Abstract

Research was undertaken to compare Problem-Solving Treatment for Primary Care (PST-PC) to usual care (UC) for minor depression and examine whether treatment effectiveness was moderated by coping style. PST-PC is a six-session, manual-based, psychosocial skills intervention. A randomized controlled trial was conducted in two academic, primary care clinics. A total of 141 subjects were eligible and randomized, and 107 completed treatment (57 PST-PC, 50 UC) and a 35-week follow-up. Analysis using linear mixed modeling revealed significant effects of treatment and coping such that those in PST-PC improved at a faster rate, and those initially high in avoidant coping were significantly more likely to have sustained benefit from PST-PC.

Keywords: depression, psychotherapy, counseling, primary care, coping

INTRODUCTION

Minor depression, defined as relatively sustained depressed mood without the full syndrome that characterizes major depressive disorder, is one of the most common types of depressive disorders (Beekman et al., 1995; Blazer, Hughes, & George, 1987). This is particularly true in primary care with rates of minor depression as much as four times greater than major depression (Barrett, Barrett, Oxman, & Gerber, 1988; Broadhead, Blazer, George, & Tse, 1990; Jaffe, Froom, & Galambos, 1994; Williams, Kerber, Mulrow, Medina, & Aguilar, 1995). If persons are to be treated for minor depression, it is most likely to occur in the primary care setting (Barrett et al., 1988; Garrard et al., 1998; Regier et al., 1993).

Despite the high prevalence and associated functional impairment, there is limited evidence that antidepressants are of clinically significant benefit to persons with minor depression (Goldberg, Privett, Ustun, Simon, & Linden, 1998; Guy, Ban, & Schaffer, 1983; Linden et al., 1999; Paykel, Freeling, & Hollyman, 1988) (but see (Judd et al., 2004). Similarly, for people with minor depression, there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of manual driven, structured psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (Cuijpers, van Straten, & Warmerdam, 2007; Oxman & Sengupta, 2002) or the most widely used psychosocial treatment in primary care, nonspecific “counseling” (Orleans, George, Houpt, & Brodie, 1985; Robinson et al., 1995; Spitzer et al., 1995).

Problem Solving Treatment for Primary Care

Because minor depression is often a reaction to the multiple stresses and strains of life, coping interventions such as problem solving therapies would seem to be an ideal treatment. In recent meta-analyses, problem solving therapy, was superior to no treatment, treatment as usual, and attention placebo for treating major depressive disorder (Cuijpers, van Straten et al., 2007; Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, 2007). The problem solving treatment tested in the current study for minor depression is a brief variant of social problem solving therapy (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 1999). It is a psychosocial skills training intervention originally designed and tested in the United Kingdom as a treatment for emotional distress in primary care (Catalan, Gath, Bond, Day, & Hall, 1991). It has since been shown to be effective in treating major depression in primary care (Mynors-Wallis, 2002; Mynors-Wallis, Gath, Lloyd-Thomas, & Tomlinson, 1995). During the past ten years the intervention has been adapted and elaborated for investigation in the United States (Barrett et al., 2001; Unutzer et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2000). It has been coined Problem Solving Treatment for Primary Care or PST-PC. PST-PC consists of six sessions lasting 30 minutes each. PST-PC can be delivered by non-mental health professionals, such as nurses and social workers. In PST-PC the entire problem solving skill set is introduced in the first session and the skills are reinforced at each of the subsequent sessions.

Coping Styles and Depression

Given that PST-PC focuses on coping skills, it is reasonable to expect that its effectiveness may be moderated by individual differences in coping styles. Researchers have long noted an association between individual differences in coping styles and depressive symptomatology (e.g., (Billings & Moos, 1984; Folkman & Lazarus, 1986). A recent comprehensive review of the literature identifies the three most frequent categories of coping style as problem-solving, avoidance, and seeking social support (Skinner, Edge, Alman, & Sherwood, 2003). A meta-analysis of studies on the association of coping styles with physical and psychological health found that the largest effect size involved the negative association between avoidance and psychological health (Penley, Tomaka, & Wiebe, 2002). With respect to depression, an avoidant coping style has regularly been shown to be associated with increased depression among adolescents (Gomez & McLaren, 2006), young adults (e.g., (Penland, Masten, Zelhart, Fournet, & Callahan, 2000), new mothers (e.g., (Terry, Mayocchi, & Hynes, 1996), late middle-aged adults (e.g., (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Brennan, & Schutte, 2005) and the elderly (e.g., (Mausbach et al., 2006). In addition, avoidant coping appears to interfere with spontaneous improvement in minor depression (Hegel, Oxman, Hull, Swain, & Swick, 2006).

Given that PST-PC is focused on decreasing behavioral avoidance of problems (Moorey, Holting, Hughes, Knynenberg, & Michael, 2001) by problem-focused engagement, the differential effectiveness of treatment may be qualified by individual differences in coping style. Specifically, PST-PC may train individuals to compensate for characteristics that they lack. In such a compensatory model, PST-PC should have the greatest effectiveness among individuals low in problem-focused coping and use of social support and/or high in avoidance. The purpose of the present research was to test the therapeutic effect of PST-PC compared to usual care for persistent minor depression in primary care and examine the extent to which its effectiveness is moderated by individual differences in coping styles.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

