reported model systems that use a combination of molecular templates and α-amino acids to study intermolecular antiparallel β-sheet interactions that occur upon dimer formation.8 Few other examples of model systems that dimerize through intermolecular β-sheet interactions are known.9 The only system of which we are aware that dimerizes through parallel β-sheet interactions is a macrocyclic peptide with alternating D- and L-amino acids that lacks an extended peptide strand.10 Using principles we have learned from our antiparallel dimerization model system, we set out to develop a system that dimerizes through parallel β-sheet interactions.11 Here, we introduce a simple chemical model of a β-sheet (artificial β-sheet 1) that dimerizes by parallel β-sheet formation in chloroform solution.

Results and Discussion

Chemical models of parallel β-sheets are harder to create than chemical models of antiparallel β-sheets for two reasons, one of which is obvious and the other of which is not. In intramolecular systems, antiparallel β-hairpin formation is natural to the topology of peptide strands, while the creation of a parallel analogue of a β-hairpin requires a suitable adapter unit. In intermolecular systems, antiparallel homodimeric structures can form by interaction of like edges of peptide strands, while parallel homodimeric structures require interaction of opposite edges (Chart 1). As a result of this difference, a simple chemical model that forms antiparallel β-sheets through intermolecular interaction can consist of a single peptide strand in which one edge is blocked,8 while a simple chemical model that forms parallel β-sheets through intermolecular interaction cannot.

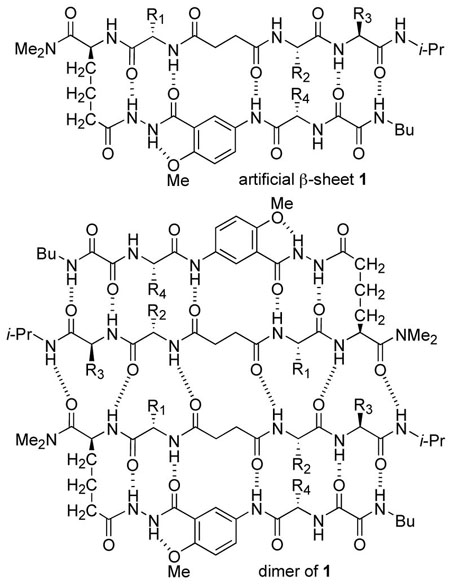

Artificial β-sheet 1 consists of two N-terminally linked dipeptide strands that are blocked along one edge. The peptides are linked with succinic acid and blocked along one edge with a hydrogen-bonding template composed of 5-aminoanisic acid hydrazide.12 The template is connected to one of the peptide strands by a turn unit composed of (S)-2-aminoadipic acid (Aaa). The other edge of each dipeptide presents three hydrogen-bonding groups. The linked dipeptides can dimerize through parallel β-sheet interactions to form six hydrogen bonds, but can only form four hydrogen bonds through antiparallel β-sheet interactions. We selected hydrophobic amino acids to allow studies in chloroform and other non-competitive solvents, and we prepared six variants (1a-f) containing Leu, Val, Ile, Ala, and Phe at the four variable sites in the molecule (AA1-AA4). Table 1 summarizes the structures of the variants. We also prepared a variant of 1f with fumaric acid in place of succinic acid (2a).

Table 1.

Artificial β-Sheets 1a-f and 2a

| compd | AA1 | AA2 | AA3 | AA4 | linker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Leu | Leu | Ile | Val | succinic acid |

