Abstract

To determine the mechanisms of spermatogenesis, it is essential to identify and characterize germ cell-specific genes. Here we describe a protein encoded by a novel germ cell-specific gene, Mm.290718/ZFP541, identified from the mouse spermatocyte UniGene library. The protein contains specific motifs and domains potentially involved in DNA binding and chromatin reorganization. An antibody against Mm.290718/ZFP541 revealed the existence of the protein in testicular spermatogenic cells (159 kDa) but not testicular and mature sperm. Immunostaining analysis of cells at various stages of spermatogenesis consistently showed that the protein is present in spermatocytes and round spermatids only. Transfection assays and immunofluorescence studies indicate that the protein is localized specifically in the nucleus. Proteomic analyses performed to explore the functional characteristics of Mm.290718/ZFP541 showed that the protein forms a unique complex. Other major components of the complex included histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and heat-shock protein A2. Disappearance of Mm.290718/ZFP541 was highly correlated with hyperacetylation in spermatids during spermatogenesis, and specific domains of the protein were involved in the regulation of interactions and nuclear localization of HDAC1. Furthermore, we found that premature hyperacetylation, induced by an HDAC inhibitor, is associated with an alteration in the integrity of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in spermatogenic cells. Our results collectively suggest that the Mm.290718/ZFP541 complex is implicated in chromatin remodeling during spermatogenesis, and we provide further information on the previously unknown molecular mechanism. Consequently, we re-designate Mm.290718/ZFP541 as “SHIP1” representing spermatogenic cell HDAC-interacting protein 1.

During spermatogenesis, primary spermatocytes undergo meiotic division to produce spermatids. Early round spermatids undergo differentiation through elongation and condensation to develop into spermatozoa, a process termed spermiogenesis. Major events during this post-meiotic phase of male germ cell development include nuclear condensation and morphogenesis. In particular, spermatid chromatin undergoes reorganization to substitute histones with specific basic proteins (transition proteins). Subsequently, small arginine-rich proteins (protamines) replace transition proteins. As a result, the sperm head is condensed, and DNA is stabilized (1-3). This tightly regulated process indicates the presence of a highly organized, intrinsic genetic program involving genes unique to germ cells.

Previously, we investigated mouse spermatocyte and round spermatid UniGene libraries containing 2124 and 2155 gene-oriented transcript clusters (4, 5). Based on these studies, the proportions of germ cell-specific genes in the spermatocyte and round spermatid libraries were predicted as 11% (230 genes) and 22% (467 genes), respectively. Remarkably, more than half of these unique genes are currently unknown or uncharacterized. With the aid of systematic in silico and in vitro approaches, we narrowed the numbers down to 24 (spermatocyte UniGene study) and 28 genes (round spermatid UniGene study) exhibiting abundant transcription unique to germ cells. In silico analyses led to the prediction that a number of these genes are implicated in diverse functions, such as transcriptional regulation, nuclear integrity, cell structure, and metabolism, in spermatogenic cells. One such gene is Mm.290718 (GenBank™ accession number BC157962.1). The Mm.290718 gene encompasses a region of ∼25 kb in mouse chromosome 7. The human ortholog of Mm.290718 is in the genomic region (human chromosome 19q13.3) of conserved synteny between mouse and human. The Mm.290718 gene is composed of 12 exons, and transcribes into 4084-nucleotide mRNA encoding 1302 amino acids. The predicted molecular mass of Mm.290718 is 148 kDa.

In this study, we characterized the protein encoded by the Mm.290718 gene at the cellular and functional levels. The Mm.290718 protein is predicted to contain numerous motifs and domains potentially involved in DNA binding and chromatin reorganization. Our results show that the Mm.290718 gene encodes a nuclear protein expressed at specific stages of spermiogenesis. Proteomic analysis indicated the presence of a unique complex associated with the Mm.290718 protein. One of the major complex components was histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1).2 Further analyses suggest that the Mm.290718 complex functions in chromatin remodeling during the period of development from round to elongated spermatids. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide comprehensive information about a novel germ cell-specific protein with a potential role in the chromatin-remodeling process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Total RNA Extraction and RT-PCRs—Total RNA samples obtained from seven tissues (testis, brain, liver, spleen, kidney, skeletal muscle, and ovary) of adult mouse, cDNA from germ cell-devoid testes of W/Wv mutant mice, and prepubertal and adult male mice (aged 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, 30, and 84 days) were used for reverse transcription. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol™ Reagent (MRC) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and cDNA was synthesized by random hexamer and oligo(dT) priming with Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen). RT-PCRs were performed with primers for potassium channel tetramerization domain 19 (KCTD19) (forward, 5′-GCG GAT CCT GTA AAC AGT GGG AA-3′, and reverse, 5′-TAC TCG AGC TGC TCA GGA GCA GG-3′) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (forward, 5′-TGA AGG TCG GAG TCA ACG GAT TTG GT-3′, and reverse, 5′-CAT GTG GGC CAT GAG GTC CAC CAC-3′) as a control. Primers for the amplification of ELM2 (Egl-27 and MTA1 homology 2) and SANT (Swi3, Ada2, the co-repressor NCoR, and TFIIIB) domain-containing genes are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers for the ELM2 and SANT domain-containing genes

F indicates forward and R reverse.

| Gene | Primer direction | Primer sequence | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mta1 | F | ACTTGGAGCGTGAGGATTTC | 508-527 |

