Abstract

Objective

NF-κB activation is associated with several inflammatory disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), making this family of transcription factors a good target for the development of antiinflammatory treatments. Although inhibitors of the NF-κB pathway are currently available, their specificity has not been adequately determined. IκBα is a physiologic inhibitor of NF-κB and a potent repressor experimentally when expressed in a nondegradable form. We describe here a novel means for specifically regulating NF-κB activity in vivo by administering a chimeric molecule comprising the super-repressor IκBα (srIκBα) fused to the membrane-transducing domain of the human immunodeficiency virus Tat protein (Tat-srIκBα).

Methods

The Wistar rat carrageenan-induced pleurisy model was used to assess the effects of in vivo administration of Tat-srIκBα on leukocyte infiltration and on cytokine and chemokine production.

Results

Systemic administration of Tat-srIκBα diminished infiltration of leukocytes into the site of inflammation. Analysis of the recruited inflammatory cells confirmed uptake of the inhibitor and reduction of the NF-κB activity. These cells exhibited elevated caspase activity, suggesting that NF-κB is required for the survival of leukocytes at sites of inflammation. Analysis of exudates, while showing decreases in the production of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-1β, also revealed a significant increase in the production of the neutrophil chemoattractants cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant 1 (CINC-1) and CINC-3 compared with controls. This result could reveal a previously unknown feedback mechanism in which infiltrating leukocytes may down-regulate local production of these chemokines.

Conclusion

These results provide new insights into the etiology of inflammation and establish a strategy for developing novel therapeutics by regulating the signaling activity of pathways known to function in RA.

NF-κB is a blanket term referring to homodimers and heterodimers of a subset of the Rel family of transcription factors (1,2). Five members of the NF-κB family have been identified in mammals: RelA (p65), RelB, and c-Rel, which contain transactivation domains, and p50 and p52, which are expressed as precursor proteins p105 (NF-κB1) and p100 (NF-κB2), respectively. The p50/p65 dimer is the most common form found in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells, where it is usually bound to the α- or β-isoform of the inhibitor of κB (IκBα or IκBβ) via ankyrin repeats (3). Stimulation of the cell by a number of different sources (e.g., tumor necrosis factor α [TNFα], interleukin-1β [IL-1β], oxidative stress, and lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) leads to activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Activated IKK phosphorylates IκBα at Ser32 and Ser36 (or the respective serine residues on IκBα), which causes its polyubiquitination and 26S proteasomic degradation (4). Disruption of the NF-κB/IκBα complex results in the inactivation of a nuclear export signal and the accumulation of NF-κB in the nucleus (5), where it initiates gene transcription. A large number of different genes with NF-κB–binding domains in their promoters have been identified, including several proinflammatory genes (6,7).

NF-κB activation is associated with many chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, and atherosclerosis (1,2). Immunohistochemical analysis of synovium from RA patients detected nuclear localization of NF-κB, which is indicative of its activation (8,9). Experiments in cultured rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts demonstrated constitutive activation of NF-κB that was further augmented by addition of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β or TNFα (10,11). Importantly, expression of a dominant-negative mutant of the IKKβ subunit of the IKK complex blocked the activation of NF-κB and the release of cytokines from these cells (12). The involvement of NF-κB in inflammatory joint disease has been also corroborated by studies in animal models, in which inhibition of NF-κB activity strongly reduced the severity of arthritis (13).

The involvement of NF-κB in inflammatory diseases and the large number of proinflammatory mediators regulated by this transcription factor makes this molecule an attractive target for antiinflammatory treatments (7,14). Agents currently used to inhibit NF-κB signaling are small compounds that inhibit proteasome function and therefore IκBα degradation, decoy oligonucleotides, peptides that interfere with the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and, recently, small compounds that inhibit the enzymatic activity of the IKKβ subunit (14-16). However, the specificity of some of these compounds has not been conclusively determined, and the in vivo use of other biologic inhibitors may be hampered owing to the drawbacks of the currently available delivery vectors.

We recently described a novel way of regulating NF-κB activity in vitro by combining the protein-transducing domain (PTD) of the human immunodeficiency virus Tat protein with the super-repressor IκBα (Tat-srIκBα) (17). The Tat PTD, in common with similar domains found in VP22 from herpes simplex virus (18) and Antennapedia from Drosophila (19), is a region rich in positively charged amino acids that are thought to interact with negatively charged phospholipids in mammalian plasma membranes. This interaction facilitates entry of the protein into the cell. The srIκBα is a mutant form of IκBα in which Ser32 and Ser36 have been substituted for alanines. Because it cannot be phosphorylated by IKK, srIκBα binds irreversibly to NF-κB (20,21). Previous studies have shown that proteins fused to Tat PTD are carried inside cells when added exogenously, and furthermore, these “cargo” proteins retain their biologic activity within the cell (22-25). Tat-srIκBα fusion protein was capable of entering Jurkat T cells and HeLa cells in vitro, and could be coimmunoprecipitated with p65. Furthermore, it prevented TNFα- and IL-1β–induced NF-κB–mediated transcription, demonstrating that the srIκBα portion retained its biologic function within the cell (17).

