Abstract

Priapism is a pathological condition of penile erection that persists beyond, or is unrelated to, sexual stimulation. Pathologically and clinically, two subtypes are seen—the high flow (non‐ischaemic) variety and the low flow (ischaemic) priapism. The low flow type is more dangerous, as these patients are susceptible to greater complications and the long term recovery of erectile function is dependent on prompt and urgent intervention. Many of the causes of priapism are medical, including pharmacological agents, and as such, priapism should be considered as a medical and surgical emergency.

Keywords: priapism, urology

The term priapism was derived from the Greek god Priapus, son of Aphrodite. His father was Zeus, and it is written that when Hera, the wife of Zeus, heard of the pregnancy she cursed the child, such that, when the boy was born with oversized genitals, he was rejected by Aphrodite. Priapus was therefore brought up by shepherds who noticed that in his vicinity, flowers would bloom and animals would copulate furiously. He was thus made a god of fertility1 and his giant phallus was made a symbol of power.2 Priapism has been reported in the ancient papyrus of the Pharaonic Egypt and pescriptions for its treatment are found in Ebers Papyrus.3 The earliest record of priapism in modern literature was by Petraens in 1616, in an article entitled “Gonorrhoea, Satyriasis et Priapisme”4 and the first account of priapism appearing in the English literature was by Trife in 1845.5 Subsequently, there were isolated case reports of this mysterious illness and the various unsuccessful attempts at management. It was in 1914, that Frank Hinman published his seminal article on the pathophysiology of this unique condition, and his work was carried on by his son who postulated that venous stasis, combined with increased blood viscosity and ischaemia, played an important part in development.6 The first report of the high flow variant of priapism was by Burt et al in 1960, in a young man, which developed after a traumatic coitus.7 The concept of high arterial inflow and non‐ischaemic nature of this type of priapism was described by Hauri et al, based on the findings of penile arteriography and cavernosography.8 Like any other mysterious disease, priapism has been linked to many myths in the past. The more interesting of these include association with genitourinary infection, urinary retention, failed ejaculation, and psychosis.4,9

Epidemiology and aetiology

Priapism has an incidence of 1.5 per 100 000 and can occur in all age groups from newborn to elderly.10 Typically, there is a bimodal peak of incidence, between 5 and 10 years in children and 20 to 50 years in adults. Sickle cell disease is the commonest aetiology in childhood while pharmacological agents are responsible for most cases of priapism in adults. There are a wide variety of other causes though, and these are summarised in box 1.

Pathophysiology

The understanding of the pathophysiology of priapism has improved over the past few decades, primarily because of the lack of knowledge of normal erectile physiology. Anatomically, it involves the corpora cavernosa only, sparing the corpus spongiosum and the glans, although there are isolated case reports to the contrary.11 Priapism results from a derangement of the penile haemodynamics, affecting the arterial component or the veno‐occlusive mechanism. This mechanism explains the two types of pripaism—high flow and low flow types. High flow priapism commonly follows an episode of trauma to the perineum or the genitalia resulting in increased flow through the arteries.12 This leads to the formation of arteriocavernous shunts, resulting in increased arterial flow into the cavernous tissue. The veno‐occlusive mechanism is usually intact and the patients experience erections of a more elastic consistency. Tissue anoxia and ischaemia are characteristically absent, there is absence of pain, and there is less chance of future erectile dysfunction, in contrast with low flow priapism. In ischaemic priapism, there is an abnormality in the veno‐occlusive mechanism, resulting in venous stasis and accumulation of de‐oxygenated blood within the cavernous tissue. Oxygenation of the erectile tissues is compromised and risk of future erectile dysfunction secondary to ischaemia and subsequent fibrosis is high if not treated expeditiously. Sickle cell disease represents the classic clinical scenario for this, where anoxia produces further sickling of the red cells, increasing the sludge effect. Haematological dyscrasias, parenteral hyperalimentation, and haemodialysis can also produce blood hyperviscosity and precipitate similar episodes.12,13,14

Box 1 Aetiology of priapism

Idiopathic

Drugs

-

Anticoagulants

-

-

Heparin

-

-

Warfarin

-

-

-

Antihypertensives

-

-

Dihydralazine

-

-

Guanethidine

-

-

Labetalol

-

-

Nifedipine

-

-

Phenoxybenzamine

-

-

Prazosin

-

-

-

Antidepressants

-

-

Phenelzine

-

-

Trazadone

-

-

Hypnotics

-

-

Clozapine

-

-

Diazepam

-

-

-

Blockers

-

Recreational drugs

-

-

Cocaine

-

-

Ethanol

-

-

Marijuana

-

-

-

Drugs for intracavernous injection

-

-

Papaverine

-

-

Prostoglandin E1

-

-

Phenoxybenzamine

Sildenafil citrate62

Testosterone63

Haematological disorders

Sickle cell anaemia

Leukaemia

Multiple myeloma

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria

Thalassaemia

Thrombocythaemia

Henoch‐Schonlein purpura

Metabolic disorders

Amyloidosis

Fabry's disease

Gout

Diabetes

Nephrotic syndrome

Renal failure

Haemodialysis

Hyperlipedaemic total parenteral nutrition

Trauma

Tumours (primary or metastatic)