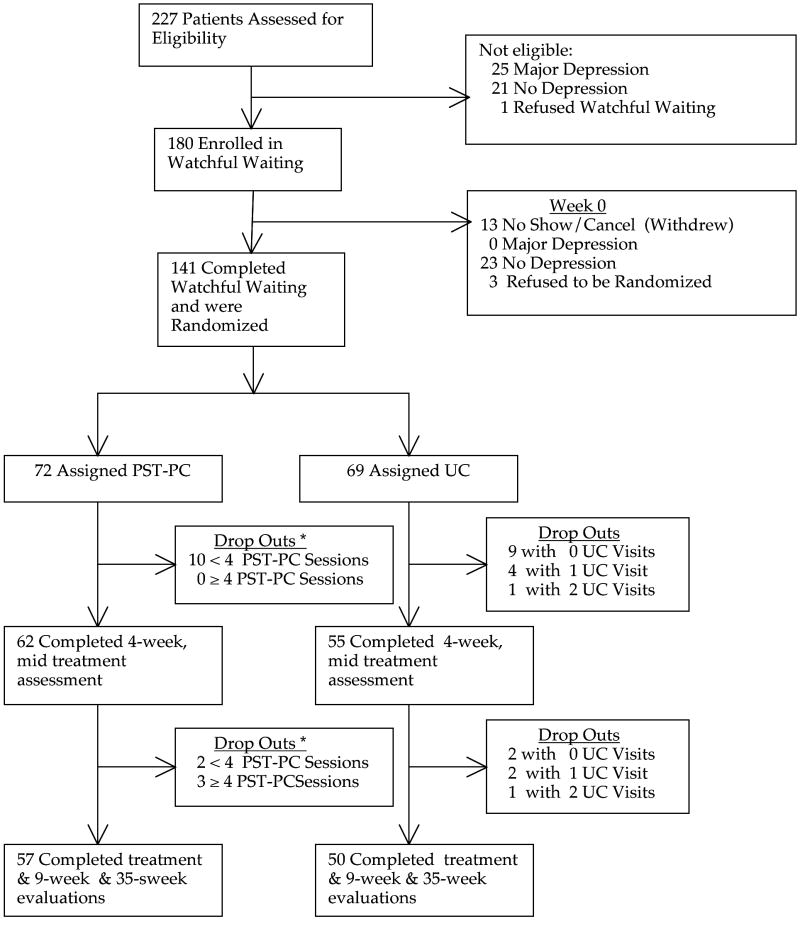

Participants came from two academic primary care clinics. The first was a general internal medicine clinic with 20 board-certified staff internists and over 16,000 patients age 18 or older. Patients in this clinic have a mean age of 53 and are 57% female. The second was a family medicine clinic with nine board-certified family physicians and over 5,500 patients. Patients in this clinic had a mean age of 42 and are 67% female. Patients were mailed or received in the primary care clinic waiting room a depression screen, the PHQ-9 (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999), prior to an appointment with their primary care clinician (PCC). Patients could also be referred by their PCC based on the PCC’s clinical assessment of depression. For the period January 1, 2003 through May 31, 2006, 12,486 screens were administered. Of these 8,215 screens were returned (66%). Of these 2202 (27%) were positive (i.e., endorsed depressed mood or anhedonia as being present for at least some of the days in the past two weeks, (Whooley, Avins, Miranda, & Browner, 1997). Among these 2,202, 402 (18%) provided their name and phone number consenting to be contacted about the study. During this same period 110 patients were referred directly by their PCC. Of the 512 patients referred in either manner, 283 (55%) were successfully contacted and agreed to be scheduled for a study evaluation and 227 completed the evaluation, 132 (58%) of whom were from screening and 95 (42%) from PCC referral (see Figure 1). The medical school’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the study. A complete description of the study was provided to the patient, and written informed consent was obtained.

Figure 1. CONSORT flowchart.

PST-PC = problem-solving treatment for primary care; UC = usual care.

*Attending 4 or more sessions of PST-PC is considered adequate treatment (Williams et al., 2000).

At their referral intake, subjects were evaluated by a research mental health clinician using a semi-structured interview to assess eligibility, a modified PRIME-MD (Spitzer et al., 1994). Inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of minor depression consisting of 2 to 4 DSM-IV symptoms of depression, one of which was depressed mood or anhedonia; presence of symptoms for at least two weeks but less than two years; impaired daily function; score ≥ 10 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD, Hamilton, 1967); age 18 or older. Exclusion criteria were as follows: major depressive disorder within previous six months; dysthymia; current antidepressant drug use; current treatment with a psychotherapist; major psychiatric co-morbidity (psychosis, bipolar affective disorder, PTSD, substance abuse within past six months; acute suicidal risk). 180 subjects met eligibility criteria and were entered into a four-week watchful waiting period.

The purpose of the watchful waiting phase was to identify patients with persistent minor depression. After four weeks, subjects were re-evaluated to see if they still met eligibility criteria, and if so were randomized. Randomization was stratified by gender and age group (18 to 59 and 60 and older). A randomization list for each strata was independently prepared by a statistician in blocks of four, consecutively assigned by a research assistant who kept the assessors blind to assignment. Subjects were re-evaluated for depressive symptoms at four, nine, and 35 weeks after randomization.

Interventions

PST-PC

PST-PC is a six-session intervention, which took place over a nine week period. The first PST-PC treatment session was one hour in length and included an assessment of the patient’s problems, an explanation of the rationale of treatment, establishing a positive problem orientation, and a complete problem solving treatment session. This initial problem solving treatment session consisted of taking the patient through six problem solving steps. First, a problem was clarified, evaluated for barriers to its resolution, and an objective problem definition was developed. Second, an achievable goal was developed that could be accomplished prior to the next treatment session. Importance was placed on the goal addressing the barriers identified in the previous step. Third, multiple solution alternatives were identified via brainstorming. Fourth, each solution was evaluated for its unique advantages (pros) as well as obstacles to its implementation (cons) and one or more solutions were chosen for implementation. Fifth, a specific plan of action was designed for implementing the solution prior to the subsequent visit. The second through sixth sessions were approximately 30 minutes in length. These sessions were entirely dedicated to implementing the PST-PC strategy for at least one problem area. Each of these sessions began by completing the sixth step of PST-PC that was to evaluate the implementation of the solution from the previous session. In keeping with the prototype for PST-PC developed in the UK, time was also spent discussing and planning regular pleasant activities (e.g., leisure, social, and recreational activities) to be completed between sessions.

Two masters level counselors were trained to provide PST-PC in a program consisting of a one-day workshop with demonstrations and role play, a comprehensive treatment manual (Hegel & Arean, 2003), and five supervised training cases consisting of six sessions each. Each therapist was determined to have met basic competency criteria as defined by at least a “satisfactory” performance for each session of their last two training cases.

Usual Care

Patients randomized to UC had a visit scheduled with their PCC within four weeks. Patients were urged to discuss treatment options with their PCC. While the provision of a diagnosis to both patient and PCC and the scheduling of a follow-up appointment were a deviation from UC (necessitated by ethical and practical considerations), the intervention in other respects was to approximate routine physician practice in non-research circumstances. PCCs had the option of suggesting additional watchful waiting, prescribing antidepressants, and/or providing brief supportive counseling or external referral to specialty mental health.