Here we describe the in vivo effects of Tat-srIκBα in the rat carrageenan-induced pleurisy model, a well-characterized model of inflammation that has previously been used for the development of antiinflammatory and antirheumatic drugs (26). Following intrapleural injection with carrageenan, proinflammatory mediators are released, and the pleural cavity fills with edematous fluid (27). In the early phase, neutrophils are the predominant infiltrating cell type, peaking in numbers at ∼6 hours; the neutrophils are later replaced by macrophages and lymphocytes (28). NF-κB activation has been demonstrated in cells recovered from pleurisy exudates at both early and late time points (28,29). We show here that Tat-srIκBα, when administered intravenously in the early phase, can inhibit neutrophil recruitment to the pleural cavity and can modulate local production of cytokines and chemokines. This inhibition was associated with enhanced apoptosis of cells entering the pleural cavity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of Tat fusion proteins

Purification of fusion proteins was performed as previously described (23), with some modifications. BL21(DE3)pLysS bacteria (Novagen, Madison, WI) transformed with Tat-srIκBα– or (Tat-β-gal)–expressing constructs were grown to an optical density of 0.5 in Luria-Bertani/ampicillin medium, and cultures were induced for 3 hours with 1 mM IPTG (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK). Bacterial pellets were resuspended in buffer Z (8M urea, 100 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0) containing 15 mM imidazole and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (5 μg/ml each of pepstatin A, chymostatin, and leupeptin, 50 μg/ml of 4-[2-aminoethyl]benzenesulfonyl fluoride, and 50 units/ml of aprotinin; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), at 5 ml/gm of wet weight. Lysates were rotated at room temperature for 1 hour and clarified by centrifugation at 12,000g for 30 minutes at room temperature. One milliliter of 50% Ni2+-agarose (Qiagen, Crawley, UK)/phosphate buffered saline (PBS) slurry was added to every 4 ml of lysate, and incubation was carried out for 1 hour at room temperature. The beads were washed extensively with buffer Z containing 15 mM imidazole, and bound material was eluted with buffer Z containing 1M imidazole.

Eluted proteins were dialyzed extensively against PBS at 4°C or desalted in PD-10 columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK), aliquotted, and stored at −70°C. Protein concentration was determined with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

For some experiments, Tat-IκBα and Tat-β-gal proteins were labeled with N-hydroxysuccinimide–fluorescein (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions, while bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich), labeled in an identical manner, was used as a control.

Tat fusion protein administration and carrageenan-induced pleurisy

Male Wistar rats (Tuck and Sons, Battlesbridge, UK) with a mean ± SD body weight of 150 ± 20 gm were injected intravenously with 200 μg of Tat-β-gal or Tat-srIκBα in PBS or with 200 μl of PBS alone (10 animals/group). After 30 minutes, 0.15 ml of 1% (weight/volume) λ-carrageenan (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the pleural cavity of all rats, and inflammatory exudates were collected 6 hours later, as previously described (26). All animal experimentation was done according to the regulations for the care and use of animals.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSAs were performed as previously described (29). Briefly, cells recovered from pleural exudates were disrupted in lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 350 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 20% (volume/volume) glycerol, 0.6% (v/v) Nonidet P40, and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Also included was a cocktail of protease inhibitors containing 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml each of leupeptin, chymostatin, and pepstatin A, and 0.5 μg/ml of aprotinin (all from Calbiochem). NF-κB consensus (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) oligonucleotide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was end-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega, Southampton, UK) using γ32P-ATP (ICN Biochemicals, Oxfordshire, UK) as substrate.

Binding reactions were carried out for 30 minutes on ice in a 20-μl final volume using 20 μg of protein extract in binding buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 0.5 μg of poly[dI-dC] [Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK], 2% [v/v] Ficoll, and 2.5% glycerol [v/v]). Specificity of binding for NF-κB species was determined by competition with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled NF-κB consensus and mutant (5′-AGTTGAGGCGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotide/protein complexes were visualized following electrophoresis of binding reactions on 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and autoradiography.

Caspase 3 assay

Caspase 3 activity in cells collected from pleural exudates was assessed in duplicate using the Apo-ONE assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were treated with the caspase substrate Z-DEVD-R110 (Biotium, Hayward, CA) in lysis buffer, and caspase 3 activity was monitored according to the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine released from the substrate using a Tecan GENios (Jencons, UK) detector over a time period of 18 hours. The values obtained at the 18-hour time point following substrate addition are reported.

Cytokine and chemokine assays

TNFα, IL-1β, cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant 1 (CINC-1), and CINC-3 were assayed in cell-free inflammatory pleural exudates using commercially available sandwich enzyme-linked immunoassay kits (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting for apoptosis-associated markers

Inflammatory cells collected from pleural exudates were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris HCl) supplemented with protease inhibitors and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and lysate aliquots representing equivalent amounts of protein were resolved by 12% or 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and probed with polyclonal antibodies to caspase 9, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), IκBα (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), or JNK-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated protein A (Amersham Biosciences). Blots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescent system (Amersham Biosciences).

Flow cytometry

Cells (1 × 106) recovered from the pleural exudates of rats given intravenous injections of PBS, Tat-β-gal, or Tat-srIκBα were stained for phosphatidylserine exposure with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled annexin V kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Positively stained (apoptotic) cells were identified by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

