Abstract

Lyme borreliae naturally maintain numerous distinct DNA elements of the cp32 family, each of which carries a mono- or bicistronic erp locus. The encoded Erp proteins are surface-exposed outer membrane lipoproteins that are produced at high levels during mammalian infection but largely repressed during colonization of vector ticks. Recent studies have revealed that some Erp proteins can serve as bacterial adhesins, binding host proteins such as the complement regulator factor H and the extracellular matrix component laminin. These results suggest that Erp proteins play roles in multiple aspects of mammalian infection.

Keywords: Borrelia burgdorferi, Outer surface protein, Adhesin, Complement, Factor H, Laminin

Introduction

All examined Lyme borreliosis spirochetes contain numerous distinct DNA elements (Casjens et al., 2006). The Borrelia burgdorferi type strain, B31, is known to carry at least 25 separate DNA species, ranging from the ~950 kb main chromosome to the ~5 kb plasmid lp5 (Casjens et al., 1997, 2000; Fraser et al., 1997; Miller et al., 2000). Naturally-occurring, infectious isolates contain between 6 and 10 distinct, but homologous, DNA elements called cp32s (Simpson et al., 1990; Porcella et al., 1996; Stevenson et al., 1996, 2001; Zückert and Meyer, 1996; Casjens et al., 1997, 2000, 2006; Akins et al., 1999; Iyer et al., 2003; Stevenson and Miller, 2003). Members of the cp32 family have been identified in all examined Lyme disease-associated spirochetes, including those of the species B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, B. spielmanii, and B. afzelii (our unpublished results and Stevenson et al., 2006). Most cp32 elements are circular episomes of approximately 32 kb in size, although some naturally-occurring mutant cp32s have been identified, such as truncated 18 kb plasmids of B. burgdorferi strains N40 and 297 and a 56 kb linear cp32-hybrid plasmid of strain B31 (Stevenson et al., 1997; Caimano et al., 2000; Casjens et al., 2000). Several lines of evidence suggests that cp32 elements are bacteriophage genomes, although no one has yet isolated a borreliaphage and shown it to be encoded by cp32 genes (Casjens et al., 1997, 2000; Eggers and Samuels, 1999; Damman et al., 2000; Eggers et al., 2001; Zhang and Marconi, 2005).

All members of the cp32 family contain one mono- or bicistronic erp locus, the sequences of which generally vary among the different cp32s within an individual bacterium, and also between bacterial strains (Table 1) (Stevenson et al., 2001, 2006). All erp loci are preceded by nearly identical DNA sequences that include the transcriptional promoter and binding sites for at least three distinct DNA-binding proteins (Marconi et al., 1996; Stevenson et al., 1996, 2001; Babb et al., 2004, 2006). As would be expected from the extensive identities of erp promoter/operator sequences, almost all analyzed erp genes follow the same expression patterns in vitro and in vivo (Stevenson et al., 1995, 1998a; El-Hage and Stevenson, 2002; Hefty et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2003). The exceptions to the consensus pattern may reflect promoter mutations among those erp loci and/or allelic variations among regulatory factors (Akins et al., 1995; Suk et al., 1995; Hefty et al., 2001; Eggers et al., 2004, 2006). The significance of such variations has yet to be determined. In general, however, Erp proteins are synthesized during mammalian infection but repressed during colonization of the vector tick (Das et al., 1997; Gilmore et al., 2001; McDowell et al., 2001; Hefty et al., 2002; Liang et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2003, 2005, 2006; Miller and Stevenson, 2006).

Table 1.

B. burgdorferi cp32 plasmids and their associated erp loci. Various naming schemes have been applied to these genes by their discoverers, resulting in similar genes often having dissimilar names.

| Plasmid groupa | B31 | BL206 | N40 | Sh-2-82 | 297 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cp32-1 | erpAB | – | – | erp41, 42 | ospE, elpB1 |

| cp32-2/7 | erpCD or erpLMb | erpCD | ospEF | erp43 | elpA2 |

| cp32-3 | erpG | erpG | – | erp44 | ospF |

| cp32-4 | erpHY | erpHY | erp23, 24 | erp45 | elpA1 |

| cp32-5 | erpABc | erpAB | erp25 | erp41, 42 | ospE, elpB1 |

| cp32-6 | erpK | erpK | – | erp46 | bbk2.10 |

| cp32-8 | erpABc | – | – | erp50, 51 | – |

| cp32-9 | erpPQ | erpPQ | p21, erp22 | erp47, 48 | p21, elpB2 |

| cp32-10 | erpX | erpX | erp26 | – | – |

| cp32-11 | – | erpAB | – | erp49 | bbk2.11 |

| cp32-12 | – | – | erp27 | erp41, 42 | ospE, elpB1 |

– Not detected

Unified cp32 nomenclature as previously described (Stevenson et al., 1996, 2001; Casjens et al., 1997, 2006; Stevenson and Miller, 2003). Some earlier descriptions of strain 297 utilized a different naming system (Akins et al., 1999; Caimano et al., 2000; Stevenson et al., 2001).

Two distinct plasmids of group cp32-2 have been identified in strain B31.

The identical erp loci of strain B31 cp32-5 and cp32-8 were formerly designated erpIJ and erpNO, respectively (Casjens et al., 1997, 2000).

