Abstract

Poliovirus, a member of the enterovirus genus in the family Picornaviridae, is the causative agent of poliomyelitis. Translation of the viral genome is mediated through an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) encoded within the 5′ noncoding region (5′ NCR). IRES elements are highly structured RNA sequences that facilitate the recruitment of ribosomes for translation. Previous studies have shown that binding of a cellular protein, poly(rC) binding protein 2 (PCBP2), to a major stem-loop structure in the genomic 5′ NCR is necessary for the translation of picornaviruses containing type I IRES elements, including poliovirus, coxsackievirus, and human rhinovirus. PCBP1, an isoform that shares approximately 90% amino acid identity to PCBP2, cannot efficiently stimulate poliovirus IRES-mediated translation, most likely due to its reduced binding affinity to stem-loop IV within the poliovirus IRES. The primary differences between PCBP1 and PCBP2 are found in the so-called linker domain between the second and third K-homology (KH) domains of these proteins. We hypothesize that the linker region of PCBP2 augments binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA. To test this hypothesis, we generated six PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins. The recombinant PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins were able to interact with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA and participate in protein-protein interactions. We demonstrated that the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins with the PCBP2 linker, but not with the PCBP1 linker, were able to interact with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA, and could subsequently stimulate poliovirus IRES-mediated translation. In addition, using a monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody (directed against the PCBP2 linker domain) in mobility shift assays, we showed that the PCBP2 linker domain modulates binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA via a mechanism that is not inhibited by the antibody.

Keywords: poly(rC)-binding proteins (PCBP), cap-independent translation, poliovirus, Internal ribosome entry site (IRES), RNA secondary structure

Introduction

Poliovirus, the prototypic picornavirus, is a small positive-sense RNA virus with a genome of approximately 7500 nucleotides. The viral genome is comprised of approximately 900 noncoding nucleotides that flank a large polyprotein coding region. These 5’ and 3’ terminal sequences form extensive RNA secondary structures that are utilized to carry out several essential functions in the poliovirus replication cycle in infected cells. The RNA secondary structures act as binding sites for both host and viral proteins to mediate viral gene expression and RNA replication. One important example of the multiple RNA-protein interactions that are required during a poliovirus infection is the interaction of a cellular protein, poly(C)-binding protein 2 (PCBP2), with stem-loop IV of the 5′ noncoding region (5′ NCR) to mediate cap-independent translation initiation. The mechanism of action has not been elucidated, but it is likely that PCBP2 binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV acts to recruit ribosomes via protein-protein interactions or by stabilizing the RNA structure for internal ribosome entry (Bedard et al., 2007).

In the canonical model of cap-dependent cellular translation, the 5’ 7-methyl G cap on the messenger RNA (mRNA) acts to recruit ribosomes via a direct interaction with the eIF4F cap-binding complex (Merrick, 1990). Unlike cellular mRNAs, picornavirus genomic RNAs lack a 5’ cap structure and instead have a viral protein (termed VPg) that is covalently linked to the 5’ end of the RNA. VPg is the primer for viral RNA synthesis but does not function to recruit ribosomes for translation of the viral genome. Picornaviruses circumvent the need for a 5’ cap structure bound to an intact eIF4F complex by recruiting ribosomes to the RNA via the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) for translation initiation (Pelletier and Sonenberg, 1988; Jang et al., 1988). The exact mechanism of IRES-mediated translation initiation has not been determined; however, it has been postulated that the interaction of trans-acting host factors with cis-acting stem-loop structures acts to recruit canonical and non-canonical translation factors and/or stabilize the RNA for translation.

Several RNA-binding proteins have been identified as non-canonical translation factors that stimulate picornavirus IRES translation, including PCBP2, the La autoantigen, unr (upstream of N-ras), and polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) (Jang and Wimmer, 1990; Belsham and Sonenberg, 1996; Blyn et al., 1997; Hunt et al., 1999). PCBP2 was shown to stimulate poliovirus IRES-mediated translation via its interaction with stem-loop IV of the 5′ NCR (Blyn et al., 1995, Blyn et al., 1997). Nucleotide mutations made in poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA that abrogate PCBP2 binding subsequently inhibited viral translation (Blyn et al., 1995; Gamarnik and Andino, 2000). The requirement for PCBP2 in translation initiation is specific to picornaviruses containing a Type I IRES, which include poliovirus, coxsackievirus, and human rhinovirus (Walter et al., 1999).

PCBP2 belongs to a class of cellular proteins that bind to poly(C) stretches of both RNA and DNA (for review see Makeyev and Liebhaber, 2002). There are 4 isoforms of PCBP, PCBP1-4. Each isoform contains three K-homology (KH) domains, which are consensus RNA binding domains and fold according to a β1α1α2β2β3α3 motif (Matunis et al., 1992; Siomi et al., 1993; Dejgaard and Leffers, 1996). The poly(C) nucleotides interact with a groove that is generated between α1α2 and β2β3 (Du et al., 2004). The co-crystal structure of the PCBP2 KH1 domain with a 5’-AACCCTA-3’ DNA sequence corresponding to human telomeric DNA (htDNA) shows that PCBP2 KH1 can independently fold into the β1α1α2β2β3α3 motif (Du et al., 2004). The crystal structural also reveals that individual PCBP2 KH1 domains can dimerize on exposed surfaces opposite from the nucleotide binding sites. In addition, PCBP2 KH3 can crystallize with the same DNA sequence; however, one unique feature is that the individual KH3 domains were unable to dimerize (Fenn et al., 2007). Computer modeling of the KH2 domain of PCBP2 shows that it folds similarly to KH1 and may be capable of dimerization (Du et al., 2007). To date, the complete PCBP2 protein structure has not been determined by x-ray crystallography.

Multiple functions have been ascribed to the PCBP proteins. PCBP1 and PCBP2 have been shown to stabilize α-globin mRNAs by direct interaction with the 3′ NCR (Weiss and Liebhaber, 1995). Likewise, the interaction of PCBP1/2 with poliovirus stem-loop I of the 5′ NCR has been shown to stabilize the RNA in vitro (Murray et al., 2001). In addition to mRNA stability, the interaction of PCBPs with some mRNAs has also been shown to regulate translation. The interaction of PCBP1, PCBP2, or hnRNP K with the CU-rich motif of lipoxygenase (LOX) mRNA silences its expression (Ostareck et al., 1997). In contrast, the interaction of PCBP1, PCBP2, or hnRNP K with the IRES element of c-myc mRNA enhances its activity (Evans et al., 2003).

In addition to interacting with mRNAs, PCBPs can also participate in protein-protein interactions. In yeast-two hybrid screens, it was shown that PCBP1, PCBP2 and hnRNP K can homodimerize and heterodimerize (Kim et al., 2000; Bedard et al., 2004). In addition to variants of PCBPs, PCBP2 has been shown to interact with multiple RNA-binding proteins, including poly(A) binding protein (PABP) and two proteins involved in mRNA splicing, SRp20 and 9G8 (Funke et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1999; Bedard et al., 2007).

