Abstract

Objective

The current study tested whether daily interpersonal events predicted fatigue from one day to the next among female chronic pain patients.

Design

Self-reported fatigue, daily events, pain, sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and functional health across 30 days were assessed in women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA: n = 89), Osteoarthritis (OA: n = 76), and Fibromyalgia syndrome (FM: n = 90).

Main Outcome Measures

Self-report fatigue measured on a zero to one hundred scale and fatigue affect from PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1994).

Results

Multi-level analyses showed that both higher average levels of and daily increases in negative events predicted more fatigue, whereas daily increases in positive events predicted less fatigue. Across all pain conditions, increases in negative events continued to predict higher fatigue on the following day. Moreover, for participants with FM or RA, increases in positive events also predicted increased fatigue the following day. Daily increases in fatigue, in turn, predicted poorer functional health on both the same day and the next day.

Conclusion

These results indicate that both on average and on a daily basis, interpersonal events influence levels of fatigue beyond common physical and psychological correlates of chronic pain and highlight differences between chronic pain groups.

Keywords: Fatigue, interpersonal events, chronic pain conditions

Symptoms of fatigue are common to nearly every major chronic illness (Craig et al., 2003; Evans & Wickstrom, 1999; Franck et al., 1999) and are especially prevalent in pain disorders such as Fibromyalgia syndrome (FM), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and osteoarthritis (OA; e.g., Fishbain et al., 2003; Wolfe, 1999). Wolfe and colleagues (1996) found that clinically significant fatigue was reported by more than 41% of patients with OA or RA, and by 76% of patients with FM. In these conditions, fatigue has been linked with other clinical signs of chronic illness including pain (see Fishbain et al., 2003, p. for a review) and poor sleep (Belza, 1995; Nicassio, Moxham, Schuman, & Gevirtz, 2002; Stone, Broderick, Porter, & Kaell, 1997). In this paper, we take a different approach; we examine predictors of fatigue not directly associated with chronic illness: the everyday occurrence of positive and negative interpersonal experiences.

Although most investigators have treated fatigue as a sign of a physical disease process, it is hard to ignore its potential linkages to psychological and social aspects of health and illness. Fatigue or “low energy” continues to be a major criterion for a diagnosis of depression or dysthymia (e.g., , Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, 2000). Moreover, fatigue and depression arise as cofactors not only among those with chronic medical problems, but also healthy individuals (Belza, 1995; Chen, 1986; Kurtze & Svebak, 2001; Lavidor, Weller, & Babkoff, 2002; Nicassio, Moxham, Schuman, & Gevirtz, 2002). Consideration of fatigue as an indicator of affective disturbance as well as poor physical health, invites further exploration of the role of psychosocial factors that have been shown to influence emotional states.

The assessment of everyday life events offers a well-established (Zautra, Affleck, Davis, Tennen, & Fasman, 2005)method of examining the ebb and flow of psychosocial stressors and benefits that may influence fatigue. Little is known about relations between fatigue and the everyday interpersonal events, and for those coping with the ongoing demands of chronic pain. Social stressors may further strain the adaptive capacity of pain patients, increasing vulnerability to fatigue (Zautra et al., 2005). Further, fatigue may be thought to arise not only because of the costs of adaptation from chronic stress and depression, but also because of a failure of energy restoration from activities that promote positive well-being (Zautra, 2003). Thus, there may be a unique role of psychosocial deficits in the experience of fatigue over an above the contribution of disease processes. The role of positive social events in experiences of fatigue has not been studied, but from a biopsychosocial perspective (Engle, 1977), we may surmise that such events are likely to increase vitality and decrease fatigue as part of their more general influence in promoting well-being. Positive events have been related to increase in positive affect (Zautra, Affleck, Tennen, Reich, & Davis, 2005). In a prior paper, we found positive affect to be a strong negative association with fatigue (Zautra, Fasman, Parish, & Davis, 2007)

With repeated daily records of events and fatigue, it is possible to estimate the influence of both state and trait factors associated with fatigue. Historically, most studies have relied at most on two repeated measures of fatigue, and studied only one illness at a time, a strategy that does not permit examination of differences both between groups and within individuals over time in manifestations of fatigue. Measurement processes capable of repeatedly examining ongoing experiences, such as daily diaries (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003), help correct for recall biases stemming from retrospective reports, and with sufficient observations, can provide a means of obtaining reliable estimates of variance partitioned into two sources: between-persons and within-persons over time (Tennen & Affleck, 1996). Indeed, daily variation in fatigue has not yet been examined in detail, and the findings have the potential to expand the knowledge base regarding psychosocial predictors and properties of fatigue, as well as the extent to which these components vary within and between individuals with different diagnoses.

By taking into consideration the established correlates of depression, pain and sleep quality, we first sought to examine the additional influence of both positive and negative daily interpersonal events on fatigue. We then tested whether the relations between daily events and fatigue varied depending on chronic pain condition. Further, we tested whether the event-fatigue relations held true for next day's fatigue to probe the temporal order of these relationships. Finally, we examined whether fatigue itself predicted a health outcome such as diminished physical functioning as a separate analyses exploring outcomes of fatigue. In an effort to probe the reproducibility of the findings to multiple measures, we employed two indicators of fatigue; the primary which is a zero to one hundred rating used in prior studies and as a secondary measures, we included the five item fatigue affect scale taken from the PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1994) to see if similar findings would result.

