Abstract

Background

Silencing of genes inserted near telomeres provides a model to investigate the function of heterochromatin. We initiated a study of telomeric silencing in Neurospora crassa, a fungus that sports DNA methylation, unlike most other organisms in which telomeric silencing has been characterized.

Results

The selectable marker, hph, was inserted at the subtelomere of Linkage Group VR in an nst-1 (neurospora sir two-1) mutant and was silenced when nst-1 function was restored. We show that NST-1 is an H4-specific histone deacetylase. A second marker, bar, tested at two other subtelomeres, was similarly sensitive to nst-1 function. Mutation of three additional SIR2 homologues, nst-2, nst-3 and nst-5, partially relieved silencing. Two genes showed stronger effects: dim-5, which encodes a histone H3 K9 methyltransferase and hpo, which encodes heterochromatin protein-1. Subtelomeres showed variable, but generally low, levels of DNA methylation. Elimination of DNA methylation caused partial derepression of one telomeric marker. Characterization of histone modifications at subtelomeric regions revealed H3 trimethyl-K9, H3 trimethyl-K27, and H4 trimethyl-K20 enrichment. These modifications were slightly reduced when telomeric silencing was compromised. In contrast, acetylation of histones H3 and H4 increased.

Conclusion

We demonstrate the presence of telomeric silencing in Neurospora and show a dependence on histone deacetylases and methylation of histone H3 lysine 9. Our studies also reveal silencing functions for DIM-5 and HP1 that appear independent of their role in de novo DNA methylation.

Background

Linear chromosomes pose a problem for replication of the terminal section of the DNA strand with a 5' end. The problem is solved in most eukaryotes by the addition of repeated sequences to the chromosome ends [1]. Thus the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae sports TG1–3 repeats on the ends of its chromosomes [2], while telomeres of both the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa and humans comprise TTAGGG repeats [3,4]. Drosophila's chromosome ends are capped by arrays of retrotransposons and the adjacent subtelomeric DNA consists of repetitive elements called telomere-associated sequences (TAS) [4]. TAS appear cytologically condensed (that is, heterochromatic) [5] and confer silencing on nearby genes, apparently because of spreading of silent heterochromatin. This phenomenon, called 'telomeric silencing', or 'telomere position effect' (TPE), was initially discovered and studied using transgenes but it also appears to regulate endogenous subtelomeric genes [6-8].

Telomeric silencing has been demonstrated in organisms ranging from yeasts to humans (reviewed in [9]) but it has been best characterized in S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Drosophila melanogaster, organisms that have no, or very little, DNA methylation. Heterochromatin at S. cerevisiae telomeres is nucleated by the telomere repeat binding protein Rap1 [10,11]. Telomeric silencing requires histone deacetylation by the conserved nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent histone deacetylase (HDAC) Sir2p [12], reviewed in [13]. Sir2p is found in a complex with Sir4p, which interacts with Sir3p [14]. While Sir2p homologues (sirtuins) have been found in all eukaryotes examined, Sir3p and Sir4p are restricted to close relatives of S. cerevisiae. The fission yeast S. pombe lacks Sir3p and Sir4p but employs methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (K9) plus a Sir2p homologue (Sir2) for silencing [15]. Deacetylation by Sir2 allows methylation of K9 by the Clr4 histone methyltransferase (HKMT), which in turn allows for binding by a homologue of Heterochromatin Protein-1 (HP1), Swi6 [15,16]. Swi6 is recruited to telomeres by interaction with the telomere repeat binding factor Taz1, which interacts with Rap1 and the RNAi-RITS complex [17].

The mechanism of telomeric silencing is largely unknown in plants and animals [1]. Silencing in Drosophila is dependent on telomere length, which depends on HP1 and its interaction with both telomere DNA and methylated H3 K9 [18-21]. One of the five Drosophila SIR2 homologues was tested for involvement in telomeric silencing but none was detected [22]. Sequences associated with mammalian telomeres show features of heterochromatin, including DNA methylation, trimethylated H4 K20, trimethylated H3 K9 and bound HP1, but the role of these factors remains to be elucidated [1]. Study of telomeric silencing in humans and mice has been limited, presumably in part because genes involved in heterochromatin formation and DNA methylation are essential in these organisms. We therefore initiated a study of telomeric silencing in N. crassa, which has DNA methylation like plants and mammals, but does not depend on it for survival.

A single DNA methyltransferase (DNMT), DIM-2, is responsible for all known DNA methylation in Neurospora [23]. DNA methylation is directed by Neurospora's single HP1 homologue to chromosomal regions in which histone H3 is trimethylated at K9 by the HKMT DIM-5 [24-26]. DNA methylation in Neurospora is found predominantly at transposon relics [27], many of which are scattered throughout the genome but are most concentrated in centromeric and telomeric regions [28-30].

To look for TPE in Neurospora, we inserted transgenes near telomeres in mutants that were defective in candidate silencing genes and were thus predicted to relieve the telomeric silencing. We initially tested several putative sirtuins, which we named nst-1 (Neurospora sir two) through nst-7 [31]. We found evidence of TPE in Neurospora and found that several but not all of the nst genes are involved in silencing. We also tested the involvement of DIM-5, HP1 and DIM-2 to assess the potential influence of DNA methylation on TPE. Finally, we tested the effect of chemical inhibitors of HDACs and DNA methylation. We found evidence for the involvement of DIM-5, HP1 and HDACs in telomeric silencing in Neurospora. Interestingly, we found that the telomeric transgenes and native subtelomeric sequences are lightly methylated and that mutation of dim-2 can affect TPE, although not at all telomeres. We conclude that silencing by DNA methylation at non-telomeric chromosomal sites and silencing at telomeres share some components (DIM-5 and HP1) but represent distinct silencing pathways.

Results

Inactivation of nst genes

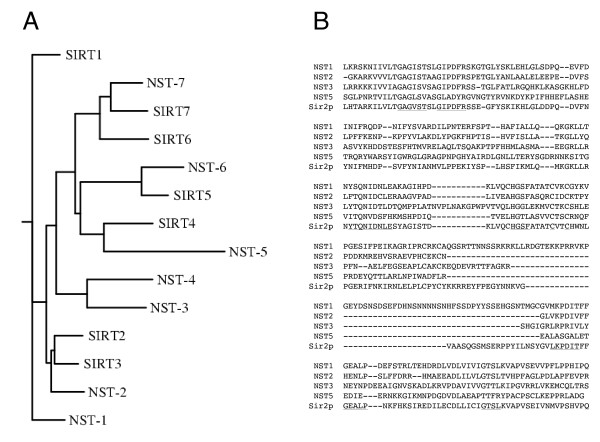

To investigate whether Neurospora shows telomeric silencing, we needed to insert a genetic marker in a subtelomeric region and then test its expression in various genetic backgrounds. As the histone H4 K16-specific deacetylase Sir2p is central to telomeric silencing in previously examined eukaryotes and has also been implicated in other forms of silencing [9], we chose to test Neurospora homologues of Sir2p first. The Neurospora genome contains seven genes predicted to encode a protein with the NAD+-dependent deacetylase domain typical of the Sir2 family, the same number found in the human genome [32]. We designated these genes nst-1 (Neurospora sir two) through nst-7 [31]. NST-1 is most closely related to S. pombe Sir2p and S. cerevisiae Sir2p and Hst1p, two proteins that have partially redundant functions in telomeric silencing [12,33,34]. Neurospora also has close homologues of S. cerevisiae Hst3p (NST-4) and Hst4p (NST-3), which both act on acetylated K56 of histone H3 [35] and are required for telomeric silencing in yeast [33]. NST-2 is most closely related to S. cerevisiae Hst2p, which is cytosolic and disrupts telomeric silencing when over-expressed [36]. A tree based on a single alignment of the putative Sir2 catalytic domains of the Neurospora and human sirtuins (Sir2 homologues) is shown in Figure 1A. While we cannot assume functional similarities based on this level of sequence similarity, it should be noted that the human sirtuins are not all nuclear histone deacetylases. One study showed localization of the human sirtuins in the nucleus (SIRT1), the cytosol (SIRT2), mitochondria (SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5), heterochromatin (SIRT6), and the nucleolus (SIRT7) [32] (Figure 1A). More recently it was shown that SIRT4 is a mitochondrial ADP-ribosyl transferase [37].

Figure 1.

A) Phylogenetic tree of Sir2 homologues from N. crassa (NST-1 through NST-7) and humans (SIRT1 through SIRT7) based on a single CLUSTALW alignment of their putative Sir2 catalytic domains. B) Alignment of the Sir2 domain from S. cerevisiae Sir2p with the corresponding regions of Neurospora sirtuins NST-1, NST-2, NST-3, and NST-5. The most highly conserved regions are underlined in the Sir2p sequence.

We used RIP (repeat-induced point mutation) [38] to generate strains with nonsense mutations in nst-1. One such strain (N1982) served as the initial host for insertion of a telomeric reporter gene (see below). We also employed RIP to generate likely null alleles of several other nst genes; altogether, we identified strains with one or more stop codons in, or upstream of, the putative deacetylase domains of nst-1, -2, -3 and -5 (Figure 1B). The nst-1RIP1sequence (EU869540) introduces a single stop codon at Q255, well within the conserved region of Sir2p, which extends from roughly L197 through Q473. The nst-2RIP1sequence (EU869542) has a mutation in the predicted start codon (ATG to ATA). The next potential start codon is M165, downstream of the region that is predicted to encode the deacetylase catalytic domain. The mutations in nst-3RIP1 (EU869541) generate a stop codon at Q69. The nst-5RIP1 sequence (EU872050) contains seven predicted nonsense mutations (at W115, R152, Q163, Q177, Q196, Q203, and R234). Interestingly, unlike the case in S. cerevisiae [33], none of these mutations resulted in any significant growth phenotype, even when nst-1, -3, and -5 were combined (data not shown).

