Abstract

Regulation of mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) permeability has dual importance: in normal metabolite and energy exchange between mitochondria and cytoplasm and thus in control of respiration, and in apoptosis by release of apoptogenic factors into the cytosol. However, the mechanism of this regulation, dependent on the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), the major channel of MOM, remains controversial. A long-standing puzzle is that in permeabilized cells, adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) is less accessible to cytosolic ADP than in isolated mitochondria. We solve this puzzle by finding a missing player in the regulation of MOM permeability: the cytoskeletal protein tubulin. We show that nanomolar concentrations of dimeric tubulin induce voltage-sensitive reversible closure of VDAC reconstituted into planar phospholipid membranes. Tubulin strikingly increases VDAC voltage sensitivity and at physiological salt conditions could induce VDAC closure at <10 mV transmembrane potentials. Experiments with isolated mitochondria confirm these findings. Tubulin added to isolated mitochondria decreases ADP availability to ANT, partially restoring the low MOM permeability (high apparent Km for ADP) found in permeabilized cells. Our findings suggest a previously unknown mechanism of regulation of mitochondrial energetics, governed by VDAC and tubulin at the mitochondria–cytosol interface. This tubulin–VDAC interaction requires tubulin anionic C-terminal tail (CTT) peptides. The significance of this interaction may be reflected in the evolutionary conservation of length and anionic charge in CTT throughout eukaryotes, despite wide changes in the exact sequence. Additionally, tubulins that have lost significant length or anionic character are only found in cells that do not have mitochondria.

Keywords: evolution, microtubules, oxidative phosphorylation, VDAC, tubulin C-terminal

Oxidative phosphorylation requires transport of metabolites, including cytosolic ADP, ATP, and inorganic phosphate, across both mitochondrial membranes for F1F0-ATPase to generate ATP in the matrix. Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC, also called mitochondrial porin) is the most abundant protein in mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) and is known to be primarily responsible for ATP/ADP flux across the outer membrane (1, 2). Until recently, VDAC was generally viewed as a part of the pathway for release of cytochrome c and other apoptogenic factors from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol at the early stage of apoptosis. The recent genetic studies undermined this view (3) but still left open a lot of questions concerning the role of VDAC in MOM permeabilization in apoptosis (4–6). A conserved property of VDACs in vitro is the ability to adopt a unique fully open state and multiple states with significantly smaller conductance (7). It was demonstrated that the latter, so called “closed states” are impermeable to ATP but still permeable to small ions (8), including Ca2+ (9).

In isolated mitochondria, respiration is characterized by an apparent Km for exogenous ADP that is ≈10-fold lower than in permeabilized cells with oxidative metabolism (10, 11). The discrepancy is most likely caused by a lower permeability of the MOM (and hence VDAC) for ADP in the permeabilized cells and may be the result of the interaction of mitochondria with some cytoskeletal protein(s). Such a conjecture is supported by the action of mild trypsin treatment of permeabilized cells, which causes decrease in apparent Km for ADP accompanied by mitochondrial rearrangement, implicating the existence of a protein factor(s) associated with the cytoskeleton (10). The decreased value of apparent Km for ADP after mild proteolytic treatment was similar to Km in isolated mitochondria and purified preparations of adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) (10), thus showing that the kinetic values of ANT are similar in all preparations. Therefore, high values of apparent Km for ADP in permeabilized cells are related to decreased permeability of MOM, possibly because of interaction with cytosolic proteins.

Tubulin, the subunit of microtubules, is a plausible candidate because this cytoskeletal protein is known to interact with mitochondria (12, 13). In addition to mitochondrial membranes, tubulin has been shown to interact with proteins associated with other membranes (14, 15). Tubulin is a heterodimer, composed of similar 50-kDa globular α and β subunits. Each subunit possess a negatively charged, extended C-terminal tail (CTT) that represents ≈3% of the subunit mass and ≈40% of the subunit charge (16, 17). Tubulin shows saturable, high-affinity binding to intact mitochondria (12) and hence to MOM, although the region of tubulin responsible for binding has not yet been identified. Immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated a specific association of VDAC with tubulin (13), which indicates that VDAC could be a receptor for tubulin binding to MOM. Exploring this possibility, we studied the functional interaction between VDAC and tubulin to show that nanomolar concentrations of dimeric* tubulin induce highly voltage-sensitive reversible closure of VDAC reconstituted into planar phospholipid membranes.

Results and Discussion

Tubulin Induces Reversible Blockage of VDAC Reconstituted into Planar Phospholipid Membranes.