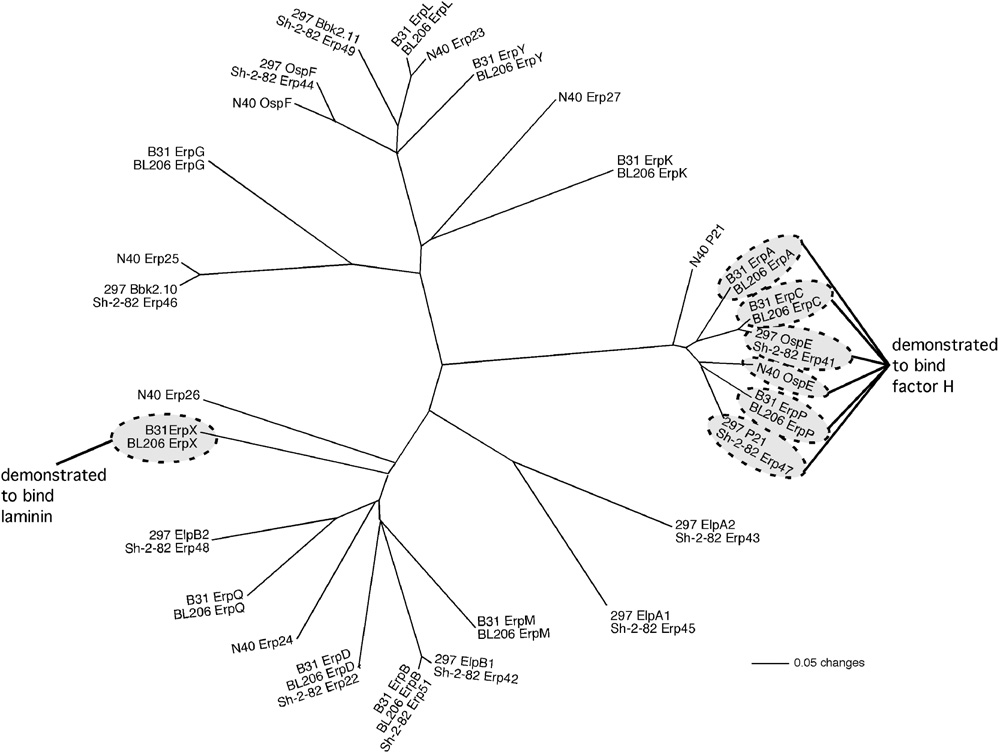

erp genes and their encoded proteins often differ widely in their sequences (Fig. 1). These differences have led to proposals that this family could be divided into three or more groups, each with a different name (Akins et al., 1999). However, since these genes and proteins share many unifying features, we continue to use the single name erp. Please see Stevenson et al. (2006) for a comprehensive review of the similarities and differences between erp genes and Erp proteins. Variations among erp sequences have proven valuable for studies of B. burgdorferi genetic exchange and recombination. An individual spirochete may contain several different cp32 elements that each carry an identical erp locus, such as the erpAB loci on the cp32-1, cp32-5, and cp32-8 elements of B. burgdorferi type strain B31, which are evidence of genetic shuffling within bacteria (Casjens et al., 1997, 2000; Stevenson et al., 1998a; Stevenson and Miller, 2003). In addition, some B. burgdorferi isolates are genetically distinct at numerous loci, yet contain some identical erp genes, indications that cp32s and erp genes are naturally transmitted horizontally among different bacteria (Stevenson et al., 1998b; Stevenson and Miller, 2003; Stevenson, Cooley and Woodman, submitted). In all, strain B31 is known to contain 10 distinct cp32 family members, encoding 13 different Erp proteins (Stevenson et al., 1996; Casjens et al., 1997, 2000).

Fig. 1.

Unrooted phylogram of predicted amino acid sequences of the Erp proteins encoded by the fully-characterized B. burgdorferi strains B31, BL206, N40, Sh-2-82, and 297 (Table 1) and prepared using PAUP* version 4.0b10 (Swofford, 2000). Most of the erp genes of strains Sh-2-82 and 297 are completely identical to each other, as are also the erp genes of strains B31 and BL206 (our unpublished results and Stevenson and Miller, 2003). A closely-related subset of Erp proteins have been shown to bind mammalian factor H in vitro under physiologically relevant conditions. Of those, the B31/BL206 ErpA, ErpC, and ErpP proteins have also been demonstrated to bind human FHR-1. Only the B31/BL206 ErpX protein is known to bind mammalian laminin. Please see text for details and references. Functions for other Erp proteins have yet to be determined.

Especially relevant to this review, all Erp proteins are surface-exposed outer membrane lipoproteins (Lam et al., 1994; El-Hage et al., 2001; Hefty et al., 2002). These proteins are therefore positioned to interact with the bacteria’s environment. As we describe below, the known functions of Erp proteins all involve binding of vertebrate host proteins.

Erp binding of host factor H

As an infected tick feeds on its host, Lyme borreliosis spirochetes are transmitted directly into the blood pool at the tick bite site. Bacteria then spread via the bloodstream and by invasion of host tissues to establish a chronic, disseminated infection (Cassatt et al., 1998; Stanek and Strle, 2003; Wormser, 2006). Spirochetes may later be acquired by additional ticks as they take a blood meal from the infected host. As are many other pathogenic microorganisms, B. burgdorferi is naturally resistant to the innate immune system of its hosts. As an example, fewer than 20 bacteria can be sufficient to infect immunocompetent animals (Barthold, 1991). The alternative pathway of complement activation is an important arm of vertebrate innate immunity, which rapidly clears susceptible microorganisms from the host in the absence of antibody. In culture, most infectious isolates of B. burgdorferi are resistant to their hosts’ alternative pathway of complement activation (Kochi et al., 1991; Brade et al., 1992; Breitner-Ruddock et al., 1997; van Dam et al., 1997; Kurtenbach et al., 1998, 2002). That characteristic is associated with binding of the host complement regulator factor H, enhanced breakdown of C3b and the C3bBb convertase, and prevention of membrane-attack complex formation (Alitalo et al., 2001; Kraiczy et al., 2001b). Serum-resistant B. burgdorferi produce several distinct outer-surface proteins during culture, termed BbCRASPs (B. burgdorferi complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins), that can bind host factor H (Kraiczy et al., 2001a, 2001b). The ability of B. burgdorferi to bind host factor H to its surface is apparently not the only mechanism by which Lyme borreliosis spirochetes evade host complement in vivo, since mice deficient in factor H can be infected to degrees equal to those of wild-type animals (Woodman et al., 2007).

