Abstract

Mammalian cells undergo cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage through multiple checkpoint mechanisms. One such checkpoint pathway maintains genomic integrity by delaying mitotic progression in response to genotoxic stress. Transition though the G2 phase and entry into mitosis is considered to be regulated primarily by cyclin B1 and its associated catalytically active partner Cdk1. While not necessary for its initiation, the p130 and Rb-dependent target genes have emerged as being important for stable maintenance of a G2 arrest. It was recently demonstrated that by interacting with p130, E2F4 is present in the nuclei and plays a key role in the maintenance of this stable G2 arrest. Increased E2F4 levels and its translocation to the nucleus following genotoxic stress result in downregulation of many mitotic genes and as a result promote a G0-like state. Irradiation of E2F4-depleted cells leads to enhanced cellular DNA double-strand breaks that may be measured by comet assays. It also results in cell death that is characterized by caspase activation, sub-G1 and sub-G2 DNA content, and decreased clonogenic cell survival. Here we review these recent findings and discuss the mechanisms of G2 phase checkpoint activation and maintenance with a particular focus on E2F4.

Keywords: E2F4, p130, Rb, G2-phase, cell cycle, mitosis, ionizing radiation, genotoxic stress

Initiating A G2 Checkpoint: The Main Players

In response to DNA damage, such as that caused by ionizing radiation, the most prominent arrest is in the G2 phase,1 which occurs particularly in tumor cells that almost invariably lack an effective G1 arrest. In normal, nontransformed cells that have a functional p53 pathway, both a G1 and a G2 arrest can take place in response to DNA damage.2,3 It has been established that the G2 checkpoint initiation is primarily regulated through the control of Cdk1 (Cdc2) activity, which is regulated at multiple levels (Fig. 1), including periodic association with the B-type cyclins, reversible phosphorylation, and intracellular compartimentalization.4 Cyclin B1, the prototypical cyclin B (B2 and B3 are less abundant) reaches maximum levels in G2, when it enters into the nucleus to form a complex with Cdk1 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner.5 The complex is activated by phosphorylation of Cdk1 on threonine 161 (T161) by Cdk-activating kinase (CAK), but is kept inactive by its phosphorylation on threonine 14 (T14) and tyrosine 15 (Y15) by the Myt1 and Wee1 kinases, respectively.6

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the G2 checkpoint. Cdk1 is the key control point for G2 checkpoint initiation, which is dependent on both positive and negative regulators. To be active, Cdk1 requires binding of its catalytic partner, cyclin B1 (also B2 and B3 in some circumstances), which is regulated transcriptionally and by its nuclear localization. Cdk1 is regulated by its phosphorylation, as determined by a balance of kinase and phosphatase activities, as well as at the level of transcription. G2 progression to mitosis is triggered by the Cdc25C (or B)-mediated dephosphorylation of the Cyclin B/Cdk1 complex. Cyclin B/Cdk1 is activated by phosphorylation of T161 by CAK (Cyc H/Cdk7 complex) and the dephosphorylation of T14 and Y15 by Cdc25C. The complex is kept in an inactive state due to the phosphorylation of T14 and Y15 by the Myt1 and Wee1 kinases that can in turn be regulated by Plk1. The stable maintenance of the G2 arrest is determined by the activity of E2F, Rb, or p53 family of transcription factors through their transcriptional targets, which include many of the components described here. p53 regulates the stability of the checkpoint through levels of its mitosis target genes cdk1, cyclin B1, but also p21 (CDKN1A) and 14-3-3σ. The activity of Cdc25C is also regulated by Chk1 or Chk2-mediated phosphorylation, leading to its inactivation through binding to and sequestration by 14-3-3σ. ATM/ATR kinases transduce the DNA damage signal to the effector kinases Chk1 and Chk2. Chk1 and Plk1, by regulating Wee1, also play a role in the recovery from the arrest.

