Abstract

With the impending surge in the number of older adults, primary care clinicians will increasingly need to manage the care of vulnerable elders. Caring for vulnerable elders is complex because of their wide range of health goals and the interdependence of medical care and community supports needed to achieve those goals. In this article, we identify ways a primary care practice can reorganize to improve the care of vulnerable elders. We begin by identifying important outcomes for vulnerable elders and three key processes of care (communication, developing a personal care plan for each patient, and care coordination) needed to achieve these outcomes. We then describe two delivery models of primary care for vulnerable elders – co-management, and augmented primary care. Finally, we discuss how the physical plant, people, workflow management, and community linkages in a primary care practice can be restructured to better serve these patients.

KEY WORDS: primary care, practice redesign, quality of care, quality improvement, older adults

INTRODUCTORY SCENARIO

As a primary care physician in a rural practice, you are seeing a new patient, Ms. M, an 85-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis and insulin-requiring type-2 diabetes who lives alone. She is brought in by four concerned daughters because they noticed that Ms. M seems to be having more problems with her memory. The patient denies any memory problems. Ms. M is also treated by a rheumatologist and recently was started on prednisone for a flare up of her symptoms. Physical examination is remarkable for a body mass index of 33, a score of 21 out of 30 points on the Mini Mental State Examination, and decreased range of motion in Ms. M’s fingers, hips, and knees. Laboratory testing is notable for a hemoglobin A1c of 9.1%.

Patients such as Ms. M pose a dilemma for primary care clinicians. If the patient is taking her insulin correctly, she may need an increase in her insulin dose to improve her glycemic control. Whether a recent increase in glucocorticoids for a rheumatoid flare might be contributing to poor glycemic control is also in question. Conversely, Ms. M may be forgetting or having trouble injecting her insulin, and increasing her insulin could lead to severe hypoglycemia now that medication-taking is (temporarily) being supervised by Ms. M’s daughters. The memory problems, which could be symptoms of early dementia or depression, also raise questions about the patient’s continued ability to live by herself without supervision.

BACKGROUND

Complicated scenarios like the one above, with interactions between medical and social components, are frustrating to many primary care clinicians,1,2 who typically work in systems that have no support for managing such problems and allot a short (usually 10 to 20 min) amount of time per patient encounter. Yet primary care clinicians are usually the first point of contact for patients seeking evaluation for their health concerns and guidance about where to turn for additional services, and in most cases primary care clinicians are the ones who provide continuity and coordination of care for this group of patients. In one study, about 20% of community-dwelling adults over age 65 were classified as vulnerable, with the average vulnerable elder being 81 years of age;3 thus, of the 37 million Americans over the age of 65, about 7.8 million might be classified as vulnerable. This article highlights practice improvement strategies for optimizing the quality of care of vulnerable elders.

IDENTIFYING VULNERABLE ELDERS WITHIN PRIMARY CARE

We define vulnerable elders as individuals aged 65 years and older whose age, self-reported health, and/or functional limitations put them at increased risk for either death or functional decline. Vulnerable elders can be easily identified by the Vulnerable Elders Survey, a 13-item screen that can be performed by non-clinicians in less than 5 min.4 Older persons classified as vulnerable by this survey are at a fourfold risk for death or functional decline in the next 2 years as compared to their peers.4

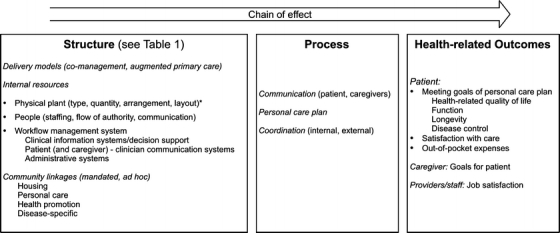

FRAMEWORK FOR IDENTIFYING PRACTICE IMPROVEMENT STRATEGIES (FIG. 1)

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework. Italicized words represent key domains of structure, processes, and outcomes of primary care for vulnerable elders. The arrow refers to the direction of causation, and the words “chain of effect”57 indicate a linked relationship between structure and process, and process and outcomes. *For example: exam room layout to accommodate wheelchairs/walkers, multiple individuals; equipment that facilitates transfer from chair to exam table.

