Abstract

Calls for institutional investors to divest (sell off) tobacco stocks threaten the industry's share values, publicise its bad behaviour, and label it as a politically unacceptable ally. US tobacco control advocates began urging government investment and pension funds to divest as a matter of responsible social policy in 1990. Following the initiation of Medicaid recovery lawsuits in 1994, advocates highlighted the contradictions between state justice departments suing the industry, and state health departments expanding tobacco control programmes, while state treasurers invested in tobacco companies. Philip Morris (PM), the most exposed US company, led the divestment opposition, consistently framing the issue as one of responsible fiscal policy. It insisted that funds had to be managed for the exclusive interest of beneficiaries, not the public at large, and for high share returns above all. This paper uses tobacco industry documents to show how PM sought to frame both the rhetorical contents and the legal contexts of the divestment debate. While tobacco stock divestment was eventually limited to only seven (but highly visible) states, US advocates focused public attention on the issue in at least 18 others plus various local jurisdictions. This added to ongoing, effective campaigns to denormalise and delegitimise the tobacco industry, dividing it from key allies. Divestment as a delegitimisation tool could have both advantages and disadvantages as a tobacco control strategy in other countries.

Keywords: divestment, institutional investing, tobacco industry finances, tobacco industry counter‐advocacy, tobacco industry documents

Calls for institutional investors to divest (sell off) tobacco stocks began to gain traction in US tobacco control circles in 1990.1,2,3 Although there had been earlier tobacco industry divestment efforts,1,4,5 several circumstances, including the rise of the socially responsible investment movement, increasing litigation against major tobacco companies, and an increasing emphasis on tobacco industry delegitimisation as a tobacco control strategy created a climate within which tobacco divestment was open for serious discussion. Divestment advocates framed the issue as one of responsible social policy, focusing on the ethical disconnect involved in profiting from such a health‐destroying product. When the industry responded by framing refusal to divest as a matter of responsible fiscal policy, advocates replied with arguments about the increasing lability of tobacco industry finances in the face of ongoing litigation and proposed government regulation, adopting the industry's preferred framing while stressing a different solution.3 As state attorneys general began suing the industry to recover smoking‐related Medicaid costs in 1994, advocates enlarged their frame to highlight the contradictions arising from state justice departments suing the industry, and state health departments expanding tobacco control programmes, while state treasurers invested in tobacco companies.6,7 Each of these frames entailed certain scenarios, privileged some authorities over others, and excluded or included varying decision‐making criteria.8,9,10,11,12

For some institutions, divestment went no further than privately reconciling missions with investment portfolios, while others intended to be social exemplars. Some tobacco control advocates saw divestment as a way to increase the public isolation of the tobacco industry, divide it from traditional financial and political allies,3,13 and further campaigns to denormalise smoking and delegitimise the industry.2 As Philip Morris (PM) documents show, as early as 1993, the tobacco industry expressed fear that a divestment movement might interfere with its ability to raise investment capital, and/or increase its growing public stigmatisation.2,14 In 1996, PM strategic fiscal issues manager John Dunham observed that industry‐targeted divestment “Labels the company as being different from others — a rogue”,15 showing that divestment efforts were impacting delegitimisation.

Previous research using tobacco industry documents has shown how PM stymied divestment at medically prestigious universities.2 This study describes PM's role in combating divestment by more financially significant government funds. It demonstrates how the tobacco company countered divestment advocates' framing of the issue, considers the role of policy champions, and examines the future implications of divestment as a tobacco control strategy.

THEORETICAL CONCERNS

Framing has been defined as “ select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation”.8 Framing defines both the issues themselves and the parameters within which it seems reasonable to think about issues. Framing may be a deliberate effort to promote a particular viewpoint, or it may represent a largely unconscious selectivity: whether conscious or unconscious, how issues are framed influences whether issues are seen as problems and what solutions are viewed as likely to be effective.16 Through case studies related to public funds divestment, we illustrate how divestment supporters and foes both relied heavily on framing the issue in terms of responsibility, and how divestment succeeded, where it did, largely through the efforts of policy champions.

METHODS

Between 17 October 2002 and 18 October 2005, we searched previously undisclosed tobacco industry documents, made public under State of Minnesota v. Philip Morris, Inc. et al,17 and the 1998 US Master Settlement Agreement (MSA),18 and posted electronically as a result of the latter. We searched the electronic documents archives of the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library at the University of California, San Francisco (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/), the seven tobacco industry defendants, and Tobacco Documents Online (http://tobaccodocuments.org/).

Using a snowball sampling approach,19,20 we expanded our search from the keywords “divestment”, “disinvestment”, and “divestiture” to the names of individuals and organisations involved in divestment activities, corporate financial documents that tracked and analysed institutional investing, and the “File areas” of key industry executives in legal, corporate, media, and financial affairs. We identified and analysed more than 1100 relevant industry documents, which we cite here representatively rather than exhaustively. (All but 19 of these documents came from PM files; thus what we know about divestment from the industry side is largely confined to this company.) We also reviewed contemporaneous news accounts and other materials related to institutional investment in, and divestment from tobacco.

To highlight key strategic and tactical issues in the struggle to control divestment framing, we compiled three case studies. We gathered additional information on California divestment from three electronic sources: the Legislative Council's Official California Legislative Information (http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/), and two sites of the Secretary of State—California Automated Lobbying And Campaign Contribution & Expenditure Search System (Cal‐Access) (http://cal‐access.ss.ca.gov/), and the Political Reform Division (http://www.ss.ca.gov/prd/). We also used electronic sources and personal interviews to supplement more limited case studies of divestment issues in the states of North Dakota and Washington.

In addition, we interviewed divestment advocates and observers regarding their perceptions of events. We reviewed a detailed study of the history and economics of institutional tobacco investing and divestment,1 and supplemented this through discussions with public fund investment professionals.

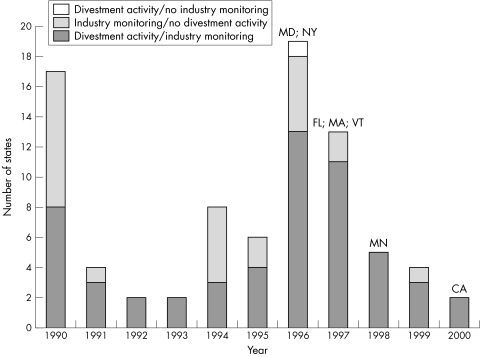

Drawing on findings from the corporate documents, we constructed a chronology/geographic distribution of industry‐monitored divestment and counter‐divestment activity (fig 1), as well as a table of industry strategies for managing divestment threats (table 1). This study is part of a larger project documenting tobacco industry responses to public health campaigns that focus on the industry's activities.

Figure 1 US state level divestment. Named states indicate successful divestments. MD, Maryland; NY, New York; FL, Florida; MA, Massachusetts; VT, Vermont; MN, Minnesota; CA, California.

Table 1 Philip Morris (PM) anti‐divestment campaign strategies.