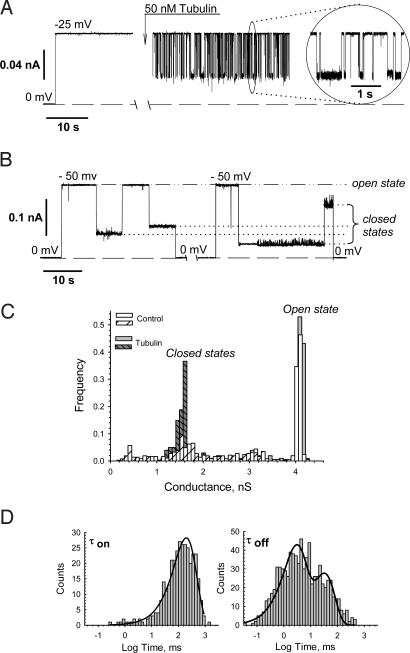

A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 1A, where addition of 50 nM tubulin to the cis side (the side of VDAC addition) of the membrane induced fast reversible blockage of VDAC conductance, markedly different from VDAC gating induced by voltage alone (Fig. 1B). Although voltage-induced and tubulin-induced VDAC closures are both voltage-dependent, the properties of these 2 processes are very different. First, tubulin greatly enhances VDAC voltage sensitivity, inducing channel closure at potentials as low as 10 mV. Without tubulin, VDAC remains open at the conditions of Fig. 1A for up to 1 h. Typical VDAC voltage gating without tubulin is shown in Fig. 1B, where application of 50 mV switches the channel from the open to low conducting, “closed” states. Once closed, VDAC will typically stay closed until the voltage is relaxed to 0 mV. Second, tubulin induces a single closed state of VDAC (0.4 of open-state conductance), seen in the distribution of conductances in Fig. 1C. In contrast, the control “normal” voltage gating exhibits a wide variety of closed states (Fig. 1 B and C). Open-state conductance is unaltered by tubulin addition.

Fig. 1.

Tubulin at nanomolar concentrations induces reversible partial blockage of VDAC. (A) Representative current record through a single channel before and after addition of 50 nM tubulin to the cis side at −25 mV applied voltage. Addition of tubulin induces time-resolved rapid events of partial channel blockages to a single well-defined conductance level, shown in the Inset at a finer scale. Here and elsewhere, dashed lines indicate zero-current level; current records were filtered by using averaging times of 10 ms (except for 1 ms in Inset). (B) Typical VDAC voltage gating in tubulin-free solution under periodically applied −50 mV voltage impulses. Under applied voltage, channel conductance moves from a single high-conducting open state to various low-conducting closed states. Relaxing the voltage to 0 mV reopens the channel. The dashed-and-dotted line indicates the conductance of the channel in its open state and dotted lines in its closed states. (C) Tubulin induces a single well-resolved closed state of VDAC, whereas in control voltage-induced gating a wide variety of closed states is observed. The distribution of conductances in control was collected from a series of −50 mV impulses of 30 s duration interrupted by 70 s periods of zero applied voltage to restore the open state. (D) Statistical analysis of the tubulin-induced closures of VDAC performed by logarithmic exponential fitting of the open times (τon) and closed times (τoff). It is seen that open time is described by single exponent with characteristic time τon = 198.7 ± 3.5 ms. Closed-time histogram could be fitted by at least 2 exponents with characteristic times of τoff(1) = 2.4 ± 0.1 ms and τoff(2) = 30.4 ± 5.7 ms. The time histograms were collected from the current traces presented in A. Bilayer membranes were formed from the mixture of asolectin and cholesterol (10:1 wt/wt). VDAC was isolated from rat liver mitochondria. The medium consisted of 1 M KCl buffered with 5 mM Hepes at pH 7.4.

This answers a long-standing quandary: how could VDAC voltage gating observed in planar lipid bilayer systems at relatively high potentials (>30 mV) be relevant to the situation in vivo, and in isolated mitochondria, where the most probable values of potential difference across MOM were estimated to be smaller than 10–20 mV (18)?