Silencing of hph at Telomere VR

As a first step to test for telomeric silencing in Neurospora, we inserted a selectable marker, hph, into a subtelomeric region by homologous recombination in strain N1982, see figure 2, which carries the nst-1RIP1 mutation. The hph gene confers hygromycin resistance, even when hph is expressed at a low level. Our initial work relied on the two described Neurospora telomere sequences, IVL and VR [3,29]. From a screen of roughly 150 transformants by Southern hybridization, we identified a single clone with the correct integration near Tel VR; nearly all other transformants had ectopic insertions, as is typical in Neurospora. Several attempts to insert the selectable mtr allele into the subtelomeric region of telomere IVL failed to yield an isolate with a homologous integration.

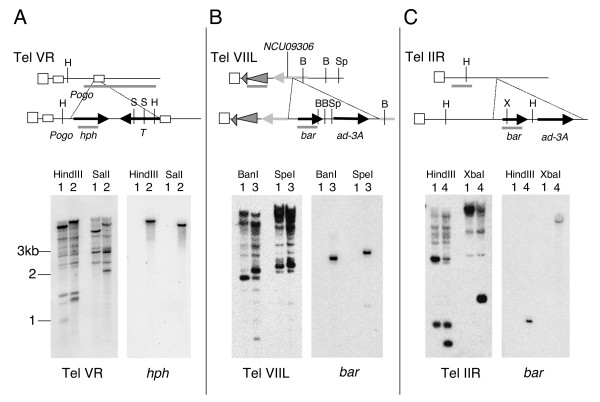

Figure 2.

Engineered subtelomeric markers. A-C) Top of each panel shows a cartoon map (not to scale) of inserted selectable markers at telomeres VR (contig 7.37, panel A), VIIL (contig 7.251, panel B) and IIR (contig 7.77, panel C). Vertical striped bars represent telomeric (TTAGGG)n repeats and diagonal striped bars in A represent Pogo LTRs [29]. Gray triangles on Tel VIIL (B) represent CenVII repeat element (194–280 bp from end) and a second unnamed repeat element (280–1077 bp from end). Southern blots of DNA from strains 1 (N150; WT), 2 (N3120; Tel VR::hph), 3 (N3440; TelVIIL::bar), 4 (N3456; TelIIR::bar) digested with the enzyme named at the top of each autoradiogram. Probes used are indicated under each panel and shown as gray bars in the maps.

We backcrossed the transformant with the desired insertion at Tel VR to an nst-1+ strain and found that hygromycin resistance (HygR) was lost in progeny with the nst-1+ allele, providing evidence for telomeric silencing in Neurospora and indicating that nst-1 plays a role in this process (Figure 3A and 3B). As a control, we inserted the hph construct at random ectopic chromosomal locations in a nst-1+ strain by co-transformation with pBARKS1[39], which confers resistance to Basta. Strains bearing hph sequences were identified by Southern hybridization and were all found to be HygR, confirming that hph is expressed when not at a telomeric locus (data not shown).

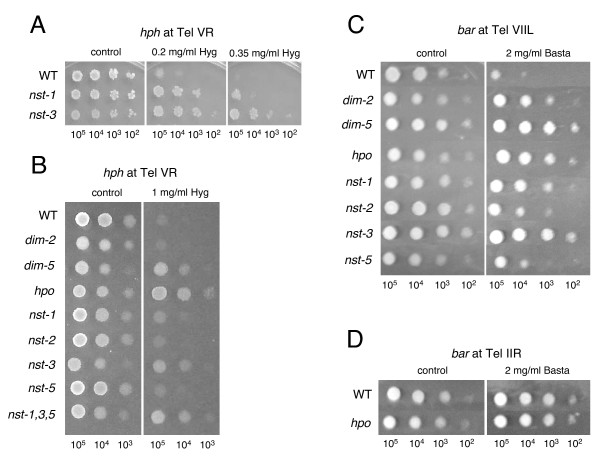

Figure 3.

Telomeric silencing depends on dim-5, hpo and nst genes. Conidia from strains carrying the telomere VR hph allele were spotted at densities noted at the bottom of each panel to test sensitivity to moderate (A) or high (B) levels of Hygromycin. Strains used in A were: N2285 (nst+, "WT"); N2130 (nst-1RIP1); N2635 (nst-3RIP1). Strains used in B were: N3120 (nst+, "WT"); N2833 (dim-2); N2997 (dim-5); N3004 (hpo); N3125 (nst-1RIP1); N2667 (nst-2RIP1); N3126 (nst-3RIP1); N3130 (nst-5RIP1); N3132 (nst-1, nst-3, nst-5). C) Conidia from strains N3441 (nst+), N3447 (dim-2), N3449 (dim-5), N3443 (hpo), N3452 (nst-1RIP1), N3453 (nst-2RIP1), N3455 (nst-3RIP1), and N3445 (nst-5RIP1) were spotted on plates with or without Basta to assay expression of the bar transgene targeted to telomere VIIL. D) Conidia from strains N3457 (nst+) and N3456 (hpo) were spotted on plates with or without Basta to assay expression of the bar transgene targeted to telomere IIR.

To determine if more than one nst gene is required for telomeric silencing, we combined nst mutations described above with this hph marker and then tested the effect of the mutations on expression of hph at Tel VR. No loss of silencing was detected in spot tests with the nst-2 mutant (Figure 3B) but mutation of nst-3 resulted in striking derepression of hph (Figure 3A and 3B). Mutation of nst-5 also relieved silencing (Figure 3B). While the nst-3 mutant showed robust growth on hygromycin, the nst-1 and nst-5 mutants showed barely visible growth when 10,000 or fewer conidia were spotted. However, resistance to hygromycin was reproducibly greater than in a nst+ strain, and growth was more robust at lower hygromycin concentrations (shown in Figure 3A for nst-1). As one approach to test the possibility that these genes are partially redundant, we constructed a strain defective for nst-1, -3 and -5 and compared its level of HygR with those of the single mutants. The triple mutant showed a similar level of resistance to nst-3 (Figure 3B).

We also generated strains to test the possible effect on telomeric silencing of genes required for DNA methylation, namely dim-2, dim-5 and hpo, which respectively encode the DNMT responsible for all known methylation in Neurospora [23], the HKMT responsible of methylation of K9 on histone H3, and the adaptor protein HP1. Elimination of DNA methylation by mutation of dim-2 had no discernable effect on expression of hph at Tel VR (Figure 3B). In contrast, both the HKMT DIM-5 and HP1, which reads the mark created by DIM-5, were critical for silencing of this marker (Figure 3B).

Silencing of bar at Telomere VIIL

To determine whether telomeric silencing occurs at other Neurospora telomeres and works on other genes, we inserted the selectable markers bar, encoding Basta resistance, and ad-3A proximal to two other telomeres, namely those of chromosome arms VIIL and IIR (Figure 2B and 2C, respectively). These novel telomere regions were identified by sequencing and mapping clones containing TTAGGG repeats (Wu C, Kim YS, Smith KM, Li W, Hood HM, Staben C, Selker EU, Sachs MS, Farman ML, unpublished). As the hpo mutation provided the strongest relief of silencing of hph at Tel VR, we used an hpo strain as the transformation host. To reduce ectopic integrations, the strain also included a mutation of mus-52, the gene that encodes the KU80 homolog required for non-homologous end-joining of DNA double strand breaks [40]. Transformation with the Tel VIIL targeting plasmid (pTTK19) yielded two BastaR transformants and Southern hybridizations revealed that both had integrated the construct correctly (Figure 2B). Similarly, we obtained one BastaR transformant with the Tel IIR-targeting plasmid pTTK22 and confirmed that this clone integrated the transgenes properly on LG IIR (Figure 2C). While use of mus-52 facilitated integration of markers into subtelomeric sites on VIIL and IIR, equivalent attempts to target to Tel IVL were unsuccessful.

The transformants with markers at VIIL and IIR were crossed to restore hpo function and test for silencing. We found that bar expression from the allele at Tel VIIL was lost in the hpo+ background (Figure 3C). This implies that the telomeric silencing observed with hph at Tel VR was not a peculiarity of one chromosome or one marker. The ad-3A gene was expressed, even in the original transformant (data not shown) and we did not explore the possibility that its level of expression pattern depended on hpo or other markers. The Ku proteins play a role in telomere function in other organisms [41] so we tested the effect of the mus-52 mutation on expression of the Tel VIIL-targeted bar marker. The mus-52 mutation did not cause a loss of silencing (data not shown), as is also the case in S. pombe [42]. Interestingly, the Tel IIR bar allele was not silenced when introduced into an hpo+ background (Figure 3D).

Having demonstrated telomeric silencing on two Neurospora chromosomes, we wished to test whether they showed a similar dependence on Sir2p homologues and other proteins implicated in heterochromatin formation. We therefore crossed strains bearing the marked Tel VIIL with strains bearing mutations in dim-2, dim-5, hpo, and the various nst genes that we found to be involved in telomeric silencing on chromosome V. Mutation of dim-5, hpo, nst-1, nst-2, nst-3 and nst-5 all caused loss of silencing of bar at Tel VIIL (Figure 3C), albeit to various extents. The results were generally consistent with the results obtained for these genes with hph at Tel VR but we were surprised to find an effect of the nst-2 mutation, as this gene had no noticeable effect on hph silencing at Tel VR. Another notable difference concerns the DNMT DIM-2. Unlike the situation for hph at Tel VR, the dim-2 mutation caused derepression of the bar marker at Tel VIIL (Figure 3C) suggesting differential involvement of DNA methylation at these telomeres.