Following DNA damage, Chk1 and Chk2 are phosphorylated and thus activated by ATM and ATR,7,8 related members of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) family. In response to DNA damage, active Chk1 and Chk2 then phosphorylate the Cdc25C protein phosphatase at serine 216.9,10 Once phosphorylated, Cdc25C can then be bound by 14-3-3σ and sequestered in the cytoplasm.9 Cdc25C, only when it is in the nucleus, dephosphorylates the T14 and Y15 residues and thus activates the Cdk1/cyclin B1 complex.11-13 Additional phosphatases, Wip1 (PPM1D)14 and PP2A,15 may also regulate the checkpoint by dephosphorylating other factors that contribute to the activation of Cdk1. Cdk1/cyclin B can phosphorylate Cdc25C, further activating it and initiating a positive feedback loop.16 A nuclear export signal (NES) in Cyclin B1 facilitates rapid export of the Cdk1/cyclin B1 complex from the nucleus.17 Phosphorylation of the NES blocks the nuclear export by interfering with the binding of the nuclear export receptor CRM1.18

Sustaining A G2 Checkpoint: An Unexpected Role for P130

The strength of a G2 arrest elicited by a particular DNA damage signal depends on how long the arrest takes and how fast the recovery is. A role for the maintenance, but not the initiation of the G2 arrest has been earlier attributed to p53. By inactivating the p53 pathway, which occurs in the majority of tumor cells, the G1 arrest is abolished while the G2 arrest is only attenuated.19-22 Clearly, the G2-arrest occurs through checkpoint pathways implicating the DNA damage sensors ATM/ATR and effectors Chk1/Chk2 to converge on the regulation of the Cdc25C phosphatase and its downstream target, Cdk1.7 Surprisingly, a G2 arrest still occurs in ATM, ATR, Chk1, Chk2, and p53-deficient prostate cancer cells, suggesting that there are other pathways, at least in the context of prostate epithelial tumor cells, that contribute to an effective and stable G2 arrest (Ray, Shyam, Fraizer, Almasan, unpublished data).

Recent studies have specifically implicated p130, a retinoblastoma (Rb)-family pocket protein in the mechanism of G2 arrest following treatment with DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics.23,24 Rb family of proteins, comprised of Rb, p130, and p107, associate with a wide variety of transcription factors and chromatin remodeling enzymes forming transcriptional repressor complexes that control gene expression.25 Rb, a tumor suppressor critical for the control of cell cycle progression, regulates E2F activity. It has been known for some time that Rb-deficient cells have increased levels of mRNA and protein levels of genes that are under the transcriptional control of activating E2Fs.26,27 Recently, it has become clear that the inactivation of Rb-family members complexing with these activating E2Fs reduces the cellular ability to also undergo G2 arrest in response to DNA damage.23 A small molecule based on the Rb2/p130 spacer domain proved to be effective in inhibiting Cdk2 activity, cell cycle arrest, and tumor growth reduction in vivo.28

p53 can contribute to a sustained G2 arrest by inducing the transcription of p21 and 14-3-3σ.2 14-3-3σ sequesters Cdk1/cyclin B1 and Cdc25C in the cytoplasm,29,30 while p21 primarily inhibits the phosphorylation of p130 and p107 by Cdks, allowing them to repress the transcription of a large number of genes required for transit through G2.3,20 Similar to p53, p130 can repress transcription of cyclin B1 and cdk1 and therefore, enforce the G2 arrest. p130, just like p53 in certain cell type contexts, has additional targets that do not affect Cdk1 but also contribute to G2 arrest. For example, Plk1 is phosphorylated by Wee1 and may degrade it in a proteasome-mediated manner. Chk1 and Plk1 have been also suggested to be important for the checkpoint adaptation, a phenomenon that allows cells to escape from a G2 checkpoint into mitosis with damaged DNA.31 The cellular fate leading to survival or elimination by mitotic catastrophe during the next few cell divisions remains to be established. A surprising recent finding is that Artemis, previously known to be implicated in NHEJ DNA repair following its phosphorylation by DNA-PK can have an impact on the G2 recovery through direct interaction with cyclin B1. When it is phosphorylated by ATM, at lower doses of radiation, Artemis affects cyclin B1 complex formation with Cdk1 by sequestering it to the centrosome and by preventing Wee1-dependent phosphorylation.32

