Abstract

Context

Community-based resources are considered a critical part of the American healthcare system. However, studies evaluating the effectiveness of such resources have not been accompanied by rigorous explorations of the perceptions or experiences of those who use them.

Objective

In this paper, we aim to understand and classify types of negative perceptions that low-income parents have of community resources. This objective originated from a series of unexpected findings, which emerged during the analysis of qualitative data, initially collected for other purposes.

Methods

In-depth qualitative interviews with urban low-income parents. Themes emerged through a grounded theory analysis of coded interview transcripts. Interviews took place in two different cities as part of two studies with distinct objectives.

Results

We completed 41 interviews. Informants often perceived their interactions with people and organizations as a series of tradeoffs; and important choices, often as decisions between two suboptimal options. Seeking help from community resources was seen in that context. The following specific themes emerged: 1) Engaging with services sometimes meant subjecting oneself to requirements perceived as unnecessary; and in the extreme, having to adopt the value systems of others. 2) Accepting services was sometimes perceived as a loss of control over one's surroundings, which in turn was associated with feelings of sadness, helplessness or stress. 3) Individuals staffing community agencies were sometimes seen as judgmental or intrusive; and when many services were accessed concurrently, information sometimes became overbearing or a source of additional stress; and 4) Some services, or advice received as part of such services, were perceived as unhelpful because they were too generic or formulaic.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that definable patterns of negative perceptions of community resources may exist among low-income parents. Quantifying these perceptions may help improve the client-centeredness of such organizations, and may ultimately help reduce barriers to engagement.

Keywords: community resources, access to care, qualitative interviews, qualitative research, vulnerable populations

Introduction

The integration of community resources with healthcare delivery is an important component of quality medical care. According to the MacColl Institute's Chronic Care Model, community programs can support and expand the health system's ability to provide service, not only for the chronically ill, but also for healthy individuals for whom prevention is a principal goal of care (1-3). In recent years, numerous studies demonstrating the effectiveness of community-based services – such as early intervention for children with developmental problems (4-6), home visitation programs (7-9), and early learning programs (10, 11) – have appeared in the medical literature. Additional commentaries have been published on the promise of such services as medical-legal advocacy partnerships (12) and community-integrated primary care (13). In its latest edition, the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures Guidelines highlighted access to community resources as one of the principal themes of quality pediatric health supervision (14).

Despite the acceptance of community resources as important components of healthcare, such resources have not been examined with the same set of standards – relative to their shortcomings or negative perceptions – as more traditional aspects of medicine. Whereas the medical literature is replete with evidence concerning families’ negative perceptions on a variety of elements of pediatric care – for example, dissatisfaction among families of children with special healthcare needs (15), barriers to acceptance of certain vaccines (16), or the fear and vulnerability that parents feel during the evaluation of a febrile infant (17) – we could find few similar studies pertaining to community-based resources.

The present analysis aims to classify the types of negative perceptions or experiences that occur when low-income families consider engaging with community resources established for their benefit. The analysis presented is based on a series of unexpected findings from in-depth qualitative interviews with urban low-income parents in two geographic locales. Through the analysis of these conversations, and presentation of themes derived from them, we aim to generate hypotheses for future research regarding how community resources may be better tailored to clients’ needs, and how client utilization and satisfaction can be maximized.

Methods

Study overview, qualitative methodology and how unexpected findings emerged

We conducted 41 interviews. Thirteen interviews were conducted in Seattle, WA between April 2002 and January 2003 for the original purpose of exploring how families access early learning resources for their children. Twenty-eight were conducted in Boston, MA between November 2004 and May 2006 for the original purpose of exploring how low-income mothers perceive experiences of adversity and stress.