Measures

Assessments took place at five time points: recruitment (“- 4 weeks”), end of watchful waiting / randomization (“week 0”), mid-treatment (“week 4”), end of treatment (“week 9”), and six-month follow-up (“week 35”). The following measures were used.

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)

The 17-item HAM-D (Hamilton, 1967) was used as an eligibility criterion for entry into watchful waiting and subsequently into the treatment study (HAM-D ≥ 10) (Barrett et al., 2001; Williams et al., 2000). The items are rated during a clinical interview with a score range from 0 to 53. The HAM-D was administered at weeks -4, 0, 4, 9, 35.

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

The 10-item, observer-rated MADRS was used as the principle measure of improvement for these analyses. MADRS items are rated on a 0-to-6 severity scale, resulting in a total score range of 0 to 60. The MADRS is sensitive to treatment change (Davidson, Turnbull, & Strickland, 1986; Montgomery & Asberg, 1979). The MADRS focuses primarily on psychic symptoms of depression. In medical patients this helps in distinguishing treatment effects on depression from comorbid medical symptoms (McDowell, 1996). Also, the MADRS was not subject to being potentially confounded and limited in range by use as an eligibility criterion for entry into the RCT, as was the HAM-D. The MADRS was administered at weeks -4, 0, 4, 9, 35. A standardized coefficient alpha of .75 to .89 was observed over the course of the study.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist 20-item Depression Scale (HSCL-d-20)

The HSCL-d-20 was a secondary, self-report measure of depressive symptoms. This 20-item depression scale (Katon et al., 1995) is derived from the 90-item HSCL (Lipman, Covi, & Shapiro, 1979). Items are rated on a 5-point scale (0 to 4) according to how much the symptom has been experienced during the past week. Scale scores are determined by dividing the sum of the items by the total number of items, yielding a range of 0-4. The HSCL-d-20 was administered at weeks -4, 0, 4, 9, 35. A standardized coefficient alpha of .86 to .92 was observed over the course of the study.

Brief COPE

The Brief COPE (Carver, 1997), a shortened version of the original COPE (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989), has 28 self-report items that combine to form 14 subscales of coping reactions. Based on previous confirmatory factor analyses of the original COPE (Tedlie, 1993), we were particularly interested in three subcomponents: problem focused coping (e.g., “I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better”), using social support, and avoidant coping (e.g., “I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope”). A principal components analysis applied to earlier data provided additional support for this factor structure (Hegel et al., 2006). Subscales were created for each of the theorized coping factors (Problem-focused Coping, six items, alpha = .79; Social Coping, four items, alpha = .82; Avoidant Coping, four items, alpha = .68). Items are rated on a 4-point scale (0-3) according to how much they pertain to the person. The Brief COPE was administered at weeks -4 and 35.

Medical Outcomes Short Form-36 (SF-36)

The SF-36 is a multidimensional measure of function developed by the RAND Corporation from the Health Insurance Experiment (Wells et al., 1989). We selected the role emotional scale as the most specific descriptor of functional impairment from depression and one of the two standardized component summary measures (physical component score, PCS) of the SF-36 to measure functional impairment from medical conditions to control for this influence on depression outcomes. We did not use the mental health component summary measure because it includes depressive symptoms and, thus, is not an independent measure of function. The SF-36 was administered at weeks -4, 0, 9, and 35.

Problem Solving Treatment for Primary Care Adherence and Competence Scale (PST-PAC)

The PST-PAC was used as the measure of therapist fidelity to the PST-PC protocol. The PST-PAC was completed by the PST-PC trainer/supervisor based on audiotape review of treatment sessions. The PST-PAC is comprised of seven items scored on a 0 to 5 scale (0=very poor, 5=very good). Six items assess fidelity to technical skills, completing the six specific problem solving stages, with an internal consistency alpha from .83 to .89 and an average inter-rater agreement per item (defined as agreement on the rating plus or minus 1 point) of 86%. The seventh item is a global rating of the overall performance of the therapist taking into account patient and problem complexity (Hegel, Dietrich, Seville, & Jordan, 2004).

Care as Usual Treatment (CUT)

The CUT is a 47-item self-report we constructed to collect information on the use of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions for depression during the treatment trial. The CUT was administered at weeks 0, 9, and 35. Because very few patients in PST-PC used outside treatment, the primary analytic purpose of the CUT was to assess the use of antidepressants or outside psychotherapy in usual care over the treatment trial. One dichotomous variable was the use or non-use of such therapies. A second variable was a four-point Likert scale, by blind rating, for the adequacy of the treatment based on additional questions in the CUT.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted bivariate analyses to compare demographic and clinical characteristics of PST-PC and UC patients at baseline and primary hypotheses regarding treatment and coping styles were tested by intention to treat analysis using a linear mixed model with five time periods. Because we assumed non-linearity over time, time was treated as a repeated factor. Treatment (PST-PC versus UC) was treated as a time-invariant factor and the three coping styles (Avoidant Coping, Problem-focused Coping, and Social Coping) were treated as time-invariant, continuous covariates. We assessed fixed effects for these variables and their interactions in a fully factorial design using SPSS Mixed with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. A variety of initial models that varied solely in their specification of the error variance-covariance matrix were compared using Schwarz’s Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) as a parsimonious index of model fit in order to identify the most appropriate error structure to assume when testing our hypotheses. Following tests of our primary hypotheses regarding the effects of Time, Treatment, and Coping Styles, analyses were conducted that controlled for background variables (gender, age group, education, recruitment site, and marital status) as well as use of treatment (CUT) and physical functioning (SF-36 PCS). For recruitment purposes, a power analysis was based on an effect size from earlier work (Williams et al., 2000). We estimated that a sample size of 136 and a clinically significant difference (e.g. a 25% difference in depression remission) would result in a power of 80% with alpha set at 0.05. Finally, a series of analyses were conducted to assess the clinical significance of observed change.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 167 subjects completed watchful waiting. Of these, 141 were still eligible and randomized, 72 to PST-PC and 69 to UC (see Figure 1). Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of both groups appear in Table 1. The randomized group included a wide variation in duration of minor depression with a mean of almost one year, (50.84 ± 37.12 weeks) and a relatively high level of impairment (SF-36 role emotional = 41.37 ± 39.01). Consistent with the sociodemographics of the population served by the clinics, 54% had a college education, 68% had an income > $40,000, and there was little impairment from medical comorbidity (mean SF-36 PCS of 74.18 ± 23.70). There was a significant difference between the two treatment groups only in employment, with 10% more persons in the UC group employed and a trend for more comorbid panic disorder in the UC group.