| R | CTTGTGCAGCGTGTCCATAG | 850-869 | |

| Mta2 | F | CTCCTCCAGCAATCCTTACC | 483-502 |

| R | TTGATGTCTCTGCTGCTCGG | 662-681 | |

| Mta3 | F | TTTAGTTGTAGCCCGTGCCG | 634-653 |

| R | ATTTGCTCTCGGCTTCTGCG | 1027-1046 | |

| Mier1 | F | AGCAGTAGGAATCAGAACGG | 1413-1432 |

| R | TTCCCACTGCTGTTTATCCG | 1659-1678 | |

| Mier2 | F | AAGAAACACAGTCCTCCGCT | 413-432 |

| R | AATGTCGGTTCAAGTGCAGG | 627-646 | |

| Mier3 | F | ACAGCATGGACGGAAGAGGA | 933-952 |

| R | TAAGGCTGAAGAACTGACGG | 1195-1214 | |

| Rcor1 | F | AAATGCAACGCTCGCTGGAC | 931-950 |

| R | TCGTCTTTCCCATGTTCTGC | 1114-1133 | |

| Rcor2 | F | TTGCAGAGGTGATTGGGAAC | 941-960 |

| R | ATCTTCTTCTAGGGCTGTGG | 1112-1131 | |

| Rcor3 | F | TGTATCTAACCCAGGAGGAC | 719-738 |

| R | AGGTTGTCGGTGAAGAGCAG | 1034-1053 | |

| Rere | F | AGGGATGTGTGATGGAGGCT | 1023-1042 |

| R | GCGTTTCACTTCATCCTCTG | 1190-1202 | |

| Trerf1 | F | TCAAGCTAATCCCACCCAAG | 1904-1923 |

| R | AACTTTGGCGGCGATAGGTG | 2039-2058 | |

| Mm.290718 | F | GAGAGGTGAGAAGGGTCCAG | 2196-2215 |

| R | TGCTCTTTGACTCCATCCAG | 2511-2530 |

Antibodies—PCR products corresponding to Mm.290718 and KCTD19 were generated using gene-specific primers (Mm.290718, forward, 5′-TTG GAT CCG CAC TCA AGG TGC CT-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAC TCG AGC AAG ACA GAG CCA GG-3′; KCTD19, forward, 5′-GCG GAT CCT GTA AAC AGT GGG AA-3′, and reverse, 5′-TAC TCG AGC TGC TCA GGA GCA GG-3′) incorporating 5′ BamHI and 3′ XhoI sites. Amplified products were digested with BamHI and XhoI, and ligated into the corresponding restriction sites of pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare). The resulting constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells. Each glutathione S-transferase fusion protein was affinity-purified with glutathione-Sepharose 4B. Two of the purified fusion proteins were used as antigens for producing a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Peptron). Antibodies were purified using the corresponding proteins as antigens and an AminoLink Immobilization kit (Pierce). Anti-Mm.290718, anti-KCTD19, and mouse monoclonal antibodies against acetylated lysine (Abcam) antibodies were used (2 μg/ml) for immunofluorescence. The anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma) was used (1:1000 dilution) for Western blot analysis. Anti-heat-shock protein A2 (HSPA2) (6), ADAM2, and HDAC1 (Abcam) polyclonal antibodies were used (1:1000 dilution) for Western blot analysis. Acetylated lysine (2 μg/ml) and HSPA2 (1:100) antibodies were used for immunofluorescence.

Protein Samples and Western Blot Analysis—Western blot analysis was performed using protein samples from the testes of prepubertal and adult male mice (aged 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, 30, and 84 days) as well as germ cell-devoid testes of W/Wv mutant mice. Testicular cells and sperm from testes of normal adult male mice were isolated by suspension in 52% isotonic Percoll (GE Healthcare) and centrifugation for 10 min (27,000 × g, 10 °C) and were resuspended in Mg2+-Hepes buffer (7). Sperm from the caudal epididymis and vas deferens was directly released into Mg2+-Hepes buffer. The purity of cells and sperm was evaluated by microscopy (>95%). All samples were resuspended in 5× SDS sample buffer, followed by boiling for 5 min. Samples were reduced with 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Each sample containing ∼20 μg of protein was subjected to electrophoresis on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature and hybridized for 1 h with primary antibodies. Bound IgG was detected following a 1-h incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence—Paraffin sections of mouse testis (Zyagen) were deparaffinized using xylene, rehydrated using a graded series of 100, 95, and 80% ethanol, and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Tissue sections were heated in a microwave oven for 10 min in 10 mm citrate solution (pH 6) for antigen retrieval. Isolated testicular cells and sperm were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Mm.290718 domain-expressing HEK293T and GC-2 cells were washed twice with 1 mm calcium chloride and 1 mm magnesium chloride. After blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 min, samples were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody and/or Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) at 1:1000 dilution, and stained with Hoechst 33342 dye (Sigma). Fluorescence signals were observed under a microscope (DMLB; Leica Microsystems).

Immunoprecipitation—Testes and Mm.290718 domain-expressing HEK293T cells were lysed in nonionic detergent (1% Nonidet P-40) lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm sodium chloride, 50 mm Tris-Cl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm aprotinin, 1 mm leupeptin, 1 mm pepstatin). Total tissue lysates (500 μg) were incubated with 0.5 μg of anti-Mm.290718 antibody and protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) for 4 h at 4 °C. Total cell lysates (600 μg) were incubated with 0.5 μg of anti-GFP antibody and protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) for 8 h at 4 °C. Protein A beads were washed in a 1% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer at 4 °C three times and separated on an 8% SDS gel.

Enzymatic Digestion of Immunoprecipitated Protein Samples—Protein elution from antibody beads was performed using 8 m urea in 100 mm Tris (pH 8) buffer solution. Eluted proteins were reduced with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (final concentration of 5 mm) at room temperature for 30 min, and alkylated with iodoacetamide (final concentration of 25 mm) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The sample was diluted with 2 m urea using 100 mm Tris buffer solution (pH 8). CaCl2 was added to a final concentration of 5 mm, and the proteins were digested in digestion buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mm CaCl2) using sequencing grade-modified trypsin (Promega) for 14 h at 37 °C with an enzyme to substrate ratio of 1:25. Trypsin digestion of eluted proteins was quenched by adding 90% formic acid (final concentration of 5%).

Capillary Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatography-MS/MS and Data Analysis—Digested proteins were loaded onto fused silica capillary columns (100 μm inner diameter, 360 μm outer diameter) containing 7.5 cm of 5-μm particle Aqua C18 reversed-phase column material (Phenomenex). The column was placed inline with an Agilent HP1100 quaternary LC pump, and a splitter system was used to achieve a flow rate of 250 nl/min. Buffer A (5% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) and buffer B (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) were used to create a gradient over 80 min. The gradient profile started with 3 min of 100% buffer A, followed by 5 min from 0 to 15% buffer B, 57 min from 15 to 55% buffer B, and 15 min from 55 to 100% buffer B. Eluted peptides were directly electrosprayed into an LTQ Ion Trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, Palo Alto, CA) by applying 2.3 kV of DC voltage. A data-dependent scan consisting of 1 full MS (400-2000 m/z) and 10 data-dependent MS/MS scans was used to generate MS/MS spectra of eluted peptides. Normalized collision energy of 35% was used throughout the data acquisition period. MS/MS spectra were compared with the Mouse IPI protein data base (version 3.31) using TurboSequest and SEQUEST Cluster Systems (14 nodes). DTASelect was used to filter the search results, and the following Xcorr and ΔCn values were applied to different charge states of peptides with a fully tryptic digested end requirement of 1.8 for singly charged peptides, 2.2 for doubly charged peptides, and 3.2 for triply charged peptides, with a ΔCn value of 0.08 for all charge states. Manual assignments of fragment ions in all filtered MS/MS spectra were followed to confirm the protein data base search results.

Cloning and Cell Culture—Mm.290718 cDNA sequences were amplified from mouse testis cDNA using the primers forward, 5′-GGA AGC TTG ATG GAG CCA TAC AGT-3′, and reverse, 5′-ATG TCG ACT CCA CTG CAA AGG GC-3′, incorporating 5′ HindIII and 3′ SalI sites, and cloned into the pEGFP-N2 vector (Clontech). The zinc finger domain, first, second, and third regions, ELM2, and/or SANT domain were amplified from mouse testis cDNA using the following primers: first region: forward, 5′-GCG TCG ACC GAT GGA GCC ATA CAG T-3′, and reverse, 5′-TAG GAT CCC TGA TGG GAC AGA GT-3′; second region: forward, 5′-TCG AAT TCA TGT CAG GAT CCC AGC C-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAG TCG ACA AGG AGA GTG CAG GCA G-3′; third region: forward, 5′-TCG AAT TCA TGC CAG GAG GGT GCC A-3′, and reverse, 5′-ATG TCG ACT CCA CTG CAA GGG GCC C-3′; zinc finger domain: forward, 5′-GCG AAT TCA TGC TGT GTG GGA AA-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCG GAT CCT CAG GAT GCA TAC TC-3′; ELM2 domain: forward, 5′-CCA GAA TTC GAT GCC ACA TAT CAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-TTG GAT CCT CAG GTT GGT GCC C-3′; SANT domain: forward, 5′-GGA ATT CGA TGC GAT ACA CAG GT-3′, and reverse, 5′-CGG ATC CTC ATC TTT TTC CAG ATG-3′; ELM2-SANT domain: forward, 5′-CCA GAA TTC GAT GCC ACA TAT CAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CGG ATC CTC ATC TTT TTC CAG ATG-3′; and subcloned into pEGFP-N2. HEK293T and GC-2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured at 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C. Cells were transiently transfected with the pEGFP vector construct using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 24 h after transfection, cells were fixed with formaldehyde, stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma), and analyzed for fluorescent signals using a microscope.

