Abstract

The kinetic resolution of racemic cis-4-phenyl- and cis-4-tert-butyl-3-hydroxy-β-lactam derivatives with 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III yielded paclitaxel and butitaxel analogues with high diastereoselectivity. The results demonstrated that the tert-butyldimethylsilyl protecting group at the C3-hydroxy group of the β-lactams provided optimum kinetic resolution in comparison with the sterically less demanding triethylsilyl group and the larger triisopropylsilyl group. In addition, it was found that the C4 β-lactam substituents also influenced diastereoselectivity. The C4 tert-butyl-β-lactams provided better diastereoselectivity than the corresponding C4 phenyl β-lactams.

Introduction

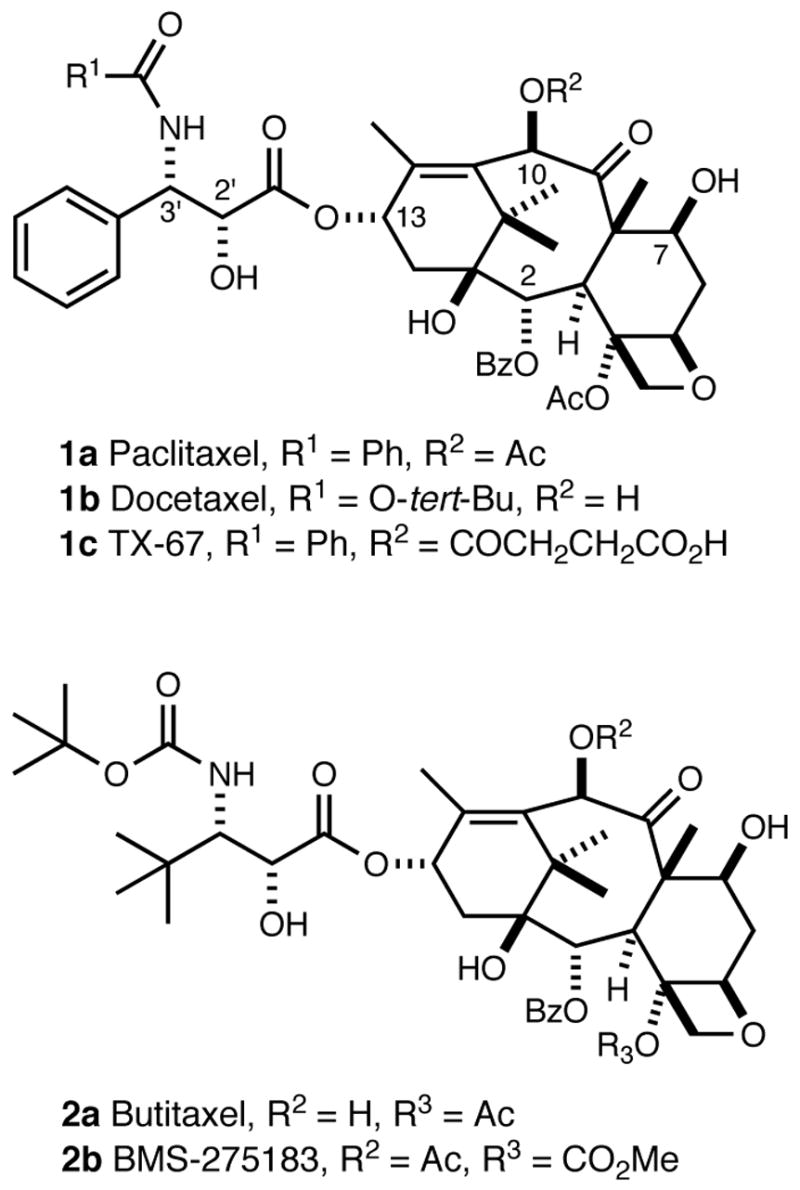

Paclitaxel (1a, Taxol®, Figure 1), a cytotoxic agent from the bark of the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia),1 exerts its activity by alteration of tubulin dynamics.2 Paclitaxel and its semisynthetic analogue docetaxel (1b, Taxotere®, Figure 1) are effective agents for the treatment of ovarian and breast cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and non-small cell lung cancer.3 The continued evaluation of new analogues is important because of paclitaxel drug-resistance, the inability of paclitaxel to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and its lack of oral bioavailability.4

Figure 1.