Table 1. Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total (n=141) Number (%) or Mean (SD) | PST-PC (n=72) Number (%) or Mean (SD) | UC (n=69) Number (%) or Mean (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.2 (16.0) | 54.9 (16.5) | 55.5 (15.5) | > .25 |

| Female | 82 (58.2%) | 42 (58.3%) | 40 (58.0%) | > .25 |

| Married | 90 (63.8%) | 47 (65.3%) | 43 (62.3%) | > .25 |

| Race, Caucasian | 136 (96.5%) | 70 (97.2%) | 66 (95.7%) | > .25 |

| Education < college | 65 (46.1%) | 32 (44.4%) | 33 (47.8%) | > .25 |

| Employed at least part-time | 90 (63.8%) | 42 (58.3%) | 48 (69.6%) | 0.05 |

| Household Income < $40,000 | 45 (31.9%) | 23 (32.0%) | 22 (32.0%) | > .25 |

| Depression Severity

|

||||

| MADRS | 18.66 (4.39) | 18.72 (4.53) | 18.59 (4.28) | > .25 |

| HSCL-20 | 1.42 (0.60) | 1.46 (0.62) | 1.37 (0.58) | > .25 |

| Duration of episode (weeks) | 50.84 (37.12) | 51.60 (37.09) | 50.06 (37.43) | > .25 |

| Impairment (SF-36 Role-Emotional | 41.37 (39.01) | 39.35 (39.69) | 43.48 (38.48) | > .25 |

| Prior Episodes of Depressive Disorder

|

||||

| Number of previous episodes | 4.47 (4.99) | 4.94 (4.98) | 3.95 (5.01) | > .25 |

| More severe previous episode | 60 (66.7%) | 47 (65.2%) | 43 (62.3%) | > .25 |

| Treatment for most severe prior episode | 66 (73.3%) | 35 (74.5%) | 31 (72.1%) | > .25 |

| Comorbidity

|

||||

| Panic Disorder | 6 (4.3%) | 1 (1.4%) | 5 (7.2%) | 0.09 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 25 (17.7%) | 12 (16.7%) | 13 (18.8%) | > .25 |

| Physical Function (SF-36 physical component) | 74.18 (23.7) | 75.14 (23.56) | 73.19 (24.07) | > .25 |

| Coping

|

||||

| Problem Focused Coping | 8.40 (3.55) | 8.56 (3.11) | 8.24 (3.99) | > .25 |

| Avoidant Coping | 1.98 (2.08) | 2.21 (2.27) | 1.74 (1.85) | > .25 |

| Social Coping | 3.97 (2.64) | 4.06 (2.51) | 3.88 (2.78) | > .15 |

Therapy Characteristics

Less than 30% of UC subjects received or accepted a prescription for antidepressants. No patients in PST-PC reported taking a prescription drug for antidepressants. Similarly, only 4 (5.8%) of subjects in UC and three (4.2%) of PST-PC subjects reported having one or more appointments with an outside mental health professional. Fifty-six of 69 (81.2%) UC subjects had at least one depression-related visit with their PCC.

Therapists were not unique to site. They alternated assignment of subjects randomized to PST-PC unless scheduling prevented a patient being seen initially within two weeks. Because of scheduling availability of the therapists and patients, therapist 1 had 10 subjects at the family medicine site and therapist 2 only had 3 subjects at the family medicine site. The therapists had equal numbers of patients at the general internal medicine site.

The independent evaluators were asked to guess randomization assignment. They correctly guessed for 48% of PST-PC assigned subjects and for 62% of UC assigned subjects (χ2 =1.56, p=0.21, Kappa = 0.10). There was no difference in correct guessing between the two evaluators.

PST-PC sessions were audio recorded and a random selection of one-third of sessions (n=59) were analyzed for adherence. The therapists achieved an adequate mean (SD) score or better (≥ 3) on the technical skills of treatment: defining the problem 4.31 (±1.25), establishing realistic goals 4.39 (±1.31), generating solutions 4.20 (±1.34), choosing solutions 3.69 (±1.43), implementing solutions 4.25 (±1.55), and evaluating outcome 4.25 (±0.98). On the global measure of treatment quality a mean rating of 3.92 (±0.97) (good to very good) was achieved. Therapist 1 was rated significantly higher than therapist 2 on 5 of the 7 scales. However, There were no significant differences in MADRS or HSCL scores at any time point between therapists (p values ranging from a low of 0.237 for MADRS before randomization to 0.925 at week 9).

Attrition

Of the 141 participants randomized to receive either PST-PC or UC, 107 completed treatment (PST-PC = 57/72; UC = 50/69; χ2 = .86, n.s.). Completers were compared to noncompleters on all baseline and clinical characteristics that appear in Table 1. Completers were younger, t(139) = -3.099, p = .002, had better physical functioning as measured by the SF-36 PCS, t(139) = 2.295, p = .023, and were less likely to be suffering from a panic disorder, χ2(1) = 12.01, p = .003, Fischer’s Exact Test.