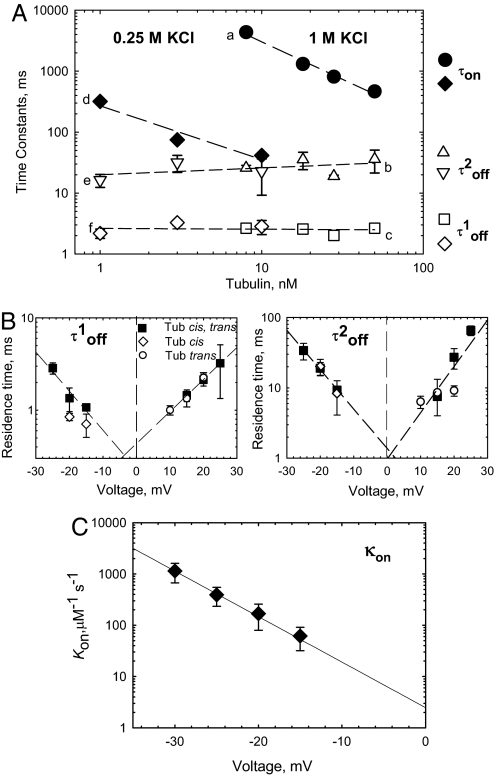

The binding parameters for tubulin-induced closure depend strongly on tubulin concentration, electrolyte concentration, and applied voltage (Fig. 2). The distributions of open time (τopen) are satisfactorily described by single exponential fitting (Fig. 1D Left, continuous lines). As expected for simple bimolecular binding causing VDAC closure, τopen decreases as tubulin concentration increases (Fig. 2A a and d). Open time decreases by 1 order of magnitude as tubulin concentration increases 10 times. Channel closed time, which is the residence time for the tubulin bound to VDAC pore, is independent of tubulin concentration, as expected for first-order dissociation of the tubulin–VDAC complex (Fig. 2A e, b, f, and c). Distributions of closed time require 2 exponentials for fitting (Fig. 1D Right, continuous line), indicating, most probably, that there are 2 forms of tubulin that differ in residence time. This could be the result of differential binding of the α- versus β-tubulin CTT. The β-CTT contains ≈40% more negative charge than α-CTT and may remain bound longer because of that. Further experiments will be required to resolve this point.

Fig. 2.

The binding parameters for tubulin-induced VDAC closure depend on tubulin concentration, electrolyte concentration, and applied voltage. (A) (a and d) VDAC open time between successive blockages, τon, linearly decreases with tubulin concentration and depends on salt concentration. The medium consisted of 1 M KCl (a, filled circles) and 0.25 M KCl (d, filled diamonds). Both components of tubulin residence (closed) time, τoff(1)and τoff(2), are independent of tubulin or salt concentration (b, c, e, and f, open symbols) and are equal to 2.8 ± 0.5 ms and 23.7 ± 6.3 ms, respectively. The applied voltage was −20 mV. (B) Voltage dependence of VDAC residence times, τoff(1) and τoff(2), in the presence of 50 nM tubulin in cis (open diamonds), trans (open circles), or both sides (filled squares) of the membrane. Residence time in extrapolation to 0 voltage does not depend on 1-side (cis or trans) or 2-side tubulin addition. (C) Voltage dependence of the on-rate, κon, with 50 nM tubulin added to the cis side. The line is an exponential fit to κon = κ0exp(nVF/RT) with n = 4.97. Each time value presents the characteristic time of 9 different log probability fitting procedures ± SE. The medium consisted of 1 M KCl (B and C) and buffered with 5 mM Hepes at pH 7.4. VDAC was isolated from N. crassa mitochondria. Bilayer membranes were formed from DPhPC.

The involvement of electrostatic interactions in VDAC–tubulin binding is indicated by the strong dependence of τopen on salt concentration (Fig. 2A). High-salt concentration screens charges on tubulin and VDAC, decreasing binding. The increased screening leads to a >100-fold rise in τopen when KCl was increased 4-fold but does not affect either component of τclosed (Fig. 2A).

With symmetrical tubulin addition, the closed time did not depend on the polarity of the applied voltage, at least within the measurement accuracy (Fig. 2B). After asymmetric addition, when tubulin was added from one side of the membrane only, the blockage events were observable only when potential on the side of tubulin addition was more negative than on the other side, with a strong exponential dependence of the on-rate on the applied voltage (Fig. 2C). Under these conditions, the closed time did not depend on the side of tubulin addition if the polarity of the applied voltage was reversed accordingly (Fig. 2B).

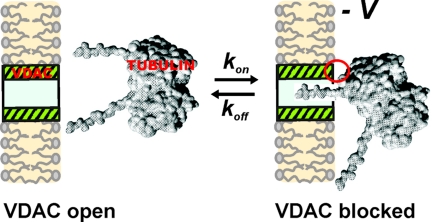

The tubulin dimer of 100-kDa molecular mass and approximate dimensions of 8 nm × 4.5 nm × 6.5 nm cannot permeate through the VDAC pore of 2.5- to 3.0-nm diameter. However, the CTT are long enough (17) to span the membrane channel and narrow enough to fit into the lumen of the channel, which permits us to suggest that the average time of tubulin-induced channel closure represents the average time of CTT residence in the channel lumen. Extrapolation of the on-rate and residence time dependencies to 0 voltage gives an estimate for the equilibrium constant of tubulin–VDAC binding as 0.5 and 2.5 nM−1 (for the 2 τclosed). These results allow us to suggest that tubulin-binding site(s) are equally accessible from both sides of the channel and that anionic CTT are mainly responsible for VDAC blockage (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Model of tubulin–VDAC interaction. One tubulin CTT partially blocks channel conductance by entering VDAC pore. This process is voltage-dependent and could be described by the 1st-order reaction of one-to-one binding of tubulin to VDAC. Some additional interaction between tubulin globular body and VDAC may be involved. The model of a tubulin dimer was redrawn from ref. 17.

Role of CTT in Tubulin–VDAC Interaction.