Primary Cell Culture—Testes were collected from 8-week-old ICR mice. Testes were encapsulated into Hepes buffer and then slightly disintegrated mechanically. The disintegrated seminiferous tubules were incubated in 0.5 mg/ml collagenase (type IV, Sigma) at 37 °C for 10 min with agitation. The buffer was passed through a 70-μm filter (BD Biosciences), and the seminiferous tubules were incubated in 0.5 mg/ml collagenase and 0.25 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma) at 37 °C for 10 min with agitation, and the buffer was then passed through 40-μm filter (BD Biosciences). The filtrate was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant was removed, and testicular cells in the pellet were washed with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. The isolated testicular cells were cultured using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 20 mm valproic acid (VPA, Sigma) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 20 h (8). After 20 h, we observed that somatic cells (<5%) isolated from mouse testis stuck to the dish, and the isolated testicular cells (>95%) were still in suspension. The different types of testicular cells were distinguishable by cell size and distinctive features of nucleus by Hoechst staining. We obtained pure testicular cells from the medium. The cell viability was ascertained by the 0.4% trypan blue.

RESULTS

Amino Acid Sequences and Specific Domains of Mm. 290718/ZFP541—The novel spermatogenic cell-specific gene Mm.290718 encodes 1302 residues (Fig. 1A) with a predicted molecular mass of 148 kDa. Based on our in silico analysis utilizing the InterProScan database and gene information at NCBI, the amino acid sequence of Mm.290718 is predicted to contain specific motifs and domains. First, Mm.290718 contains five zinc finger motifs (Fig. 1, A and B) that bind to DNA. Among the five motifs, three are found in the N terminus (positions 142-162, 170-190, and 198-221) and the other two are located at positions 40-860 and 1242-1262. These five domains represent the C2H2 type of zinc finger subfamily. The Mm.290718 gene was designated “zinc finger protein 541” (ZFP541) at NCBI during the course of our study. Accordingly, we denote the gene “Mm.290718/ZFP541” in this study. Second, the Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein contains an ELM2 (Egl-27 and MTA1 homology 2) domain (Fig. 1, A-C). The ELM2 domain is conserved with the consensus sequence AXX- LXXXXXDXXXAXXL. Both the Egl-27 protein in Caenorhabditis elegans and the MTA1 protein in human are components of a nucleosome-remodeling complex containing histone deacetylase (9). Finally, the Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein contains a SANT (Swi3, Ada2, co-repressor NCoR, and TFIIIB) domain (Fig. 1, A-C), a 50-residue motif consisting of three α-helices (10). The SANT domain is found in the subunits of a number of chromatin-remodeling complexes. Moreover, most ELM2 domain-containing proteins include the SANT domain (11). Together, the in silico features of Mm.290718/ZFP541 support the theory of a DNA-binding protein involved in chromatin remodeling.

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequence and specific domains of Mm.290718/ZFP541. A, amino acid sequence was deduced from the Mm.290718/ZFP541 gene sequence. The zinc finger motifs are underlined in black, and the conserved amino acids for the C2H2 type are shaded. The ELM2 domain is underlined in red, and the SANT domain is underlined in blue. The number of the amino acid sequence is presented on the right. B, domain structure of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is shown below the amino acid sequence. C, sequence alignments of ELM2 and SANT domains. Sequences were aligned using Clustal X (1.81). ELM2 domain sequences were compared among Hs MIER1, Mm MTA2, Hs MTA1, and Ce Egl-27. The consensus sequences are displayed below the sequences. SANT domain sequences of Hs SMARCC1, Sc Swi3, Hs NCoR2, and Sc Ada2 were compared. The hydrophobic residues of the SANT domain are marked with asterisks. The species names are as follows: Mm, Mus musculus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. GenBank™ accession numbers are as follows: Hs SMARCC1 (NM003074); Sc Swi3 (NP012359); Hs NCoR2 (NM006312); Sc Ada2 (NP010736); Hs MIER1 (AF515447); Mm MTA2 (AK159979); Hs MTA1 (NM004689); Ce Egl-27 (NM171011).

Characterization of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in Mouse Spermatogenic Cells—To determine the expression profile of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in spermatogenic cells, we generated a polyclonal antibody against a glutathione S-transferase recombinant protein containing the N-terminal zinc finger motif. Immunoblot analysis was performed on testes from normal and germ cell-devoid mutant mice. Mm.290718/ZFP541 with a molecular size of 159 kDa was detected in normal but not germ cell-lacking testis, suggestive of germ cell-specific protein expression (Fig. 2A). Further immunoblot analysis was performed with mouse testis obtained at different times after birth. Mm.290718/ZFP541 was expressed in 16-day-old postnatal mouse testis, and its level increased during development (Fig. 2B). Most cells in the testis on day 8 are somatic, and the proportion of germ cells increases as spermatogenesis proceeds. Thus, the data suggest germ cell-specific expression of the Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein. To determine the expression pattern of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in germ cells during spermatogenesis, the protein level was examined in cells from different stages during sperm development. Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein was detected in testicular cells, but not testicular and mature sperm (Fig. 2C), indicating developmentally regulated expression. To further establish the cellular localization of Mm.290718/ZFP541, immunohistochemical analysis was performed using paraffin sections of adult mouse testis. In seminiferous tubules of paraffinized sections, we observed the Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein signal in spermatocytes and round spermatids. The protein was specifically localized in the cell nuclei (Fig. 2D). However, Mm.290718/ZFP541 was absent from cells beyond the stage of round spermatids. Our results collectively demonstrate that Mm.290718/ZFP541 is a nuclear protein, and its expression in spermatogenic cells is regulated in a developmental stage-dependent manner.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in mouse spermatogenic cells. A, total lysates from wild-type (WT) and germ cell-devoid testes of W/Wv mutant mice were blotted with the anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 antibody. Mm.290718 was observed only in the wild-type mouse testes. The anti-α-tubulin antibody was used as a control. B, stage-specific expression of Mm.290718/ZFP541 during spermatogenesis was examined by immunoblotting using total lysates obtained from prepubertal and adult male mice (aged 8, 16, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56 days). The anti-α-tubulin antibody was used as a control. C, protein samples from testicular cells (TC), testicular sperm (TS), and mature sperm (S) were blotted with the anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 and anti-ADAM2 antibodies. Mm.290718/ZFP541 was present only at the testicular cell stage. The anti-ADAM2 antibody was used as a control. D, immunohistochemical analysis of Mm.290718/ZFP541. Paraffin sections of mouse testis were stained with normal anti-rabbit serum and the anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 antibody. Hoechst 33342 dye was used to stain the nucleus. Mm.290718/ZFP541 was only detected in the nuclei of spermatocytes and round spermatids. Ab, specific antibody; Hoechst, Hoechst staining; Merge, merged images between antibody and Hoechst. Scale bar = 10 μm.