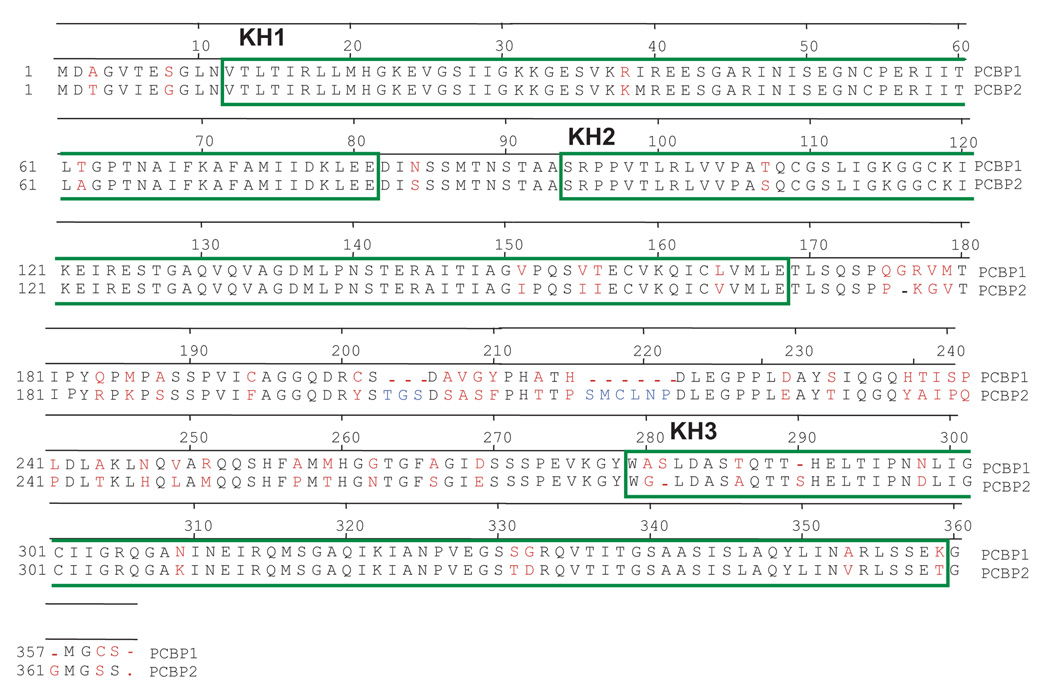

Two isoforms, PCBP1 and PCBP2, have been shown to function in the poliovirus replication cycle. Both PCBP1 and PCBP2 interact with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA (also known as cloverleaf RNA). The interaction of PCBP1/2 with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA and the viral polymerase precursor polypeptide 3CD forms the “ternary complex,” a ribonucleoprotein complex required for negative strand RNA synthesis (Andino et al., 1990; Gamarnik and Andino, 1997; Parsley et al., 1997). Previously, it was demonstrated that PCBP1 and PCBP2 have similar binding affinities for poliovirus stem-loop I RNA; however, PCBP2 has a binding affinity that is 50-fold higher than that of PCBP1 for stem-loop IV RNA (Walter et al., 2002). Also, in HeLa cytoplasmic extracts depleted of PCBPs, the addition of recombinant PCBP1 failed to rescue poliovirus IRES-mediated translation, while the addition of recombinant PCBP2 could successfully rescue viral translation (Blyn et al., 1997). Both isoforms exist in the nucleus and the cytoplasm of mammalian cells and share approximately 90% amino acid identity (Makeyev and Liebhaber, 2002). The N-termini, KH1, KH2, and KH3 of PCBP1 and PCBP2 are nearly identical; however, there are significant amino acid differences in the linker region between the KH2 and KH3 domains (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Domain compositions of PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins.

A. Amino acid sequence alignment of PCBP1 and PCBP2. The amino acid sequences of the KH domains are boxed in green. The amino acid sequences of KH1 and KH2 are nearly identical, with slight differences in KH3 and major differences in the linker region between the KH2 and KH3 domain. Amino acid differences are denoted in red and amino acids that only exist in the PCBP2 linker are denoted in blue. Dashes indicate the absence of a corresponding amino acid in one protein or the other. B. Schematic of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins. The proteins were constructed using restriction sites that were introduced at the interface of the KH2/linker (XhoI) and linker/KH3 (NheI) into a pET22 expression plasmid. KH domain and linker sequences from PCBP1 are indicated by white boxes while those from PCBP2 are indicated by black boxes.

Since the linker region has the greatest amino acid sequence diversity between PCBP1 and PCBP2, we hypothesized that this region in PCBP2 acts as an auxiliary domain to augment binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA and subsequently stimulate cap-independent translation of the genome. Here we report that PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins containing the PCBP2 linker domain, but not the PCBP1 linker domain, were able to bind stem-loop IV RNA in mobility shift assays and rescue in vitro poliovirus IRES-mediated translation in HeLa cell extracts depleted of PCBPs. Moreover, our data from RNA binding assays using recombinant PCBP2 and a monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody (specific to the PCBP2 linker domain) indicate that the PCBP2 linker modulates binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA via a mechanism that is not inhibited when complexed with the antibody.

Results

Construction of PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins

The aim of this study was to determine the basis of the binding affinity differences between PCBP1 and PCBP2 for poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA. We focused on the PCBP2 linker region as the domain that is responsible for the differential binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA due to the amino acid differences that exist between the linker domains of PCBP1 and PCBP2 (Fig. 1A). The linker regions of both of these proteins account for approximately one-third of their size, yet no known structural motifs have been described for these amino acid sequences. To test our hypothesis that the linker domain of PCBP2 acts as an auxiliary domain to augment binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA, we constructed six chimeric proteins containing different domains of PCBP1 and PCBP2 (Fig. 1B). The KH1 and KH2 domains of PCBP1 and PCBP2 are nearly identical, and these regions likely do not contribute to the observed binding differences. We constructed PCBP1-Linker/P2B and PCBP2-Linker/P1B by exchanging the linker from the respective PCBP protein. We predicted that PCBP1-Linker/P2B would represent a loss-of-function for PCBP2, and PCBP2-Linker/P1B would produce a gain-of-function for PCBP1. Constructing the PCBP1-Linker and PCBP2-Linker uncouples the linkers from the KH3 domains and also allowed us to address the relatively few amino acid differences in the KH3 domains of PCBP1 and PCBP2. To study the combined activities of the linker-KH3, we constructed PCBP1-Linker/KH3 and PCBP2-Linker/KH3.

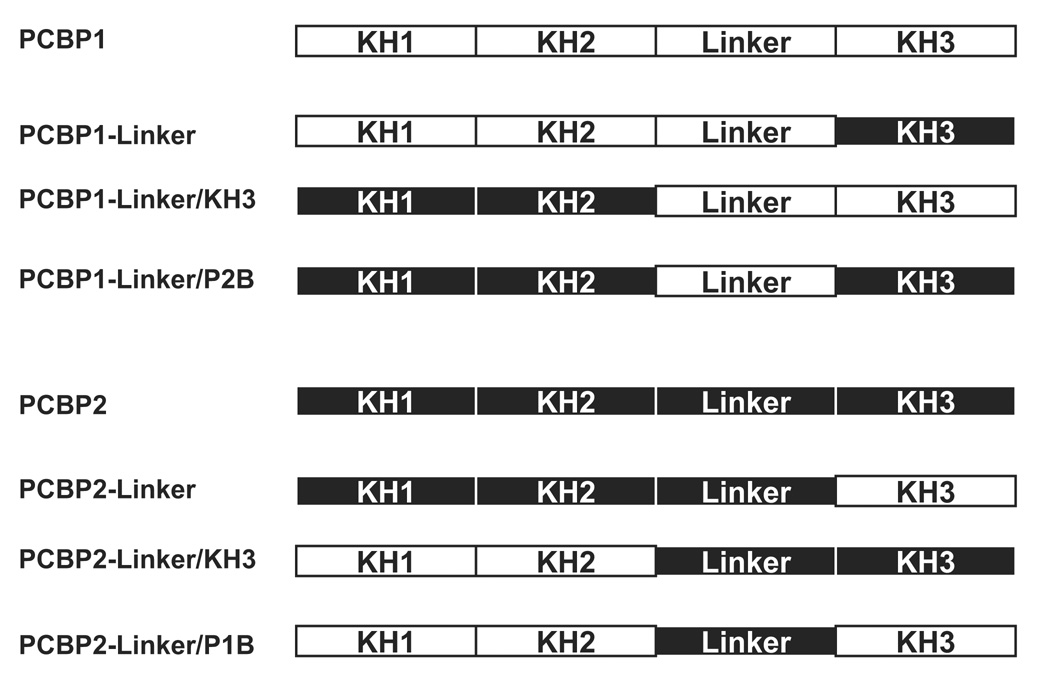

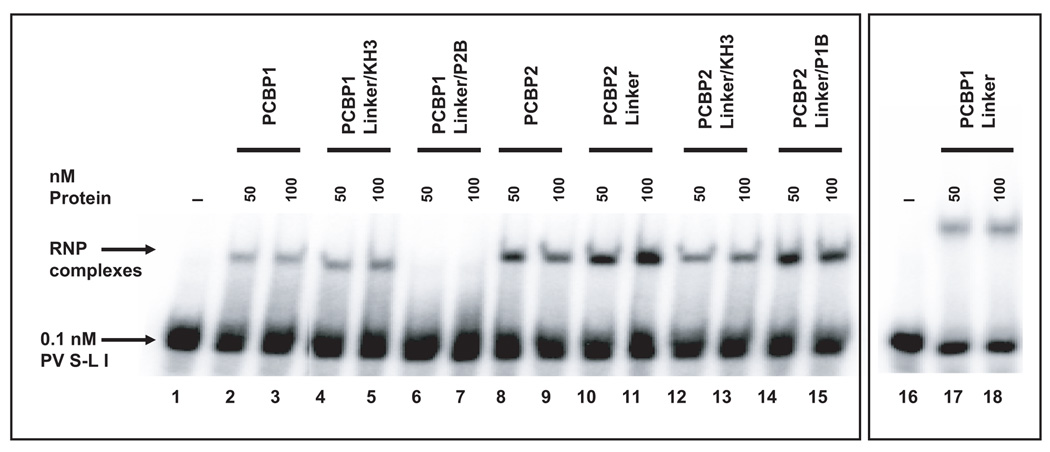

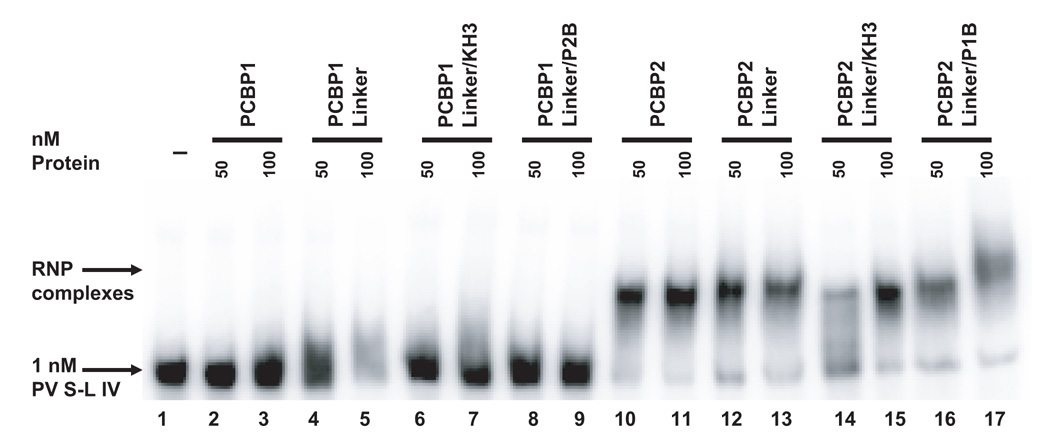

PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins can interact with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA