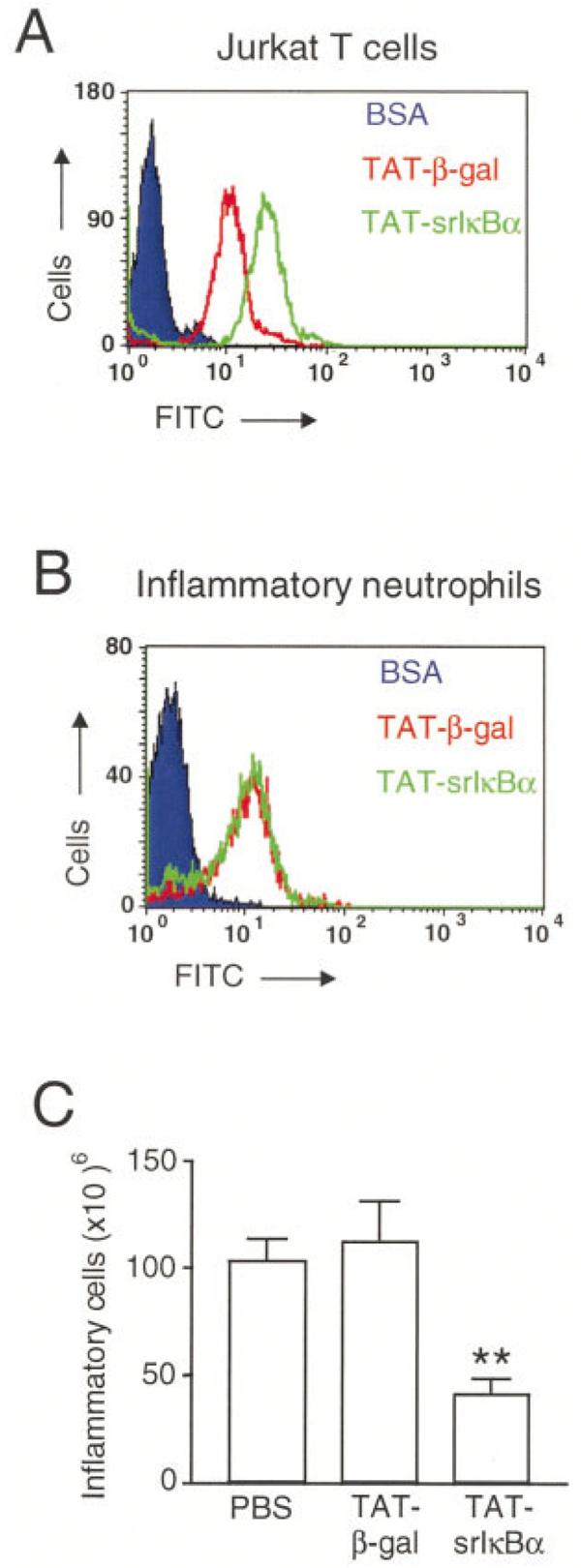

Reduced cell infiltration into the pleural cavity after systemic administration of Tat-srIκBα

To determine whether Tat fusion proteins enter cells in vitro and in vivo, we labeled Tat-srIκBα and Tat-β-gal with FITC, and conjugated proteins were either incubated with Jurkat T cells or injected intravenously into animals. FITC-labeled BSA served as control. Analysis of Jurkat T cells by flow cytometry showed uptake of Tat-srIκBα and Tat-β-gal, but not BSA (Figure 1A). In rats injected intravenously with FITC-conjugated Tat-β-gal or Tat-srIκBα, fluorescent cells could be detected in the pleural infiltrate following induction of pleurisy with carrageenan (Figure 1B). This suggests that Tat fusion proteins were entering cells in the bloodstream, which were then recruited to the pleural cavity in response to carrageenan injection. No fluorescent cells were detected in rats treated with FITC-labeled BSA.

Figure 1.

Cell uptake of Tat fusion proteins and reduced neutrophil recruitment to the pleural cavity by Tat-srIκBα. A, Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of Jurkat T cells incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated Tat-srIκBα, Tat-β-gal, or bovine serum albumin (BSA) control. B, FACS analysis of inflammatory neutrophils collected at 4 hours from rats with carrageenan-induced pleurisy after intravenous injection of FITC-conjugated Tat-srIκBα, Tat-β-gal, or BSA. C, Total number of inflammatory cells collected from 6-hour pleural exudates induced by carrageenan after systemic administration of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), Tat-β-gal, or Tat-srIκBα. Values are the mean and SEM of 10 animals per group. ** = P < 0.01 versus Tat-β-gal controls and P < 0.001 versus PBS controls.

Next, we looked at the effects of Tat-srIκBα treatment on cell numbers at the peak of the inflammatory response. When given intravenously 30 minutes prior to intrapleural carrageenan injection, 200 μg of Tat-srIκBα significantly reduced inflammatory cell recruitment to the pleural cavities of rats at 6 hours (by 59.1% versus PBS [P < 0.001] and by 61.3% versus Tat-β-gal [P < 0.01]) (Figure 1C). We have found that washing the pleural cavity of control animals that have not been challenged with carrageenan yields ∼4–6 × 106 cells, which are mostly mononuclear cells (Gilroy DW: unpublished observations).