To test the CTT-dependent mechanism, we studied the effect of tubulin with truncated C termini, tubulin-S, on VDAC conductance. Comparison of VDAC current traces in the presence of tubulin-S (Fig. 3A) and intact tubulin (viz.“tubulin”) (Fig. 3C), obtained under the same experimental conditions, shows a striking difference. Tubulin-S did not induce reversible blockage typical for tubulin, but instead generated shorter current interruptions with τclosed <1 ms and rather broad distribution of conductances of the closed states [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1a]. An excess of current noise in the presence of tubulin-S indicates that the tubulin globular body interacts with VDAC even without CTT. However, these interactions most likely are of different nature than those with intact tubulin. Accordingly, experiments on multichannel membranes confirmed that tubulin-S does not affect VDAC voltage-gating parameters such as gating charge and the characteristic voltage at which half-channels are open and half-closed (Fig. S1b and Table S1). Results similar to tubulin-S (i.e., the absence of reversible channel blockage) were obtained with actin (Fig. S2), also an acidic protein but lacking CTT. This agrees with a previous report of actin interaction with VDAC from Neurospora crassa (19).

Fig. 3.

Tubulin interaction with VDAC requires the presence of C-terminal tails of tubulin. Tubulin (50 nM) with truncated CTT, tubulin-S (A), or a mixture of 10 μM 2 synthetic peptides of mammalian α- and β-brain tubulin CTT (B) does not induce channel blockage characteristic for intact tubulin (10 nM), with fast reversible blockage to 1 closed state (C). Representative current traces through single VDAC were obtained at ±25 mV of applied voltage in 1 M KCl solutions buffered with 5 mM Hepes at pH 7.4. Tubulin, tubulin-S, and CTT peptides were added to both sides of the membrane. Other experimental conditions were as in Fig. 2 B and C.

It was shown that a number of different synthetic and natural polyanions nonspecifically increase VDAC voltage gating (7). This raises a question about specificity of VDAC closure by tubulin, considering that CTT are highly negatively charged. To address this, we studied the effect of CTT synthetic peptides on VDAC properties. Two synthetic peptides with the sequences of mammalian α and β brain tubulin CTT did not induce detectable channel closure up to micromolar concentrations. In the experiment presented in Fig. 3B, a mixture of 2 synthetic peptides (10 μM each) corresponding in sequence to mammalian α and β brain tubulin CTT was added to both sides of the membrane, but the current traces through single channels were indistinguishable from control traces. This suggests that CTT peptides translocate through the channel too fast, in a <0.1 ms time scale, and do not block it in a time-resolved manner. Experiments on multichannel membranes confirmed that VDAC voltage-gating parameters were also not affected by CTT peptides (Fig. S3). Thus, the results with tubulin-S, actin, and CTT synthetic peptides support our model of tubulin CTT interaction with VDAC leading to the voltage-dependent channel closure.

When tubulin CTT penetrates into the VDAC lumen (Fig. 4), its negative charge changes channel ion selectivity. The residual conductance of the channel during tubulin block was cation-selective with the permeability ratio of PK/PCl = 2.4 ± 0.7 and reversal potential of (−14 ± 4) mV in 1.0 M cis/0.2 M trans gradient of KCl. This should be compared with the anion selectivity of VDAC open state, which is characterized by PK/PCl = 0.5 ± 0.02 and reversal potential of (12 ± 1) mV. The selectivity inversion further supports the proposed model where VDAC closure arises from interaction of negatively charged CTT with net positively charged channel interior (Fig. 4). A similar effect on VDAC selectivity was described when negatively charged phosphorothioate oligonucleotides blocked VDAC (20).

The effect of tubulin blockage of VDAC was confirmed with VDAC isolated from mitochondria from rat liver (see traces in Fig. 1A) and heart and from N. crassa (see traces in Fig. 3C), and with tubulin isolated from bovine and rat brain, which gave indistinguishable results. Tubulin isolated from Leishmania tarentolae and Leishmania amazonensis exhibited VDAC blockage qualitatively similar to mammalian tubulins, but quantitatively there were some differences, possibly because of the extensive posttranslational modifications (PTMs) in CTT of Leishmania tubulin.

Tubulin Decreases Respiration Rate of Isolated Mitochondria.

