Abstract

Background

Preferences for life-sustaining treatment elicited in one state of health may not reflect preferences in another state of health.

Objective

We estimated the stability of preferences for end-of-life treatment over 3 years and whether decline in physical functioning and mental health were associated with change in preferences for end-of-life treatment.

Design

Mailed survey of older physicians.

Setting

Longitudinal cohort study of medical students in the graduating classes from 1948 to 1964 at Johns Hopkins University.

Participants

818 physicians who completed the life-sustaining treatment questionnaire in 1999 and 2002 (mean age 69 years at baseline).

Measurements

Preferences for life-sustaining treatment, assessed using a checklist questionnaire in response to a standard vignette.

Results

While the prevalence of the three clusters of life sustaining treatment preferences remained stable over the 3-year follow-up interval, certain physicians changed their preferences over time. The probability that physicians were in the same cluster at follow-up as at baseline was 0.41 for “most aggressive,” 0.50 for “intermediate care,” and 0.80 for “least aggressive.” Physicians without an advance directive were more likely to transition to the “most aggressive” than to the “least aggressive” cluster over the course of the 3-year follow-up (odds ratio 1.96, 95% confidence interval [1.11, 3.45]). Age at baseline and decline in physical and mental health were not associated with transitions between 1999 and 2002.

Limitations

The preferences we elicited might not accurately predict treatment decisions during actual illness.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that periodic re-assessment of preferences are most critical for patients who desire aggressive end of life care or do not have advance directives. (261 words)

BACKGROUND

Crossing the Quality Chasm called for a vision of the health system that is more responsive to the wishes and preferences of patients (1). Nowhere is the quality of care more dependent on eliciting patient and family wishes and values than in the arena of end-of-life care. Goals of quality of end-of-life care outlined by Singer and colleagues depend on eliciting the preferences of patients and families: receiving adequate pain and symptom management, avoiding inappropriate prolongation of dying, achieving a sense of control, relieving the burden on loved ones, and strengthening relationships with loved ones (2). Nevertheless, studies reveal that 4 in 10 dying patients had severe pain most of the time (3), almost half of incurably ill patients with advanced dementia and metastatic cancer received non-palliative treatment (4), and bereaved family members felt that communication concerning end-of-life care issues was poor (5). Efforts to improve the experience of patients and families at the end of life must incorporate patient perspectives. Advance directives are one strategy through which patient preferences can be elicited and recorded to be invoked at a time when the patient may not be able to make decisions directing care. Since the advent of the Patient Self Determination Act, hospitals, nursing homes, and health care programs have been required to ask patients about advance directives and then incorporate the information into medical records. Clinicians are being encouraged to work with patients and families to fill out advance directives in the out-patient setting. Despite the emphasis on eliciting and documenting preferences for good quality of end-of-life care, factors related to clinical aspects of eliciting end-of-life preferences, such as stability of choices, have not been extensively studied among community-dwelling older adults.

We estimated the stability of preferences for end-of-life treatment over 3 years and whether decline in physical functioning and mental health were associated with change in preferences for end-of-life treatment among participants in one of the oldest aging studies in the world, the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Given the age and functional status of the physician respondents, end-of-life considerations are a reality, not just hypothetical Based on previous work (6, 7), we hypothesized that transitions to more aggressive categories of treatment preference might be more likely among respondents without an advance directive or with declining self-rated physical function and mental health.

METHODS

The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study

The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study was designed in 1946 by Caroline Bedell Thomas to identify characteristics associated with premature cardiovascular disease and death (8–11). All 1,337 students who matriculated into the graduating classes of 1948 to 1964 of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine were eligible. Precursors Study procedures have been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Assessment of preferences for potentially life-sustaining treatment

The 1999 and 2002 questionnaires included items about whether the participating physician had or was considering obtaining a living will or durable power of attorney for health care. Participants were also asked to consider what types of treatment they would want if they suffered irreversible brain damage that left them unable to speak understandably or to recognize people (6, 7). In the scenario, based on the Medical Directive developed by Emanuel and Emanuel (12), the participants were told that they had no terminal illness and might remain in this brain-injured state for a long period of time. We selected the scenario of irreversible brain damage without terminal illness because previous research demonstrated that this scenario provided a greater degree of variability of responses than other vignettes in the Medical Directive (12, 13). The participants were asked to state their wishes regarding the use of ten medical interventions: CPR, mechanical ventilation, intravenous fluids, surgically placed feeding tube for nutrition, dialysis, chemotherapy, major surgery, invasive diagnostic tests, blood or blood products, and antibiotics (6). The responses for each intervention were coded a priori into a dichotomous variable as either reject (“No, I would not want”) or accept (yes, undecided, or trial of treatment). This dichotomization has been used by other investigators and reflects common clinical practice in which “treatment trial” and “unsure” would translate into providing life-sustaining treatment to incompetent patients, at least initially (7, 13, 14).