Inhibitors of HDACs relieve telomeric silencing

The HDAC Class I (Rpd3-like) and II (Hda1-like) inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) [43] was previously shown to cause selective inhibition of DNA methylation in Neurospora [44]. To further explore the mechanism of telomeric silencing in Neurospora, we tested the effect of inhibitors of DNA methylation and HDACs on the expression of hph at Tel VR and bar at Tel VIIL. We first used a plating assay to test the effect of the Class III (sirtuin) HDAC inhibitor nicotinamide [45] on TPE and also on expression of an interstitial allele of hph allele that was silenced by DNA methylation spreading from flanking sequences that had been subjected to RIP [46]. Nicotinamide caused relief of hph at Tel VR but not at the interstitial site (Figure 4A). This finding supports the genetic evidence that sirtuins are involved in telomeric silencing in Neurospora and implicates their HDAC activities. It also suggests that sirtuins are not required for maintenance of DNA methylation.

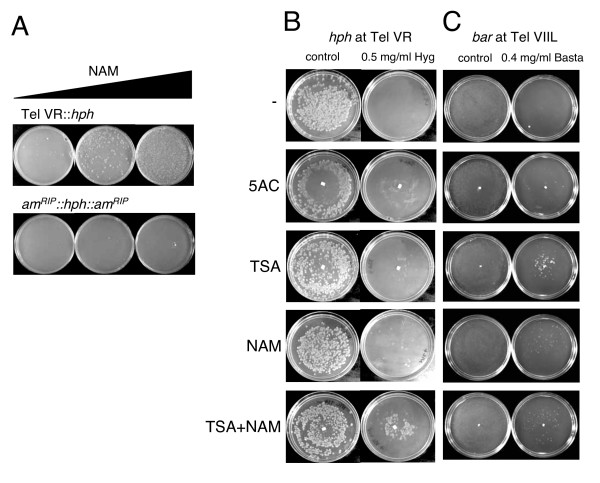

Figure 4.

Derepression of the subtelomeric transgenes by inhibitors of histone acetyltransferases and DNA methyltransferases. A) Nicotinamide (NAM) relieved silencing of telomeric hph (N2285) but not hph flanked by amRIP (N2015) at a non-telomeric site. All plates contained 0.6 mg/ml Hygromycin. Plates with NAM contained 0.1 mg/ml (middle plate) or 1 mg/ml (right plate) of the drug. Each plate received approximately 100,000 conidia. B) Approximately 1000 conidia from an nst+ strain (N3120) carrying the telVR hph allele were plated in the presence or absence of 0.5 mg/ml Hygromycin to assay the effect of the drugs 5-azacytidine (5AC), Trichostatin A (TSA) and NAM on telomeric silencing. C) Same as B except strain N3441 carrying the tel VIIL bar allele was plated in the presence and absence of 4 mg/ml Basta. Control plates lacking Basta show a lawn of growth.

We adopted an assay involving a gradient of inhibitors for additional tests of the effects of nicotinamide, TSA and the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-azacytidine (5AC) on expression of the telomeric hph (Figure 4B) and bar (Figure 4C) alleles. Both nicotinamide and TSA allowed a small fraction of conidia to escape silencing and grow on hygromycin, suggesting that both NAD+-dependent and -independent HDACs play a role in telomeric silencing. Interestingly, repeated tests showed that when both drugs were added together, the loss of silencing was significantly greater for telomeric hph, implying overlapping functions of members from different HDAC classes. In contrast to transcriptional silencing caused by DNA methylation, silencing of hph at Tel VR was unaffected by the DNA methylation inhibitor 5AC. This is consistent with our findings with strains defective in DNA methylation due to mutations in the dim-2 gene (Figure 3B). A small number of colonies escaped silencing of bar on Tel VIIL in the presence of 5AC (Figure 4C), consistent with relief of bar silencing in a dim-2 mutant (Figure 3C). In summary, these data suggest that multiple HDACs are involved in telomeric silencing and that DNA methylation is not universally required for gene silencing in Neurospora.

NST activity

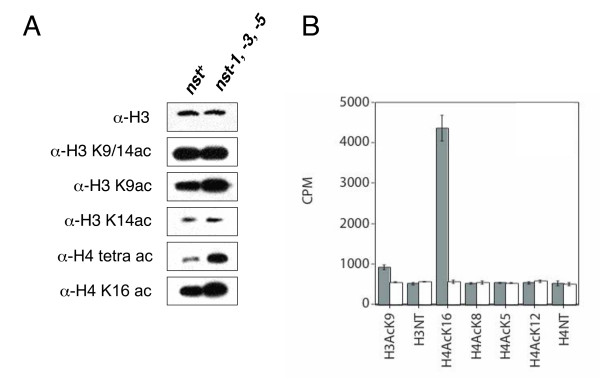

The nst genes were identified by homology to SIR2. Not all Sir2p homologues appear to be HDACs; some have been shown to have non-histone substrates or lack deacetylase activity toward all substrates tested (reviewed in [13]). In one approach to determine whether the NST proteins have HDAC activity, we used western blotting to assess whether mutation of nst genes affected the global level of histone acetylation at candidate residues. Initial tests revealed no change in the nst-1, -3 or -5 mutants (data not shown), consistent with the possibility that they are partially redundant. We therefore tested a triple (nst-1 nst-3 nst-5) mutant and, indeed, found significant hyperacetylation (Figure 5A) in contrast to the case with the single nst mutants. Although no change was detected with antibodies that recognize acetylated H3 K14 or acetylated H3 K9 and/or K14, an antibody against acetylated H3 K9 revealed increased acetylation in the triple nst mutant (Figure 5A). We also detected clearly increased acetylation of H4 in the nst triple mutant, both with H4 tetra-acetyl antibodies (recognizing acetyl K5, 8, 12, or 16) and with H4 K16-acetyl antibodies. These results are consistent with the idea that NST proteins are indeed HDACs.

Figure 5.

Histone H4 acetylation is increased in nst mutants. A) Western blots of nuclear extracts from strains N3120 (nst+) and N3132 (nst-1RIP1nst-3RIP1nst-5RIP1) probed for the indicated epitopes. Different exposure times were used (not indicated) to avoid saturation of signal. B)In vitro NAD+-dependent deacetylase assays with the indicated H3 or H4 peptide substrates (NT, unmodified N-terminal peptide). Grey bars show activity for purified NST-1 protein; white bars represent GST (only) control.

To directly test whether at least one of the predicted NST proteins is an HDAC, we expressed NST-1 in Escherichia coli and assayed it for NAD+-dependent deacetylase activity with various acetylated histone peptides. NST-1 displayed robust activity with an H4 peptide acetylated on K16 and weak activity with an H3 peptide acetylated on K9, but showed no activity on H4 peptides acetylated on K5, K8, or K12 (Figure 5B). Thus, the in vitro assays support the in vivo findings (Figure 5A and Figure 6, below) and indicate that at least one NST protein is a bona fide NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase.

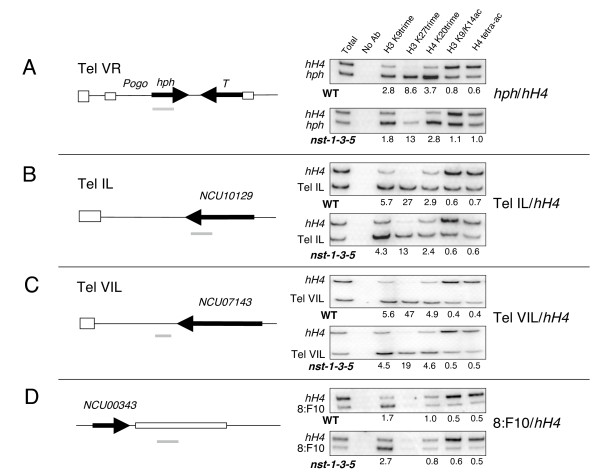

Figure 6.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to compare histone modifications near telomeres in WT and nst triple mutant strains. Telomeric regions investigated are shown in the schematics at left. Vertical striped bars represent telomeric (TTAGGG)n repeats and horizontal striped bars in A represent Pogo LTRs. Black bars represent open reading frames and are labeled according to the Broad Institute database. Strains N3120 (nst-1+) and N3132 (nst-1RIP1nst-3RIP1nst-5RIP1) show increased acetylation of H3 and H4 and decreased histone methylation at the derepressed hph gene at telomere VR. A-D) Immunoprecipitated chromatin was amplified with primers for the indicated regions, shown as gray bars. Values in the figure indicate enrichment of specific modifications at telomeric regions relative to euchromatic (hH4) regions (A-C). To determine these values bands were quantified using ImageQuant software and ratios were calculated relative to input DNA. D) We also tested a non-telomeric heterochromatic region with methylated DNA (8:F10) [27].