| Gathering intelligence | Planning/organising | Reshaping the environment |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Monitoring activists: | 7. Budgeting for divestment activities: | 13. Framing divestment discussions: |

| Tobacco control/socially responsible investing conferences | Reactive planning | Continuously updated/edited counter‐divestment position paper |

| Press releases/ press conferences | Strategic planning | Computerised state‐specific talking points |

| Publications/e‐lists | 8. Counter‐divestment staffing: | Articles in professional publications |

| Correspondence with institutional investors | Reactive/ad hoc staffing | Mass media publications: letters to the editor, articles, op/eds |

| Media reporting on “antis” activities | Organised divestment team/task force | State‐specific “Commitment to jobs and economic growth” |

| 2. Tracking divestment discussions/actions: | Divestment status reports | Mass media advertising of economic contributions |

| Divestment tracking charts | 9. Preparing staff briefing materials: | White papers on related subjects: |

| Government affairs weekly report | Corporate issues manual and “Issues and answers” | – losses due to South Africa divestment |

| Lobbyist/consultant reports | Collected media reports on divestment | – superiority of PM returns over other options |

| Mass media reports, media RFIs | Divestment issues handbook | – portfolio return compared with/without PM |

| 3. Monitoring institutional investments: | Divestment questions and answers | 14. Exerting personal influence on decision‐makers through: |

| Periodic holdings/turnover reports | 10. Briefing “local legislative consultants” | “Old boys:” |

| Identification/analysis of sell‐offs | Regional/local as needed | – alumni |

| 4. Identifying potential allies including: | 1996 Government Affairs Conference | – overlapping board memberships |

| Public policy groups | 11. Claiming privilege for internal communications: | – political/social connections |

| Investment policy groups | Attorney/client communication | Top echelon executives: |

| Stakeholders not previously friendly: | Attorney work‐product | – divestment‐specific contacts |

| – “organised labour” | Trade secrets | – in the ordinary course of business |

| – “teachers” | 12. Monitoring corporate activities for compliance with: | – management response video |

| – “government employees” | “lobbying regulations” | – rapid response teams |

| – “college professors” | “the Securities and Exchange Commission” | Peers/professionals: |

| – “the elderly” | “other…federal, state and local laws” | – institutional investors |

| 5. Contracting “third party research firms” to assess potential divestment sites | – outside analysts | |

| 6. Opinion polling “elected officials and the general public” | – legal/fiduciary authorities | |

| Local operatives and lobbyists | ||

| 15. Mobilising “third parties” | ||

| “Groups which, in the past, have not had favorable opinions of the company” | ||

| “Third party public policy and investment policy groups” | ||

| “Responsible investing' Internet page” | ||

| “Third party investment advisors” | ||

| 16. Planning legislation to alter state investment rules/monitoring state investment rule law‐making |

RESULTS

Background

Tobacco stock divestment initiatives arose from multiple sources over an extended period of time.1,4 During the 1980s, social welfare foundations (for example, Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, Rockefeller Family Fund, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) and health organisations (for example, American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, World Health Organization) began divesting, mostly to reconcile their institutional finances with their stated missions. Until the American Medical Association's explicit call for medical school divestment in 1987, divestment mostly remained a “quiet” phenomenon. Activist‐driven, publicly conducted divestment campaigns accelerated in 1990, focusing first on academia, and later on large private and public investment and retirement funds.1,2 Between 1990 and 2000, divestment discussions drawing media attention took place in at least 25 states. However, only seven states (plus a number of counties and cities) partially or fully divested (fig 1).

Divestment as a Philip Morris issue

Although it might seem that smaller or less profitable tobacco manufacturers would suffer most from campaigns to destabilise stock values, our research suggests that PM dominated counter‐divestment activities from the beginning. Arguably, the company actually had the most at stake.

By 1990, PM controlled a 42% share of the US cigarette market, while that of RJ Reynolds, its closest competitor, had fallen to 29%.21 As the most visible symbol of the US tobacco industry, PM became a lightning rod for industry‐focused advocacy campaigns. Although RJ Reynolds and others were also subjected to these actions, most attention was directed at PM.

PM was also the most exposed to a campaign targeting corporate stock because of its large number of outstanding common shares. Of the total market capitalisation of the four leading US cigarette manufacturers, 68% was credited to PM in the Master Settlement Agreement of 1998.18 (In 1990 and most of 1991, at the outset of the divestment campaigns, RJ Reynolds was not even being publicly traded.) Consequently, even small losses in the value of PM stocks would have totalled large absolute dollar amounts. Geoffrey Bible, who led the company through most of the counter‐divestment period, was elevated to CEO in 1994 to restore institutional shareholder confidence in faltering PM stock prices.22 Bible and other PM executives also had a large personal stake in healthy prices. For example, as of 31 December 1996, Bible and Chief Counsel Murray Bring together owned more than 1.35 million PM shares valued above $66 million, and held exercisable options on an additional 1.1 million shares worth a further $54.4 million.23

While PM fought public funds divestment from its inception,24,25 the company's resistance crystallised in 1996–97, as divestment advocacy was boosted by the growing number of states joining the Medicaid‐recovery lawsuits.26 PM had initially acted jointly with industry allies25, but its 1996–97 counter‐divestment strategic plan explicitly sought to “focus on the company, not on the industry. The issue is not tobacco, but the company as an investment vehicle”.27 By taking this position, PM could sharpen its fiscal responsibility framing, while side‐stepping an unwinnable argument about the health consequences of smoking. Distancing itself from the rest of the tobacco industry was also part of a larger plan to remake the company's poor public image.28

PM began with two distinct advantages: those who would make decisions for or against divestment were mostly professionally pre‐committed to a fiscal rather than a social perspective, and many believed their funds had been harmed by South Africa‐related divestment in the 1980s.1 Where tobacco control advocates drew on South African divestment as an organising paradigm, PM constantly reminded decision‐makers of the purported costs/losses of the earlier divestment.25,29,30,31,32

Philip Morris' counter‐divestment strategies

PM's counter‐divestment strategies encompassed three domains: (a) intelligence‐gathering; (b) internal resource organising; and (c) shaping the external environment (table 1). These are typical approaches to corporate issues management.33 In this paper, we focus chiefly on the third: PM's effort to control the external environments in which public funds divestment was being debated.

Intelligence gathering

Top PM executives closely monitored divestment advocates, institutional investors, and third party allies. PM's corporate secretary attended a 1990 Social Investing Conference, reporting to senior management on the presentations of leading divestment advocates.34,35,36 PM's CEO, chief counsel and corporate secretary carefully scrutinised large institutional sell‐offs,37,38,39 and tracked institutional investors through mutual fund equity reports and summary updates.40,41

Internal resource organising

Where early budgets rose and fell in correspondence with perceived divestment threats,14 the 1996–97 strategic planning process institutionalised a standing executive “divestment task force,” assigning responsibilities for “overall policy”, “day to day operations”, and “general communication with the public and media”.42 The company developed staff briefing materials that posed provocative questions like: “Isn't it appropriate for government and private institutions to divest their holdings in a death‐dealing industry?” The materials instructed staff to respond that divestment‐contemplating states never offered to forgo “the millions of dollars tobacco raises for them in tax revenues” and that governments had “a fiduciary obligation to maximize their investments”.43 Through briefings conducted at state,44 regional,15 and national levels,45 PM informed lobbyists and consultants of “tools available to mitigate the possibility of divestment in their states”,42 including “expert witnesses, a response team, and written back‐up such as white papers and talking points”.45

Shaping the external environment

PM sought to reshape the environment within which divestment could be considered in two ways: by reframing the terms of the debate, and by restricting the legal opportunities for divestment. The company's “targeted audiences” included officeholders and fund trustees, financial specialists, third party allies, the general public, and all types of media.42

Tobacco control advocates emphasised the need for social responsibility, initially pointing to the “ethical contradiction” of “public institutions and nonprofits” using tobacco “profits…to pursue their agendas”.13 Later, they argued that tobacco investments would “undermine the health and educational programs of the state: tobacco investments will remain safe and profitable only if these efforts fail”.7 They added the fiscal argument that “the future profitability of tobacco is now very much in doubt in the face of smoking restrictions, proposed FDA regulation and cigarette excise tax policies”, but insisted that “[t]he most compelling reason for divesting tobacco securities is that these investments are morally indefensible”46 [italics in the original].

PM unremittingly countered that the sole duty of fund decision‐makers was fiscal responsibility. “Investment policy should not be used to achieve social goals,” PM insisted. “The merits of political causes should be decided in the political arena not in the financial markets.”47

PM insisted to the public and to investment decision‐makers that it was not just a tobacco company but a diverse consumer products company, that investing in PM's high‐return securities was prudent for pension beneficiaries, taxpayers and local economies, and that to terminate such investments would be irresponsible, expensive, and possibly illegal.48,49 Through the personal and professional interactions of top executives,50,51 field operatives and agents,52,53 and third party allies,54,55 PM disseminated a continuously updated counter‐divestment position paper,30,32,48,56 state‐specific talking points,49,57,58 commentaries in professional newsletters and journals,59,60 and mass media letters to the editor, op‐eds, and articles.61,62,63,64

How or whether PM acted on its goal to restructure the legal environment to all but bar divestment by public funds is less clear, although there is no question about the company's intentions. “Long term efforts”, its 1996–97 counter‐divestment strategic plan emphasised, should “focus on eliminating the opportunities to successfully introduce divestment initiatives, especially in the case of public pension funds”.42 The company would “work with legislators to pass…investment laws” to “limit the ability of fund managers or trustees to use anything but financial/economic considerations for investment decisions”.42 Documents show that PM monitored legislative activities that would have served these purposes in at least three states.65,66,67,68

The three case studies that follow demonstrate both the vigour and the persistence with which PM fought the divestment issue. They illustrate key strategies the company employed in reframing the terms of the debate, and show that PM followed proceedings that could restrict the legal possibilities for divestment. Finally, they illustrate the important role of policy champions.

