Abstract

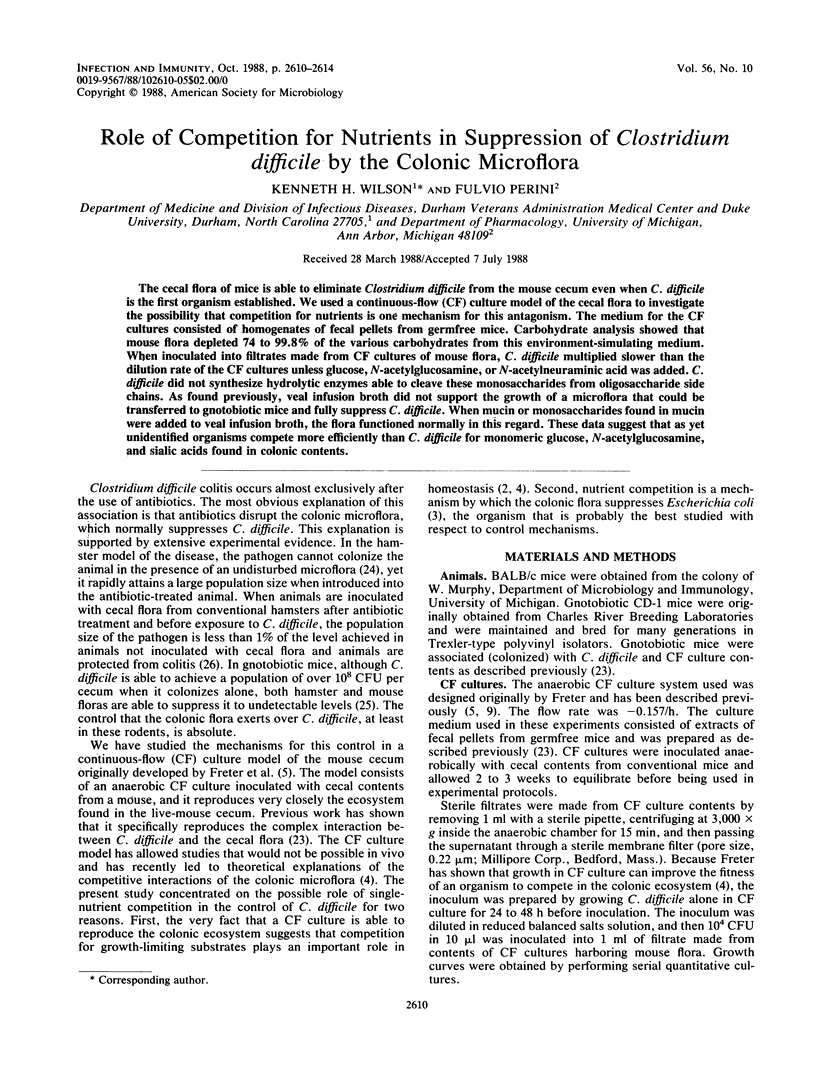

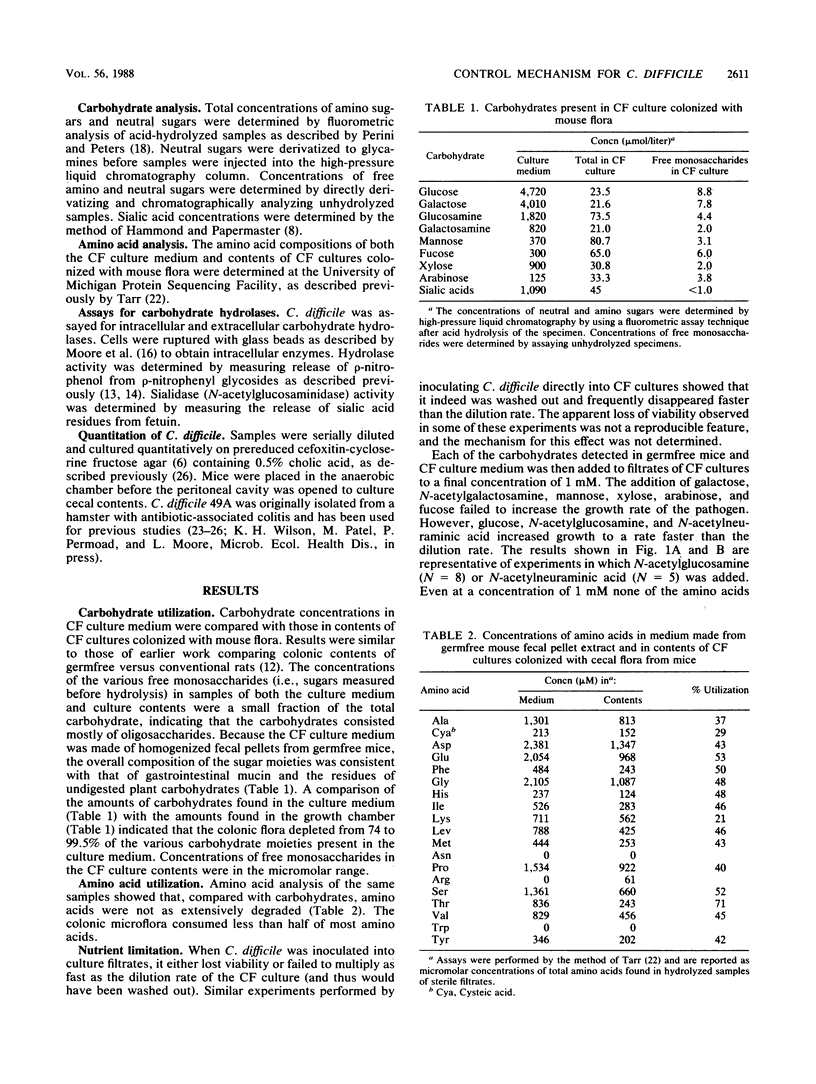

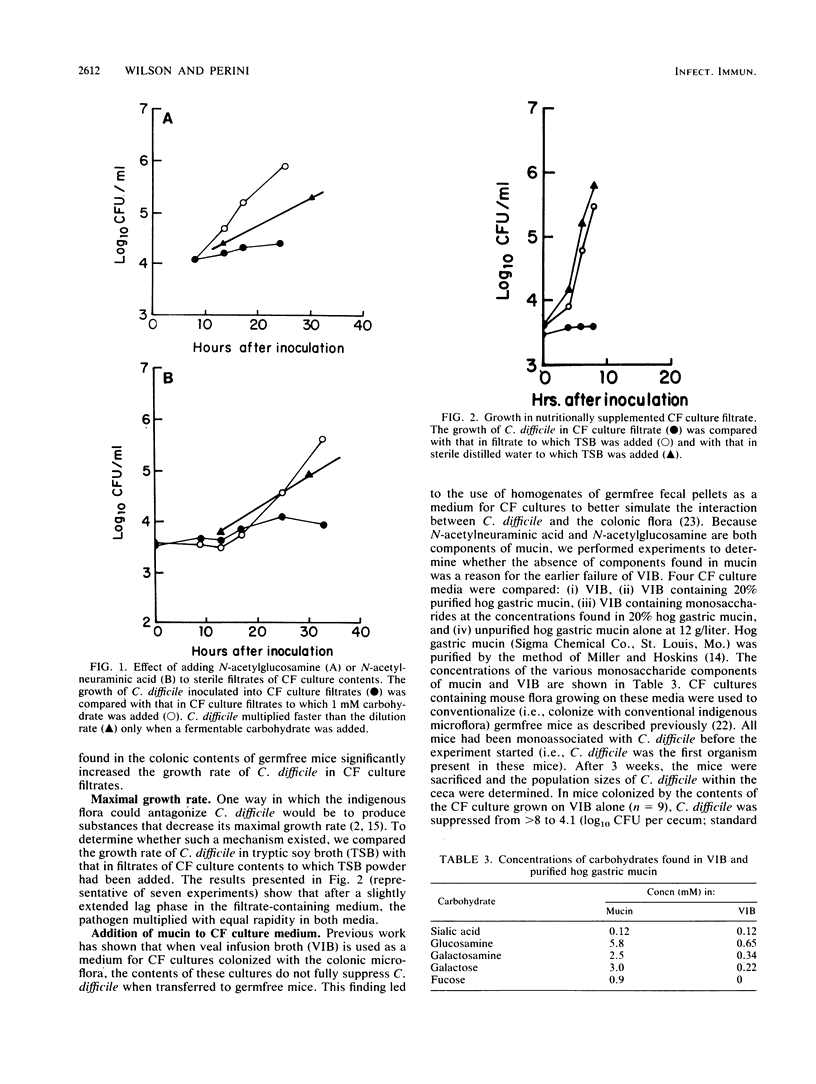

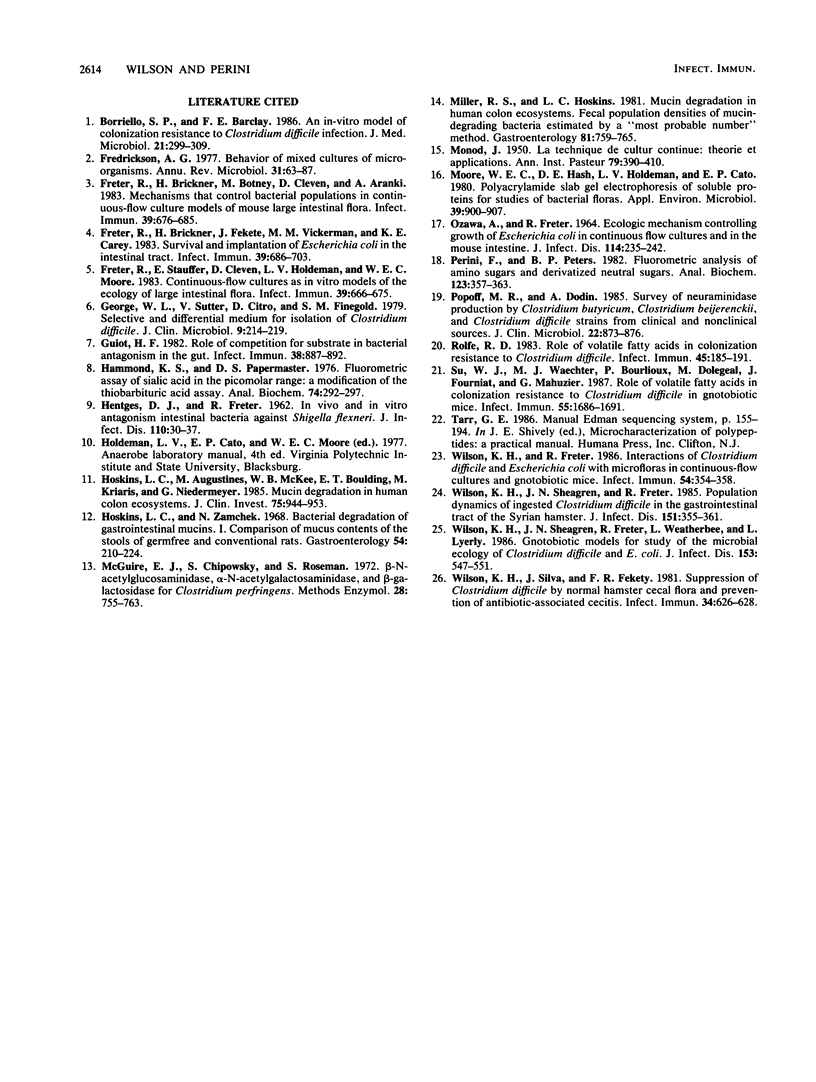

The cecal flora of mice is able to eliminate Clostridium difficile from the mouse cecum even when C. difficile is the first organism established. We used a continuous-flow (CF) culture model of the cecal flora to investigate the possibility that competition for nutrients is one mechanism for this antagonism. The medium for the CF cultures consisted of homogenates of fecal pellets from germfree mice. Carbohydrate analysis showed that mouse flora depleted 74 to 99.8% of the various carbohydrates from this environment-simulating medium. When inoculated into filtrates made from CF cultures of mouse flora, C. difficile multiplied slower than the dilution rate of the CF cultures unless glucose, N-acetylglucosamine, or N-acetylneuraminic acid was added. C. difficile did not synthesize hydrolytic enzymes able to cleave these monosaccharides from oligosaccharide side chains. As found previously, veal infusion broth did not support the growth of a microflora that could be transferred to gnotobiotic mice and fully suppress C. difficile. When mucin or monosaccharides found in mucin were added to veal infusion broth, the flora functioned normally in this regard. These data suggest that as yet unidentified organisms compete more efficiently than C. difficile for monomeric glucose, N-acetylglucosamine, and sialic acids found in colonic contents.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Borriello S. P., Barclay F. E. An in-vitro model of colonisation resistance to Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Microbiol. 