Structures of paclitaxel (1a), docetaxel (1b), Tx-67 (1c), butitaxel (2a), and BMS-275183 (2b).

In the course of structure-activity relationship studies, a series of highly potent second-generation analogues have been developed that overcome some of the deficiencies of paclitaxel.5 For example, it has been reported that BMS-275183 (2b, Figure 1), a derivative of butitaxel (2a, Figure 1),6,7 is orally bioavailable,8 and that TX-67 (1c, Figure 1) is able to cross the BBB in situ.9

Typically, paclitaxel analogues have been prepared by semisynthesis from baccatin III derivatives using non-racemic β-lactams, which serve as the precursors for the C13 N-acyl-3′-phenylisoserine side chain. The asymmetric ester enolate-imine cyclocondensation or enzyme-catalyzed resolutions are excellent methods to prepare enantiopure (3R,4S)-β-lactams.10–14 However, several groups have reported the synthesis of paclitaxel analogues through kinetic resolution using racemic cis-β-lactams with moderate to high diastereoselectivities.8,15–17 Recently, dynamic kinetic resolution of racemic 3-oxo-4-phenyl-β-lactam was achieved by recombinant E. coli, overexpressing yeast reductase Aralp.18 Holton was the first to disclose the kinetic resolution of N-benzoyl- and N-Boc-4-phenyl-3-triethylsilyloxy-β-lactams with the lithium alkoxide of 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III and 10-deacetyl-7,10-ditriethylsilylbaccatin III and reported diastereoselectivities of 6:1 and 100% respectively.15 Excellent kinetic resolution was also observed by Ojima and co-workers when they employed O-ethoxyethyl-protected 3-hydroxy-4-trifluoromethyl-β-lactams in this reaction.16 During these studies, it was found that variation of the baccatin III substituents typically had little effect on the stereoselectivity of the reaction. However, the kinetic resolution with N-Boc-3-triethylsilyloxy-4-tert-butyl-β-lactam was influenced by the structure of the baccatin III derivative.8 Reaction between N-Boc-4-tert-butyl-3-triethylsilyloxy-β-lactam and 7-O-diisopropylmethoxysilylbaccatin III provided a 3:1 diastereomeric ratio, whereas the reaction with a 7-deoxy-9β-dihydro-9,10-acetal-baccatin III yielded only one diastereoisomer.17

We surmised from these studies that the structure of the β-lactam plays a major role in controlling the stereoselectivity of the kinetic resolution and that this effect would warrant some further study. We therefore decided to investigate in more detail the influence of the β-lactam substituents on the outcome of the kinetic resolutions with 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III.