E2F Family Proteins: from DNA Damage to A Stable G2 Arrest

As the Rb family members interact with multiple binding partners and can control a wide range of signaling pathways,33 the role of individual E2Fs has been of great interest. The E2F family of transcription factors controls the expression of ten genes encoded by eight independent loci that are divided, based on sequence homology, into three groups.34 E2F1-3, which are highly regulated during cell growth and cell cycle generally, act as transcriptional activators. E2F4-5, which are constitutively expressed, are transcriptional repressors when bound to p130 or Rb. E2F6-8 act also as transcriptional repressors but do so independently of Rb.35 Various E2Fs have opposite biological effects but they can also complement each other.36 E2F4 and 5 are unique as they are regulated through their predominantly cytoplasmic cellular localization, which is facilitated by a NES.37 However, they do not have a nuclear localization signal (NLS); therefore it is believed that nuclear translocation is dependent on binding to p13038 or the other pocket proteins, Rb or p107.

Deregulation of the Rb/E2F pathway in human fibroblasts results following a genotoxic insult in E2F1-mediated apoptosis. This deregulation was first reported in Rb-deficient cells.26 E2F1-dependent apoptosis has now been shown to be dependent not only on p53, but also on ATM, NBS1, and Chk2. E2F1 expression results in MRN foci formation that are similar to irradiation-induced foci, as they colocalize with 53BP1 and γH2AX foci.39 These results suggest that E2F1-induced foci generate a cell cycle checkpoint that, with sustained E2F1 activity, eventually leads to apoptosis. E2F4 and E2F5, in complex with p130, are known to be present primarily in quiescent cells,40 with decreasing levels of E2F4 found associated with Rb and p107-Cdk2 during S-phase progression.41,42 Interestingly, we found that a typical genotoxic agent, ionizing radiation, induces complex formation of E2F4, but not E2F5, with the unphosphorylated form of p130.43 Examining the dynamics of its subcellular localization indicated that E2F4 and p130 were present in the nucleus a short time following irradiation; their colocalization reached a peak at 24 h. In contrast, the protein levels of E2F1, which may counterbalance the activity of E2F4,36 were dramatically downregulated. This pattern of decreased E2F1 levels was sustained following irradiation or treatment with the topoisomerase II inhibitor, VP16.