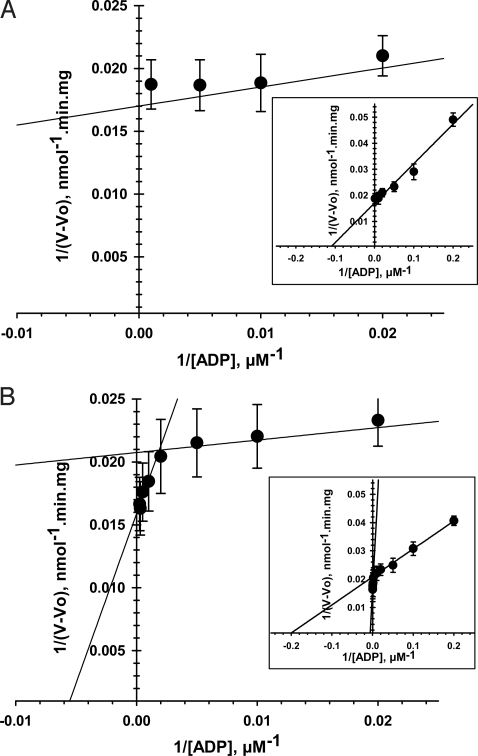

Our results demonstrate that tubulin can induce reversible blockage of VDAC and hence should be able to regulate ATP/ADP flux across MOM. Can tubulin do so in the intact mitochondria? To answer this question, we conducted experiments on isolated mitochondria. Oxygen consumption of isolated brain and heart mitochondria in response to successive additions of ADP was measured by using oxygraph. The value of apparent Km for exogenous ADP represents the availability of ADP for ANT to activate oxidative phosphorylation. The classic value of the Km for ADP of isolated mitochondria is ≈10–20 μM (21), and the linearization of its kinetic of respiration is shown in Fig. 5A. Addition of 1 μM tubulin resulted in the appearance of a second component of mitochondria respiration kinetics with Km of (169 ± 52) μM, >20 times higher than the first component (7 ± 2 μM; Fig. 5B and Table 1). The high Km component accounts for ≈30% of the total ADP flux in mitochondria. Similar results were obtained with mitochondria from heart (Table 1). Thus, there is tubulin binding to mitochondria as seen from the second component with high Km. Furthermore, the absence of variation of the maximal rate of respiration, Vmax (Table 1) between the control and the second component of the respiration kinetics in presence of tubulin, highlights the integrity of the respiratory chain (22). A possible explanation for the persistence of the first component (population of VDAC unaffected by tubulin) could be different affinity of tubulin to VDAC isomers 1, 2, and 3. There could also be other factors that compete with tubulin for VDAC binding, like hexokinases, which have been reported to bind to MOM directly through VDAC or close by (23), possibly obstructing tubulin access to VDAC. However, the precise nature of the 2 components is not clear at this time and needs further careful studies.

Fig. 5.

Tubulin dramatically increases apparent Km for ADP in regulation of respiration of isolated brain mitochondria. Shown are double-reciprocal representations of the respiration kinetics of brain mitochondria activated by ADP in control (A) and in the presence of 1 μM tubulin (B). The 2 straight lines represent 2 different respiration kinetics in the presence of tubulin (B). (Insets) Enlargements of A and B. Each data point is a mean of 6–9 independent experiments ±SE.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of respiration in brain and heart isolated mitochondria with 1 μM tubulin and without it

| Brain mitochondria (n = 6–9) | Apparent Km (ADP), μM | Vmax, nmol O2/min/mg |

| Without tubulin | 9 ± 1 | 55 ± 5 |

| With tubulin | ||

| First component | 7 ± 2 | 49 ± 15 |

| Second component | 169 ± 52 | 61 ± 15 |

| Heart mitochondria (n = 4–6) | ||

| Without tubulin | 11 ± 2 | 216 ± 11 |

| With tubulin | ||

| First component | 9 ± 5 | 136 ± 9 |

| Second component | 330 ± 47 | 241 ± 10 |

Each value is a mean of n experiments ± SE.

The interaction of other cytosolic proteins with VDAC may be important for regulation of tubulin–VDAC binding. Tubulin is an abundant and stable protein, present in many cells at concentrations higher than those shown here to block VDAC. We suggest that tubulin–VDAC interaction may be modulated through competition with other proteins that bind to VDAC, preventing tubulin binding. Another possibility is that PTM of VDAC or tubulin may alter this interaction. This possibility is particularly intriguing because PTMs of tubulin mostly occur on the CTT (24), the locus of interaction with VDAC. Under physiological conditions, tubulin concentration does not change dramatically. However, it is worth mentioning here that in cells exposed to microtubule-targeting drugs such as colchicine or paclitaxel (Taxol), the balance between tubulin dimers and polymerized tubulin can change. This might affect cytosolic tubulin dimer concentration and alter tubulin–VDAC interaction.

Evolutionary Considerations.

These results raise interesting evolutionary questions. Tubulin is a very old protein, found in all eukaryotes (25). This raises the question of whether the interaction we show here plays a role throughout the eukaryotic world. In support of this, we have shown that similar results are obtained with VDACs from rat or Neurospora, and with tubulin from rat or Leishmania. We can also approach this question by comparing the sequences of VDAC and tubulin from many species.

VDAC sequences (nearly 250) are known from plants, animals, fungi, stramenopiles, alveolates, rhodophyta, and charophyta, and functional data exist for VDAC from a number of organisms (26). Functional and structural properties of VDAC are preserved, although a great deal of sequence variation is found.