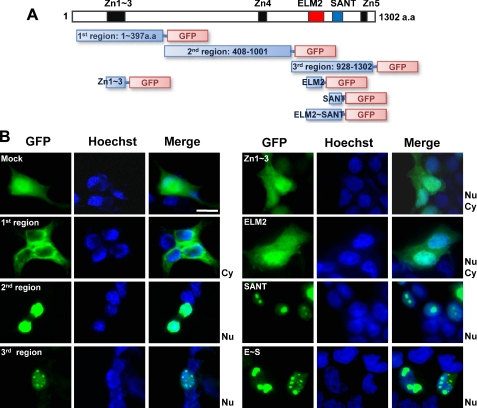

Subcellular Localization of Mm.290718/ZFP541—To further investigate the subcellular localization of Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein at the domain level, GFP-tagged cDNA sequences corresponding to the various domains and regions of Mm.290718/ZFP541 were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3, A and B). The first region containing three zinc finger motifs was localized mainly in the cytoplasm. Cells transfected with only the zinc finger motifs displayed a localization pattern similar to the control (nucleus and cytoplasm). In contrast, the second region containing one zinc finger motif was identified specifically in the nucleus. Upon transfection of cells with the ELM2 domain, we detected the signal in the nucleus and cytoplasm, similar to control cells. In contrast, the SANT and ELM2-SANT domains were only found in the nucleus. The nuclear localization pattern was similar with the third region containing ELM2 and SANT domains and the final zinc finger motif. In these cases, GFP signals were most abundant in the subnuclear spherical regions (Fig. 3B). Our data suggest that specific zinc finger motifs and the SANT domain are responsible for targeting of the Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein to the nucleus. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the GFP-tagged proteins could behave differently from the way the native proteins would, and the localization patterns in HEK293T cells could be different from those in germ cells.

FIGURE 3.

Subcellular localization of Mm.290718/ZFP541. A, schematic diagrams of pEGFP-N2-Mm.290718/ZFP541 cDNA regions subjected to transfection. B, HEK293T cells were transfected with cDNA sequences of Mm.290718/ZFP541 mutant constructs and observed after 24 h. 100-200 cells were observed in each transfection experiment. 30% of the cells in average were positive for the GFP signal. The pEGFP-N2 vector was used as a positive control (Mock). The Hoechst 33342 dye was used for nuclear staining. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Identification of Proteins Associated with Mm.290718/ZFP541 by Proteomic Analysis—To establish the functional characteristics of Mm.290718/ZFP541, we identified the interacting proteins. Immunoprecipitation with protein lysates from mouse testis was performed using the anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 antibody. Precipitates were subjected to tryptic digestion, followed by mass spectrometry analysis, such as capillary reverse phase liquid chromatography-MS/MS and peptide mass fingerprinting. These experiments resulted in the identification of 11 proteins, with reproducibility in three individual experiments (Table 2). The identified proteins include a previously unexplored potential testis-specific protein (KCTD19), a critical protein for transcription regulation and chromatin organization (HDAC1), a well known spermatogenic cell-specific molecular chaperone (HSPA2, also known as HSP70.2), and several proteins related to the survival of motor neuron (SMN) complex (deoxynucleotidyltransferase terminal-interacting protein 1, gem-associated protein 5, small nuclear ribo-nucleoprotein Sm D1, probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX20, and survivor of motor neuron protein-interacting protein 1 with unknown function). Based on the properties of Mm.290718/ZFP541 predicted from in silico analyses (zinc finger motifs and the SANT domain), cell type distribution (spermatogenic cells), and subcellular localization (nucleus) results, we further characterized the interacting KCTD19, HSPA2, and HDAC1 proteins (see below).

TABLE 2.

Proteins associated with Mm.290718/ZFP541

| No. | Protein description | Swiss-Prot (UniProtKB) | Matched peptidea | Xcorr/ΔCn (max)b | Measured mass (kDa)/pIc | Protein coverage (%)d | Peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Potassium channel tetramerization domain containing protein Kctd19 | KCTD19_MOUSE (Q562E2-2) | 14 | 6.83/0.53 | 107.3/6.5 | 23.1 | K. LAQFPDSLLWK. E |

| R. VRPADIPVAER. A | |||||||

| R. ASLNYWR. T | |||||||

| K. APLGLMDTPLLDTEEEVHYCFLPLDL VAK. Y | |||||||

| K. ILLPDNFSNIDVLEAEVEILEIPELTE AVR. L | |||||||

| K. YPDSALGQLR. I | |||||||

| R. LPLTETISEVYELCAFLDK. R | |||||||

| R. LPLTETISEVYELCAFLDKR. D | |||||||

| K. ETTACMPVDFQECSDR. T | |||||||

| R. SSQMEEAEQYTR. T | |||||||

| K. CTTINLTQKPDAK. D | |||||||

| R. SSSVEEASLHVPSGSEAAPQPGTSAAWK. A | |||||||

| K. DRESPAPEQPLPNANGTDNPGAILK. V | |||||||

| R. CVDLLIQR. G | |||||||

| 2 | Heat-shock-related 70-kDa protein 2 | HSP72_MOUSE (P17156) | 7 | 4.57/0.48 | 69.7/5.8 | 20.4 | R. GPAIGIDLGTTYSCVGVFQHGK. V |

| K. VQSAVITVPAYFNDSQR. Q | |||||||

| K. DAGTITGLNVLR. I | |||||||

| K. GQIQEIVLVGGSTR. I | |||||||

| K. SINPDEAVAYGAAVQAAILIGDK. S | |||||||

| K. SENVQDLLLLDVTPLSLGIETAGGVMT PLIK. R | |||||||

| K. CQEVINWLDR. N | |||||||

| 3 | Histone deacetylase 1 | HDAC1_MOUSE (O09106) | 3 | 4.60/0.22 | 55.0/5.5 | 8.3 | K. YGEYFPGTGDLR. D |

| K. YYAVNYPLR. D | |||||||

| K. LHISPSNMTNQNTNEYLEK. I | |||||||

| 4 | Deoxynucleotidyltransferase terminal-interacting protein 1 | TDIF1_MOUSE (Q99LB0) | 4 | 4.76/0.38 | 36.8/9.1 | 17.1 | R. AVLQPSINEEIQGVFNK. Y |

| R. DNVGEEVDAEQLIQEACR. S | |||||||

| R. LNESTTFVLGSR. A | |||||||

| R. DLAASDDYR. G | |||||||

| 5 | Gem-associated protein 5 | GEMI5_MOUSE (Q8BX17) | 5 | 3.86/0.39 | 166.5/6.7 | 4.3 | R. VGPGAGASPGAPPFR. V |

| K. LSGEAFDINK. L | |||||||

| K. LPVHTEISWK. G | |||||||

| R. DCLVLATATHAK. A | |||||||

| R. SAFSVDTPEQCQAALQK. L | |||||||

| 6 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Sm D1 | SMD1_MOUSE (P62315) | 3 | 5.32/0.43 | 132.8/11.6 | 37.0 | K. LSHETVTIELK. N |

| K. NREPVQLETLSIR. G | |||||||

| R. YFILPDSLPLDTLLVDVEPK. V | |||||||

| 7 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX20 | DDX20_MOUSE (Q9JJY4) | 4 | 4.88/0.44 | 91.7/6.8 | 7.9 | R. AAAPVQAVEPTPASPWTQR. T |