Neurological disorders

Variants of priapism

The finding that sympathetic nervous system plays an important part in normal detumescence and the activation of neural reflex mechanisms during erections suggest a possible pathogenic role for the nervous system in priapism.15,16 Therefore, in addition to the classic theories described above, a neuronal as well as dyregulatory basis to priapism has been proposed.17 Neurogenic priapism is seen in patients with spinal cord injury,18 cauda equina compression syndrome,19 and for centuries has been noticed in the victims of hanging.20

Stuttering priapism is the recurrent self limiting episodes, which characteristically last for less than three hours, and is commonly seen in sickle cell disease.21 Another interesting variant is the refractory priapism in which there is rapid arterial refilling after aspiration for an ischaemic priapism. In the absence of any significant trauma and demonstrable arteriocavernous fistula, these probably represent a non‐traumatic idiopathic subvariant of high flow priapism.22

Priapism of the clitoris, although much rarer than its male counterpart, has been reported sporadically in the literature. It is commonly associated with drugs like trazadone, citalopram, bromocriptine, olanzapine,23 and fluoxetine,24 pelvic malignancies, blood dyscrasias, or retroperitoneal fibrosis.25 Congenital neonatal priapism is also a recognised clinical entity. Although most cases are idiopathic, birth trauma resulting from forceps delivery, respiratory distress syndrome, umbilical artery catheterisation, polycythaemia, and congenital syphilis are other known causes.26,27 Most of the reported cases of congenital priapism have been successfully treated conservatively, although the erectile dysfunction in the adulthood has not been assessed.

Idiopathic priapism is used to classify those without a known cause and it is thought to be precipitated by a normal penile erection, sexual stimulation, or prolonged sexual activity. Interestingly, before the introduction of intracavernous injection of vasoactive drugs for erectile dysfunction in 1984, most patients did not have a known cause of priapism and a third of these were classified as idiopathic.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of priapism is clinical and self evident usually. Specific points in the history, physical examination, and investigations will allow the aetiology to be established (see box 1). The duration of erection will establish the overall prognosis of successful treatment, as prolonged ischaemia and acidosis can lead to corporeal fibrosis, erectile tissue scarring and, in extreme cases, penile necrosis.28 The degree of pain can help differentiate the painful low flow priapism from the high flow variety, which is usually painless. Further aspects in the history include history of priapism and its treatment, use of drugs that might have precipitated the episode, history of pelvic, genital or perineal trauma, especially a perineal straddle injury, and a history of sickle cell disease or other haematological abnormality.29 In young children with high flow priapism, perineal compression with the thumb will cause prompt detumescence, called Piesis sign,30 and this may be of use in confirming the diagnosis. Although Piesis sign is useful in paediatric patients, its usefulness in an adult is questioned.31 A thorough examination will also rule out any possible primary pathology, such as malignancy. Serum should be screened for haematological dyscrasias, as it may be the presenting clinical feature of underlying disease (see box 2). Urine toxicology may be performed if the patient has been suspected of consuming an excess dose of antidepressants, psychoactive drugs, and illegal drugs that cause priapism (see box 1). However, the most important investigation is an intracorporeal blood gas analysis, as this permits the differentiation between low flow and high flow priapism (table 1).

Table 1 Intracorporeal blood gas analysis of low and high flow priapism.

| PO2 (mm Hg) | PCO2 (mm Hg) | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low flow priapism | <30 | >60 | ⩽7.25 |

| High flow priapism | >30 | <60 | >7.25 |

Box 2 Case history of priapism as the first presenting feature of an underlying haematological disease

A 30 year old man presented with a painful and persistent erection lasting for seven hours. He was otherwise fit and well and with no medical problems. Urgent intracorporeal blood gas analysis showed findings consistent with low flow priapism. After aspiration of the corpora cavernosa, the priapism resolved. Urgent blood tests and follow up with haematology showed a diagnosis of leukaemia. To date, the priapism has not recurred and the patient has normal erectile function.

Recent evidence also suggests that glucopaenia is an important factor in determining the return of the tone of cavernous smooth muscle and could be an independent predictor of prognosis.32 In addition, Doppler study and duplex sonogram of the penis can show systolic and diastolic velocities of the cavernous arteries, and using waveform analysis, the cavernous artery inflow and the venous sinusoidal outflow can be calculated. Arteriography should only be considered in high flow priapism resistant to medical therapy. After defining the aberrant or injured vessel, a super‐selective embolisation of the affected artery can successfully treat this type of priapism.