Tubulin sequences are known from throughout eukaryotes and reveal remarkable sequence conservation (27). A notable exception is the region of tubulin in the CTT, which shows significant sequence variation, both between isotypes in a given species and between species.

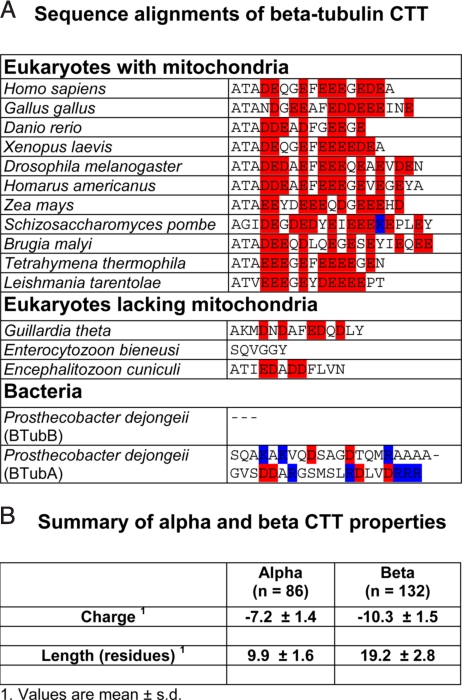

Although CTT sequences vary significantly, the functional properties that we found to be involved in VDAC–tubulin interaction are remarkably conserved throughout eukaryotic α- and β-tubuins, with a few significant exceptions to be discussed below. This is shown in alignments of β-CTT in Fig. 6A and in more extensive alignments of α- and β-CTT in Fig. S4. Our analysis shows that CTT length and charge are highly conserved in cells that contain mitochondria. Summary statistics for ≈100 α- and β-CTT sequences from our alignments and from ref. 27 are presented in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of tubulin CTT sequences. (A) Sequence alignments of β-tubulin CTT. Full sequences were aligned, but only the CTT, defined as the residues from C-terminal to the last residue in the crystal structure, are shown. Acidic residues are shown in red, basic residues in blue. More extensive alignments of both α-and β-CTT are in Fig. S4. (B) Summary of length and charge values for α- and β-CTT, taken from our alignments and from the data in ref. 27. Each value is a mean ± SD; n, number of species.

Tubulins with highly altered length or charge and that are the sole α or β gene in the organism are found only in organisms that do not have mitochondria (although not all organisms that lack mitochondria have altered CTT; see Fig. S4). Examples of altered tubulin CTT are from obligate intracellular eukaryotes that lack functional mitochondria and contain tubulin CTT much shortened in length and reduced in charge, including total loss of charge (Fig. 6 and Fig. S4). In addition, genes for α- and β-tubulins are found in bacteria (Prosthecobacter species) (28), likely the result of horizontal gene transfer from an unknown eukaryote (29). Although their function in the bacterial cell is unclear, these tubulins have essentially the same 3D structure as mammalian tubulin and exhibit GTP-dependent polymerization (29). However, the CTT differ radically from mammalian tubulin, perhaps in part because of the absence of mitochondria and hence loss of selection to maintain a CTT that can interact with VDAC. Both length and charge of the CTT, features that are highly conserved in eukaryotes, seem free to vary widely in Prosthecobacter, ranging from total loss to significant extension in length and acquisition of positive charges (Fig. 6A).

We suggest that the conservation of CTT length and charge in tubulins from organisms with functional mitochondria is caused in part to selective pressure to maintain tubulin CTT–VDAC interaction and thereby cytoplasmic regulation of mitochondrial energetics [although clearly other factors are also important, such as the evolutionarily conserved PTM that occur here (30)]. Conversely, the divergence in length and charge seen in some eukaryotes that lack functional mitochondria and in bacteria is because of the absence of this selective pressure.

Conclusions

We find that nanomolar concentrations of tubulin vastly increase VDAC sensitivity to voltage and could induce VDAC closure at low transmembrane potentials. Tubulin interaction with VDAC requires the presence of anionic CTT on the intact protein. This suggests a completely new role for dimeric tubulin and its charged CTT. Established roles for tubulin CTT have been dominated by interactions with microtubule-severing proteins (31), motor proteins (32), and plus-end-binding proteins (33), as well as being the site of PTM (34). We propose a model for tubulin–VDAC interaction in which the tubulin CTT penetrates into the channel lumen, potentially reaching through the channel because of the length of the CTT, interacting with a positively charged domain of VDAC. Because of this interaction, VDAC has a high affinity for CTT, which partially blocks channel conductance (Fig. 4). Identification of which CTT, α, β, or both, blocks VDAC is a subject of future research.

The tubulin-induced increase of Km for ADP in isolated mitochondria is evidence of a significant drop of the availability of ADP to ANT and partial restoration of the Km found in permeabilized cells. Thus, a mechanism for increasing Km by decreasing ATP/ADP permeability through MOM is closure of VDAC by tubulin. By this type of control, tubulin may selectively regulate metabolic fluxes between mitochondria and cytoplasm (35, 36).