1986 Jun;21(4):299–309. doi: 10.1099/00222615-21-4-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson A. G. Behavior of mixed cultures of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:63–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freter R., Brickner H., Botney M., Cleven D., Aranki A. Mechanisms that control bacterial populations in continuous-flow culture models of mouse large intestinal flora. Infect Immun. 1983 Feb;39(2):676–685. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.676-685.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freter R., Brickner H., Fekete J., Vickerman M. M., Carey K. E. Survival and implantation of Escherichia coli in the intestinal tract. Infect Immun. 1983 Feb;39(2):686–703. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.686-703.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freter R., Stauffer E., Cleven D., Holdeman L. V., Moore W. E. Continuous-flow cultures as in vitro models of the ecology of large intestinal flora. Infect Immun. 1983 Feb;39(2):666–675. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.666-675.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George W. L., Sutter V. L., Citron D., Finegold S. M. Selective and differential medium for isolation of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1979 Feb;9(2):214–219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.2.214-219.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiot H. F. Role of competition for substrate in bacterial antagonism in the gut. Infect Immun. 1982 Dec;38(3):887–892. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.3.887-892.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENTGES D. J., FRETER R. In vivo and in vitro antagonism of intestinal bacteria against Shigella flexneri. I. Correlation between various tests. J Infect Dis. 1962 Jan-Feb;110:30–37. doi: 10.1093/infdis/110.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond K. S., Papermaster D. S. Fluorometric assay of sialic acid in the picomole range: a modification of the thiobarbituric acid assay. Anal Biochem. 