California: 1990–2000

California's public retirement system funds—CalPERS (public employees) and CalSTRS (state teachers)—are the largest in the United States, comprising more than 11% of an estimated $2.7 trillion in public funds.69 CalPERS was recently valued at $181.2 billion,70 and CalSTRS at $124.3 billion.71 PM's California counter‐divestment strategies centred on blocking divestment legislatively, but ultimately failed before the executive authority of a determined state treasurer.

PM initiated monitoring for California divestment activity in June 1990.72 When California Health and Human Services director Kenneth Kizer publicly urged divestment in January 1991, a copy of the CalPERS executive director's negative response to Kizer was faxed to PM within a day of its sending to Kizer.73 The California Chamber of Commerce's blasting of Kizer's proposal as “the worst example of the use of public pension funds to direct social policy” was also quickly reported to PM.74 Kizer's proposal went nowhere, but the California Tobacco Control Program's assertive advertisements highlighting industry behaviour began to radically reshape Californians' perceptions of the tobacco industry.75

In February 1996, divestment legislation introduced into the state assembly (AB 3445)76 was opposed by CalPERS, CalSTRS, the California Retired Teachers Association, and the state Chamber of Commerce and Manufacturers Association, as well as the Smokeless Tobacco Council and Dowd Relations. Identified by the Los Angeles Times as a “lobbyist for the Tobacco Institute”, Phil Dowd's rhetoric mirrored PM's. “Pension funds are not play toys to be manipulated for political or social purposes,” he told the assembly.77 PM observed that the bill was “killed” in committee two months later.78

In the following legislative session, the new Democratic majority held a hearing to “investigate the need for alternative investment strategies by the state pension funds regarding their tobacco holdings”.79 Although repeatedly requested to send representation,80,81,82,83,84 PM declined to do so officially.85 However, The Dolphin Group, which functioned as a third party agent for the tobacco industry in California,75 reported back to PM on the hearings.86,87

Three divestment bills entered before the 1997–98 California legislative session ultimately failed to pass out of the Assembly Appropriations Committee.88,89,90 Again, they met with opposition from the California Retired Teachers Association, Cal‐Tax, the Smokeless Tobacco Council, the Tobacco Institute,91 and CalPERS.89 At the very least, the Assembly leadership did not press as hard as it might have to move the bills forward.

During this period, PM created a series of 4–7 page, computer‐updatable, mini‐position papers tailored for use before legislatures and pension boards.49,57,58 Each contained boilerplate promoting the company's outstanding share returns and asserting its “slippery slope” argument: once exclude tobacco investments and there would remain no defence against other divestment activism. Each also contained state‐specific sections addressing fiduciary responsibility laws; lost opportunity and added transaction costs for excluding tobacco investments; projected tax and/or pension fund contribution increases due to investment losses aggravated by aging populations; and PM's contributions to the local economy in purchases, excise taxes and charitable giving.

PM's 1998 California talking points quoted the state's constitution to emphasise two basic principles of financial trusteeship, the prudent person rule:

The members of the retirement board of a public pension or retirement system shall discharge their duties…with the care, skill, prudence and diligence…that a prudent person…would use,

and the exclusivity rule:

The assets of a public pension or retirement system…shall be held for the exclusive purposes of providing benefits to participants.49

TI's Dowd had testified that one of the bills would violate the prudent person rule by “limiting the scope of possible investments”, and the exclusivity rule because “The state's tobacco investments are not public money. The money belongs to the pensioners”.92

This interpretation ignored a 1992 California law known to PM executives.93 Proposition 162, while intended to prevent public employee pension assets from being diverted into budget‐balancing schemes,94 also sought to protect union and retiree interests from overly narrow‐minded retirement fund boards.95 It stated that:

The Legislature may…continue to prohibit certain investments by a retirement board where it is in the public interest to do so, and provided that the prohibition satisfies the standards of fiduciary care and loyalty required.96

PM's California talking points claimed that, had California been divested between 1995 and 1998, the state would have lost $171 million in tobacco stock earnings, while incurring $700 000 in sales and replacement costs. Additionally, the company raised the spectre of a growing population of “elderly persons” requiring pension support from a shrinking “workforce”, but failed to address what percentage of either might consist of persons to whom the state was obligated.

State officials were also reminded that in 1996, PM had employed over 3000 Californians and purchased more than $1.25 billion in California goods and services (mostly through non‐tobacco businesses), and paid almost $675 million in tobacco excise taxes. PM highlighted contributions of “millions of dollars to charities in California, including major grants to the San Diego Zoo, the University of Southern California (for a crisis intervention program) and California Food Policy Advocates”.49

PM, however, may have underestimated new State Treasurer Phil Angelides, a proponent of one of the 1997 bills,97 who had expressed both financial and social concerns about tobacco investments as he campaigned for office.98,99 In December 1999, Angelides used his executive authority to make permanent a de facto moratorium on tobacco stock purchases by the California Pooled Money Investment Account (the pooled funds of smaller government entities).100 The following February, Angelides signalled his intention to use seats on the boards of CalPERS and CalSTRS to press for their divestment from tobacco as well.101 At his request, PM provided Angelides' office with the latest version of its position paper,102 and then continued to monitor his actions from both Sacramento and New York.103,104,105,106,107 Corporate headquarters' query—“what can be done with Phil?”106—met with Sacramento's less than reassuring reply: “Angelides has heard our view on this, but appears to be firmly dug in.”107

Pressed by Angelides, CalSTRS voted on 7 June 2000 to divest pending the drafting of technical authorisation criteria.108 CalPERS shortly followed.98,99,109

North Dakota: 1990–1997

PM's activities in this state illustrate how counter‐divestment advocacy was coordinated between the field and New York City headquarters, and document the strategic shift from cooperation with other tobacco interests. They demonstrate the persistence of the company's anti‐divestment focus, and show that PM was attending to legislation that could have advanced the legal restriction of public funds divestment.42

In May 1990, Stephen McDonough, the state's Preventive Health Section director, urged the North Dakota Public Employees Retirement System (NDPERS) to divest of tobacco holdings.25 Although McDonough recently described the effort as “never a real serious one”,110 PM responded seriously. In an August memo to vice‐president Wall, PM's regional government affairs director Mary Cramer laid out her actions and intentions in parallel tracks.

Locally, Cramer planned for the company's lobbyist to “talk with the NDPERS executive director…and offer the assistance of PM”. After “lobbyists representing all tobacco interests…determine[d] who has the best contacts”, they would meet with board members, and then “determine what pressure must be applied to each individual”.25

Cramer detailed actions to recruit allies. Having met with the staff representative for the North Dakota Public Employees Association, she asked headquarters for a white paper directed to unions. “I have contacted Miller Brewing,” she continued. “Several barley growers have indicated that they would do whatever necessary to assist… [W]e will work with these individuals as well as the agricultural associations.”25

Simultaneously, Cramer called upon corporate headquarters to provide counter‐divestment arguments, and to document PM's value to the state economy. “Tear Dr. McDonough's letter apart,” she demanded. “I want every fact and figure…refuted.” She asked to know how much tobacco stock “contribute[d] to the total revenue” of the retirement fund, and for a list of “other American companies…directly profiting[from]…our tobacco production”, like paper manufacturer Kimberly Clark. She requested data on the value of PM purchases from North Dakota agriculturalists— “I have been told…that we are a major purchaser of the sugar beet crop”25—and proposed a mass media campaign advertising PM's purchases of local produce.111,112

According to PM, the board referred the matter to an “Investment Subcommittee”.113 There is no evidence of the committee having acted by the next full board meeting in January 1991.