Conservation of tubulin CTT length and charge and VDAC folding pattern throughout mitochondria-containing eukaryotes suggest that this interaction is widespread and ancient. Our experimental results with tubulins and VDAC from distantly related organisms demonstrate this. The loss of tubulin CTT properties only in organisms that lack mitochondria reinforces this view. Our results not only identify a previously unknown mechanism of regulation of MOM permeability and mitochondria respiration, but also identify a functional role for the cytoskeletal protein, dimeric tubulin.

Materials and Methods

Protein Purification.

VDAC from rat liver or N. crassa mitochondrial outer membranes was isolated and purified as described in ref. 37 and were a generous gift of M. Colombini (University of Maryland, College Park, MD). Bovine brain tubulin and rabbit muscle actin were obtained from Cytoskeleton. Rat brain tubulin was purified as described in ref. 38 (see SI Materials and Methods). Tubulin-S was produced by subtilisin cleavage of rat brain tubulin as described in ref. 39. Peptides corresponding to the CTT of α- and β-tubulins were obtained from Sigma–Genosys. The sequence of the synthetic peptide corresponding to the CTT is that of the bα-1 isotype, EVGVHSVEGEGEEEGEEY, whereas the β-sequence is that of the βI isotype, DATAEEEEDFGEEAEEEA.

Electrophysiological Recordings.

Planar lipid membranes were formed from monolayers made from 1% (wt/vol) of lipids in hexane on 70- to 80-μm-diameter orifices in the 15-μm-thick Teflon partition that separated 2 chambers as described in ref. 40. The lipid-forming solutions contained diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPhPC) or asolectin and cholesterol (10:1 wt/wt). DPhPC and asolectin (soybean phospholipids) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, and cholesterol was purchased from Sigma. VDAC insertion was achieved by adding 0.1–1.5 μL of a 1% Triton X-100 solution of purified VDAC to the 1.2-mL aqueous phase in the cis compartment while stirring. Potential is defined as positive when it is greater at the side of VDAC addition (cis). After channels were inserted and their parameters were monitored, tubulin was added to one or both sides of the membrane under constant stirring for 2 min. Conductance measurements were performed as described in ref. 40 (see SI Materials and Methods). Amplitude, lifetime, and fluctuation analysis was performed by using Clampfit 9.2 (Axon Instruments).

Mitochondria Respiration Measurements.