Method

Participants

To best answer our study questions, data from two similar large studies were combined for analyses. The first study included female patients with RA, and the second included female patients with OA and FM.

Study 1

Two hundred and fifty-six participants between the ages of 21 and 79 years (M = 52.3) were recruited from physician's offices, advertisements, senior citizen groups, and mailings to members of the Arthritis Foundation as well as referrals from VA hospital rheumatologists. For inclusion in the study, participants were required to be women between 21 and 80 years of age, have a physician-confirmed diagnosis of RA, the absence of Lupus, and not be currently taking any cyclical estrogen replacement therapies. RA patients who reported to having OA (5 from physician confirmation of OA and RA) were included in the current analyses but seven RA patients who also reported having FM were excluded. Meeting these criteria were 124 participants. To further help match the pain criteria in Study 2, only 97 patients who reported pain greater or equal to 20 on a 0−100 scale on two or more days of their 30 diaries were included. Additionally, only participants whom had bilateral tenderness or swelling determined by a rheumatologist examination as part of a separate laboratory study on the sample were included resulting in 90 participants. One participant did not complete at least 10 days of diaries resulting in a total of 89 participants included in analyses.

Study 2

Two hundred sixty women between the ages and 38 and 72 (mean = 57.2, OA = 59.1, FM = 55.6) were recruited in a manner similar to that used for Study 1, with the exception that no participants were referred through rheumatologists at the VA. Participants were included in the present study if they met the following criteria: Had a physician confirmed diagnosis of OA or FM, no other autoimmune disorders, a pain rating above 20 on a 0−100 scale, and were not involved in litigation regarding their condition. In addition, participants with only OA could not have any other disease that could mimic the symptoms of FM and needed to report subjective worsening of their disease to an extent comparable to those patients with FM (i.e., pain rating greater than 40 in the last month). These remaining 213 participants were placed into FM or OA groups based on their own endorsement together with the physician's confirmation of the diagnosis. The OA group was comprised of individuals with a diagnosis of OA only, whereas the FM group was comprised of individuals with either FM only, or both FM and OA. Further, to address the potential problem of objective diagnosis of FM by different physicians, we supplemented the physician confirmations of diagnosis with data collected in the diary to assure distinct FM and OA groups. Only those FM patients who reported soft-tissue pain in four quadrants on at least one day out of 30 daily diaries were included in the current analyses. Similarly, only those OA participants who never reported soft-tissue pain in all four quadrants during the 30 days in their daily diary were included. These additional criteria led to exclusion of 44 participants (27 FM, 17 OA). An additional 3 (1 OA, 2 FM) participants were not included in analyses because they did not complete the minimum 10 days of diaries resulting in 76 OA and 90 FM participants

Procedure

Study 1

After being screened into the study, participants returned an informed consent form by mail along with documents authorizing study personnel to contact their doctors to confirm their diagnosis of RA. After confirmation of diagnosis, participants were sent and returned by mail an initial packet of questionnaires containing demographic variables and personality measures, including depression. After completing these questionnaires, participants were sent a packet of 30 paper diary questionnaires and 30 postage paid envelopes. Before beginning the diaries, participants were phoned by a research assistant and given instructions to fill out the diaries one half hour before bedtime each day. To insure compliance in completing the diaries on a daily basis, participants were instructed to place the completed diary from previous night in the prepaid envelope in the mail each morning. Postmark verification substantiated compliance with instructions and participants were reminded and given feedback by phone for missed diaries. Monetary compensation was based on satisfactory completion of the diary portion of the study. Overall, completion rate of the diaries was 94% for 27 out of 30 days. Among other questions, the daily diary contained measures of fatigue, positive and negative affect, daily pain, sleep disturbance and interpersonal small life events. Following completion of the diaries, participants were mailed another packet of questionnaires containing measures of sleep quality and depression.

Study 2

Procedures for Study 2 were generally similar to those employed in Study 1, but varied in the following ways: After completing the initial packet of measures, participants were asked to come into the lab to be trained to use a computerized version of the daily diary by a research assistant. Compliance in filling out the diary on a daily basis was ensured through built in date monitoring arguments within the software, yielding an overall 92% completion rate (90% for OA and 92% for FM). Further, we conducted a One-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc comparison to show no differences in completion rates between the three groups all p values > .29. After completing the diary phase, an in-home visit was scheduled where the participants were interviewed regarding sleep disturbance and asked to fill out the depression measure on the computer. At the end of the visit, the research assistant collected the computer, and compensated participants for the time spent for the visit and satisfactory completion of the diary.