Both sets of interviews were guided by open-ended questions, the majority of which were not specific to the stated research objectives (Table). Such contextual questions (for example, “Please tell me about your family.”) were designed to encourage individuals to open up and express experiences and perceptions in their own terms – an accepted goal of ethnographic-style qualitative interviewing (18). Therefore, although the two sets of interviews had distinct original objectives, they used an identical set of questions, not specific to the orginial research objectives, to achieve open dialogue. Because of this interviewing technique, both sets of interviews led to a series of unexpected discussions about participants’ negative perceptions of their interactions with an array of community and social services. The authors felt that because these findings were unexpected – and derived from questions common to both sets of interviews – combining the two datasets in a single analysis was methodologically sound, and consistent with existing literature on aggregating qualitative data (19-21).

Table.

Questions used in the interviewing process

| Contextual questions (common to Boston and Seattle Interviews) | Contextual questions were not specific to original research objectives at either site. Unexpected findings concerning community agencies emerged in response to these questions.* | ||

| 1. | Please tell me about your family (or your child). | ||

| 2. | What kinds of things do you like to do with your family when you're together? What kinds of things do you talk about? I'm curious to learn more about [name of a specific person in the family]. | ||

| 3. | You've described certain people in your family. How would you describe yourself? | ||

| 4. | Could you walk me through a typical day for you? | ||

| 5. | I've asked you some personal questions. How does that make you feel? | ||

| |

|

|

|

| Seattle | Boston Specific to community agencies | In the Boston cohort, questions regarding community agencies were formulated in an iterative fashion to clarify emerging themes. | |

| Tell me about some of your experiences with [community agency]. | |||

| Tell me about some of the relationships that you've had with [community agency] people. | |||

| |

|

|

|

| Questions specific to early learning | Questions specific to adversity and stress | ||

In the majority of interviews, responses to contextual questions touched upon original research objectives. Our interviewing technique was to pursue those objectives with simple prompts, such as “tell me more about that,” or “that's interesting to me.” Once unexpected themes regarding community agencies began to emerge, we applied the simple prompts to these emerging themes as well.

Participants and recruitment

Participants, often termed “informants” in qualitative research, were recruited from Head Start or other home visitation programs, outpatient pediatric clinics, and Women Infant and Children (WIC) offices. In Seattle, any mother or father was eligible to participate; in Boston, any mother or expectant mother was eligible. Effective communication in English was required for participation. As is typical in qualitative research, our sampling scheme was nonrandom and aimed to cover a range of relevant perspectives. We purposefully recruited informants from different geographic locales within the cities, informants with and without local family support, and informants with and without partners. Physicians, social workers, and home visitors in each venue were given a brief overview of the study's goals (as stated above), and identified potential participants by phoning them or informing them of the study during normal work-related interactions.

In the informed consent process at the time of the interview, informants were told that they would be asked general questions about themselves and their families. They were also informed, in intentionally vague terms, about the original objectives of each study – for example, how they think about getting what they need for their children (Seattle), or how they cope with the events of everyday life (Boston). They were also told that they would receive $25 for participating. All informants were asked permission to be contacted in the future so investigators could obtain feedback on study findings. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and the Boston University Medical Center approved this study.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted by one of the authors (MS; 24 interviews) and a research assistant (17 interviews), both of whom were trained in qualitative interviewing. Interviews lasted 45 to 90 minutes; they were audiotaped and transcribed. Two anthropologists independently assessed samples of the tapes to assure appropriate interviewing technique.