A number of studies have demonstrated that a specific subset of the Erp family is capable of binding mammalian factor H under physiological conditions. The ErpA, ErpC, and ErpP proteins of type strain B31 exhibit significant affinities for factor H (Hellwage et al., 2001; Alitalo et al., 2002, 2004; Stevenson et al., 2002; Kraiczy et al., 2003, 2004a; Metts et al., 2003). Those proteins are identical to three proteins identified in B. burgdorferi strains ZS7 and LW2, named BbCRASP-3 (ErpP), BbCRASP-4 (ErpC), and BbCRASP-5 (ErpA) (Kraiczy et al., 2001a, 2004a). The ErpA, ErpC, and ErpP proteins are very similar to each other, sharing approximately 90% amino acid sequence identities (Fig. 1). Several very similar Erp proteins produced by other B. burgdorferi strains are also known to efficiently bind factor H, including the OspE protein of strain N40 and the P21 protein of strain 297 (Fig. 1) (Akins et al., 1999; Hellwage et al., 2001; Alitalo et al., 2002). Strain B31 carries three identical copies of erpA, on cp32-1, cp32-5, and cp32-8, and one copy each of erpC and erpP on cp32-2 and cp32-9, respectively (Stevenson et al., 1996; Casjens et al., 1997, 2000). Other strains of B. burgdorferi also carry multiple copies of identical genes that encode factor H-binding Erp proteins, the significance of which has yet to be explored (our unpublished results and Stevenson and Miller, 2003).

Mutagenesis studies have demonstrated that the carboxy-terminus and several internal amino acid motifs of ErpA/ErpC/ErpP/P21/OspE play roles in binding factor H (Alitalo et al., 2002, 2004; Kraiczy et al., 2003; Metts et al., 2003). Whether the identified residues directly interact with factor H or if they are instead required only for correct folding of the Erp proteins remains to be determined. Computer modeling suggested that these Erp proteins may form coiled-coil structures, a prediction that has yet to be tested experimentally (McDowell et al., 2004).

Other members of the Erp protein family also bind factor H in vitro, although those interactions appear to be too weak to be of biological significance (Alitalo et al., 2002; Stevenson et al., 2002; Hovis et al., 2006). In particular, ErpX can bind factor H in vitro, but only at non-physiological pH (Alitalo et al., 2002; Stevenson et al., 2002).

Serum-resistant B. burgdorferi produce two additional factor H-binding proteins during cultivation, named BbCRASP-1 and BbCRASP-2. Those outer membrane proteins are encoded by two distinct, unrelated genes named cspA (BbCRASP-1) and cspZ (BbCRASP-2) (Casjens et al., 2000; Kraiczy et al., 2001a, 2001b, 2002b, 2006; McDowell et al., 2003; Wallich et al., 2005; Hartmann et al., 2006). Factor H consists of 20 repeated motifs, termed short consensus repeats (SCRs) (Zipfel et al., 2002). Erp proteins bind to the carboxy-terminal SCR-20, which is also a major heparin-binding domain of factor H (Hellwage et al., 2001, 2002; Kraiczy et al., 2001a, 2001b, 2002b; Zipfel et al., 2002; Cheng et al., 2006). In contrast, BbCRASPs-1 and -2 both bind primarily to SCR-7 (Kraiczy et al., 2001a, 2001b, 2002b, 2004b; Hartmann et al., 2006). Those different affinities may have important consequences. Factor H in solution folds upon itself, with the carboxy-terminal SCRs exposed but SCR-7 is apparently buried. However, binding of factor H to adhesins via its carboxy-terminus uncoils the protein, which permits interactions between SCR-7 and its ligands (Aslam and Perkins, 2001; Oppermann et al., 2006). Presumably due to the structure of factor H in solution, the carboxy-terminal SCRs provide initial binding of factor H to mammalian cells (Prodinger et al., 1998; Perkins and Goodship, 2002; Jokiranta et al., 2005; Oppermann et al., 2006; Jószi et al., 2007). By analogy, Erp proteins may provide initial contact between the bacteria and factor H through SCR-20, causing the structure of factor H to open up and permit BbCRASPs-1 and/or -2 to bind the host protein more tightly via SCR-7. Cultured cspA− cspZ+ erp+ B. burgdorferi are very sensitive to killing by the alternative complement pathway (Patarakul et al., 1999; Brooks et al., 2005), and complementation of a cspA− mutant with a copy of the wild-type gene can restore in vitro complement resistance (Brooks et al., 2005). Erp proteins by themselves do not provide complement resistance to cultured B. burgdorferi. For examples, a mutant of strain B31 named B31-e2 lacks all BbCRASP-encoding genes except cspA plus one copy of erpA, but is as resistant to complement as its wild-type parent, while a sibling cspA− cspZ− mutant named B313 carries erpC and one copy of erpA, but is sensitive to in vitro killing by complement (Hartmann et al., 2006, and our unpublished results). Transformation of mutant B313 with a wild-type cspZ gene provided resistance to complement in vitro, indicating that BbCRASP-2 can play a role in protecting against complement-mediated killing (Hartmann et al., 2006). However, there are two important caveats to the above-described studies of cultured Lyme borreliosis spirochetes. First, studies have never been performed on erp-deficient bacteria to examine the abilities of BbCRASPs-1 or -2 to function in the complete absence of Erp proteins, so the possibility of cooperation between those proteins cannot be ruled out. Second, the relative importance of each gene during infection processes is unknown, since neither cspA, cspZ, nor all the erp genes have been deleted from an otherwise infectious bacterium.

As noted above, mice lacking the factor H gene (Cfh−/−) are infected to the same extents as are congenic wild-type mice (Woodman et al., 2007). Those results indicate that the ability of B. burgdorferi to bind factor H to its surface is redundant to at least one other mechanism of complement resistance. B. burgdorferi appears to synthesize additional substances that protect against complement, such as a putative slime layer (Kraiczy et al., 2000) and a CD59-like protein that inhibits MAC formation (Pausa et al., 2003). Moreover Lyme borreliosis spirochetes are well known to express proteins during mammalian infection than are not produced during laboratory cultivation, so it is quite likely that bacterial factors not yet identified protect borreliae from complement in vivo. Supporting those hypotheses are the isolation of Lyme borreliae that are infectious for humans and other mammals, yet are unable to bind factor H in vitro (Alitalo et al., 2001; Kraiczy et al., 2001b; McDowell et al., 2003; Wallich et al., 2005).