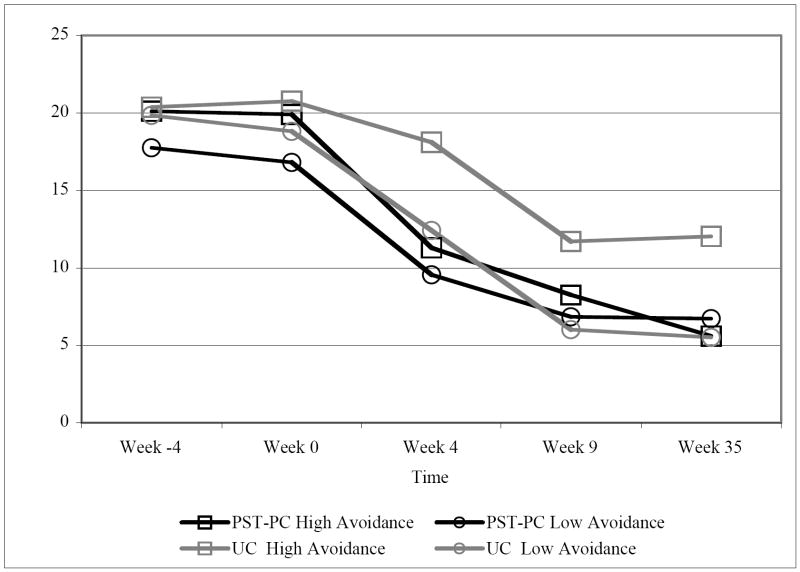

Depression

For the primary analyses, the MADRS measure of depression was treated as a continuous variable assessed at five time points, with Time treated as a repeated factor, Treatment as a fixed factor, and each coping style as continuous covariates in a fully factorial linear mixed model. This analysis revealed a main effect of Time, F(4,166.279) = 101.367, p < .001, such that participants showed decreases in depression over the course of the study. In addition, there was a significant effect of Treatment, F(1,107.597) = 8.352, p < .01, such that patients receiving PST generally had lower levels of depression than those receiving UC (although this was not the case at Week 0). The Time by Treatment interaction approached conventional levels of significance, F(4,166.279) = 2.33, p = .058, such that individuals in the PST-PC group appeared to improve at a faster rate over the course of treatment and follow-up compared to those in UC. With respect to coping styles, there was a significant main effect of Avoidant Coping, F(1,105.464) = 9.163, p = .003, and a Time by Treatment by Avoidant Coping interaction, F(4,157.945) = 3.626, p = .007. The latter interaction is depicted in Figure 2.1 It can be seen in this figure that those high in Avoidance assigned to UC improved less than (a) those high in Avoidance assigned to PST and (b) those low in Avoidant Coping in either treatment group.

Figure 2. Depression as a function of Time, Treatment, and Avoidance Coping as assessed by Observer-Rating (MADRS).

Note. Avoidance coping is treated as a continuous measure. As a consequence, the plotted values do not represent means. Rather they represent constructed values for individuals one standard deviation above and below the mean in Avoidance. 1

In addition to these effects, there was a significant main effect of Problem-focused Coping, F(1,123.857) = 4.850, p = .029, and a Problem-focused Coping by Time interaction, F(4,164.840) = 2.580, p = .039. Although those high in Problem-focused Coping began treatment at a slightly lower level of depression, they improved at a slower rate over the course of the study. In addition, there was a three-way interaction of Problem-focused Coping, Social Coping, and Treatment, F(1,98.676) = 7.801, p = .006. High Problem-focused, high Social Coping individuals randomly assigned to Usual Care, and low Problem-focused, low Social Coping individuals randomly assigned to PST, started at Week 0 with lower levels of depression. Because this interaction involved Treatment but existed prior to treatment initiation (Week 0), and because it was non-significant at Weeks 4, 9, and 35 when Week 0 MADRS levels were covaried, it was attributed to the vagaries of random assignment.

These analyses were also conducted using the following covariates entered as a block: Marital status, Education level, Age, Gender, Physical functioning, Recruitment site, Use of other treatments, and Use of treatments by Time. This had the effect of rendering the interaction of Treatment and Time significant at conventional levels, F(4,164.369) = 3.354, p = .011. All seven of the other effects remained statistically significant. Of the demographic covariates in the final model, only Education, F(1,135.461) = 5.073, p = .026, achieved significance such that those with higher education were less depressed. A final covariance analysis conducted within the PST-PC treatment condition revealed that when Therapist was included as a covariate it was not statistically significant and did not alter the level of significance of any of the remaining effects.

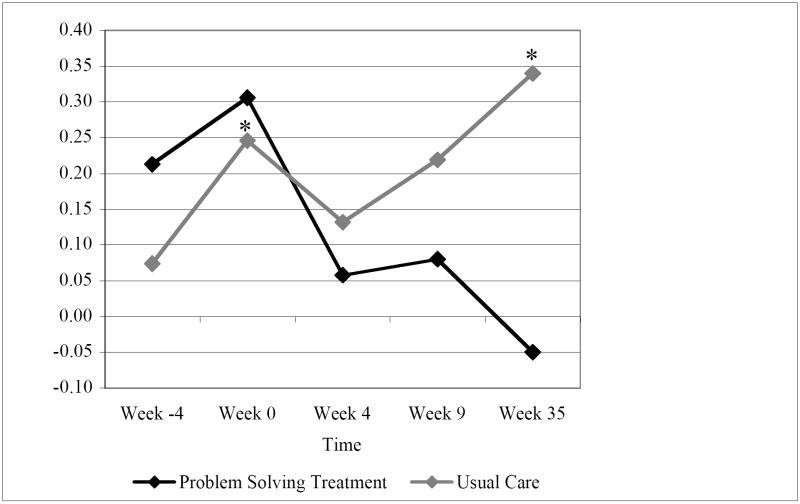

A follow-up set of analyses were conducted in order to provide support for the interpretation of the Time by Treatment by Avoidant Coping interaction in terms of the ineffectiveness of UC among those high in Avoidant Coping. Given that both depression and Avoidant Coping were assessed as continuous variables, this interaction can be viewed in terms of variation in their intercorrelation as a function of the discrete variables of Time and Treatment. This variation is depicted in Figure 3. Avoidant Coping (as measured four weeks prior to treatment onset) becomes more strongly associated with depression over the watchful waiting period (Week -4 to Week 0). This association then becomes weaker over the course of treatment (Week 0 to Week 9), particularly among those in PST-PC. Most strikingly, Avoidant Coping (again, as measured four weeks prior to treatment onset) is once again related to depression at the 35 week follow-up among those who had been assigned to UC, r(N=50) = .34, p = .016, but is unrelated to depression among those who had PST-PC, r(N=58) = -.05, p > .50. The size of the difference between the latter two correlations is statistically significant, z = 2.03, p = .042. This pattern supports an interpretation of the Time by Treatment by Avoidant Coping interaction in terms of the effectiveness of PST-PC relative to UC to break the association of dispositional Avoidant Coping and depression. Similar effects were not observed for Problem-Focused or Social Coping, whose correlations with depression did not achieve conventional levels of significance at any time-point.