Reduced NF-κB activity in inflammatory cells from Tat-srIκBα–treated animals

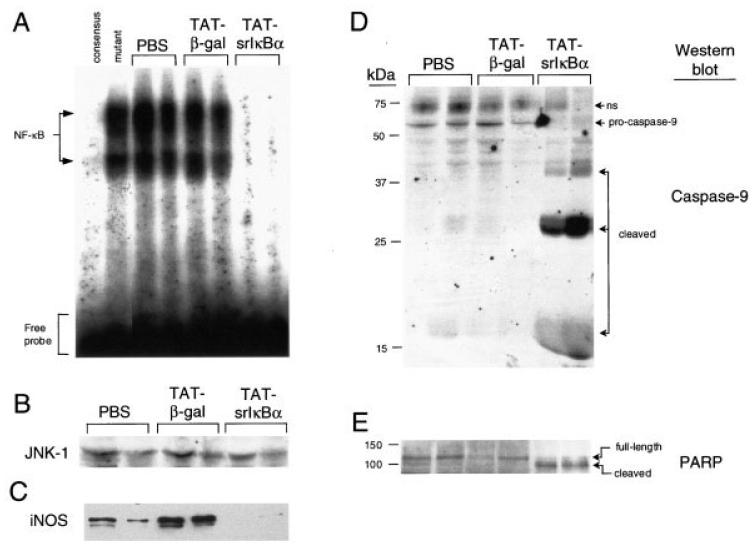

To determine if the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB in cells infiltrating the pleural cavity was inhibited by Tat-srIκBα, we analyzed by EMSA cell lysates representing equivalent amounts of protein. DNA-binding activity was readily detected in inflammatory cell lysates from rats treated with PBS or Tat-β-gal, but was strongly reduced in cells recovered from rats treated with Tat-srIκBα (Figure 2A). Competition experiments using unlabeled consensus or mutant κB oligonucleotides indicated the presence of 2 different NF-κB complexes, both of which were inhibited by Tat-srIκBα. These complexes represent p50/p65 heterodimers and p50/p50 homodimers (29,30). Western blot analysis of similar aliquots of these cell lysates using anti–JNK-1 antibodies was used as loading control (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Reduced NF-κB activity, but elevated caspase activation, in inflammatory neutrophils from Tat-srIκBα–treated animals. A, DNA-binding activity of NF-κB in cell lysates of infiltrating neutrophils obtained from 6-hour pleural exudates following systemic administration of Tat fusion proteins or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) vehicle. Results from 2 animals from each treatment group are shown. Protein/oligonucleotide complexes specific for NF-κB were determined by competition with unlabeled NF-κB consensus or mutant oligonucleotides, using inflammatory cell lysates from PBS-treated animals. Protein concentrations in cell lysates were quantified with the bicinchoninic acid kit. B, Western blotting with anti–JNK-1 antibodies (loading control). Similar aliquots from these lysates were probed with antibodies to C, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) to determine the expression of NF-κB-regulated genes, and with antibodies to D, caspase-9 and E, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) to detect caspase-mediated cleavage of protein substrates. Full-length proteins and their cleaved products are indicated; ns = nonspecific.

To determine whether the reduction in DNA binding activity was reflected in a reduced transcription of NF-κB–responsive genes, the cell lysates were analyzed for expression of iNOS protein, which is up-regulated at 6 hours (27). Although some variability in iNOS expression was noticed among different animals in the same group, overall there was clear inhibition of iNOS expression in infiltrating cells collected from Tat-srIκBα–treated rats, mirroring the reduction observed in the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB (Figure 2C).

Elevated caspase activity in inflammatory cells from Tat-srIκBα–treated animals

Because NF-κB signaling can be antiapoptotic (31-33), we assessed apoptosis as a possible cause of the reduction in recruited cell numbers in Tat-srIκBα–treated rats. Apoptosis is associated with the cascading activation of a series of caspases, of which caspase 9 is one of the first (34). Caspase 9 was activated in lysates from rats treated with Tat-srIκBα, as indicated by the absence of inactive 51-kd procaspase 9 and the presence of the active 38-kd form and 17-kd cleaved product (Figure 2D). Additional cleaved products migrating at ∼25–27 kd were also observed, possibly indicating an alternative cleavage site for caspase 9 in neutrophils. In rats treated with PBS or Tat-β-gal, the 51-kd procaspase 9 was the predominant band, with only weak signals detected for the 38-kd, 25–27-kd, and 17-kd cleaved products (Figure 2D).

Caspase 9 activates caspase 3, which, in turn, cleaves a number of different substrates in the cytoplasm, including PARP (35). PARP is a 116-kd DNA repair enzyme that is indispensable in maintaining cell viability, and the cleavage of PARP is a defining characteristic of apoptosis (36). In rats treated with PBS or Tat-β-gal, the full-length 116-kd PARP was detected (Figure 2E). However, in rats treated with Tat-srIκBα, the 116-kd molecule was strongly reduced and replaced with the cleaved, disabled 89-kd fragment.

