Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the effects of television (TV) viewing on children’s lunch and snack intake in one condition when the children watched a 22-minute cartoon video on TV (TV group), and in another without the TV (no TV group). Participants included 24 children and their parents, recruited from a university child-care center. Parents reported children’s TV viewing habits at home. Overall, children ate significantly less snack and lunch in the TV condition compared with the no TV condition. However, children who reportedly watched more daily hours of TV and who had a higher frequency of meals eaten in front of the TV at home ate more lunch in the TV condition. TV viewing may either increase or reduce children’s intake, depending on prior experience with eating during TV viewing.

Children in the United States spend almost 20 hours per week watching television (TV) (1). Recent studies show that a large proportion of young children’s meals are consumed during TV viewing (2,3), but little is known about the impact of TV viewing on concomitant food intake in children. Experimental studies in adults suggest that allocation of attention on tasks such as video games or TV while eating may disrupt the ability to regulate energy intake and promote overeating (4-8). The objective of this study was to examine the effects of TV viewing on preschool children’s concomitant food intake, and to examine whether age, sex, weight status, or TV viewing history moderated the effects of TV viewing on food intake.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 3- to 5-year-old (mean, 4.6±0.7 years) preschool children attending a full-day university day-care program in central Pennsylvania. Of the 40 age-eligible children in two classrooms, 24 children (12 male, 12 female) were given consent to participate in the study; complete data were obtained from 17 mothers. The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and mothers provided consent for their family’s participation before the study began.

Study Design and Procedures

A within-subjects 2×2 factorial design was used to examine children’s lunch and snack intake in two conditions, with and without TV viewing. Children within classrooms were randomized into one of three experimental orders in which they were exposed to each TV condition (TV/no TV) on five occasions: once during an initial session intended to familiarize them with the procedures and setting, and four times during the experimental period. Children visited the laboratory 2 days per week for 6 weeks, during their regularly scheduled lunch and afternoon snack periods, in groups of four to eight children. Children sat in assigned seats at each session and were always seated with the children they normally ate lunch with in their classroom. A teacher or student helper was always present but not eating with children at each session. For all sessions, children were given 22 minutes to complete their meal and were given a reminder when 5 minutes were remaining. A 22-minute video, Daisy-Head Mayzie (Hanna-Barbera Cartoons, Inc, Warner Bros. Entertainment, a Time Warner Company) was used in the TV condition. The story concludes with a lesson that love is more important than fame; there are no food messages in this video. Children watched the same video during each meal in the TV condition.

Experimental Menu

For lunch sessions, children were served pizza, unsweetened applesauce, baby carrots, and 2% milk. Children were given three slices of pizza (225 g, 480 kcal) so that intake was unlikely to be limited by food availability. Single servings were provided for all other lunch foods: applesauce (113 g, 50 kcal), carrots (30 g, approximately 11 kcal), and milk (297 ml, 140 kcal). For snack, children were served 2% milk and two snack food options: fish-shaped baked snack crackers and dried sweetened banana chips. Two servings of the snack crackers (60 g, 300 kcal) and approximately three servings of the banana chips (85 g, 441 kcal) were served.

Measures

Foods were weighed before and after each session to calculate gram intakes, and any spilled foods were collected and added to the weight of that food after the intervention. The manufacturer’s information for each food was used to calculate energy intakes for lunch and snack sessions. All eating sessions were video recorded. Observers coded videotapes to measure children’s attention allocation during the TV condition and to note whether there were any problems that may have affected children’s food intake during the experimental session (eg, misbehavior). Observers made behavioral observations separately for each child and noted whether or not the child was looking at the TV at 30-second intervals; 30-second-interval prompts were prerecorded, and observers listened to the recording through headphones.

Children’s height and weight measurements were measured by trained research assistants following procedures described by Lohman and colleagues (9), and were used to calculate body mass index (BMI; calculated as kg/m2). The BMI values were converted to age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts (10); children were classified as at risk for overweight if the BMI percentile was ≥85 and overweight if the BMI percentile was ≥95.