It was previously shown that the interaction of PCBP1 or PCBP2 with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA is an important step in viral RNA replication (Gamarnik and Andino, 1997; Parsley et al., 1997; Walter et al., 2002) [refer to the predicted stem-loop I structure in Fig. 2A]. The apparent binding affinities of PCBP1 and PCBP2 for poliovirus stem-loop I RNA are similar, with the affinity of PCBP2 for stem-loop I RNA being slightly higher (about two-fold) than PCBP1 for the same RNA (Walter et al., 2002). To determine if the purified PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins were properly folded and active in RNA binding, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA (Fig. 2B). With the exception of PCBP1-Linker/P2B, (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 7), all of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins were able to interact with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA with nearly equal relative affinities. We repeated the mobility shifts assays for poliovirus stem-loop I RNA with different preparations of PCBP1-Linker/P2B proteins multiple times and observed the same results (data not shown). When compared to the PCBP1 linker-containing chimeric proteins, the relative affinities of PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins for poliovirus stem-loop I RNA are about 2-fold greater, in agreement with previous results (Walter et al., 2002). The mobility shift assay shows that our PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins are properly folded and functionally active in binding to RNA. It should be noted that the different preparations of PCBP1-Linker/P2B have all displayed the same lack of binding to stem-loop I RNA, suggesting that this combination of PCBP domains is either functionally inactive or locally misfolded.

Figure 2. Characterization of PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins.

A. Mfold predicted RNA secondary structure of stem-loop I. The nucleotide constraints were determined by chemical and enzymatic structure probing (Skinner et al., 1989). The structure shown represents nucleotide 1 to 98 for the poliovirus type 1 genomic RNA. Poliovirus stem-loop I is predicted to form a cloverleaf-like structure. Stem-loop b and the c-rich spacer sequence, boxed, have been shown to interact with PCBP1/2 (Parsley et al., 1997; Toyoda et al., 2007). B. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA. In vitro transcribed [32P] UTP-labeled poliovirus stem-loop I RNA at a final concentration of 0.1 nM was incubated with 50 or 100 nM of purified recombinant PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric protein for 10 minutes at 30°C, and the reaction was resolved by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lanes 1 and 16 show the RNA in the absence of protein. Lanes 2–5, 8–15 and 17–18 show ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes formed by the interaction of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins with the RNA. The RNP complexes are denoted by the upper arrow. The samples in lanes 16–18 were subjected to electrophoresis for an additional hour (compared to those samples in lanes 1–15), thus accounting for the increased distance between the RNP complex and the free RNA. Lanes 6–7 show that the PCBP1-Linker/P2B chimera is unable to interact with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA.

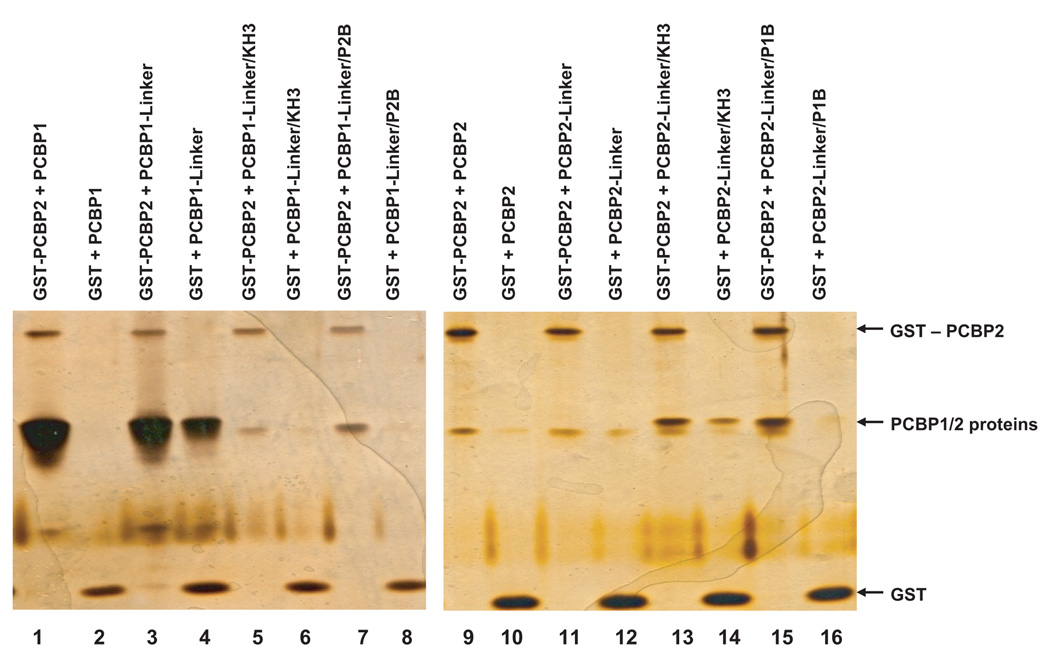

PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins can dimerize with GST-PCBP2

Using yeast two-hybrid assays, Bedard and colleagues showed that PCBP2 can homodimerize and heterodimerize with PCBP1 in vivo. The dimerization domain of PCBP2 was mapped to the KH2 domain; however, the study did not identify the dimerization domain of PCBP1 (Bedard et al., 2004). The dimerization of PCBP2 was shown to be important for poliovirus IRES-mediated translation (Bedard et al., 2004). It was also predicted that dimers of PCBP1 interact with the c-myc IRES to stimulate translation (Evans et al., 2003). To assess the protein-protein interaction capabilities of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins, we performed GST pull-down assays with GST-PCBP2 (Fig. 3). The GST pull-down results showed that all of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins are able to interact with GST-PCBP2 above the background of GST alone. In agreement with previously published results, the interaction of GST-PCBP2 with wild type PCBP1 appears to be one of higher affinity than with wild type PCBP2, suggesting that PCBPs may function as heterodimers (Fig. 3, lane 1) (Bedard et al., 2004). Interestingly, PCBP1-Linker/P2B, which is inactive in RNA binding, can dimerize with GST-PCBP2 (Fig. 3, lane 7). The GST pull-down assay shows that our PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins are properly folded and can function in protein-protein interactions with GST-PCBP2.

Figure 3. GST pull-down assays of GST-PCBP2 and PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins.

GST-PCBP2 (2 µg) and His-tagged PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins (5 µg) were subjected to pull-down assays as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1–16 show the variable interaction of GST-PCBP2 with the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins over GST alone (i.e., non-specific background interactions). Lanes 1–2 and 9–10 show the interactions of wild-type PCBP1 and PCBP2 with GST-PCBP2 and GST (control), respectively.