In its 1996 state overview, PM declared an “Objective[to] Defeat Divestment Issues” in North Dakota.114 PM also monitored a 1997 action in the state's legislature that bore on its plan for legally restricting divestment options.42

PM's 31 January 1997 Government Affairs Weekly Report noted the legislative introduction of “HB1092, Uniform State Laws on prudent investor act and duties of a trustee”,65 amending the North Dakota Century Code to define more specifically the responsibilities of investment fund trustees, and more strictly limit trustees' focus “solely in the interests of the beneficiaries”.115 (The bill also contained language regarding contextualization and diversification discussed more fully under the Washington case, below.) The bill was signed into law by the Governor on 26 March 1997.116

During this period, there was a national movement afoot to “replace…a patchwork of state[investing] standards with one uniform standard, with that standard being identical to the[federal] ERISA standard”.1 Uniform standards advocates insisted their only concern was to create a single, strong model of prudence and fiduciary responsibility, but such an ERISA‐like standard would have barred states from considering social issues in pension investment decisions.1 In counter‐example, California's Proposition 162 specifically permitted the legislature to restrict state investments for social/political reasons as long as it maintained standards of fiduciary care and loyalty to beneficiaries.95

Washington: 1990–2000

This case illustrates the development of state legislation that would have made divestment more difficult, or, at least, made it easier to justify continued tobacco investments. This was the kind of legislation envisioned in the tobacco company's 1996 strategic plan,42 and PM followed it closely in 1998.

As in California, PM's Washington monitoring began in 1990, well in advance of the emergence of public divestment activities.117 From 1991 through 1997, PM followed divestment discussions by the Washington State Investment Board (WSIB),113,118,119,120,121,122 and in the state legislature,123,124 preparing testimony for the latter.125 In the summer of 1997, the company drafted a state‐specific counter‐divestment position paper,126 paralleling the California one detailed above.49

Then, in January 1998, at WSIB's request,127 bills were introduced before the legislature essentially permitting WSIB to engage in less sound financial decisions that could have favoured tobacco investments. SB 6192 authorised the investment board to:

1) consider investments not in isolation, but in the context of the…fund as a whole and…an overall investment strategy.

It mandated WSIB to:

2) diversify…investments unless…the board reasonably determines that the purposes of that fund are better served without diversifying.128

PM tracked the course of the legislation from its introduction to its signing by the Governor in March.66,67,68

On the face of it, the requirements for diversification and contextualisation (considering each investment in the context of the whole portfolio) could both make divestment more difficult. As PM noted, excluding an entire industry would limit diversity,48 and as Dowd had argued, might violate the prudence principle.92 Requiring that each investment be evaluated “as part of an overall investment strategy”,128 at the same time, could vitiate arguments about the financial soundness of a particular industry. According to National Council on Teacher Retirement attorney Cynthia Moore, contextualisation was on the agenda of many public fund managers at the time. Trustees desired increased flexibility to invest in “risky” stocks if they could show their portfolios were balanced by other investments of especially low risk.129

Under rubrics like Washington's “moderniz[ing]…state law to conform to…current practices”,130 or North Dakota's aligning state standards with “modern portfolio theory”,131 a “Uniform Prudent Investor Act”, specifically intended to require diversification and contextualisation, was being circulated around state legislatures.132 Produced for the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, this model statute had been co‐authored by anti‐divestment advocate John Langbein,133 a Yale law professor who served as PM's chief counter‐divestment consultant and periodically rewrote the company's evolving “Response to divestment proposals”.48,134 The introduction of this model into Washington in 1998 (as into North Dakota during the previous year116), fitted PM's plan to restrict legislatively the divestment possibilities of public funds.42

PM tracked a 2000 Washington divestment bill (HB 2743),135,136 but it was quickly consigned to the Appropriations Committee from which it appears never to have emerged.137 The state legislative web site records no subsequent divestment attempts.138

DISCUSSION

Framing the debate

The depth of PM's concerns about divestment is evidenced by its material and manpower commitments, and the intensity and perseverance of its attention to the issue. The company sought to control how the debate was framed at two levels: (1) it argued that tobacco investments were good fiscal choices, and fiscal soundness was all that mattered; and (2) it planned to help write and pass laws barring divestment for any other than fiscal policy reasons. That divestment was eventually limited to seven states and an additional dozen or so cities and counties (for example, San Francisco39 and Denver in 1996,139 Philadelphia in 1997,140 Tucson in 1998141), suggests that PM mostly succeeded in promoting its framing.

Divestment advocates advanced their own ethical social policy frame, while also arguing that tobacco investments were no longer sound fiscal policy. They found public platforms in 25 states (and additional local jurisdictions), and they carried the field in 30% of these. In the jurisdictions where divestment advocacy succeeded, the issue was championed by at least one important political leader, and these leaders generally put forward negative fiscal as well as positive social policy frames.

While ethics‐based arguments may have created pressure on decision‐makers to undertake divestment discussions, in the end it was fiscal and not ethical arguments that moved them. Even in those instances where states elected to divest, it was arguments about the growing financial lability of the industry that carried the day. The divestment authorisation policies developed at CalSTRS and CalPERS referred to corporate bankruptcies, aggressive lawsuits, enhanced government regulations, and capital flight via institutional divestments,98 and still, the fund directors argued against divestment to the end.99

Pre‐framing the law

Investment and divestment rules for public and private funds in the United States differ substantially among for‐profit and non‐profit organisations, unions, and government entities.1 PM, however, planned to eliminate such differences and any leeway they provided. At the minimum, the company benefited from the 1990s movement to abolish such difference through the nationwide adoption of a “Uniform Prudent Investor Act”. Local proponents spoke of modernising their states' legislation, or bringing regulation into conformity with existing investment practices,130,131 but at least one co‐author of the model act was a prominent anti‐divestment theorist, and PM's chief anti‐divestment consultant. Adopting the model act would make divestment more difficult, supporting arguments that it limited diversification, while weakening arguments regarding the growing riskiness of tobacco industry investments.

The importance of policy leadership

Policy championship by at least one strong political leader appears to have played a crucial role in divestment enactment. Of the five tobacco control “poster states” (California, Oregon, Arizona, Massachusetts and Florida, the first to develop US Centers for Disease Control‐endorsed comprehensive tobacco control infrastructure142), divestment succeeded only in the three where it was actively championed by prominent political leaders: Treasurer Angelides in California97,100,101; Congressman Martin Meehan143 and eventually Treasurer Joseph Malone in Massachusetts144; and Governor Lawton Chiles in Florida.145 In Oregon, legislative divestment proposals died in committee in both 1997 and 1999.146,147 Despite PM's 1996 anticipation148 (and Tucson's 1998 action141), in Arizona, divestment does not even appear to have emerged at the state level.

Divestment also succeeded in two other states where tobacco control infrastructure was not remarkably precocious. In Maryland—the first state to fully divest tobacco shareholdings—Attorney General Joseph J Curran had been urging divestment since 1994.46,149,150 It was not until May 1996, however, when his state was on the verge of joining the Medicaid suits, that Curran carried the argument: Maryland, it was asserted, sought both to bolster the credibility of its legal position, as well as to avoid suing one of its own investments.151 Similarly, Treasurer Jim Douglas spearheaded Vermont's successful 1998 divestment, even if, as a PM consultant speculated, it was mostly to steal the issue from the Democrats.152

Ironically, divestment was delayed for two years in Minnesota, when Attorney General Hubert H Humphrey III—one of the earliest and most successful Medicaid litigants—recused himself in 1996 from being the deciding vote in favour of his state's divestment because of his lawsuit participation.153 Minnesota divestment was delayed until the settlement of the suits in the summer of 1998.154 Meanwhile New York, in the absence of a political champion, became the first state to formally limit tobacco investments in April 1996, but stopped short of actual divestment.155

Divestment as a tobacco control strategy

These efforts to promote divestment from tobacco stocks occurred during a time when the tobacco control movement was in its ascendancy. Heavy media coverage of the state attorneys general lawsuits, an activist movement increasingly focusing its attention on the tobacco industry, and increased interest in socially responsible investing as a way to bring pressure on corporate entities, shaped a context in which divestment would be taken seriously. However, as a tobacco control strategy, divestment may have both strengths and weaknesses. This study suggests that both context and leadership are critical.