| 1b | Leu | Leu | Leu | Val | succinic acid |

| 1c | Leu | Ala | Leu | Ala | succinic acid |

| 1d | Leu | Leu | Leu | Ala | succinic acid |

| 1e | Phe | Leu | Ile | Ala | succinic acid |

| 1f | Leu | Phe | Leu | Ala | succinic acid |

| 2a | Leu | Phe | Leu | Ala | fumaric acid |

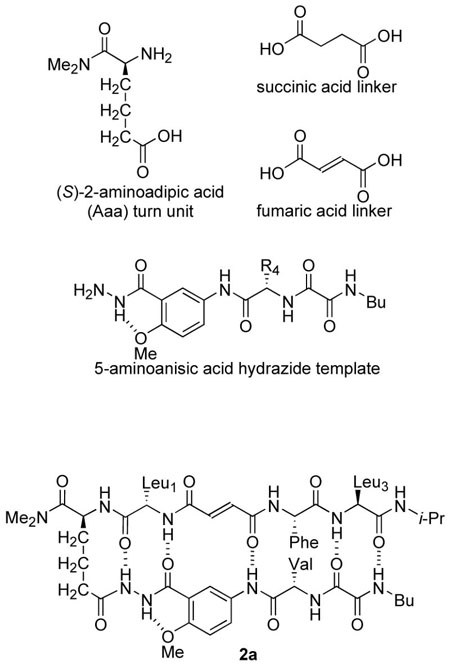

Artificial β-sheets 1a-f were assembled from these components using standard solution-phase peptide synthesis techniques (Scheme 1). The 5-aminoanisic acid hydrazide template was prepared as the TFA salt (8) from aniline 3.12b Aniline 3 was coupled with Cbz-protected valine or alanine, the resulting anilide (4, not shown) was deprotected by hydrogenolysis, and the resulting amine (5, not shown) was coupled with ethyl oxalyl chloride to yield ethyl ester 6. Aminolysis of ethyl ester 6 with butylamine, followed by treatment of the resulting butylamide (7, not shown) with trifluoroacetic acid yielded salt 8. Salt 8 was coupled with the N-Boc-5-oxazolidinone derivative of aminoadipic acid using HCTU and 2,4,6-collidine. The use of 2,4,6-collidine in this step is important; substantial double acylation of the terminal hydrazide nitrogen occurred when a stronger base (DIPEA) was used. Aminolysis of the coupling product (9, not shown) with dimethylamine, followed by removal of the resulting hydroxymethyl group and the Boc group, yielded salt 10. Coupling of salt 10 to Boc-protected amino acid Boc-AA1-OH, followed by removal of the Boc group and subsequent coupling to succinic dipeptide HO2CCH2CH2CO-AA2-AA3-NH-i-Pr yielded artificial β-sheets 1. Artificial β-sheet 2a was prepared in an analogous fashion using fumaric dipeptide HO2CCH=CHCO-Phe-Leu-NH-i-Pr.13

Scheme 1.