| K. TQHLQELFSK. V | |||||||

| K. AAPPQESGCPAQLEEQVK. N | |||||||

| R. ETTASFSDTYQDYEEYWR. A | |||||||

| 8 | Heat-shock cognate 71 kDa protein | HSP7C_MOUSE (P63017) | 3 | 3.63/0.40 | 70.8/5.5 | 7.9 | K. STAGDTHLGGEDFDNR. M |

| R. ARFEELNADLFR. G | |||||||

| K. SINPDEAVAYGAAVQAAILSGDK. S | |||||||

| 9 | Splice isoform 1 of Y-box binding protein-2 | YBOX2_MOUSE (Q9Z2C8-1) | 5 | 4.66/0.35 | 38.2/10.9 | 22.8 | R. TPGNQATAASGTPAPPAR. S |

| R. SQADKPVLAIQVLGTVK. W | |||||||

| R. GPRPPNQQQPIEGSDGVEPK. E | |||||||

| K. ETAPLEGDQQQGDER. V | |||||||

| Y. FQRRRQQPPGPR. Q | |||||||

| 10 | Tubulin α-1 chain | TBA1A_MOUSE (P68369) | 3 | 4.83/0.36 | 50.1/5.1 | 12.4 | K. TIGGGDDSFNTFFSETGAGK. H |

| R. AVFVDLEPTVIDEVR. T | |||||||

| R. FDGALNVDLTEFQTNLVPYPR. I | |||||||

| 11 | Survivor of motor neuron protein interacting protein 1 | GEMI2_MOUSE (Q9CQQ4) | 2 | 5.58/0.56 | 30.6/5.5 | 17.7 | K. QSVNISLSGCQPAPEGYSPTLQWQQQ QVAHFSTVR. Q |

| R. VPALNLLICLVSR. Y |

Number of non-redundant peptides that were identified for each protein.

Maximum Xcorr and ΔCn values using TurboSEQUEST software were obtained for any of the peptides identified for a single protein.

Data were calculated using TurboSEQUEST software.

Protein coverage was calculated based on the amino acid count.

Characterization of KCTD19 in Mouse Testis—KCTD19 interacting with Mm.290718/ZFP541 in spermatogenic cells are encoded by a novel gene (UniGene ID Mm.67628 and GenBank™ accession number NM_177791.2). In silico analyses show that the translated protein contains a potassium channel tetramerization domain-like BTB (for Broad-Complex, Tramtrack, and Bric-a-brac) or POZ (for Pox virus and zinc finger) domain. KCTD19 was examined at the gene and protein levels. RT-PCR analysis was performed using mouse cDNA obtained from different tissues and mouse testes on different postnatal days. The Kctd19 gene was transcribed exclusively in the testis (Fig. 4A), starting from day 12 (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we generated a polyclonal antibody against KCTD19 using a GST-KCTD19 (positions 648-747) recombinant protein. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the 107-kDa KCTD19 protein is expressed in normal testis but not germ cell-devoid testis (Fig. 4C). Testicular expression of the protein was initiated on day 16 (Fig. 4D). Moreover, KCTD19 was present in testicular germ cells but not testicular sperm and mature sperm (Fig. 4E). The highly similar expression patterns of KCTD19 and Mm.290718/ZFP541 (Fig. 2) indicate that the two proteins are regulated spatiotemporally by similar mechanisms or even the same pathway.

FIGURE 4.

Identification and characterization of KCTD19. To investigate the tissue distribution and developmental expression pattern of Kctd9, RT-PCR analyses were performed. A, Kctd19 gene was transcribed in normal testis but not germ cell-lacking testis (W/Wv). T, testis; B, brain; Li, liver; S, spleen; K, kidney; SK, skeletal muscle; Ov, ovary; G3PDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. B, stage-specific expression of Kctd19 was determined from mouse testes on different days after birth (8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, 30, and 84 days). C, total lysates from wild-type (WT) mouse testes and germ cell-lacking testes of W/Wv mutant mice were immunoblotted with the anti-KCTD19 antibody. KCTD19 was only found in normal mouse testis. The anti-α-tubulin antibody was used as a control. D, protein samples from testicular cells (TC), testicular sperm (TS), and mature sperm (S) were blotted with anti-KCTD19 and anti-ADAM2 antibodies. The testicular cell-specific expression pattern of KCTD19 was similar to that of Mm.290718/ZFP541. An anti-ADAM2 antibody was used as a control. E, stage-specific expression of KCTD19 during spermatogenesis was examined by immunoblotting using total lysates obtained from prepubertal and adult male mice (aged 8, 16, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, and 56 days). KCTD19 was present from day 16. The anti-α-tubulin antibody was used as a control.

Mm.290718/ZFP541 with KCTD19, HSPA2, and HDAC1, we performed immunoprecipitation analyses with total lysates from mouse testes using anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 and anti-KCTD19 antibodies (Fig. 5). Immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541, anti-KCTD19, anti-HSPA2, and anti-HDAC1 antibodies. The anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 and anti-KCTD19 antibodies effectively immunoprecipitated cognate proteins (Fig. 5). The immunoprecipitated samples contained all four proteins, verifying the proteomic analysis data (Fig. 5). We did not observe the protein band in other tissues, including kidney and spleen (data not shown). Comparison of the levels of precipitated and remaining protein in the supernatant with the total protein level revealed that nearly all Mm.290718/ZFP541 and KCTD19 form the complex. In contrast, partial amounts of HSPA2 and HDAC1 composed the complex. This result appears compatible with the role of HSPA2 as a chaperone for diverse proteins in spermatogenic cells (12-15). The HDAC1 protein is also expressed in somatic cells, and accordingly, we assume that Mm.290718/ZFP541-free HDAC1 is present in testicular somatic cells. Our results confirm the existence of a male germ cell-specific complex comprising Mm.290718/ZFP541, KCTD19, HSPA2, and HDAC1 proteins.

FIGURE 5.

Presence of the Mm.290718/ZFP541-HDAC1-HSPA2 complex in mouse testes. Testes were lysed with 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer, and the tissue lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 and anti-KCTD19 antibodies. Normal rabbit serum (NRS) was used as a control. The precipitated sample was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541, anti-KCTD19, anti-HSPA2, and anti-HDAC1 antibodies. The same blots were used for immunoblotting (IB) with each antibody. Anti-α-tubulin antibody was used as the loading control. Samples for the TL and S lanes (20 μg) and IP lane (1 mg) were loaded. TL, tissue lysate; S, supernatant; IP, immunoprecipitated protein.

Relationship between Mm.290718/ZFP541 and Histone Acetylation during Spermatogenesis—Histones are hyperacetylated and subsequently replaced by transition proteins during the post-meiotic stage of spermatogenesis (1, 16). Histone acetylation may be a prerequisite for chromatin condensation. Based on our finding that Mm.290718/ZFP541 is associated with HDAC1, we explored the relationship between Mm.290718/ZFP541 and histone acetylation. Spermatogenic cells were isolated from the seminiferous tubule of mouse testis, and co-immunostaining analysis was performed using anti-acetyl-lysine and anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 antibodies. We observed signals for Mm.290718/ZFP541 in the nuclei of spermatocytes and round spermatids but, remarkably, not in elongating or condensing spermatids (Fig. 6), thus confirming and extending our previous observation (Fig. 2D). Nuclear signals were stronger in spherical regions than other nucleoplasmic regions. In terms of histone acetylation, spermatocytes and round spermatids exhibited significant underacetylation (1). However, distinct hyperacetylation was observed in cells lacking Mm.290718/ZFP541 (elongating and condensing spermatids) (Fig. 6). Our findings clearly indicate that loss of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is correlated with histone acetylation.