Measures

The following measures were identical across studies sampled:

Fatigue

Daily fatigue was assessed by asking the participant: “What number between 0 and 100 best describes your average level of fatigue today? A zero (0) would mean ‘No fatigue’ and a one hundred (100) would mean ‘Fatigue as bad as it can be.’” (Jensen, Karoly, & Braver, 1986). Day to day test-retest reliabilities were computed, yielding a correlation of .64 for both studies combined (RA = .67, OA = .60, FM = .45). Correlation for average fatigue for the first fifteen days to the last fifteen days of diaries was .94 (RA = 93, OA = .96, FM = .85). In addition, the validity of this single item fatigue scale was probed by taking its correlates with other similar measures. Fatigue strongly negatively correlated with the SF-36 Vitality subscale (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992): all participants r = −.60 (RA = −.59, OA = −.46, FM = −.48; all p values <.01).

Fatigue Affect

Daily fatigue affect was measured by averaging the scores from the 4 item fatigue subscale from the PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1994). Between-person reliabilities were computed by first aggregating each participant's items across all days. Cronbach's alpha was .95 (RA = .93, OA = .92, FM = .95). Within-person reliability estimates were computed by first transforming item scores into z-scores within each participant. Within-person Cronbach's alpha was .85 (RA = .85, OA = .84, FM = .85). Daily scores of fatigue correlated strongly with daily Fatigue Affect: all participants r = .61 (RA = .57, OA = .57, FM = .61; all p values < .01).

Positive and Negative Interpersonal events

Interpersonal events were measured using an abridged version of the Inventory of Small Life Events (ISLE) for older adults (Zautra, Guarnaccia, & Reich, 1988; Zautra, Schultz, & Reich, 2000). Participants were asked if any of 30 positive or 29 negative interpersonal events occurred that day. Sum scores for both positive and negative events were computed for each day. Cronbach's alpha was not computed for these scores because the items are designed to measure non-overlapping interpersonal events. To measure stability, test-retest reliabilities were computed across days to yield an average day-to-day correlation of .57 for positive interpersonal events (RA = .51, OA =. 59, FM = .58) and .42 for negative events (RA = .39, OA = .42, FM = .46). As expected, positive events showed greater daily stability than negative events (Zautra et al., 1995). Correlations of average values from first 15 days to the last fifteen days were .93 for positive events (RA = .94, OA = .92, FM = .95) and .90 (RA = .88, OA = .92, FM = .90) for negative events.

Depression

Pro-rated raw scores from the Hamilton Depression Inventory –Short Form (Reynolds & Kobak, 1995) were used to assess levels of depression. Cronbach's alpha on the 9-item scale was .84 for both studies combined (RA = .72, OA = .89, FM = .87).

Sleep Disturbance

The Pittsburgh Sleep Inventory (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) was administered in both studies after the diary phase. Cronbach's alpha overall was .77 (RA = .76, OA = .78, FM = .67).

Pain

Daily pain was measured in each diary with the standard instruction for a numerical rating scale (Jensen, Karoly, & Braver, 1986; Zautra, Smith, Affleck, & Tennen, 2001), “Please choose a number between 0 and 100 that best describes the average level of pain you have experienced today due to your pain condition (‘Rheumatoid arthritis’ in Study 1 and “Fibromyalgia or Osteoarthritis’ in Study 2). A zero (0) would mean ‘no pain’ and a one hundred (100) would mean ‘pain as bad as it can be.’” Test-retest reliabilities were computed across days to yield a day-to-day correlation of .73 for both studies combined (RA = .75, OA = .65, FM = .53)

Physical functioning

Four items from the SF-36 Role limitation due to physical health, adapted to refer to the participants pain condition, were measured in each diary (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). For example, participants were asked, “Today, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular activities as a result of your condition?” They then rated items such as “Did you accomplish less than you would like?” on a scale of one to three where one meant “no”, two meant “yes, slightly”, and three meant “yes, very much”. The four items were reverse scored and summed such that a higher score meant better physical functioning. Between-person reliabilities were computed by first aggregating each person's items across all days with a resulting Cronbach's alpha of .96 (RA = .97, OA = 96, FM = .96). Within-person reliability estimates were computed by transforming item scores into z-scores within each participant yielding an alpha of .74 (RA = .76, OA = .73, FM = .74).

Analytic strategy

Data sets from both studies were combined and structured in a multilevel format, such that there were up to 30 observations for the each of the 255 participants. Multilevel analyses were conducted using the SAS PROC MIXED software (Littell, 1996) to examine both between and within-person predictors in daily fatigue and fatigue affect. Between-person predictors included depression, sleep disturbance, and aggregate measures of the three measures from the diary. Average scores across the 30 days constituted the between person measures of pain, positive interpersonal events, and negative interpersonal events. To create within-person measures of pain and events, the average score across 30 days was subtracted from each daily score, providing a deviation score. Predictors of fatigue were tested as random effects and specifications for the multilevel models were selected following Singer (1998) to identify the best fitting model of the variances and covariances of the variables examined. Because of the autocorrelational nature of dependent variables in repeated measures analyses, prior day fatigue was used as a control when predicting same-day fatigue. Likewise, same-day fatigue was used as a control when predicting next-day fatigue. Daily changes in pain were found to vary randomly and therefore was included in the random effects model.