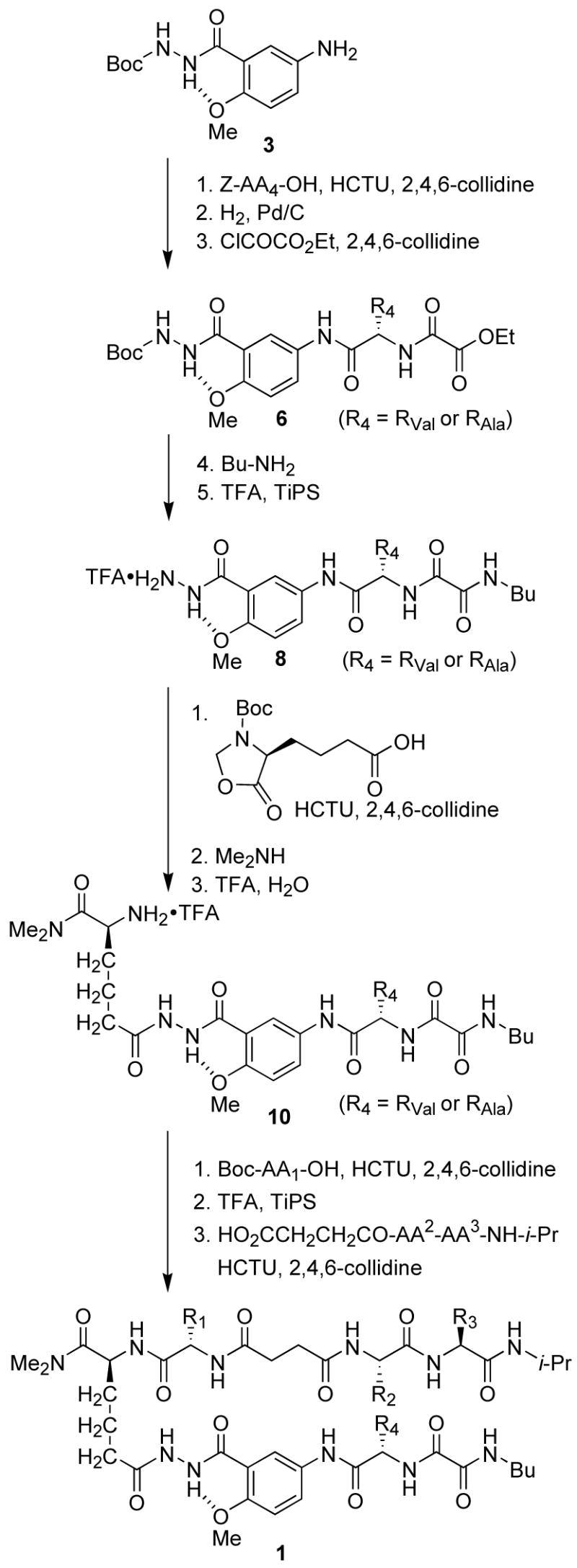

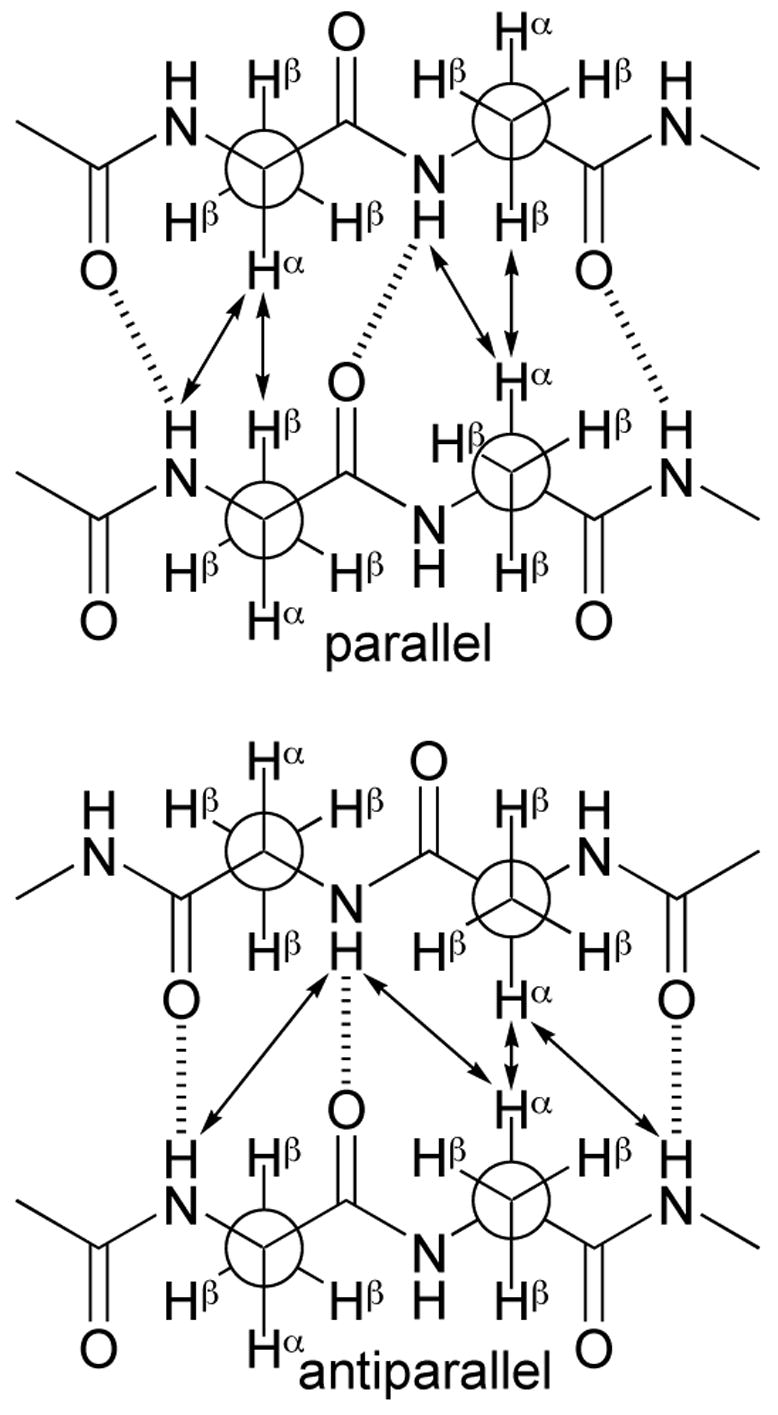

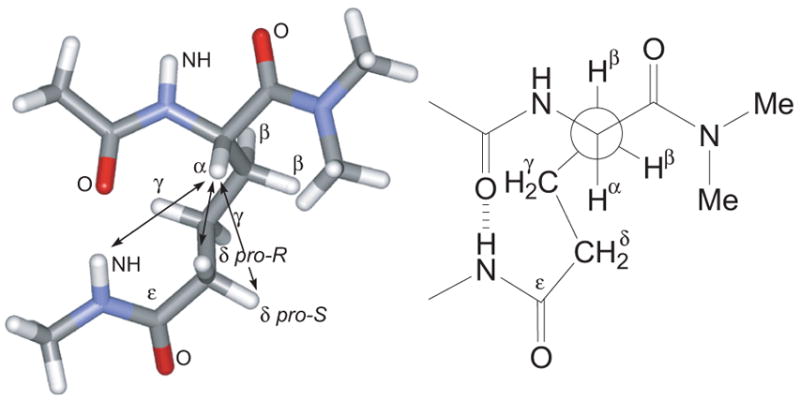

1H NMR spectroscopic studies in CDCl3 solution show that artificial β-sheets 1 and 2a form folded well-defined β-sheet structures that are dimerized through parallel β-sheet interactions. Most notably, all of these compounds show a rich network of NOEs associated with folding and dimerization. Parallel and antiparallel β-sheets have different geometrical arrangements of protons and thus show different characteristic NOEs. Figure 1 illustrates NOEs expected for parallel and antiparallel β-sheets. Antiparallel β-sheets typically give strong interstrand Hα–Hα NOEs, and weaker interstrand NH–NH and Hα–NH NOEs. Parallel β-sheets typically give strong interstrand Hα–Hβ NOEs and strong interstrand Hα–NH NOEs.

Figure 1.

Characteristic NOEs (arrows) in parallel and antiparallel β-sheets. Structures are shown for the alanine dipeptide, with Newman projections shown for the Cβ;–Cα bonds.