Assessment of physical functioning and mental health

The SF-36 was administered to the Precursors Study cohort as part of the annual questionnaires in 1999 and 2002 and was scored using standard techniques (15). The SF-36 has been employed in studies of patient care outcomes (16–20), and is reliable and valid in older adults (21–23). The mental health subscale, known as the 5-item version of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI), has been found to be an accurate screening instrument for the detection of major depression and other affective disorders (24). Because there are no standardized thresholds for dichotomized change scores on the SF-36 subscales, thresholds for significant changes in physical functioning and depression were established a priori based on clinically significant thresholds reported in a psychometric analysis of the SF-36 (25). The physical functioning change score was dichotomized at 20 (i.e., a decline of 20 or more points on the physical functioning subscale between the 1992 and 1998 questionnaires represented a clinically meaningful decline in physical functioning) and the depression change score at 5.

Analytic strategy

In order to study potentially life-sustaining treatments as a pattern or set of treatments (“latent classes”) in contrast to a focus on individual interventions, we applied the latent transition model (26–28). The model provides for simultaneous estimation of: (1) clusters of end of life treatment preferences; (2) transition probabilities from one cluster of preferences to another; and, (3) predictors of transitions from one cluster to another. We discuss the details of the latent transition model in an Appendix.

Data analysis was performed using Mplus version 4.1 and WinLTA version 3.1 which both utilize an efficient estimation-maximization (EM) algorithm for maximum likelihood estimation (29). Model choice, in terms of the number of latent classes, was determined through examination of fit indices as well as in relation to clinically interpretable results. Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) (30) were used to compare non-nested models that differed in the number of latent classes. A smaller value of BIC indicates a better model fit. A Goodness of Fit statistic, G2, was used to assess the model goodness of fit for nested models with the same number of latent classes but which differed in the number of parameters estimated (31). The three-class model yielded the best fit at both time points over two- or four-class models using statistical criteria (BIC3=9262.64, BIC4=9477.47, BIC2=10046.22).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The effective sample size for this analysis was 818 physicians Of the 1,016 participants to whom questionnaires were sent in 1999, 773 responded with expression of preferences for the brain injury scenario (76% participation). In 2002, 970 participants were sent questionnaires and 721 returned with information on end-of-life preferences (74% participation rate). Persons who only had preference data at one time point contributed to estimates of preference class and not to the transition probability. The mean age ± standard deviation of the study sample at baseline was 69 ± 5.4 years. Reflecting medical school enrollment between 1948 and 1964, the study sample was 92% white men. The mean physical functioning score ± standard deviation as assessed by the SF-36 was 86.1 ± 20.3 in 1999 and 83.5 ± 20.9 in 2002. The mean mental functioning score ± standard deviation as assessed by the SF-36 was 85.0 ± 11.8 in 1999 and 86.2 ± 10.4 in 2002.

Change in specific intervention preferences between 1999 and 2002

Table 1 shows preferences for life-sustaining treatments in response to the hypothetical scenario in 2002 by preferences assessed in 1999. In general, procedures that were declined in 1999 were likely also to be declined in 2002. Nevertheless, a substantial proportion of persons who desired an intervention in 1999 declined the treatment in 2002.

Table 1.

Preferences for specific potentially life-sustaining treatments (in response to the hypothetical brain death scenario) in 1999 compared to preferences in 2002. Data from the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study (1999–2002). Numbers in parentheses are row percents, stratified by whether the interventions were desired in 1999.