B. burgdorferi may benefit from other functions of factor H. Eukaryotic cells bind factor H to their surfaces through several different specific and non-specific receptors (Avery and Gordon, 1993; DiScipio et al., 1998; Malhotra et al., 1999; Zipfel et al., 2002; Vaziri-Sani et al., 2005). Borrelial binding to factor H may therefore serve as a bridge to facilitate adherence to host cells and tissues (Hammerschmidt et al., 2007).

In addition, the studies of Woodman et al. (2007) indicated that B. burgdorferi do not coat themselves with detectable levels of host factor H during transmission from infected mice to feeding larval ticks. Those results suggest that Erp proteins and other CRASPs may bind host components other than factor H, which preclude CRASP-factor H binding (see below, and Hovis et al., 2006; McDowell et al., 2006).

Humans produce an additional serum protein, factor H-like protein 1 (FHL-1), from the same gene as factor H using an alternative mRNA splice site (Misasi et al., 1989; Zipfel et al., 2002). FHL-1 consists of the first 7 SCRs of factor H, plus a unique 4-amino-acid carboxy terminus. Since FHL-1 lacks the factor H SCR-20, Erp proteins do not bind FHL-1, although BbCRASPs-1 and -2 do bind (Hellwage et al., 2001; Kraiczy et al., 2001a, 2002a, 2002b, 2003, 2004b; Wallich et al., 2005; Hartmann et al., 2006). FHL-1 plays roles in both complement regulation and cell adhesion (Misasi et al., 1989; Hellwage et al., 1997; Friese et al., 1999; Zipfel and Skerka, 1999; Zipfel et al., 2002). However, mice and other rodents do not appear to produce FHL-1 (Stevenson et al., 2002; Zipfel et al., 2002), so while the ability of Lyme borreliae to bind FHL-1 might have consequences for human disease, that characteristic probably does not contribute to infection of other vertebrates or to the persistence of these spirochetes in nature.

Erp binding of host factor H-related proteins

Vertebrates produce several additional serum proteins known as factor H-related proteins (FHRs), with humans and mice each containing 5 distinct FHR-encoding genes (Zipfel et al., 2002; Hellwage et al., 2006). FHRs are smaller in size than is factor H, being comprised of between 4 and 9 SCRs (Zipfel et al., 2002). Some FHRs bear significant sequence similarities to factor H: for example, SCRs 3, 4, and 5 of human FHR-1 share 100, 100, and 97% identities to human factor H SCRs 18, 19, and 20, respectively (Zipfel et al., 2002). As might be expected from the high degree of similarities between the carboxy-terminal SCRs of factor H and FHR-1, ErpA, ErpC, and ErpP can each bind human FHR-1 (Haupt et al., 2007). Presumably, FHRs are among the unidentified serum proteins that Hovis et al. (2006) showed to bind ErpA and ErpP. The functions of FHR proteins are poorly understood. Some appear to play roles in regulation of the alternative pathway of complement activation (Hellwage et al., 1999, 2002, 2006; McRae et al., 2005; Zipfel et al., 2007). FHRs are also components of a plasma lipoprotein particle of unknown function (Park and Wright, 1996, 2000). Thus, binding of FHRs to the borrelial outer surface via Erp proteins might help facilitate resistance to complement or have other, unknown consequences.

Erp binding of host laminin

During mammalian infection, Lyme borreliosis spirochetes are frequently found associated with their hosts’ extracellular matrices (De Koning et al., 1987; Häupl et al., 1993; Pachner et al., 1995). Several extracellular matrix (ECM) components have been previously identified as potential ligands for B. burgdorferi outer surface proteins, including fibronectin and decorin (Guo et al., 1995; Feng et al., 1998; Grab et al., 1998; Hagman et al., 1998; Probert and Johnson, 1998). Laminins are a family of related glycoproteins that constitute major components of vertebrate basement membranes (Colognato and Yurchenco, 2000). Until recently, there had not been any studies on the potential for interactions between that important ECM component and B. burgdorferi.

Recent studies by our laboratory and others determined that the pathogenic spirochete Leptospira interrogans produces a family of outer surface lipoproteins with varying abilities to bind both factor H and laminin (our unpublished results and Barbosa et al., 2006; Verma et al., 2006). There are no genetic relationships between those leptospiral proteins and borrelial Erp proteins. However, factor H and laminin share affinities for the synthetic molecule heparin as well as for heparan sulfate and other negatively-charged glycosaminoglycans that are natural components of vertebrate cell surfaces. Most Erp proteins are predicted to have net negative charges, with acidic pI values. As examples, the mature ErpA protein contains 12% glutamate, 6% aspartate, and 14% lysine and has a predicted pI=5.1, while ErpX contains 18% glutamate, 9% aspartate, and 19% lysine residues and has a predicted pI=4.9. Those characteristics, plus the known affinities of some Erp proteins for the heparin-binding domain of factor H, led us to evaluate the abilities of Erp proteins to bind laminin.

Ligand affinity blot analyses of recombinant proteins of B. burgdorferi strain B31 revealed that ErpX bound laminin, although no other Erp protein of that strain exhibited affinity for laminin (Fig. 1) (our unpublished results). The erp26 gene of B. burgdorferi strain N40 is the known gene most closely related to erpX (Fig. 1), however, recombinant Erp26 protein did not detectably bind laminin (our unpublished results). To date, we have produced several mutant recombinant ErpX proteins, including one that lacks the amino-terminal 30 amino acids and the carboxy-terminal 31 amino acids, but all still bind laminin (our unpublished results). Further studies are ongoing in our laboratory to define the residues responsible for laminin binding by ErpX, discern the mechanism behind those interactions, and evaluate the importance of Erp-laminin binding on B. burgdorferi infection processes.