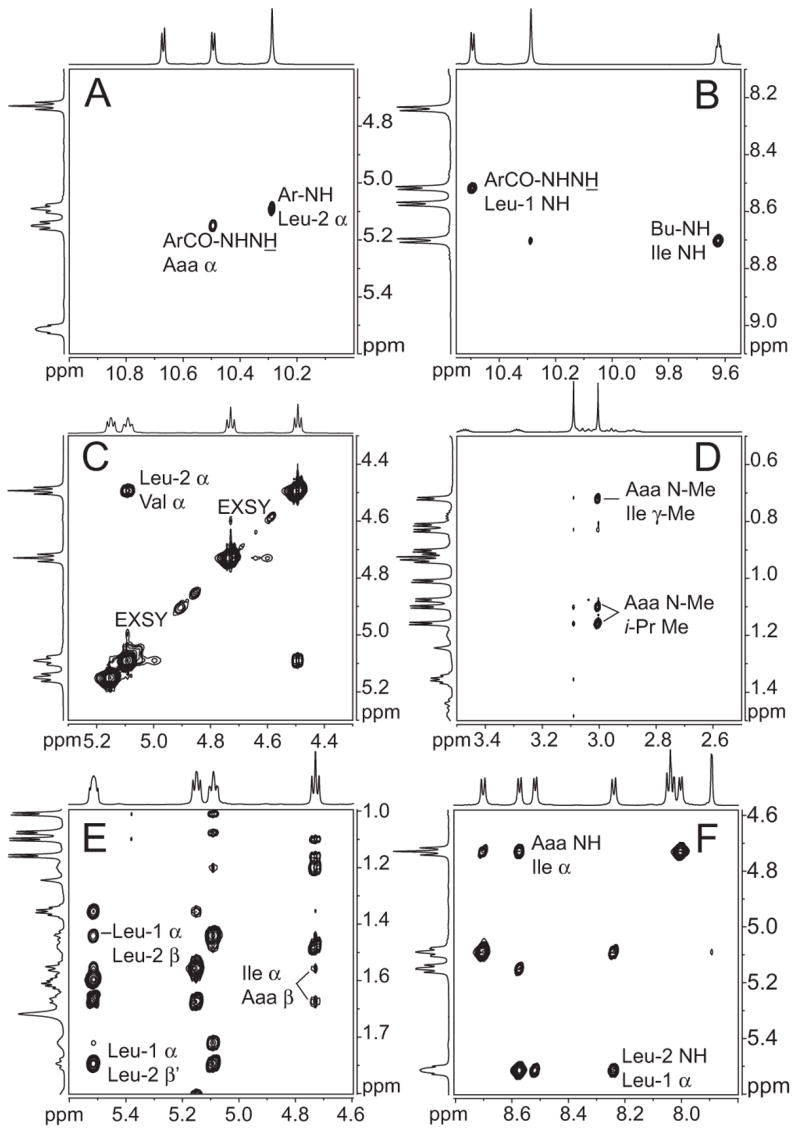

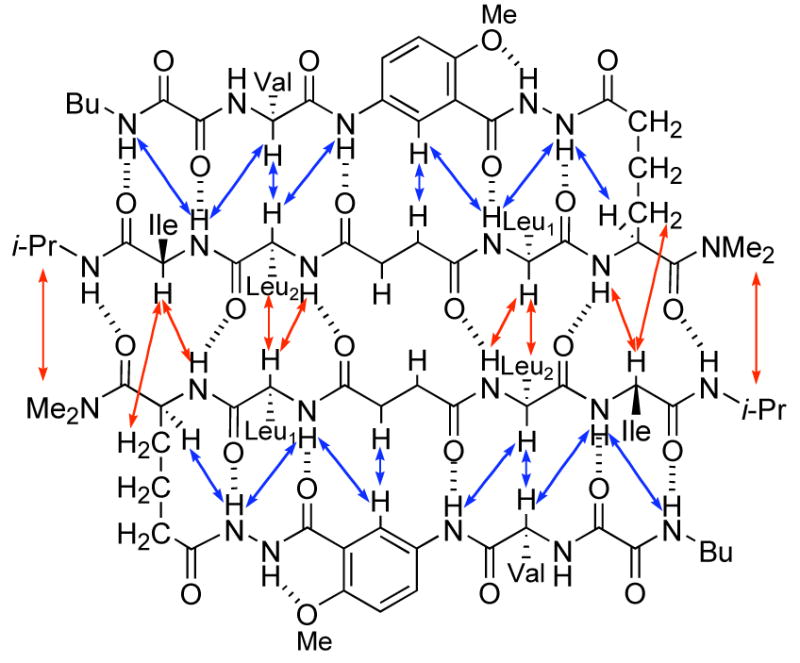

Compounds 1 and 2a show these and other NOEs consistent with antiparallel β-sheet folding and parallel β-sheet dimerization. The 1H NMR spectra of compounds 1 and 2a have good dispersion of the proton signals associated with the characteristic NOEs. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate key NOEs observed in compound 1a. The intramolecular NOEs associated with folding (Figure 3, blue arrows) are characteristic of antiparallel β-sheet formation, while the intermolecular NOEs associated with dimerization (Figure 3, red arrows) are characteristic of parallel β-sheet formation. Figure 2C shows a strong intramolecular interstrand Hα–Hα NOE. Figures 2E and 2F show strong intermolecular interstrand Hα–Hβ and Hα–NH NOEs.14,15

Figure 2.

Selected NOEs in artificial β-sheet 1a. 800-MHz NOESY spectrum recorded at 10 mM and 268 K in CDCl3 with a 400-ms mixing time. Expansions A–C show intramolecular NOEs; expansions D–F show intermolecular NOEs.14,15

Figure 3.

Key NOEs observed in artificial β-sheet 1a. Red arrows represent intermolecular NOEs; blue arrows represent intramolecular NOEs.