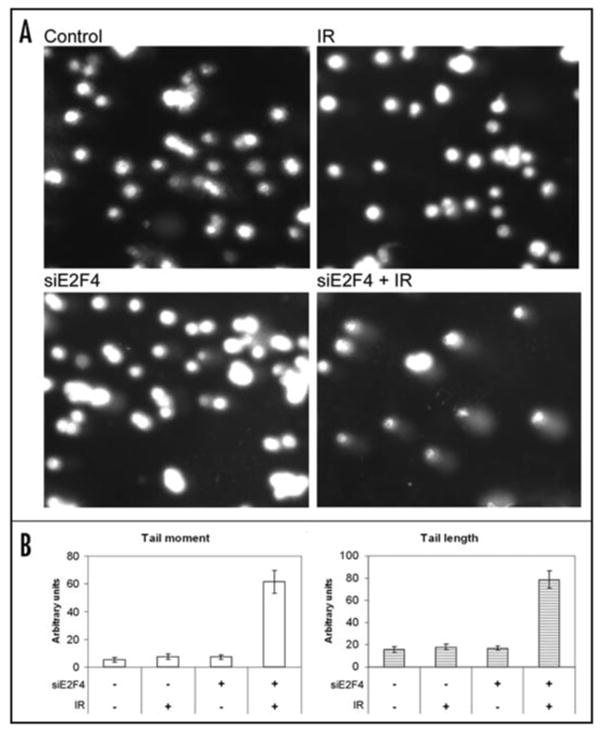

To examine the role of E2F4, we have chosen a transient, siRNA-mediated depletion of E2F4. This approach has been recently shown to be particularly fortuitous, as long-term, chronic loss of E2F activity, as produced in knockouts or stable knockdowns, does lead to compensation by other family members.34 In contrast, the analyses of acute loss of function reveal specific and distinct roles of these proteins. To assess the DNA damage and its repair, we used alkaline comet assays.44 This assay indicated that irradiation of C4-2 prostate carcinoma cells depleted of E2F4 by siRNA (siE2F4) markedly elevated DNA double strand break (DSB) levels as quantification of DNA damage showed more pronounced tail lengths as well as tail moments (Fig. 2A). Compared to radiation or siE2F4 treatments alone (Fig. 2B), these cells underwent apoptotic cell death that was characterized by both a sub-G1 and a sub-G2 DNA content. The appearance of sub-G2 DNA content is an interesting finding, as it can be easily confused with late S-phase cells by propidium iodide staining-based flow cytometry. When cells treated with siE2F4 were irradiated, the DNA content distributions demonstrated a large accumulation of cells with sub-G1 content, indicative of apoptotic cells and an accumulation of cells with an apparent late S phase DNA content. This finding is consistent with either a decrease in S phase transit in late S or apoptosis originating from cell with a 4C DNA content. BrdU incorporation in irradiated cells, used to distinguish S phase cells from those with the same DNA content that were not synthesizing DNA, decreased, consistent with cell cycle arrest in G1 and G2. A small sub-4C (sub-G2) population of BrdU-negative cells was markedly enhanced in E2F4 knockdown irradiated cells, suggesting that cell death from G2 arrest was elevated. Clonogenic cell survival studies provided an assessment of the long-term impact of the E2F4 knockdown. These cells became more sensitive to radiation, as indicated by a marked decrease in their LD50 values and clonogenic survival.3 A 4C DNA-content and low levels of cyclin A2 and B1 have been suggested also for cells encountering a G1 arrest, as these features are characteristic of endoreduplication.25 Alternatively, those cells that proceed through mitosis inappropriately, as a result, undergo mitotic catastrophe. However, the combined analyses of DNA content profiles, BrdU-incorporation, mitotic morphology, specific (cyclin A2 and B1), and general (MPM-2) mitotic markers excluded this possibility. Taken together, these data suggest that E2F4 activity helps to sustain G2 arrest and prevent cell death.

Figure 2.

E2F4 depletion leads to DNA strand breaks. (A) Comet assays were performed under alkaline conditions to determine the amount of double-strand DNA breaks. Cells treated with siRNA against E2F4 (100 nM, 24 h), or vehicle alone and ionizing radiation (IR) were trypsinized and washed in PBS before being added to preheated (37°C) low-melting point agarose. The solution was pipetted onto slides precoated with 1% agarose. The chilled slides were allowed to lyse for 40 min at 4°C in 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM NaEDTA (pH 10), 10 mM Tris Base, 1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100 prior to immersion in alkaline electrophoresis solution (300 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH 13). After 30 min, slides were placed into a horizontal electrophoresis chamber samples for ∼30 min (1 V/cm at 4°C). The slides were washed with deionized H2O to remove the alkaline buffer, dehydrated in 70% ice-cold EtOH and air-dried overnight. Slides were stained with PI (50 μg/ml) and examined by microscopy. B) Tail moment (TM) and tail length (TL) were used to quantify the DNA damage. Image analysis and quantification has been performed with NIH ImageJ. TM = % of DNA in the tail × TL; where % of DNA in the tail = tail area (TA) × tail average intensity (TAI) × 100/(TA × TAI) + [head area (HA) × head area intensity (HAI)].