FIGURE 6.

Stage specificity of Mm.290718/ZFP541 during spermatogenesis. Isolated spermatogenic cells were stained with anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 and anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies. The Mm.290718/ZFP541 protein was observed only in spermatocytes and round spermatids displaying predominant histone deacetylation, but not in elongating and condensing spermatids, which show a strong signal with the anti-acetyl-lysine antibody. 30-50 cells in each stage were observed in three individual observations. The percentages of cells with the Mm.290718/ZFP541 signal were over 80% in spermatocytes and round spermatids, and 0% in elongating and condensing spermatids. The percentages of cells with the acetylation signal were below 10% in spermatocytes and round spermatids, and over 90% in elongating and condensing spermatids. SC, spermatocyte; RS, round spermatid; ES, elongating spermatid; CS, condensing spermatid. Scale bar = 5 μm.

Interaction of the SANT Domain of Mm.290718/ZFP541 with HDAC1—Proteins containing SANT and ELM2 domains are implicated in chromatin remodeling involving HDAC (11, 17), so we determined whether these domains of Mm.290718/ZFP541 function as HDAC-binding modules. We expressed GFP-tagged ELM2 and/or SANT domains of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in HEK293T and GC-2 cells, and we observed HDAC1 by immunostaining (Fig. 7A). Although we utilized the GC-2 cells, derived by immortalization of germ cells (spermatocytes), in this assay it should be noted that many germ cell-specific genes are not expressed in these cells. Nonetheless, the GC-2 cells could be induced to partially undergo meiosis and show signs of morphological differentiation similar to spermiogenesis (18). In HEK293T cells, HDAC1 is distributed to the nucleus in control (mock) cells, with a similar localization pattern as that in the ELM2 domain-expressing cells. GFP signals were detected in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. In contrast, in SANT and ELM2-SANT domain-expressing cells, GFP signals were detected only in the nucleus and were particularly strong in subnuclear speckled regions. This finding is consistent with the data presented in Figs. 3B and 6. The localization pattern of HDAC1 in these cells was similar to that of GFP signals (Fig. 7A). We additionally performed immunoprecipitation analyses. Immunoprecipitated samples from SANT and ELM2-SANT domain-expressing cells contained HDAC1. Interestingly, a higher level of HDAC1 was observed in the immunoprecipitated complex from ELM2-SANT domain-expressing cells than from SANT domain-expressing cells (Fig. 7B). In GC-2 cells, the patterns of the GFP signals were similar to those in HEK293T cells. HDAC1 was found to be distributed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm in the control and ELM2 domain-expressing cells. However, the HDAC1, in the SANT and ELM2-SANT domain-expressing GC-2 cells, was distributed only in the nucleus. Notably, HDAC1 was localized to the entire region of the nucleus (Fig. 7C). Our results collectively indicate that the SANT domain of Mm.290718/ZFP541 interacts directly with HDAC1, restricting its localization to the nucleoplasm. The ELM2 domain appears to promote interactions of the SANT domain.

FIGURE 7.

Regulation of HDAC1 by Mm.290718/ZFP541. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with enhanced GFP-cDNA corresponding to different regions (ELM2, SANT, and ELM2-SANT, as shown in Fig. 3) of Mm.290718/ZFP541, and immunostained with the anti-HDAC1 antibody. HDAC1 in mock and ELM2-expressing cells was identified in the nucleoplasm. In contrast, HDAC1 in SANT- and ELM2-SANT-expressing cells was present in the nucleoplasm, with strong signals in subnuclear spherical regions. Arrows indicate the regions with strong signals in SANT- and ELM2-SANT-expressing cells. The merged image shows co-localization between Mm.290718 in SANT- and ELM2-SANT-expressing cells (green), HDAC1 (red), and nucleus (blue). 100-200 cells were observed in each transfection experiment. 20-40% of the cells were positive for the GFP signals. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, HEK293T cells overexpressing various regions of Mm.290718/ZFP541 mutants (pEGFP-N2-ELM2, SANT, and ELM2-SANT domains) were immunoprecipitated (IP) using the anti-GFP-antibody. Subsequently, complexes were immunoblotted (IB) using anti-HDAC1 and anti-GFP antibodies. M, Mock; E, ELM2 domain; S, SANT domain; E∼S, ELM2-SANT domain. C, same transfection and immunostaining experiments, as performed in A were subjected to GC-2 cells. HDAC1 in mock and ELM2-expressing cells was present in the nucleus and cytoplasm. In contrast, HDAC1 in SANT- and ELM2-SANT-expressing cells was present only in the nucleus. The merged image shows co-localization between Mm.290718 in SANT- and ELM2-SANT-expressing cells (green), HDAC1 (red), and nucleus (blue). 100-200 cells were observed in each transfection experiment. 10% of the cells in average were positive for the GFP signal. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Inhibition of the Activity of the HDAC1 Complex in Spermatogenic Cells—To further investigate the relationship between Mm.290718/ZFP541 and HDAC1 during spermatogenesis, we isolated the spermatogenic cells from mouse testes and treated them with one of the widely used HDAC inhibitors, VPA. It is specific for class I HDACs and interrupts corepressor-associated HDACs (19). As shown in Fig. 8, A and B, we observed premature hyperacetylation in round spermatids treated with VPA. Whereas ∼60% of round spermatids were underacetylated in control cells, about 70% of cells treated with VPA were hyperacetylated. VPA treatment resulted in a significant reduction in the population of cells with a high level of Mm.290718/ZFP541 (Fig. 8, A and B). Indeed, immunoblot analysis revealed that the level of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is dramatically reduced (40% of control) in the VPA-treated spermatogenic cells (Fig. 8C). KCTD19 was also reduced (56% of control) in amount. By contrast, the level of HDAC1 was found to be slightly decreased (84% of control), and HSPA2 was normally expressed in the presence of VPA. These results suggest that the integrity of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is important for maintaining histone deacetylation in spermatogenic cells.

FIGURE 8.

Inhibition of HDAC1 activity in spermatogenic cells. A, spermatogenic cells were incubated in the presence of an HDAC inhibitor, VPA (20 mm), for 20 h, and round spermatids were co-immunostained with the anti-Mm.290718/ZFP541 and anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies. The signal of Mm.290718/ZFP541 was observed in most of control cells with predominant histone deacetylation, In contrast, the majority of VPA-treated round spermatids showed weak signals of Mm.290718/ZFP541, but with strong acetylation signals. 110-170 cells were observed in each group. Nucleus was stained by Hoechst. Scale bar = 5 μm. B, graph represents the percentages of control cells (white bars) and VPA-treated cells (black bars) with high (higher than median intensity, >2.0E+06) or low level (lower than median intensity, <2.0E+06) of immune signals. The integrated intensity of Mm.290718/ZFP541 and acetyl-lysine was measured using an imaging software, Meta-Morph (Universal Imaging Corp.; Downingtown, PA). More than 100 cells were counted in each condition. Values are mean ± S.D. from triplicate in three independent observations. *, p < 0.05. C, total lysates (15 μg) from control cells (C) and VPA-treated cells (VPA) were subjected to Western blot analysis with the anti-290718/ZFP541, anti-KCTD19, anti-HDAC1, and anti-HSPA2 antibodies.