Consistent with the formation of hydrogen-bonded dimeric β-sheet structures, the peptide NH resonances of 1 appear downfield (7.93–8.80 ppm, Table 2). The amide proton of AA4 shows downfield shifting (7.93–8.06 ppm), even though it does not participate in interstrand or intersheet hydrogen bonding, because it is flanked by two carbonyl groups.8b Also consistent with β-sheet structure, all peptidic NH signals show large coupling constants (7.0–10.4 Hz, Table 3). The amide signals of AA3 are the most downfield (8.60–8.80 ppm) among the amino acid NH signals and the coupling constants are the largest (9.7–10.4 Hz), suggesting that the open end of the hairpin is especially well folded. The amino acid α-proton resonances of 1 appear downfield (4.46–5.94 ppm), further reflecting the formation β-sheet structure.16 The peptide resonances and coupling constants of 2a are similar to those of 1, with the exception of the NH resonance of Phe2, which appears exceptionally far downfield (9.20 ppm). The downfield shifting of this resonance may reflect subtle differences between 1 and 2a in conformation, magnetic anisotropy, or hydrogen bonding.

Table 2.

Chemical Shifts of NH Protons in CDCl3a

| compd | Aaa | AA1 | AA2 | AA3 | AA4 | ArNH | ArCO-NHNH | ArCO-NHNH | BuNH | i-PrNH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 8.57 | 8.52 | 8.24 | 8.70 | 8.05 | 10.29 | 10.67 | 10.49 | 9.62 | 8.00 |

| 1b | 8.67 | 8.47 | 8.25 | 8.68 | 8.04 | 10.28 | 10.59 | 10.44 | 9.54 | 8.03 |

| 1c | 8.37 | 8.40 | 8.42 | 8.60 | 8.00 | 10.19 | 10.71 | 10.50 | 9.50 | 8.00 |

| 1d | 8.67 | 8.39 | 8.31 | 8.69 | 7.98 | 10.20 | 10.57 | 10.43 | 9.52 | 8.03 |

| 1e | 8.01 | 8.66 | 8.23 | 8.78 | 7.93 | 10.20 | 10.69 | 10.63 | 9.65 | 8.06 |

| 1f | 8.50 | 8.41 | 8.55 | 8.80 | 8.06 | 10.09 | 10.58 | 10.40 | 9.55 | 8.06 |

| 2a | 8.77 | 8.55 | 9.20 | 8.74 | 8.05 | 10.20 | 10.45 | 10.33 | 9.53 | 8.10 |

Spectra were recorded at 1–20 mM and 268 K. Compound 1a shows no significant differences in the 1H NMR spectra from 0.02 to 10 mM.

Table 3.

Amide and Hydrazide Proton Coupling Constants

| compd | Aaa | AA1 | AA2 | AA3 | AA4 | ArCO-NHNH | ArCO-NHNH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 8.4 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| 1b | 9.1 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 8.7 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| 1c | -a | -a | -a | -a | -a | -a | -a |

| 1d | 8.7 | 8.0 | 9.2 | 10.0 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| 1e | 8.0 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 | -b | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| 1f | 8.4 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 9.7 | -b | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| 2a | 8.2 | 8.2 | 9.8 | -a | -a | -a | -a |

Coupling constant could not be determined, because the NH resonance was broad.

Coupling constant could not be determined, because the NH resonance overlapped with another signal.

The non-peptidic NH signals of artificial β-sheets 1 appear even further downfield. The anilide proton signals appear at 10.09–10.20 ppm in 1a-1f. The butyloxalamide NH proton signals appear exceptionally far downfield (9.50–9.65) ppm, further suggesting a tight hydrogen bond at the open end of the hairpin.17 The hydrazide proton signals appear the most downfield (10.40–10.71 ppm). The ArCO-NHNH hydrazide resonance (10.40–10.63 ppm) is not as far downfield as that of a related hydrogen-bonded system (11.77 ppm),8c suggesting that the turn unit does not achieve optimal geometry for hairpin formation. Each hydrazide signal appears as a doublet with a coupling constant of 7.4–7.7 Hz, suggesting an anti conformation of the hydrazide unit.

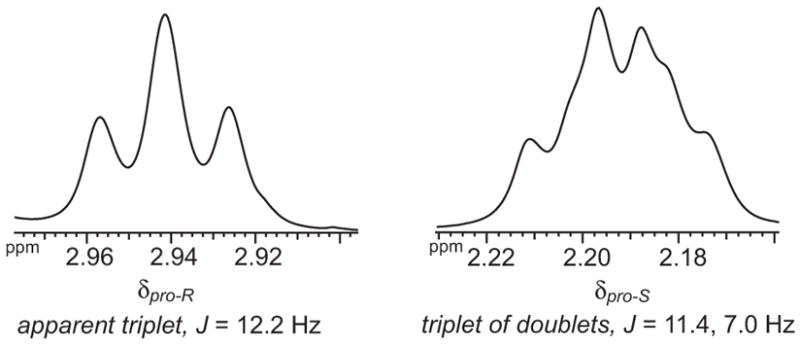

The aminoadipic acid unit shows patterns of NOEs and coupling constants consistent with a well-defined turn conformation. The aminoadipic acid α-protons of 1 and 2a give strong NOEs to the side-chain δ-protons and ε-NH proton. The α-protons show one large (ca. 12 Hz) Hα–Hβ coupling constant; the other Hα–Hβ coupling is too small to measure (ca. 1 Hz). The diastereotopic δ-protons show significant anisotropy (0.65–0.76 ppm), indicating that they reside in very different magnetic environments. They also exhibit widely different coupling patterns, with the δpro-S-proton resonance resembling a triplet of doublets with two large (11–12 Hz) coupling constants and one smaller (ca. 7 Hz) coupling constant, and δpro-R-proton resonance resembling a triplet with two large (ca. 12 Hz) coupling constants. Figure 4 shows representative splitting patterns for these protons.

