Abstract

Acute injury-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction occurs even in young and otherwise healthy individuals after major injuries, and significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with pre-existent cardiac diseases as well as in patients who develop multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Recent studies indicate that post-injury acute cardiac failure is the result of an exaggerated cardiac inflammatory response resulting in an inflammatory cardiomyopathy characterized by decreased cardiac contractility. Over the past decade, many of the effector molecules involved in this process have been identified as having some involvement in generating a myocardial inflammatory response. However, less is known about the agents and processes involved in triggering this inflammation-induced decrease in cardiac contractility. Consequently, in this review, the concept of the heart responding to major injury like an innate immune organ will be presented, the various effector molecules and mechanisms leading to myocyte contractile dysfunction will be reviewed and data indicating that the acute cardiac contractile dysfunction observed after trauma is due to gut-derived intestinal lymph factors will be reviewed.

Keywords: Mesenteric lymph, trauma-hemorrhage, burn, cardiac dysfunction

Introduction

Acute heart failure (AHF) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in ICU patients. Although primary cardiac diseases represent the most common cause of AHF in ICU patients, there has been an increasing recognition that an acute acquired state of myocardial dysfunction can also occur in patients without primary heart disease in patients with burns, major trauma, sepsis or shock [1-4]. This acquired state of acute cardiac dysfunction has been documented in patients without intrinsic cardiac disease indicating that these inflammatory stress states can lead to myocardial dysfunction even in patients with a healthy heart. In contrast to patients with primary cardiac diseases, this acquired secondary cardiac depressive state is reversible and cardiac function generally returns to normal when the initiating condition has resolved [1,3]. Two major theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of acute myocardial dysfunction. The first theory was based on the notion that burn, trauma, shock or sepsis-induced acquired myocardial dysfunction was due to decreased myocardial perfusion leading to an ischemic injury. However, based on the observations that this cardiac dysfunctional state was reversible and that there was no evidence of myocardial necrosis or impaired myocyte microvascular perfusion, this first theory has given way to a second theory focusing on the inflammatory response [1,3]. In this inflammatory-induced cardiac depressant model, functional rather than structural changes seem to be responsible for intrinsic myocardial depression and it has been proposed that endogenously produced pro-inflammatory factors are the effectors leading to an impaired myocardial contractile state. The data supporting this notion of an inflammatory cardiomyopathy is consistent with a large body of literature documenting that conditions such as burns, trauma and shock produce a profound systemic inflammatory response characterized by increased levels of circulating proinflammatory mediators, leukocyte activation, microvascular leak, and organ dysfunction [5].

Clinical trauma and shock-induced cardiac dysfunction is characterized by contraction and relaxation deficits, although cardiac output is generally normal or elevated [1,4]. Even though this myocardial contractile dysfunction state is not generally associated with a decrease in cardiac output, it does result in myocardial stress as reflected by a decreased ejection fraction, increased myocardial metabolic demands and an elevated heart rate, none of which are beneficial in the systemically stressed individual. Since the majority of burn and trauma victims are young and have no intrinsic heart disease, they generally tolerate this cardiac depressant state. However, in the subpopulation of elderly patients, patients with pre-existent left ventricular dysfunction or decreased cardiac reserve, or patients with multiple organ dysfunction, this additional cardiac insult can lead to significant hemodynamic disturbances and adversely affect clinical outcome. Consequently, studies directed at understanding and reversing this acquired cardiac depressant state has been an intense area of research. Within this context, the goal of this review is to provide a brief overview of the inflammatory cardiac depressant model, and then present the results of our recent studies indicating that myocardial depression after burns or trauma-hemorrhage is induced by factors exiting the gut via the intestinal lymphatics.