Conclusions and future directions

All Lyme borreliosis spirochetes naturally contain numerous different cp32 elements, each of which carries an erp locus. The ubiquity of cp32s is readily explained by the hypothesis of their being bacteriophage genomes: Bacteriophage particles can easily transmit DNA horizontally and result in bacteria carrying multiple compatible prophages, while bacteria that lose a cp32 would be rapidly re-infected by phages produced by neighboring spirochetes. Until recently, the presence of an erp locus on each cp32 has been much more difficult to explain. The erp locus is outside the apparent operon(s) that encode(s) probable borreliaphage structural and cell lysis proteins (Casjens et al., 2000; Damman et al., 2000; Zhang and Marconi, 2005). The relapsing fever spirochete B. hermsii also naturally carries numerous cp32 elements, but none of them contains an erp locus (Stevenson et al., 2000). Those data suggest that Erp proteins are not essential for cp32 maintenance within the bacterium or for bacteriophage-specific functions. The discoveries that some Erp proteins can bind host factor H or laminin, and may thereby protect the bacterium from complement-mediated killing or enhance host colonization, point toward functions for Erp proteins that do not directly affect the encoding cp32. It appears that cp32 elements encode Erp proteins to perform functions that benefit their bacterial hosts, and, by enhancing bacterial survival, cp32s also increase their own probabilities of thriving.

The recent discoveries of functions for Erp outer surface proteins raise many new questions. Do the factor H-binding and laminin-binding Erp proteins perform additional functions for the spirochete? Do the other Erp proteins also have functions, and what are they? Do sequence variations among Erp proteins of different bacterial strains affect the affinities of those proteins for their host ligands? Could Erp protein variations affect infectious abilities of the different borreliae? Answering those questions will provide important information on the molecular mechanisms by which Lyme borreliosis spirochetes infect and cause disease in humans and other vertebrate hosts