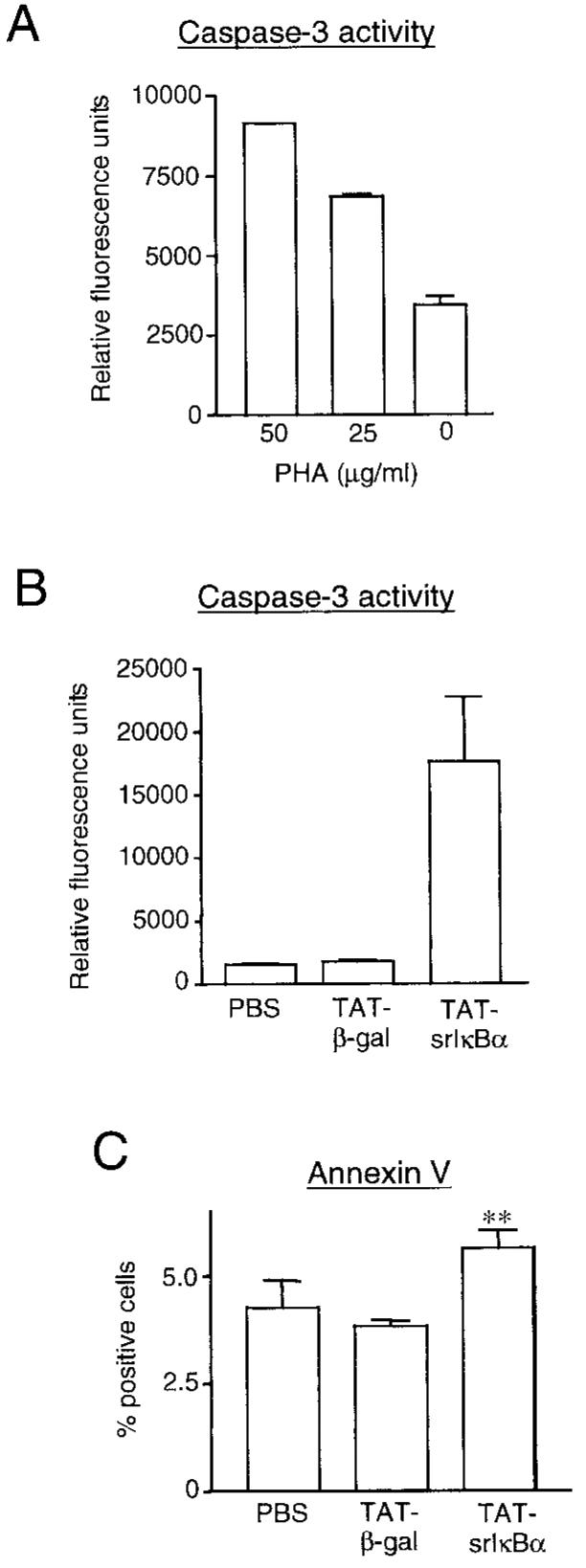

To directly assess caspase 3 activity in inflammatory cell lysates, a fluorescence-based method was established first in Jurkat T cells stimulated with phytohemagglutinin, a lectin known to induce apoptosis in this cell line (Figure 3A). This method revealed an increase in caspase 3 activity in inflammatory cell lysates from Tat-srIκBα–treated animals compared with Tat-β-gal– and PBS-treated littermates (Figure 3B). We also stained inflammatory cells isolated from 6-hour pleurisy exudates with annexin V, which binds to phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic cells. This method has been previously used in this in vivo model to determine the magnitude and kinetics of inflammatory cell apoptosis (37). A significant increase in annexin V binding was detected in inflammatory cells from Tat-srIκBα–treated animals compared with PBS- and Tat-β-gal–treated cohorts (Figure 3C). As was shown in a recent study, over the time course of the inflammatory response, such differences in annexin V binding represent a significant shift toward apoptosis (37). Taken together, these results suggest that inhibition of NF-κB in infiltrating neutrophils by Tat-srIκBα administration accelerates apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Increased apoptosis of infiltrating leukocytes in Tat-srIκBα–treated animals. A, Jurkat T cells (1 × 105) were treated for 16 hours with the indicated concentrations of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and analyzed for caspase 3 activity using a specific rhodamine-labeled substrate. Values are the mean and SEM of duplicate measurements. B, Caspase 3 activity detected in 1 × 106 cells from each pleural exudate obtained from animals treated intravenously with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or Tat fusion proteins. Shown are the cumulative data collected from 3–4 animals from each treatment group, with each sample analyzed in duplicate. C, Inflammatory cells from animals treated with PBS or Tat fusion proteins were analyzed for annexin V binding immediately after collection from the pleural cavity. Shown are the cumulative data from 5 animals from each treatment group. All values are the mean and SEM. ** = P < 0.01 versus Tat-β-gal and PBS controls.

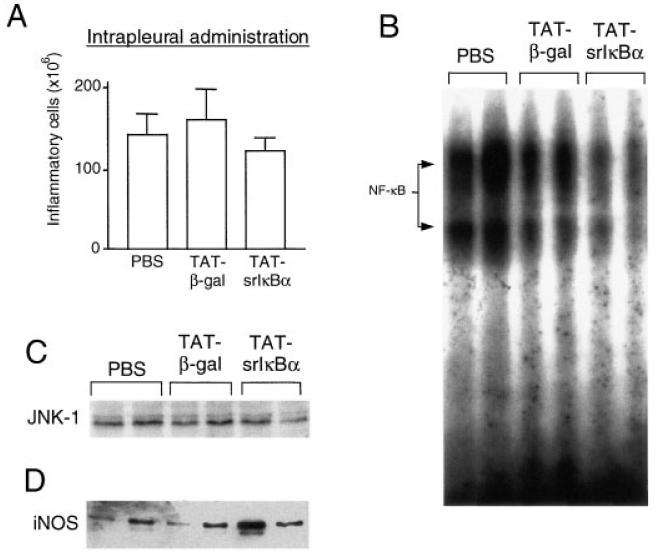

Reduced potency of locally administered Tat-srIκBα in inhibiting cell infiltration

We also examined the effects of Tat-srIκBα when administered intrapleurally 30 minutes prior to carrageenan injection. A small reduction in the numbers of recruited cells was observed; however, the difference was not significant compared with the PBS group or the Tat-β-gal group (Figure 4A). Analysis of cell lysates showed some reduction in NF-κB DNA-binding activity in inflammatory cells from the Tat-srIκBα–treated group (Figure 4B); however, this was not significant enough to inhibit transcription of iNOS (Figure 4D). Western blot analysis of lysates with anti–JNK-1 antibodies was used as loading control (Figure 4C). Thus, the potency with which Tat-srIκBα inhibits NF-κB activity and migration of neutrophils into the inflamed site depends on its route of administration.

Figure 4.

NF-κB activity and cell recruitment following intrapleural administration of Tat-srIκBα. A, Total number of cells infiltrating the pleural cavity of animals injected intrapleurally with 200 μg of the indicated Tat fusion proteins or with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) control 30 minutes before the induction of pleurisy. Values are the mean and SEM. The DNA-binding activity of B, NF-κB and C, JNK-1 and the expression of D, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in inflammatory cell lysates from animals treated locally with Tat fusion proteins were determined by Western blotting.