In our study, cyclin B1, Bub1B, CENP-E, Chk1, HEC, Mad2L1, and PTTG1, all known to be regulated by E2F4 and to have a critical function in mitosis, were found to be associated with E2F4 function. Cdc6, known to be essential for DNA replication could also play an important role in mitosis.45 Moreover, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses demonstrated specific E2F4 recruitment to the promoter binding sites of PTTG1 and BUB3. In contrast, E2F4 was bound constitutively to Cdc6, an observation similar to the constitutive chromatin binding by p53 to its target promoters,46 indicating the involvement of other factors or post-transcriptional regulation for their activation. PTTG1, BUB1, BUB3, Mad2, and CENP-E are mitotic checkpoint proteins (Fig. 3). Stathmin,47 HEC, and Ect-2, are involved in spindle formation.48 The abundance of these targets and their individual role proposed in the DNA damage response is continuously expanding. For example, p130 regulates telomere length by interacting with RINT-1, previously identified as a Rad50-interacting protein. By forming a complex with Rad50 through RINT-1 p130 is likely to block the recombination dependent and telomerase-independent telomere lengthening in normal cells.49 Another example is DDB2, a gene mutated in XPE patients and involved in global genomic repair, especially the repair of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs). In Rb-null cells, where we have shown that E2F activity is elevated,50 global DNA repair is increased and removal of CPDs is more efficient than in wild-type cells. Endogenous E2F1 and E2F3 bind to the DDB2 promoter and treatment with E2F1-antisense or E2F1-siRNA decreases DDB2 transcription, demonstrating that E2F1 is a transcriptional regulator of DDB2.51

Figure 3.

Transcriptional programs implicating E2F and Rb family proteins in G2 control. E2F4 repressor activity is mainly regulated by p130, with Rb playing a role only when p130 and p107 are absent. The E2F4/p130 complex is translocated to the nuclei shortly after DNA damage where it binds to the promoters of and downregulates many transcriptional targets important for mitosis (cylin B1), mitotic checkpoints (Bub1, PTTG-1), or DNA damage checkpoints (Chk1). Repression of these targets assures maintenance of a stable G2 arrest for a tight control of mitotic entry. Activating E2Fs, such as E2F1, when released from Rb, following their activation through ATM and Chk2, lead to increased expression of genes important for DNA damage, DNA repair, but also apoptosis. Ultimately, a balance between the repressor and activating E2Fs may determine the physiological outcome.36 In bold are targets identified in our report.3

Several expression profiling experiments have documented that similar to p130, E2F4 regulates many genes that are critical for mitotic entry. Our results are consistent with previous studies based on combined cross-linking DNA immunoprecipitation and micro-array experiments,52 which have identified some of the same targets we have uncovered as E2F4 target genes with a putative role in various phases of the cell cycle including G2 and M.53 Similar targets were independently identified in studies examining specific p130 or Rb-regulated gene expression.24 At the same time, Rb-deficient U2OS cells showed an analogous dependence on E2F4-regulated genes,48 suggesting a context-dependence for p130 or Rb requirement for regulating mitotic entry. From our results and other studies we conclude that in response to DNA damage, these tumor cells undergo cell cycle exit initiated in G2.3,24,54 Independent profiling of the radiation response in human diploid fibroblasts has yielded similar results, with a prominent induction of additional markers of G0.55 Hypoxia also induces p130 dephosphorylation and nuclear accumulation, leading to the formation of E2F4/p130 complexes and increased occupancy of E2F4 and p130 at the RAD51 and BRCA1 promoters that suggest a coordinated transcriptional program responsible for an integral response to hypoxic stress to regulate DNA repair.56,57

Interestingly, a number of E2F4-bound genes originally identified through array analyses were also bound by E2F1,53 an observation extended to the promoters of genes regulated during G2 and M containing distinct E2F4 and E2F1 binding sites.52,58 Some of these promoters may display collaborative binding of several E2F family members to the same elements, such as in case of ect-2,48 while others distinct positive and negative E2F-dependent regulatory elements.58 In addition, E2F-dependent transcriptional activity may require binding of other transcription factors, such NF-Y or Myb to regulate the transcription of Cdk1.58 The balance between the E2Fs that occupy these promoters determines the physiological outcome, with more E2F4 bound resulting in cell cycle arrest.3,36