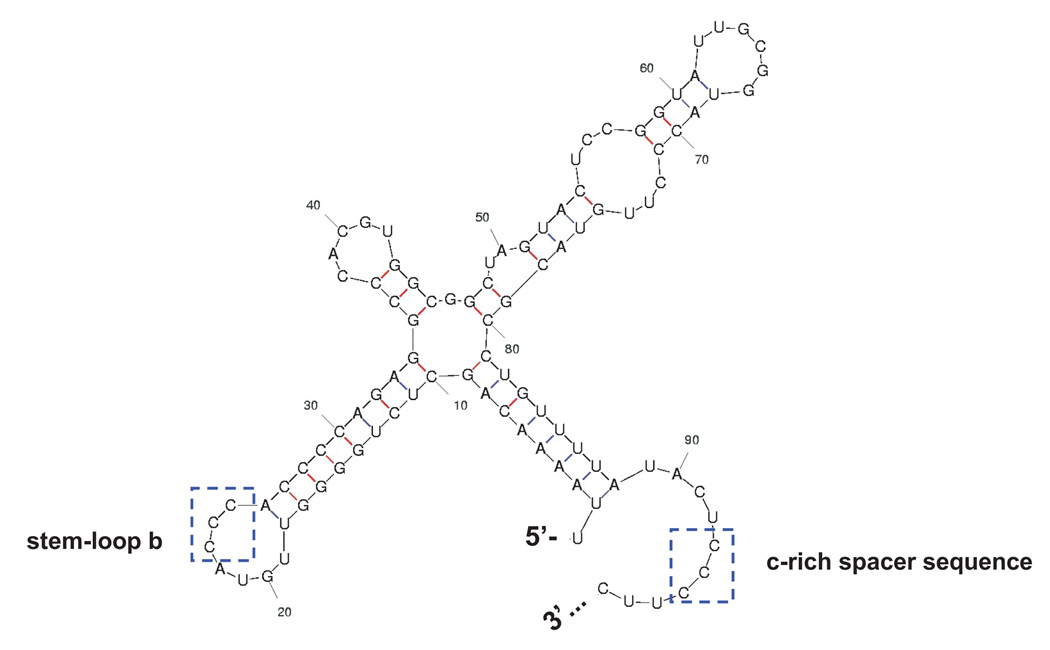

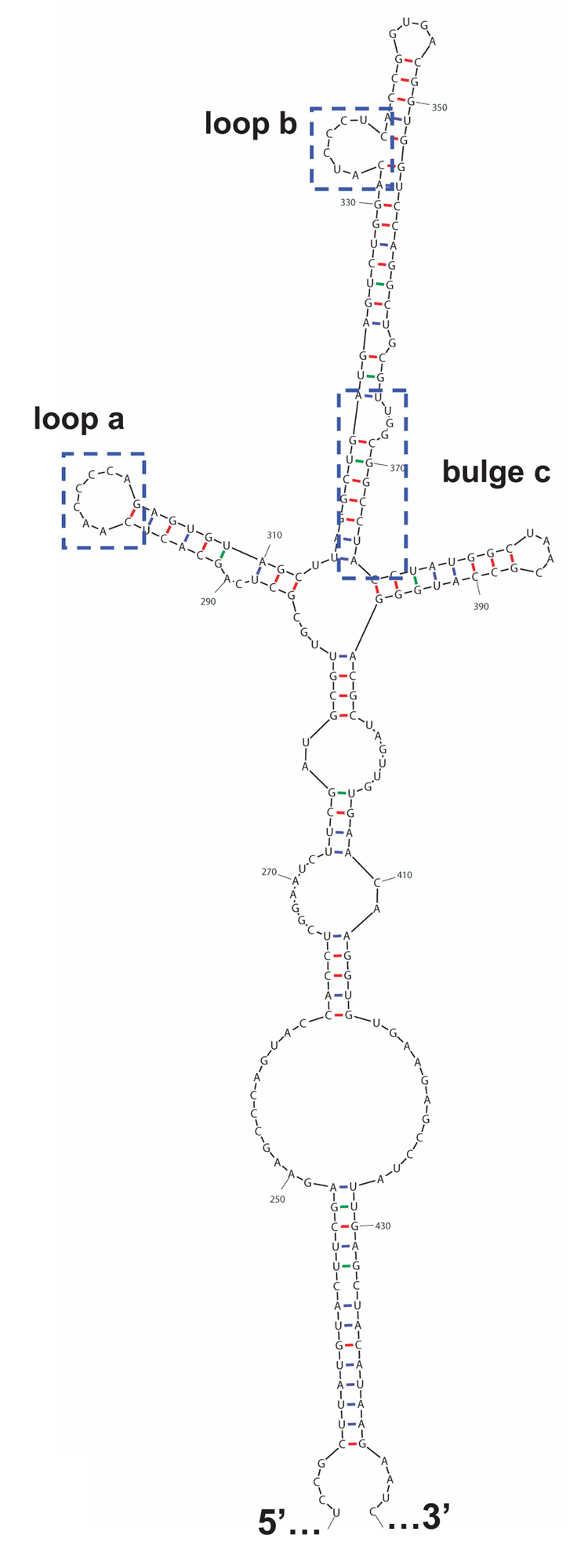

The PCBP2 linker augments binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA

Individually, the KH domains of PCBP1 and PCBP2 fold into a predicted RNA binding motif (Siomi et al., 1993). It has been shown that PCBP2 KH1 is required for binding to poliovirus stem-loop I and IV RNA (Silvera et al., 1999; Walter et al., 2002). Charge-to-alanine mutations made in the PCBP2 KH3 domain reduced binding to poliovirus stem-loop I RNA, but eliminated binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA, suggesting differential KH domain utilization in RNA binding (Walter et al., 2002). We postulated that the observed differences in binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA (refer to the predicted stem-loop IV structure in Fig. 4A) are a result of the linker domain, since this domain has the greatest amino acid differences between the two proteins, including nine extra amino acids in the PCBP2 linker. To test our hypothesis that the PCBP2 linker augments binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Fig. 4B). The mobility shift assays confirmed our previous finding that at low concentrations, PCBP1 is unable to interact with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA, while PCBP2 can bind this RNA (compare Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 3 with 10 and 11, respectively). The PCBP1 linker-containing chimeric proteins, PCBP1-Linker, PCBP1-Linker/KH3, and PCBP1-Linker/P2B, were unable to interact with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA (Fig. 4B, lanes 4–9). All of the PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins interacted with stem-loop IV RNA (Fig. 4B, lanes 12–17). The apparent affinity of wild type PCBP2 for poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA is high, with a KD of 15 nM; so all of the RNA probe was bound using a minimum protein concentration of 50 nM (Gamarnik and Andino, 2000). The relative affinity of PCBP2-Linker/KH3 for poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA (Fig. 4B, lane 14) appears to be reduced, compared to the rest of the PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins; however, the mobility shift assay data with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA (Fig. 2B, lanes 12 and 13) suggest that the overall RNA binding activity of this protein preparation is reduced compared to the other PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins. Taken together, our data from the mobility shift assays demonstrate that the PCBP2 linker is a major determinant for binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA.

Figure 4. The PCBP2 linker mediates binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA.

A. Mfold predicted RNA secondary structure of stem-loop IV. Nucleotide constraints were determined by chemical and enzymatic structure probing (Skinner et al., 1989). The structure shown represents nucleotide 230 to 444 for poliovirus type 1 genomic RNA. Poliovirus stem-loop IV is predicted to form a cruciform-like structure. Loops a and b, and bulge c, boxed, have been identified to interact with PCBP2 (Gamarnik and Andino, 2000). B. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA. In vitro transcribed [32P] UTP-labeled poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA at a final concentration of 1 nM was incubated with 50 or 100 nM of purified recombinant PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins for 10 minutes at 30°C, and the reaction was resolved by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lane 1 shows the electrophoretic mobility of the RNA probe in the absence of added protein. Lanes 2–9 show the incubation of the PCBP1-linker containing chimeric proteins with the RNA. Lanes 10–17 show the formation of ribonucleoprotein complexes by the interaction of the PCBP2-linker containing chimeric proteins with the RNA. The RNP complexes are denoted by the upper arrow.