Figure 3. Correlation of Avoidant Coping as measured at Week Minus 4 with Depression as a function of Time and Treatment.

*p < .05

As a secondary analysis, the HSCL-d-20 measure of depression was also treated as a continuous variable assessed at five time points, with Time treated as a repeated factor, Treatment as a fixed factor, and each coping style as continuous covariates in a fully factorial linear mixed model. These self-report results essentially replicated the observerrated MADRS results. There were main effects of Time, F(4,187.246) = 50.741, p < .001, Treatment, F(1,98.730) = 7.137, p < . 01, and Avoidant Coping, F(1,97.291) = 25.662, p < .001, although the main effect of Problem-focused Coping only approached conventional levels of significance, F(1,110.129) = 3.493, p = .064. Unlike the MADRS, the predicted Time by Treatment interaction achieved conventional levels of significance, F(4,187.246) = 3.903, p = .005, such that individuals in the PST-PC group improved at a faster rate over the course of treatment and follow-up compared to those in UC. In addition, although there was a significant Treatment by Avoidant Coping interaction, F(1,97.291) = 7.458, p = .007, with individuals high in Avoidance showing less improvement in UC than in PST-PC, this interaction was not qualified by Time. At the same time, univariate analyses conducted at each time period revealed that the two-way interaction of Treatment by Avoidance was only a significant interaction at the 4 week measurement period, F(1,96) = 6.548, p = .012. Although the three way interaction of Treatment, Social Coping, and Problem-focused Coping previously attributed to random assignment differences also appeared for the HSCL-d-20, F(1,93.127) = 9.327, p = .003, pre-random assignment differences diminished over the course of the study, thus yielding a four-way interaction with Time, F(4,176.823) = 3.532, p = .008. Finally, the Problem-focused Coping by Time interaction was not significant, F(4,183.487) < 1.00, n.s.

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of treatment effects was assessed following the recommendations of Jacobson (Jacobson, Roberts, Berns, & McGlinche, 1999; Jacobson & Truax, 1991). The results of a meta-analysis of control participants from ten studies was used to define the mean and standard deviation of the MADRS in the normal population (Zimmerman, Chelminski, & Posternak, 2004). Given that our initial sample distribution overlapped the normal comparison group, clinically significant change in functioning subsequent to therapy was defined as an outcome MADRS score closer to the mean of the control group than the mean of the initial sample (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). As a consequence, the criterion for clinically significant change was a MADRS score of 11.35. Of the four groups depicted in Figure 2, only the high and low Avoidance individuals in the PST-PC group fell below this value (11.35) after 4 weeks of treatment. By the end of 9 weeks of treatment, low Avoidance individuals in the UC group also fell below this value. High Avoidance individuals in the UC group never achieved clinically significant improvement according to this criterion.

Jacobson and Truax (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) also recommend using the Reliable Change Index to assess clinically significant change. Within the present sample, a reduction on the MADRS of 10.78 units would constitute clinically significant change according to this index. Relative to initial baselines, high Avoidance individuals in the UC group never achieve this criterion, whereas individuals in the other three groups achieve it after 9 weeks of treatment and maintain it through follow-up.

Although useful as a criterion to assess the clinical significance of change observed in the linear mixed model, the Reliable Change Index can also be used to define each individual as having achieved or not achieved clinically significant change relative to their own pretreatment baseline at each of the three measurement periods following treatment onset (Weeks 4, 9, and 35). These longitudinal, dichotomous data were analyzed using General Estimating Equations in a fully factorial design. Consistent with the previous analyses, this analysis yielded an interaction of Treatment and Avoidant Coping, Wald χ2(1) = 8.716, p = .003, such that participants high in avoidance were more likely to improve in PST than UC whereas this was not true for those low in avoidance. Predicted proportions for high and low avoidant individuals appear in Table 2. There was also a main effect of Time, Wald χ2 (2) = 17.808, p < .001, such that participants improved over time and a main effect of Problem-Focused Coping, Wald χ2 (1) = 6.815, p < .01, such that those low in Problem-Focused Coping were more likely to improve than those high in Problem-Focused Coping. Finally, there was an interaction of social coping and time, Wald χ2 (2) = 6.279, p = .04. Those high in Social Coping were more likely to improve early in treatment compared to those low in Social Coping.

Table 2. Predicted Proportion of Individuals with High and Low Avoidant Coping showing Clinically Significant Change.

| Week Following Treatment Initiation | PST-PC Low Avoidant Coping | UC Low Avoidant Coping | PST-PC High Avoidant Coping | UC High Avoidant Coping |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | .25 | .35 | .46 | .02 |

| Week 9 | .52 | .70 | .59 | .42 |

| Week 35 | .55 | .64 | .74 | .36 |

Note. Avoidant coping is treated as a continuous measure. The table values represent recreated proportions for individuals one standard deviation above and below the mean in Avoidance.1

Completer Analyses

All of the above intent-to-treat analyses were also conducted using repeated measures ANOVA. Because of its treatment of missing data, such an approach limits participants to those with complete data and hence all of those who completed treatment. These analyses replicated all of the essential findings of the intent-to-treat linear mixed model approach and provided stronger support for two previously observed near significant patterns. Thus, for the MADRS, the Time by Treatment interaction was significant, averaged F(3.49,61.09) = 2.522, p = .041, and for the HSCL-d-20, the Time by Treatment by Avoidance interaction was F(4,79) = 2.464, p = .052. 2

Discussion

The duration of illness and associated impairment of this patient sample supports previous assertions that minor depression should be treated (Cuijpers, Smit et al., 2007). This treatment trial suggests that a significant majority of primary care patients with persistent and relatively severe minor depression do not spontaneously improve during watchful waiting, but do improve once engaged in some form of active treatment. This treatment trial also found two significant and specific benefits for PST-PC.