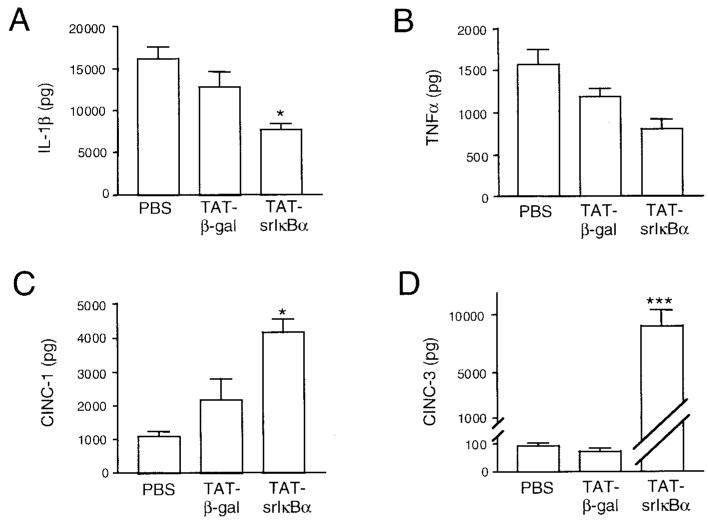

Changes in local production of cytokines and chemokines in Tat-srIκBα–treated animals

Key cytokines are associated with the development of inflammatory responses. We examined total levels of IL-1β and TNFα in 6-hour pleural exudates from rats treated with PBS or Tat fusion proteins. There was a reduction in the levels of IL-1β and TNFα in exudates from the Tat-srIκBα–treated group (Figures 5A and B, respectively), which, in the case of IL-1β, were significantly lower compared with the Tat-β-gal–treated control group. Because NF-κB activity is involved in the production of both IL-1β and TNFα, this result may suggest that intravenously administered Tat-srIκBα does not accumulate in sufficient concentration in the pleural cavity to completely block the production of TNFα and IL-1β and possibly other NF-κB–regulated mediators. Alternatively, other transcription factors, which are not inhibited by the Tat-srIκBα repressor, may contribute to the transcriptional control of these genes (38,39).

Figure 5.

Changes in cytokine and chemokine production in animals treated with the Tat-srIκBα repressor. Cell-free exudates collected from 6-hour pleural exudates were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the presence of the proinflammatory cytokines A, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (* = P < 0.05 versus TAT-β-gal group) and B, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), as well as for C, cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant 1 (CINC-1) (* = P < 0.05 versus TAT-β-gal control and P < 0.0001 versus phosphate buffered saline [PBS] control) and D, CINC-3 (*** = P < 0.0001 versus TAT-β-gal and PBS controls). Values are the mean and SEM total protein present in the exudates.

We also evaluated levels of CINC-1 (the rat homolog of human GROα) (40), and CINC-3 (also known as macrophage inflammatory protein 2) (41). CINC-1 is produced in zymosan-induced pleurisy (42) and following intrapleural injections of TNFα (43); however, no data are available on CINC-3 production in this model. Surprisingly, the levels of CINC-1 in Tat-srIκBα–treated rats were significantly elevated above the levels in the PBS-treated (P < 0.0001) and Tat-β-gal–treated (P < 0.05) groups (Figure 5C). A more dramatic difference was seen for CINC-3 production, where levels in the Tat-srIκBα–treated group were elevated by more than 100-fold compared with the levels in the control groups (P < 0.0001) (Figure 5D).

DISCUSSION

The NF-κB signaling pathway has emerged as a key mediator of inflammation and therefore represents a target for the treatment of inflammatory disorders (14,16). In RA, synovial fibroblasts cultured in vitro in the presence of TNFα underwent apoptosis when srIκB mutant was expressed by means of an adenovirus vector (44), suggesting that NF-κB plays a critical role in supporting the survival of this cell type in RA joints. That the hyperplasia in RA joint is NF-κB driven has been suggested by other studies (45). Also, the production of TNFα by macrophages, a critical cell type that controls aspects of inflammation in RA joints, was shown to be dependent on NF-κB activity (46).

An increasing number of inhibitors are currently being developed that block the NF-κB signaling pathway at various steps. Compounds that inhibit proteasome function, and therefore IκBα degradation, are used in experimental settings to assess involvement of NF-κB (15). However, because such inhibitors would be expected to block the physiologic turnover of unrelated proteins as well, nonspecific effects will most likely be a serious drawback for their use in the clinic. Use of decoy oligonucleotides to block DNA binding of NF-κB and RNA interference technology to modulate the expression of genes that participate in the NF-κB pathway (i.e., IKKβ) could be more specific than proteasome inhibitors (14,47). Their use, however, could be limited because of the need for safe and efficient delivery systems, and although virus vectors are able to achieve such expression, they also have the potential to induce NF-κB activation, hence curtailing the effects of the inhibitor and complicating the interpretation of the results. Another class of recently developed small-molecule inhibitors blocks NF-κB activation by inhibiting the IKKβ subunit of the IKK complex (16). As is the case for other kinase inhibitors, their specificity for IKKβ has to be demonstrated before they can be used as antiinflammatory drugs.

To directly and specifically inhibit NF-κB action, we previously constructed a membrane-penetrating form of the super-repressor IκBα, Tat-srIκBα, and showed that, when added exogenously to cells in culture, the repressor was able to inhibit the biologic activity of NF-κB (17). Here, we extended our studies by investigating the effects of the Tat-srIκBα chimera in an in vivo model of inflammation. When injected intravenously shortly before administration of the inflammatory stimulus, Tat-srIκBα reduced the number of leukocytes migrating from the bloodstream to the site of inflammation. In addition, inflammatory cells recovered from the pleural cavity of Tat-srIκBα–treated animals displayed elevated caspase activity compared with those from controls, suggesting that, in addition to their reduced migratory response, these cells were more prone to apoptosis. These results are consistent with studies that demonstrate activation and a prosurvival role for NF-κB in neutrophils following stimulation of the cells with proinflammatory cytokines or type I interferon (30,48).