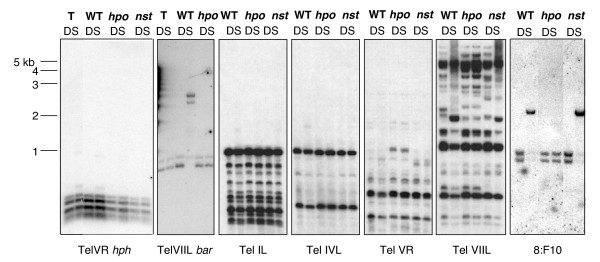

DNA methylation of subtelomeric regions

Most available information on the structure and sequence of telomeres and subtelomeric heterochromatic regions is from organisms that do not have DNA methylation. Thus we were interested to examine both native and introduced sequences associated with telomeres for methylation in Neurospora. We found evidence of light DNA methylation at the silenced Tel VR hph marker and robust DNA methylation at the Tel VIIL bar marker (Figure 7). This is consistent with our observation that dim-2 caused derepression of the bar marker at VIIL but did not affect hph expression at VR (Figure 3B and 3C). We also detected limited methylation at some, but not all, unmarked telomeres. Specifically, DpnII/Sau3AI sites were lightly methylated or unmethylated at telomeres IL, IVL, and VR but substantially methylated at Tel VIIL (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analyses of DNA methylation near telomeres. DNA was digested with isoschizomers DpnII (D) and Sau3AI (S), separated on agarose gels, blotted, and probed with telomere proximal regions to assay DNA methylation in these regions. Strains for the TelVR hph panel: N2292, the primary transformant with hph targeted to tel VR (T); N3120, a nst+ strain (WT); N3004, an hpo strain (hpo); N3132, the triple nst-1, -3, -5 mutant (nst). The hph probe was the first 600 bp of the coding region. Strains for the tel VIIL bar panel: N3440, the primary transformant with bar targeted to tel VIIL (T); N3441 (nst+); N3443 (hpo). The bar probe was the entire coding region. For the other panels, DNA samples of a wildtype strain, N150 (WT), an hpo mutant, N3004 (hpo), and N3132, a triple nst-1 nst-3 nst-5 mutant (nst) were processed as for the other panels and probed for: telomere IL (Tel IL; 226–1249 bp from end); telomere IVL (TelIVL; 2500–3657 bp from end); telomere VR (Tel VR; 1130–2887 bp from end); telomere VIIL (Tel VIIL; 324–1306 bp from end); a methylated repeat called 8:F10 (see text).

To examine whether the telomeric methylation is dependent on HP1, as found for DNA methylation at other described chromosomal sites [26], we tested the effect of a null mutation of hpo. In addition, we tested the effect of mutating the three nst genes that we had found resulted in hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 (Figure 5). Introduction of the hpo mutation introduced a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (Tel VR) but it clearly also resulted in loss of methylation at all regions tested, consistent with previous indications that hpo causes a global loss of methylation [26]. In contrast, DNA methylation of subtelomeric regions was essentially unaffected in the triple nst mutant. We also tested the effect of the nst mutation on methylation of a non-telomeric repeated element (8:F10) [27] and found no effect on DNA methylation in this region (Figure 7).

Histone modifications associated with silent telomeric regions

Little information is available about histone modifications in telomeric regions and no such information was available for Neurospora. We therefore used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to characterize key modifications of histones H3 and H4 associated with sequences near Neurospora telomeres. Both marked and unmarked telomeres were examined because of the possibility that introduced markers could influence the epigenetic state of the chromatin. Results from our genetic studies with dim-5, hpo and nst mutants and from western blots suggested that the TAS would at least sport methylated K9 on H3 and would perhaps also show hypoacetylated histones. We found reproducible differences between telomeric regions and interstitial euchromatic regions (for example, histone H4 gene, hH4) and, interestingly, we also found differences between the telomeric regions and interstitial heterochromatic regions, that is, regions that had undergone RIP and whose DNA is methylated (8:F10). Like previously tested products of RIP bearing DNA methylation, the marked (hph; Figure 6A) and unmarked (Tel IL & Tel VIL; Figure 6B and 6C, respectively) telomere-associated regions showed hypermethylation of H3 K9. Unlike interstitial heterochromatic sequences (Figure 6D and Honda S, Lewis Z, Selker EU, unpublished), however, the telomere-associated regions showed a striking enrichment for trimethylated H3 K27 and trimethylated H4 K20. In addition, both the marked and unmarked telomeric sequences showed hypoacetylation relative to the control euchromatic sequence (hH4).

The triple nst mutant attenuated the hypermethylation of H4 K20 and hypoacetylation of H3 and H4 at the marked telomere (note the ratio of telomeric to euchromatic PCR product normalized to the input DNA sample in Figure 6A). Whereas in the wild type the anti-histone H3 K9/K14 antibody produced a relative enrichment (hph/hH4) of 0.8 and the anti-tetracetylated histone H4 antibody produced a relative enrichment of 0.6 (Figure 6A), both H3 (K9/14) and H4 acetylation levels were equivalent for hph and hH4 in the nst triple mutant; thus, loss of silencing in the triple nst mutant correlated with a level of histone acetylation at telomeric hph typical of euchromatin. These results are consistent with the western blot results showing increased acetylation on both H3 and H4 in the nst triple mutant (Figure 5A). Equivalent results were found for the 5' end of the hph gene (shown in Figure 6A) and the middle of the coding region (data not shown). Although the calculated enrichment of hph/hH4 for H3 K27 trimethylation went up from 8.8 in wild type to 13.3 in the mutant, the intensity of the PCR product is greatly reduced in the mutant, which suggests that H3 K27 trimethylation of hph is also reduced in the triple nst mutant. Although H3 trimethyl-K9, H3 trimethyl-K27, and H4 trimethyl-K20 were enriched at the unmarked subtelomeric sequences, as for the telomeric hph, these modifications appeared mostly unchanged in the triple nst mutant. Only H3 trimethyl-K27 showed a reproducible change; it decreased about two-fold in the mutant (Figure 6B and 6C). The nst mutations did not effect DNA methylation at non-telomeric heterochromatic sequences (Figure 7, 8:F10) and also did not appear to greatly affect histone modifications at the region examined (8:F10; Figure 6D).

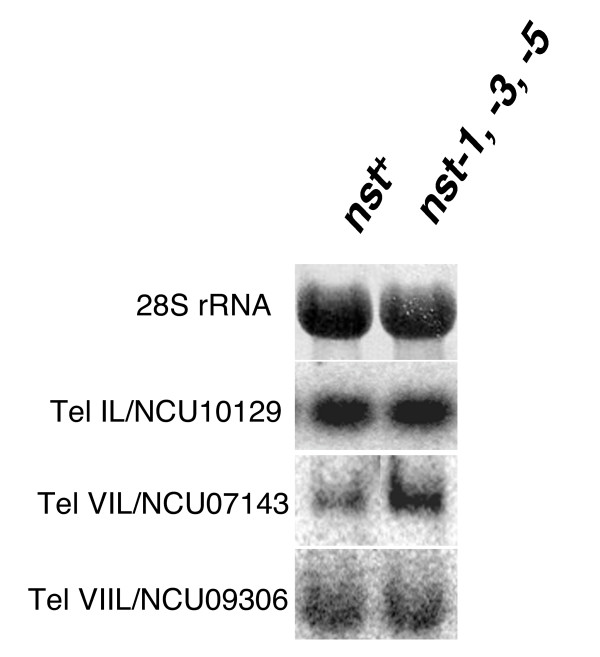

We also examined native Tel VIIL at the site where the bar gene was silenced and found comparable patterns of increased/decreased histone modifications, relative to control euchromatic sequences (data not shown). Interestingly, we also found hypoacetylation of H3 and H4 at all subtelomeric regions examined, including actively transcribed genes. The Tel IL and VIL primers amplify genes NCU10129.3 and NCU07143.3, respectively, both of which we found to be active genes. Northern analysis with RNA isolated from wild type and the triple nst strains showed that the expression of these genes, like their histone acetylation status, was comparable in the wild type and the triple nst mutant (Figure 8) [47,48]. In summary, changes in histone modifications in the nst triple mutant are localized to the Tel VR-targeted hph allele, with the exception of a general effect of reduction of H3 trimethyl-K27.

Figure 8.

Expression of genes near telomeres is unaffected by nst mutations. Total RNA was extracted [47] from N3120 (nst+) and N3132 (nst-1RIP1nst-3RIP1nst-5RIP1) and 20 μg was separated by agarose gel, blotted, and probed as described [48]. The 28S rRNA panel shows equivalent loading in both lanes by methylene blue staining of a blot. Other panels are autoradiograms after probing with the coding region of the gene closest to telomere IL (NCU010129.3), VIL (NCU07143.3), or VIIL (NCU09306.3).

Discussion

Structural similarities and differences between telomeres of Neurospora and other model organisms

The structure of the currently known Neurospora telomere sequences [49] is quite simple. The length of Neurospora (TTAGGG)n repeats (~200 bp) is roughly ten-fold less than in mammals [29]. Unlike other fungi and mammals (reviewed in [50]), subtelomeric regions in Neurospora do not consist of tandem repeats and do not contain a particular class of repeat element present at each telomere, or even at a subset of the characterized telomeres. Rather, a short stretch of AT-rich DNA (roughly 2 kb long but variable in length) separates the first telomere repeat unit from the most telomere-proximal gene (Wu C, Kim YS, Smith KM, Li W, Hood HM, Staben C, Selker EU, Sachs MS, Farman ML, unpublished). The evolutionary origin of this telomere arrangement likely reflects the action of a genome defense system called RIP in Neurospora [38]. The RIP machinery detects duplicated sequences and changes C:G to T:A base pairs, presumably by deamination of cytosines or methylcytosines [51]. The resulting AT-rich sequences serve as targets for the DNA methyltransferase DIM-2 [23], which typically methylates remaining cytosines [52-54]. Subtelomeric sequences of Neurospora show hallmarks of RIP, namely a deficiency of CpA dinucleotides and a corresponding overabundance of TpA dinucleotides, the RIP machinery's preferred substrate and product, respectively [52], and DNA methylation (Tel VIIL; Figure 7). The current subtelomeric sequences may have once shared homology that is now unrecognizable because of RIP and evolutionary divergence.