Brain and cardiac mitochondria were isolated as described (11, 41) (see SI Materials and Methods). All measurements of respiration rates were performed by using the high-resolution respirometry (Oroboros Oxygraph) with substrates of 10 mM succinate for brain mitochondria and 5 mM glutamate and 2 mM malate for heart mitochondria. Oxygen solubility in the Mitomed solution was taken to be 225 μM at 25 °C. Kinetics of activation of respiration in mitochondria was studied by increasing successively the final concentrations of ADP (5–10−20–50–100-200–500-1,000–2,000–3,000 μM) in the absence or in presence of 1 μM tubulin, with 0.2% of BSA and 1 UI apyrase for ADP regeneration. Mitochondria were incubated with 1 μM tubulin 30 min at room temperature (25 °C) before introduction in the oxygraphy chamber. Mitochondrial apparent Km for ADP and proportion of each component of respiration kinetics were calculated as described in ref. 42.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (T.K.R., K.S., E.H., S.M.B., and D.L.S.) and by Agence National de la Recherche Project BLAN07–2_188128, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, France (to C.M. and V.S.). V.S. was also supported by Estonian Science Foundation Grants 6142 and 7117.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Tubulin in all experiments was dimeric, not polymerized, because there was no GTP or Mg2+ added, and the total tubulin concentration was at least 100-fold below the critical concentration for polymerization in the presence of GTP and Mg2+.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0806303105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Colombini M. VDAC: The channel at the interface between mitochondria and the cytosol. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;256–257:107–115. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009862.17396.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemasters JJ, Holmuhamedov E. Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) as mitochondrial governator: Thinking outside the box. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Sheiko T, Craigen WJ, Molkentin JD. Voltage-dependent anion channels are dispensable for mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:550–555. doi: 10.1038/ncb1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostovtseva TK, Tan W, Colombini M. On the role of VDAC in apoptosis: Fact and fiction. J Bionenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:129–142. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-6566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial apoptosis without VDAC. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:487–489. doi: 10.1038/ncb0507-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yagoda N, et al. RAS–RAF–MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature. 2007;447:864–886. doi: 10.1038/nature05859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombini M, Blachly-Dyson E, Forte M. VDAC, a channel in the outer mitochondrial membrane. In: Narahashi T, editor. Ion Channels. New York: Plenum; pp. 169–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rostovtseva T, Colombini M. ATP flux is controlled by a voltage-gated channel from the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28006–28008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan W, Colombini M. VDAC closure increases calcium ion flux. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:2510–2515. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appaix F, et al. Possible role of cytoskeleton in intracellular arrangement and regulation of mitochondria. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:175–190. doi: 10.1113/eph8802511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saks VA, et al. Control of cellular respiration in vivo by mitochondrial outer membrane and by creatine kinase. A new speculative hypothesis: Possible involvement of mitochondrial–cytoskeleton interactions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:625–645. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernier-Valentin F, Rousset B. Interaction of tubulin with rat liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7092–7099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carré M, et al. Tubulin is an inherent component of mitochondrial membranes that interacts with the voltage-dependent anion channel. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33664–33669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasenick MM, Donati RJ, Popova JS, Yu JZ. Tubulin as a regulator of G-protein signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2004;390:389–403. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santander VS, et al. Tubulin must be acetylated in order to form a complex with membrane Na+,K+-ATPase and to inhibit its enzyme activity. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;291:167–174. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sackett DL, Bhattacharyya B, Wolff J. Tubulin subunit carboxyl termini determine polymerization efficiency. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priel A, Tuszynski JA, Woolf NJ. Transitions in microtubule C-termini conformations as a possible dendritic signaling phenomenon. Eur Biophys J. 2005;35:40–52. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemeshko VV. Theoretical evaluation of a possible nature of the outer membrane potential of mitochondria. Eur Biophys J. 2006;36:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X, Forbes JG, Colombini M. Actin modulates the gating of Neurospora crassa VDAC. J Membr Biol. 2001;180:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s002320010060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan W, Loke YH, Stein CA, Miller P, Colombini M. Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides block the VDAC. Biophys J. 2007;93:1184–1191. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vignais P. Molecular and physiological aspects of adenine nucleotide transport in mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;456:1–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(76)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholls D, Ferguson SJ. Bioenergetics. London: Academic; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robey RB, Hay N. Mitochondrial hexokinases, novel mediators of the antiapoptotic effects of growth factors and Akt. Oncogene. 2006;25:4683–4696. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond JW, Cai D, Verhey KJ. Tubulin modifications and their cellular functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margulis L, Chapman M, Guerrero R, Hall J. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA): Acquisition of cytoskeletal motility from aerotolerant spirochetes in the Proterozoic Eon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13080–13085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604985103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young MJ, Bay DC, Hausner G, Court DA. The evolutionary history of mitochondrial porins. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuszynski JA, et al. The evolution of the structure of tubulin and its potential consequences for the role and function of microtubules in cells and embryos. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:341–358. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052063jt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins C, et al. Genes for the cytoskeletal protein tubulin in the bacterial genus Prosthecobacter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:17049–17054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012516899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlieper D, Oliva MA, Andreu JM, Löwe J. Structure of bacterial tubulin BtubA/B: Evidence for horizontal gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9170–9175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502859102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westermann S, Weber K. Post-translational modifications regulate microtubule function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:938–947. doi: 10.1038/nrm1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roll-Mecak A, Vale RD. Structural basis of microtubule severing by the hereditary spastic paraplegia protein spastin. Nature. 2008;451:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature06482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skiniotis G, et al. Modulation of kinesin binding by the C termini of tubulin. EMBO J. 2004;23:989–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mishima M, et al. Structural basis for tubulin recognition by cytoplasmic linker protein 170 and its autoinhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10346–10351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703876104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verhey KJ, Gaertig J. The tubulin code. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2152–2160. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.17.4633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saks V, et al. Cardiac system bioenergetics: Metabolic basis of the Frank–Starling law. J Physiol. 2006;571:253–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.101444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saks V, Vendelin M, Aliev MK, Kekelidze T, Engelbrecht J. Mechanisms and modeling of energy transfer between and among intracellular compartments. In: Gibson GF, Dienel G, editors. Brain Energetics: Integration of Molecular and Cellular Processes. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 815–860. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blachly-Dyson E, Peng SZ, Colombini M, Forte M. Alteration of the selectivity of the VDAC ion channel by site-directed mutagenesis: Implication for the structure of a membrane ion channel. Science. 1990;247:1233–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.1690454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolff J, Sackett DL, Knipling L. Cation-selective promotion of tubulin polymerization by alkali metal chlorides. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2020–2028. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knipling L, Hwang J, Wolff J. Preparation and properties of pure tubulin S. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1999;43:63–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)43:1<63::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rostovtseva TK, Kazemi N, Weinrich M, Bezrukov SM. Voltage gating of VDAC is regulated by nonlamellar lipids. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37496–37506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Booth RF, Clark JB. A rapid method for the preparation of relatively pure metabolically competent synaptosomes from rat brain. Biochem J. 1978;176:365–370. doi: 10.1042/bj1760365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saks V, et al. Permeabilized cell and skinned fiber techniques in studies of mitochondrial function in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;184:81–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.