Data analysis

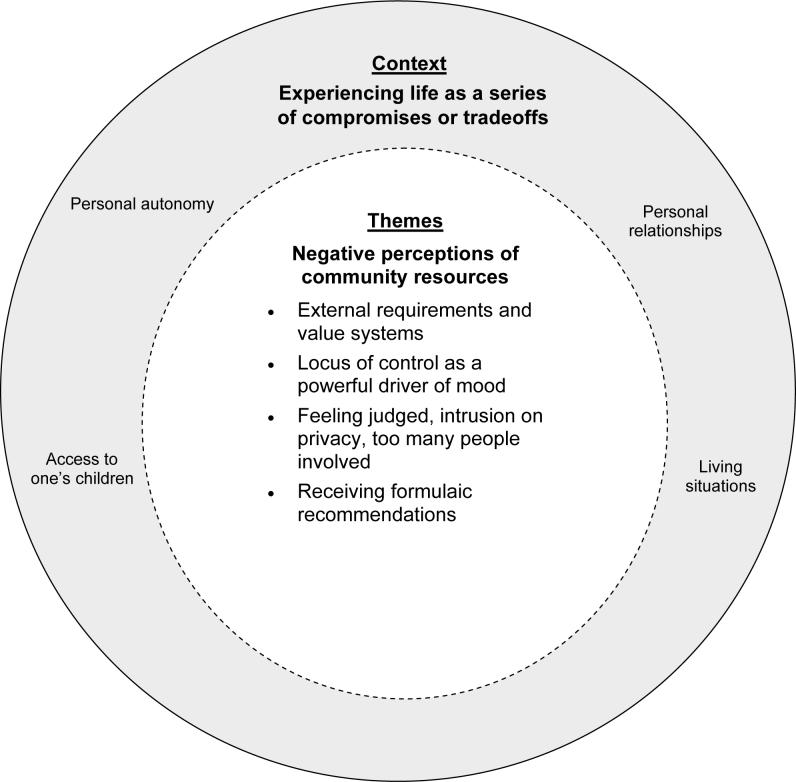

The open-ended interviewing structure permitted participants to speak for themselves, leading to the emergence of unexpected findings. It also permitted investigators to explore such findings without imposing researcher-derived constructs or preconceived hypotheses – a grounded theory approach to data analysis (18). As part of this approach, data derived from earlier time points (in both Seattle and Boston) were discussed and used to adapt interview questions (22). Through this process – and concurrent with data acquisition in Boston – we uncovered and developed themes related to negative perceptions of community services (Figure 1). Although the basic structure of our interviews did not change, interviewers began to probe more deeply into this topic as further relevant themes emerged – but never with the assumption that such experiences had to be negative.

Investigators reviewed each transcript independently, and then discussed the salient themes of each. Once all transcripts were discussed, investigators agreed upon a set of codes to capture the presence or absence of these themes in each transcript. Investigators (MS, KD, JL) then coded the transcripts independently and convened to assure uniform coding. Disagreements were resolved through discussion; transcripts were sorted into coded passages through the use of the Hyperresearch software package (Randolph, MA). Each coded passage was then reviewed by the investigators and categorized into final themes. Investigators also collected passages in which informants shared perspectives different from the central themes (23). We term these, “divergent cases.”

Data credibility

Data collection formally ended for the Boston interviews when the authors recognized that a set of recurrent themes, relevant to the initial study goal of exploring perceptions of stress and adversity, were identified and no new themes in this regard were evident (thematic saturation). In a similar fashion, thematic saturation was also ensured relative to the unexpected finding concerning community resources. The Seattle transcripts were then reviewed to look for any new themes relevant to experiences with community resources; none was discovered. Due to the unexpected nature of the findings, thematic saturation was unable to be confirmed independently for the Seattle cohort. We therefore performed an analysis, restricted to the Boston interviews (the larger of the two datasets, and the one in which the unexpected findings surfaced during prospective data collection), to assure the reliability of our findings.

We employed three, accepted techniques to ensure the validity of our data (24, 25). 1) Investigator triangulation: the three investigators who coded the data were from different disciplines and each read the transcripts independently before meeting to ensure consensus of all codes applied. We also compared the transcripts of the two different interviewers to look for systematic differences between them. 2) Expert triangulation: investigators convened three separate meetings in which the study's methodology, coding scheme, and results were presented to a group of health services researchers, to two social workers, and to three representatives from the community agencies under discussion. Meetings with researchers occurred as formal and informal sessions within an academic division of general pediatrics. Social work and community representative meetings occurred once the initial coding schema was created, with attendees chosen based on their relevant expertise. 3) Member checking: themes were shared with a subset of study subjects in the Boston cohort. To ensure subject confidentiality during data corroboration procedures, only general themes – as opposed to direct quotations – were shared and discussed.