Figure 4.

Representative splitting patterns for the aminoadipic acid δ-protons (artificial β-sheet 1c).

Molecular modeling of model compound Ac-Aaa(NHMe)-NMe2 provides a minimum-energy structure of the aminoadipic acid turn unit consistent with these data (Figure 5). The global minimum of the model compound was determined using MacroModel v8.5 with the MMFF* force field and GB/SA CHCl3 solvation. In this structure, the side-chain amide NH is hydrogen bonded to the main-chain acetamide carbonyl to form a hydrogen-bonded ten-membered ring. Molecular modeling indicates that this conformer is strongly preferred; the next higher-energy conformer is 2.2 kcal/mol above the global minimum. This conformer has a different conformation of the aminoadipic acid side chain but preserves the hydrogen-bonded ten-membered ring.

Figure 5.

Model of the aminoadipic acid turn unit. The global minimum of Ac-Aaa(NHMe)-NMe2 was determined using MacroModel v8.5 with the MMFF* force field and GB/SA CHCl3 solvation. Arrows indicate key NOEs observed for the turn units of 1 and 2a.

In the minimum-energy structure, the aminoadipic acid α-proton is close to the aminoadipic acid ε-NH proton (3.5 Å), δpro-S-proton (3.4 Å), and δpro-R-proton (2.2 Å). Karplus analysis provides coupling constants consistent with those observed for compounds 1 and 2a. The structure has a 294° N–Cα–Cβ–Cγ(χ1) torsion angle, which should give one large Hα–Hβ coupling constant and one small Hα–Hβ coupling constant (ca. 11 and 2 Hz).18 The structure has a 166° Cβ–Cγ–Cδ–Cε (χ3) torsion angle, which should give large and small (ca. 13 and 1 Hz) vicinal couplings for the δpro-R-proton and large and medium (ca. 12 and 6 Hz) vicinal couplings for the δpro-S-proton.18 The calculated values match the observed values well if the geminal coupling constant for the δ-protons is taken to be 12 Hz.

The succinic acid linker unit shows 1H–1H coupling patterns consistent with an extended zigzag conformation. Although the succinic acid proton resonances overlap heavily with other signals, we were able to extract coupling constants from all four succinic acid resonances of 1a. Two of the resonances are distinct doublet of doublet of doublets (J = 17.1, 13.0, 5.7 Hz). The other two resonances overlap heavily with other signals, but can be resolved by resolution enhancement into two overlapping doublet of doublet of doublets (J = 17.1, 13.1 Hz, 3.0 Hz).19,20 These coupling constants reflect that each proton experiences one geminal coupling, one anti vicinal coupling, and one gauche vicinal coupling. If the C(O)–CH2–CH2–C(O) torsion angle were perfectly 180°, all four succinic proton signals should exhibit identical patterns of doublet of doublet of doublets with a geminal coupling of ca. 17 Hz,21 an anti vicinal coupling of ca. 14 Hz, and a gauche vicinal coupling of ca. 3 Hz.18 The slight mismatch between the observed and ideal coupling patterns might reflect slight deviation from a perfect zigzag conformation. The presence of large (ca. 13 Hz) vicinal coupling constants in all four resonances indicates that there is no significant population of gauche conformer.