| Desired intervention in 1999? | yes | yes | no | no |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desired intervention in 2002? | yes | no | yes | no |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | ||||

| 27 (42) | 37 (58) | 48 (8) | 536 (92) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| 33 (37) | 56 (63) | 55 (10) | 514 (90) | |

| Intravenous fluids | ||||

| 176 (65) | 95 (35) | 87 (23) | 296 (77) | |

| Feeding tube | ||||

| 84 (55) | 68 (45) | 65 (13) | 440 (87) | |

| Major surgery | ||||

| 56 (44) | 70 (56) | 87 (17) | 426 (83) | |

| Dialysis | ||||

| 41 (46) | 48 (54) | 62 (11) | 509 (89) | |

| Chemotherapy for cancer | ||||

| 45 (44) | 58 (56) | 66 (12) | 489 (88) | |

| Invasive diagnostic testing | ||||

| 78 (59) | 55 (41) | 84 (17) | 422 (83) | |

| Blood or blood products | ||||

| 106 (62) | 65 (38) | 90 (18) | 398 (82) | |

| Antibiotics | ||||

| 177 (69) | 78 (31) | 99 (25) | 302 (75) | |

Treatment preference categories in 1999 and 2002

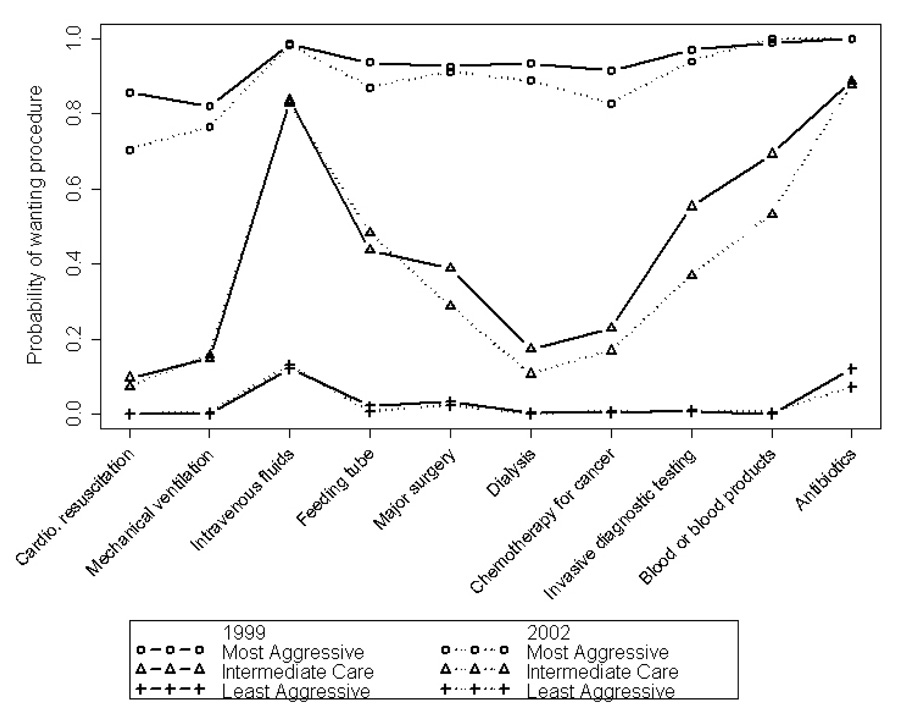

Preferences derived from the latent transition model grouped together the same way in 1999 and in 2002; namely, (1) a cluster representing desiring most interventions (“most aggressive” category); (2) a cluster declining most interventions (“least aggressive” category); and (3) an intermediate cluster (which we have labeled “intermediate care”) in which the primary interventions desired were only intravenous fluids and antibiotics. Figure 1 shows the probability of desiring specific interventions given treatment preferences in 1999 and in 2002. The vertical axis in Figure 1 shows the probability of desiring specific interventions among persons in a given category of treatment preferences (“most,” “least,” or “intermediate” categories).

Figure.

Probability of desiring specific interventions given category of desire for aggressiveness of care in 1999 (solid lines) and 2002 (dotted lines). Data from the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study (1999–2002).

Transitions between 1999 and 2002

Although preferences for end-of-life care clustered together in the same way in 1999 and 2002 (Figure), respondents moved from one cluster to another over the course of the 3-year follow-up (Table 2). For example, among persons in the most aggressive category of preferences, the probability of remaining in the most aggressive category 3 years later was 0.41 (upper left corner of Table 2).

Table 2.

Probability of being in a specific category in 2002 given treatment preferences in 1999. Estimated prevalence of each category in 1999 and 2002 are shown in parentheses. Data from the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study (1999–2002).

| Category of potentially-life sustaining treatment preferences in 2002 (prevalence) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most aggressive (14%) | Intermediate care (26%) | Least aggressive (60%) | ||

| Most aggressive (12%) | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.26 | |

| Intermediate care (26%) | 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.30 | |

| Least aggressive (62%) | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.80 | |

Covariates and transitions between 1999 and 2002

The association of covariates with change in preference between 1999 and 2002, as measured by the odds ratio, is shown in Table 3. Age and decline in mental or physical health (as measured by the SF-36) were not statistically significantly associated with transitions to the most aggressive category compared to transitions to the least aggressive category (the associated confidence intervals included the null). However, physicians who reported having no living will or durable power of attorney were twice as likely to make a transition to the most aggressive category as to the least aggressive category of potentially life-sustaining treatments (odds ratio 1.96, 95% confidence interval [1.11, 3.45]). Table 3 shows there were no statistically significant associations of specific covariates with transition to the intermediate care category compared with transitions to the least aggressive category.