Parents reported the average number of daily hours children watched TV on school and nonschool days using questions developed in our laboratory. To measure children’s eating while watching TV, parents responded to three questions that asked how frequently the child eats a snack while watching TV, how frequently the child eats other meals while watching TV, and how frequently the TV is on when meals are eaten together as a family. Response options ranged from 1 to 4, where 1=rarely/never and 4=regularly.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using the SAS version 8.2 software package (2001, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Intakes for each meal were averaged across measurement occasions (ie, average of two snack meals, average of two lunch meals) for each of the four conditions. Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables of interest; paired t tests were used to examine differences in energy intake during eating sessions (lunch/snack) across the two experimental conditions (TV/no TV). Analysis of variance was used to examine the effects of age group, sex, and weight status on children’s intakes across experimental conditions. Previous laboratory-based studies of food intake in preschool children showed significant differences in intake between children above and below age 4 years (11,12); thus, for the present study, children <4 years old were defined as younger, and children ≥4 years old were defined as older. Spearman correlations were used to examine relationships between children’s intakes in the experimental sessions and parental reports of children’s TV viewing behaviors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Children were within the normal range for BMI (15.9±1.2), corresponding to a BMI percentile of 61. Mothers were, on average, in their mid-30s (35.4±6.0 years), predominantly non-Hispanic white, and well educated, with 84% reporting some college education. A majority of families (76%) reported mean annual family incomes >$50,000. Mothers reported that children watched an average of 1.5 hours of TV daily, and that 33% of children reportedly ate meals or snacks while watching TV; reports ranged from occasionally to relatively often.

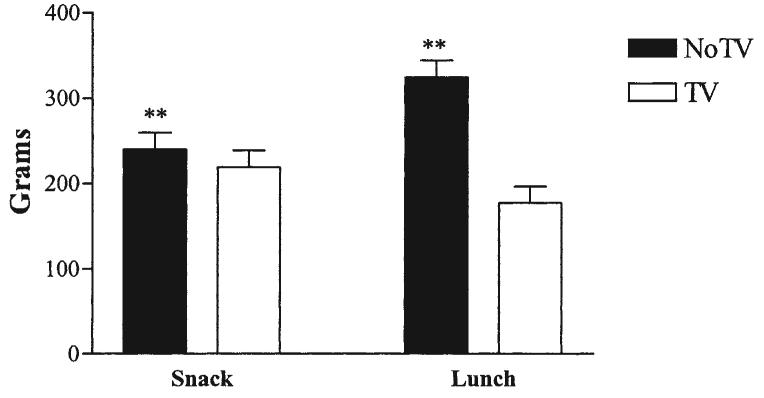

The results on children’s attention allocation during meals showed that children were fixated with the TV 93% of the time during lunch meals, and 96% of the time during snacks; thus, children were actively engaged with the TV program. As shown in Figure 1, intake was significantly higher in the no TV condition than in the TV condition for both snack [t(24)=3.1, P<0.01] and lunch [t(24)=4.2, P<0.001] meals. A main effect of age group was evident for intake during meals; older children (≥4 years) ate significantly more than younger children (<4 years) in all but the lunch with no TV condition (Figure 2). There were no significant effects of sex or weight status on children’s intakes across meals or conditions.

Figure 1.

Intake differences between meals and experimental conditions for children eating lunch with and without television (TV) viewing. **Indicates intake was significantly higher in the no television conditions for both snack and lunch meals at P<0.01.

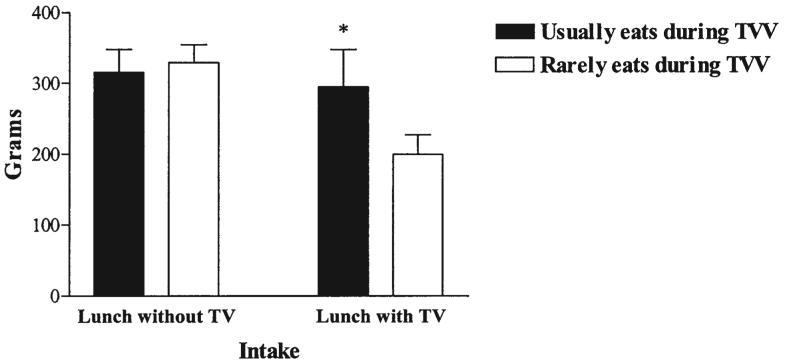

Figure 2.