We proceeded to analyze the data in the following order: Our first equations predicting fatigue looked at both between-person predictors, such as depression, sleep disturbance, and average scores of interpersonal events and pain, as well and within-person predictors, such as daily measures of pain, interpersonal events. Next, we tested differences between diagnostic groups by adding contrast-coded variables, and then probed for interactions within each pain group. To illustrate, the basic equation was specified for daily fatigue:

β0 yields an estimate of the intercept for joint pain, β1 is used here to stand in for control variables including depression, sleep disturbance, pain, and prior day's fatigue. Coefficients β2−6 provide slope estimates of main effects of predictor variables. In this equation, the slope β2 designates overall group differences between pain groups, β3−4 provide the slope coefficients for main effects due to average between-person interpersonal events and pain, β5 tests for difference between pain groups. Slopes β10−11 test for differences between pain groups on daily changes in pain and interpersonal events.

To probe for relationships over time, we created lagged scores of fatigue to test whether the same model would predict fatigue the next day. Lastly, we looked at the outcomes of fatigue, to first confirm the direction of our model and to examine the impact of fatigue on daily functioning. These analyses tested fatigue as a predictor of physical functioning on the same day and on the next day. These analyses again used the specifications for model fit outlined in (Singer, 1998). Unlike the earlier equations predicting fatigue, a standard (AR) process was used to control for day-to-day autocorrelational effects. In this case, we tested whether the relation of fatigue to physical functioning extended to the next day, rather than the direct effects of physical functioning from one day to the next.

Results (these findings are the same as reported in previous study)

Table 1 displays means and standard deviations of all measures for each of the three diagnostic groups. One way ANOVA's yielded the following differences between groups. The OA group was an average of 5.9 years older than the other two groups. The FM group reported more pain than the OA group (p < .05), which reported more pain than the RA group (p < .05). The FM group also reported more sleep disturbance, more depression, and more fatigue and fatigue affect and lower physical functioning than both the Ra and OA groups (p < .05). It is important to note that the groups were not different in the frequency of their reports of interpersonal events.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographic and study variables.

| |

RA (n = 89) |

OA (n = 76) |

FM (n = 90) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

| Age |

52.33(12.69)a |

59.60(8.09)b |

55.17(8.9)a |

| Income | 28.65% < $25k | 17.6% < $25k | 37.2% < $25k |

| |

Mean 30−40k |

Mean 30−40k |

Mean 25−30k |

| Education: Highest level | 13.3 % H.S. | 11.9 % H.S. | 14.9 % H.S. |

| Completed |

84.0 % College |

85.1 % College |

83.8 % College |

| Sleep Disturbance |

8.43(4.11)a |

8.22(4.03)a |

12.25(3.51)b |

| Depression |

6.12(4.13)a |

5.92(4.38)a |

10.31(5.58)b |

| Pain (0−100) |

35.53(17.26)a |

43.62(17.81)b |

62.70(12.02)c |

| Fatigue (0−100) |

33.53(17.31)a |

37.43(19.43)a |

55.81(12.93)b |

| Fatigue Affect |

2.10(0.71)a |

1.86(0.63)a |

2.56(0.80)b |

| Average Negative Events |

0.93(0.83)a |

0.65(0.76)a |

0.87(0.91)a |

| Average Positive Events |

5.15(2.09)a |

5.66(2.45)a |

5.98(2.77)a |

| Average Physical Functioning | 5.88(1.33)a | 6.22(1.23)a | 5.08(1.01)b |

Note. Different superscripts within a row represent significantly different groups in Tukey HSD Post Hoc comparisons at p <.05.

We began developing a model to predict fatigue by examining common predictors of fatigue such as pain, sleep disturbance, and depression. As expected, prior day's fatigue, average pain, changes in pain, and depression were significant predictors of daily fatigue. To test for differences between pain groups, contrast coded variables were added to the model. Although t-tests showed the FM group reported higher fatigue on average than the other two groups, once pain was entered into the equation, the diagnosis of FM was no longer a significant predictor of fatigue. Moreover, there were no other significant differences between any of the pain groups in predictors of fatigue. Average between-person occurrences of positive and negative events were next added to the model. Participants who reported more negative events on average also reported more fatigue (t = 2.91, p < .01), whereas those who reported more positive events on average reported marginally less fatigue (t =−1.77, p = .07).

Our next step was to explore the relation of daily occurrences of positive and negative events to fatigue, and to test for diagnostic group differences by including interaction terms. When added to the model, both daily change in positive events (t =−5.69 p < .01) and, to a lesser extent, negative events (t =2.00, p <. 05) predicted fatigue. Because pain was also a significant predictor in this equation and because the FM group had higher pain overall, we probed for daily pain by diagnostic group interactions, and found a significant pain by FM diagnosis effect (t =3.07 p <.01). Figure 1a plots the relation between pain an fatigue for each pain group by using high/low median splits on pain scores, and illustrates that the FM group was more fatigued than the other groups on days when their pain was greater. The role of diagnostic group as a moderator of other daily change scores was tested by including additional interaction terms but only those found to be significant are reported in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Interaction of pain by group on fatigue.

Table 2.