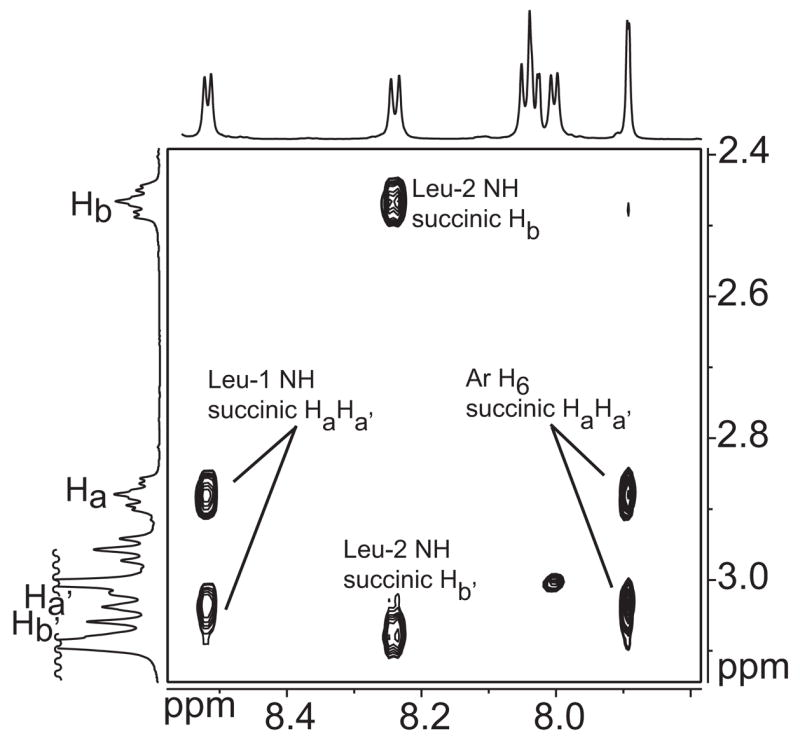

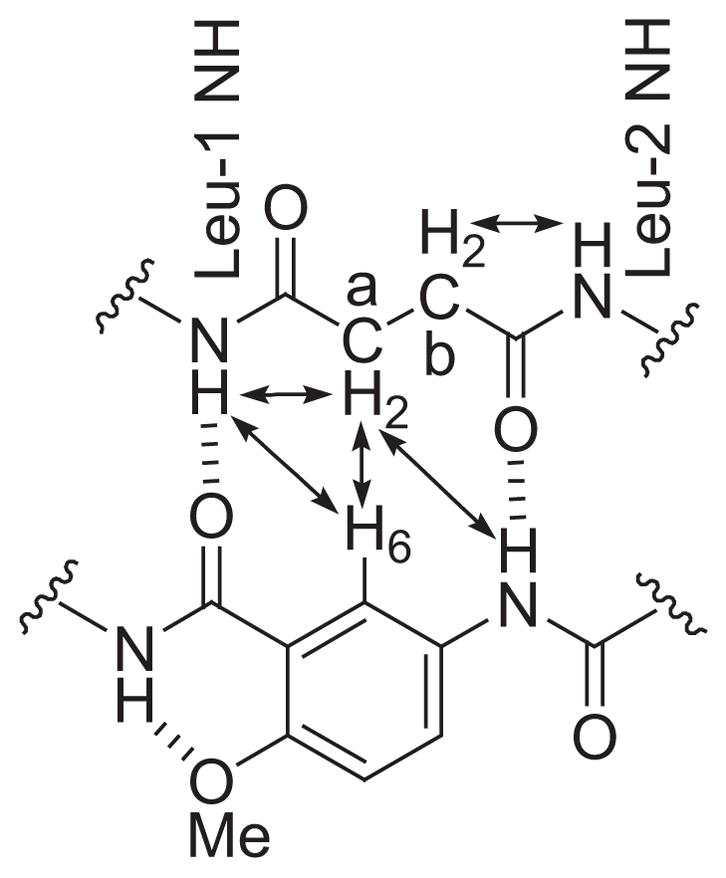

Intramolecular NOEs provide additional support for the extended conformation of the succinic acid linker unit (Figure 6). One diastereotopic pair of succinic acid protons in 1a (Ha and Ha′) give NOEs to the Leu-1 NH proton and to the proton at the 6-position of the aromatic ring; the other pair (Hb and Hb′) give NOEs to the Leu-2 NH proton.22 Chart 2 illustrates NOEs observed for each pair of protons and shows the extended zigzag conformation of the succinic acid linker unit.

Figure 6.

Selected NOEs observed for the succinic acid protons of 1a. 800-MHz NOESY spectrum recorded at 10 mM and 268 K in CDCl3 with a 400-ms mixing time.

Chart 2.

Key NOEs observed for the succinic acid linker unit of 1a.

Conclusion

N-Terminally linking two peptide strands and blocking one edge of the resulting linked dipeptide creates a peptide system that dimerizes through parallel β-sheet formation. Linking two dipeptides with a diacid unit maximizes the number of hydrogen-bonding groups available for dimerization through parallel β-sheet interactions and minimizes the number of hydrogen-bonding groups available for the dimerization through antiparallel β-sheet interactions. Either succinic acid or fumaric acid works as a linker; we prefer the former, because the succinic acid compounds are slightly easier to prepare.23 Blocking one edge of the peptides with a molecular template prevents uncontrolled oligomerization. A turn unit based on (S)-2-aminoadipic acid adopts a well-defined conformation with an intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded ten-membered ring and promotes folding between the peptide strand and the molecular template.

The present system represents a significant step toward modeling the type of parallel β-sheet interactions that occur in protein aggregation. Although the system dimerizes in chloroform, not in water, it achieves intermolecular parallel β-sheet interactions, which are simply not achieved by any other model system. Our research group previously developed a related intermolecular model system for antiparallel β-sheet formation in chloroform solution.8c Using that system, we were able to explore side chain interactions in intermolecular antiparallel β-sheet systems.8d–f,24 We then extended this system to water thorough judicious use of macrocyclization and hydrophobic interactions.8g We anticipate being able to use similar strategies to study intermolecular side chain interactions in parallel β-sheets and to extend the current system to aqueous solution.7 We will report these efforts when they come to fruition.

Supplementary Material

Synthetic procedures and NMR spectroscopic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NSF (CHE-0213533) and NIH (GM-49076) for grant support and Dr. Bao Nguyen for help with collecting 800-MHz NMR data.