Accelerated apoptosis is one possible mechanism through which Tat-srIκBα reduces neutrophil numbers in the pleural cavity when given intravenously. Neutrophils that take up the inhibitor in the bloodstream and are then exposed to proinflammatory stimuli are prone to apoptosis because of their inability to activate NF-κB and, hence, are less capable of transmigration. Alternatively, because adhesion molecule promoters contain NF-κB–binding domains (E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 [49]), it is possible that failure to up-regulate the expression of such molecules on vascular endothelial cells may contribute to the decrease in the number of cells that accumulate at sites of inflammation. Consistent with this model, it was recently demonstrated that NF-κB action in cells of nonhematopoietic origin is important for leukocyte recruitment during LPS-induced pneumonia (50).

In contrast to the effects of systemic administration, when the Tat-srIκBα inhibitor was delivered locally, only a marginal reduction in neutrophil migration was observed following induction of inflammation. Therefore, the route of administration can determine the potency of inhibition in this in vivo model. A plausible explanation for this difference is that when administered intravenously, Tat-srIκBα is taken up by circulating cells, blocking the activity of NF-κB possibly before the cells are exposed to stimuli generated by the intrapleural injection of carrageenan. In contrast, when Tat-srIκBα is administered intrapleurally, neutrophils are most likely exposed to significant doses of the inhibitor after they are activated and induced to migrate into the pleural cavity.

As expected, production of the key proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β was reduced in pleural exudates from Tat-srIκBβ–treated animals, although it was not completely abolished. Lack of complete inhibition could be due to the action of regulatory transcription factors other than NF-κB, as has been reported for the IL-1β genes, for which it was shown that NF-κB is only a component that can amplify a core inducible activity regulated by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (NF-IL6) (38,39). Therefore, complete inhibition of transcription of certain proinflammatory cytokines in vivo may depend upon targeting other transcription factors as well.

Surprisingly, the concentrations of the neutrophil chemoattractants CINC-1 and CINC-3 were strongly increased. Over the course of these experiments, we noticed that exudates with the lowest number of infiltrating cells contained the highest levels of CINC-3. This may indicate that inflammatory neutrophils that infiltrate the site of inflammation are able to down-regulate the production of CINC-1 and CINC-3, and possibly other mediators, by resident cells. This type of down-regulation could represent a feedback mechanism that prevents continuous infiltration of cells. Similar observations in a model of murine LPS-induced neutrophil recruitment to bronchoalveolar spaces have been reported (51). Therefore, membrane-permeable inhibitors of signaling cascades delivered in vivo may be useful tools for uncovering novel biologic mechanisms.

In summary, our results demonstrate the importance of NF-κB in neutrophil migration and survival during inflammation and establish a methodology that can be applied to regulate signaling pathways in vivo. This methodology opens the way for the development of a new type of antiinflammatory agent that can be used in RA and other inflammatory disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steve Ley and Yuti Chernajovsky for critically reading the manuscript.

Supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Joint Research Board of the Special Trustees of St. Bartholomew's Hospital. Dr. Kabouridis is recipient of a Wellcome Trust Career Development award (no. 58408).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin AS. The transcription factor NF-κB and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:3–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin AS., Jr. The NF-κB and IκB proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Ann Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birbach A, Gold P, Binder BR, Hofer E, de Martin R, Schmid JA. Signaling molecules of the NF-κB pathway shuttle constitutively between cytoplasm and nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10842–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:135–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI11914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roshak AK, Callahan JF, Blake SM. Small-molecule inhibitors of NF-κB for the treatment of inflammatory joint disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:316–21. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handel ML, McMorrow LB, Gravallese EM. Nuclear factor–κB in rheumatoid synovium: localization of p50 and p65. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1762–70. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marok R, Winyard PG, Coumbe A, Kus ML, Gaffney K, Blades S, et al. Activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor–κB in human inflamed synovial tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:583–91. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujisawa K, Aono H, Hasunuma T, Yamamoto K, Mita S, Nishioka K. Activation of transcription factor NF-κB in human synovial cells in response to tumor necrosis factor α. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:197–203. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roshak AK, Jackson JR, McGough K, Chabot-Fletcher M, Mochan E, Marshall LA. Manipulation of distinct NFκB proteins alters interleukin-1β-induced human rheumatoid synovial fibroblast prostaglandin E2 formation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31496–501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aupperle KR, Bennett BL, Boyle DL, Tak PP, Manning AM, Firestein GS. NF-κB regulation by IκB kinase in primary fibroblast-like synoviocytes. J Immunol. 1999;163:427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tak PP, Gerlag DM, Aupperle KR, van de Geest DA, Overbeek M, Bennett BL, et al. Inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase β is a key regulator of synovial inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1897–907. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1897::AID-ART328>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makarov SS. NF-κB as a therapeutic target in chronic inflammation: recent advances. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:441–8. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott PJ, Zollner TM, Boehncke WH. Proteasome inhibition: a new anti-inflammatory strategy. J Mol Med. 2003;81:235–45. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karin M, Yamamoto Y, Wang QM. The IKK NF-κB system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:17–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabouridis PS, Hasan M, Newson J, Gilroy DW, Lawrence T. Inhibition of NF-κB activity by a membrane-transducing mutant of IκBα. J Immunol. 2002;169:2587–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott G, O'Hare P. Intercellular trafficking and protein delivery by a herpesvirus structural protein. Cell. 1997;88:223–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81843-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A. The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10444–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traenckner EB, Pahl HL, Henkel T, Schmidt KN, Wilk S, Baeuerle PA. Phosphorylation of human IκB-α on serines 32 and 36 controls IκB-α proteolysis and NF-κB activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 1995;14:2876–83. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiDonato J, Mercurio F, Rosette C, Wu-Li J, Suyang H, Ghosh S, et al. Mapping of the inducible IκB phosphorylation sites that signal its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1295–304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fawell S, Seery J, Daikh Y, Moore C, Chen LL, Pepinsky B, et al. Tat-mediated delivery of heterologous proteins into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:664–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagahara H, Vocero AA, Snyder EL, Ho A, Latham DG, Lissy NA, et al. Transduction of full-length TAT fusion proteins into mammalian cells: TAT-p27Kip1 induces cell migration. Nat Med. 1998;4:1449–52. doi: 10.1038/4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero AA, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science. 1999;285:1569–72. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabouridis PS. Biological applications of protein transduction technology. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willis D, Chivers J, Paul-Clark MJ, Willoughby DA. Inducible cyclooxygenase may have anti-inflammatory properties. Nat Med. 1999;5:698–701. doi: 10.1038/9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomlinson A, Appleton I, Moore AR, Gilroy DW, Willis D, Mitchell JA, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase and nitric oxide synthase isoforms in rat carrageenin-induced pleurisy. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:693–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Acquisto F, Ianaro A, Ialenti A, Iuvone T, Colantuoni V, Carnuccio R. Activation of nuclear transcription factor κB in rat carrageenin-induced pleurisy. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;369:233–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence T, Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, Willoughby DA. Possible new role for NF-κB in the resolution of inflammation. Nature Med. 2001;7:1291–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro-Alcaraz S, Miskolci V, Kalasapudi B, Davidson D, Vancurova I. NF-κB regulation in human neutrophils by nuclear IκBα: correlation to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:3947–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr. NF-κB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–3. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Smaele E, Zazzeroni F, Papa S, Nguyen DU, Jin R, Jones J, et al. Induction of gadd45β by NF-κB downregulates pro-apoptotic JNK signalling. Nature. 2001;414:308–13. doi: 10.1038/35104560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang F, Tang G, Xiang J, Dai Q, Rosner MR, Lin A. The absence of NF-κB-mediated inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation contributes to tumor necrosis factor α-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8571–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8571-8579.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholson DW. Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1028–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tewari M, Quan LT, O'Rourke K, Desnoyers S, Zeng Z, Beidler DR, et al. Yama/CPP32 β, a mammalian homolog of CED-3, is a CrmA-inhibitable protease that cleaves the death substrate poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cell. 1995;81:801–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pieper AA, Verma A, Zhang J, Snyder SH. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, nitric oxide and cell death. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:171–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilroy DW, Colville-Nash PR, McMaster S, Sawatzky DA, Willoughby DA, Lawrence T. Inducible cyclooxygenase-derived 15-deoxy-Δ12-14-PGJ2 brings about acute inflammatory resolution in rat pleurisy by inducing neutrophil and macrophage apoptosis. FASEB J. 2003;17:2269–71. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1162fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsukada J, Saito K, Waterman WR, Webb AC, Auron PE. Transcription factors NF-IL6 and CREB recognize a common essential site in the human prointerleukin 1β gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7285–97. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldassare JJ, Bi Y, Bellone CJ. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in IL-1β transcription. J Immunol. 1999;162:5367–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe K, Konishi K, Fujioka M, Kinoshita S, Nakagawa H. The neutrophil chemoattractant produced by the rat kidney epithelioid cell line NRK-52E is a protein related to the KC/gro protein. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19559–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakagawa H, Komorita N, Shibata F, Ikesue A, Konishi K, Fujioka M, et al. Identification of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractants (CINC), rat GRO/CINC-2α and CINC-2β, produced by granulation tissue in culture: purification, complete amino acid sequences and characterization. Biochem J. 1994;301:545–50. doi: 10.1042/bj3010545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Utsunomiya I, Ito M, Oh-ishi S. Generation of inflammatory cytokines in zymosan-induced pleurisy in rats: TNF induces IL-6 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC) in vivo. Cytokine. 1998;10:956–63. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Utsunomiya I, Ito M, Watanabe K, Tsurufuji S, Matsushima K, Oh S. Infiltration of neutrophils by intrapleural injection of tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-1, and interleukin-8 in rats, and its modification by actinomycin D. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:611–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang HG, Huang N, Liu D, Bilbao L, Zhang X, Yang P, et al. Gene therapy that inhibits nuclear translocation of nuclear factor κB results in tumor necrosis factor α–induced apoptosis of human synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1094–105. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1094::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miagkov AV, Kovalenko DV, Brown CE, Didsbury JR, Cogswell JP, Stimpson SA, et al. NF-κB activation provides the potential link between inflammation and hyperplasia in the arthritic joint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Georganas C, Liu H, Perlman H, Hoffmann A, Thimmapaya B, Pope RM. Regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts: the dominant role for NF-κB but not C/EBPβ or c-Jun. J Immunol. 2000;165:7199–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takaesu G, Surabhi RM, Park KJ, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Gaynor RB. TAK1 is critical for IκB kinase-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:105–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang K, Scheel-Toellner D, Wong SH, Craddock R, Caamano J, Akbar AN, et al. Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by type 1 IFN depends on cross-talk between phosphoinositol 3-kinase, protein kinase C-δ, and NF-κB signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2003;171:1035–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins T, Read MA, Neish AS, Whitley MZ, Thanos D, Maniatis T. Transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules: NF-κB and cytokine-inducible enhancers. FASEB J. 1995;9:899–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alcamo E, Mizgerd JP, Horwitz BH, Bronson R, Beg AA, Scott M, et al. Targeted mutation of TNF receptor I rescues the RelA-deficient mouse and reveals a critical role for NF-κB in leukocyte recruitment. J Immunol. 2001;167:1592–600. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmes MC, Zhang P, Nelson S, Summer WR, Bagby GJ. Neutrophil modulation of the pulmonary chemokine response to lipopolysaccharide. Shock. 2002;18:555–60. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]