Inflammatory Cardiac Depressant Model

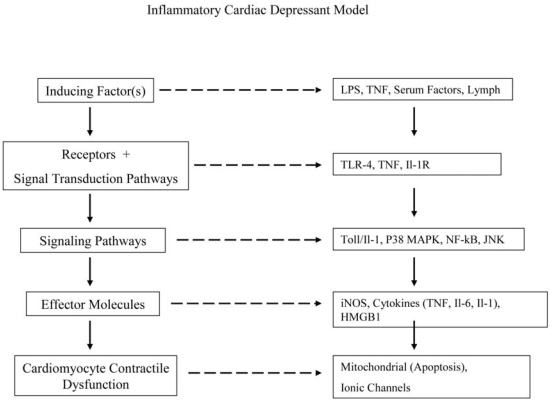

There are many lines of evidence supporting the concept that burn and trauma-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction represents an inflammatory cardiomyopathy. These include both clinical and experimental studies showing that traditional inflammatory mediators, especially the cytokines TNF, IL-1 and IL-6 as well as nitric oxide can lead to cardiac contractile depression and that their inhibition or neutralization abrogates burn- or trauma-shock-induced myocardial depression [1,6]. Furthermore, studies also indicate that the heart can function as an innate immune-responsive organ since cardiomyocytes produce cardio-depressant cytokines (TNF, IL-6, IL-1) as well as iNOS-derived nitric oxide and express Toll-like receptors (TLR) [7,8]. In fact, the induction of myocardial contractile dysfunction in experimental burn, trauma-shock, as well as other conditions appears to involve a TLR4-dependent signaling pathway [8-11]. These observations that cardiomyocytes appear to share many properties with innate immune cells, such as signaling through TLR4 and the production of cytokines and nitric oxide, have provided insight into the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of acute trauma-induced myocardial depression. In fact, similar pathways have been documented in experimental models of myocardial infarction [12] as well as in the pathogenesis of chronic heart failure [13]. This notion that the heart functions as an innate immune organ has provided new and important insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms leading to contractile dysfunction. The major identified pathways by which cardiac depressant-inducing factors lead to cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the inflammatory myocardial contractile depressant model, with the general pathway illustrated on the left and specifics of these pathways on the right Although the pathway is illustrated as a linear system to aid in clarity, the in vivo responses are more complex with many of the effector factors, such as TNF, IL-1 or nitric oxide, being able to serve as inducing factors as well. In this way certain inflammatory products can initiate a positive feed-back loop and thereby amplify the inflammatory response.

The paradigm of various factors interacting with receptors on cardiomyocytes and leading in turn to the production of a number of cardio-depressant effector molecules through various signaling pathways appears straight-forward (Figure 1). However, the actual system appears to be more complex. For example, several of the cardio-depressant effector molecules, especially TNF, IL-1 and nitric oxide, can serve as activators of this inflammatory cascade as well as effectors [1,2,3,6]. Consequently, these molecules exert a feed-forward effect (positive feed-back loop), where their presence further increases their production thereby amplifying the inflammatory response and leading to further myocyte dysfunction. Additionally, some steps of this pathway are better understood than others, with the source and nature of the post-burn or post-trauma factors that induce this response being one of the least understood.

Based on our experimental studies implicating gut-derived factors carried in the mesenteric lymph as the source of factors leading to lung and other organ injuries as well the induction of a systemic inflammatory state after burn injury or trauma-hemorrhage [14], we hypothesized that gut-derived factors may also be involved in cardiac dysfunction. If this was true, then one of the major sources of the initiating factors leading to cardiac contractile dysfunction would have been identified. Furthermore, the collection of intestinal lymph would provide a unique opportunity to isolate and identify the exact factors responsible for triggering this inflammatory cascade leading to myocardial inflammation and contractile dysfunction. That is, by collecting lymph prior to it's reaching the systemic circulation, we would obviate the confounding effects of any secondary cardio-active mediators induced by the lymph factors. Specifically, by identifying the gut lymph as the source of the primary factors leading to contractile dysfunction, we could collect the fluid containing the initiating factors early and prior to the generation of secondary mediators. The next section of this review will address our studies on the role of gut lymph in burn-induced and trauma-shock-induced myocardial dysfunction.