Telomeric markers for Neurospora

The simple structure of Neurospora subtelomeres facilitated our strategy to insert selectable markers near Neurospora telomeres. For Tel VR, we chose to insert a copy of hph within a Pogo transposon relic found directly adjacent to the telomere repeat (Figure 2A). We also inserted the T gene (encoding tyrosinase) at Tel VR, and expression of this allele of T correlated with expression of hph in nst-1 and nst-3 strains (data not shown). We did not analyze expression of this allele further as RIP may have been induced by the native copy of T in the Neurospora genome during successive crosses. For Tel VIIL, the bar and ad-3A markers were inserted within the coding region of an expressed gene, NCU09306.3, which is directly flanked by an unnamed RIP-mutated repeated element found at more than ten other chromosomal positions (none of which is within 100 kb of a known telomere) and a CenVII-like RIP-mutated region, which directly flanks the (TTAGGG)n telomere repeats (Figure 2). Thus, it is likely that NCU09306.3 is embedded in heterochromatin even though it is expressed, as is also the case for NCU10129.3, at Tel IL (Figure 6B and 8). ChIP data supported this possibility, showing an enrichment of histone methylation and absence of histone acetylation at the 3'end of NCU09306.3 (data not shown). Most importantly, our genetic data show that a marker inserted in NCU09306.3, like one inserted into a non-genic region near another telomere, is subject to telomeric silencing involving both histone deacetylation and histone methylation.

Involvement of histone deacetylases in telomeric silencing

The first evidence for telomeric silencing in Neurospora came from our observation of increased expression of the hph gene in a strain in which we had mutated nst-1, the closest homologue of S. cerevisiae SIR2. We then found evidence of extensive involvement of other deacetylases. The role of protein deacetylases, such as HDACs, is complex because of their multiple and partially overlapping functions. In S. pombe, telomeric silencing is dependent on deacetylation of histone H3 K9 and H4 K16 by Sir2, and subsequent methylation of histone H3 K9 [15,16]. A Sir2 deletion strain showed increased H3 K9 and H3 K14 acetylation at a subtelomeric region, and reduced H3 K9 methylation and Swi6/HP1 binding. Mutation of the Class I and II HDACs (Clr6 and Clr3, respectively) or treatment with the Class I/II HDAC inhibitor TSA also caused increased expression of telomere-linked genes [55,56]. In human cells, TSA, but not the sirtuin inhibitor sirtinol, caused derepression of a subtelomeric reporter and mislocalization of HP1 [57]. A recent study, however, showed SIRT6 is an H3 K9 deactylase that localizes to telomeres and is required for telomere integrity [58]. Little or no effect on subtelomeric gene expression was observed in mouse embryonic stem cells treated with TSA [59]. As such negative results of drug treatment assays are difficult to interpret, it remains possible that both Class I/II and III HDACs are required for mammalian telomere silencing; additional genetic studies may shed light on this.

Our finding that NST-1 is a NAD-dependent (Class III) HDAC, as expected, fits our observation that nicotinamide is a potent inhibitor of telomeric silencing in Neurospora (Figure 4). The finding that TSA also interfered with silencing strongly suggests that Class I or Class II HDACs are also important. Thus, it should be interesting to further explore the importance of both NAD-dependent and -independent HDACs in telomeric silencing. Increased acetylation at H3 K9 would of course be expected to interfere with methylation of this residue, but various HDACs may also be involved in silencing at other levels. For instance, N. crassa NST-1, S. pombe Sir2, S. cerevisiae Sir2p, and human HST-1 all appear to target H4 K16 for deacetylation. In the absence of these proteins, increased H4 K16 acetylation may somehow interfere with silencing. Our observation that loss of telomeric silencing was enhanced when nicotinamide and TSA were added in combination suggests overlapping roles of HDACs of Class I/II and Class III. It should be interesting to test mutants in the four Neurospora Class I and II HDACs (hda-1 through hda-4) [31] for their involvement in telomere silencing.

The finding that a triple nst mutant showed a greater increase in histone acetylation, as assayed by western blot of nuclear proteins and ChIP (Figures 5A and 7 and data not shown), than the individual nst-1, -3, or -5 mutants suggests that two or more of the nst genes have partially overlapping functions. The nst-2 mutant had no discernable effect on silencing of the hph at Tel VR, but reduced silencing of bar at Tel VIIL. Curiously, its closest homologues studied, S. cerevisiae Hst2 [36] and human SIRT2 [32], are cytosolic. Altogether, available information from Neurospora and other organisms is most consistent with all three classes of HDACs playing a role in telomeric silencing. It is also important to note that while individual mutants of nst-1, nst-3, or nst-5 caused a partial loss of telomeric silencing, there was no increase in histone acetylation assayed by western blot or ChIP in these mutants. It is possible that one or more of these genes encodes a protein that causes an indirect effect on telomere silencing.

Trimethyl-K9 in histone H3 and HP1 are required for telomeric silencing in Neurospora

We found that methylation of histone H3 K9, a mark produced by DIM-5 and required for DNA methylation [24,25], is required for telomere silencing (Figure 3B and 3C) and enriched at all telomeres tested (Figure 6). Similarly, HP1, which binds methylated H3 K9 and is thought to be essential for heterochromatin formation [26], is required for telomere silencing (Figure 3B and 3C). ChIP experiments showed that the silent hph transgene is marked with H3 K9 trimethylation as well as trimethyl H3 K27 and H4 K20 (Figure 6). This is the first report of a role for H3 K27 methylation in Neurospora, and an important observation that shows Neurospora telomeres better model mammalian telomeres than those of the yeasts, which completely lack H3 K27 methylation (and DNA methylation). All three histone methylation marks were modestly reduced in an nst-1, -3, -5 triple mutant, with the most striking reduction in H3 K27 methylation. Once the histone methyltransferases (HKMTs) responsible for methylation of H3 K27 and H4 K20 methylation are identified, it will be interesting to test whether these marks, like H3 K9 methylation, are required for telomeric silencing. H3 K27 methylation was not observed in other regions of heterochromatin (for example, 8:F10) so we hypothesize it is involved in telomere silencing but not DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is not generally required for silencing at Neurospora telomeres

Mutation of the dim-2 gene, which is responsible for all known DNA methylation in Neurospora [23], did not cause loss of silencing of the hph gene targeted to Tel VR (Figure 3B). Similarly, treatment with the DNA methylation inhibitor 5AC did not relieve silencing (Figure 4B). We conclude that the light DNA methylation observed at telomere VR (Figure 7) is not required for silencing in this region. This is consistent with the observation that 5AC had no effect on silencing of a telomeric transgene in human cancer cell lines [57]. Interestingly, telomeric transgenes in mouse embryonic stem cell lines become increasingly silenced and methylated as they are passaged and the eventual tight silencing and DNA methylation are reversible by 5AC [59].

In contrast to the situation at Tel VR, the sequences immediately proximal to Tel VIIL were significantly methylated (Figure 7) and DNA methylation was responsible for some silencing of bar inserted in this region. Mutation of dim-2 or treatment with 5AC both relieved silencing (Figures 3 and 4). It is interesting that dim-5 and hpo are required for telomeric silencing in Neurospora but DNA methylation, although frequently present, is not universally required to maintain silencing. Our findings provide the first examples of H3 K9 methylation acting to silence a gene independently of DNA methylation in Neurospora. It is noteworthy that mammals also use common factors for DNA methylation and telomere silencing [1] and telomere length is regulated by H3 K9 specific HKMTs in mouse [60]. Shortening of telomeres associated with aging is associated with changes in chromatin structure that alter the expression of neighboring genes [61].

In summary, our study on the structure and expression of sequences at Neurospora telomeres demonstrates the existence of telomeric silencing in Neurospora. We show important similarities, but also differences, in the silencing of markers integrated at subtelomeric regions. We also showed that at least one member of the Neurospora sirtuin family of NAD-dependent HDACs, NST-1, is a bona fide H4 K16 HDAC. Importantly, our work reveals an additional role for H3 K9 methylation and HP1 in Neurospora, independent of DNA methylation. It also provides evidence for the involvement of multiple classes of HDACs, including members of the NAD-dependent and -independent classes, and H3 K27 and H4 K20 HMTs. One major question remaining is how exactly heterochromatin is nucleated at Neurospora subtelomeres, as the Neurospora genome contains no good homologues of S. pombe Taz1 or mammalian telomere repeat binding factors.

Methods

Neurospora strains and growth conditions

A list of N. crassa strains used in this study is provided in Table 1[62,63]. Standard conditions were used for their growth and maintenance [64].

Table 1.

List of strains

| Strain Number | genotype | reference |

| N150 | mat A | FGSC2489 |

| N534 | mat a; mtrSR62col-4; trp-2 | [62] |

| N564 | mat A; Δmtr::hph | this study |

| N565 | mat A; mtrSR62col-4; trp-2 | this study |

| N593 | mat a; arg-12 | this study |

| N1275 | mat a; dim-2 arg-10 | [23] |

| N1445 | mat a his-3; am132inl | this study |

| N1447 | mat a his-3; inl | this study |

| N1674 | mat A his-3; lys-1 am132inl; amRIP::hph::amRIP | [63] |

| N1877 | mat his-3; Δdim-2::hph | [23] |

| N1982 | mat A; mtr col-4; nst-1RIP1trp-2 | this study |

| N2015 | his-3 cyh-1; am132inl; amRIP::hph::amRIP | this study |

| N2130 | mat a; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1trp-2 | this study |

| N2140 | mat A; dim-5 leu-2 pan-1 | [25] |

| N2225 | nst-1RIP1; am::hph::am | this study |

| N2264 | mat a his-3; dim-5 leu-2 pan-1 | [25] |

| N2284 | mat A; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1trp-2 | this study |

| N2285 | mat A; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; trp-2 | this study |

| N2288 | mat a; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1trp-2 | this study |

| N2292* | mat A; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1trp-2 | this study |

| N2552 | mat A his-3+::hpoRIP::gfp; hpoRIP2 | [26] |

| N2633 | mat a nst-2RIP1; inl | this study |

| N2634 | mat A nst-3RIP1; am132inl; amRIP::hph::amRIP | this study |

| N2635 | mat A nst-3RIP1 his-3+::nst-3RIP;mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; trp-2 | this study |