Results

Population

Informants ranged in age from 19 to 45 years. All informants had incomes at or below the federal poverty level, and most had attended some high school. Of the 41 participants, two were fathers; one, an expectant mother; 38, mothers. Across the 41 total subjects, countries of origin included the US (n=22), China (n=2; Boston), Japan (n=1; Boston), the Dominican Republic (n=4; Boston), Haiti (n=2; Boston), Mexico (n=7; 5 from Seattle), Zambia (n=1; Boston), Ethiopia (n=1; Seattle) and Somalia (n=1; Seattle) – largely reflecting each city's demographics. The proportion of US born informants was nearly equivalent in both cohorts, as was the average informant age.

Reliability of Findings

Interviews conducted by the two interviewers were compared, and no systematic differences were discernable. Although the expert triangulation meetings helped investigators define their themes more specifically, themes did not change based on these meetings. After conducting member checking sessions with five informants, in which no changes were made to study findings, the investigators decided that additional sessions were unnecessary. The findings of the study did not change if we restricted the analysis to the Boston cohort.

Context: life as a series of compromises

Many informants perceived their lives as a series of compromises, or tradeoffs, and this perception provided the context to how they discussed their relationships with many community organizations (Figure 2). Compromises frequently involved the terms of a personal relationship, living situations, personal autonomy, access to one's children, or money. Many compromises took the form of power struggles, in which ceding control over certain aspects of one's life appeared the central issue.

¶1: It got to the point where it was always me saying one thing and him saying another, and it was like we got to meet halfway. And I was doing all the compromising, so once our relationship ended, I felt so much better. And when it ended, he still lived with me for a year. I should say once he moved out, things got better.

¶2: He's [former partner] much happier being out on the street, dealing. I mean he's a drug addict, he's a drug dealer. He's been in jail a lot of his life, over 10 years he's been in and out of jail. The past 5 years he hasn't been in jail, but I bailed him out of jail for $5000, so that he can see the baby [i.e. his baby] being born.

Many of our informants’ decisions appeared to require an explicit examination of an assumed drawback or a difficult choice between two suboptimal options. In the following passage, the informant discusses the drawbacks of enrolling her child in Head Start, and her concern that the need for childcare may be exposing her child to a suboptimal environment (¶3).

¶3: You can complain about it [i.e. the teachers not doing their jobs well], but not a whole lot would get done. Not a whole lot would come out of it because they're [publicly] funded, and if they had their own money, maybe they could hire better teachers or give them better training, but they're funded by someone else, so you get what you get.

Such a mindset of compromise provided a frame of reference regarding how many of the informants perceived their interactions with community services.

Themes: Negative perceptions to engagement with community-based resources

External requirements and value systems

One perceived disadvantage of accepting help from social services was the imposition of external requirements or structure. Although not restricted to homeless shelters, this perception was particularly apparent among informants requiring help for unstable housing situations. The informant in the example below used a mocking tone to parody the daily schedule in a homeless shelter, which she felt infringed on her autonomy (¶4).

¶4: So usually Monday, Tuesday Wednesday, we have meetings from 9:30 in the morning until 11:00, unless you have more stuff to say and it runs later. So we have to be there every day. We always have to participate. We always have to say our name, our room number and how we're doing that day, and then if we have any issues with the house. After we do that, I usually eat breakfast, get ready for the day, shower, depending on if I have appointments, doctors’ appointments.

One specific type of external requirement mentioned by a small number of informants was the imposition of other people's value systems (¶5). Informants generally saw such an imposition as necessary to endure, should the service be absolutely necessary. In the following example, the informant was required to attend bible study in her shelter.