Role of Gut-derived Factors in Mesenteric Lymph as the Trigger that Induces Early Acute Post-burn and Post-trauma Myocardial Contractile Dysfunction

Although the etiology of injury- and shock-induced cardiac dysfunction is likely multifactorial, the sources and the exact identities of the factors that initiate this process remain to be definitively identified. Since major thermal injuries, mechanical trauma, and hemorrhagic shock lead to splanchnic ischemia, gut injury, and gut-induced systemic inflammation and distant organ dysfunction is a well recognized phenomenon [5]. One possibility is that gut-derived factors contained in mesenteric lymph contribute to the acquired cardiac dysfunction observed shortly after major trauma as well as hemorrhagic shock. This notion was based on our recent studies showing that mesenteric lymph duct ligation before a burn injury [15] or an episode of trauma-hemorrhage [16-18] protects against burn- or trauma-shock (T/HS)-induced lung injury, and limits pulmonary neutrophil sequestration as well as the dysfunction of other organs and cellular systems [14]. These results led us to hypothesize that the cardiac dysfunction after major burn injuries or T/HS may be mediated, at least in part, by factors released from the gut and transported in the mesenteric lymph. To test this hypothesis, we initially examined whether mesenteric lymph duct ligation would protect against myocardial contraction and relaxation defects. We chose to perform mesenteric lymph duct ligation as a first step in testing this hypothesis, because ligation of the mesenteric lymph duct would prevent any gut-derived myocardial depressant or depressant-inducing factors from reaching the systemic circulation and hence the heart. As will be described further in this section, the results of our published studies utilizing a burn model as well as our unpublished T/HS results indicate that gut-derived factors carried in the mesenteric lymph serve as the initial triggers that induce early post-burn or post-T/HS cardiac dysfunction.

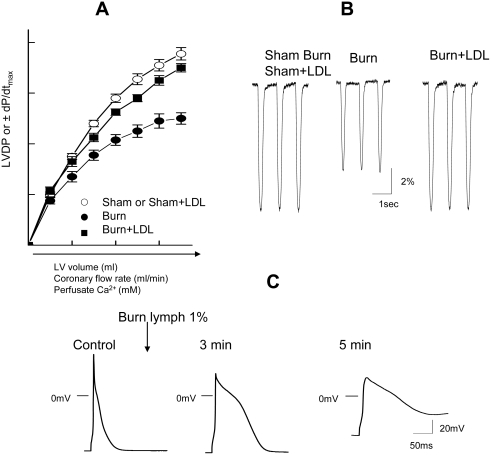

In our first study [19], male rats were subjected to a laparotomy with or without mesenteric lymph duct ligation (LDL). After LDL or sham-LDL, the rats were randomized to receive either sham or actual 43% body surface area full-thickness scald burns. They were then resuscitated with 4 ml/kg/%burn of Ringer's lactate over 24 hrs and then killed. At sacrifice, the hearts were removed, mounted on a Langendorff apparatus and cardiac function assessed by measuring the contractile response to increases in 1) preload, 2) coronary flow rate or 3) perfusate Ca2+ concentration. Specifically, left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) and the maximal rate of LVP pressure rise and fall (±dP/dt) to these stimuli were quantified. As schematically illustrated in Figure 2A, the hearts harvested from the burn group showed a significant impairment in contraction and relaxation when preload, coronary flow or perfusate Ca2+ was increased as compared to the sham-burned or the burn+LDL groups. These observations that pre-burn lymph duct ligation totally prevented burn-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction supports the global hypothesis that the gut is the source of myocardial depressant factors that directly or indirectly induce burn-induced myocardial dysfunction.

Figure 2.

A)Schematic presentation of impaired LV performance and the prevention by LDL in hearts following burn injury. Changes in LVDP and the maximal rate of LVDP (±dP/dt) in response to increasing preload, coronary flow rate or purfusate Ca2+ concentration. Note: In control rat hearts, LVDP was increased with increasing these factors. Responses to these changes were depressed in burn but this dysfunction was prevented by LDL. B) Typical cell shortening in myocytes isolated from sham burn or sham burn+LDL, burn and burn+LDL hearts. We observed that cell shortening (%) and rate of relaxation (dL/dt) were significantly slower in myocytes from post-burn hearts compared with myocytes from sham burn or sham+LDL. There was no significant change in contractility in myocytes from burn+LDL hearts. C) Typical effects of burn lymph (1%) on action potential recorded in rat LV myocytes. Schematic action potentials recorded at different time points control before, 3 min after the application of burn lymph. Note: significant changes in action potential configuration and resting membrane potential.