We ground our practice improvement strategies in a framework based on several existing conceptual and practice models. Donabedian’s “structure-process-outcome” categorization serves as the foundation.5 The Chronic Care Model,6 with its emphasis on linkage between the medical care system and community resources, helps us identify the components of the framework for providing optimal care. Finally, we include elements of the medical home,7,8 defined as “a partnership approach with families to provide primary health care that is accessible, family centered, coordinated, comprehensive, continuous, compassionate, and culturally effective.”9 The resulting framework focuses on the organization of day-to-day work in a variety of primary care settings and specifies the outcomes of care that are important for vulnerable elders, as well as the key aspects of primary care structure and process that are relevant to achieve those outcomes.

PRACTICE IMPROVEMENT GOALS

Outcomes for Vulnerable Elders

Practice improvement strategies should aim to optimize outcomes for vulnerable elders. These include outcomes that are important to patients of all ages, including health-related quality of life, function, longevity, and disease control. For vulnerable elders, however, the relative importance of each of these outcomes may be expected to vary depending on an individual’s illness burden, culture, and personal values.10 Furthermore, in many situations, caregivers’ surrogate goals for patients are an important outcome for primary care clinicians to consider, and conflicts between a patient’s and a surrogate’s goals may arise, signaling the need for further discussion. Patients’ out-of-pocket expenses, while important to all patients, may be particularly important to vulnerable elders. Their expenses may extend beyond medical care to hiring caregivers or paying for other supportive services that are not routinely covered by health insurance. Yet costs are often overlooked when treating elders.11 Finally, providers and staff need to find pleasure in their work in order to sustain primary care systems12 and improve patient outcomes.13

Processes of Care for Vulnerable Elders

Vulnerable elders face a highly individualized set of tradeoffs with respect to the desired outcomes of health-related quality of life, function, longevity, and disease control. Thus, there are no absolutes with respect to whether screening, diagnosis, or treatment must occur. Hence, the first (and most fundamental) process of care is communication with the patient and caregiver to arrive at informed decisions.

The second key process of care for vulnerable elders is developing and maintaining a personal care plan (goals of care followed by decisions about screening and prevention, diagnosis, treatment, referral, and care coordination). The spectrum of personal care plans ranges from a pure self-management plan to a pure care management plan, two extremes that depend on whether the patient is able to manage a problem independently or needs help from a caregiver.

A third key process involves implementing the personal care plan, which implies coordination among providers and staff within the primary care setting (internal coordination) as well as between the primary care environment and the rest of the health-care system and community resources (external coordination). Because some vulnerable elders and/or caregivers are able to coordinate parts of their own care, primary care clinicians and staff take on a varying degree of responsibility for care coordination according to patient need.

PRACTICE IMPROVEMENT STRATEGIES

Table 1 (organized according to the conceptual framework in Fig. 1) provides a set of resources and strategies that primary care clinicians may find helpful in restructuring their practices to better serve vulnerable elders. Below we elaborate on these resources and strategies.

Table 1.

Approaches to Restructuring Primary Care to Serve Vulnerable Elders

| Structural element | Approach to restructuring |

|---|---|

| Delivery models | |

| Co-management | A nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA) internal to the office practice can co-manage chronic conditions common in older adults (e.g., falls, incontinence, dementia, heart failure, and depression) directly with a primary care clinician or a small group of primary care clinicians. Visits to the NP or PA are earmarked to address a specific chronic condition or conditions and use structured visit notes appropriate to the condition being addressed31 |

| Nurses, social workers, or psychologists (internal or external to a practice) receive additional specialized training in working with vulnerable elders.15,18,32 These professionals then provide support to a group of primary care clinicians in assessing patients’ and caregivers’ needs, in coordinating care, and in counseling patients or family members about chronic conditions | |

| An NP/social worker team coupled to a geriatrics interdisciplinary team can provide a high level of external support to the primary care clinician in managing care for low-income vulnerable elders14 | |

| Augmented primary care | Provide enhanced decision support for clinicians and new roles for office staff (both check-in staff and those who perform pre-examination vital signs – medical assistants or nurses) in screening for and performing basic assessment for chronic conditions.16,17 See “Flow of Authority” and “Clinical Information Systems/Decision Support” in this table for details |

| Internal resources | |

| Physical plant | An adjustable-height exam table33 facilitates a good physical examination of a vulnerable elder |

| A small amplifier with microphone and headphones34 enables better communication with patients who have hearing loss | |

| An adjustable walker can be used to check for improvement in gait and balance in response to an assistive device,35 thereby determining whether a prescription for a walker is appropriate | |