1976 Aug;74(2):292–297. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins L. C., Agustines M., McKee W. B., Boulding E. T., Kriaris M., Niedermeyer G. Mucin degradation in human colon ecosystems. Isolation and properties of fecal strains that degrade ABH blood group antigens and oligosaccharides from mucin glycoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1985 Mar;75(3):944–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI111795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins L. C., Zamcheck N. Bacterial degradation of gastrointestinal mucins. I. Comparison of mucus constituents in the stools of germ-free and conventional rats. Gastroenterology. 1968 Feb;54(2):210–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. S., Hoskins L. C. Mucin degradation in human colon ecosystems. Fecal population densities of mucin-degrading bacteria estimated by a "most probable number" method. Gastroenterology. 1981 Oct;81(4):759–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W. E., Hash D. E., Holdeman L. V., Cato E. P. Polyacrylamide slab gel electrophoresis of soluble proteins for studies of bacterial floras. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980 Apr;39(4):900–907. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.4.900-907.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OZAWA A., FRETER R. ECOLOGICAL MECHANISM CONTROLLING GROWTH OF ESCHERICHIA COLI IN CONTINUOUS FLOW CULTURES AND IN THE MOUSE INTESTINE. J Infect Dis. 1964 Jun;114:235–242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/114.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perini F., Peters B. P. Fluorometric analysis of amino sugars and derivatized neutral sugars. Anal Biochem. 1982 Jul 1;123(2):357–363. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoff M. R., Dodin A. Survey of neuraminidase production by Clostridium butyricum, Clostridium beijerinckii, and Clostridium difficile strains from clinical and nonclinical sources. J Clin Microbiol. 