Results and Discussion

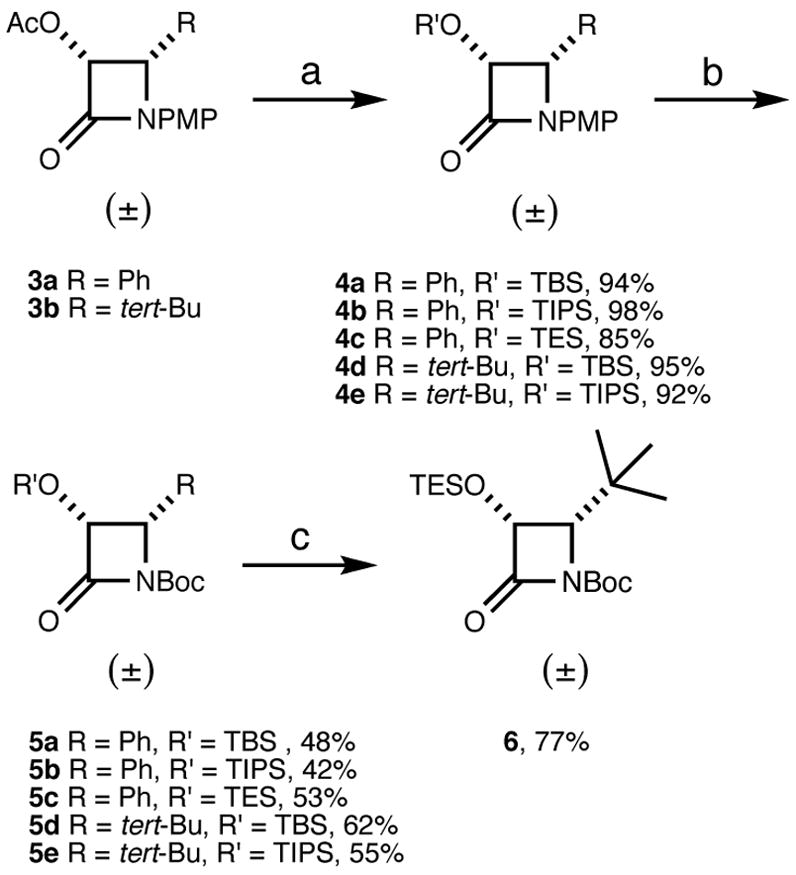

The synthesis of the racemic β-lactams 5 and 6 is shown in Scheme 1. The 4-phenylazetidin-2-one 3a and the 4-tert-butylazetidin-2-one 3b were prepared according to reported procedures.8 The acetyl group on 3 was removed with lithium hydroxide in acetone (for 3a) or potassium carbonate in methanol (for 3b), followed by protection with a trialkylsilyl chloride to furnish 3-trialkylsilyloxy-β-lactams 4a–e in high to excellent yields.19,20 The 4-methoxyphenyl moiety (PMP) of 4 was removed oxidatively with ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN),21 and then treated with tert-butyl dicarbonate to afford racemic 3-trialkylsilyloxy-4-phenylazetidin-2-ones 5a–c and 3-trialkylsilyloxy-4-tert-butylazetidin-2-ones 5d–e. 3-Triethylsilyloxy-4-tert-butylazetidin-2-one 6 was prepared from 5d by removal of the tert-butyldimethylsilyl protecting group with HF-pyridine, followed by triethylsilyl protection in 77% yield.

Scheme 1.

(a) i. LiOH in acetone or K2CO3 in MeOH; ii. R′SiCl, imidazole/DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; (b) i. Ce(NH4)2(NO3)6, aq CH3CN, −20 °C; ii. (Boc)2O, diisopropylethylamine, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; (c) i. HF-Py in Py, 0 °C to rt; ii. TESCl, imidazole, CH2Cl2, rt.