| A bladder ultrasound machine36 provides non-invasive post-void residual measurements in elders with urinary symptoms, easing the detection of urinary retention | |

| Electronic patient questionnaires allow patient data to be gathered in the waiting room or remotely37 | |

| People | |

| Staffing | General clinician/staff education on communicating with vulnerable elders (e.g., for hearing loss, speak slowly and clearly)38 can improve patient satisfaction |

| Flow of authority | A teamlet physician/nurse model with the nurse handling bulk of care coordination22,23 can help offload physicians to allow more time for medical decision-making |

| Empower the registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, or medical assistant who checks patient in through delegation of clinician tasks in specific scenarios (e.g., orthostatic vital signs in patients with a recent fall, cognitive evaluation for patients with a memory complaint)16,39 | |

| Hold brief team meetings to discuss complicated patients40 | |

| Communication | Use regularly scheduled combined clinician/staff meetings for solving problems that emerge within the practice40 |

| Use a secure website for exchanging patient-related information (e.g., related to a medication change) between the primary care office and other clinicians41,42 | |

| Develop a post-visit summary template for patients: this summary can be on paper or via a web-based patient portal available to patient and family (if patient authorizes).26 A post-visit summary may help patients in adhering to recommendations | |

| Workflow management system | |

| Clinical information systems/decision support | Use structured visit notes for paper or electronic health records, including clinical reminders and condition-specific order sets where applicable, to guide clinicians on appropriate data collection for geriatric syndromes17,31 |

| Take advantage of pre-visit questionnaires (new visit and follow-up) to decrease data gathering needs while clinician and patient are face-to-face31 | |

| Employ digital pen/paper/smart form technology to capture questionnaire information (e.g., PHQ-2) directly from paper into the electronic health record to avoid duplicate data entry43,44 | |

| Patient (and caregiver) – clinician communication systems | Use secure electronic communication between patients and clinicians45 |

| Dictate directly to e-mail to speed e-mail responses to patients46 | |

| Administrative systems | Try “block” scheduling to handle patients with predicted late arrival times.47 For example, block a 1-h time period for three patients at the start of an afternoon clinic, and ask all three to arrive at the clinic start time. Then see these patients on a first-come, first-served basis. Clinic may be more likely to start on time (and therefore run on time) using this system |

| Consider open access scheduling to improve same-day access.48 (However, see also reference 49) | |

| Community linkages | Ensure easy access for clinicians to community resource handouts and required forms for mandatory reporting (e.g., to Department of Motor Vehicles, Adult Protective Services).50 Forms may be printed from the electronic health record, available as links on the primary care office website, or placed in examination rooms |

| Develop formal partnerships with community programs to improve patients’ access to community resources51 | |

| Housing | In-home sensor technology allows remote detection of a change in a vulnerable elder’s activities of daily living.52 This could then prompt a response from caregivers or the primary care office |

| Personal care | Online resources to find a caregiver may be useful for vulnerable elders and their families53,54 |

| Health promotion and disease-specific | Computer-assisted personal exercise may be appropriate for cognitively intact elders55 |

| Group exercise programs may benefit vulnerable elders across a range of function.50 Exercise ranges from high intensity to low intensity (such as chair exercises) | |

| Caregiver support groups for vulnerable elders with Alzheimer’s disease and their families56 complement clinicians’ skills in diagnosis and treatment |

Delivery Models

Two primary care delivery approaches exist for direct care of vulnerable elders. One strategy is the co-management model, in which the primary care clinician shares responsibility with another clinician (or care team) with additional expertise in caring for vulnerable elders.14,15 In this model, the primary care clinician refers patients to the vulnerable elder expert or team for a one-time consultation or for ongoing management. For example, Ms. M could be referred to a geriatrician for further evaluation of memory loss and, if indicated, further assessment of her need for community supports. For the co-management model to be effective, clinicians caring for vulnerable elders need to create efficient access to additional clinical experts and supporting staff as well as community linkages. These additional resources could include geriatricians, nurse specialists, case managers, social workers, rehabilitation therapists, mental health counselors, home health agencies, and a network of referrals to high-quality community organizations.