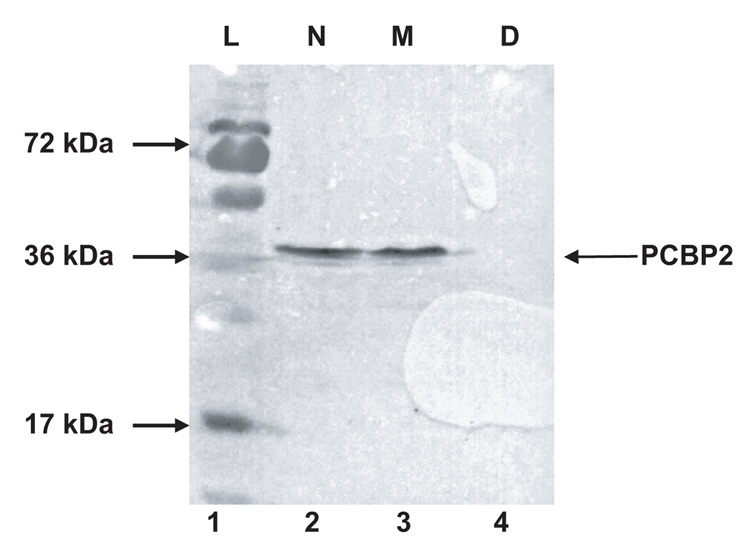

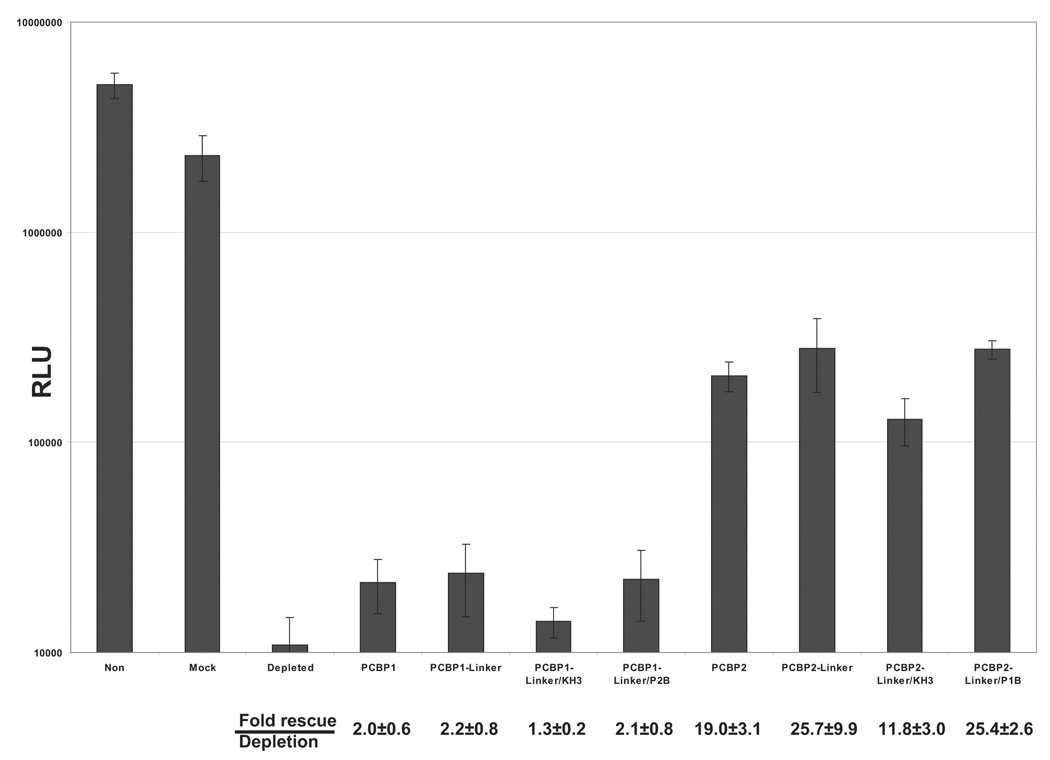

PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins rescue poliovirus IRES-mediated Translation

The interaction of PCBP2 with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA is required for poliovirus IRES-mediated translation (Blyn et al., 1997). Mutations made to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA that inhibit binding to PCBP2 also abrogate IRES-mediated translation (Gamarnik and Andino, 2000). We have previously demonstrated that translation of a reporter RNA in HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extract depleted of PCBPs is inefficient; however, upon addition of recombinant PCBP2, poliovirus IRES-mediated translation can be rescued (Walter et al., 1999; Walter et al., 2002). To determine if the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins can stimulate poliovirus IRES-mediated translation, we performed in vitro translation assays using a reporter RNA in the absence and presence of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins. Translation of the luciferase reporter RNA is driven by the IRES of poliovirus. PCBP was depleted from HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extract via poly(rC)-sepharose affinity chromatography, and depletion was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 5A). Mock depletion of the HeLa S10 were also carried out to control for non-specific depletion of cellular factors that are important in translation. Cap-independent translation of the luciferase reporter RNA in PCBP-depleted HeLa cytoplasmic extract is inefficient [compare mock-depleted to PCBP-depleted (Fig. 5B)]. Addition of PCBP1 linker-containing chimeric proteins to the PCBP-depleted extract caused a slight stimulation of translation (1–2 fold); however, addition of PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins significantly stimulated poliovirus IRES-mediated translation (12–26 fold) (Fig. 5B). The level of rescue varied between the PCBP2-linker containing chimeric proteins, as summarized at the bottom of Fig. 5B. The lower levels of rescue observed for PCBP2-Linker/KH3 might be due to the lower specific activity of that protein preparation that is seen in the mobility shift assays with poliovirus stem-loop I and IV RNAs (refer to Fig. 2B and Fig. 4B). The in vitro translation assays show that PCBP2-linker containing chimeric proteins significantly stimulated translation, supporting previous conclusions that PCBP2 binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA mediates, in part, IRES-dependent translation.

Figure 5. Addition of PCBP2-linker containing chimeric proteins to PCBP-depleted cytoplasmic extracts rescues poliovirus IRES-mediated translation.

A. Western blot analysis of HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extract depleted of PCBP. A total of 50 µg of protein from HeLa cell cytoplasmic extract or HeLa cell cytoplasmic extract depleted of PCBPs via poly(rC)-sepharose affinity chromatography was resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed using a monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody. Lane 1 shows the molecular weight ladder, L. Lanes 2–4 display the non-depleted HeLa S10 (N), mock-depleted HeLa S10 (M) and PCBP-depleted HeLa S10 (D). B. Luciferase assays measuring the in vitro translation of PV 5′ NCR-luc RNA with PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins. We incubated 50 fmol of PV 5′ NCR-luc RNA and 100 nM of PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins in PCBP-depleted HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extract for 2.5 hours at 30°C and assayed for luciferase activity. The relative light unit (RLU) values are averages from three separate reactions. The error bars are standard deviations from the mean.

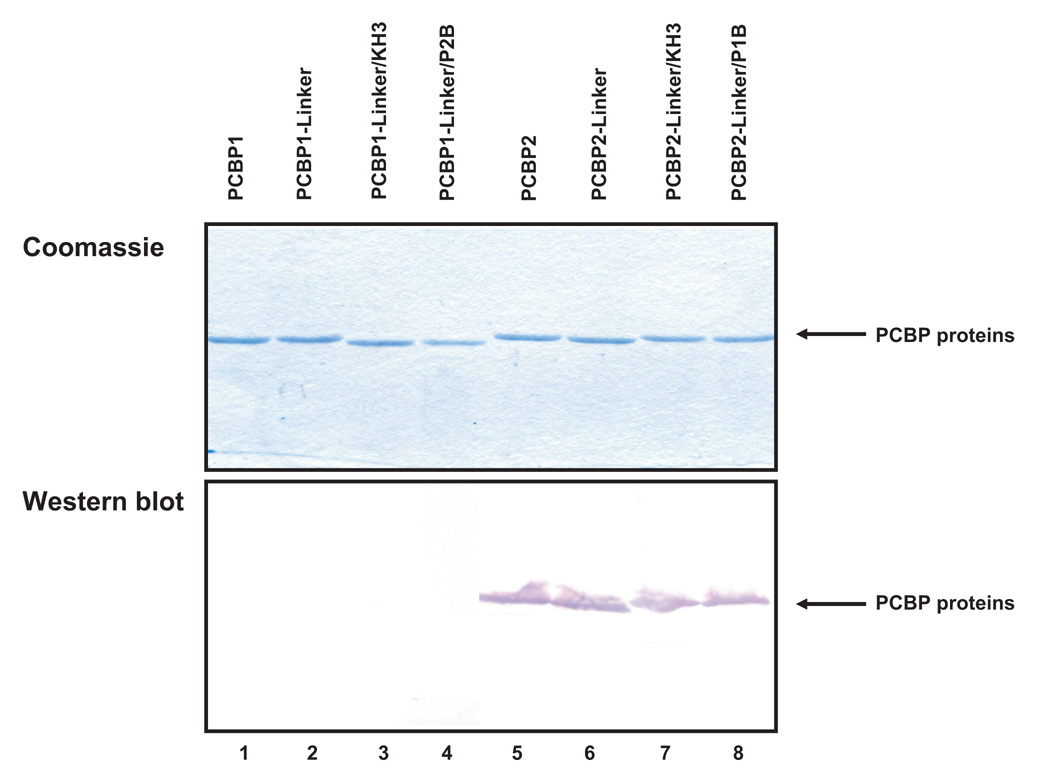

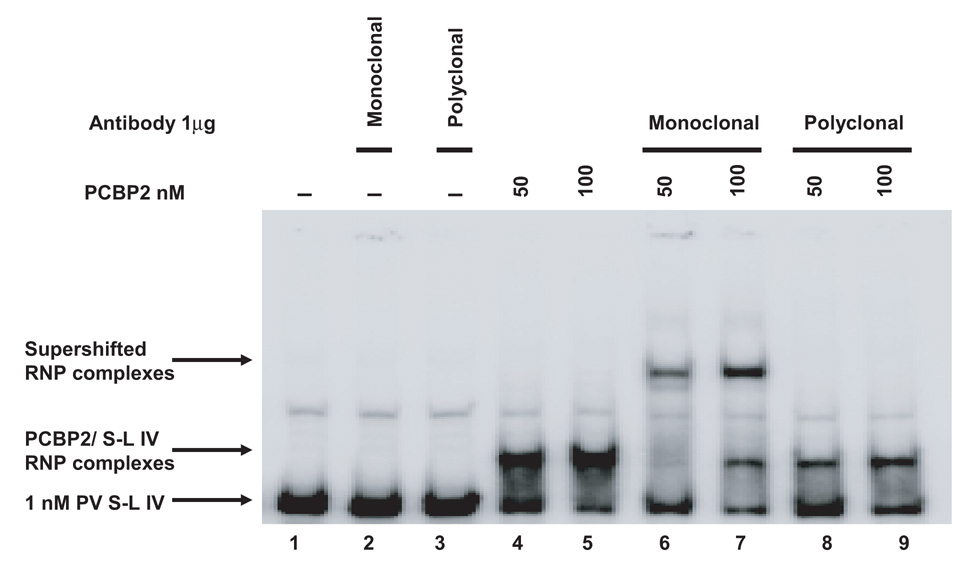

The linker region of PCBP2 does not interact directly with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA

We demonstrated that PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins can bind to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA and stimulate IRES-mediated translation. One possible explanation for how the PCBP2 linker modulates binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA is an increased domain flexibility of the linker due to the extra nine amino acids. We postulate that the increased flexibility of the PCBP2 linker strengthens the RNA-protein interaction of the adjacent KH domains for poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA. To further extend our studies on the PCBP2 linker, we examined the effects of adding a monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody that appears to recognize the PCBP2 linker region (at least in denatured preparations of protein) to our in vitro assays. As a control, we utilized a polyclonal anti-PCBP antibody that is not specific for the PCBP2 linker. The Coomassie-stained, SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins and Western blot analysis using the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody show that the antibody only recognizes wild type PCBP2 and PCBP2 linker-containing chimeric proteins (Fig. 6A), suggesting that amino acid sequences within the PCBP2 linker domain form the major epitope recognized by the monoclonal antibody in denatured preparations of protein. Interestingly, Western blot analysis using the polyclonal anti-PCBP antibody shows that this antibody recognizes wild type PCBP1, PCBP2 and all of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins, indicating that some of the recognized epitopes are shared between PCBP1 and PCBP2 (data not shown). To further dissect the contributions of the PCBP2 linker domain to RNA binding, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays of PCBP2 and poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA in the presence of either the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 or polyclonal anti-PCBP antibodies (Fig. 6B). The purified IgG fractions from these antibodies do not interact with the radio-labeled poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA non-specifically, as expected (Fig. 6B, lanes 2–3); adding increasing amounts of recombinant PCBP2 yielded a dose-dependent increase in RNP complex formation, indicating RNA-protein interaction (Fig. 6B, lanes 4–5). Addition of monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody to mobility shift assays of PCBP2 and poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA resulted in a super-shifted RNP complex (Fig. 6B, lanes 6–7). Addition of the polyclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody failed to super-shift the RNP complex, suggesting that significant numbers of PCBP2 epitopes recognized by this antibody preparation are masked when stem-loop IV-PCBP2 RNP complexes are formed (Fig. 6B, lanes 8–9). We also examined the effect of adding purified IgG corresponding to either monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody or polyclonal anti-PCBP antibody to in vitro translation assays of a poliovirus-IRES reporter RNA in HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extract and found that addition of either antibody had no effect on poliovirus IRES-mediated translation (data not shown). Addition of either monoclonal anti-PCBP2 or polyclonal anti-PCBP antibody to an EMCV IRES-mediated in vitro translation reaction did not inhibit translation, indicating that the antibody did not exert any non-specific inhibitory effects (data not shown). The data from the in vitro assays using the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody showed that PCBP2 can still function in RNA binding and translation stimulation even when the linker is bound by an antibody.

Figure 6. Monoclonal antibody targeting the linker region of PCBP2 does not interfere with binding to stem-loop IV RNA.

A. Purified, recombinant PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins (1 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with coomassie blue (upper panel). Western blot analysis of the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins (lower panel). PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins (1µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with a monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody. Only proteins that contain the PCBP2 linker are detected by the antibody (shown by the arrow). B. Mobility shift assay of recombinant PCBP2 and poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA with the addition of a monoclonal or polyclonal anti-PCBP2 IgG. In vitro transcribed [32P] UTP-labeled poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA at a final concentration of 1 nM was incubated with 50 or 100 nM of purified recombinant PCBP2 for 10 minutes at 30°C. 1 µg of antibody was then added to the reaction and incubated for an additional 10 minutes at 30°C. The reaction was then resolved by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lane 1 is the RNA alone. Lanes 2–3 show the incubation of the RNA in the presence of the monoclonal or polyclonal anti-PCBP2 IgG. Lanes 4–5 show ribonucleoprotein complexes formed by the interaction of PCBP2 with the RNA, as indicated by the PCBP2/ stem-loop IV RNP complexes arrow. Lanes 6–7 show the super-shifted RNP complex mediated by the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody, as indicated by the super-shifted RNP complex arrow. Lanes 8–9 show that the polyclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody did not super-shift the PCBP2-poliovirus stem-loop IV RNP complex.

Discussion

During a poliovirus infection, the viral proteinase 2A cleaves eIF4G and poly(A) binding protein (PABP), a binding partner of eIF4G that interacts with the 3’ poly(A) tract of cellular mRNAs to functionally circularize the template for synergistic enhancement of translation (Tarun and Sachs, 1996). These cleavage events lead to the inhibition of cap-dependent translation (Kräusslich et al., 1987; Gradi et al., 1998; Joachims et al., 1999; Kerekatte et al., 1999; Liebig et al., 2002). Poliovirus is not affected by this shut down of cap-dependent translation because it utilizes an IRES-mediated translation mechanism (Pelletier and Sonenberg, 1988). IRES-mediated translation also occurs for some cellular mRNAs, which may be a mechanism to ensure expression of vital proteins during situations of reduced cap-dependent translation (in addition to viral infection), such as hypoxia, amino acid starvation, and cell cycling. Consistent with this, the majority of cellular IRESes discovered so far mediate the translation of proteins involved in cell progression, differentiation, or apoptosis (Stoneley and Willis, 2004). With an alternative translation mechanism already in place in human cells, infection by poliovirus exploits cellular components to its own advantage. The utilization of PCBP2 and PCBP1 by poliovirus to mediate important viral functions such as translation and RNA replication is not surprising, considering the multi-functional properties of the PCBPs, resulting from their ability to interact with both nucleic acids and proteins.

Previously, Dejgaard and Leffers showed that individually-expressed KH1 and KH3 domains of PCBP1 and PCBP2 had high affinity and broad specificity for RNA substrates in vitro (Dejgaard and Leffers, 1996). They also presented data showing that the KH2 domain from either protein exhibited poor RNA binding activity. In another study, when individual KH domains of PCBP2 were expressed, only KH1 was able to interact with both poliovirus stem-loop I and IV RNAs in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Silvera et al., 1999). It was also shown that charge-to-alanine mutations in amino acids of KH1 or KH3 predicted to interact with RNA eliminated binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA (Walter et al., 2002). Taken together, these results suggested that the correct amino sequences and intact KH domains of PCBP2 are required for proper protein folding and binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA.

As noted above, PCBP1 and PCBP2 have distinct functions in the in the poliovirus life cycle. While both PCBP1 and PCBP2 interact with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA and mediate, in part, negative strand RNA synthesis, only PCBP2 binds to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA with high affinity, an interaction required for cap-independent translation. Due to the amino acid differences that exist in the linker region between PCBP1 and PCBP2, including nine extra amino acids PCBP2 linker, we predicted that the linker region of PCBP2 is the domain responsible for the ability to bind to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA. The observed binding differences may, in part, be attributed to the secondary structure of the target RNA sequences. The secondary structure of poliovirus stem-loop I RNA presents two potential PCBP binding sites, stem-loop b and the c-rich spacer sequence (Fig. 2A) (Gamarnik and Andino, 1997; Parsley et al., 1997; Toyoda et al., 2007). The interactions of PCBP2 with these binding sites require just two KH domains (Walter et al., 2002; Perera et al., 2007). In the case of poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA, the RNA secondary structure is more extensive and presents three potential PCBP2 binding sites. RNase foot-printing analysis of PCBP2 with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA revealed three regions of the RNA, loop a, loop b and bulge c that are protected by PCBP2 (Fig. 4A) (Gamarnik and Andino, 2000). We speculate that the interaction of PCBPs with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA requires three KH domains and that each region of the RNA may interact with an individual KH domain of PCBP2. However, since PCPB2 is known to dimerize, the exact number of PCBP2 molecules required to interact with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA has yet to be determined. We suggest that the nine extra amino acids of the PCBP2 linker domain (compared to PCBP1) extends this region and allows greater structural flexibility to accommodate the interactions of KH2 and KH3 with the RNA. Such flexibility may strengthen the overall interaction of the protein with the RNA. For PCBP1, we predict that the shorter, more rigid linker domain does not allow optimal binding of the KH2 and/or KH3 domains with the respective RNA motifs to poliovirus stem-loop IV.