Acknowledgements

Research on Erp proteins by our laboratory is funded by US National Institutes of Health grant R01-AI44245. We thank our many colleagues around the world for their helpful scientific discussions and debates.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akins DR, Porcella SF, Popova TG, Shevchenko D, Baker SI, Li M, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homologue. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;18:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins DR, Caimano MJ, Yang X, Cerna F, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. Molecular and evolutionary analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi 297 circular plasmid-encoded lipoproteins with OspE- and OspF-like leader peptides. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:1526–1532. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1526-1532.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo A, Meri T, Rämö L, Jokiranta TS, Heikkilä T, Seppälä IJT, Oksi J, Viljanen M, Meri S. Complement evasion by Borrelia burgdorferi: serum-resistant strains promote C3b inactivation. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:3685–3691. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3685-3691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo A, Meri T, Lankinen H, Seppälä I, Lahdenne P, Hefty PS, Akins D, Meri S. Complement inhibitor factor H binding to Lyme disease spirochetes is mediated by inducible expression of multiple plasmid-encoded outer surface protein E paralogs. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3847–3853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo A, Meri T, Chen T, Lankinen H, Cheng Z-Z, Jokiranta TS, Seppälä IJT, Lahdenne P, Hefty PS, Akins DR, Meri S. Lysine-dependent multipoint binding of the Borrelia burgdorferi virulence factor outer surface protein E to the C terminus of factor H. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6195–6201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M, Perkins SJ. Folded-back solution structure of monomeric factor H of human complement by synchrotron X-ray and neutron scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation and constrained molecular modeling. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;309:1117–1138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery VM, Gordon DL. Characterization of factor H binding to polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Immunol. 1993;151:5545–5553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb K, McAlister JD, Miller JC, Stevenson B. Molecular characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi erp promoter/operator elements. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2745–2756. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2745-2756.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb K, Bykowski T, Riley SP, Miller MC, DeMoll E, Stevenson B. Borrelia burgdorferi EbfC, a novel, chromosomally-encoded protein, binds specific DNA sequences adjacent to erp loci on the spirochete’s resident cp32 prophages. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:4331–4339. doi: 10.1128/JB.00005-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AS, Abreu PAE, Neves FO, Atzingen MV, Watanabe MM, Vieira ML, Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimentao ALTO. A newly identified leptospiral adhesin mediates attachment to laminin. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6356–6364. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00460-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW. Infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi relative to route of inoculation and genotype in laboratory mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1991;163:419–420. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brade V, Kleber I, Acker G. Differences of two Borrelia burgdorferi strains in complement activation and serum resistance. Immunobiology. 1992;185:453–465. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitner-Ruddock S, Würzner R, Schulze J, Brade V. Heterogeneity in the complement-dependent bacteriolysis within the species of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1997;185:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s004300050038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CS, Vuppala SR, Jett AM, Alitalo A, Meri S, Akins DR. Complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 imparts resistance to human serum in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3299–3308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caimano MJ, Yang X, Popova TG, Clawson ML, Akins DR, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. Molecular and evolutionary characterization of the cp32/18 family of supercoiled plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi 297. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:1574–1586. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1574-1586.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa PA, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids present in Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, Rosa P, Lathigra R, Sutton G, Peterson J, Dodson RJ, Haft D, Hickey E, Gwinn M, White O, Fraser C. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs of an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens SR, Huang WM, Gilcrease EB, Qiu W, McCaig WD, Luft BJ, Schutzer SE, Fraser CM. Comparative genomics of Borrelia burgdorferi. In: Cabello FC, Hulinska D, Godfrey HP, editors. Molecular Biology of Spirochetes. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2006. pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cassatt DR, Patel NK, Ulbrandt ND, Hanson MS. DbpA, but not OspA, is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during spirochetemia and is a target for protective antibodies. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:5379–5387. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5379-5387.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ZZ, Hellwage J, Seeberger H, Zipfel PF, Meri S, Jokiranta TS. Comparison of surface recognition and C3b binding properties of mouse and human complement factor H. Mol. Immunol. 2006;43:972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H, Yurchenco PD. Form and function: the laminin family of heterotrimers. Dev. Dynamics. 2000;218:213–234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200006)218:2<213::AID-DVDY1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damman CJ, Eggers CH, Samuels DS, Oliver DB. Characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi BlyA and BlyB proteins: a prophage-encoded holin-like system. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6791–6797. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6791-6797.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Barthold SW, Stocker Giles S, Montgomery RR, Telford SR, Fikrig E. Temporal pattern of Borrelia burgdorferi p21 expression in ticks and the mammalian host. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:987–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI119264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning J, Bosma RB, Hoogkamp-Korstanje JA. Demonstration of spirochaetes in patients with Lyme disease with a modified silver stain. J. Med. Microbiol. 1987;23:261–267. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-3-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiScipio RG, Daffern PJ, Schraufstätter IU, Sriramarao P. Human polymorphonuclear leukocytes adhere to complement factor H through an interaction that involves αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18) J. Immunol. 1998;160:4057–4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers CH, Samuels DS. Molecular evidence for a new bacteriophage of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:7308–7313. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7308-7313.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers CH, Kimmel BJ, Bono JL, Elias AF, Rosa P, Samuels DS. Transduction by ØBB-1, a bacteriophage of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:4771–4778. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4771-4778.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers CH, Caimano MJ, Radolf JD. Analysis of promoter elements involved in the transcription initiation of RpoS-dependent Borrelia burgdorferi genes. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:7390–7402. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7390-7402.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers CH, Caimano MJ, Radolf JD. Sigma factor selectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi: RpoS recognition of the ospE/ospF/elp promoters is dependent on the sequence of the –10 region. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:1859–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Babb K, Carroll JA, Lindstrom N, Fischer ER, Miller JC, Gilmore RD, Jr, Mbow ML, Stevenson B. Surface exposure and protease insensitivity of Borrelia burgdorferi Erp (OspEF-related) lipoproteins. Microbiology. 2001;147:821–830. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hage N, Stevenson B. Simultaneous coexpression of Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins occurs through a specific, erp locus-directed regulatory mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:4536–4543. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4536-4543.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Hodzic E, Stevenson B, Barthold SW. Humoral immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi N40 decorin binding proteins during infection of laboratory mice. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:2827–2835. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2827-2835.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum KA, Dodson R, Hickey EK, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J-F, Fleischmann RD, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage AR, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams MD, Gocayne J, Weidmann J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fujii C, Cotton MD, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith HO, Venter JC. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Hellwage J, Jokiranta TS, Meri S, Peter HH, Eibel H, Zipfel PF. FHL-1/reconectin and factor H: two human complement regulators which are encoded by the same gene are differently expressed and regulated. Mol. Immunol. 1999;36:809–818. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore RD, Jr, Mbow ML, Stevenson B. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression during life cycle phases of the tick vector Ixodes scapularis. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:799–808. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grab DJ, Givens C, Kennedy R. Fibronectin-binding activity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1407:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo BP, Norris SJ, Rosenberg LC, Höök M. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi to the proteoglycan decorin. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:3467–3472. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3467-3472.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman KE, Lahdenne P, Popova TG, Porcella SF, Akins DR, Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Decorin-binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is encoded within a two-gene operon and is protective in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:2674–2683. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2674-2683.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt S, Agarwal V, Kunert A, Haelbich H, Skerka C, Zipfel PF. The host immune regulator factor H interacts via two contact sites with the PspC protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mediates adhesion to host epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5848–5858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann K, Corvey C, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Karas M, Brade V, Miller JC, Stevenson B, Wallich R, Zipfel PF, Kraiczy P. Functional characterization of BbCRASP-2, a distinct outer membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi that binds host complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1220–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häupl T, Hahn G, Rittig M, Krause A, Schoerner C, Schönherr U, Kalden JR, Burmester GR. Persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi in ligamentous tissue from a patient with chronic Lyme borreliosis. Arthritis. Rheum. 1993;36:1621–1626. doi: 10.1002/art.1780361118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt K, Wallich R, Kraiczy P, Brade V, Skerka C, Zipfel PF. Binding of human FHR-1 to serum resistant Borrelia burgdorferi is mediated by borrelial complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:124–133. doi: 10.1086/518509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Caimano MJ, Wikel SK, Radolf JD, Akins DR. Regulation of OspE-related, OspF-related, and Elp lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi strain 297 by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:3618–3627. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3618-3627.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Caimano MJ, Wikel SK, Akins DR. Changes in the temporal and spatial patterns of outer surface lipoprotein expression generate population heterogeneity and antigenic diversity in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:3468–3478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3468-3478.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwage J, Kühn S, Zipfel PF. The human complement regulatory factor-H-like protein 1, which represents a truncated form of factor H, displays cell-attachment activity. Biochem. J. 1997;326:321–327. doi: 10.1042/bj3260321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwage J, Jokiranta TS, Koistinen V, Vaarala O, Meri S, Zipfel PF. Functional properties of complement factor H-related proteins FHR-3 and FHR-4: binding to the C3d region of C3b and differential regulation by heparin. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwage J, Meri T, Heikkilä T, Alitalo A, Panelius J, Lahdenne P, Seppälä IJT, Meri S. The complement regulatory factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8427–8435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwage J, Jokiranta TS, Friese MA, Wolk TU, Kampen E, Zipfel PF, Meri S. Complement C3b/C3d and cell surface polyanions are recognized by overlapping binding sites on the most carboxy-terminal domain of complement factor H. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6935–6944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwage J, Eberle F, Babuke T, Seeberger H, Richter H, Kunert A, Hartl A, Zipfel PF, Jokiranta TS, Jozsi M. Two factor H-related proteins from the mouse: expression, analysis and functional characterization. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:883–893. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0153-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovis KM, Tran E, Sundy CM, Buckles E, McDowell JV, Marconi RT. Selective binding of Borrelia burgdorfer OspE paralogs to factor H and serum proteins from diverse animals: possible expansion of the role of OspE in Lyme disease pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:1967–1972. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1967-1972.