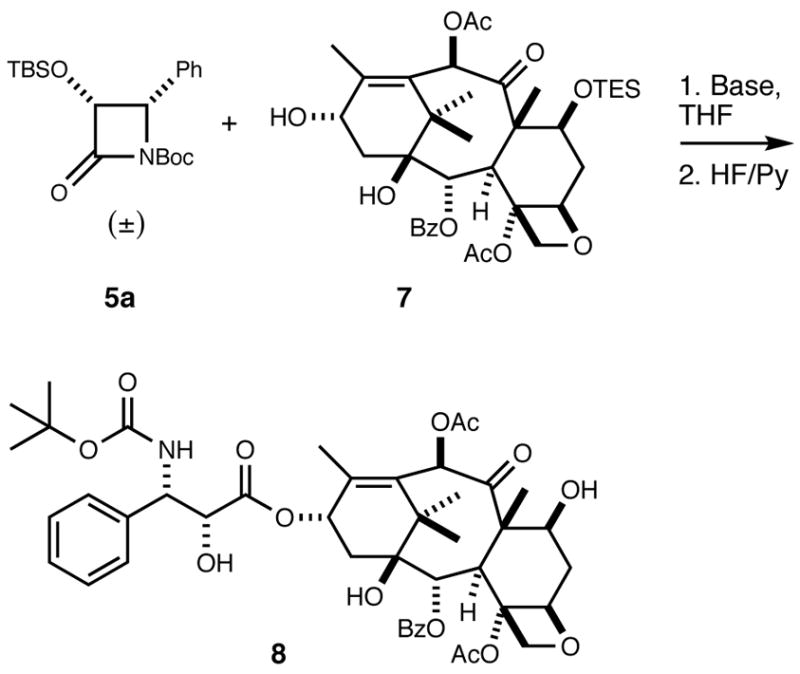

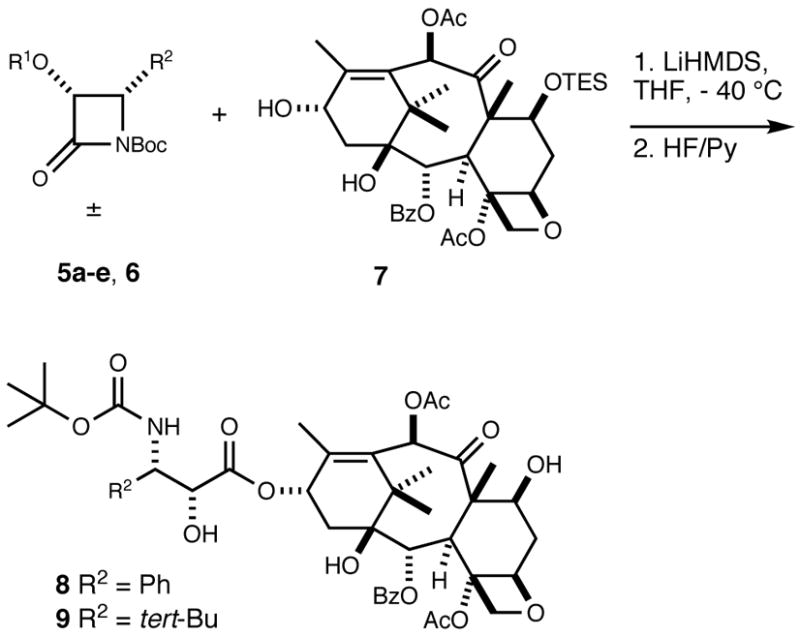

First, we investigated the kinetic resolution between racemic 4-phenyl-2-azetidinone 5a and 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III (7)22 under several different reaction conditions (Table 1). The resulting reaction products were subsequently treated with hydrogen fluoride in pyridine to furnish 10-acetyldocetaxel (8, Scheme 2). The isomeric ratios of 8 were determined by HPLC analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results from reactions of β-lactam 5a with 7 to furnish 8 under varied reaction conditions (Scheme 2).

| Entry | Lactam Equiv | Base Equiv | Reaction Temp (°C) | Yield (%) 8a | Isomeric ratiob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 1.5 LiHMDS | − 40 | 81 | 41 : 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 1.5 LiHMDS | − 40 to 0 | 82 | 36 : 1 |

| 3 | 4 | 1.5 LiHMDS | 0 | 84 | 34 : 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 1.5 LiHMDS | − 40 to 0 | 46 | 32 : 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 1.5 NaHMDS | − 40 to 0 | 62 | 7 : 1 |

Yields for two steps;

The isomeric ratio (2′R,3′S): (2′S,3′R) was determined by HPLC.

Scheme 2.

The results for the kinetic resolution are shown in Table 1. It was found that the diastereoselectivity of the reaction decreased slightly with an increase in reaction temperature (see entries 1, 2, and 3). Although the stereoselectivity was not significantly influenced, the yield dramatically decreased when the amount of 5a was reduced from 4 to 2 equivalents (entries 2 and 4). It has been hypothesized that chelation between the C13 lithium alkoxide of the baccatin III derivative and the carbonyl group of the β-lactam is important for the high diastereoselectivity.16 We therefore replaced LiHMDS with NaHMDS (entry 5) to study the effect of the presumably less chelating C13 sodium alkoxide on diastereoselectivity. Under these conditions, we noted a marked decrease in stereoselectivity and yield confirming the hypothesis (see entries 2 and 5) that chelation is important for high diastereoselectivity.

We next investigated the effects of different substituents at the β-lactam skeleton on the kinetic resolution (Table 2). Since it had been previously reported that the 1-tert-butoxycarbonyl group was important to generate high diastereoselectivity in the kinetic resolution, we retained this group in our experiments.15,16 We first probed the effects of different 3-hydroxylsilyl protecting groups. Reactions of β-lactams 5a–e and 6 with 7 were carried out using the conditions of entry 1, in Table 1. The results are shown in Table 2. As expected, it was found that the large triisopropylsilyl protecting group (entry 1) provided higher stereoselectivity than the smaller triethylsilyl group (entry 3). However, the tert-butyldimethylsilyl group proved to be optimal (entry 2), providing a 41:1 ratio of diastereoisomers. The results imply that the size of the C3-hydroxyl protecting group influences diastereoselectivity and that the tert-butyldimethylsilyl group, which is more sterically demanding than the triethylsilyl group, but smaller than the triisopropylsily protecting group, was optimal in this sequence of reactions.

Table 2.