Differences in lunch intakes with and without television (TV) based on children’s histories of eating during TV viewing (TVV) at home. Children who reportedly eat while watching TV at home (n=8) had higher lunch intakes in the TV condition compared with children who rarely or never eat while watching TV at home (n=16). *Indicates a significant difference at P≤0.05.

With respect to children’s TV viewing patterns at home, results showed that children who reportedly watched more daily hours of TV ate more lunch in the TV condition (r=0.56, P<0.05). In addition, parental reports of the frequency of children’s eating during TV viewing at home were linked to higher energy intake at lunch in the TV condition (r=0.52, P<0.05). Thus, eating in front of the TV promoted higher energy intakes at lunch among children who had more experience eating while watching TV (Figure 2).

The results of this study show that TV viewing can either increase or decrease preschool children’s food intakes. Children in this study ate significantly less at snack and at lunch meals while watching TV compared with meals without the presence of TV. However, children’s home TV viewing patterns, including daily TV viewing and eating while watching TV, were linked to higher energy intakes at lunch during TV viewing in the experimental setting. This finding suggests the possibility that children who are given opportunities to eat while watching TV may become less sensitive to internal cues to satiety. Additional research is needed to explore this possibility. Although results from recent studies show that eating while watching TV is linked to increased weight status in children (13-15), we did not find significant links with weight status in this study. Although we are limited by our small sample, the results of this study suggest that among this group of preschool-aged children, TV viewing reduced energy intake during meals and snacks for some children. For other children, particularly children who are accustomed to eating during TV viewing, TV viewing increased intake compared with the situation in which eating occurred in the absence of TV viewing.

CONCLUSIONS

To promote self-regulation of energy intake in young children, parents and caregivers should be advised against providing opportunities for children to eat during TV viewing.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HD32973 and HD3297303S1, and a small grant from The Pennsylvania State University Alumni Society Board of the College of Health and Human Development.

The authors thank all of the families who participated in this research study, The Pennsylvania State Child Development Laboratory for their cooperation, and the students and staff who assisted with data collection.

References

- 1.Nielsen Media Research . 2000 Report on Television. 2000. pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matheson DM, Wang Y, Klesges LM, Beech BM, Kraemer HC, Robinson TN. African-American girls’ dietary intake while watching television. Obes Res. 2004;12(suppl 1):S32–S37. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matheson DM, Killen JD, Wang Y, Varady A, Robinson TN. Children’s food consumption during television viewing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellisle F, Dalix AM, Slama G. Non food-related environmental stimuli induce increased meal intake in healthy women: Comparison of television viewing versus listening to a recorded story in laboratory settings. Appetite. 2004;43:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein LH, Rodefer JS, Wisniewski L, Caggiula AR. Habituation and dishabituation of human salivary response. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90075-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein LH, Mitchell SL, Caggiula AR. The effect of subjective and physiological arousal on dishabituation of salivation. Physiol Behav. 1993;53:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90158-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein LH, Saad FG, Handley EA, Roemmich JN, Hawk LW, McSweeney FK. Habituation of salivation and motivated responding for food in children. Appetite. 2003;41:283–289. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroebele N, de Castro JM. Television viewing is associated with an increase in meal frequency in humans. Appetite. 2004;42:111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R, editors. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Human Kinetics Books; Champaign, IL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM. Criteria for definition of overweight in transition: Background and recommendations for the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1074–1081. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rolls BJ, Engell D, Birch LL. Serving portion size influences 5-year-old but not 3-year-old children’s food intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:232–234. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher JO, Rolls BJ, Birch LL. Children’s bite size and intake of an entree are greater with large portions than with age-appropriate or self-selected portions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1164–1170. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Utter J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Jeffery R, Story M. Couch potatoes or french fries: Are sedentary behaviors associated with body mass index, physical activity, and dietary behaviors among adolescents? J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1298–1305. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)01079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips SM, Bandini LG, Naumova EN, Cyr H, Colclough S, Dietz WH, Must A. Energy-dense snack food intake in adolescence: Longitudinal relationship to weight and fatness. Obes Res. 2004;12:461–472. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis LA, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental weight status and girls’ television viewing, snacking, and body mass indexes. Obes Res. 2003;11:143–151. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]