¶5: I was living in a shelter, and the shelter has rules, like my curfew was 7 o'clock. Yeah, my curfew was 7 o'clock, and of course that shelter was just like a house, so like the lady, the owner is a Catholic, so Tuesdays and Thursdays we had to go to bible study, we had to do religious classes from about 10 to 3 o'clock, Tuesday and Thursday and it's compulsory whether you like it or not.

Locus of control as a powerful driver of mood

Among virtually all our informants, the perceived loss of control over one's life circumstances – whether at the hands of a social service organization, another individual, or uncontrollable circumstance – was seen to be associated with feelings of sadness, helplessness or stress (¶6).

¶6: I got trapped. You know how guys say they get trapped by babies. I think got trapped because I wanted to have an abortion, but he [father of the baby] wanted to have the kid...for me and for him. I got trapped. I should have listened to myself. But you know I take it one day at a time, hope for the best, expect the worst.

Conversely, taking control of one's circumstances, acknowledging errors in judgment, or assuming ownership of problems were perceived as empowering and served to alleviate demoralization or to positively reframe one's experience of adversity (¶7). The following informant relates her experience of discovering she was pregnant:

¶7: I walked out of the room [after discovering she was pregnant] with a smile on my face because I knew my life was never going to be the same. And I says to myself, “You know what, you have to smarten up. You have to take action. You have a little baby coming into the world. You can't be a screw-up like you usually are.” So I took a stand, got myself on SSI, got healthcare, went to all my appointments. I stopped doing drugs cold turkey.

For some of our informants, accessing certain services – or admitting that they needed services – represented a loss of control (¶8). This was particularly salient for housing or welfare services. This particular informant spoke of loss of control using the metaphor of “not having her life,” which also may be interpreted as a tradeoff or compromise.

¶8: You went through a lot of stuff like those Welfare Office people; they're very rude. So I don't have to deal with those if I didn't have her [her daughter]. But then I have her, and I have to deal with those people, and then I have to go the shelter and stuff. Every day-I didn't have my life. Every day, it's the people watching you, what you do, and they would tell you what you have to do.

For a few informants, accepting help (either from individuals or from agencies) conflicted with their source of pride. This perception, combined with a low expectation for what they would receive, was sometimes discussed as a barrier to accessing services. In the following case, the locus of control theme is linked to the previously mentioned finding regarding tradeoffs and compromise (¶9).

¶9: Because my mother raised me to not ask people for help because you should be able to do it yourself, at times, people would offer and whether I wanted to say yes or no, I would say no because thinking back to about how she raised me. If you got yourself into a situation or this is the problem, what would you do to get yourself out? Being able to depend on yourself and nobody else because a lot of times people can let you down so. So even when I did ask people for help, okay you have to know that people are willing to help you; it's okay to ask for help, and don't always let your pride stand in the way because if you do, that can keep you from doing whatever it is you need to do.

Judgment, intrusion, overload

Another theme among our informants was that they perceived some people working in the human services sector to be judgmental or intrusive; and that the aggregation of many services could be overbearing. One informant, for example, related her involvement with six or seven separate individuals, each of whom offered different advice (¶10).

¶10: A lot of voices telling you what to do...the case manager tell you to do that, and the house manager tell you to do this, then a lot of appointments, downtown appointments and then appointment for the case manager, the house manager, and then nutrition here, nutritionist, and then the two more social workers here and my case manager here. Can you imagine how many people I have to deal with? It was probably six-seven people.

Further, fulfilling the demands of one social worker often meant having to be late for a meeting with another; and in this context, the above informant reported feeling judged or patronized.

Apart from the time commitment of receiving certain services, a number of women felt that many services were not worth sacrificing their privacy (¶11).

¶11: I feel tied down being here like with the whole apartment situation. Right now I'm on assistance, and I don't want to be on assistance, but I have to be. I don't like people combing through my life with a comb. I don't like that. And that's what you have to do.