| N2636 | mat A nst-3RIP1; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1trp-2 | this study |

| N2664 | mat a; mtr col-4; telVR::hph::T | this study |

| N2667 | mat a nst-2RIP1; telVR::hph::T | this study |

| N2681 | mat A his-3+::nst-5RIP2; nst-5RIP1; amRIP::hph::amRIP | this study |

| N2693 | mat a; nst-5RIP1; telVR::hph::T | this study |

| N2833 | mat A; telVR::hph::T; dim-2 arg-10 | this study |

| N2921 | mat a nst-3RIP1; mtr col-4; lys-1 inl; trp-2; amRIP::hph::amRIP | this study |

| N2997 | mat A; dim-5 leu-2 pan-1; telVR::hph::T | this study |

| N3004 | mat A; telVR::hph::T; hpoRIP2 | this study |

| N3017 | mat A Δad-3A; Δmus-52::hph; hpoRIP2trp-2 | this study |

| N3120 | mat a; telVR::hph::T | this study |

| N3125 | mat a; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1 | this study |

| N3126 | mat A nst-3RIP1; telVR::hph::T; trp-2 | this study |

| N3130 | mat a; nst-5RIP1; telVR::hph::T; trp-2 | this study |

| N3132 | mat a nst-3RIP1; nst-5RIP1; telVR::hph::T; nst-1RIP1 | this study |

| N3440* | mat A Δad-3A; Δmus-52::hph; hpoRIP2trp-2; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3441 | mat a; telVR::hph::T; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3442 | mat a; Δmus-52::hph;telVR::hph::T; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3443 | mat A; hpoRIP2; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3445 | mat A Δad-3A; nst-5RIP1; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3447 | mat A Δad-3A; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar Δdim-2::hph | this study |

| N3449 | mat A; dim-5 leu-2 pan-1; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3452 | mat a Δad-3A; nst-1RIP1trp-2; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3453 | mat a nst-2RIP1; trp-2; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3455 | mat a nst-3RIP1; trp-2; telVIIL::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3456* | mat A Δad-3A; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar; Δmus-52::hph; hpoRIP2trp-2 | this study |

| N3457 | mat a; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3459 | mat a; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar; Δmus-52::hph | this study |

| N3460 | mat A; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar; Δdim-2::hph | this study |

| N3462 | mat A; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar; dim-5 leu-2 pan-1 | this study |

| N3458 | mat A; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar; nst-1RIP1 | this study |

| N3464 | mat a nst-3RIP1; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar | this study |

| N3465 | mat A; telIIR::ad-3A+::bar; nst-5RIP1 | this study |

*primary heterokaryotic transformant

Protein sequences

Accession numbers for protein sequences in Figure 1 are as follows: S. cerevisiae Sir2p [GenBank:NP_010242]; N. crassa [GenBank:NST-1 XP_960372], NST-2 [GenBank:XP_963725], NST-3 [GenBank:XP_963711], NST-4 [GenBank:XP_959116], NST5 [GenBank:XP_956588], NST6 NCU05973.1 (this gene is misannotated in the current Broad database assembly) [49], NST7 [GenBank:XP_962799]; H. sapiens SIRT1 [GenBank:NP_036370], SIRT2 [GenBank:AAK51133], SIRT3 [GenBank:NP_036371], SIRT4 [GenBank:NP_036372], SIRT5 [GenBank:NP_036373], SIRT6 [GenBank:AAH28220], SIRT7 [GenBank:NP_057622].

Mutagenesis by RIP

The nst-1 gene was amplified from genomic DNA with primers nst-1-1 and nst-1-2 (all primer sequences are listed in Table 2). The BamHI+XbaI-digested PCR product was cloned into the BamHI+XbaI-digested his-3 targeting vector pBM61 [65], generating pBM61-Sir2. pBM61-Sir2 was linearized with NdeI and targeted to the his-3 locus in strain N1674 by electroporation [65]. A his-3+::nst-1 transformant was crossed to strain N593 and random progeny was analyzed for evidence of RIP by Southern blotting. The endogenous nst-1 locus from one strain (N2225) showed RsaI RFLPs and was sequenced to identify the RIP mutations.

Table 2.

Primer sequences

| Name | sequence |

| nst-1-1 | GCGGATCCGGTACAAACGGGCCGTTCTG |

| nst-1-2 | GTTCTAGACCTAACGAACCTAGCCGGACC |

| S2L1-EcoRI | TCGAATTCCAAGGCGAAACATCACGCTTATTCT |

| S2L1-SpeI | TGACTAGTTGATCACAGCCACCGAGATCGTCTG |

| S2L2-EcoRI | CAGAATTCATGGACTGCTTGCGACCGAAACCGTCCG |

| S2L2-NotI | CCGCGGCCGCGTCGATCAGATGCCCTATACCCCGAG |

| 203-4 | GGCGGATCCATGTCCCTAGCGACAACA |

| 203-5 | CCTTAATTAAGCGGACCCGTCCAGTAAACAA |

| ad-3AF | GCCGCGGCCGCAGTCAAATGGAAGACGGTGG |

| ad-3AR | GCCGGATCCTCAAAGCTCACCAAGGGC |

| Tel7L5FAatII | GCCGACGTCATTATAGGACGAAAAGGG |

| Tel7L5RPmlI | GCCCACGTGTTGACATAGGCACTTGCC |

| Tel7L3FBamHI | GCCGGATCCCGAGTCAGCAAGAAGTTTTG |

| Tel7L3REcoRI | GCCGAATTCGGTTGAGCGGGTAGTTCC |

| Tel2R5FAatII | GCCGACGTCAGATGCTTATACTTAGGG |

| Tel2R5RPmlI | GCCCACGTGCAAAAAGCAATAGGAGGG |

| Tel2R3FBamHI | GCCGGATCCCGTTATTCTAAAGGACCC |

| Tel2R3RecoRI | GCCGAATTCCTAGTATTGAAAGGGGAG |

| nst1BamHI | GCGGATCCCTGAAGCTTGCACTCCGGAGGAAGCGGTG |

| nst1NotI | CTGCGGCCGCGAATGAGTTGTGAAATACCCGATCCAAACC |

| hH4-1F | AACCACCGAAACCGTAGAGGGTAC |

| hH4-1R | ATCGCCGACACCGTGTGTTGTAAC |

| 8:F10F | GTAACGCAAATTCTAAAATTGCAATAC |

| 8:F10R | CTTAGTAATTAATTTAATACGTGCGCC |

| hphF | GACCCGGTCATACCTTCT |

| hphR | TTCCCCAATGTCAAGCAC |

| telILF | CTTCTTGCGTCTTGCCTGCTC |

| telILR | CCTTTTCGTTCGGTTGACAGC |

| telVILF | AACTTGGCACCCTCCGCGTT |

| telVILR | CCCCTCTAAGTTTTCCGATT |

The nst-2 gene was amplified from genomic DNA with primers S2L1-EcoRI and S2L1-SpeI, digested with EcoRI+SpeI, and cloned into EcoRI+SpeI-digested pBM61. The resulting plasmid, pBM61-S2L1, was linearized with NdeI and targeted to his-3 in strains N1445 and N1674. To mutate nst-3, the gene was amplified with primers S2L2-EcoRI and S2L2-Not1, digested with EcoRI+NotI, and cloned into EcoRI+NotI-digested pBM61. The resulting plasmid, pBM61-S2L2, was linearized with NdeI and targeted his-3 in strains N1445 and N1674. For both nst-2 and nst-3, His+ transformants of N1445 and N1674 were crossed to each other and progeny were analyzed for evidence of RIP by Southern blotting of RsaI-digested DNA; RIP mutated alleles were then sequenced.

The nst-5 gene was amplified with primers 203-4 and 203-5, digested with BamHI+PacI and inserted into BamHI+PacI-digested pMF272 [66]. The resulting plasmid, pKA13, was linearized with DraI and targeted to his-3 in strain N1674. A His+ transformant was crossed to strain N1447 and two progeny with duplications were then crossed to induce RIP. Southern analysis revealed RFLPs in strain N2681; thus the endogenous allele was sequenced.

Insertion of markers at telomeres

The bacterial hph gene under the control of the constitutive trpC promoter was removed from pCSN43 [67] by digestion with SalI and ligated to XhoI-digested pGRG-1/TYR103 [68] to generate pCM8. To generate pCM11, pCM8 was digested with PvuII and the hph fragment was ligated to HpaI-digested pNC36 [3], which contains the Pogo transposon from the subtelomere of linkage group VR. BsiWI-digested pCM11 was used to transform strain N1982 (derived from a cross between strains N2225 and N565, which was derived from a cross between strains N564 and N534). Correct integration at LG VR was confirmed by Southern blotting in the transformant, N2292, and this strain was backcrossed to strain N534 and WT (N2285). We identified nst-1RIP1 progeny that retained telVR::hph::T for further study (strains N2284, N2288). A Southern blot demonstrating subtelomeric integration is shown in Figure 3. The nst-3RIP1 allele was then introduced by crossing N2284 and N2634 to obtain strains N2635 and N2636. Strains N2288 and N2634 were also crossed to generate N2664, which was crossed to strains N1275 (dim-2), N2140 (dim-5), N2552 (hpo) and N2681 (nst-5) to introduce the designated mutation (yielding strains N2833, N2997, N3004, and 2693, respectively). N2633 (nst-2) was crossed to N2284 to generate N2667. N2636 was crossed to N2693 to generate the triple nst mutant, N3132. A nst+ strain (N3120) and nst-1RIP1 (N3125), nst-3RIP1 (N3132) and nst-5RIP1 (N3130) siblings from this cross were also selected for further study. Complete genotypes are listed in Table 1.

