Abstract

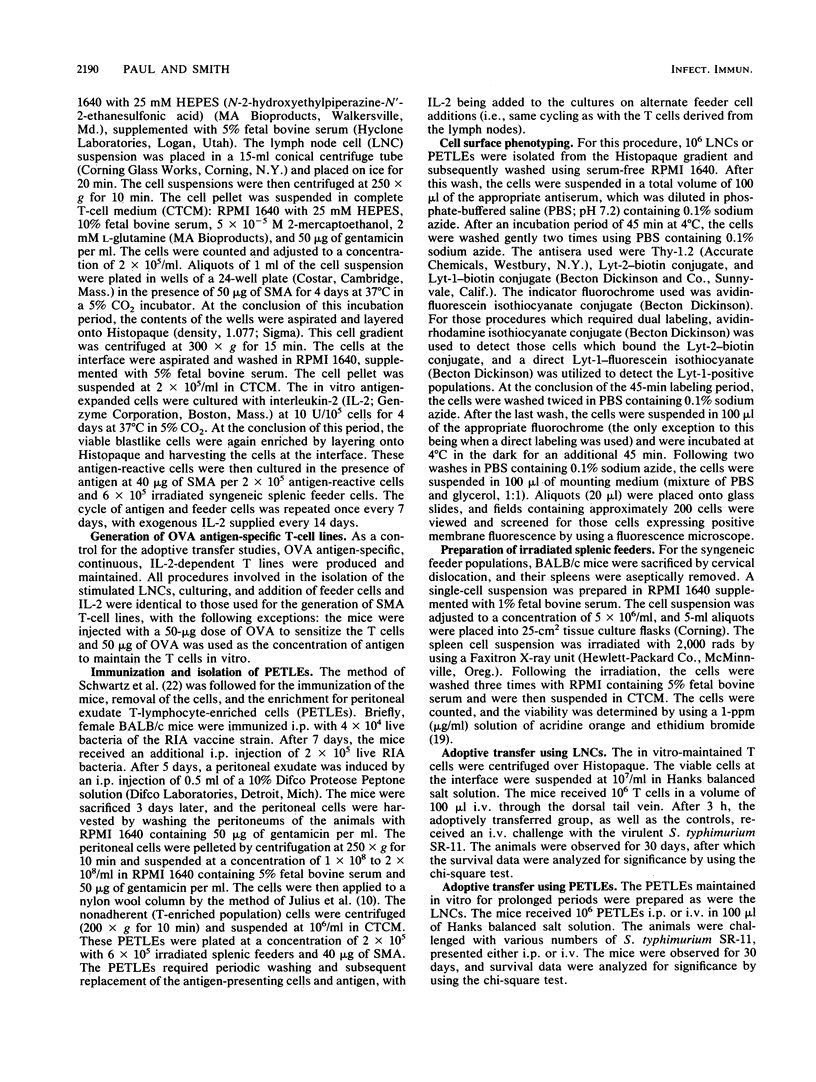

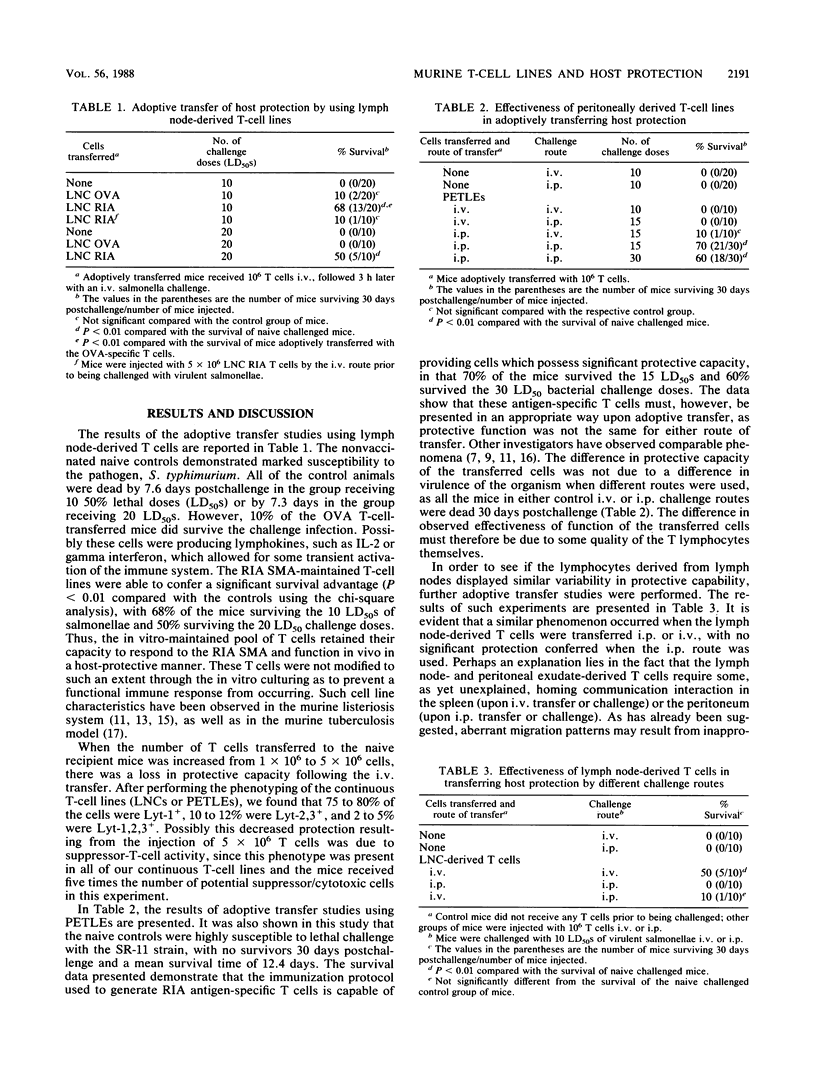

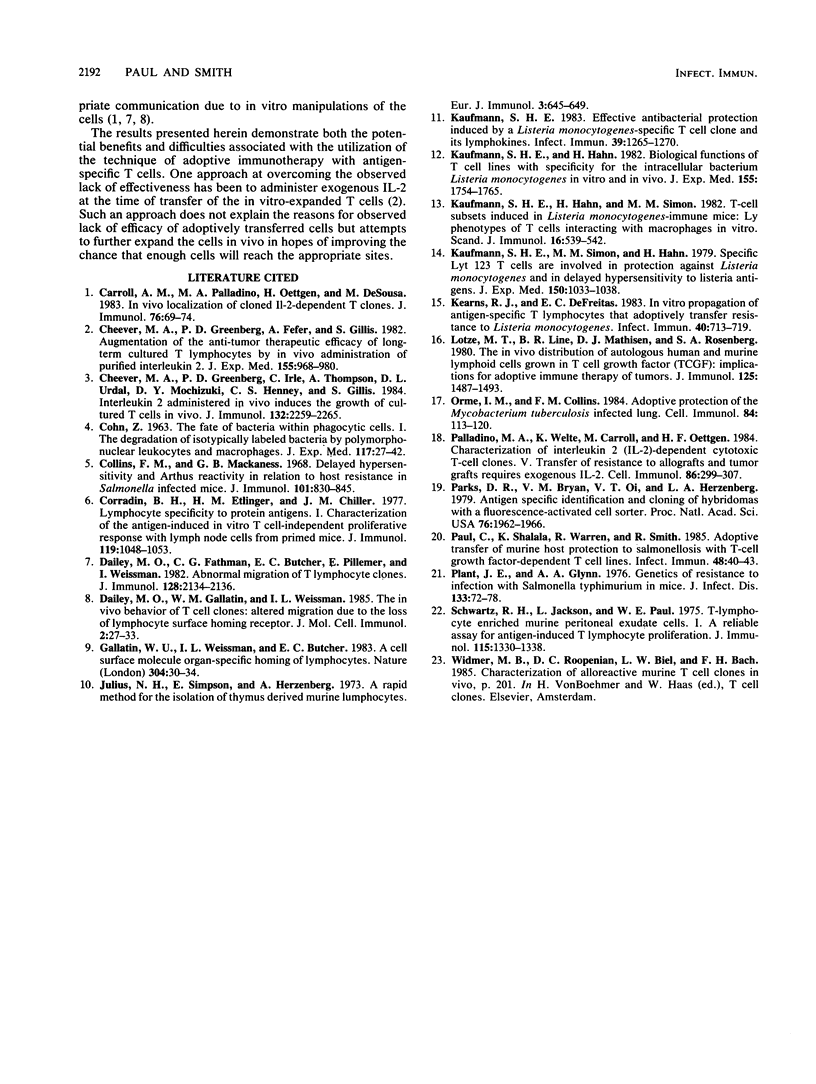

We have demonstrated in this study that long-term, interleukin-2 (IL-2)-dependent, salmonella antigen-specific T-lymphocyte lines, as well as peritoneal exudate-enriched T cells, could be developed from both the antigen-sensitized inguinal and periaortic lymph nodes. Only those lines (salmonella-specific lymph node cells or peritoneal exudate T cells) were capable of adoptively transferring significant host protection (P less than 0.01) compared with the immune reactions of lethally challenged naive controls or of mice that had ovalbumin-specific T-cell lines transferred. Of particular interest was the finding that IL-2-dependent T-cell lines derived from the lymph nodes could only confer host protection to naive mice when both the transfer and challenge dose were administered via the intravenous route. Likewise, those T-cell lines derived from the peritoneal exudate were only capable of adoptively transferring significant protection when the cells and challenge dose of salmonellae were administered intraperitoneally. These studies indicate that systemic host protection can be transferred to naive mice, but depending on the source, the IL-2-dependent T-cell lines (lymph node or peritoneally isolated) functioned differentially upon challenge. Also, the results of this study indicate that the administration of greater numbers of IL-2-specific T cells may result in decreased, rather than enhanced, host protection. This may be due to the fact that the IL-2-dependent T-cell population consisted of 20 to 25% Lyt-2,3+ cells, indicating that cells of the suppressor/cytotoxic phenotype were present. Thus, increasing the number of cells transferred may result in an abrogation of protection.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- COHN Z. A. The fate of bacteria within phagocytic cells. I. The degradation of isotopically labeled bacteria by polymorphonuclear leucocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1963 Jan 1;117:27–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.117.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. M., Palladino M. A., Oettgen H., De Sousa M. In vivo localization of cloned IL-2-dependent T cells. Cell Immunol. 1983 Feb 15;76(1):69–80. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(83)90349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever M. A., Greenberg P. D., Fefer A., Gillis S. Augmentation of the anti-tumor therapeutic efficacy of long-term cultured T lymphocytes by in vivo administration of purified interleukin 2. J Exp Med. 1982 Apr 1;155(4):968–980. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever M. A., Greenberg P. D., Irle C., Thompson J. A., Urdal D. L., Mochizuki D. Y., Henney C. S., Gillis S. Interleukin 2 administered in vivo induces the growth of cultured T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 1984 May;132(5):2259–2265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Mackaness G. B. Delayed hypersensitivity and arthus reactivity in relation to host resistance in salmonella-infected mice. J Immunol. 1968 Nov;101(5):830–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradin G., Etlinger H. M., Chiller J. M. Lymphocyte specificity to protein antigens. I. Characterization of the antigen-induced in vitro T cell-dependent proliferative response with lymph node cells from primed mice. J Immunol. 1977 Sep;119(3):1048–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey M. O., Fathman C. G., Butcher E. C., Pillemer E., Weissman I. Abnormal migration of T lymphocyte clones. J Immunol. 1982 May;128(5):2134–2136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey M. O., Gallatin W. M., Weissman I. L. The in vivo behavior of T cell clones: altered migration due to loss of the lymphocyte surface homing receptor. J Mol Cell Immunol. 1985;2(1):27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallatin W. M., Weissman I. L., Butcher E. C. A cell-surface molecule involved in organ-specific homing of lymphocytes. Nature. 1983 Jul 7;304(5921):30–34. doi: 10.1038/304030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius M. H., Simpson E., Herzenberg L. A. A rapid method for the isolation of functional thymus-derived murine lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1973 Oct;3(10):645–649. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830031011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H. Effective antibacterial protection induced by a Listeria monocytogenes-specific T cell clone and its lymphokines. Infect Immun. 1983 Mar;39(3):1265–1270. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1265-1270.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H., Hahn H. Biological functions of t cell lines with specificity for the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 1982 Jun 1;155(6):1754–1765. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.6.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H., Hahn H., Simon M. M. T-cell subsets induced in Listeria monocytogenes-immune mice. Ly phenotypes of T cells interacting with macrophages in vitro. Scand J Immunol. 