Conclusion

A working model, summarizing recent findings on the G2 initiation and maintenance discussed here, is presented in Figure 1. The salient feature is that while its initiation is dependent on cyclinB1/Cdk1 its stable maintenance is governed primarily by the activity of Rb and p53 family proteins. Together, these proteins may integrate the type and severity of the genotoxic stress with the proper G2 response to presumably assure that there is sufficient time for effective repair of the DNA damage. Earlier reports have indicated that Rb deficiency sensitizes cells to genotoxins by allowing S-phase entry under inappropriate conditions.26,50 This can be mimicked, for example by expressing typical Rb/E2F targets such as cyclin E1,59 which drives cells through S-phase. Our recent report3 suggests that, in a similar way, E2F4 deficiency allows inappropriate G2 progression that in response to DNA damage results in apoptosis without reaching mitosis. Interestingly, siRNA-mediated depletion of the classical radiation-induced checkpoint regulators ATM, ATR, Chk1, or Chk2 had no effect on the stability of the G2 checkpoint in these cells (Ray, Shyam, Fraizer and Almasan, unpublished data). ATR and Chk1 depletion impacts the G2 arrest only when p53 is rendered nonfunctional by expression of a dominant-negative mutant. In these cells, ATR seems to be hyperactivated, with a more limited role attributable to ATM.

Cellular radioresistance in tumor cells can be attributed to a strong G2 checkpoint activation that can be abolished by agents that inhibit the G2 checkpoint. Cell cycle G2 checkpoint abrogation is also an attractive strategy for sensitizing cancer cells to DNA-damaging anti-cancer agents without increasing adverse effects on normal cells.60 Interestingly, a recent report has suggested that G2 checkpoint inhibitors may be most effective at an earlier stage in the cell cycle,61 a stage that may correspond to what has been reported to be regulated by E2F4.3 Genome-wide analysis of E2F-dependent transcriptional regulation has identified many potential gene targets. Whether such individual targets play a major role in a specific cell type or biological context or that their cooperativity is needed to achieve tight control of the G2 to M-phase transition still needs to be established.

Acknowledgments

Work described in this article was supported by a research grant from the US National Institutes of Health (CA81504).