Depression, sleep disturbance, pain, and interpersonal events in the prediction of fatigue and next-day fatigue.

| Random Effects | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | Next-day fatigue | |||||||||

| Covariance Parameter Estimates | β | SE | Z | p | β | SE | Z | p | ||

| Intercept | 91.92 | 9.39 | 9.78 | < .01 | 81.32 | 8.78 | 9.26 | <.01 | ||

| Δ Pain | 0.06 | 0.008 | 7.00 | < .01 | 0.02 | 0.005 | 4.46 | <.01 | ||

| Residual | 230.17 | 4.02 | 57.27 | < .01 | 281.02 | 4.89 | 57.38 | <.01 | ||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||||||

| Fatigue | Next-day fatigue | |||||||||

| Predictor Variables | β | SE | DF | t | p | β | SE | DF | t | p |

| Control Variables | ||||||||||

| Depression | 0.45 | 0.16 | 249 | 2.83 | <.01 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 249 | 2.76 | <.01 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 0.29 | 0.18 | 249 | 1.63 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.17 | 249 | 1.76 | 0.08 |

| Pain | 0.55 | 0.04 | 249 | 14.62 | <.01 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 249 | 14.61 | <.01 |

| Prior Day's Fatigue | 0.15 | 0.01 | 6798 | 14.12 | <.01 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 6797 | 15.16 | <.01 |

| Level 2 | ||||||||||

| Pos. Events | −0.48 | 0.27 | 249 | −1.77 | 0.07 | −0.46 | 0.26 | 249 | −1.79 | 0.07 |

| Neg. Events | 2.36 | 0.81 | 249 | 2.91 | <.01 | 2.18 | 0.78 | 249 | 2.81 | <.01 |

| OA | −0.38 | 1.43 | 248 | −0.27 | 0.78 | −0.73 | 1.36 | 248 | −0.53 | 0.59 |

| RA | −1.24 | 1.51 | 248 | −0.82 | 0.41 | −0.99 | 1.44 | 248 | −0.69 | 0.49 |

| FM | 2.08 | 1.68 | 248 | 1.24 | 0.22 | 2.26 | 1.6 | 248 | 1.41 | 0.16 |

| Level 1 | ||||||||||

| Δ Pos. Events | −0.45 | 0.08 | 6798 | −5.69 | <.01 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 6797 | 2.32 | <.05 |

| Δ Neg. Events | 0.34 | 0.17 | 6798 | 2.00 | <.05 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 6797 | 3.23 | <.05 |

| Δ Pain | 0.41 | 0.02 | 6798 | 19.87 | <.01 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 6797 | 4.23 | < .01 |

| Level 1 × Group | ||||||||||

| Pain × FM | 0.1299 | 0.04 | 6797 | 3.07 | <.01 | −0.005 | 0.04 | 6796 | 1.41 | 0.16 |

| Pos. Events × OA | 0.07 | 0.18 | 6797 | 0.43 | 0.66 | −0.6290 | 0.19 | 6796 | −3.32 | <.01 |

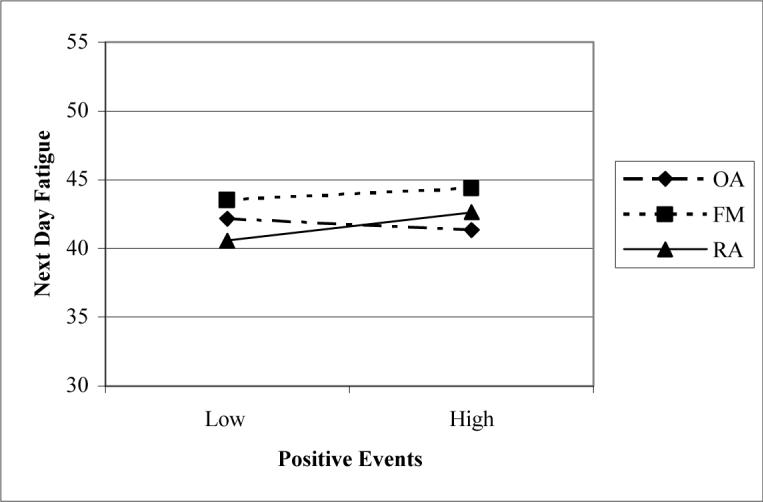

To examine the predictive relationship of events and other predictors on fatigue over time, we used the same prediction equation for same-day fatigue to predict next-day fatigue. In this analysis, we continued to find that between-person measures of average pain, depression and average negative events significantly predicting next-day fatigue. Average positive events also continued to have a similar albeit marginal relationship with lower next-day fatigue. More importantly, daily changes in negative events continued to have a positive relationship when predicting next-day fatigue (t =3.23, p < .05). Positive events, surprisingly, showed a reversal in effects from one day to the next. While positive events showed a negative relationship to fatigue on the same-day, they had a significant positive relationship to fatigue the next day (t =2.32 p < .05). To further explore this finding, we included daily positive events by diagnostic group interactions in the model. The FM group by pain interaction was no longer significant for next-day fatigue, but a significant interaction of positive events by the OA group emerged (t =−3.32 p < .01). This interaction, illustrated in figure 2a, indicates that for the OA group, when positive events are high, next-day fatigue reports decreases; in contrast, for the FM and RA groups, increases in positive events are followed by increases in next-day fatigue.