The other care delivery approach is intended for small primary care practices and other settings in which there may be no local expert in vulnerable elders. In such settings, augmenting the capacity of primary care clinicians to handle the needs of vulnerable elders may be the best solution. Paper-based or computerized decision support for problems typical of vulnerable elders, with prompts to the clinician about appropriate diagnostic and management approaches, may be the most relevant approach.16,17 For Ms. M, a structured visit note guiding the primary care clinician through appropriate evaluation of memory loss may be the best strategy.16 Although small primary care practices are unlikely to have in-house case managers or social workers to help with linking patients like Ms. M to appropriate community resources, modern methods of collaborative work may offer solutions that do not require hiring new staff, such as using electronic/video linkage to social workers at community agencies.18

Physical Structure of the Primary Care Clinic

Changes to interior design and architecture can help primary care providers optimize the care of vulnerable elders, by shaping how patients interact with staff and clinicians in the primary care setting, and how staff and clinicians interact with each other. For example, a physical layout that allows easy access of a wheelchair and permits multiple family members to remain in the examination room may promote better communication among the patient, surrogates, and providers. A fixed-height standard examination table may discourage providers from conducting a thorough physical examination of a patient with decreased mobility like Ms. M, who cannot easily transfer from a chair to the exam table.19

Clinic Staff

Staff training specifically for vulnerable elders (speaking slowly and clearly, for example, for vulnerable elders with high-frequency hearing loss) may enhance the interaction of people in the office with vulnerable elder patients. Beyond training, the flow of authority among people in the office influences the productivity of the relationships among these individuals, and ultimately relationships with patients. Traditionally, primary care offices have used a “top-down” decision-making structure, but some evidence suggests that more collaborative decision-making structures are associated with better patient outcomes.20,21 In the office setting, a collaborative relationship between primary care clinician and nurse or medical assistant (clinician/nurse “teamlet”) constitutes the core of a successful primary care team.22,23

How members of primary care teams communicate with one another will influence the team’s success. Communication among team members may be formal in one environment, with routinely scheduled meetings (e.g., at the beginning of a clinical session), or very fluid, with “mini-huddles,” discussions occurring in hallways driven by immediate concerns. Communication may occur via multiple modes, including posting to a shared secure site on the Internet, e-mail, phone, written, or in-person communication. New technologies are emerging that can enable Ms. M, authorized family members, her primary care physician and nurses, and her rheumatologist to communicate electronically about Ms. M’s care.24,25 Good flow of information consists of creating a routine to ensure that all important information is mutually available to the patient, caregiver, and relevant members of the team. One such routine could include routine generation of post-visit summaries that embody the plan verbally agreed upon by patient and clinician at the visit.26 More generally, creating a communication routine means ensuring a mutual awareness among parties to communication regarding the time and frequency with which information should be shared, who the senders and recipients of the information should be, the methods (e.g., written versus verbal) by which information will be transmitted, and what content should be conveyed.

Workflow Management

A workflow management system is a method of keeping track of “a collection of tasks organized to accomplish some business process.”27 During an office visit, paper or computerized templates for geriatric syndromes (such as falls or incontinence) may help create a standard workflow for the history, physical examination, assessment, and plan.16,17 Computerized templates can use a modular design, allowing the clinician to adapt the standard workflow to the individual patient.17 Post-appointment order sheets, which provide a checklist of standard laboratory tests, procedures, and referrals that a clinician may order after seeing a patient, are also a workflow management system. These order sheets may help streamline a patient’s check-out process after the encounter with the provider is completed.22

Certain heuristics may help guide efforts to redesign workflow.28 For example, the “parallelism” heuristic asserts that some tasks are better performed in parallel rather than serially.28 Pre-visit questionnaires take advantage of this heuristic, because using a pre-visit questionnaire allows data-gathering to occur simultaneously with the clinician’s activities in caring for other patients, rather than having to be sequenced into the clinician’s activities once the patient is in the examination room. Other redesign heuristics include automating tasks where possible (e.g., using digital pen and paper to automatically import paper-based questionnaire answers into electronic format), empowering staff to complete tasks previously performed by clinicians (e.g., memory testing on patients with possible cognitive impairment),29 or designing specific workflows to have available for particular cases (e.g., condition-specific progress note templates).28 Because patients and caregivers often initiate workflow for a primary care practice, they are an extended part of the primary care team; electronic patient-clinician communication that automatically routes patient queries to the appropriate destination (be it clinician, staff, or pharmacy) may thus represent an enhancement to a practice’s work processes.30 Dictating directly to e-mail is a workflow enhancement that may make electronic communication easier for clinicians.