Expression of ELM2 and SANT Domain-containing Genes in Testis—To explore the uniqueness of Mm.290718/ZFP541, we investigated the expression profiles of all the known genes encoding ELM2 and SANT domain-containing proteins. To date, 11 such genes have been identified, specifically metastasis-associated 1, 2, and 3 (Mta1, Mta2, and Mta3), mesoderm induction early response family member 1, 2, and 3 (Mier1, Mier2, and Mier3), REST co-repressor 1, 2, and 3 (Rcor1, Rcor2, and Rcor3), arginine-glutamic acid dipeptide repeats (Rere), and transcriptional regulating factor 1 (Trerf1) (9, 11, 20-23). RT-PCR analysis was performed using cDNA from testicular germ cells and germ cell-devoid testes (Fig. 9). Six of the genes (Mta2, Mier1, Rcor2, Rcor3, Rere, and Trerf1) were expressed in testicular somatic cells but not germ cells. The other five genes (Mta1, Mta3, Mier2, Mier3, and Rcor1) were expressed in both somatic and germ cells. These data suggest that Mm.290718/ZFP541 is the only spermatogenic cell-specific gene encoding the ELM2 and SANT domain-containing protein, validating the importance of this protein and its complex in the chromatin-remodeling process unique to spermatogenic cells.

FIGURE 9.

Expression patterns of ELM2 and SANT domain-containing genes in testis. Complementary DNA samples were obtained from testicular germ cells (TGC) isolated from normal adult mouse testes and testes of germ cell-devoid mutant mice (W/Wv). Germ cell-devoid testes were used to evaluate gene expression in testicular somatic cells. Mta1, Mta3, Mier2, Mier3, and Rcor1 genes were expressed in TGC and somatic cells. Mta2, Mier1, Rcor2, and Rere genes were expressed in somatic cells but not in TGC. Rcor3 and Trerf1 genes were not expressed in the testis. The Mm.290718/ZFP541 gene was expressed only in TGC. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) gene was included as a positive control. Mta1, Metastasis-associated 1; Mier1, mesoderm induction early response 1; Rcor1, REST co-repressor 1; Rere, arginine-glutamic acid dipeptide (RE) repeats; Trerf1, transcriptional regulating factor 1.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified and characterized a novel protein, Mm.290718/ZFP541, expressed solely in germ cells. The protein contains zinc finger motifs, as well as ELM2 and SANT domains. The zinc finger motif is a DNA-binding domain present in several transcription factors. The ELM2 domain possibly functions in DNA binding, protein-protein interactions, and nucleosome remodeling (9, 11), whereas the SANT domain has been identified in nuclear receptor co-repressors, transcriptional regulatory factors, and subunits of chromatin-remodeling complexes (10, 24). Here we show for the first time that Mm.290718/ZFP541, a 159-kDa protein, is present in the nuclei of spermatogenic cells at specific stages (spermatocytes and round spermatids). Moreover, Mm.290718/ZFP541 is associated with a number of proteins, including HDAC1. The SANT domain of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is responsible for interactions with HDAC1.

Our study provides key information on the potential function of Mm.290718/ZFP541 in a critical process during spermatogenesis. Mm.290718/ZFP541 is implicated in chromatin reorganization during the post-meiotic phase of male germ cell development. During this process, histones are replaced by transition proteins, which are, in turn, substituted by protamines. Consequently, chromatin is remodeled and highly condensed, leading to transcriptional inactivation of the male genome and morphological changes in the nucleus (1). The first step in chromatin remodeling is histone deacetylation. Core histones are deacetylated in pachytene spermatocytes and early stage round spermatids. HDACs are fully activated to deacetylate the global histones. The acetylation status is markedly altered in the following stages of spermatogenesis. Histones are hyperacetylated in elongating spermatids. HDAC degradation induces hyperacetylation, which initiates histone replacement and chromatin condensation (25-27). Chromodomain-Y-like (CYDL) protein possibly participates in histone acetylation in elongating spermatids (28). However, limited information is currently available on the mechanisms underlying HDAC degradation and abrupt hyperacetylation during the transition period from round to elongating spermatid formation (29). We propose that Mm.290718/ZFP541 is at least partly responsible for transcriptional repression and the initiation of subsequent histone hyperacetylation (Fig. 10). This theory is supported by a number of findings. First, Mm.290718/ZFP541 distribution is restricted to spermatocytes and round spermatids. Second, Mm.290718/ZFP541 is associated with HDACs, which are unable to operate alone and require co-factors for deacetylase activity (30-32). The SANT domain of Mm.290718/ZFP541 translocates and interacts with HDAC1. Third, the absence of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is precisely correlated with hyperacetylation in spermatids. Fourth, the integrity of Mm.290718/ZFP541 is evidently related to the regulation of the HDAC activity, as shown in VPA-treated spermatogenic cells. Finally, among the ELM2 and SANT domain-containing proteins, Mm.290718/ZFP541 is the only protein unique to spermatogenic cells.

FIGURE 10.

Model for chromatin remodeling during spermatogenesis. A stable complex containing Mm.290718/ZFP541, HDAC1, HSPA2, and KCTD19 is present in round spermatids (RS) where histones are underacetylated. During transition from round spermatids to elongating spermatids (ES), Mm.290718/ZFP541 and KCTD19 expression are lost. Consequently, HDAC1 becomes degraded or inactive, and histones are hyperacetylated. This could produce a signal for transition proteins (chaperoned by HSPA2) to replace hyperacetylated histones (part not shown).

In addition to HDAC1, several proteins are associated with Mm.290718/ZFP541, including HSPA2, KCTD19, and SMN. None of the known complexes containing HDAC1 have components that are similar to those of Mm.290718/ZFP541. For instance, a major HDAC-containing complex, NuRD, includes at least seven components, including HDAC1/2, MTA1/2, MBD3, Mi-2RbAp48, TbAp46, and p66 (17, 33). Two of the components, HSPA2 and KCTD19, in the Mm.290718/ZFP541 complex are specific for male germ cells. HSPA2 is an essential molecular chaperone for meiosis. Male mice lacking this protein are infertile because spermatogenesis is arrested in latepachytene spermatocytes, and these cells undergo apoptosis (12, 13, 15). Recently, HSPA2 was identified as the chaperone of transition proteins, indicating that the protein also functions during the post-meiotic phase of spermatogenesis (14). Our finding on the association of HSPA2 with the Mm.290718/ZFP541 complex suggests a new role of HSPA2 as a chaperone for components of the complex. KCTD19 is a novel protein with similar expression characteristics as Mm.290718/ZFP541 and contains the BTB/POZ domain. In other proteins, this domain interacts with components of the HDAC co-repressor complexes (34). Thus, it is reasonable to propose that KCTD19 utilizes the BTB/POZ domain to form the Mm.290718/ZFP541 complex. The components that are directly associated with HSPA2 and KCTD19 remain to be identified. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that these spermatogenic cell-specific proteins are important for generating and maintaining the structure of the Mm.290178/ZFP541 complex unique to spermatogenic cells (Fig. 10). The other proteins associated with the Mm.290178/ZFP541 complex include components that form the SMN complex. These proteins were identified by proteomic analysis but have not been subjected to immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting experiments. In general, the SMN complex is concentrated in distinct subnuclear structures called “gems” and may function in ribonucleoprotein assembly processes (35, 36). Notably, Mm.290718/ZFP541 is localized densely in the subnuclear spherical regions. Further studies are necessary to establish how SMN complex proteins are associated with the Mm.290718/ZFP541 complex, and whether they are directly related to subnuclear localization.