First, those receiving PST-PC improved more quickly than those in UC. This effect approached significance for the uncorrected analyses of the MADRS (p = .058) and achieved significance for the covariate corrected intent-to-treat analyses and completer analyses of the MADRS and all three analyses of the HSCL-d-20. These findings are consistent with earlier work. In previous work comparing PST-PC with a placebo for minor depression in primary care, PST-PC also showed a more rapid improvement in symptoms, but not overall outcome, for adults age 60 and older (Williams et al., 2000). In a smaller study of adults age 18 to 59 with minor depression, symptom improvement with PST-PC was slower than placebo or antidepressant during the first two weeks of treatment, but faster during the next nine weeks of treatment (Barrett et al., 2001). At the end of treatment, overall symptom reduction was not significantly different. In these two earlier studies, patients in the medication or placebo interventions had more treatment visits than in the present study, yet PST-PC still showed faster symptom improvement over the course of the treatment trial. Together, these results suggest that there is something about PST-PC that improves symptoms at a faster rate and that it is not just due to the number of treatment contacts.

Second, patients relying on an avoidant coping style showed greater improvement with PST-PC than Usual Care. These differences persisted for at least six months following treatment. Similar results were observed when patients were categorized on clinically significant change in depression. These results support the hypothesized compensatory model for PST-PC. As in previous research, avoidant coping in general was more strongly related to depression than other coping styles. Taken together, these findings support the notion that PST-PC for minor depression may counteract a dispositional tendency to avoid dealing with problems, supporting the argument for matching treatment with individual characteristics (Dussseldorp, Spinhoven, Bakker, van Dyck, & van Balkom, 2007; Karno & Longabaugh, 2007; Thieme, Turk, & Flor, 2007).

A meta-analysis of PST studies found a high level of heterogeneity for unclear reasons (Cuijpers, van Straten et al., 2007). In earlier multisite trials (Barrett et al., 2001; JW Williams et al., 2000) there were indications that there may have been site differences, either in patients or therapists. These studies did not assess and control for coping styles and therefore were not designed to detect their influence. The present trial was able to address the issue of patient differences and suggests that these differences are important.

Limitations

To some extent the results of this study are limited in their generalizability given the type of patients who chose to participate. Knowing this was a study of counseling, the sample was probably self-selected for desiring non-pharmacologic treatment. Also, the sample was primarily Caucasian, with higher income and education, potentially further limiting generalizability. A large number of patients with possible minor depression did not agree to further evaluation or participation. However, we suppose that those who did participate probably were motivated by more persistent and impairing minor depression and comorbidity and thus are the ones most likely in need of some form of active treatment.

In addition, it is possible that the differential effectiveness of treatment was to some degree a function of the imbalance in the number of PST-PC vs. UC treatment contacts. However, earlier work controlling for the number of sessions resulted in similar findings (Williams et al., 2000). At the same time, it is hard to conceptualize how variation in the number of contacts would systematically affect only those with an avoidant coping style. Finally, it was observed that at alpha=.68, the reliability of the Avoidant Coping scale fell just short of the traditional .70 definition of an acceptable level of reliability. It should be kept in mind that alpha constitutes an estimated lower bound of scale reliability and that a lower alpha increases error and diminishes effect sizes rather than increasing them.

Conclusions

We feel that there are three important findings in the present study. First, all patients improved over time. The fact that marked improvement was not observed until the watchful waiting period was completed and treatment initiated, even for participants assigned to usual care, suggests that usual care interactions are relatively good at improving minor depression (Carney, Dietrich, Eliassen, Owen, & Badger, 1999). Additional research needs to be conducted to identify factors responsible for such effects. Second, relative to Usual Care, PST-PC led to greater improvement over time, but third this effect was qualified by individual differences in avoidant coping style. Patients high in avoidance assigned to Usual Care showed the least improvement over time and this was generally true regardless of measure (MADRS or HSCL-d-20), analysis (linear mixed modeling of depression as a continuous variable vs. GEE analysis of dichotomous clinically significant change), and design (intent-to-treat analyses vs. completer analyses).

On the basis of these findings it is suggested that more careful diagnosis and treatment matching may be necessary in primary care. When a primary care patient with minor depression is interested in treatment, a PCC might consider asking questions about avoidant coping. For those patients who employ avoidant coping strategies such as denial or behavioral disengagement (Carver, 1997; Carver et al., 1989), referral for a problem focused treatment may be more beneficial than standard primary care treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 MH62322 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

We thank Cynthia Hewitt for her tireless efforts in coordinating most aspects of the study, Brady Cole, MA, and Dyan Patton, MSW, for their efforts as PST-PC therapists, Janette Seville, PhD, for her assistance as an independent evaluator, Angelica Barrett for help with recruitment and retention, and Jessica Magidson for assistance with preliminary data analyses.

Footnotes

Readers not familiar with the importance of adopting this approach to testing and depicting the effects of continuous predictors are referred to MacCallum, Shaobo, Preacher & Rucker (2002) and Aiken and West (1991) respectively.

Although there are no generally accepted estimates of effect sizes in linear mixed model analyses, corresponding adjusted η2 values for the repeated measures analysis of variance conducted on the MADRS for completers were Time, η2 = .76, Treatment, η2 = .03, Time by Treatment, η2 = .09, Avoidant coping, η2 = .07, Time by Treatment by Avoidant coping, η2 = .14, Problem-focused coping, η2 = .02, Time by Problem-focused coping, η2 = .11, and Problem-focused Coping by Social Coping by Treatment, η2 = .07. Similar effect sizes were observed for the HSCL-d-20.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/ccp/

Contributor Information

Thomas E. Oxman, Departments of Psychiatry and of Community and Family Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School

Mark T. Hegel, Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Medical School

Jay G. Hull, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College

Allen J. Dietrich, Departments of Community and Family Medicine and of Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School