Administrative systems are an important element of daily workflow. For example, patient flow depends on how patients are scheduled: for vulnerable elders who are at risk of arriving late due to dependence on others for transportation, block scheduling (e.g., scheduling three patients to be seen within a given hour rather than scheduling each patient for a unique 20-min slot) may be valuable.

Community Linkages

A broad array of community linkages supports vulnerable elders, extending into multiple different domains of the private and public sectors. An older adult wanting to maintain balance and strength could be referred to a Tai Chi class at a local senior center, or an individual who wants to stop smoking could be referred to a smoking cessation hotline telephone number. Vulnerable older patients who need assistance with activities of daily living may be linked to specialized housing (assisted living, dementia care facilities), personal services (home-delivered meals, transportation), or group activities (adult day health care). Clinics may strengthen these linkages in a variety of ways (e.g., paper lists of community contacts, websites with information about community linkages that patients and/or caregivers can access, formal partnerships between clinics and community programs).18 Developing and maintaining these linkages require a substantial amount of up-front investment to identify reliable resources. Local community agencies and professional organizations may have a role in creating centralized repositories of information for primary care practices to use.

IMPLICATIONS

In this article we identify ways a primary care clinic can retool to improve quality of care for vulnerable elders. One problem is that despite their growing numbers, vulnerable elders currently represent only 4–8% of an average primary care clinician’s 2000 patient panel. In such circumstances, community linkages may play an increasingly important role in augmenting the basic capabilities of primary care practices to cope with vulnerable elders’ specific needs. Important questions for future research include how to improve the strength of linkages between primary care and community resources, and how to evaluate the quality of those community resources, so that clinicians can provide guidance to their patients about the best choices.

SCENARIO RESOLUTION

You, as the clinician caring for Ms. M, work in an environment where the co-management model is not feasible, because no geriatrician practices are available within a 100-mile radius — too far for Ms. M’s daughters to drive Ms. M. However, you have augmented your primary care resources to care for vulnerable elders. Using a structured visit note for dementia, you determine that Ms. M has Alzheimer’s disease and discuss the implications with Ms. M and her family. At the end of your visit, you refer Ms. M and her family to the nearest Alzheimer’s Association chapter for further telephone support. Although you want to improve Ms. M’s glycemic control and need to come up with a plan in concert with her rheumatologist, you recognize that you cannot solve all problems in one visit. You schedule a follow-up visit with Ms. M in 2 weeks.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge Linda E. Aoyama, MD, Robert H. Brook, MD, ScD, Brandon Koretz, MD, and Louise Walter, MD, for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. David Ganz was supported by the UCLA Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG028748) and is supported by the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (VA CD2 08–012–1). Shinyi Wu is supported by the Roybal Center for Health Policy Simulation funded by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG024968–02).

Disclosures Constance H. Fung is an employee of Zynx Health Inc., which develops evidence-based clinical decision support systems – including documentation templates and order sets – to help providers improve quality of care. The other authors have not identified any potential conflicts of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Support: David Ganz was supported by the UCLA Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG028748) and the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (VA CD2 08–012–1). Shinyi Wu is supported by the Roybal Center for Health Policy Simulation funded by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG024968–02). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Zynx Health Incorporated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams WL, McIlvain HE, Lacy NL, et al. Primary care for elderly people: why do doctors find it so hard? Gerontologist. 2002;42:835–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Wilson T, Holt T, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: complexity and clinical care. BMJ. 2001;323:685–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:740–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Health Administration Press; 1980.

- 6.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed]

- 7.Norris SL, High K, Gill TM, et al. Health care for older Americans with multiple chronic conditions: a research agenda. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:149–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kellerman R, Kirk L. Principles of the patient-centered medical home. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:774–5. [PubMed]

- 9.Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E, Taba S. History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1473–8. [PubMed]

- 10.Reuben DB. Better care for older people with chronic diseases: an emerging vision. JAMA. 2007;298:2673–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Beran MS, Laouri M, Suttorp M, Brook R. Medication costs: the role physicians play with their senior patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:102–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Reuben DB. Saving primary care. Am J Med. 2007;120:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Donabedian A. Promoting quality through evaluating the process of patient care. Med Care. 1968;6:181–202. [DOI]

- 14.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:2623–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, et al. Guided care for multimorbid older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Reuben DB, Roth C, Kamberg C, Wenger NS. Restructuring primary care practices to manage geriatric syndromes: the ACOVE-2 intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1787–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Fung CH. Computerized condition-specific templates for improving care of geriatric syndromes in a primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:989–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:713–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Winters JMW, Story MF, Barnekow K, et al. Problems with medical instrumentation experienced by patients with disabilities in: human factors and ergonomics society annual meeting proceedings; 2004: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 2004. p. 1778–82.