Divestment's strengths include the publicity surrounding divestment initiatives, which may engage stakeholders not otherwise concerned with smoking. For example, individuals with retirement funds invested in tobacco stocks may question the long term viability of the industry or the social costs of sustaining it. Divestment builds upon and strengthens ongoing industry delegitimisation efforts by labelling tobacco products as different from, “dirtier” than other sources of profits, a prospect which PM documents indicate the company feared.15 Like campaigns for smoke‐free spaces, public funds divestment campaigns provide numerous platforms for creating delegitimisation publicity (as opposed to shareholder initiatives, which only provide such opportunities at annual, company‐controlled shareholder meetings). Such efforts have been shown to be an important part of successful tobacco control efforts, undermining the notion that the tobacco business is just like any other, while building public support for regulatory initiatives.2,156,157

However, divestment efforts may also create disadvantages for tobacco control. First, they require considerable energy and political capital; divestment will likely always be an uphill battle as it requires fund managers not only to reach decisions about tobacco investments, but may require them to adopt new criteria for decision‐making. Divestment activists have little control over the performance of tobacco stocks, which in recent years have risen steadily in what is regarded as a more stable political and regulatory environment than during the 1990s. Also, should divestment efforts result in a company deciding to go into private ownership rather than risk continued stock erosion, tobacco control advocates would lose access to valuable information about industry economics and activities, disclosure of which the U.S. requires from publicly traded companies.

Conclusion

The 1990s tobacco stock divestment movement put pressure on the tobacco industry, and caused top PM executives to expend considerable time and resources defending against it. Divestment advocacy may have been of limited success in convincing public fund decision‐makers to withdraw their funds' financial resources from the tobacco industry, but the states where divestment advocates succeeded in whole or in part were/are highly visible, often trendsetters in public health and social policymaking.

What this paper adds

While previous research using tobacco industry documents has shown how Philip Morris (PM) stymied divestment at medically prestigious universities, this study describes PM's role in combating divestment by financially significant government funds. It demonstrates how the tobacco company countered divestment advocates' framing of the issue as one of social responsibility with its own preferred framing of fiscal responsibility, considers the role of policy champions in advancing divestment actions, and examines the future implications of divestment as a tobacco control strategy.

This suggests that an important measurement of the impact of stock divestment advocacy as a tobacco control strategy may be the extent to which it is able to draw public and media attention to the destructive nature of the cigarette industry. Arguably, the industry is weakened whenever major institutional shareholders sell off their holdings, especially if this decision is publicly acknowledged. Even where divestment efforts are unsuccessful, however, they may advance public dialogue about the industry's fundamental irresponsibility in continuing to promote products that addict and kill half their long time consumers, and the imprudence of continuing to support such a business.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the members of the Tobacco Policy Research Group of the University of California, San Francisco for feedback in the development of this paper. This work was funded by the California Tobacco‐Related Disease Research Program (Award #11RT‐0139) and the National Cancer Institute (CA095989).

Footnotes

Competing interests: Both authors are employees of the University of California engaged in the study of the tobacco industry through its internal documents. The senior (second) author owns one share of Altria/Philip Morris stock for research and advocacy purposes.

References

- 1.Cogan D. ed. Tobacco divestment and fiduciary responsibility: a legal and financial analysis. Washington, DC: Investor Responsibility Research Center, 2000

- 2.Wander N, Malone R E. Selling off or selling out? Medical schools and ethical leadership in tobacco stock divestment. Acad Med 2004791017–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krevor B. Tobacco Divestment Project origins and aims. Personal communication to N. Wander. 15 Nov

- 4.Blum A, Daynard R A. A Review of divestment by medical organizations and academic institutions of shareholdings in tobacco companies. In: Slama K, ed. Tobacco and health. New York: Plenum, 19951005–1006.

- 5.[Doctors Ought to Care] DOC efforts spark major universities to divest tobacco holdings. Jul 1991/DP. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2047375692/5706. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yfp72e00 (Accessed 10 Jan 2003)

- 6.Krevor B S, Saynard[Daynard] R A. Tobacco Diversment[Divestment] Project. N327[Letter to Colorado Treasurer Schoettler raising issue of reliability and propriety of state's investments in tobacco]. 9 Dec 1994. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2045687577. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vws57d00 (Accessed 28 Apr 2004)

- 7.Krevor B S. Tobacco Diverstment[Divestment] Project. N327[Letter to Colorado Attorney General Norton raising issue of reliability and propriety of state's investments in tobacco]. 9 Dec 1994. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2045687576. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uws57d00 (Accessed 28 Apr 2004)

- 8.Entman R M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 19934351–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petruck M R L. Frame Semantics. In: Verschueren JJ‐OÖJBaCB, ed. Handbook of pragmatics. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1996

- 10.Lakoff G P. A Cognitive Scientist Looks at Daubert. Am J Public Health 200595(suppl 1)S114–S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight M G. Getting past the impasse: framing as a tool for public relations. Public Relations Review 199925381–398. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fillmore C J. Frames and the semantics of understanding. Quaderni di Semantica 19856222–254. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Advocacy Institute Smoking Control Advocacy Resource Center (SCARC) action alert issue: Shaming the shareholders: An appeal for investor responsibility. 11 May 1990. Advocacy Institute, Bates No. 2025862132/2135. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mkm61d00 (Accessed 10 Jan 2003)

- 14.[Philip Morris] Cigarette excise taxes. 24 Sep 1993. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2040714381/4405. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pri72e00 (Accessed 16 Dec 2002)

- 15.[Dunham J ] Issues Management Divestment Action Plan. 8 Jul 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078279058/9068. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fir75c00 (Accessed 13 May 2004)

- 16.Dorfman L, Woodruff K, Chavez V.et al Youth and violence on local television news in California. Am J Public Health 1997871311–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The State of Minnesota by Hubert H. Humphrey III, its Attorney General, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota, Plaintiffs, vs. Philip Morris Incorporated, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation, B.A.T. Industries P.L.C., British‐American Tobacco Company Limited, Bat (U.K. & Export) Limited, Lorillard Tobacco Company, The American Tobacco Company, Liggett Group, Inc., The Council For Tobacco Research‐U.S.A., Inc., and The Tobacco Institute, Inc., Defendants. In: United States District Court, State of Minnesota 1998

- 18.National Association of Attorneys General Master Settlement Agreement: NAAG; 1998. http://www.naag.org/upload/1032468605_cigmsa.pdf (Accessed 6 Aug 2004)

- 19.Malone R E, Balbach E D. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control 20009334–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKenzie R, Collin J, Lee K. The tobacco industry documents: An introductory handbook and resource guide for researchers. web page: Centre on Global Change and Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; 2003. http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/cgch/tobacco/Handbook%2030.06.pdf (Accessed 21 Jul 2005)

- 21.Kluger R.Ashes to ashes: America's hundred‐year cigarette war, the public health and the unabashed triumph of Philip Morris. New York: Vintage Books, 1997

- 22.[Williams I ] [How they do it at Philip Morris]. Jul 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2072810726/0729. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tas95c00 (Accessed 11 May 2004)

- 23.Holsenbeck G P. Notice of Annual Meeting of Stockholders to Be Held Thursday, 970424. 10 Mar 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2084331907/1944. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vlr80c00 (Accessed 27 Oct 2005)

- 24.Murray R W. Memorandum between Philip Morris employees memorializing legal strategy regarding stock divestiture. 31 May 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024672801/2804. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hlo12a00 (Accessed 6 Nov 2002)

- 25.Cramer M T. North Dakota divestiture. 20 Aug 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024672806/2808. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/plx36e00 (Accessed 6 Nov 2002)

- 26.Rabin R L. The third wave of tobacco tort litigation. In: Rabin RL, Sugarman SD, eds. Regulating tobacco. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001176–206.