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R, Kalu O, Purser J, Norris S, Stevenson B, Schwartz I. Linear and circular plasmid content in Borrelia burgdorferi clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3699–3706. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3699-3706.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokiranta TS, Cheng ZZ, Seeberger H, Józsi M, Heinen S, Noris M, Remuzzi G, Ormsby R, Gordon DL, Meri S, Hellwage J, Zipfel PF. Binding of complemet factor H to endothelial cells is mediated by the carboxy-terminal glycosaminoglycan binding site. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61205-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jószi M, Oppermann M, Lambris JD, Zipfel PF. The C-terminus of complement factor H is essential for host cell protection. Mol. Immunol. 2007;44:2697–2706. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochi SK, Johnson RC, Dalmasso AP. Complement-mediated killing of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi: role of antibody in formation of an effective membrane attack complex. J. Immunol. 1991;146:3964–3970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hunfeld K-P, Breiner-Ruddock S, Würzner R, Acker G, Brade V. Comparison of two laboratory methods for the determination of serum resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi isolates. Immunobiology. 2000;201:406–419. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(00)80094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Brade V, Zipfel PF. Further characterization of complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2001a;69:7800–7809. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7800-7809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL-1/reconectin and factor H. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001b;31:1674–1684. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1674::aid-immu1674>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Zipfel PF, Brade V. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi: insufficient killing of the pathogens by complement and antibody. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2002a;291 Suppl. 33:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s1438-4221(02)80027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Brade V. Complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi: a new protein family involved in complement resistance. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002b;114:568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi: mapping of a complement inhibitor factor H-binding site of BbCRASP-3, a novel member of the Erp protein family. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:697–707. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hartmann K, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R, Stevenson B. Immunological characterization of the complement regulator factor H-binding CRASP and Erp proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004a;293 Suppl. 37:152–157. doi: 10.1016/s1433-1128(04)80029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Becker H, Kirschfink M, Simon MM, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R. Complement resistance of Borrelia burgdorferi correlates with the expression of BbCRASP-1, a novel linear plasmid-encoded surface protein that interacts with human factor H and FHL-1 and is unrelated to Erp proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2004b;279:2421–2429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Rossmann E, Brade V, Simon MM, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Wallich R. Binding of human complement regulators FHL-1 and factor H to CRASP-1 orthologs of Borrelia burgdorferi. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2006;118:669–676. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtenbach K, Sewell H-S, Ogden NH, Randolph SE, Nuttall PA. Serum complement sensitivity as a key factor in Lyme disease ecology. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1248–1251. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1248-1251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtenbach K, DeMichelis S, Etti S, Schäfer SM, Sewell H-S, Brade V, Kraiczy P. Host association of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato – the key role of host complement. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:74–79. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TT, Nguyen T-PK, Montgomery RR, Kantor FS, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Outer surface proteins E and F of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 1994;62:290–298. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.290-298.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang FT, Nelson FK, Fikrig E. Molecular adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine host. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:275–280. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Ward M, Sim RB, Bird MI. Identification of human complement factor H as a ligand for L-selectin. Biochem. J. 1999;341:61–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi RT, Sung SY, Hughes CAN, Carlyon JA. Molecular and evolutionary analyses of a variable series of genes in Borrelia burgdorferi that are related to ospE and ospF, constitute a gene family, and share a common upstream homology box. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5615–5626. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5615-5626.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Sung SY, Price G, Marconi RT. Demonstration of the genetic stability and temporal expression of select members of the Lyme disease spirochete OspF protein family during infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4831–4838. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4831-4838.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Wolfgang J, Tran E, Metts MS, Hamilton D, Marconi RT. Comprehensive analysis of the factor H binding capabilities of Borrelia species associated with Lyme disease: delineation of two distinct classes of factor H binding proteins. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3597–3602. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3597-3602.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Wolfgang J, Senty L, Sundy CM, Noto MJ, Marconi RT. Demonstration of the involvement of outer surface protein E coiled coil structural domains and higher order structural elements in the binding of infection-induced antibody and the complement-regulatory protein, factor H. J. Immunol. 2004;173:7471–7480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Hovis KM, Zhang H, Tran E, Lankford J, Marconi RT. Evidence that BBA68 protein (BbCRASP-1) of the Lyme disease spirochetes does not contribute to factor H-mediated immune evasion in humans and other animals. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:3030–3034. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.3030-3034.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae JL, Duthy TG, Griggs KM, Ormsby RJ, Cowan PJ, Cromer BA, McKinstry WJ, Parker MW, Murphy BF, Gordon DL. Human factor H-related protein 5 has cofactor activity, inhibits C3 convertase activity, binds heparin and C-reactive protein, and associates with lipoprotein. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6250–6256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metts MS, McDowell JV, Theisen M, Hansen PR, Marconi RT. Analysis of the OspE determinants involved in binding of factor H and OspE-targeting antibodies elicited during Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3587–3596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3587-3596.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Bono JL, Babb K, El-Hage N, Casjens S, Stevenson B. A second allele of eppA in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is located on the previously undetected circular plasmid cp9-2. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6254–6258. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6254-6258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, von Lackum K, Babb K, McAlister JD, Stevenson B. Temporal analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi Erp protein expression throughout the mammal-tick infectious cycle. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:6943–6952. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6943-6952.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Narayan K, Stevenson B, Pachner AR. Expression of Borrelia burgdorferi erp genes during infection of non-human primates. Microb. Pathog. 2005;39:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Stevenson B. Borrelia burgdorferi erp genes are expressed at different levels within tissues of chronically infected mammalian hosts. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;296 Suppl. 1:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, von Lackum K, Woodman ME, Stevenson B. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression during mammalian infection using transcriptional fusions that produce green fluorescent protein. Microb. Pathog. 2006;41:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misasi R, Huemer HP, Schwaeble W, Solder E, Larcher C, Dierich MP. Human complement factor H: an additional gene product of 43 kDa isolated from human plasma shows cofactor activity for the cleavage of the third component of complement. Eur. J. Immunol. 1989;19:1765–1768. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann M, Manuelian T, Józsi M, Brandt E, Jokiranta TS, Heinen S, Meri S, Skerka C, Götze O, Zipfel PF. The C-terminus of complement regulator factor H mediates target recognition: evidence for a compact conformation of the native protein. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2006;144:342–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachner AR, Basta J, Delaney E, Hulinska D. Localization of Borrelia burgdorferi in murine Lyme borreliosis by electron microscopy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1995;52:128–133. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CT, Wright SD. Plasma lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is found associated with a particle containing apolipoprotein A-I, phospholipid, and factor H-related proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18054–18060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CT, Wright SD. Fibrinogen is a component of a novel lipoprotein particle: factor H-related protein (FHRP)-associated lipoprotein particle (FALP) Blood. 2000;95:198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patarakul K, Cole MF, Hughes CAN. Complement resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi strain 297: outer membrane proteins prevent MAC formation at lysis susceptible sites. Microb. Pathog. 1999;27:25–41. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pausa M, Pellis V, Cinco M, Giulianini PG, Presani G, Perticarari S, Murgia R, Tedesco F. Serum-resistant strains of Borrelia burgdorferi evade complement-mediated killing by expressing a CD59-like complement inhibitory molecule. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3214–3222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins SJ, Goodship TH. Molecular modelling of the C-terminal domains of factor H of human complement: a correlation between haemolytic uraemic syndrome and a predicted heparin binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;316:217–224. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcella SF, Popova TG, Akins DR, Li M, Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Borrelia burgdorferi supercoiled plasmids encode multi-copy tandem open reading frames and a lipoprotein gene family. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:3293–3307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3293-3307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert WS, Johnson BJB. Identification of a 47 kDA fibronectin-binding protein expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi isolate B31. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;30:1003–1015. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodinger WM, Hellwage J, Spruth M, Deirich MP, Zipfel PF. The C-terminus of factor H: monoclonal antibodies inhibit heparin binding and identify epitopes common to factor H and factor H-related proteins. Biochem. J. 1998;331:41–47. doi: 10.1042/bj3310041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson WJ, Garon CF, Schwan TG. Borrelia burgdorferi contains repeated DNA sequences that are species specific and plasmid associated. Infect. Immun. 1990;58:847–853. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.847-853.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1639–1647. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14798-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Schwan TG, Rosa PA. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:4535–4539. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4535-4539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa PA. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Casjens S, van Vugt R, Porcella SF, Tilly K, Bono JL, Rosa P. Characterization of cp18, a naturally truncated member of the cp32 family of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:4285–4291. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4285-4291.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Bono JL, Schwan TG, Rosa P. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect. Immun. 1998a;66:2648–2654. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2648-2654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Casjens S, Rosa P. Evidence of past recombination events among the genes encoding the Erp antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology. 1998b;144:1869–1879. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Porcella SF, Oie KL, Fitzpatrick CA, Raffel SJ, Lubke L, Schrumpf ME, Schwan TG. The relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii contains multiple, antigen-encoding circular plasmids that are homologous to the cp32 plasmids of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:3900–3908. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3900-3908.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Zückert WR, Akins DR. Repetition, conservation, and variation: the multiple cp32 plasmids of Borrelia species. In: Saier MH, García-Lara J, editors. The Spirochetes: Molecular and Cellular Biology. Oxford: Horizon Press; 2001. pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, El-Hage N, Hines MA, Miller JC, Babb K. Differential binding of host complement inhibitor factor H by Borrelia burgdorferi Erp surface proteins: a possible mechanism underlying the expansive host range of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:491–497. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.491-497.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Miller JC. Intra- and interbacterial genetic exchange of Lyme disease spirochete erp genes generates sequence identity amidst diversity. J. Mol. Evol. 2003;57:309–324. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B, Bykowski T, Cooley AE, Babb K, Miller JC, Woodman ME, von Lackum K, Riley SP. The Lyme disease spirochete Erp lipoprotein family: structure, function and regulation of expression. In: Cabello FC, Godfrey HP, Hulinska D, editors. Molecular Biology of Spirochetes. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2006. pp. 354–372. [Google Scholar]