To better characterize the cellular nature of the myocardial dysfunction observed after burn injury, we examined the contractile response of left ventricular myocytes harvested 24 hours after sham or actual burn injury in rats that received or did not receive LDL [20]. As schematically illustrated in Figure 2B, cardiac myocyte contractility was reduced in the myocytes from the burned but not the burn+LDL or sham burn rats. Since changes in cardiac myocyte excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling due to abnormal Ca2+ handling at the cellular level are involved in the initiation and progression of myocardial contractile depression, we next examined Ca2+ transients in these animals. Calcium transients were chosen for study because a decrease in stimulated Ca2+ influx could account for the decrease in myocyte contractility observed in the burn myocytes. These studies documented that the decrease in post-burn myocyte contractility was associated with a 20% decrease in the amplitude of Ca2+ transients without any changes in cellular resting Ca2+ levels or the Ca2+ content of the sarcoplasmic reticulum [20]. Next, since Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channel (lca) is a key determinant of cardiac contractility and could provide an explanation for the markedly altered Ca2+ transients, we examined lca activity in the myocytes. These studies showed that the lca activity was decreased by 30%. Furthermore, this decrease in lca activity was found to be due to an absolute decrease in the number of actual or functional L-type Ca2+ channels, rather than to a decrease in the number of open channels [20]. Of importance, just as LDL prevented burn-induced myocyte contractile dysfunction, it also prevented these changes in myocyte Ca2+ physiology. Thus, mechanistically, this study suggests that the decreased contractility observed in the myocytes from the post burn hearts most likely involves a decrease in Ca2+ influx due to a reduced lca density. These cell-based studies thus implicate an impairment of Ca2+ handling at the cellular level in burn-induced myocyte contractile dysfunction and are also consistent with whole heart studies documenting the failure of increasing extracellular Ca2+ levels to normalize ventricular contractility after burn injury [19,21].

Since these LDL studies indicated that factors in the mesenteric lymph are involved in the pathogenesis of burn-induced myocardial depression, it appeared that in vitro studies of burn lymph would provide a unique opportunity to gain further insight into cellular mechanisms that lead to abnormal myocyte cellular calcium homeostasis after burn injury. Thus, we examine the direct effects of intestinal lymph from burned and sham-burned rats on E-C coupling in normal rat ventricular myocytes [22, 23]. In these studies, we tested the effects of burn and sham-burn lymph on myocytes over a dose-response range (0.1-5% v/v concentration) and found that the inotropic effects of burn lymph varied depending on the concentration tested, while sham burn lymph had no activity. At the lowest concentrations (< 0.5%), burn lymph increased the amplitude of myocardial contractions (positive inotropic effects), while, at higher concentrations (0.5-5%), burn lymph resulted in a transient increase in contractility followed by a rapid and sustained decrease in myocyte contractility. Although in vitro burn lymph had a dual effect on myocyte contractility based on the concentration tested, it is important to consider that the in vivo peak plasma concentration of burn lymph would conservatively be in the range of 3-5% (based on the volume of lymph produced and the blood volume of the rat). Consequently, the negative inotropic effects of burn lymph would predominate in vivo, a finding that is consistent with the in vivo lymph duct ligation studies. Studies of myocyte action potentials helped clarify the mechanisms underlying the dual (initial positive followed by negative) inotropic effects of burn lymph. As schematically illustrated in Figure 2C, the addition of 1% or greater burn lymph resulted in an early increase in the duration of the action potential that lasted from 1 to 3 minutes. This early prolongation of the action potential was associated with an increase in calcium transients and increased contractility. However, after 5 minutes of exposure to burn lymph, the myocytes had lost the ability to completely repolarize and the membrane potential remained elevated in subsequent action potentials. This burn lymph-induced myocyte depolarization explains the negative inotropic effects of burn lymph. Thus, burn lymph appears to alter myocyte contractility through its effects on cellular excitability.