References

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J, Barrett J, Oxman T, Gerber P. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a primary care practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1100–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J, Williams J, Oxman T, Frank E, Katon W, Sullivan M, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: A randomized trial in patients age 18-59 years. Journal of Family Practice. 2001;50:405–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman A, Deeg D, vanTilburg T, Smit J, Hooijer C, vanTilburg W. Major and minor depression in later life: a study of prevalence and risk factors. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;36:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings A, Moos R. Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. J Personality & Social Psychology. 1984;46:877–891. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Hughes D, George L. The epidemiology of depression in an elderly community population. Gerontologist. 1987;27:281–287. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead W, Blazer D, George L, Tse C. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2524–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney PA, Dietrich AJ, Eliassen MS, Owen M, Badger LW. Recognizing and managing depression in primary care: a standardized patient study. Journal of Family Practice. 1999;48(12):965–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C, Scheier M, Weintraub J. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Personality Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan J, Gath D, Bond A, Day A, Hall L. Evaluation of a brief psychological treatment for emotional disorders in primary care. Psychological Medicine. 1991;21:1013–1018. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Smit F, Oostenbrink J, de Graaf R, Ten Have M, Beekman A. Economic costs of minor depression: A population-based study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115:229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem solving therapies for depression: A meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla T, Nezu A. Problem Solving Therapy: A Social Competence Approach to Clinical Intervention. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J, Turnbull C, Strickland R. The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale: Reliability and validity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1986;73:544–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussseldorp E, Spinhoven P, Bakker A, van Dyck R, van Balkom A. Which panic disorder patients benefit from which treatment: cognitive therapy or antidepressants? Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:154–161. doi: 10.1159/000099842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus R. Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. J Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:107–113. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J, Rolnick S, Nitz N, Luepke L, Jackson J, Fischer L, et al. Clinical detection of depression among community based elderly people with self-reported symptoms of depression. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 1998;53A:M92–M101. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.2.m92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D, Privett M, Ustun B, Simon G, Linden M. The effects of detection and treatment on the outcome of major depression in primary care: a naturalistic study in 15 cities. British Journal of General Practice. 1998;48:1840–1844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, McLaren S. The association of avoidance coping style, and perceived mother and father support with anxiety/depression among late adolescents: Applicability of resilience models. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:1165–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, Ban T, Schaffer J. Differential treatment responsiveness among mildly depressed patients. In: Clayton P, Barrett J, editors. Treatment of Depression: Old Controversies and New Approaches. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegel M, Arean PA. Problem-Solving Treatment for Primary Care: A Treatment Manual for Depression. Lebanon, NH: Project IMPACT: Dartmouth College; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel M, Dietrich AJ, Seville JL, Jordan CB. Training Residents in Problem-solving Treatment of Depression: A Pilot Feasibility and Impact Study. Family Medicine. 2004;36(3):204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegel M, Oxman T, Hull J, Swain K, Swick H. Watchful waiting for minor depression in primary care: remission rates and predictors of improvement. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C, Moos R, Holahan C, Brennan P, Schutte K. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. J Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:658–666. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Roberts L, Berns S, McGlinche J. Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: Description, application and alternatives. J Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:300–307. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A, Froom J, Galambos N. Minor depression and functional impairment. Archives of Family Medicine. 1994;3:1081–1086. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.12.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Rapaport MH, Yonkers KA, Rush AJ, Frank E, Thase ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine for acute treatment of minor depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1864–1871. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karno M, Longabaugh R. Does matching matter? Examining matches and mismatches between patient attributes and therapy techniques in alcoholism treatment. Addiction. 2007;102:587–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon GE, Bush T, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden M, Lecrubier Y, Bellantuono C, Benkert, Kisely S, Simon G. The prescribing of psychotropic drugs by primary care physicians: an international collaborative study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;19:132–140. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman R, Covi L, Shapiro A. The Hopkins Symptom Check List (HSCL): Factors derived from the HSCL-90. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1979;1:9–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(79)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R, Shaobo Z, Preacher K, Rucker D. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psycholigcal Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff J, Thorsteinsson E, Schutte N. The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach B, Aschbacher K, Patterson T, Ancoli-Israel S, von Kanel R, Mills P, et al. Avoidant coping partially mediates the relationship between patient problem behaviors and depressive symptoms in spousal Alzheimer caregivers. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:299–306. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192492.88920.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I. Measuring Health: A guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorey S, Holting C, Hughes P, Knynenberg P, Michael A. Does problem solving ability predict therapy outcome in a clinical setting? Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29(4):485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Mynors-Wallis L. Does Problem-Solving Treatment work through resolving problems? Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1315–1319. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynors-Wallis L, Gath D, Lloyd-Thomas A, Tomlinson D. Randomised controlled trial comparing Problem-Solving Treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:441–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orleans C, George L, Houpt J, Brodie H. How primary care physicians treat psychiatric disorders: a National Survey of Family Practitioners. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:52–57. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman T, Sengupta A. Treatment of minor depression. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel E, Freeling P, Hollyman J. Are tricyclic antidepressants useful for mild depression? A placebo controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1988;21:15–18. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penland E, Masten W, Zelhart P, Fournet G, Callahan T. Possible selves, depression and coping skills in university students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29:963–969. [Google Scholar]

- Penley J, Tomaka J, Wiebe J. The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes. J Behav Med. 2002;25:551–603. doi: 10.1023/a:1020641400589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P, Bush T, VonKorff M, Katon W, Lin E, Simon G, et al. Primary care physician use of cognitive behavioral techniques with depressed patients. Journal of Family Practice. 1995;40:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E, Edge K, Alman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Hahn S, Williams J, deGruy F, III, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:1511–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Williams J, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FI, Hahn S, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;14(272):1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedlie J. Coping in context: A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between emotion and coping in two stressful situations. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1993;54(6B):3392. [Google Scholar]

- Terry D, Mayocchi L, Hynes G. Depressive symptomatology in new mothers: A stress and coping perspective. J Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:220–231. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieme K, Turk D, Flor H. Responder criteria for operant and cognitive-behavioral treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rem. 2007;57:830–836. doi: 10.1002/art.22778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Stewart A, Hays R, Burnam A, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whooley M, Avins A, Miranda J, Browner W. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Barrett J, Oxman T, Frank E, Katon W, Sullivan M, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: A randomized controlled trial in older adults. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1519–1526. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Kerber C, Mulrow C, Medina A, Aguilar C. Depressive disorders in primary care: prevalence, functional disability, and identification. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1995;10:7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02599568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Posternak M. A review of studies of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale in controls: Implications for the definition of remission in treatment studies of depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacology. 2004;19:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]