Abstract

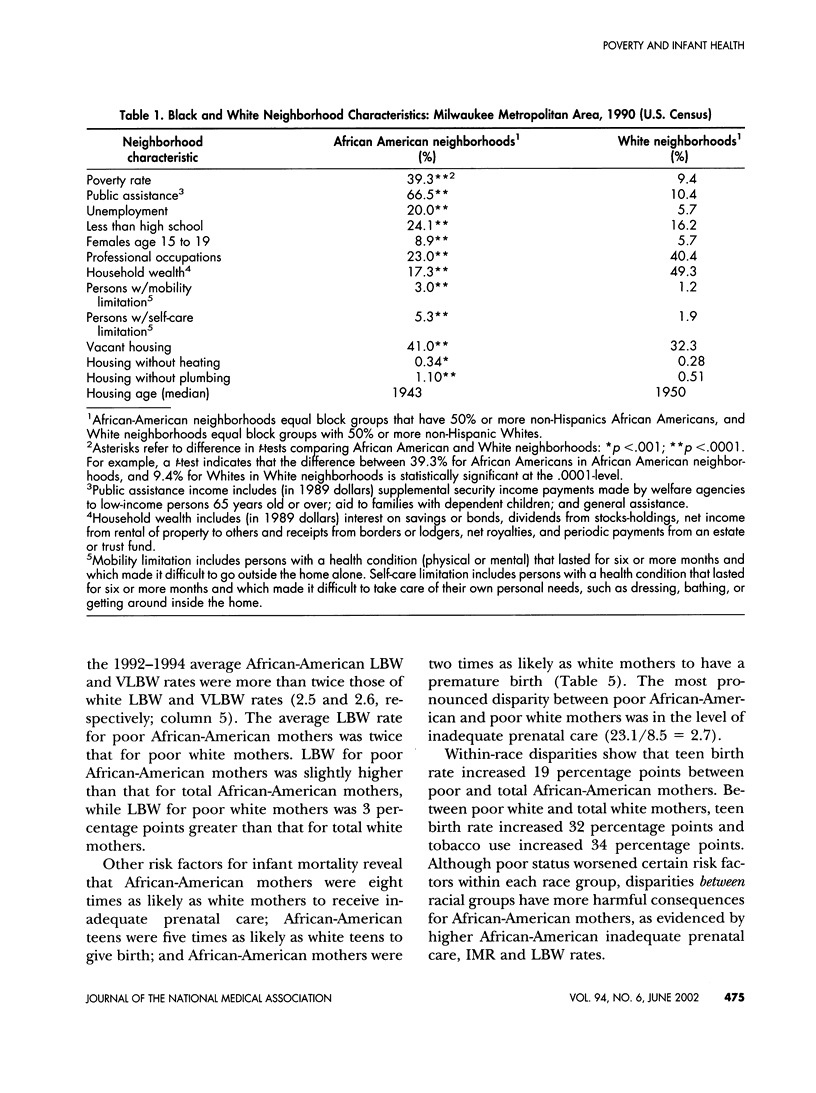

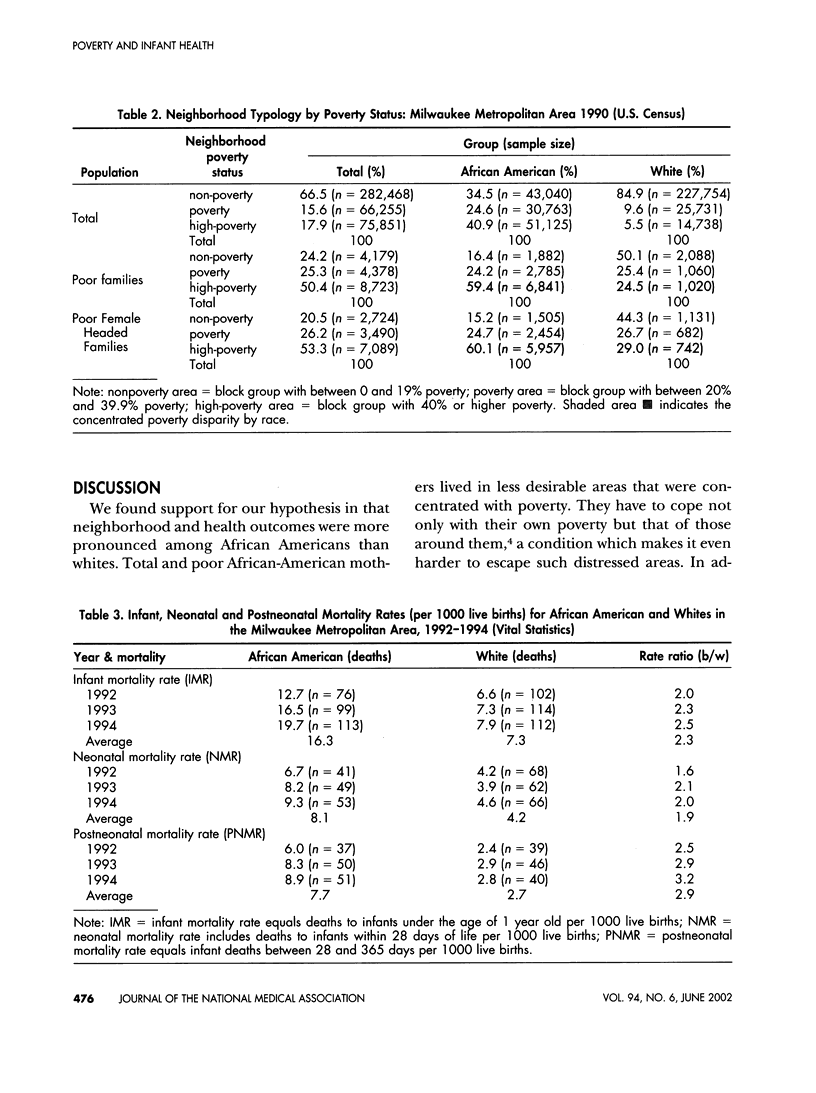

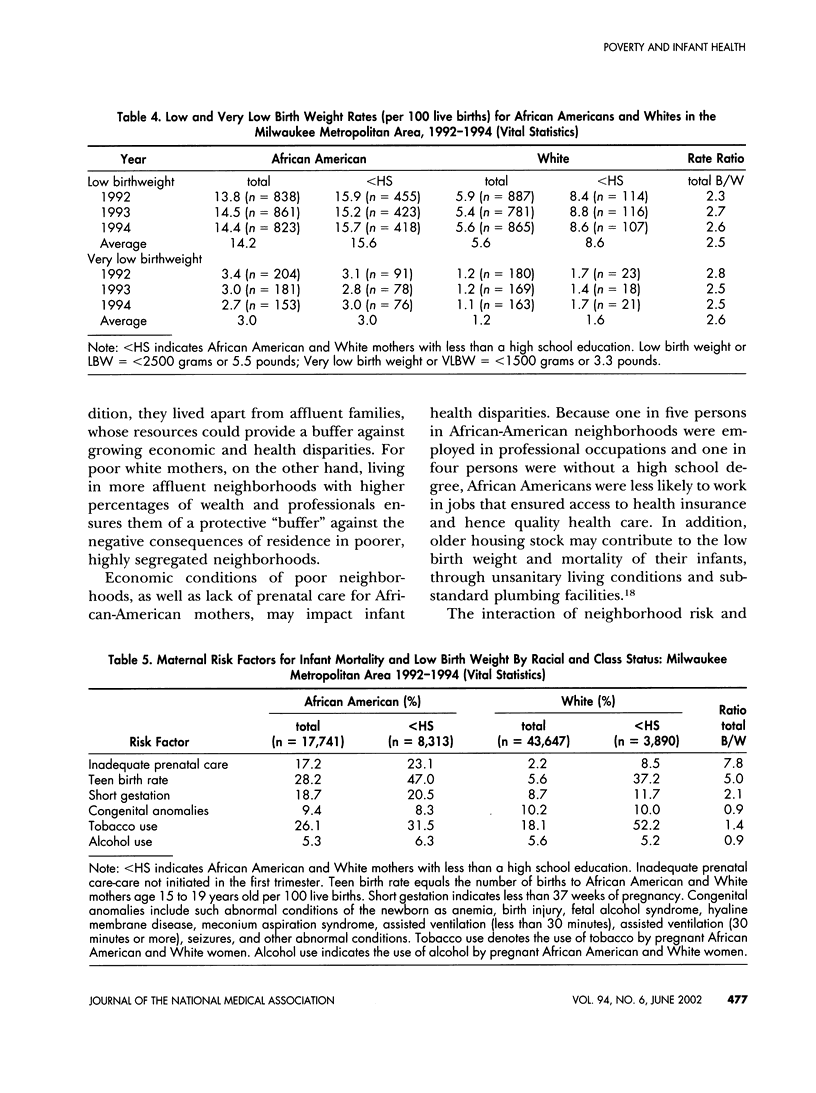

This study examined neighborhood and infant health disparities between African-American and white mothers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Census-block data were used for 1990 and Vital Statistics data were used for 1992 through 1994. African-American mothers lived in less desirable, more segregated neighborhoods than white mothers did in 1990. African-American infant and neonatal mortality rates were twice those of whites (2.3 and 2.0, respectively), while African-American postneonatal mortality rates were three times that of whites (3.0). African-American low and very low birth weight rates were more than twice those of whites (2.5 and 2.6, respectively). All African-American mothers were nearly eight times as likely as all white mothers to have inadequate prenatal care, whereas poor African-American mothers were three times as likely to have inadequate prenatal care as were poor white mothers. Public health experts and practitioners may want to consider the communities of minority patients to devise interventions suitable for addressing health disparities.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Collins J. W., Jr, David R. J. Differences in neonatal mortality by race, income, and prenatal care. Ethn Dis. 1992 Winter;2(1):18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. W., Jr, David R. J. The differential effect of traditional risk factors on infant birthweight among blacks and whites in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 1990 Jun;80(6):679–681. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.6.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L., Gallo J. J., Gonzales J. J., Vu H. T., Powe N. R., Nelson C., Ford D. E. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999 Aug 11;282(6):583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A. T. To mitigate, resist, or undo: addressing structural influences on the health of urban populations. Am J Public Health. 2000 Jun;90(6):867–872. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte T. D., Jacobs D. E. Housing and health--current issues and implications for research and programs. J Urban Health. 2000 Mar;77(1):7–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02350959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowards K. A. What is the leading cause of infant mortality? A note on the interpretation of official statistics. Am J Public Health. 1999 Nov;89(11):1752–1754. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. African-American health: the role of the social environment. J Urban Health. 1998 Jun;75(2):300–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02345099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]