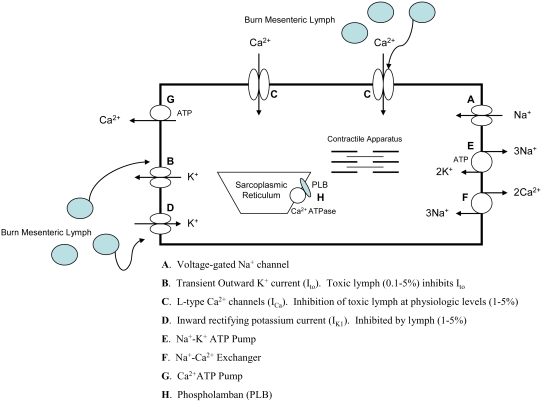

Since the action potential of myocytes is controlled by changes in the cells ionic channels, we next investigated the effects of burn lymph on K+ and Ca2+ current channels to help clarify the ionic mechanisms responsible for the effects of burn lymph on myocyte contractility and the action potential [22,23]. The result of this work is summarized in Figure 3. Exposure of myocytes to burn lymph induced an initial increase in myocyte contractility and prolongation of the action potential, which was due to inhibition of transient outward K+ currents (Ito), which resulted in a net Ca2+ influx. However, this initial prolongation of the action potential was soon followed by a reduction of the plateau potential, membrane depolarization and a decrease in contractility. These changes in the configuration of the action potential were associated with a large decrease in lca. Thus, it is likely that the block of lca counter balanced the block of Ito, leading to a decrease in the net Ca2+ influx. These effects may be directly responsible for the negative inotropic effects observed with higher concentration of burn lymph. In addition to lca, the inward rectifying k+ channel current (Ik1) was also influenced by higher concentrations of burn lymph. An inhibition of IK1 may be responsible for the inability of the cell to completely repolarize (Figure 2C). Thus, our data shows that burn lymph modulates myocyte contractility, at least in part, by direct effect on lca and Ik1, which then results in a decreased action potential overshoot and membrane depolarization.

Figure 3.

In ventricular myocytes, contraction is initiated by Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ channels (also termed the ryanodine receptors) triggered by a rapid Ca2+ influx via ICa. The SR is the major and possibly exclusive store of releasable Ca2+ in the heart, and the fraction of Ca2+ release is strongly influenced by both the level of Ca2+ influx and the SR Ca2+ content. In the heart, Ca2+ influx via Na+-Ca2+ exchanger appears to play a negligible role as a trigger for Ca2+ release from the SR. This process is reversed by the active re-uptake of Ca2+ into the SR by a Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and outward Ca2+ transport via the sarcolemmal Na+-k+ pump and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. SERCA is under reversible regulation by phospholamban (PLB) in the SR membrane.

In unpublished studies, we have also tested the role of the gut and gut lymph in the pathogenesis of the decrease in myocardial contractility observed after trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS). The rationale for these studies has been described above and focused on our earlier work showing that T/HS-induced acute lung injury as well as post-shock SIRS is related to gut-derived factors present in mesenteric lymph [14]. In these studies, rats were subjected to sham-shock (SS) or actual hemorrhagic shock (HS) (30-35 mm Hg × 90 minutes) plus trauma (T) in the form of a laparotomy. In the first set of studies, cardiac contractility was assessed via the ex vivo whole heart Langendorff model at 24 hrs after T/HS or T/SS. We found that cardiac contractility was significantly decreased in the T/HS group as compared to the sham-shock group. In this study, the left ventricular response (LVDP and ±dP/dt) to changes in coronary blood flow and extracellular Ca2+ were measure in a fashion similar to that described in the burn studies. Just as was seen in the burn studies, mesenteric lymph duct ligation (T/HS + LDL) abrogated T/HS-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction further validating the global hypothesis that during acute stress states associated with significant splanchnic hypoperfusion, the ischemic-reperfused gut generates bioactive factors carried in the mesenteric lymph that are capable of causing myocardial contractile depression. We next compared the effects of T/HS vs. T/SS lymph on normal left ventricular myocytes. The effects of T/HS lymph on myocyte contractility, Ca2+ transients and the action potential were strikingly similar to what was found with burn lymph, while T/SS lymph had no biologic activity. Thus, our unpublished studies in T/HS fully supported our burn studies and indicate that gut-derived mesenteric depressant factors carried in the intestinal lymph, but not the portal circulation, play a major role in the development of acute T/HS- as well as burn-induced myocardial contractile depression.