1982 Dec;16(6):539–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1982.tb00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H., Simon M. M., Hahn H. Specific Lyt 123 cells are involved in protection against Listeria monocytogenes and in delayed-type hypersensitivity to listerial antigens. J Exp Med. 1979 Oct 1;150(4):1033–1038. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns R. J., DeFreitas E. C. In vitro propagation of antigen-specific T lymphocytes that adoptively transfer resistance to Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1983 May;40(2):713–719. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.713-719.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze M. T., Line B. R., Mathisen D. J., Rosenberg S. A. The in vivo distribution of autologous human and murine lymphoid cells grown in T cell growth factor (TCGF): implications for the adoptive immunotherapy of tumors. J Immunol. 1980 Oct;125(4):1487–1493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme I. M., Collins F. M. Adoptive protection of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected lung. Dissociation between cells that passively transfer protective immunity and those that transfer delayed-type hypersensitivity to tuberculin. Cell Immunol. 1984 Mar;84(1):113–120. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino M. A., Welte K., Carroll A. M., Oettgen H. F. Characterization of interleukin 2 (IL-2)-dependent cytotoxic T-cell clones. V. Transfer of resistance to allografts and tumor grafts requires exogenous IL-2. Cell Immunol. 1984 Jul;86(2):299–307. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D. R., Bryan V. M., Oi V. T., Herzenberg L. A. Antigen-specific identification and cloning of hybridomas with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Apr;76(4):1962–1966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul C., Shalala K., Warren R., Smith R. Adoptive transfer of murine host protection to salmonellosis with T-cell growth factor-dependent, Salmonella-specific T-cell lines. Infect Immun. 1985 Apr;48(1):40–43. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.1.40-43.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant J., Glynn A. A. Genetics of resistance to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J Infect Dis. 1976 Jan;133(1):72–78. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. H., Jackson L., Paul W. E. T lymphocyte-enriched murine peritoneal exudate cells. I. A reliable assay for antigen-induced T lymphocyte proliferation. J Immunol. 1975 Nov;115(5):1330–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]