Results of reaction between β-lactams 5a–e, 6 and 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III (7, Scheme 3) for the formation of 8 (entries 1–3) and 9 (entries 4–6).

| Entry | R1 | R2 | Yield (%)a | Isomeric ratiob |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TIPS | Ph | 80 | 32 : 1 |

| 2c | TBS | Ph | 81 | 41 : 1 |

| 3 | TES | Ph | 84 | 10 : 1 |

| 4 | TIPS | tert-butyl | 76 | 57 : 1 |

| 5 | TBS | tert-butyl | 84 | 82 : 1 |

| 6 | TES | tert-butyl | 78 | 40 : 1 |

Yields of 8 (entries 1–3), and of 9 (entries 4–6) for two steps; ;

The isomeric ratio (2′R,3′S) : (2′S,3′R) was determined by HPLC;

Same as entry 1, Table 1.

We also examined the effects of different substituents at the C4 position towards resolution. As is illustrated in Table 2, we observed increased stereoselectivity for the reaction of 4-tert-butyl β-lactam 5d (entry 5) with 7 compared to the reaction of 4-phenyl β-lactam 5a with 7 (entry 2), which indicates that the size of the C4 substituent also influences diastereoselectivity. To evaluate whether the C3-hydroxy protecting groups have an effect for the 4-tert-butyl β-lactam derivatives, we replaced the tert-butyldimethylsilyl with the larger triisopropylsilyl group (entry 4) and the smaller triethylsilyl group (entry 6). Again, it was found that the triisopropylsilyl group provided higher diastereoselectivity than the triethylsilyl group, while the tert-butyldimethylsilyl group afforded the best resolution. These results suggest that at least one sterically demanding substituent is required at either C3 or C4 for satisfactory selectivity. This is supported by Ojima’s observation that 3-triisopropylsilyloxy-4-trifluoromethyl, 3-triisopropylsilyloxy-4-isobutyl and 3-triisopropylsilyloxy-4-isobutenyl β-lactams gave high yields and stereoselectivities for the kinetic resolution with modified baccatins.19

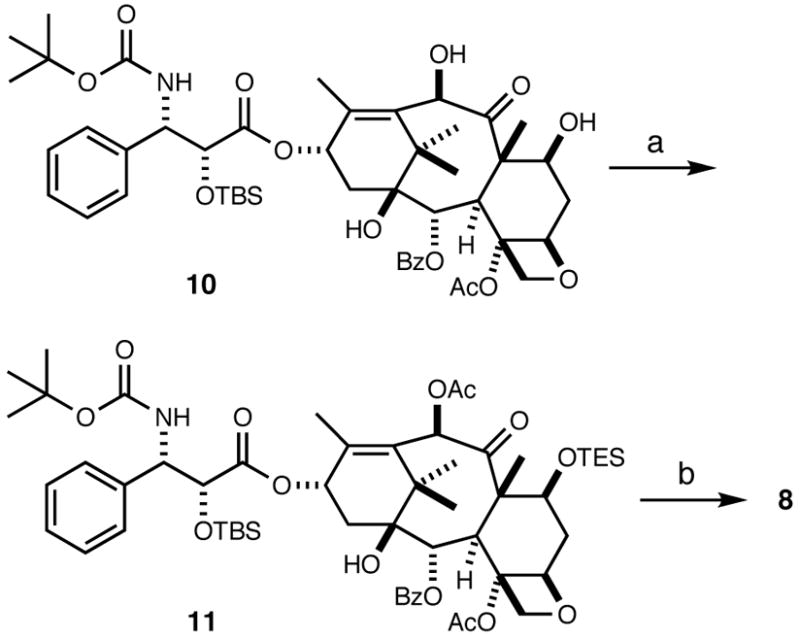

To unambiguously prove the identity of the major product, we synthesized 10-acetyldocetaxel (8) as shown in Scheme 4. Starting from 2′-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyldocetaxel (10), prepared from commercially available docetaxel, triethylsilyl protection of the C7-hydroxy group followed by acylation of the C10-hydroxy group with acetic anhydride afforded intermediate 11, which was converted to 10-acetyldocetxel (8) by treatment with hydrogen fluoride in pyridine. Spectral data and HPLC retention times were identical for the products obtained by both methods, confirming that the major diastereomer obtained in the kinetic resolution had the same (2′R,3′S) configuration as docetaxel. 10-Acetylbutitaxel (9) has been synthesized previously and matched the reported spectroscopic data.23

Scheme 4.