Although no attempts have been made to date to isolate and/or identify the factors in burn or T/HS lymph that are responsible for the acquired cardiac contractile dysfunction observed in these conditions, our studies and the work of others indicate that lymph contains both biologically-active tissue-injurious and pro-inflammatory lipid and protein factors [24-26]. Even though we do not know what the biologically active factors are in lymph, we have excluded a number of putative candidates, including cytokines, [27] bacteria, and bacterial products [28]. Additionally, our results are consistent with studies performed over twenty years ago showing the presence of myocardial depressant factors (MDF) in the thoracic lymph of dogs subjected to hemorrhagic shock [29] and in the serum of both burned animals and patients [30,31].

In trying to understand and elucidate the potential mechanisms by which burn or T/HS lymph depress myocyte contractile function, we have focused on the direct effects of these lymph samples on ionic channels. However, the cellular responses by which the ionic currents are affected by lymph remain to be determined. In this context, a great deal is understood about the function and acute modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels, but little is known about the control of channel expression. It is known that inflammatory mediators can induce the generation of specific cytokines, such as TNF or IL-1, as well as increase the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in cardiac myocytes [14]. Nitric oxide, in turn can interact with proteins involved in E-C coupling as both a positive or negative inotropic agent [32,33]. In fact, recent studies also indicate that nitric oxide can be involved in the regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels via nitrosylation [34]. This observation, plus our recent studies showing that the injection of T/HS lymph into normal rats up-regulates iNOS in the liver, lung and gut (heart not measured) [35], adds support to the notion that lymph mediates cardiac depression, at least in part, via an iNOS pathway. Based on this literature, it is thus possible that nitric oxide-mediated pathways play a role in the down-regulation of lea in post burn or post-shock hearts. However, further studies will be needed to validate this possibility as well as investigate the role of other inflammatory-induced mediators and signaling systems. Although both burn and T/HS lymph had direct effects on cardiac myocytes in vitro, it is also possible that some of lymph's effects on cardiac depression in vivo may be indirect and secondary to the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines or other biologically-active in other organs or cells which then act on the myocyte. Thus, our studies have not ruled out the possibility that part of lymph's cardiac depressant activities in vivo may be indirect.

Therapeutic Options

Even though many patients with measurable evidence of cardiac contractile dysfunction show no obvious clinical signs of heart failure, there are subgroups of patients where this process is of clinical importance. These patient populations include elderly patients with limited cardiac reserve, patients with pre-existent cardiovascular disease and patients sustaining massive injuries. Thus, it is in these patients that it will be important to identify successful therapeutic strategies to limit the development and/or treat post-trauma and post-burn cardiac contractile depression once it occurs. In developing these therapies, recognition that the stressed gut is a source of these cardiac depressant factors has several important implications. First, this fact indicates that gut-directed therapeutic strategies may also benefit the heart. Secondly, the knowledge that these factors are in gut lymph will facilitate their isolation and subsequent identification, thereby helping to clarify processes leading to cardiac contractile dysfunction. Additionally, the development of therapies directed at blocking the primary (gut-derived) mediators that initiate the processes leading to myocyte contractile dysfunction are likely to be more successful than attempts at blocking secondary cardio-depressant factors, such as TNF. This notion is supported by multiple clinical studies showing that the strategy of blocking a specific inflammatory mediator (i.e. LPS, TNF, NO, etc.) have failed. This clinical failure of therapies directed at neutralizing specific mediators is largely due to the complexities of the inflammatory response as well as the redundant nature of the inflammatory pathways involved in tissue injury and dysfunction [36-38].