Table 3.

Association of covariates with transitions to the most aggressive category compared to the least aggressive category (left most column) and transitions to intermediate care compared to the least aggressive category (right most column). Table entries are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals in brackets. Data from the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study (1999–2002).

| Transition to mostaggressive categorycompared to transitionto least aggressive category | Transition tointermediate carecategory compared totransition to leastaggressive category | |

|---|---|---|

| Age 70 years and older in 1999(reference: Less than 70 years old) | 0.93[0.53, 1.61] | 1.05[0.66, 1.68] |

| Decline in mental health from 1999 to2002 of 5 points or more (reference:Less than 5 point decline) | 0.88[0.46, 1.69] | 0.68[0.37, 1.24] |

| Decline in physical health from 1999 to2002 of 20 points or more (reference:Less than 20 point decline) | 0.95[0.38, 2.37] | 0.86[0.40, 1.83] |

| No living will or durable power ofattorney for health care (reference:Reports having a living will or durablepower of attorney for health care) | 1.96[1.11, 3.45] | 0.98[0.58, 1.67] |

DISCUSSION

The latent transition analysis allowed us to classify preferences for end-of-life treatment into three clinically-relevant clusters based on responses of physicians to a standard assessment instrument asking about 10 potentially life-sustaining interventions. While the preferences as tapped by the instrument appeared to cluster the same way in 1999 and 2002 (‘most aggressive,” “least aggressive,” and “intermediate care”), the likelihood that physicians changed their preferences for end-of-life care was related to their cluster at baseline. Most physicians in our sample fit into the least aggressive treatment preference category, and the physicians who chose “least aggressive” treatments at baseline were the least likely to change preferences over time (80% of persons in the “least aggressive” category at baseline were in the same category at follow-up). Physicians in the “most aggressive” category of preferences at baseline were the most likely to change preferences over time (41% of the persons in the “most aggressive” category at baseline were in the same category at follow-up). In addition, we found that physicians without an advance directive were twice as likely as those with advance directives to transition to the “most aggressive” category compared to a transition to the “least aggressive” category over the course of a 3-year follow-up. Age and decline in physical or mental health as measured by a standard instrument were not associated with transitions in preference categories.

Before discussing the implications of our findings, it is important to consider the potential limitations of our study. First, our study sample was a cohort of older physicians who graduated from one medical school and have participated in a longitudinal study. The generalizability of the results may be limited to physicians. However, since older physicians are highly likely to have had professional experience with both the life-sustaining treatments and the complications of severe irreversible brain damage as presented in our questionnaire, our results are unlikely to be influenced by participant misunderstanding of the conditions and interventions asked about in the questionnaire. Also, we would argue that because the respondents are physicians, and previous studies suggest that experience with specific treatments may be associated with stability in preferences for health care (32), our estimates of change are likely to be conservative. In other words, we would expect this sample to provide an estimate of changeability that would be more stable than samples of persons with less medical education or experience. However, we acknowledge the possibility that physicians may have either been influenced by answering the study questions or may have seen patient cases that changed their minds about their preferences. Second, the measures of physical and mental health were based on subjective assessment by the respondents and not on objective evaluation. Yet, the participants were physicians who have been shown to provide accurate reports of their health (8). Third, we classified the respondents using a statistical model to characterize preferences. We believe our categorization was more clinically relevant than methods that either evaluated the difference in the number of interventions accepted (33–36) or assessed only acceptance or rejection of CPR (37–40). Fourth, we dichotomized the responses to the scenario so that those who were “unsure” or wanted “a treatment trial” were counted as desiring that treatment. While this reflects common clinical practice in which “treatment trial” and “unsure” would translate into providing life-sustaining treatment to incompetent patients, we realize this limits our ability to study transitions involving those responses. Fifth, by eliciting treatment preferences using a hypothetical illness scenario, the preferences we elicited might not accurately predict treatment decisions during actual illness. On the other hand, as hypothetical scenarios are frequently used in advance directive documents, our methodology reflects common medical practice regarding planning for end-of-life care. Finally, though our findings suggest that physicians without an advance directive had less stable preferences over time than those with an advance directive, we cannot rule out the possibility that persons who choose to have advance directives strongly desire less treatment at the end of life.