In this report, we have presented evidence that the linker region of PCBP2 is the domain responsible for its increased binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA compared to PCBP1 interacting with the same RNA. Initially, via electrophoretic mobility shift assays with poliovirus stem-loop I RNA and GST-pull-downs with GST-PCBP2, we showed that the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins (except PCBP1-Linker/P2B) were active in RNA binding, and all six were active in protein-protein interactions. The electrophoretic mobility shift assays with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA clearly showed that only PCBP2 linker-containing PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins were able to interact with the RNA. Data from our in vitro translation experiments using HeLa cell cytoplasmic extracts depleted of PCBP showed that only addition of PCBP2 linker-containing PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins rescued poliovirus IRES-mediated translation. The electrophoretic mobility shift assays using the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody showed that the PCBP2 linker augments binding to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA via a mechanism that is not inhibited by addition of an antibody specific to the linker domain. The super-shifted RNP complex observed in the mobility shift assay supports our hypothesis that the nine additional amino acids of the PCBP2 linker allow steric flexibility because even when complexed with the RNA, the linker is presented in a way that is able to be recognized by the antibody.

Our in vitro translation assays revealed that the addition of either a monoclonal anti-PCBP2 or a polyclonal anti-PCBP antibody did not inhibit poliovirus IRES-mediated translation (data not shown). We did not expect the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody to inhibit poliovirus translation, because the mobility shift assay showed that even when it is complexed with the antibody, PCBP2 can still bind to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA. For the polyclonal anti-PCBP antibody, we predicted that the antibody-recognizes epitope(s) that overlap with an RNA binding domain, so the antibody might inhibit translation; however, this was not observed. A possible explanation for the lack of translation inhibition might be due to the presence of multiple epitopes recognized by the polyclonal antibody that do not interfere with the activity of the protein. Taken together, the data from these experiments clearly support our hypothesis that the PCBP2 linker is the domain responsible for the differential ability of PCBP2 to bind poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA and subsequently mediate cap-independent translation of the viral genome.

Finally, to further verify our hypothesis that the differential binding activity to poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA is due to the PCBP2 linker, it will be important to identify other RNA secondary structures that display differential binding affinities for PCBP1 and PCBP2. The observed binding differences between PCBP1 and PCBP2 on RNA secondary structures may potentially be a broader mechanism regulating stability or translation inhibition of cellular mRNAs. Ultimately, co-crystallization structures of intact PCBP1 and PCBP2 with poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA will be required to define the direct interaction between these proteins and the RNA.

Materials and methods

Plasmid design

PCBP1 and PCBP2 sequences were cloned into pET22 expression vector from pQE30-PCBP1 and pQE30-PCBP2 (Blyn et al., 1996) by PCR amplification using N-terminal and C-terminal primers with NdeI and XhoI restriction sites respectively. PCR site-directed mutagenesis was carried out to introduce silent NheI and XhoI restrictions sites in the KH2/Linker and Linker/KH3 interface respectively. PCBP1-Linker and PCBP2-Linker proteins were generated by exchanging the cleavage products of NdeI and NheI digestion of pET22-PCBP1 and pET22-PCBP2. PCBP1-Linker/KH3 and PCBP2-Linker/KH3 proteins were generated by digestion of pET22-PCBP1 and pET22-PCBP2. PCBP1-Linker/P2B and PCBP2-Linker/P1B were generated by exchanging the cleavage products of XhoI digestion of PCBP1-Linker and PCBP2-Linker.

Protein purification

The pET22-PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL-21 cells. We inoculated 1 liter of M9 media with 1 ml of overnight culture. The cells were grown at 37°C until the culture reached an absorbance of OD600= 0.2. Protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG. The bacteria were grown for an additional 3 hrs at 18°C and then pelleted by centrifugation. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 20 ml of phosphate buffer (50 mM phosphate pH 7.0, 5% glycerol, and 300 mM NaCl) and lysed by sonication. The supernatant was adjusted to 20% ammonium sulfate and centrifuged to pellet the protein precipitate. The ammonium sulfate precipitate was resuspended in 10 ml of phosphate buffer and dialyzed overnight against 1 L of phosphate buffer. The protein was batch bound in 1 ml of bed volume of Ni2+ sepharose resin (Amersham). The resin was loaded onto a column and washed with 50 ml of 20 mM imidazole-phosphate buffer and eluted with 200 mM imidazole-phosphate buffer. The proteins were dialyzed in initiation buffer (5 mM Tris-Cl, 25 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.05 mM EDTA and 5% glycerol) prior to use in mobility shift assays or in vitro translation assays.

HeLa S10 preparation

The HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extracts were prepared with slight modifications following the protocol published in Barton and Flanegan, 1993. Briefly, 6 liters of HeLa suspensions cells were pelleted and resuspended in wash buffer (35 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 146 mM NaCl and 11 mM glucose) and re-pelleted. The HeLa cell pellet was then resuspended in hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgOAc, and 1 mM DTT) and allowed to swell for 20 minutes. Cells were lysed by Dounce homogenization, and the extract was adjusted by adding 1/10 of the extract volume of post-lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 120 mM KOAc, 4 mM MgOAc, and 5 mM DTT). CaCl2 (1mM) and micrococcal nuclease (2 mg/ml) were added and incubated for 15 minutes at 14°C, followed by addition of EGTA (4 mM). The extract was stored in liquid N2.

PCBP depletion

The HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extracts were depleted of PCBP by RNA affinity chromatography, as described (Walter et al., 1999). Depletion of PCBP from the extract was verified by Western Blot analysis using the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody. The PCBP-depleted extracts were stored in liquid N2. Mock-depleted extracts were generated as described (Walter et al., 1999).

Antibody purification

The IgG fraction from polyclonal PCBP antibodies was purified from the serum using DEAE-Affigel-Blue (Bio-Rad) chromatography. Briefly, rabbit serum was loaded onto the column in starting buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 and 25 mM NaCl) and the IgG fractions were eluted with the same buffer. Pooled peak protein fractions were adjusted to 50% ammonium sulfate for precipitation. The ammonium sulfate precipitate was resuspended in 1 ml of initiation buffer and dialyzed in the same buffer. Production of the monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody was carried out by Cell Essentials (Boston). The IgG was purified from the hybridoma supernatant under the same conditions as described above for the polyclonal antibody.

In vitro transcription

Radio-labeled poliovirus RNAs were generated by in vitro T7 polymerase (New England) transcription using [32P] labeled UTP (GE Health Sciences). The poliovirus stem-loop I and IV transcription templates were generated by DdeI digestion of pT7-PV1 and HindIII digested pT220-460, respectively. Poliovirus stem-loop I RNA was purified by resolving the transcription reaction using electrophoresis in an 8% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 6 M urea. Radio-labeled poliovirus stem-loop I RNA was excised from the gel and eluted with oligo elution buffer (500 mM NH4OAc, 1 mM EDTA and 0.1% SDS). The eluent was subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Poliovirus stem-loop IV RNA was purified by Chromaspin chromatography (Clonetech), phenol/chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation.

Mobility shift assays

PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins were pre-incubated (at a final concentration of 50 or 100 nM) with BSA (1mg/ml), yeast tRNA (0.8 mg/ml) and binding buffer (5 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 4% glycerol) up to a volume of 9 µl for 10 minutes at 30°C. Then 1 µl of radio-labeled poliovirus stem-loop I or IV RNA (at a final concentration of 1 or 0.1 nM) was added and the reaction was incubated for an additional 10 minutes at 30°C. The reaction was adjusted with 10% glycerol and resolved by native glycerol-polyacrylamide (4%) gel electrophoresis.

GST-pulldown assays

GST-PCBP2 protein was expressed and purified using the same conditions as described for the PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins except that it was affinity purified by using Glutathione-sepharose 4B (Amersham). The pulldown assays consisted of 100 µl 50% glutathione-sepharose 4B, 1 µg GST-PCBP2, and 2.5 µg of µPCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric proteins (up to a total volume of 200 µl) incubated on ice for 1 hour (vortexed at 20 minute intervals). For the GST control, we used 0.4 µg GST per reaction. The reactions were then pelleted by centrifugation for 2 min. at 3000xg and washed three times in TENN buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl and 0.5% NP-40). The GST-pulldown reactions were resolved by 12.5 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by silver staining.