- Suk K, Das S, Sun W, Jwang B, Barthold SW, Flavell RA, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi genes selectively expressed in the infected host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4269–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*, phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam AP, Oei A, Jaspars R, Fijen C, Wilske B, Spanjaard L, Dankert J. Complement-mediated serum sensitivity among spirochetes that cause Lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:1228–1236. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1228-1236.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri-Sani F, Hellwage J, Zipfel PF, Sjöholm AG, Iancu R, Karpman D. Factor H binds to washed human platelets. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2005;3:154–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A, Hellwage J, Artiushin S, Zipfel PF, Kraiczy P, Timoney JF, Stevenson B. LfhA, a novel factor H-binding protein of Leptospira interrogans. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:2659–2666. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2659-2666.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallich R, Pattathu J, Kitiratschky V, Brenner C, Zipfel PF, Brade V, Simon MM, Kraiczy P. Identification and functional characterization of complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 of the Lyme disease spirochetes Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:2351–2359. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2351-2359.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman ME, Cooley AE, Miller JC, Lazarus JJ, Tucker K, Bykowski T, Botto M, Hellwage J, Wooten RM, Stevenson B. Borrelia burgdorferi binding of host complement regulator factor H is not required for efficient mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:3131–3139. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01923-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormser GP. Hematogenous dissemination in early Lyme disease. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2006;118:634–637. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0688-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Marconi RT. Demonstration of cotranscription and 1-methyl-3-nitroso-nitroguanidine induction of a 30-gene operon of Borrelia burgdorferi: evidence that the 32-kilobase circular plasmids are prophages. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7985–7995. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.7985-7995.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Skerka C. FHL-1/reconectin: a human complement and immune regulator with cell-adhesive function. Immunol. Today. 1999;20:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Skerka C, Hellwage J, Jokiranta ST, Meri S, Brade V, Kraiczy P, Noris M, Remuzzi G. Factor H family proteins: on complement, microbes and human diseases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:971–978. doi: 10.1042/bst0300971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PF, Edey M, Heinen S, Jozzi M, Richter H, Misselwitz J, Hoppe B, Routledge D, Strain L, Hughes AE, Goodship JA, Licht C, Goodship THJ, Skerka C. Deletion of complement factor H-related genes CFHR1 and CFHR3 is associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR, Meyer J. Circular and linear plasmids of Lyme disease spirochetes have extensive homology: characterization of a repeated DNA element. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:2287–2298. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2287-2298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]