Prospective studies that have examined factors associated with change in preferences for end-of-life care have been limited to persons with severe physical illness (41, 42), residents of nursing homes (43), and the recently hospitlatized (44), or have assessed preferences for only single interventions such as CPR (44, 45). Among severely ill patients (advanced cancer, congestive heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) results have been mixed (41, 42). Persons with decline in physical functioning were more likely to accept treatment even if the outcome was predicted to be a diminished state of health (42). Subsequent study of the same cohort incorporated the trade off of burden of treatment with potential outcomes of treatment (41). The proportions of persons who would undergo therapy with a given likelihood of death or disability were similar over the course of the follow-up, but individuals were less likely to want burdensome treatment over time. Greater functional disability and poor quality of life was associated with decreased willingness to undergo treatment (41, 42). McParland and coworkers studied the preferences of nursing home residents for life-sustaining treatment over a 2-year interval, finding no association of change in preferences with physical functioning (43). Carmel and colleagues interviewed a sample of 1138 persons aged 70 years and older living in the community in Israel three times over 2 years (45). At each interval, approximately 70% of the sample did not change their preferences for aggressiveness of care while the remainder was split between wanting more care or wanting less. Among persons who declined life-sustaining treatment at baseline, 87% continued to decline treatment 2 years later (45). Recognizing that negative findings are difficult to generalize, we did not find an association of change in mental or physical health (as measured by the SF-36) with change in preferences for potentially life-sustaining treatment. Perhaps because physicians understand the course of disease and the nature of potentially life sustaining treatments better, in this cohort, factors other than age, physical functioning, and mental health appear to play a role in transitions between categories of potentially life-sustaining treatments.

The treatment options offered at the end of life fell into preference categories that were clinically meaningful. Our latent transition analysis sharpens the finding the focus on the role of advanced directives aside from its association with preference category. Given that physicians without advance directives were more likely to change to the more aggressive category than to the least aggressive category over time, the process of documenting specific wishes may make decision making more deliberate, leading to more stability of preferences. Among physicians, advance directives appear to be used to signify what one does not want rather than what one does want at the end of life. Older adults focus on preferences for perceived outcomes of serious illness rather than in terms of preferences for specific treatment options (46). Refocusing advance directives on delineation of acceptable health states (i.e., the outcomes of treatment) instead of preferences for specific medical interventions might better capture end-of-life care goals (47).

We believe that our study suggests that while physician-respondents were relatively stable in their preferences, persons without an advance directive and who desired the most aggressive treatment at baseline exhibited the most changeable preferences. We did not find evidence that changing mental or physical health were strongly associated with preferences for care. Persons who express a desire for aggressive treatment and those who have not communicated their wishes with a more formal written document (advance directive) may require frequent clinical re-evaluation to assess whether wishes have changed. We are carrying out open-ended interviews of respondents to understand the rationale for preferences for end-of-life care, to evaluate how and why preferences might change, and to determine whether the focus on potentially life-sustaining treatment in advance directives might be redirected to more salient domains such as values or outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. Wittink was supported by an NIMH Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (MH073658). The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study was supported by grants AG01760, DK02856, and DK07732 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland. The PI had full access to the data and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors have a conflict of interest to declare.

Role of the sponsor: The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients' perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281(2):163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynn J, Teno JM. Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;126:97–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-2-199701150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Baskin SA, Morris J, Meier DE. Treatment of the dying in the acute care hospital. Advanced dementia and metastatic cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(18):2094–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-of-life care? opinions of bereaved family members. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo JJ, Straton J, Klag M, et al. Life-sustaining treatments: what do physicians want and do they express their wishes to others? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(7):961–969. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straton J, Wang NY, Meoni L, et al. Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(4):577–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klag MJ, He J, Mead LA, Ford DE, Pearson TA, Levine DM. Validity of physicians' self-reports of cardiovascular disease risk factors. Annals of Epidemiology. 1993;3(4):442–447. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90074-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas CB. Observations on some possible precursors of essential hypertension and coronary artery disease. Bull Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1951;89:419–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klag M, Wang N, Meoni L, et al. Coffee intake and risk of hypertension: the Johns Hopkins precursors study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(6):657–662. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.6.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klag M, Ford D, Mead L, et al. Serum Cholesterol in Young Men and Subsequent Cardiovascular Disease. New Englan Journal of Medicine. 1993;328:313–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emanuel L, Emanuel E. The medical directive: A new comprehensive advance care document. JAMA. 1989;261:3288–3293. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.22.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer G, Alpert H, Stoeckle J, Emanuel L. Can goals of care be used to predict intervention preferences in an advance directive? Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(7):801–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emanuel LL, Emanuel EJ, Stoeckle JD, Hummel LR, Barry MJ. Advance directives: stability of patients' treatment choices. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1994;154:209–217. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Resource Center for Health Assessment A. (New England Medical Center) How to Score the MOS 36-Item (Short Form Health Survey SF-36) 1991