Figure 2.

Interaction of Positive Events by group on next-day fatigue.

We next repeated our series of analyses, this time evaluating fatigue affect (rather than fatigue) as the outcome. Findings were very similar for prediction of same-day and next-day fatigue affect, with only the following differences: 1) Both between and within-person levels of pain were weaker predictors of fatigue affect versus fatigue; 2) Sleep disturbance was a significant predictor of fatigue affect (t = 3.3, p < .01) even when pain and depression were included in the equation. In contrast, sleep disturbance was not a significant predictor in the full model for fatigue; and 3) A main effect for the OA contrast variable emerged in the analyses for fatigued affect, indicating less fatigue affect for the OA group than the other two groups (t =−2.17, p < .05).

Lastly, daily physical functioning was examined as a potentially important health consequence of fatigue. Table 3 depicts findings generated from two equations testing whether fatigue predicted physical functioning on the same day and on the following day. Appropriate covariates were tested in these equations (i.e., depression, pain and sleep disturbance) and those found to be non-significant were dropped from the final equations. Both higher average pain levels and daily increases in pain were significant predictors of poorer physical functioning. While average (between-person) fatigue was not a significant predictor, daily increases in fatigue predicted poorer physical functioning on the same day (t =−13.80, p < .01). More importantly, daily increases in fatigue marginally predicted poorer next-day physical functioning (t =−2.60, p = .057).

Table 3.

Pain and fatigue in the prediction of same-day and next-day physical functioning.

| Random Effects | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functioning | Next-day Functioning | |||||||||

| Covariance Parameter Estimates | β | SE | Z | p | β | SE | Z | p | ||

| Intercept | 1.122 | 1.065 | 10.53 | <.01 | 1.080 | 0.104 | 10.39 | <.01 | ||

| Δ Pain | 0.0005 | 0.00007 | 7.16 | <.01 | 0.0001 | 0.00002 | 4.16 | <.01 | ||

| AR(1) | 0.145 | 0.014 | 10.10 | <.01 | 0.179 | 0.016 | 11.30 | <.01 | ||

| Residual | 0.993 | 0.019 | 52.37 | <.01 | 1.206 | 0.024 | 49.78 | <.01 | ||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||||||

| Functioning | Next-day Functioning | |||||||||

| Predictor Variables | β | SE | DF | t | p | β | SE | DF | t | p |

| Between-person Variables | ||||||||||

| Average Pain | −0.029 | 0.005 | 248 | −5.45 | <.01 | −0.031 | 0.005 | 248 | −5.82 | <.01 |

| Average Fatigue | −0.008 | 0.005 | 248 | −1.48 | 0.14 | −0.008 | 0.005 | 248 | −1.44 | .15 |

| Within-person Variables | ||||||||||

| Δ Pain | −0.018 | 0.002 | 6186 | −10.06 | <.01 | −0.003 | 0.001 | 5799 | −2.60 | <.01 |

| Δ Fatigue | −0.012 | 0.0008 | 6186 | −13.80 | <.01 | −0.002 | 0.0009 | 5799 | −1.90 | .057 |

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the role of psychosocial factors in daily reports of fatigue among chronic pain patients, and examined the contributions of features of the chronic illness itself. Pain, depression, and sleep disturbance, as well as contrasts between types of rheumatic conditions, were incorporated into the models when testing for the influence of everyday interpersonal experiences on fatigue. The evidence points clearly to an association between the occurrence of interpersonal events and fatigue, and between fatigue and physical functioning, an important measure of health. The results also reveal differences between diagnostic groups both in the level of fatigue and in the relations between interpersonal events and fatigue.

Our examination of the role of interpersonal events on fatigue and fatigue affect after controlling for covariates of sleep depression and pain, average between-person levels of both positive and negative interpersonal events related to daily levels of fatigue, showing that for those with more frequent negative events on average reported more fatigue and those with more frequent positive events on average reported marginally less fatigue. On a daily basis, negative events were related to higher levels of same-day fatigue, and this relationship remained when predicting next day fatigue scores. These findings are consistent with those found earlier on a Juvenile RA sample (Laura E. Schanberg, 2000). On the other hand, an increase in daily positive events was related to decreased levels of same-day fatigue. These findings expand on those found earlier by Ray and Jeffries (1995) showing that positive life events predict lower fatigue in those with chronic fatigue syndrome. Thus, a day high in negative events leaves individuals more fatigued on both the same and the following day, whereas positive events appear to be energy enhancing on the days in which they occur.

The relationship between positive interpersonal experiences and fatigue is a complex one, however. For those with FM and RA, increased positive events related to increases in next-day fatigue level. More importantly, these results suggest that individuals with FM or RA may experience an illness-related vulnerability associated with positive events. The initial boost in energy associated with positive events appears to be costly, leading to a deficit in energy on the following day. The carryover effects of positive events differ between individuals with FM and RA versus those with OA is interesting, given that the three groups are similarly reactive to positive events in terms of the same day's fatigue. Prior studies of fatigue have shown that those with FM and RA have a diminished ability to sustain positive mood in response to stress compared to those with OA (Zautra et al., 2005). Therefore, the inability to sustain energy from positive interpersonal events may derive from difficulties in the management of interpersonal relations for those with a certain type of chronic pain experience. Both FM and RA pain, unlike that of OA, is widespread and systemic (Arnett et al., 1988; Wolfe et al., 1990). The occurrence of positive events may lead to expectations of sustained social engagement that a person with chronic widespread pain may be unable to fulfill. Therefore responses from the person's social world that are challenging, perhaps even stressful for someone in chronic widespread pain.