(a) i. TESCl, imidazole, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; ii. acetic anhydride, DMAP, pyridine, 0 °C to rt (96 %); (b) HF-Py in pyridine, 0 °C to rt (90 %).

In conclusion, a systematic study of the kinetic resolution of racemic 4-phenyl-and 4-tert-butyl-β-lactams with 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III was carried out. It was found that the size of the silyl protecting groups at the 3-hydroxy moiety of β-lactams had an important influence on the diastereoselectivity of the resolution. The tert-butyldimethylsilyl protecting group was found to be superior to the smaller triethylsilyl group and the larger triisopropylsilyl group in the reactions investigated. The size of the 4-substituents at the β-lactams also influenced diastereoselectivity. The sterically more demanding 4-tert-butyl β-lactams gave rise to better kinetic resolution than the corresponding 4-phenyl β-lactams. Therefore, it can be concluded that high stereoselectivity can be obtained either by using sterically demanding C3-hydroxy protecting groups or C4 substituents.

Experimental Section

HPLC conditions used in Tables 1 and 2

Jupiter 5 μ C4-reversed phase column (10 × 250 mm) from Phenomenex USA, employing a gradient of water-acetonitrile (0–70%, v/v) with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid as the solvent system with a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min for 70 min. Average retention time for the major isomer (2′R,3′S)-8 = 46.56 min; minor isomer (2′S,3′R)-8 = 45.98 min. Average retention time for the major isomer (2′R,3′S)-9 = 47.92 min; minor isomer (2′S,3′R)-9 = 46.70 min.

cis-(±)-1-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-3-tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy-4-phenylazetidin-2-one (5a)23

Yield = 48%, yellow solid; mp = 93–95 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) delta; −0.15 (s, 3H), 0.06 (s, 3H), 0.65 (s, 9H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 5.04–5.07 (m, 2H), 7.27–7.37 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ−5.0, −4.5, 18.2, 25.6 (3C), 28.2 (3C), 62.4, 77.7, 83.8, 128.2 (2C), 128.4 (2C), 128.6, 134.3, 148.3, 166.6; HRMS (ES+) m/z calcd for C20H31NO4SiNa [MNa+] 400.1920, found 400.1910.

Synthesis of cis-1-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl)-3-triethylsilyloxy-4-tert-butylazetidin-2-one (6)

To a solution of 5d (115.0 mg, 0.3216 mmol) in pyridine (6.0 mL) were added 12 drops of a HF-pyridine solution dropwise at 0 °C under argon. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min and then another 20 drops of HF-pyridine solution were added dropwise at the same temperature. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature overnight and then diluted with EtOAc, washed with aqueous NaHCO3, water and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid. To a solution of the solid thus obtained, was added imidazole (43.8 mg, 0.643 mmol), TESCl (108 μL, 96.9 mg, 0.643 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5.0 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred under argon at room temperature for 24 h, diluted with CH2Cl2 and quenched with water (50 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash column chromatography (silica gel) with EtOAc/hexanes afforded 96 mg (77%) of a colorless oil. The compound showed spectroscopic properties in agreement with the literature.8

Synthesis of 10-Acetyldocetaxel (8) and 10-Acetylbutitaxel (9)

A solution of 5 or 6 (0.1696 mmol) and 7-O-triethylsilylbaccatin III (7, 30.0 mg, 0.042 mmol) in THF (2.5 mL) under argon was cooled to −40 to 50 °C and a solution of LiHMDS (64 μL, 0.064 mmol, 1.0 M in THF) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 50 min at the same temperature and then quenched with saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid. To a solution of the solid thus obtained in pyridine (2.0 mL) under argon were added 8 drops of a HF-pyridine solution dropwise at 0 °C under argon. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at the same temperature, and then another 10 drops of HF-pyridine solution were added dropwise. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature overnight, diluted with EtOAc (30 mL), washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution, water and brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Flash column chromatography (silica gel) with EtOAc/hexanes afforded the product.

10-Acetyldocetaxel (8)

Yield = 46–84%, off-white solid. The compound showed spectroscopic properties in agreement with the literature.24

10-Acetylbutitaxel (9)

Yield = 78–84%, off-white solid. The compound showed spectroscopic properties in agreement with its structure.25

Supplementary Material

Full experimental procedures and characterization data for compounds 4a-4e, 5a-5e, 8, and 11, and HPLC traces for the experiments in Tables 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Scheme 3.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the National Cancer Institute for financial support of this research (NIH CA82801 and NIH CA105305) and Tapestry Pharmaceuticals (Boulder, CO) for a generous gift of 10-deacetylbaccatin III. J. T. S. was a recipient of an American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education predoctoral fellowship and a Department of Defense predoctoral fellowship (Grant DAMD 17-99-1-9243). We also thank Christopher Schneider for his help with the HPLC.