- 27.[Dunham J ] Divestment Meeting Thursday, 960523 10:00 A.M. Conference Room 14e a Concept Proposal for a Public Information Campaign to Mitigate Calls for Divestment. 23 May 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077235301/5304. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qck62c00 (Accessed 9 May 2004)

- 28.Smith E A, Malone R E. Thinking the ‘unthinkable': why Philip Morris considered quitting. Tob Control 200312208–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.[Dunham J ] Philip Morris Divestment Issue Task Force Full Task Force 970328 3:00 – 4:30 Pm 120 Park Avenue, 14th Floor. 28 Mar 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078830830. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ycy67c00 (Accessed 25 May 2004)

- 30.[Philip Morris Companies Inc] Philip Morris Companies Inc. Position Paper on Divestment and Exclusion of Tobacco Stocks. 6 Aug 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024672693/2722. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bds61f00 (Accessed 6 Nov 2002)

- 31.Gannon F. “Tobacco project” divestment statement draft. Oct 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024672510/2519. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ins24e00 (Accessed 6 Nov 2002)

- 32.Langbein J H. Langbein revision draft. 16 Jan 1991. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2023225133/5150. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zad78e00 (Accessed 23 Oct 2002)

- 33.Heath R L. Corporate issues management: theoretical underpinnings and research foundation. In: Grunig LA, Grunig JE, eds. Public relations research annual. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, 199029–64.

- 34.[Investment Management Institute] Investment Management Institute Presents the Social Investing Conference 901206–901207[Program]. 6 Dec 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024303017/3022. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qtf34e00 (Accessed 9 Feb 2004)

- 35.[Investment Management Institute] Investment Management Institute Presents the Social Investing Conference 901206 – 901207[Roster of Attendees]. 6 Dec 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024303013/3016. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ptf34e00 (Accessed 9 Feb 2004)

- 36.Fried D. Social Investing: Tobacco Divestment Project. 14 Dec 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024303011/3012. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xgu88e00 (Accessed 9 Feb 2004)

- 37.[D. F. King & Company] Philip Morris Listing of Public Sector Positions[Bible annotations]. May 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073730124/0126. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/caz85c00 (Accessed 7 May 2004)

- 38.[D. F. King & Company] Philip Morris Listing of Public Sector Positions[ Bring annotations]. May 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073923629/3631. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xzl85c00 (Accessed 7 May 2004)

- 39.Holsenbeck G P. Public Pension Fund Ownership of Philip Morris [Bible annotations]. 10 May 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073730122/0123. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ozt42c00 (Accessed 7 May 2004)

- 40.[D. F. King & Company] Philip Morris Companies Weekly Report 960329. 2 Apr 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073730148. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gaz85c00 (Accessed 06 May 2004)

- 41.[CDA/Equity Intelligence] [D. F. King & Company]. Top 100 Institutional Holding Update for Philip Morris Cos. Jul 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2072810736/0737. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uas95c00 (Accessed 11 May 2004)

- 42.[Dunham J ] N344 [A Concept Proposal for a Public Information Campaign to Mitigate Calls for Divestment Presentation Draft]. 19 Aug 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070141007/1012. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fng47d00 (Accessed 10 May 2004)

- 43.[Philip Morris] Tobacco Issues and Answers. 1992. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2040714260/4294. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vwq74e00 (Accessed 20 Apr 2004)

- 44.Lemperes J. Update Ma & Nj. 26 Sep 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2065372663A. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/maa53a00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 45.R JG[Ramsay J], [Walls T] Twalls[T Walls] Opening Remarks to Gad Consultant Conference, 961000. Review of 960000 and Overview of Conference. 25 Sep 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2080368260/8270. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/egd75c00 (Accessed 15 May 2004)

- 46.Bailm S D, Beversdorf C A, Bhide G.et al ABYSSINIAN BAPTIST CHURCH, AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY, AMERICAN HEART ASSN, AMERICAN LUNG ASSN, AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSN, ASSN OF STATE + TERRITORIAL HEALTH OFFIC, et al. N327[Letter to NYS Comptroller Carl McCall urging that public retirement funds not be invested in tobacco stocks]. 7 Mar 1995. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2045935424/5424A. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lgr57d00 (Accessed 3 May 2004)

- 47.[Philip Morris] Generic Letters to the Editor Divestment: Divestment (4 Letters) (Narrative & Images). 3 Jan 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2062199686/9689. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uou67e00 (Accessed 21 May 2004)

- 48.[Philip Morris Companies Inc ]. Philip Morris' response to divestment proposals. Feb 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984814/4820. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lfd66c00 (Accessed 11 Dec 2002)

- 49.[Philip Morris] Divestment of Tobacco Company Stocks Is Not a Sound Financial Decision[California]. 11 Mar 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078174155/4161. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jyg72c00 (Accessed 31 May 2004)

- 50.Holsenbeck G P. N327[Recent contact with institutional shareholders]. 31 Oct 1995. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2048768693/8694. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xka57d00 (Accessed 8 Nov 2002)

- 51.Bring M H. [Letter to Alliance Capital Management's Vice Chair Alfred Harrison]. 11 Sep 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073730084/0085. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/szy85c00 (Accessed 14 May 2004)

- 52.Merksamer S. Facsimile Transmission. 28 Jan 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2063757470. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jky48d00 (Accessed 31 May 2004)

- 53.[Tobacco Institute] The Tobacco Institute 980000 Budget State Activities Division. 21 Aug 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2065493381/3425. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ufz63c00 (Accessed 23 Jul 2004)

- 54.Koppes R H. [Contact information on twelve public pension fund directors in seven states]. 10 Dec 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984794/4795. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hgr37c00 (Accessed 31 Oct 2003

- 55.Turner W G. Cal Tax Opposition to Ab 2717, as Amended 000324, Senate Revenue and Taxation Committee. 30 Mar 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2063758124. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nly48d00 (Accessed 31 May 2004)

- 56.[Philip Morris Companies Inc ]. Philip Morris' Response to Divestment Proposals. 28 Jun 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2062398513/8522. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lvf19e00 (Accessed 6 Jan 2004)

- 57.[Philip Morris] In Opposition to Divestment of Tobacco Company Stocks[Florida Final 4/18/97]. 18 Apr 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073464834/4840. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/knb37d00 (Accessed 21 May 2004)

- 58.[Philip Morris] N344[In Opposition To Divestment Of Tobacco Company Stocks—Massachusetts final]. 19 Jul 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070140992/0996. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dng47d00 (Accessed 20 May 2004)

- 59.[Smoking Control Advocacy Resource Center], [Philip Morris Management Corporation] In Favor of Divestment of Tobacco Holdings in Opposition to Divestment of Tobacco Company Stocks News Flash: Florida Pension Staff Urges Keeping of Tobacco Stock 961029. Nov 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421553/1560. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nuv37d00 (Accessed 18 May 2004)

- 60.Holsenbeck G P. The Case against Divestment of Tobacco Holdings by Fiduciary Investors[Published version]. Mar 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984740/4746. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rcp80c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 61.Dunham J. N804 [October Divestment Status Report]. 11 Nov 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2062404822/4826. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kqt47d00 (Accessed 10 May 2004)

- 62.[Ciazza AB] Carroll V, Clazza A B. Mayor's Stock Divestment Proposal Appears to Be Pure Political Pandering. 19 Nov 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2071770238. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zxh08d00 (Accessed 19 May 2004)

- 63.Algee D, Xx D, [Blount D] Smoking in Colorado Smoking Cough up to Cut Insurance Costs Some Investors Snuff Tobacco Stocks from Portfolios. 21 Nov 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2071770239/0240. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ayh08d00 (Accessed 19 May 2004)

- 64.[Hall LD] C M H, LD City Should Keep Money In Tobacco. 13 Dec 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421617. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ivv37d00 (Accessed 19 Nov 2004)

- 65.[Philip Morris] Government Affairs Weekly Report [970131]. 31 Jan 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074096783/6789. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zhc76c00 (Accessed 9 Jun 2004)

- 66.[Washington State Legislature] 980000 Washington State Legislative Report. 4 March 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2063744110/4115. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jem97d00 (Accessed 31 May 2004)