References

- 1.Iliakis G, Wang Y, Guan J, Wang H. DNA damage checkpoint control in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5834–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl GM, Carr AM. The evolution of diverse biological responses to DNA damage: Insights from yeast and p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E277–86. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-e277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby ME, Jacobberger J, Gupta D, Macklis RM, Almasan A. E2F4 regulates a stable G2 arrest response to genotoxic stress in prostate carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:1897–909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton FS, Parker LL, Geahlen RL, Piwnica WH. Mechanisms of p34cdc2 regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1675–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagting A, Karlsson C, Clute P, Jackman M, Pines J. MPF localization is controlled by nuclear export. Embo J. 1998;17:4127–38. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker LL, Piwnica-Worms H. Inactivation of the p34cdc2-cyclin B complex by the human WEE1 tyrosine kinase. Science. 1992;257:1955–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1384126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–23. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray S, Shyam S, Fraizer G, Almasan A. S-phase checkpoints regulate Apo2 Ligand/Tumor Necrosis Factor-related Apoptosis-inducing Ligand and CPT-11-induced apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1368–78. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blasina A, de Weyer IV, Laus MC, Luyten WH, Parker AE, McGowan CH. A human homologue of the checkpoint kinase Cds1 directly inhibits Cdc25 phosphatase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furnari B, Blasina A, Boddy MN, McGowan CH, Russell P. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:833–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon MJ, Glotzer M, Lee TH, Philippe M, Kirschner MW. Cyclin activation of p34cdc2. Cell. 1990;63:1013–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng CY, Graves PR, Thoma RS, Wu Z, Shaw AS, Piwnica-Worms H. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: Regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science. 1997;277:1501–5. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma RS, Richman R, Wu Z, Piwnica-Worms H, Elledge SJ. Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: Linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science. 1997;277:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shreeram S, Demidov ON, Hee WK, Yamaguchi H, Onishi N, Kek C, Timofeev ON, Dudgeon C, Fornace AJ, Anderson CW, Minami Y, Appella E, Bulavin DV. Wip1 phosphatase modulates ATM-dependent signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 2006;23:757–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolis SS, Perry JA, Forester CM, Nutt LK, Guo Y, Jardim MJ, Thomenius MJ, Freel CD, Darbandi R, Ahn JH, Arroyo JD, Wang XF, Shenolikar S, Nairn AC, Dunphy WG, Hahn WC, Virshup DM, Kornbluth S. Role for the PP2A/B56delta phosphatase in regulating 14-3-3 release from Cdc25 to control mitosis. Cell. 2006;127:759–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izumi T, Walker DH, Maller JL. Periodic changes in phosphorylation of the Xenopus cdc25 phosphatase regulate its activity. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:927–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.8.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pines J, Hunter T. The differential localization of human cyclins A and B is due to a cytoplasmic retention signal in cyclin B. Embo J. 1994;13:3772–81. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J, Bardes ES, Moore JD, Brennan J, Powers MA, Kornbluth S. Control of cyclin B1 localization through regulated binding of the nuclear export factor CRM1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2131–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown JP, Sedivy JM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor WR, Stark GR. Regulation of the G2/M transition by p53. Oncogene. 2001;20:1803–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan TA, Hwang PM, Hermeking H, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Cooperative effects of genes controlling the G2/M checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1584–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stark GR, Taylor WR. Control of the G2/M transition. Mol Biotechnol. 2006;32:227–48. doi: 10.1385/MB:32:3:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polager S, Ginsberg D. E2F mediates sustained G2 arrest and down-regulation of Stathmin and AIM-1 expression in response to genotoxic stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1443–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson MW, Agarwal MK, Yang J, Bruss P, Uchiumi T, Agarwal ML, Stark GR, Taylor WR. p130/p107/p105Rb-dependent transcriptional repression during DNA-damage-induced cell-cycle exit at G2. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1821–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macaluso M, Montanari M, Giordano A. Rb family proteins as modulators of gene expression and new aspects regarding the interaction with chromatin remodeling enzymes. Oncogene. 2006;25:5263–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almasan A, Yin Y, Kelly RE, Lee EY, Bradley A, Li WW, Bertino JR, Wahl GM. Deficiency of retinoblastoma protein leads to inappropriate S-phase entry, activation of E2F-responsive genes, and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5436–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrera RE, Chen F, Weinberg RA. Increased histone H1 phosphorylation and relaxed chromatin structure in Rb-deficient fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11510–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagella L, Sun A, Tonini T, Abbadessa G, Cottone G, Paggi MG, De Luca A, Claudio PP, Giordano A. A small molecule based on the pRb2/p130 spacer domain leads to inhibition of cdk2 activity, cell cycle arrest and tumor growth reduction in vivo. Oncogene. 2007;26:1829–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan TA, Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3σ is required to prevent mitotic catastrophe after DNA damage. Nature. 1999;401:616–20. doi: 10.1038/44188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, He TC, Zhang L, Thiagalingam S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3σ is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syljuasen RG, Jensen S, Bartek J, Lukas J. Adaptation to the ionizing radiation-induced G2 checkpoint occurs in human cells and depends on checkpoint kinase 1 and Polo-like kinase 1 kinases. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10253–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geng L, Zhang X, Zheng S, Legerski RJ. Artemis links ATM to G2/M checkpoint recovery via regulation of Cdk1-cyclin B. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2625–35. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02072-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khidr L, Chen PL. RB, the conductor that orchestrates life, death and differentiation. Oncogene. 2006;25:5210–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kong LJ, Chang JT, Bild AH, Nevins JR. Compensation and specificity of function within the E2F family. Oncogene. 2007;26:321–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Attwooll C, Denchi EL, Helin K. The E2F family: Specific functions and overlapping interests. Embo J. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosby ME, Almasan A. Opposing roles of E2Fs in cell proliferation and death. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1208–11. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaubatz S, Lees JA, Lindeman GJ, Livingston DM. E2F4 is exported from the nucleus in a CRM1-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1384–92. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1384-1392.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chestukhin A, Litovchick L, Rudich K, DeCaprio JA. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of p130/RBL2: Novel regulatory mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:453–68. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.453-468.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frame FM, Rogoff HA, Pickering MT, Cress WD, Kowalik TF. E2F1 induces MRN foci formation and a cell cycle checkpoint response in human fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2006;25:3258–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sardet C, Vidal M, Cobrinik D, Geng Y, Onufryk C, Chen A, Weinberg RA. E2F-4 and E2F-5, two members of the E2F family, are expressed in the early phases of the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2403–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi Y, Rayman JB, Dynlacht BD. Analysis of promoter binding by the E2F and pRB families in vivo: Distinct E2F proteins mediate activation and repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:804–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farkas T, Hansen K, Holm K, Lukas J, Bartek J. Distinct phosphorylation events regulate p130- and p107-mediated repression of E2F-4. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26741–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DuPree EL, Mazumder S, Almasan A. Genotoxic stress induces expression of E2F4, leading to its association with p130 in prostate carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4390–3. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olive PL. The comet assay: An overview of techniques. Methods Mol Biol. 2002;203:179–94. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-179-5:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boronat S, Campbell JL. Mitotic Cdc6 stabilizes anaphase-promoting complex substrates by a partially Cdc28-independent mechanism, and this stabilization is suppressed by deletion of Cdc55. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1158–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01745-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crosby ME, Oancea M, Almasan A. p53 binding to target sites is dynamically regulated before and after ionizing radiation-mediated DNA damage. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2004;23:67–79. doi: 10.1615/jenvpathtoxoncol.v23.i1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polager S, Kalma Y, Berkovich E, Ginsberg D. E2Fs up-regulate expression of genes involved in DNA replication, DNA repair and mitosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:437–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eguchi T, Takaki T, Itadani H, Kotani H. RB silencing compromises the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint and causes deregulated expression of the ECT2 oncogene. Oncogene. 2007;26:509–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong LJ, Meloni AR, Nevins JR. The Rb-related p130 protein controls telomere lengthening through an interaction with a Rad50-interacting protein, RINT-1. Mol Cell. 2006;22:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almasan A, Linke S, Paulson T, Huang LC, Wahl GM. Genetic instability as a consequence of inappropriate entry and progression through S-phase. Cancer Metast Rev. 1995;14:59–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00690212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prost S, Lu P, Caldwell H, Harrison D. E2F regulates DDB2: Consequences for DNA repair in Rb-deficient cells. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cam H, Dynlacht BD. Emerging roles for E2F: Beyond the G1/S transition and DNA replication. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:311–6. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ren B, Cam H, Takahashi Y, Volkert T, Terragni J, Young RA, Dynlacht BD. E2F integrates cell cycle progression with DNA repair, replication, and G2/M checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2002;16:245–56. doi: 10.1101/gad.949802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baus F, Gire V, Fisher D, Piette J, Dulic V. Permanent cell cycle exit in G2 phase after DNA damage in normal human fibroblasts. Embo J. 2003;22:3992–4002. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou T, Chou JW, Simpson DA, Zhou Y, Mullen TE, Medeiros M, Bushel PR, Paules RS, Yang X, Hurban P, Lobenhofer EK, Kaufmann WK. Profiles of global gene expression in ionizing-radiation-damaged human diploid fibroblasts reveal synchronization behind the G1 checkpoint in a G0-like state of quiescence. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:553–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bindra RS, Glazer PM. Repression of RAD51 gene expression by E2F4/p130 complexes in hypoxia. Oncogene. 2007;26:2048–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bindra RS, Gibson SL, Meng A, Westermark U, Jasin M, Pierce AJ, Bristow RG, Classon MK, Glazer PM. Hypoxia-induced down-regulation of BRCA1 expression by E2Fs. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11597–604. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu W, Giangrande PH, Nevins JR. E2Fs link the control of G1/S and G2/M transcription. Embo J. 2004;23:4615–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mazumder S, Gong B, Almasan A. Cyclin E induction by genotoxic stress leads to apoptosis of hematopoietic cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:2828–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sha SK, Sato T, Kobayashi H, Ishigaki M, Yamamoto S, Sato H, Takada A, Nakajyo S, Mochizuki Y, Friedman JM, Cheng FC, Okura T, Kimura R, Kufe DW, Vonhoff DD, Kawabe T. Cell cycle phenotype-based optimization of G2-abrogating peptides yields CBP501 with a unique mechanism of action at the G2 checkpoint. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:147–53. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sturgeon CM, Knight ZA, Shokat KM, Roberge M. Effect of combined DNA repair inhibition and G2 checkpoint inhibition on cell cycle progression after DNA damage. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:885–92. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]