Conclusions

In summary, our working hypothesis of burn- or trauma-induced acute cardiac contractile dysfunction begins with a systemic insult that significantly reduces splanchnic blood flow leading to an intestinal ischemia-reperfusion event. In response to this decrease in intestinal blood flow, the stressed gut produces/liberates pro-inflammatory and tissue-injurious factors, which reach the systemic circulation via the mesenteric lymphatics rather than the portal venous system. These gut-derived lymph factors induce cardiac contractile dysfunction in two ways. First, they exert a direct effect on cardiomyocyte ionic channels which results in a decrease in contractile function. Secondly, these lymph factors trigger an inflammatory response within the heart, characterized by the production of cardio-depressant effector molecules, such as TNF or nitric oxide. The net effect of these lymph-induced cardiac processes is cardiomyocyte contractile depression and cardiac dysfunction. As more information evolves on the exact nature of these lymph molecules and the signaling pathways they activate, it is likely that new therapeutic strategies will emerge.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants GM-059841 (EAD), GM-069790 (EAD), HL-077480 (AY).

References

- 1.Carlson DL, Morton JW. Cardiac Molecular signaling after burn trauma. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:669–675. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000237955.28090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma AC. Sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. Shock. 2007;28:265–269. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235090.30550.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnagopalan S, Kumar A, Parrillo JE, Kumar A. Myocardial Dysfunction in the patient with sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8:376–388. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kline JA, Thorton LR, Lopaschuk GD, Barbee RW, Watts JA. Heart function after severe hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 1999;12:454–461. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deitch EA. Multiple organ failure. Pathophysiology and potential future therapy. Ann of Surg. 1992;216:117–134. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199208000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meldrum DR, Wang M, Tsai BM, Kher A, Pitcher JM, Brown JW, Meldrum KK. Intracellular signaling mechanisms of sex hormones in acute myocardial inflammation and injury. Front Bioscience. 2005;10:1835–1867. doi: 10.2741/1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen D, Assad-Kottner C, Orrego C, Torre-Amione G. Cytokines and acute heart failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S9–16. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000297160.48694.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemoto S, Valllego JG, Knuefermann P, Misra A, Defreitas G, Carabello BA, Mann DL. Escherichia coli LPS-induced LV dysfunction: role of toll-like receptor-4 in the adult heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2316–H2323. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng X, Ao L, Song Y, Raeburn CD, Fullerton DA, Harken AH. Signaling for myocardial depression in hemorrhagic shock: roles of Toll-like receptor 4 and p55 TNF receptor. Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 2005;288:600–606. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00182.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas JA, Tsen MF, White DJ, Horton JW. TLR4 inactivation and rBPI(21) block burn-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1645–H1655. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01107.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgarten G, Knuefermann P, Schuhmacher G, Vervolgyi V, von Rappard J, Dreiner U, Fink K, Djoufack C, Hoeft A, Grohe C, Knowlton AA, Meyer R. Toll-like receptor 4, nitric oxide and myocardial depression in endotoxemia. Shock. 2006;25:43–49. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000196498.57306.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyama J, Blais C, Jr, Liu X, Pu M, Kobzik L, Kelly RA, Bourcier T. Reduced myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;109:784–789. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112575.66565.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly RA, Smith TW. Cytokines and cardiac contractile function. Circulation. 1997;95:778–781. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deitch EA, Xu D, Kaiser VL. Role of the gut in the development of injury- and shock induced SIRS and MODS: the gut-lymph hypothesis, a review. Front Biosc. 2006;11:520–528. doi: 10.2741/1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnotti LJ, Xu D, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph: a link between burn and lung injury. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1333–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnotti LJ, Upperman JS, Xu D, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph but not portal blood increases endothelial cell permeability and promotes lung injury after hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1998;228:518–527. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambol JT, Xu D, Adams CA, Magnotti LJ, Deitch EA. Mesenteric lymph duct ligation provides long term protection against hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury. Shock. 2000;14:416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deitch EA, Adams C, Lu Q, Xu D. A time course study of the protective effect of mesenteric lymph duct ligation on hemorrhagic shock-induced pulmonary injury and the toxic effects of lymph from shocked rats on endothelial cell monolayer permeability. Surgery. 