- 67.[Philip Morris] State Government Affairs ‐ Weekly Report [980123]. 23 Jan 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2064808300/8310. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mrl93c00 (Accessed 9 Jun 2004)

- 68.[Philip Morris] State Government Affairs Weekly Report [980403]. 3 Apr 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2065328787/8805. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bjp63c00 (Accessed 2 Jun 2004)

- 69.Greider W. The New Colossus. The Nation. 2005 28 Feb

- 70.California Public Employees' Retirement System Facts at a Glance: Investments. web site: California Public Employees' Retirement System; 2005 14 Mar 2005). http://www.calpers.ca.gov/eip‐docs/about/facts/investme.pdf (Accessed 22 Mar 2005)

- 71.California State Teachers' Retirement System Current Investment Portfolio. web site: California State Teachers' Retirement System, 2005 2005). http://www.calstrs.com/Investments/Invport.aspx (Accessed 22 Mar 2005)

- 72.[Philip Morris] Divestment tracking chart (900703). 3 Jul 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024258583/8585. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/efl98e00 (Accessed 1 Nov 2002)

- 73.Hanson D M. Divestiture from Tobacco Companies. 13 Feb 1991. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2041348170/8171. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ryf05e00 (Accessed 28 Jan 2004)

- 74.[Philip Morris] Divestment 920309. 9 Mar 1992. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2045749265/9270. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fcx45d00 (Accessed 6 Apr 2004)

- 75.Glantz S A, Balbach E D.Tobacco war: inside the California battles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000

- 76.D'Arelli M J. AB 3445 Analysis. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1996. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/95‐96/bill/asm/ab_3401‐3450/ab_3445_cfa_960430_164317_asm_comm.html (Accessed 6 Jul 2004)

- 77.Morain D. N100 [Bill to Divest State Tobacco Stocks Dies]. 15 Apr 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070090550/0551. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wsj47d00 (Accessed 14 May 2004)

- 78.[Philip Morris] Government Affairs Weekly Report [960426]. 26 Apr 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2065518969/8971. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wie73c00 (Accessed 9 Jun 2004)

- 79.Knox W. [Letter to CalPERS James Burton requesting attendance at legislative committee hearing]. Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449107. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tlo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 80.Knox W. [Letter to Geoffrey Bible requesting PM participation at a legislative committee hearing]. 3 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449108. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/slo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 81.Gillan K J. Fax Transmittal. 5 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449286. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jxo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 82.Aguallo R. Phone Memo. 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449282. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nxo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 83.Aguallo R. Facsimile Transmittal Cover Sheet. 5 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449283. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mxo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 84.Holsenbeck G P, Schulman R. [Faxcover to Michael Carpenter]. 5 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449285. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kxo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 85.Holsenbeck G P. [Draft of a letter to California Assemblyman Knox declining PM participation at his committee hearing]. 10 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077449105. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vlo67c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 86.Huntley J D, Vanhulzen C D. California Legislature Assembly Committee on Public Employees, Retirement and Social Security “Hearing on State Pension Fund Exposure to Risk Associated with Tobacco Investments, Particularly in Light of the Pending Settlement.” 19 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077459806/9815. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iqn62c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 87.Xx J. Hearing for the Assembly Committee on Public Employees, Retirement and Social Security. 19 Sep 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077459804. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kqn62c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 88.Legislative Counsel State of California AB 1679 Assembly Bill ‐ History. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1998. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97‐98/bill/asm/ab_1651‐1700/ab_1679_bill_19981130_history.html (Accessed 6 Jul 2004)

- 89.Legislative Counsel State of California AB 1744 Assembly Bill ‐ History. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1998. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97‐98/bill/asm/ab_1701‐1750/ab_1744_bill_19981130_history.html (Accessed 6 Jul 2004)

- 90.Legislative Counsel State of California SB 1433 Senate Bill ‐ History. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1998. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97‐98/bill/sen/sb_1401‐1450/sb_1433_bill_19981130_history.html (Accessed 6 Jul 2004)

- 91.Green K. AB 1744 Analysis [Assembly 4/1/98]. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1998. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97‐98/bill/asm/ab_1701‐1750/ab_1744_cfa_19980401_165041_asm_comm.html (Accessed 6 Jul 2004)

- 92.Dowd P M. DOWD RELATIONS. Ab 1744 (Knox) Position: Oppose Hearing: Assembly Pers Committee 980401. 26 Mar 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2063757595/7596. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tvl97d00 (Accessed 31 May 2004)

- 93.Holsenbeck G P. Calstrs ‐ Divestment. 18 Dec 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073952786. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hzs45c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 94.Gillan K J. California “RAID” History. web site: California Public Employees' Retirement System; 2004) http://www.calpers‐governance.org/viewpoint/speeches/gillan.asp (Accessed 31 Jan 2005)

- 95.[The Public Retirement Journal] Proposition 162 ‐ Five Years Later. Oct 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073952787/2791. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/izs45c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 96.Legislative Counsel State of California California Constitution Article 16 Public Finance. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1992. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/.const/.article_16 (Accessed 31 Jan 2005)

- 97.Green K. SB 1433 Analysis[Assembly 6/17/98]. website: Legislative Counsel State of California; 1998. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97‐98/bill/sen/sb_1401‐1450/sb_1433_cfa_19980415_081034_sen_comm.html (Accessed 6 Jul 2004)

- 98.Schnitt P. Calpers Inches Closer to Selling Tobacco Stock. 20 Jun 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2083542679/2680. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vbz35c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 99.Palmeri C. Calpers May Not Do as Well by Doing Good. 19 Jun 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2081590454. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ixq65c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 100.Council For Responsible Public Investment Public funds with restrictions on tobacco investments. Oakland, CA Council For Responsible Public Investment 2000

- 101.[Schwartz R ] Phone Call [from the Office of the California Treasurer]. 16 Feb 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984821. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mfd66c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 102.Holsenbeck G P. [Faxcover to California Treasurer's Office]. 16 Feb 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984822. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lcp80c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 103.Holsenbeck P. Calstrs. 6 Apr 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078168141. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tle72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 104.Laufer D. Fw: Calstrs. 6 Apr 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078168140. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ule72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 105.Holsenbeck P Re: Calstrs. 6 Apr 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078168139. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vle72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 106.Laufer D. Fw: Calstrs. 6 Apr 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078168138. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wle72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 107.Carpenter M. Re: Calstrs. 11 Apr 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078168137. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xle72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 108.Dunham J. California Divestment. 8 Jun 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078168083. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pne72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 109.California Public Employees' Retirement System CalPERS Votes To Sell Tobacco Stocks. web site: California Public Employees' Retirement System, 2000 25 Mar 2004. http://www.calpers.ca.gov/index.jsp?bc = /about/press/archived/pr‐2000/oct/tobacco.xml (Accessed 22 Mar 2005)

- 110.Welle J R, Ibrahim J K, Glantz S.Tobacco control policy making in North Dakota: a tradition in activism. San Francisco: University of California San Francisco, 2004

- 111.Cramer M T, Nelson J R. Ads. 10 Oct 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073528239. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lzb37d00 (Accessed 16 Sep 2004)

- 112.[Anhauser‐Busch] Are You Drinking North Dakota Barley? Oct 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2073528240/8241. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mzb37d00 (Accessed 16 Sep 2004)

- 113.Crawford D L. Divestment Overview ‐ 920000. 24 Feb 1992. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2023919104/9112. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bpx45d00 (Accessed 6 Apr 2004)

- 114.[Philip Morris Companies Inc.] State Overview: North Dakota. 1 Sep 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No.2063393122. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kyg53a00 (Accessed 20 Sep 2004)

- 115.North Dakota Legislative Council Uniform Prudent Investor Act. web site: State of North Dakota; 1997. http://www.state.nd.us/lr/assembly/55‐1997/ranch/SL7TRSTS.pdf (Accessed 26 Jan 2005)

- 116.Legislative Counsel State of North Dakota Measure Actions HB 1092 Versions. web site: State of North Dakota; 1997. http://www.state.nd.us/lr/assembly/55‐1997/bill‐actions/BA1092.html (Accessed 1 Feb 2005)