Alternatively, diagnostic group differences in the ability to sustain energy may be at least partly accounted for by differences along a number of neurophysiological dimensions. Opioid (Charney, 2004; Van Houdenhove & Egle, 2004) and inflamatory (Kelley et al., 2003; Staud, 2004) responses to events, and neuronal regulation of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance (Craig & Sorkin, 2005) . These potential mechanisms are intriguing, but cannot be probed in the current study.

We found that the individuals with FM were higher not only in fatigue, but also in depression and pain compared to those with OA and RA in this sample, consistent with earlier observations (Weir et al., 2006). Our analyses further indicated that pain and depression mediated the relationship between the presence of FM and fatigue. These differences in affective disturbance could underlie the FM patients’ reports of more fatigue. Moreover, our findings indicate that those with FM experience comparatively more fatigue when in pain than those with RA and OA, suggesting that their higher reports of fatigue reflect a vulnerability to the affective dimension of the pain experience.

Different mechanisms may account for the rise in next day's fatigue following positive events for the RAs in our sample. Depression and stress have been associated with proinflammatory immune responses that promote disease activity and are linked to reports of fatigue in RA (Davis et al.). An existing deficit in sustainability of positive emotion, manifested as depression could be a co-factor underlying disease expression in RA via activation of autoimmune pathways.

Uncertainty in diagnostic classification between chronic pain groups may also have contributed to the differences we observed between groups. OA participants were screened out of the study if they had an accompanying diagnosis of FM, RA patients were recruited from a separate study for which FM was not exclusionary but excluded from our analyses. It is therefore possible that individuals categorized as having RA only also had FM and this might account for their similarity in terms of positive events such as next day fatigue. Future studies that provide for extensive confirmation of diagnoses and identification of “pure” groups would clarify these results. Our findings show the importance of making these distinctions among participants in chronic pain.

Although the pattern of findings was largely similar in analyses predicting fatigue versus fatigue affect, some minor differences emerged. Sleep disturbance was only a significant predictor of fatigue affect, even after other covariates were included in the equation. One possible explanation resides in the measures of fatigue themselves. The fatigue item asks participants to rate their fatigue on a 0 to 100 scale, whereas the fatigue affect scale includes items such as “sleepy”, “tired”, “sluggish”, and “drowsy”. The content of these specific affect items suggest they should strongly correlate with an individual's sleep disturbance. We also observed a stronger role for pain in predicting fatigue versus fatigue affect, possibly because both pain and fatigue ratings were made on a 0 to 100 rating scale.

Some potential limitations deserve comment. First, we assessed end-of-day reports of that day's experiences. More frequent within-day recordings of fatigue, pain, and interpersonal events and those that probe physiological changes may show similarities and differences between diagnostic groups responsible for the differences we have found here in self-reported fatigue. Second, we examined only chronic pain patients. As a result, we cannot generalize our findings to populations without a diagnosis of a chronic pain condition. Third, because we included only women as participants, we are unable to examine differences between sexes on pain-contingent and event-contingent fatigue. Fourth, because some of our FM sample also had OA, differences between FM and OA groups may have been somewhat muted. Although FM participants were asked if they could distinguish pain resulting from the two conditions, and reported that, their FM pain was more severe, the impact of fatigue may be different between FM patients with and without OA. However, including FM patients with OA provides a more conservative test of differences between groups and is more representative of the FM population. Lastly, other, more comprehensive measures of fatigue could provide greater specificity as to the nature of the fatigue experience for the different groups, and in so doing, reveal influential factors responsible for the findings (Hewlett, Hehir, & Kirwan, 2007).

Despite these limitations, using the daily diary approach in this research highlights the important role of interpersonal events as a determinant of fatigue providing support for a biopsychosocial framework for understanding these symptoms. By examining following day fatigue in relation to current day measures, we have shown the predictive nature of social events, both positive and negative, over and above common correlates of fatigue in those with chronic pain. Our findings also showed that fatigue exerted a negative, lingering effect on physical functioning from one day to the next regardless of pain condition. These findings suggest that fatigue preys equally on all the pain groups we studied, with consistent negative effects on clinically relevant indicators of functional health. Most fatigue interventions target those with cancer patients or chronic fatigue syndrome. Our results encourage the development of more cognitive-behavioral interventions to address fatigue associated with chronic pain. The current findings offer some points of emphasis and demarcation between conditions in the development of such interventions aimed at enhancing functioning and quality of life for those who experience fatigue as a part of their chronic pain condition.

Acknowledgements

Grant funding from the Arthritis Foundation and National Institute on Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases Grants R01 AR 046034 and R01 AR 041687 to the second author supported this research.