1985 Nov;22(5):873–876. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.5.873-876.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe R. D. Role of volatile fatty acids in colonization resistance to Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1984 Jul;45(1):185–191. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.185-191.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W. J., Waechter M. J., Bourlioux P., Dolegeal M., Fourniat J., Mahuzier G. Role of volatile fatty acids in colonization resistance to Clostridium difficile in gnotobiotic mice. Infect Immun. 1987 Jul;55(7):1686–1691. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.7.1686-1691.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. H., Freter R. Interaction of Clostridium difficile and Escherichia coli with microfloras in continuous-flow cultures and gnotobiotic mice. Infect Immun. 1986 Nov;54(2):354–358. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.354-358.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. H., Sheagren J. N., Freter R. Population dynamics of ingested Clostridium difficile in the gastrointestinal tract of the Syrian hamster. J Infect Dis. 1985 Feb;151(2):355–361. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. H., Sheagren J. N., Freter R., Weatherbee L., Lyerly D. Gnotobiotic models for study of the microbial ecology of Clostridium difficile and Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1986 Mar;153(3):547–551. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. H., Silva J., Fekety F. R. Suppression of Clostridium difficile by normal hamster cecal flora and prevention of antibiotic-associated cecitis. Infect Immun. 1981 Nov;34(2):626–628. doi: 10.1128/iai.34.2.626-628.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]