The ad-3A coding region with its promoter was amplified from genomic DNA with primers ad-3AF and ad-3AR. To generate pTTK17, the ad-3A PCR product was digested with NotI+BamHI and ligated to pBARKS1 [69] digested with the same enzymes. Plasmid pBARKS1 contains the bar gene under the control of the trpC promoter, which allows selection for glufosinate ('Basta') resistance. A region near Tel VIIL (324–1306 bp from the chromosome end) was amplified by PCR with primers Tel7L5FAatII and Tel7L5RPmlI, digested with PmlI+AatII and ligated to pTTK17 DNA that had been digested with the same enzymes, yielding plasmid pTTK18. A second region of Tel VIIL (1310–2319 bp from the chromosome end) was amplified with primers Tel7L3FBamHI and Tel7L3REcoRI, digested with BamHI+EcoRI and ligated to pTTK18 digested with the same enzymes, yielding the gene targeting vector pTTK19. AlwNI-linearized pTTK19 was transformed into N3017 and BastaR colonies were selected. Following confirmation of correct insertion by PCR analysis and Southern blotting (Figure 3), one transformant (N3440) was crossed to strains N2130 (nst-1), N2633 (nst-2), N2921 (nst-3), N2693 (nst-5), N1877 (dim-2), and N2264 (dim-5). Progeny that retained the bar marker at Tel VIIL but not the Δmus52::hph+ allele, and that also included the desired nst and dim mutations, were selected for further studies.

The same ad-3A bar construct was also targeted to the subtelomeric region of Tel IIR. A region near Tel IIR (1444–2472 bp from the chromosome end) was amplified with primers Tel2R3FBam and Tel2R3REco, digested with BamHI+EcoRI and ligated to pBARKS1 [69] digested with the same enzymes, yielding plasmid pTTK20. The ad-3A region was amplified and inserted into pTTK20 as described above, yielding pTTK21. A second region of Tel IIR (259–1278 bp from the chromosome end) was amplified with primers Tel2R5FAatII and Tel2R5RPmlI, digested with AatII+PmlI and ligated to pTTK21 DNA digested with the same enzymes, yielding gene targeting vector pTTK22. AlwNI-linearized pTTK22 was transformed into N3017 and BastaR colonies were selected. Following confirmation of correct insertion by PCR analysis and Southern blotting (Figure 3), one transformant (N3456) was crossed to strains N2130 (nst-1), N2633 (nst-2), N2921 (nst-3), N2693 (nst-5), N1275 (dim-2), and N2264 (dim-5). As above, progeny that retained the bar marker at Tel IIR but not the Δmus52::hph+ allele, and that also carried the desired nst and dim mutations were selected for further studies.

Telomeric silencing assay

Conidia from strain N3120 (telVR::hph+) or N3441 (tel VIIL::bar+) were collected in water from flasks containing Vogel's minimal medium, 2% sucrose, 1.5% agar and appropriate supplements after 1 week of growth at 32°C. Roughly 1000 conidia were spread on Vogel's minimal agar plates with 2% sorbose, 0.05% fructose and 0.05% glucose (FGS) and allowed to dry briefly. Nicotinamide was included in agar medium at 1 mg/ml. For the other drugs, 2 mm × 2 mm filter paper squares soaked with 0.5 μl 5-aza-cytidine (Sigma; 24 mM in H2O) or 2 μl Trichostatin A (Wako; 33 mM in DMSO) were placed in the center of the plate. After 5 hr at 32°C, 5 ml 0.7% top agar with 3 mg/ml Hygromycin B (Hyg; Hygrogold, InvivoGen) was overlaid for a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. For Basta selection, Vogel's salt solution with low nitrogen was used in all media [39]. For better imaging of smaller colonies on Basta selection plates we avoided top agar and instead 20 mg/ml Basta isolated from Rely (Bayer) [70] was poured in 5 ml of bottom agar, then 20 ml of non-selective media was overlaid for a final concentration of 4 mg/ml Basta. Plates were photographed after an additional 2 days of incubation at room temperature. To assay the effect of nicotinamide on expression of hph located at a telomere or at an interstitial location flanked by amRIP sequences, nicotinamide and Hyg were both added directly to agar medium and roughly 105 conidia were spread. Photographs were taken after 2 days of incubation at 32°C.

Spot tests of mutants

To assay Hyg resistance, conidia were collected in water from flasks containing Vogel's minimal medium, 2% sucrose, 1.5% agar plus supplements following 1 week of growth at 32°C. Conidial suspensions were counted in a hemocytometer and serial dilutions were plated on Vogel's FGS agar medium with the same supplements, in the presence or absence of 1 mg/ml Hyg. Strains were allowed to grow for 2 days at 32°C. To test Basta resistance [39], conidia were prepared as above and plated on supplemented Vogel's FGS media prepared with low nitrogen and 1.5% agar in the presence or absence of 2 mg/ml Basta.

Southern blots

Genomic DNA was isolated from 2-day cultures in Vogel's liquid medium as described [53]. Approximately 0.5 μg DNA was digested overnight with the designated restriction endonuclease and fractionated on 0.8% agarose gels. Transfer to nylon membranes and blotting were performed as described [53].

Western blots

Nuclei were isolated as described [71] with the addition of HDAC inhibitors, TSA (1 μM, Wako) and sodium butyrate (50 mM, J.T. Baker). Nuclear proteins were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Following transfer to PVDF membrane (Millipore Immobilon-P) in 10 mM N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (CAPS), pH 11 with 20% methanol, blots were probed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 3% non-fat dry milk with the following antibodies diluted as recommended by the manufacturer: α-H3 (Abcam ab1791), α-H3 acetyl K9 (Abcam ab4441), α-H3 acetyl K14 (Upstate 06–911), α-H3 acetyl K9/K14 (Upstate 06–599), α-H4 tetra-acetyl (Upstate 06–866) and α-H4 acetyl K16 (Upstate 07–329). Antibody detection was performed as described [25].

Histone deacetylase assays

NST-1 was expressed as a GST fusion protein for in vitro activity assays. The nst-1 coding region was amplified with primers Nst1BamHI and Nst1NotI, digested with BamHI+NotI and cloned into BamHI+NotI-digested pGEX-5X-2 (GE Healthcare). The protein was expressed in E. coli strain BL21, induced with IPTG and purified on glutathione agarose (Sigma) in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM DTT). Following elution with reduced glutathione, the GST fusion protein was dialyzed against RIPA buffer with 25% glycerol. In vitro activity assays were performed as described [15].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP experiments were performed as described [25] with the antibodies above and with α-H3 trimethyl K9 [72], α-H3 trimethyl K27 (Upstate 07–449), and α-H4 trimethyl K20 (Upstate 07–463). Primers used for the detection of precipitated DNA fragments are listed in Table 2. PCR reactions were repeated at least two times for each of two independent ChIP experiments.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KMS helped design the study, generated strains, performed silencing assays, spot tests, Western blots, southern blots, northern blots, ChIP assays, sequence alignments and drafted and revised the manuscript. GOK helped design the study, created nst mutants, performed silencing assays, and revised the manuscript. CBM helped conceive of and design the study and generated nst-1 and telomere targeted marker strains. TKK generated strains and performed Southern blots. KKA generated the nst-5 mutant. MH helped generate nst mutants. MF helped conceive of and design the study and revised the manuscript. MRM performed the in vitro deacetylase assays. EUS conceived of and helped design the study, and revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Jon Murphy, Adam Caccavano, and Jeewong Choi for technical assistance and Eric Gilson for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM025690-22 to EUS; GM61641 to Danesh Moazed) the National Science Foundation (MCB-0121383 to EUS), an American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship to KMS (PF-04-043-01-GMC), a Canadian Institute of Health Research postdoctoral fellowship to MRM and an American Cancer Society grant (RSG-08-030-01-CCG to M.F).

Contributor Information

Kristina M Smith, Email: smitkris@science.oregonstate.edu.

Gregory O Kothe, Email: gok1@psu.edu.

Cindy B Matsen, Email: cindy.matsen@hsc.utah.edu.

Tamir K Khlafallah, Email: tamir@molbio.uoregon.edu.

Keyur K Adhvaryu, Email: keyur@molbio.uoregon.edu.

Melissa Hemphill, Email: mahemphill@gmail.com.

Michael Freitag, Email: freitagm@cgrb.oregonstate.edu.

Mohammad R Motamedi, Email: mmotamedi@hms.harvard.edu.

Eric U Selker, Email: selker@uoregon.edu.