- 16.Stewart AL, Ware JE, editors. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHorney CA. Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 health survey. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:571–583. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS Short-form General Health Survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stadnyk K, Calder J, Rockwood K. Testing the measurement properties of the Short Form-36 health survey in a frail elderly population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:827–835. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyons R, Perry I, Littlepage B. Evidence for the Validity of the Short-form 36 Questionnaire (SF-36) in an Elderly Population. Age Ageing. 1994;23:182–184. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.3.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singleton N, Turner A. Measuring patients' views of their health. SF 36 is suitable for elderly patients. British Medical Journal. 1993;307(6896):126–127. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6896.126-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care. 1991;29(2):169–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McHorney C, Ware J, Raczek A. The MOS 36-Item Short Form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vermunt JK, Magidson J. In: Latent class analysis. Lewis-Beck MS, Bryman A, Liao TF, editors. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Sciences Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reboussin BA, Reboussin DM, Liang KY, Anthony JC. Latent transition modeling of progression of health-risk behavior. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1998;33(4):457–478. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3304_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung H, Park Y, Lanza ST. Latent transition analysis with covariates: Pubertal timing and substance use behavior in adolescent females. Stat Med. 2005;24:2895–2910. doi: 10.1002/sim.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum liklihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm with discussion. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velicer WF, Martin RA, Collins LM. Latent transition analysis for longitudinal data. Addiction. 1996;91:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen S, Kievit J, Nooij M, Stiggelbout A. Stability of Patients' Preferences for Chemotherapy: The Impact of Experience. Medical Decision Making. 2001;21:295–306. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menon AS, Campbell D, Ruskin P, Hebel JR. Depression, hopelessness, and the desire for life-saving treatments among elderly medically ill veterans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;8(4):333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee M, Ganzini L. The effect of recovery from depression on preferences for life-sustaining therapy in older patients. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49(1):M15–M21. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.m15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blank K, Robison J, Doherty E, Prigerson H, Duffy J, Schwartz HI. Life-sustaining treatment and assisted death choices in depressed older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(2):153–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danis M, Garrett J, Harris R, Patrick DL. Stability of choices about life-substaining treatments. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;120(7):567–573. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-7-199404010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenfeld KE, Wenger NS, Phillips RS, et al. Factors associated with change in resuscitation preference of seriously ill patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1996;156(14):1558–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eggar R, Spencer A, Anderson D, Hiller L. Views of elderly patients on cardiopulmonary resuscitation before and after treatment for depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatrty. 2002;17(2):170–174. doi: 10.1002/gps.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakim RB, Teno JM, Harrell FE, et al. Factors associated with do-not-resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;125(4):284–293. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-4-199608150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker RM, Schonwetter RS, Kramer DR, Robinson BE. Living wills and resuscitation preferences in an elderly population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155(2):171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fried TR, Van Ness PH, Byers AL, Towle VR, O'Leary JR, Dubin JA. Changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among older persons with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4):495–501. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:890–893. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McParland E, Likourezos A, Chichin E, Castor T, Paris BE. Stability of preferences regarding life-sustaining treatment: a two-year prospective study of nursing home residents. Mt. Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2003;70(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ditto PH, Jacobson JA, Smucker WD, Danks JH, Fagerlin A. Context changes choices: A prospective study of the effects of hospitalization on life-sustaining treatment preferences. Medical Decision Making. 2006;26:313–322. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmel S, Mutran EJ. Stability of elderly persons' expressed preferences regarding the use of life-sustaining treatments. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenfeld KE, Wenger NS, Kagawa-Singer M. End-of-life decision making. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:620–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenfeld KE, Wenger NS, Kagawa-Singer M. End-of-life decision making: A qualitative study of elderly individuals. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:620–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.