- 20.Safran DG, Miller W, Beckman H. Organizational dimensions of relationship-centered care. Theory, evidence, and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1)S9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA. 2004;291:1246–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Sinsky CA. Improving office practice: working smarter, not harder. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:28–34. [PubMed]

- 23.Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:457–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wallace PJ. Reshaping cancer learning through the use of health information technology. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:w169–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Stone JH. Communication between physicians and patients in the era of E-medicine. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2451–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Tang PC, Newcomb C. Informing patients: a guide for providing patient health information. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5:563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Georgakopoulos D, Hornick M, Sheth A. An overview of workflow management: From process modeling to workflow automation infrastructure. Distributed and Parallel Databases. 1995;3:119–53. [DOI]

- 28.Reijers HA. Design and control of workflow processes: business process management for the service industry. Chapter 6: heuristic workflow redesign. Berlin: Springer; 2003.

- 29.Borson S, Scanlan J, Hummel J, Gibbs K, Lessig M, Zuhr E. Implementing routine cognitive screening of older adults in primary care: process and impact on physician behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Liederman EM, Lee JC, Baquero VH, Seites PG. Patient-physician web messaging. The impact on message volume and satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:52–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Medicare Exam Office Forms. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.geronet.ucla.edu/centers/acove/office_forms.htm.)

- 32.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ritter 222 Barrier-Free Examination Table. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.midmark.com/medical_product.asp?iProductID=255&HierarchyID=372.)

- 34.POCKETALKER PRO System with HED 021 Headphone. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.williamssound.com/productdetail.aspx?product_id=94.)

- 35.Dual-Release Walker with 5″ Fixed Wheels. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.invacare.com/cgi-bin/imhqprd/inv_catalog/prod_cat_detail.jsp?s=0&prodID=6291-5F&catOID=null.)

- 36.BladderScan. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.dxu.com/bladderscan_index.htm.)

- 37.Instant Medical History. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.medicalhistory.com/home/index.asp.)

- 38.Quick Guide to Health Literacy and Older Adults. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.health.gov/communication/literacy/olderadults/default.htm.)

- 39.Glasgow RE, Davis CL, Funnell MM, Beck A. Implementing practical interventions to support chronic illness self-management. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:563–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Stewart EE, Johnson BC. Improve office efficiency in mere minutes. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:27–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Microsoft Office SharePoint Server 2007. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.microsoft.com/Sharepoint/default.mspx.)

- 42.Google Groups. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://groups.google.com/.)

- 43.Digital Pen Systems. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.digitalpensystems.com/.)

- 44.Forms Automation (Digital Pen & Paper System). (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.formationsys.com/.)

- 45.RelayHealth. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.relayhealth.com/.)

- 46.Dragon NaturallySpeaking. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.nuance.com/naturallyspeaking/.)

- 47.Penneys NS. A comparison of hourly block appointments with sequential patient scheduling in a dermatology practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:809–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Murray M, Bodenheimer T, Rittenhouse D, Grumbach K. Improving timely access to primary care: case studies of the advanced access model. JAMA. 2003;289:1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Mehrotra A, Keehl-Markowitz L, Ayanian JZ. Implementing open-access scheduling of visits in primary care practices: a cautionary tale. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:915–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Eldercare Locator. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.eldercare.gov/Eldercare/Public/Home.asp.)

- 51.Wisconsin Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.fammed.wisc.edu/innovation-outreach/wiphl.)

- 52.Continua Health Alliance. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.continuaalliance.org/use_cases/elderly_monitoring/.)

- 53.ElderCarelink. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.eldercarelink.com/.)

- 54.AssistGuide Information Services. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.agis.com/.)

- 55.Wii Fit. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.nintendo.com/wiifit/launch/?ref=.)

- 56.Alzheimer’s Association. (Accessed August 15, 2008, at http://www.alz.org/index.asp.)

- 57.Cretin S, Shortell SM, Keeler EB. An evaluation of collaborative interventions to improve chronic illness care. Framework and study design. Eval Rev. 2004;28:28–51. [DOI] [PubMed]