For some mothers, avoiding judgment by others – for example, negative assessments of their parenting skills by childcare providers – was linked to hardships in other aspects of their lives (¶12). In the passage below, the informant feels as though the Head start staff is going to think she is physically abusive to her child if they witness her yelling at her child, and this perception of being judged forces the informant to withdraw her child from the program.

¶12: As soon as we got to the door of the classroom, she would start crying. It was like, okay, we're doing this every day. I'm not sure what to do. But I can't yell at you [the child] because it's like that's not helping you. And then if I'm yelling at you as well, the teachers are going to look at it as if I'm threatening you, or I'm hitting her before she goes to school. And they used to think that. So at times I would keep her at home or at least try and talk to the teacher and at least to try and coach her...And after a while, it's like okay, I have to withdraw her because she's not going to stop crying until she can feel like she's comfortable.

Formuliac recommendations

A few informants related the experience of having been given advice that was not specific to them or information that they already knew (¶13).

¶13: It's like-I feel like they don't think I can do it. They give me those advice [sic] that I know already. I don't need to hear it again because I told myself those things and I know it.

A few informants also related the experience of having been given advice without having first been listened to. One informant used the metaphors of ‘slow’ and ‘fast’ to describe thoughtful and non-thoughtful social workers, respectively. Informants’ desire for individuals to listen to them was couched in terms not only of needing emotional support or friendship, but also of listening and understanding being a prerequisite for the provision of useful services, applicable to an individual's specific needs (¶14).

¶14: Sometimes you need a listener more than an advisor. You know what I'm saying. Sometimes social worker give you advice and that makes feel like they're pushing me to listen to them to-they're trying to give me an idea that this is what it is. This is what you should do. This gives me stress. But the social worker who sits there and try to slow down and see what I see in my anger and not give me advice and just listen. That's better to reduce my stress.

[Note: Because this passage may have multiple interpretations, the authors confirmed its meaning directly with the informant.]

Divergent cases

Although the purpose of this analysis was to describe specific perceptions that adversely affect engagement with community resources, we also discovered some favorable perceptions. Some informants, for example, related that certain child development programs helped them with issues that they had previously considered beyond the scope of such programs. Additionally, engagement with certain resources sometimes made them feel they were not alone is experiencing an adversity, as opposed to making them feel singled out (¶15). In such a way, they provided a positive juxtaposition to the medical system.

¶15: They [the Head Start teachers] talk with you. They joke with you. They make you feel that you're no different from anybody else. Sometimes doctors make you feel like you're different.

Lastly, many of our informants (like the following one, in her early twenties) spoke of meeting individuals unexpectedly who were particularly talented at their jobs, who were particularly helpful, or who went beyond what their job was perceived to entail (¶16).

¶16: Like [person's name] goes to appointments with me, to sign a contract with me when I got my apartment. That was a big help because I never get an apartment before; I didn't sign a contract before. You know, she's more like an adult to me.

Discussion

Among our informants, we uncovered a series of common themes, potentially important to informing a new direction of research, relevant to the delivery of client-centered, community-oriented healthcare. Our anchoring contextual finding was that many informants perceived their interactions with others as a series of tradeoffs or power struggles; and they reported a similar dynamic with social service agencies. Common to a number of our informants was the perception that accessing services from some agencies meant subjecting oneself to unnecessary requirements, including the imposition of external value systems. This phenomenon was sometimes interpreted as a loss of control over one's surroundings. Sometimes, services, or the advice informants received, were perceived as too generic or formulaic to be helpful; when many services were accessed concurrently, information sometimes became a source of additional stress.

Whereas many have written about community resources as a important component of healthcare (1, 2), studies evaluating the effectiveness of such resources have been unaccompanied by rigorous explorations of either their negative consequences or negative perceptions by those who use them. Although studies in the social work literature address such topics among specific populations such as homeless youth, veterans or African American women exposed to violence (26-28), to our knowledge our study is the first to systematically classify such perceptions among low-income urban parents with young children.