References and Notes

- 1.(a) Petkova TA, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Döbeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritter C, Maddelein ML, Siemer AB, Lührs T, Ernst M, Meier BH, Saupe SJ, Riek R. Nature. 2005;435:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nature03793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shewmaker F, Wickner RB, Tycko R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19754–19759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609638103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Balbirnie M, Madsen AØ, Riekel C, Grothe R, Eisenberg D. Nature. 2005;435:773–778. doi: 10.1038/nature03680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sawaya MR, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, Ivanova MI, Sievers SA, Apostol MI, Thompson MJ, Balbirnie M, Wiltzius JJW, MacFarlane HT, Madsen AØ, Riekel C, Eisenberg D. Nature. 2007;447:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Syud FA, Stanger HE, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8667–8677. 1. doi: 10.1021/ja0109803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Russell SJ, Blandl T, Skelton NJ, Cochran AG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:388–395. doi: 10.1021/ja028075l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nowick JS, Brower JO. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:876–877. doi: 10.1021/ja028938a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ciani B, Jourdan M, Searle MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9038–9047. doi: 10.1021/ja030074l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Aemissegger A, Krautler V, van Gunsteren WF, Hilvert D. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2929–2936. doi: 10.1021/ja0442567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hughes RM, Waters ML. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6518–6519. doi: 10.1021/ja0507259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Mahalakshmi R, Raghothama S, Balaram P. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1125–1138. doi: 10.1021/ja054040k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Hughes RM, Waters ML. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13586–13591. doi: 10.1021/ja0648460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Nowick JS, Smith EM, Noronha G. J Org Chem. 1995;60:7386–7387. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nowick JS, Insaf S. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:10903–10908. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chitnumsub P, Fiori WR, Lashuel HA, Diaz H, Kelly JW. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:39–59. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fisk JD, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:343–344. doi: 10.1021/ja002493d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fisk JD, Schmitt MA, Gellman SH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7148–7149. doi: 10.1021/ja060942p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The use of chemical model systems to study protein folding and interactions provides a complementary approach to the empirical or statistical study of whole proteins. For some leading examples of studies of interactions within parallel β-sheets, see: Lifson S, Sander C. J Mol Biol. 1980;139:627–639. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90052-2.Merkel JS, Sturtevant JM, Regan L. Structure. 1999;7:1333–1343. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80023-4.Steward RE, Thornton JM. Proteins. 2002;48:178–191. doi: 10.1002/prot.10152.Distefano MD, Zhong A, Cochran AG. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00738-6.Fooks HM, Martin ACR, Woolfson DN, Sessions RB, Hutchinson EG. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.008.

- 8.(a) Nowick JS, Tsai JH, Bui QCD, Maitra S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8409–8410. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nowick JS, Chung DM, Maitra K, Maitra S, Stigers KD, Sun Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7654–7661. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nowick JS, Lam KS, Khasanova TV, Kemnitzer WE, Maitra S, Mee HT, Liu R. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4972–4973. doi: 10.1021/ja025699i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nowick JS, Chung DM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:1765–1768. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chung DM, Nowick JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3062–3063. doi: 10.1021/ja031632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chung DM, Dou Y, Baldi P, Nowick JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9998–9999. doi: 10.1021/ja052351p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Khakshoor O, Demeler B, Nowick JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5558–5569. doi: 10.1021/ja068511u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Gong B, Yan Y, Zeng H, Skrzypczak-Jankunn E, Kim YW, Zhu J, Ickes H. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5607–5608. [Google Scholar]; (b) Phillips ST, Rezac M, Abel U, Kossenjans M, Bartlett PA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:58–66. doi: 10.1021/ja0168460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghadiri MR, Kobayashi K, Granja JR, Chadha RK, McRee DE. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Nowick JS. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:287–296. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nowick JS. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:3869–3885. doi: 10.1039/b608953b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Nowick JS, Pairish M, Lee IQ, Holmes DL, Ziller JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5413–5424. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsai JH, Waldman AS, Nowick JS. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A second homologue with the fumaric acid linker (2b: R1 = RPhe, R2 = RPhe; R3 = RIle; R4 = RAla) exhibits a complicated 1H NMR spectrum in CDCl3 solution, suggesting multiple conformers and/or oligomers.

- 14.1H NMR titration studies of 1a show no significant changes in the 1H NMR spectra from 0.02 to 10 mM in CDCl3 solution at 268 K. No significant differences are observed between the NOESY spectra of 1a at 0.5 mM and 10 mM in CDCl3, except for a higher noise level at the lower concentration. These experiments show no evidence of unfolded or monomeric structures at these concentrations and suggest that the dimer association constant is greater than 106 M−1.

- 15.Although 1H NMR spectra of compounds 1 and 2a are largely homogenous, there are some EXSY cross-peaks in NOESY and ROESY spectra. In the 1-D 1H NMR spectrum of compound 1a, two sets of minor peaks (2% and 4%) that correlate with these cross-peaks are present. These peaks suggest the formation of minor (2% and 4%) conformers or oligomers with alternative hydrogen-bonding patterns.

- 16.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1647–1651. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The butyloxalamide NH signals appear at ca. 8.90 ppm in CD3SOCD3.

- 18.Haasnoot CAG, de Leeuw FAAM, Altona C. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:2783–2792. as implemented in MacroModel. [Google Scholar]

- 19.A Lorentz-Gauss transformation was used to enhance resolution (lb = −1.0 Hz, gb = 0.2).

- 20.The succinic acid linker units of compounds 1b-1f show similar coupling patterns but have overlap of one or more of the succinic acid resonances.

- 21.(a) Brink M. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:7005–7011. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zetta L, Gatti G. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:3773–3779. [Google Scholar]

- 22.An HMQC experiment establishes that Ha and Ha′ are attached to one carbon atom and that Hb and Hb′ are attached to another carbon atom.

- 23.It should also be possible to create a peptide system that dimerizes through parallel β-sheet formation by C-terminally linking two peptides with a diamine unit.

- 24.This intermolecular model system has an advantage over intramolecular model systems, in that it achieves the results of a double-mutant cycle experiment in a single equilibrium that does not involve an unfolded state.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Synthetic procedures and NMR spectroscopic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.