In conclusion, our comprehensive findings provide original information on a novel germ cell-specific protein. Mm.290718/ZFP541 is a nuclear protein regulated stage-specifically during spermatogenesis, and it forms an authentic complex together with HDAC1, HSPA2, and KCTD19 in spermatogenic cells. In particular, the localization and interaction of HDAC1, a critical protein for nuclear reorganization during spermatogenesis, are regulated by the ELM2 and SANT domains of Mm.290718/ZFP541. Based on these findings, we propose a model for chromatin remodeling during spermatogenesis (Fig. 10). Specifically, Mm.290718/ZFP541 is associated with HDAC1, HSPA2, and KCTD19 in spermatocytes and round spermatids. Histones are deacetylated by the stable complex containing HDAC1 at these stages. During transition from the round to elongated spermatid stages, Mm.290718/ZFP541 and KCTD19 expression is lost. Disappearance of Mm.290718 and KCTD19 induces the dissociation or instability of HDAC1, leading to histone acetylation, subsequently resulting in replacement of histone by transition protein associated with HSPA2. Finally, we re-designate Mm.290718/ZFP541 as SHIP1 (spermatogenic cell HDAC-interacting protein 1).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant ZO1 ES070077 (Project 1, Intramural Research Program, NIEHS). This work was also supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation Grant RO1-2007-000-20116, Korean Systems Biology Research Grant M10503010001-06N0301-00110, and GIST Systems Biology Infrastructure Establishment grant. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: HDAC1, histone deacetylase 1; HSPA2, heat shock protein A2; KCTD19, potassium channel tetramerization domain 19; RT, reverse transcription; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; VPA, valproic acid; GFP, green fluorescent protein; SMN, survival of motor neuron.

References

- 1.Caron, C., Govin, J., Rousseaux, S., and Khochbin, S. (2005) Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 38 65-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho, C., Jung-Ha, H., Willis, W. D., Goulding, E. H., Stein, P., Xu, Z., Schultz, R. M., Hecht, N. B., and Eddy, E. M. (2003) Biol. Reprod. 69 211-217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho, C., Willis, W. D., Goulding, E. H., Jung-Ha, H., Choi, Y. C., Hecht, N. B., and Eddy, E. M. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28 82-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong, S., Choi, I., Woo, J. M., Oh, J., Kim, T., Choi, E., Kim, T. W., Jung, Y. K., Kim, D. H., Sun, C. H., Yi, G. S., Eddy, E. M., and Cho, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 7685-7693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi, E., Lee, J., Oh, J., Park, I., Han, C., Yi, C., Kim Do, H., Cho, B. N., Eddy, E. M., and Cho, C. (2007) BMC Genomics 8 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosario, M. O., Perkins, S. L., O'Brien, D. A., Allen, R. L., and Eddy, E. M. (1992) Dev. Biol. 150 1-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phelps, B. M., Koppel, D. E., Primakoff, P., and Myles, D. G. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111 1839-1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backliwal, G., Hildinger, M., Kuettel, I., Delegrange, F., Hacker, D. L., and Wurm, F. M. (2008) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 101 182-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solari, F., Bateman, A., and Ahringer, J. (1999) Development (Camb.) 126 2483-2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer, L. A., Latek, R. R., and Peterson, C. L. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5 158-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding, Z., Gillespie, L. L., and Paterno, G. D. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 250-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dix, D. J., Allen, J. W., Collins, B. W., Mori, C., Nakamura, N., Poorman-Allen, P., Goulding, E. H., and Eddy, E. M. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 3264-3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dix, D. J., Allen, J. W., Collins, B. W., Poorman-Allen, P., Mori, C., Blizard, D. R., Brown, P. R., Goulding, E. H., Strong, B. D., and Eddy, E. M. (1997) Development (Camb.) 124 4595-4603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Govin, J., Caron, C., Escoffier, E., Ferro, M., Kuhn, L., Rousseaux, S., Eddy, E. M., Garin, J., and Khochbin, S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 37888-37892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu, D., Dix, D. J., and Eddy, E. M. (1997) Development (Camb.) 124 3007-3014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rousseaux, S., Reynoird, N., Escoffier, E., Thevenon, J., Caron, C., and Khochbin, S. (2008) Reprod. Biomed. Online 16 492-503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahringer, J. (2000) Trends Genet. 16 351-356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann, M. C., Hess, R. A., Goldberg, E., and Millan, J. L. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 5533-5537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlicher, M., Minucci, S., Zhu, P., Kramer, O. H., Schimpf, A., Giavara, S., Sleeman, J. P., Lo Coco, F., Nervi, C., Pelicci, P. G., and Heinzel, T. (2001) EMBO J. 20 6969-6978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manavathi, B., Singh, K., and Kumar, R. (2007) Nucl. Recept. Signal. 5 e010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimes, J. A., Nielsen, S. J., Battaglioli, E., Miska, E. A., Speh, J. C., Berry, D. L., Atouf, F., Holdener, B. C., Mandel, G., and Kouzarides, T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 9461-9467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, L., Charroux, B., Kerridge, S., and Tsai, C. C. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9 555-562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, W., Liu, X. P., Xu, R. J., and Zhang, Y. Q. (2007) Asian J. Androl. 9 345-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aasland, R., Stewart, A. F., and Gibson, T. (1996) Trends Biochem. Sci. 21 87-88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Govin, J., Caron, C., Lestrat, C., Rousseaux, S., and Khochbin, S. (2004) Eur. J. Biochem. 271 3459-3469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazzouri, M., Pivot-Pajot, C., Faure, A. K., Usson, Y., Pelletier, R., Sele, B., Khochbin, S., and Rousseaux, S. (2000) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 79 950-960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sassone-Corsi, P. (2002) Science 296 2176-2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caron, C., Pivot-Pajot, C., van Grunsven, L. A., Col, E., Lestrat, C., Rousseaux, S., and Khochbin, S. (2003) EMBO Rep. 4 877-882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimmins, S., and Sassone-Corsi, P. (2005) Nature 434 583-589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Ruijter, A. J., van Gennip, A. H., Caron, H. N., Kemp, S., and van Kuilenburg, A. B. (2003) Biochem. J. 370 737-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naar, A. M., Lemon, B. D., and Tjian, R. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70 475-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolffe, A. P. (1996) Science 272 371-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayer, D. E. (1999) Trends Cell Biol. 9 193-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huynh, K. D., and Bardwell, V. J. (1998) Oncogene 17 2473-2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paushkin, S., Gubitz, A. K., Massenet, S., and Dreyfuss, G. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14 305-312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirri, V., Urcuqui-Inchima, S., Roussel, P., and Hernandez-Verdun, D. (2008) Histochem. Cell Biol. 129 13-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]