If community resources are taken to be a vital part of the greater healthcare system, such resources, we argue, should be examined with similar standards as more traditional aspects of healthcare, relative to their degree of client-centeredness. Key attributes of client-centeredness – a concept viewed by the Institute of Medicine as a key contributor to quality healthcare (29) – are respect for client values, preferences and needs; coordination and integration of services; access; and communication between clients and providers (30). Previous reports have demonstrated areas in need of improvement in healthcare relative to many of these domains (31-33). This report details the unexpected findings of interviews of low-income mothers that shed light on this issue as it relates to community-based services.

One may argue that many of the negative perceptions reported in this study are unavoidable. Resident safety in a homeless shelter, for example, may require a curfew or scheduled group time; questions perceived as intrusive during an intake for Head Start might be required by government agencies; and a formulaic array of services may be the delivery system design that permits service to the greatest number of clients. These results, therefore, should not be interpreted as a systematic critique of community programs, and should be seen in the context of the positive comments that a number of informants communicated. Furthermore, it should be noted that our study informants should not be seen as passive recipients of the services they discuss; rather, there is more likely a complex interaction between clients and organizations, and one's degree of personal empowerment likely plays a significant role in this interaction.

Our study has a number of limitations. All informants spoke English, and all had the ability to access the services from which they were recruited. We cannot comment, therefore, on non-English speakers or populations who do not avail themselves of any social services. As with all qualitative research, themes are the product of a discussion between unique individuals; and although no systematic differences were discernable between our interviewers, it is possible that different interviewers would have generated different results. Furthermore, although our unexpected findings emerged from contextual questions, common to both sets of interviews – and our results held when we restricted the analysis to the Boston data only – it is possible that the original purposes of studies biased our findings on community resources. Although we continued to conduct interviews until thematic saturation was achieved in the Boston cohort, it is still possible that other, important themes remain undiscovered. Lastly, an inherent limitation of qualitative research is that it cannot estimate prevalence; therefore, we can make no comment on the frequency with which these perceptions are held or whether they are generalizable to other locales.

Because one important function of qualitative research is to generate hypotheses for further study (34), we offer such hypotheses as our study conclusions. It is known from previous research that a significant proportion of families referred to community-based services never receive them (35, 36) and that many potentially valuable services are undersubscribed in some parts of the country. Even when appropriate referrals are made, scarcity of resources is sometimes posited as a reason for non-receipt of services. It may be, however, that perceived disadvantages to engaging with community resources may create additional barriers to engagement. An important topic of future research, therefore, would be to assess the prevalence of the perceptions uncovered in our study and whether such perceptions indeed create barriers to engagement. If the do, discerning whether these perceptions come from direct experiences with community agencies or from larger contextual issues such as racism or the chronic demoralization that comes with poverty would be important. We further hypothesize that a systematic understanding of parents’ perceptions of community-based resources is important to maximizing their client-centeredness; and this that type of research may ultimately be important to the provision of quality, client-centered healthcare.

Figure.

Themes regarding the unintended consequences of engaging with community resources, depicted within the context of experiencing life as a series of unfriendly negotiations