In vitro translation assay and luciferase assay

The in vitro translation reactions were carried out according to Walter et al., 1999. Briefly, the translation reaction consisted of 60% HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extract, 1 µl of all-4-mix (1 mM ATP, 250 µM CTP, 250 µM GTP, and 250 µM UTP, 16 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 60 mM KOAc, 30 mM creatine-phosphate, and 400 µg creatine kinase), 50 fmol of PV 5’NCR-luciferase RNA, 100 nM PCBP1/PCBP2 chimeric protein, and initiation buffer for a total volume of 10 µl. The reaction was incubated for 2.5 hours at 30°C. Translation was stopped by addition of 10 µl of passive lysis buffer (Promega). Translation efficiency was determined by measuring the light emission of 10 µl of the total in vitro translation reaction in 50 µl of luciferin substrate (Promega) in a luminometer (Berthold).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kerry D. Fitzgerald and Sarah Daijogo for critical comments and helpful suggestions on the manuscript and to Sarah Daijogo for helpful experimental discussions. We also thank MyPhuong Tran for preparation of HeLa S10 cytoplasmic extracts, Janet M. Rozovics for GST protein, and Kerry D. Fitzgerald for column-purified monoclonal anti-PCBP2 antibody. This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI 26765 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andino R, Rieckhof GE, Baltimore D. A functional ribonucleoprotein complex forms around the 5' end of poliovirus RNA. Cell. 1990;63:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90170-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton DJ, Flanegan JB. Coupled translation and replication of poliovirus RNA in vitro: synthesis of functional 3D polymerase and infectious virus. J Virol. 1993;67:822–831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.822-831.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard KM, Daijogo S, Semler BL. A nucleo-cytoplasmic SR protein functions in viral IRES-mediated translation initiation. EMBO J. 2007;26:459–467. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard KM, Walter BL, Semler BL. Multimerization of poly(rC) binding protein 2 is required for translation initiation mediated by a viral IRES. RNA. 2004;10:1266–1276. doi: 10.1261/rna.7070304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsham GJ, Sonenberg N. RNA-protein interactions in regulation of picornavirus RNA translation. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:499–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.499-511.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyn LB, Chen R, Semler BL, Ehrenfeld E. Host cell proteins binding to domain IV of the 5' noncoding region of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 1995;69:4381–4389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4381-4389.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyn LB, Swiderek KM, Richards O, Stahl DC, Semler BL, Ehrenfeld E. Poly(rC) binding protein 2 binds to stem-loop IV of the poliovirus RNA 5' noncoding region: identification by automated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:11115–11120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyn LB, Towner JS, Semler BL, Ehrenfeld E. Requirement of poly(rC) binding protein 2 for translation of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 1997;71:6243–6246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6243-6246.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejgaard K, Leffers H. Characterisation of the nucleic-acid-binding activity of KH domains. Different properties of different domains. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;241:425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Lee JK, Fenn S, Tjhen R, Stroud RM, James TL. X-ray crystallographic and NMR studies of protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions involving the KH domains from human poly(C)-binding protein-2. RNA. 2007;13:1043–1051. doi: 10.1261/rna.410107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Yu J, Chen Y, Andino R, James TL. Specific recognition of the C-rich strand of human telomeric DNA and the RNA template of human telomerase by the first KH domain of human poly(C)-binding protein-2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48126–48134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Mitchell SA, Spriggs KA, Ostrowski J, Bomsztyk K, Ostarek D, Willis AE. Members of the poly (rC) binding protein family stimulate the activity of the c-myc internal ribosome entry segment in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2003;22:8012–8020. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn S, Du Z, Lee JK, Tjhen R, Stroud RM, James TL. Crystal structure of the third KH domain of human poly(C)-binding protein-2 in complex with a C-rich strand of human telomeric DNA at 1.6 A resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2651–2660. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke B, Zuleger B, Benavente R, Schuster T, Goller M, Stevenin J, Horak I. The mouse poly(C)-binding protein exists in multiple isoforms and interacts with several RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acid Res. 1996;24:3821–3828. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.19.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarnik AV, Andino R. Two functional complexes formed by KH domain containing proteins with the 5’ noncoding region of poliovirus RNA. RNA. 1997;3:882–892. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarnik AV, Andino R. Interactions of viral protein 3CD and poly(rC) binding protein with the 5' untranslated region of the poliovirus genome. J. Virol. 2000;74:2219–2226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2219-2226.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradi A, Svitkin YV, Imataka H, Sonenberg N. Proteolysis of human eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4GII, but not eIF4GI, coincides with the shutoff of host protein synthesis after poliovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci .U. S .A. 1998;95:11089–11094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SL, Hsuan JJ, Totty N, Jackson RJ. Unr, a cellular cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein with five cold-shock domains, is required for internal initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA. Genes Dev. 1999;13:437–448. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SK, Krausslich HG, Nicklin MJ, Duke GM, Palmenberg AC, Wimmer E. A segment of the 5' nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J. Virol. 1988;62:2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2636-2643.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SK, Wimmer E. Cap-independent translation of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA: structural elements of the internal ribosomal entry site and involvement of a cellular 57-kD RNA-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1560–1572. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachims M, Van Breugel PC, Lloyd RE. Cleavage of poly(A)-binding protein by enterovirus proteases concurrent with inhibition of translation in vitro. J. Virol. 1999;73:718–727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.718-727.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerekatte V, Keiper BD, Badorff C, Cai A, Knowlton KU, Rhoads RE. Cleavage of poly(A)-binding protein by coxsackievirus 2A protease in vitro and in vivo: another mechanism for host protein synthesis shutoff? J. Virol. 1999;73:709–717. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.709-717.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Hahm B, Kim YK, Choi M, Jang SK. Protein-protein interaction among hnRNPs shuttling between nucleus and cytoplasm. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:395–405. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kräusslich HG, Nicklin MJ, Toyoda H, Etchison D, Wimmer E. Poliovirus proteinase 2A induces cleavage of eucaryotic initiation factor 4F polypeptide p220. J. Virol. 1987;61:2711–2718. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.9.2711-2718.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebig HD, Seipelt J, Vassilieva E, Gradi A, Kuechler E. A thermosensitive mutant of HRV2 2A proteinase: evidence for direct cleavage of eIF4GI and eIF4GII. FEBS Lett. 2002;523:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02933-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeyev AV, Liebhaber SA. The poly(C)-binding proteins: a multiplicity of functions and a search for mechanisms. RNA. 2002;8:265–278. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202024627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Michael WM, Dreyfuss G. Characterization and primary structure of the poly(C) binding protein heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex K protein. Mol Cell. Biol. 1992;12:164–171. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick WC. Overview: mechanism of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Enzyme. 1990;44:7–16. doi: 10.1159/000468743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KE, Roberts AW, Barton DJ. Poly(rC) binding proteins mediate poliovirus mRNA stability. RNA. 2001;7:1126–1141. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201010044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostareck DH, Ostareck-Lederer A, Wilm M, Thiele BJ, Mann M, Hentze MW. mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: hnRNP K and hnRNP E1 regulate 15-lipoxygenase translation from the 3' end. Cell. 1997;89:597–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsley TB, Towner JS, Blyn LB, Ehrenfeld E, Semler BL. Poly (rC) binding protein 2 forms a ternary complex with the 5'- terminal sequences of poliovirus RNA and the viral 3CD proteinase. RNA. 1997;3:1124–1134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J, Sonenberg N. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature. 1988;334:320–325. doi: 10.1038/334320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera R, Daijogo S, Walter BL, Nguyen JH, Semler BL. Cellular protein modification by poliovirus: the two faces of poly(rC)-binding protein. J. Virol. 2007;81:8919–8932. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01013-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvera D, Gamarnik AV, Andino R. The N-terminal K homology domain of the poly(rC)-binding protein is a major determinant for binding to the poliovirus 5'-untranslated region and acts as an inhibitor of viral translation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:38163–38170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi H, Matunis MJ, Michael WM, Dreyfuss G. The pre-mRNA binding K protein contains a novel evolutionarily conserved motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1193–1198. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MA, Racaniello VR, Dunn G, Cooper J, Minor PD, Almond JW. New model for the secondary structure of the 5′ non-coding RNA of poliovirus is supported by biochemical and genetic data that also show that RNA secondary structure is important in neurovirulence. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;207:379–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonely M, Willis AE. Cellular internal ribosome entry segments: structures, transacting factors and regulation of gene expression. Oncogene. 2004;23:3200–3207. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun SZ, Sachs AB. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda H, Franco D, Fujita K, Paul AV, Wimmer E. Replication of poliovirus requires binding of the poly(rC) binding protein to the cloverleaf as well as to the adjacent C-rich spacer sequence between the cloverleaf and the internal ribosomal entry site. J. Virol. 2007;81:10017–10028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00516-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter BL, Nguyen JH, Ehrenfeld E, Semler BL. Differential utilization of poly(rC) binding protein 2 in translation directed by picornavirus IRES elements. RNA. 1999;5:1570–1585. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter BL, Parsley TB, Ehrenfeld E, Semler BL. Distinct poly(rC) binding protein KH domain determinants for poliovirus translation initiation and viral RNA replication. J. Virol. 2002;76:12008–12022. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12008-12022.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Day N, Trifillis P, Kiledjian M. An mRNA stability complex functions with poly(A)-binding protein to stabilize mRNA in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4552–4560. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss IM, Liebhaber SA. Erythroid cell-specific mRNA stability elements in the alpha 2-globin 3' nontranslated region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:2457–2465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]