- 117.[Philip Morris] Divestment tracking chart (900816). 16 Aug 1990. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2024672811/2813. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uns24e00 (Accessed 6 Nov 2002)

- 118.Stern D. Wilshire 5000 excluding tobacco stocks. 23 Aug 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984698/4699. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lqd66c00 (Accessed 21 Oct 2003

- 119.[Advocacy Institute] ADVOCACY INST, SCARCNET DAILY BULLETIN, SMOKING CONTROL ADVOCACY RESOURCE CENTER. Lott, Gingrich Comment on Settlement Talks California Bill Will Free State to Sue Tobacco Industry Class Action Status Denied to Castano Spin Off Suit in Pennsylvania Wa State Pension Committee Urges Tobacco Stock Divestment New Hampshire Files Medicaid Suit. 5 Jun 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078824390A/4392. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ucx67c00 (Accessed 28 May 2004)

- 120.Burton K, Prager G. Quitting Profitable Tobacco Stocks Is Hard for Pension Funds. 10 Jun 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421622. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lvv37d00 (Accessed 28 May 2004)

- 121.Pemberton‐Butler L, Prager G. State Will Stick with Tobacco Stock, Rejecting Divestment as ‘Political'. 17 Jun 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421623. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mvv37d00 (Accessed 28 May 2004)

- 122.[Philip Morris] Divestment Activity Report: 970829. 29 Aug 1997/E. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984808/4810. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jfd66c00 (Accessed 28 Oct 2002)

- 123.Limbacher P B. Tobacco Bans Miss Plans Despite Pressure, State Funds Hanging Tight With Stock. 14 Nov 1994. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421520/1522. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/buv37d00 (Accessed 28 Apr 2004)

- 124.Diebert D. Conversation with Washington State Code Advisor concerning history of divestment in state legislature. Personal communication to N. Wander. San Francisco. 17September2003

- 125.Sandison T. Testimony Of Trevor Sandison Representing Philip Morris Before The Washington Senate Financial Institutions And Housing Committee. 1995 (est.). Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078840964/0967. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ybe36c00 (Accessed 30 Apr 2004)

- 126.[Philip Morris] In Opposition to Divestment of Tobacco Company Stocks[Washington Draft 2]. 6 Jun 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078302253/2258. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xyo75c00 (Accessed 27 May 2004)

- 127.Legislature W S. Certification of Enrollment Senate Bill 6192 Chapter 14, Laws of 1998. web site: Washington State Legislature; 1998. http://www.leg.wa.gov/pub/billinfo/1997‐98/senate/6175‐6199/6192_sl_031298.txt (Accessed 22 Mar 2005)

- 128.Legislature W S. SB 6192 Digest. web site: Washington State Legislature; 1998. http://www.leg.wa.gov/pub/billinfo/1997‐98/senate/6175‐6199/6192_dig_033198.txt (Accessed 22 Mar 2005)

- 129.Moore C. Conversation with National Council on Teacher Retirement National Counsel. Personal communication to Wander N. San Francisco. 10June2004

- 130.Legislature W S. House Bill Report SB 6192. web site: Washington State Legislature; 1998. http://www.leg.wa.gov/pub/billinfo/1997‐98/senate/6175‐6199/6192_011398.txt (Accessed 22 Mar 2005)

- 131.Legislative Counsel State of North Dakota Legislative Council Report: Judiciary. Bismark State of North Dakota 1997

- 132.Wellman R V, Gravel C A, Langbein J H, Stein R A. Uniform Prudent Investor Act: National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws; 1994. http://www.state.nd.us/lr/assembly/55‐1997/bill‐actions/BA1092.html (Accessed 2 Feb 2005)

- 133.Langbein J H, Schotland R A, Blaustein A P.Disinvestment. Is it legal? Is it moral? Is it productive?: an analysis of politicizing investment decision. Washington, DC: National Legal Center for the Public Interest, 1985

- 134.Langbein J H. [Cover letter to revised Philip Morris' Response to Divestment Proposals]. 30 May 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2077235270. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uck62c00 (Accessed 6 Jan 2004)

- 135.Legislature W S. An act relating to prohibiting investment of public pension and retirement funds in business firms manufacturing tobacco products: State of Washington; 2000. http://www.leg.wa.gov/pub/billinfo/1999‐00/house/2725‐2749/2743.pdf (Accessed 28 Jan 2005)

- 136.Vargas C. Wa ‐ Divestment. 20 Jan 2000. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078170848. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xuf72c00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 137.Legislature W S. History of HB 2743. web site: State of Washington; 2000. http://www.leg.wa.gov/pub/billinfo/1999‐00/house/2725‐2749/2743_history.txt (Accessed 28 Jan 2005)

- 138.Legislature W S. Bill Information. web site: State of Washington, 2005) http://www.leg.wa.gov/wsladm/billinfo1/bills.cfm (Accessed 28 January 2005)

- 139.Sims J. Investment Officer, Denver Employees Retirement Plan. Personal communication to Wander N. San Francisco. 25 Jan

- 140.[Philip Morris] Government Affairs Weekly Report [970627]. 27 Jun 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2078294341/4344. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/odq75c00 (Accessed 9 Jun 2004)

- 141.[Philip Morris] State Government Affairs Weekly Report [981002]. 2 Oct 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074331414/1418. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wsh52c00 (Accessed 2 Jun 2004)

- 142.National Center For Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Best Practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs, August 1999: executive summary: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/research_data/stat_nat_data/bestprac‐execsummay.htm (Accessed 28 Mar 2005)

- 143.Fennel M, Krevor B, Macleod B, Malone J, Meehan M, [NECN‐TV] Transcript. 2 Oct 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2075984116. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hnd55c00 (Accessed 25 May 2004)

- 144.[Unknown] Legislature Wants Pension Fund to Drop Tobacco Investments Bill Nears Passage. 22 Aug 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2075984120. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lnd55c00 (Accessed 28 May 2004)

- 145.[WTVJ‐TV] VIDEO MONITORING SERVICES OF AMERICA. N100[Channel 6 News Midday]. 15 Jan 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070090513/0514. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jsj47d00 (Accessed 26 May 2004)

- 146.[Philip Morris] Government Affairs Weekly Report 970529. 29 May 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2062500069/0070. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/amb42e00 (Accessed 9 Jun 2004)

- 147.[Philip Morris] State Government Affairs Weekly Report 990324. 24 Mar 1999. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2063756393/6400. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dvl97d00 (Accessed 3 Jun 2004)

- 148.[Philip Morris] N832 [In Opposition to Divestment of Tobacco Company Stocks—Arizona]. 11 Jun 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2061897339/7343. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lax47d00 (Accessed 12 May 2004)

- 149.Obermayer J, Sarris M. State, City Pension Funds Invest Millions In Tobacco Companies. 1 Aug 1994. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421523/1526. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cuv37d00 (Accessed 28 Apr 2004)

- 150.Spangler T. Should State Invest In Tobacco Firms? 10 Apr 1995. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421518/1519. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/auv37d00 (Accessed 3 May 2004)

- 151.Associated Press N100 [Maryland state fund drops tobacco stocks prior to suit]. 02 May 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070090639. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/juj47d00 (Accessed 3 May 2004)

- 152.[Unknown] Vermont Divestiture. 13 May 1997. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074984735. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yed66c00 (Accessed 24 May 2004)

- 153.Baden P L. State Board Rejects Plan to Stop Investing in Tobacco Companies. 5 Sep 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421606/1608. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dvv37d00 (Accessed 14 May 2004)

- 154.[Philip Morris] State Government Affairs Weekly Report[980904]. 4 Sep 1998. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2074331438/1441. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qsh52c00 (Accessed 2 Jun 2004)

- 155.Precious T. Limits Urged On Cigarette Company Stock. 20 Mar 1996. Philip Morris. Bates No. 2070421509/1510. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xtv37d00 (Accessed 3 May 2004)

- 156.Offen N, Smith E A, Malone R E. The perimetric boycott: a tool for tobacco control advocacy. Tob Control 200514272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Thomson G, Wilson N. Directly eroding tobacco industry power as a tobacco control strategy: lessons for New Zealand. N Z Med J 2005118(1223)U1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]