References

- Blasco MA. The epigenetic regulation of mammalian telomeres. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrg2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley R, Chan C, Tye B, Petes T. Unusual DNA sequences associated with the ends of yeast chromosomes. Nature. 1984;310:157–160. doi: 10.1038/310157a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechtman MG. Isolation of telomere DNA from Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3168–3177. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JM, Biessmann H. The unusual telomeres of Drosophila. Trends Genet. 1995;11:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)88998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler KS, Wakimoto BT. Heterochromatin and gene expression in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genetics. 1995;29:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.003045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryde FE, Louis EJ. Limitations of silencing at native yeast telomeres. EMBO J. 1999;18:2538–2550. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar A. Dosage compensation: an intertwined world of RNA and chromatin remodelling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AB, Kaback DB. Telomeric silencing of an open reading frame in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2006;173:1169–1173. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrod S, Gasser SM. Long-range silencing and position effects at telomeres and centromeres: parallels and differences. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2303–2318. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3246-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti P, Freeman K, Coodly L, Shore D. Evidence that a complex of SIR proteins interacts with the silencer and telomere-binding protein RAP1. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2257–2269. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell M, Palladino F, Laroche T, Kyrion G, Liu C, Lustig AJ, Gasser SM. The carboxy termini of Sir4 and Rap1 affect Sir3 localization: evidence for a multicomponent complex required for yeast telomeric silencing. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:909–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander G, Guarente L. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:417–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanny JC, Kirkpatrick DS, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Budding yeast silencing complexes and regulation of Sir2 activity by protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6931–6946. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.6931-6946.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaranarayana GD, Motamedi MR, Moazed D, Grewal SI. Sir2 regulates histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1240–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00489-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman-Cook LL, Gomez EB, Spedale EJ, Marlett J, Forsburg SL, Pillus L, Laurenson P. Conserved locus-specific silencing functions of Schizosaccharomyces pombe sir2+ Genetics. 2005;169:1243–1260. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh J, Sadaie M, Urano T, Ishikawa F. Telomere binding protein Taz1 establishes Swi6 heterochromatin independently of RNAi at telomeres. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1808–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JM, Konev AY, Biessmann H. Telomeric position effect in Drosophila melanogaster reflects a telomere length control mechanism. Genetica. 2003;117:319–325. doi: 10.1023/a:1022925003172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrini B, Piacentini L, Fanti L, Altieri F, Chichiarelli S, Berloco M, Turano C, Ferraro A, Pimpinelli S. HP1 controls telomere capping, telomere elongation, and telomere silencing by two different mechanisms in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2004;15:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessmann H, Prasad S, Semeshin VF, Andreyeva EN, Nguyen Q, Walter MF, Mason JM. Two distinct domains in Drosophila melanogaster telomeres. Genetics. 2005;171:1767–1777. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.048827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti L, Pimpinelli S. HP1: a functionally multifaceted protein. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MI, Parkhurst SM. Drosophila Sir2 is required for heterochromatic silencing and by euchromatic Hairy/E(Spl) bHLH repressors in segmentation and sex determination. Cell. 2002;109:447–458. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00732-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzminova EA, Selker EU. Dim-2 encodes a DNA-methyltransferase responsible for all known cytosine methylation in Neurospora. EMBO J. 2001;20:4309–4323. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H, Selker EU. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2001;414:277–283. doi: 10.1038/35104508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H, Zhang X, McMillen D, Singh PB, Nakayama J, Grewal SI, Allis CD, Cheng X, Selker EU. Trimethylated lysine 9 of histone H3 is a mark for DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nat Genet. 2003;34:75–79. doi: 10.1038/ng1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M, Hickey PC, Khlafallah TK, Read ND, Selker EU. HP1 is essential for DNA methylation in Neurospora. Mol Cell. 2004;13:427–434. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker EU, Tountas NA, Cross SH, Margolin BS, Murphy JG, Bird AP, Freitag M. The methylated component of the Neurospora crassa genome. Nature. 2003;422:893–897. doi: 10.1038/nature01564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambareri EB, Aisner R, Carbon J. Structure of the chromosome VII centromere region in Neurospora crassa: degenerate transposons and simple repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5465–5477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechtman MG. Characterization of telomere DNA from Neurospora crassa. Gene. 1990;88:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90027-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshire R, Selker EU. Fungal models for epigenetic research: Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Neurospora crassa. In: Allis TJCD, Reinberg D, editor. Epigenetics. USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2007. pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovich KA, Alex LA, Yarden O, Freitag M, Turner GE, Read ND, Seiler S, Bell-Pedersen D, Paietta J, Plesofsky N, Plamann M, Goodrich-Tanrikulu M, Schulte U, Mannhaupt G, Nargang FE, Radford A, Selitrennikoff C, Galagan JE, Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, Catcheside D, Inoue H, Aramayo R, Polymenis M, Selker EU, Sachs MS, Marzluf GA, Paulsen I, Davis R, Ebbole DJ, Zelter A, Kalkman ER, O'Rourke R, Bowring F, Yeadon J, Ishii C, Suzuki K, Sakai W, Pratt R. Lessons from the genome sequence of Neurospora crassa: tracing the path from genomic blueprint to multicellular organism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:1–108. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.1.1-108.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4623–4635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Sherman JM, Devine SE, Cameron EE, Pillus L, Boeke JD. The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2888–2902. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Zhang Q, Zhang K, Xie W, Grunstein M. Sir2 deacetylates histone H3 lysine 56 to regulate telomeric heterochromatin structure in yeast. Mol Cell. 2007;27:890–900. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas NL, Miller KM, DeFazio LG, Toczyski DP. Cell cycle and checkpoint regulation of histone H3 K56 acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4. Mol Cell. 2006;23:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrod S, Cockell MM, Laroche T, Renauld H, Ducrest AL, Bonnard C, Gasser SM. A cytosolic NAD-dependent deacetylase, Hst2p, can modulate nucleolar and telomeric silencing in yeast. Embo J. 2001;20:197–209. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, Fahie K, Christodoulou DC, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Karow M, Blander G, Wolberger C, Prolla TA, Weindruch R, Alt FW, Guarente L. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 2006;126:941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker EU. Repeat-induced gene silencing in fungi. Adv Genet. 2002;46:439–450. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(02)46016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pall ML. The use of Ignite (Basta; glufosinate; phosphinothricin) to select transformants of bar-containing plasmids in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1993;40:58. [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya Y, Suzuki K, Ishii C, Inoue H. Highly efficient gene replacements in Neurospora strains deficient for nonhomologous end-joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12248–12253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402780101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riha K, Heacock ML, Shippen DE. The role of the nonhomologous end-joining DNA double-strand break repair pathway in telomere biology. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:237–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolis KG, Nimmo ER, Hartsuiker E, Carr AM, Jeggo PA, Allshire RC. Novel functional requirements for non-homologous DNA end joining in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Embo J. 2001;20:210–221. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Kijima M, Akita M, Beppu T. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17174–17179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker EU. Trichostatin A causes selective loss of DNA methylation in Neurospora. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9430–9435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45099–45107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irelan JT, Selker EU. Cytosine methylation associated with repeat-induced point mutation causes epigenetic gene silencing in Neurospora crassa. Genetics. 1997;146:509–23. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowsky V, Kaldenhoff R, Ricci M, Russo VEA. Fast and reliable mini-prep RNA extraction from Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1990;36:41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rountree MR, Selker EU. DNA methylation inhibits elongation but not initiation of transcription in Neurospora crassa. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2383–2395. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurospora crassa Database http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/neurospora/Home.html

- Pryde FE, Gorham HC, Louis EJ. Chromosome ends: all the same under their caps. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:822–828. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker EU. DNA methylation and chromatin structure: a view from below. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90193-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MJ, Marcotte BA, Selker EU. DNA methylation associated with repeat-induced point mutation in Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5586–5597. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao VP, Freitag M, Selker EU. Short TpA-rich segments of the zeta-eta region induce DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:249–273. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H, Selker EU. Synthesis of signals for de novo DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2379–2394. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2379-2394.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KR, Burns G, Mata J, Volpe TA, Martienssen RA, Bahler J, Thon G. Global effects on gene expression in fission yeast by silencing and RNA interference machineries. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:590–601. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.590-601.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KR, Ibarra PT, Thon G. Evolutionary-conserved telomere-linked helicase genes of fission yeast are repressed by silencing factors, RNAi components and the telomere-binding protein Taz1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:78–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koering CE, Pollice A, Zibella MP, Bauwens S, Puisieux A, Brunori M, Brun C, Martins L, Sabatier L, Pulitzer JF, Gilson E. Human telomeric position effect is determined by chromosomal context and telomeric chromatin integrity. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1055–1061. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michishita E, McCord RA, Berber E, Kioi M, Padilla-Nash H, Damian M, Cheung P, Kusumoto R, Kawahara TL, Barrett JC, Chang HY, Bohr VA, Ried T, Gozani O, Chua KF. SIRT6 is a histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylase that modulates telomeric chromatin. Nature. 2008;452:492–496. doi: 10.1038/nature06736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram M, Sprung CN, Gao Q, Lo AW, Reynolds GE, Murnane JP. Telomere position effect and silencing of transgenes near telomeres in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1865–1878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1865-1878.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cao M, O'Sullivan R, Peters AH, Jenuwein T, Blasco MA. Epigenetic regulation of telomere length in mammalian cells by the Suv39h1 and Suv39h2 histone methyltransferases. Nat Genet. 2004;36:94–99. doi: 10.1038/ng1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y, Xu JF, Chavez L, Riethman HC, Lansdorp PM, Weng NP. Telomere length and the expression of natural telomeric genes in human fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1329–1336. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irelan JT, Hagemann AT, Selker EU. High frequency repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) is not associated with efficient recombination in Neurospora. Genetics. 1994;138:1093–1103. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays SM, Swanson J, Selker EU. Identification and characterization of the genes encoding the core histones and histone variants of Neurospora crassa. Genetics. 2002;160:961–973. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.3.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RH. Neurospora: Contributions of a Model Organism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin BS, Freitag M, Selker EU. Improved plasmids for gene targeting at the his-3 locus of Neurospora crassa by electroporation. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1997;44:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M, Hickey PC, Raju NB, Selker EU, Read ND. GFP as a tool to analyze the organization, dynamics and function of nuclei and microtubules in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41:897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staben C, Jensen B, Singer M, Pollock J, Schechtman M, Kinsey J, Selker E. Use of a bacterial Hygromycin B resistance gene as a dominant selectable marker in Neurospora crassa transformation. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1989;36:79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kothe G, Deak M, Free SJ. Use of the Neurospora tyrosinase gene as a reporter gene in transformation experiments. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1993;40:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pall ML, Brunelli JP. A series of six compact fungal transformation vectors containing polylinkers with multiple unique restriction sites. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1993;40:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hays S, Selker E. Making the selectable marker bar tighter and more economical. Fungal Genet Newsl. 2000;47:107. [Google Scholar]

- Baum JA, Giles NH. DNase I hypersensitive sites within the inducible qa gene cluster of Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6533–6537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]