References

- Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belza BL. Comparison of self-reported fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis and controls. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(4):639–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):195–216. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MK. The epidemiology of self-perceived fatigue among adults. Prev Med. 1986;15(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD, Sorkin LS. Pain and Analgesia. 2005 http://psychology.unn.ac.uk/andrew/PY019/Pain%20and%.

- Craig TJ, Mende C, Hughes K, Kakumanu S, Lehman EB, Chinchilli V. The effect of topical nasal fluticasone on objective sleep testing and the symptoms of rhinitis, sleep, and daytime somnolence in perennial allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Younger J, Motivala SJ, Attrep J, Irwin MR. Chronic Stress and Regulation of Cellular Markers of Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Implications for Fatigue. submitted for publication. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Engle GL. The Need for a New Medical Model: A challenge for Biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–196. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EJ, Wickstrom B. Subjective fatigue and self-care in individuals with chronic illness. Medsurg Nurs. 1999;8(6):363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbain DA, Cole B, Cutler RB, Lewis J, Rosomoff HL, Fosomoff RS. Is pain fatiguing? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2003;4(1):51–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck LS, Johnson LM, Lee K, Hepner C, Lambert L, Passeri M, et al. Sleep disturbances in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics. 1999;104(5):e62. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.5.e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett S, Hehir M, Kirwan JR. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review of scales in use. Arthritis Care & Research. 2007;57(3):429–439. doi: 10.1002/art.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986;27(1):117–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KW, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Zhou JH, Shen WH, Johnson RW, et al. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtze N, Svebak S. Fatigue and patterns of pain in fibromyalgia: correlations with anxiety, depression and co-morbidity in a female county sample. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74(Pt 4):523–537. doi: 10.1348/000711201161163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura E, Schanberg MJSKSKMGJCLFJKGAHT. The relationship of daily mood and stressful events to symptoms in juvenile rheumatic disease. 2000;13:33–41. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)13:1<33::aid-art6>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavidor M, Weller A, Babkoff H. Multidimensional fatigue, somatic symptoms and depression. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7(1):67–75. doi: 10.1348/135910702169367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC. In: SAS system for mixed models. Littell Ramon C., Milliken George A., Stroup Walter W., Wolfinger Russell D., editors. SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, N.C.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nicassio PM, Moxham EG, Schuman CE, Gevirtz RN. The contribution of pain, reported sleep quality, and depressive symptoms to fatigue in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2002;100(3):271–279. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray C, Jefferies S, Weir WR. Life-events and the course of chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Med Psychol. 1995;68(Pt 4):323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1995.tb01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Kobak KA. Hamilton Depression Inventory: A Self-Report Version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Odessa: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to Fit Multilevel Models, Hierarchical Models, and Individual Growth Models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;23(4):323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Staud R. Fibromyalgia pain: do we know the source? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(2):157–163. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200403000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Broderick JE, Porter LS, Kaell AT. The experience of rheumatoid arthritis pain and fatigue: Examining momentary reports and correlates over one week. Arthritis Care & Research. 1997;10(3):185–193. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G. Daily processes in coping with chronic pain: Methods and analytic strategies. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications. John Wiley & Sons; Oxford, England: 1996. pp. 151–177. [Google Scholar]

- Van Houdenhove B, Egle UT. Fibromyalgia: a stress disorder? Piecing the biopsychosocial puzzle together. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(5):267–275. doi: 10.1159/000078843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF- 36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. University of Iowa; Iowa City: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weir PT, Harlan GA, Nkoy FL, Jones SS, Hegmann KT, Gren LH, et al. The incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a population-based retrospective cohort study based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006;12(3):124–128. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000221817.46231.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F. Determinants of WOMAC function, pain and stiffness scores: evidence for the role of low back pain, symptom counts, fatigue and depression in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(4):355–361. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(8):1407–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra A, Smith B, Affleck G, Tennen H. Examinations of chronic pain and affect relationships: Applications of a dynamic model of affect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(5):786–795. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ. Emotions, Stress, and Health. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Affleck G, Davis MC, Tennen H, Fasman R. Assessing the ebb and flow of everyday life with an accent on the positive. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Affleck GG, Tennen H, Reich JW, Davis MC. Dynamic Approaches to Emotions and Stress in Everyday Life: Bolger and Zuckerman Reloaded With Positive as Well as Negative Affects. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(6):1511–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Fasman R, Parish BP, Davis MC. Daily fatigue in women with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Pain. 2007;128(1−2):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Fasman R, Reich JW, Harakas P, Johnson LM, Olmsted ME, et al. Fibromyalgia: evidence for deficits in positive affect regulation. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):147–155. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146328.52009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Guarnaccia CA, Reich JW. Factor structure of mental health measures for older adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(4):514–519. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Marbach JJ, Raphael KG, Dohrenwend BP, Lennon MC, Kenny DA. The examination of myofascial face pain and its relationship to psychological distress among women. Health Psychology. 1995;14(3):223–231. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Schultz AS, Reich JW. The role of everyday events in depressive symptoms for older adults. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2000. [Google Scholar]