References

- 1.Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:2325–2327. doi: 10.1021/ja00738a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For review: Zhou J, Giannakakou P. Curr Med Chem - Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:65–71. doi: 10.2174/1568011053352569.

- 3.For review: Spencer CM, Faulds D. Drugs. 1994;48:794–847. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448050-00009.

- 4.Ge H, Vasandani V, Huff JK, Audus KL, Himes RH, Seelig A, Georg GI. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:433–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For review: Kingston DGI, Jagtap PG, Yuan H, Samala L. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 2002;84:53–225. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6160-9_2.

- 6.Ali SM, Hoemann MZ, Aubé J, Mitscher LA, Georg GI, McCall R, Jayasinghe LR. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3821–3828. doi: 10.1021/jm00019a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali SM, Hoemann MZ, Aubé J, Georg GI, Mitscher LA. J Med Chem. 1997;40:236–241. doi: 10.1021/jm960505t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mastalerz H, Cook D, Fairchild CR, Hansel S, Johnson W, Kadow JF, Long BH, Rose WC, Tarrant J, Wu MJ, Xue MQ, Zhang GF, Zoeckler M, Vyas DM. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:4315–4323. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00495-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice A, Liu Y, Michaelis ML, Himes RH, Georg GI, Audus K. J Med Chem. 2005;48:832–838. doi: 10.1021/jm040114b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For review: Boge TC, Georg GI. The Medicinal Chemistry of β-Amino Acids: Paclitaxel as an Illustrative Example. In: Juaristi E, editor. Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Amino Acids. Wiley-VCH; New York: 1997. pp. 1–43.

- 11.Kayser MM, Mihovilovic MD, Kearns J, Feicht A, Stewart JD. J Org Chem. 1999;64:6603–6608. doi: 10.1021/jo9900681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayser MM, Yang Y, Mihovilovic MD, Feicht A, Rochon FD. Can J Chem. 2002;80:796–800. [Google Scholar]; Yang Y, Wang FY, Rochon FD, Kayser MM. Can J Chem. 2005;83:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel RN, Howell J, Chidambaram R, Benoit S, Kant J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:3673–3677. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr JC, Al-Azemi TF, Long TE, Shim JY, Coates CM, Turos E, Bisht KS. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:9147–9160. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holton RA, Biedinger RJ, Boatman PD. Semisynthesis of Taxol and Taxotere. In: Suffness M, editor. Taxol ® Science and Applications. CRC; Boca Raton, Fl: 1995. pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojima I, Slater JC. Chirality. 1997;9:487–494. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1997)9:5/6<487::AID-CHIR15>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda Y, Uoto K, Iwahana M, Jimbo T, Nagata M, Atsumi R, Ono C, Tanaka N, Terasawa H, Soga T. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:3209–3215. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Drolet M, Kayser MM. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:2748–2753. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin SN, Geng XD, Qu CX, Tynebor R, Gallagher DJ, Pollina E, Rutter J, Ojima I. Chirality. 2000;12:431–441. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(2000)12:5/6<431::AID-CHIR24>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spletstoser JT, Flaherty PT, Himes RH, Georg GI. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6459–6465. doi: 10.1021/jm030581d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Georg GI, Kant J, Gill HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1129–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denis JN, Greene AE, Guénard D, Guéritte-Voegelein F, Mangatal L, Potier P. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:5917–5919. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ojima I, Sun CM, Zucco M, Park YH, Duclos O, Kuduk S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4149–4152. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangatal L, Adeline MT, Guénard D, Guéritte-Voegelein F, Potier P. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:4177–4190. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Compound 9 showed spectroscopic properties in agreement with the data reported: Holton RA, Chai K-B, Idmoumaz H, Nadizadeh H, Rengan K, Suzuki Y, Tao C. US 55739362. 1998.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full experimental procedures and characterization data for compounds 4a-4e, 5a-5e, 8, and 11, and HPLC traces for the experiments in Tables 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.