2001;129:39–47. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.109119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambol JT, White J, Horton JW, Deitch EA. Burn-induced impairment of cardiac contractile function is due to gut-derived factors transported in mesenteric lymph. Shock. 2002;18:272–276. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawai K, Kawai T, Sambol JT, Xu D, Yuan Z, Caputo FJ, Badami CD, Deitch EA, Yatani A. Cellular mechanisms of burn-related changes in contractility and its prevention by mesenteric lymph ligation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2475–H2484. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01164.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maass DL, White DJ, Sanders B, Horton JW. Cardiac myocyte accumulation of calcium in burn injury: cause or effect of myocardial contractile dysfunction. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:252–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yatani A, Xu D, Kim SJ, Vatner SF, Deitch EA. Mesenteric lymph from rats with thermal injury prolongs the action potential and increases Ca2+ transient in rat ventricular myocytes. Shock. 2003;20:458–464. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000090602.26659.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yatani A, Xu D, Irie K, Sano K, Jidarian A, Vatner SF, Deitch EA. Dual effects of mesenteric lymph isolated from rats with burn injury on contractile function in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H778–H785. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00808.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser VL, Sifri ZC, Dikdan GS, Berezina T, Zaets S, Lu Q, Xu D, Deitch EA. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph from rat contains a modified form of albumin that is implicated in endothelial cell toxicity. Shock. 2005;23:417–425. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000160524.14235.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dayal SD, Hasko G, Lu Q, Xu DZ, Caruso JM, Sambol JT, Deitch EA. Trauma/hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph upregulates adhesion molecule expression and IL-6 production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Shock. 2002;17:491–495. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez RJ, Moore EE, Biffl WL, Ciesla DJ, Silliman CC. The lipid fraction of post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph inhibits neutrophil apoptosis and enhances cytotoxic potential. Shock. 2000;14:404–408. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson MT, Deitch EA, Lu Q, Osband A, Feketeova E, Nemeth ZH, Hasko G, Xu DZ. A study of the biologic activity of trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph over time and the relative role of cytokines. Surgery. 2004;136:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams CJ, Jr, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Factors larger than lOOkD in post- hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph are toxic for endothelial cells. Surgery. 2001;129:351–362. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.111698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glenn TM, Lefer AM. Protective effect of thoracic lymph diversion in hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1970;219:1305–1310. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.5.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baxter CR, Cook WA, Shires GT. Serum myocardial depressant factor of burn shock. Surg Forum. 1966;17:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santis DD, Phillips P, Spath M, Lefer AM. Delayed appearance of a circulating myocardial depressant factor in burn patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:22–24. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(81)80454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White DJ, Maass DL, Sanders B, Morton JW. Cardiomyocyte intracellular calcium and cardiac dysfunction after burn trauma. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:14–22. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto S, Kuntzweiler TA, Wallick ET, Sperelakis N, Yatani A. Amino acid substitutions in the rat Na+, K(+)-ATPase alpha 2-subunit alter the cation regulation of pump current expressed in HeLa cells. J Physiol. 1996;495:733–742. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun J, Picht E, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Hypercontractile female hearts exhibit increased S-nitrosylation of the L-type Ca2+ channel α1 subunit and reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2006;98:403–411. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202707.79018.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senthil M, Watkins A, Barlos D, Xu D, Lu Q, Abungu B, Caputo F, Feinman R, Deitch EA. Intravenous injection of trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph causes lung injury that is dependent upon activation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway. Ann Surg. 2007;246:822–830. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deitch EA. Animal models of sepsis and shock: A review and lessons learned. Shock. 1998;9:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baue AE. Multiple organ failure, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Why no magic bullet? Arch Surg. 1997;132:703–707. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430310017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baue AE. Multpile organ failure – the discrepancy between our scientific knowledge and understanding and the management our patients. Lagenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385:441–453. doi: 10.1007/s004230000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]