Acknowledgement

We thank Howard Bauchner, MD and Barry Zuckerman, MD for their thoughtful review of the manuscript. We thank Samere Reid for conducting a portion of the interviews and participating in the data analysis. We thank Lance Laird, Th.D. for sharing his insight on qualitative methodology. We thank the Joel and Barbara Alpert Children of the City Endowment for supporting this work. Dr. Silverstein is also supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH074079) and the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):579–612. iv–v. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Chronic Illness Care . The Chronic Care Model. Seattle, WA: 2008. [August 12, 2008]. URL: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=The_MacColl_Institute&s=93. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks-Gunn J, McCarton CM, Casey PH, McCormick MC, Bauer CR, Bernbaum JC, et al. Early intervention in low-birth-weight premature infants. Results through age 5 years from the Infant Health and Development Program. JAMA. 1994;272(16):1257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarton CM, Brooks-Gunn J, Wallace IF, Bauer CR, Bennett FC, Bernbaum JC, et al. Results at age 8 years of early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants. The Infant Health and Development Program. JAMA. 1997;277(2):126–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Buka SL, Goldman J, Yu J, Salganik M, et al. Early intervention in low birth weight premature infants: results at 18 years of age for the Infant Health and Development Program. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):771–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckenrode J, Ganzel B, Henderson CR, Jr., Smith E, Olds DL, Powers J, et al. Preventing child abuse and neglect with a program of nurse home visitation: the limiting effects of domestic violence. JAMA. 2000;284(11):1385–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.11.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olds D, Henderson CR, Jr., Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, et al. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children's criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(14):1238–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr., Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):637–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Ou SR, Robertson DL, Mersky JP, Topitzes JW, et al. Effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being: a 19-year follow-up of low-income families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(8):730–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Robertson DL, Mann EA. Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest: A 15-year follow-up of low-income children in public schools. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2339–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuckerman B, Sandel M, Smith L, Lawton E. Why pediatricians need lawyers to keep children healthy. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):224–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerman B, Halfon N. School readiness: an idea whose time has arrived. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 Pt 1):1433–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagan JF, Shaw J, Duncan P, editors. Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervisions of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd ed American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngui EM, Flores G. Satisfaction with care and ease of using health care services among parents of children with special health care needs: the roles of race/ethnicity, insurance, language, and adequacy of family-centered care. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1184–96. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dempsey AF, Zimet GD, Davis RL, Koutsky L. Factors that are associated with parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines: a randomized intervention study of written information about HPV. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1486–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paxton RD, Byington CL. An examination of the unintended consequences of the rule-out sepsis evaluation: a parental perspective. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2001;40(2):71–7. doi: 10.1177/000992280104000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 3rd ed. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estabrooks CA, Field PA, Morse JM. Aggregating Qualitative Findings: An Approach to Theory Development. Qual Health Res. 1994;4(4):503–511. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flemming K. The synthesis of qualitative research and evidence-based nursing. Evid Based Nurs. 2007;10(3):68–71. doi: 10.1136/ebn.10.3.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Focus of Qualitative Methods - Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Research in Nursing and Health. 1998;20(4):365–371. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199708)20:4<365::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman D. Interpreting Qualitative Data. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ, for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working G Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXIII. Qualitative Research in Health Care B. What Are the Results and How Do They Help Me Care for My Patients? JAMA. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ, for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working G Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXIII. Qualitative Research in Health Care A. Are the Results of the Study Valid? JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Applewhite S. Homeless Veterans: Perspectives on Social Service Use. Social Work. 1997;42(1):19–30. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bent-Goodley T. Perceptions of Domestic Violence: A Dialogue with African American Women. Health and Social Work. 2004;29(4):307–316. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darbyshire P, Muir-Cochrane E, Fereday J, Jureidini J, Drummond A. Engagement with Health and Social Services: Perceptions of Homeless Young People with Mental Health Problems. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2006;14(6):5530562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Institute of Medicine; Washington, D.C.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaller D. Patient-Centered Care: What does it Take? Commonwealth Fund; New York City: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry LL, Seiders K, Wilder SS. Innovations in access to care: a patient-centered approach. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(7):568–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):953–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2848–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Co JP, Perrin JM. Qualitative Research and Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(3):129–130. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2005)5[129:QRAAP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverstein M, Mack C, Reavis N, Koepsell TD, Gross GS, Grossman DC. Effect of a clinic-based referral system to head start: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(8):968–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Needlman R, Kelly S, Higgins J, Sofranko K, Drotar D. Impact of Screening for Maternal Depression in a Pediatric Clinic: an Exploratory Study. Ambulatory Child Health. 1999;5:61–71. [Google Scholar]