Treatment

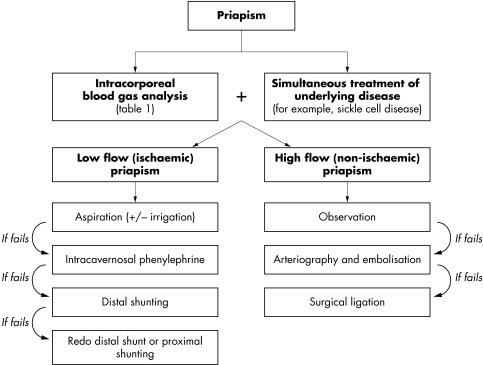

Understanding the physiology of erection has revolutionised the treatment of priapism, as previously the only treatments were local medical applications like cold lotions, belladonna and rhubarb, surgical remedies that included leeches, incision of the corpora, systemic therapy such as emetics and bloodletting, and sedation of sexual desire using drugs like potassium bromide.1 Although numerous therapeutic modalities have been described in the treatment of priapism, including application of leeches, anticoagulants, calomel, dextran, fibrinolytic agents, estrogens, ice water enemas, ice packs, hot packs, transrectal diathermy, venesection, spinal, caudal and general anaesthesia, the current management regimen is evidence based and according to the guidelines from the American Urological Association (fig 1).29

Figure 1 Algorithm describing the overall management of priapism.

Medical management of low flow priapism

Prompt intervention is warranted in all cases of low flow priapism to prevent long term erectile dysfunction. Any primary cause should be sought and corrected, if present. Aspiration with a non‐heparinised syringe into the base of one of the corpora cavernosa is the first line treatment, with a success rate around 30%.29 Aspiration can be combined with flushing the cavernosa with normal saline to clear the sludged blood. If this fails, instillation of a vasoconstrictive agent such as phenylephrine (100–200 mg/ml), repeated at five minute intervals until complete detumescence is achieved. This is found to be almost 100% effective, if done within 12 hours of onset.33 Interestingly, studies have shown that the success in detumnescence increases from 58%, with just intracavernosal sympathetomimetic therapy as compared with 77% when aspiration is combined with intracavernosal sympathetomimetic therapy.29

Five key references for further reading

Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol 2003;170:1318–25.

Winter CC. Cure of idiopathic priapism: new procedure for creating fistula between glans penis and corpora cavernosa. Urology 1976;8:389–91.

Hinman F Jr. Priapism: reasons for failure of therapy. J Urol 1960;83:420.

Eland IA, van der Lei J, Stricker BH, et al. Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology 2001;57:970.

Papadopoulos I, Kelami A. Priapus and priapism: from mythology to medicine. Urology 1988;32:385.

If priapism is of sickle cell aetiology, hydration, oxygenation, and systemic alkalinisation should be started to prevent further sickling. Corporeal aspiration and intracavernous α agonists should be given as soon as possible. Hypertransfusion is reserved for cases that fail the initial conservative treatment, because of the possible neurological side effects associated with this regimen.34 In special cases of priapism attributable to leukaemia, treatment with leukopheresis after failing aspiration may be necessary.35 In cases with recurrent episodes of priapism, intracavernous self administration of α agonists can be tried. Intracavernous self administration of metaraminol36 and adrenaline (epinephrine)37 has been tried with varying success. If sexual function is not a concern, antiandrogens or GnRH agonists can be tried, to prevent nocturnal penile tumescence and hence priapism.38

Surgical management of low flow priapism

This is used if conservative measures fail. The aim of surgical treatment is to provide a shunt between the corpus cavernosum and glans penis, corpus spongiosum or a vein so that the obstructed veno‐occlusive mechanism is bypassed. Shunts between the corpora cavernosa and glans, such as the Winter's procedure, wherein a biopsy needle is passed through the glans penis and into the corpora39,40,41 are reasonable initial procedures, although their success in maintaining detumescence has been questioned.42 In failed cases, a more definitive shunt between the cavernosum and spongiosum can be performed.43 The cavernosaphenous shunt described by Grayhack et al,44 and the cavernospongiosum shunt described by Quackles45 have been tried as shunt procedures, in resistant cases. The success rates for various surgical decompression procedures is around 75%.29

In a recent study, Rees et al evaluated the outcome of immediate insertion of penile prosthesis in patients presenting with priapism not responding to conventional treatment.46 It was found that there were no early complications with all the patients being satisfied with the end result, and most became sexually active. All patients maintained their penile length.

Medical management of high flow priapism

Non‐interventional management or observation has been recognised as a viable option in the treatment of non‐ischaemic priapism, as evidence shows a lack of significant pathological damage and the maintenance of good erectile function, even in longstanding cases.47 This is further supported by the reports of spontaneous resolution of priapism in many cases.48 In children another reasonable option is continuous perineal compression maintained by a strap on dressing.30

Surgical management of high flow priapism

The diagnosis of high flow priapism can be confirmed by colour Doppler ultrasonography and the causative vessel can be identified by selective arteriography. If any minor vessel is identified as the site of lesion, this can be catheterised superselectively and embolised. In practice, however, embolisation of the internal pudental artery on the affected side is the commonest procedure reported in the literature.30 This can be performed using absorbable material like gelatin sponge or autologous blood clot, or using non‐absorbable material like coils.47 Absorbable material causes temporary occlusion lasting for a day or two, and thereby lowers the risk of erectile dysfunction, but with a higher chance for recurrence. Non‐absorbable materials are superior in preventing recurrence, but pose a higher risk of future impotency. Cavernosal artery ligation is another option reserved in case of failures of embolisation.49

Brief review of other medical therapies

A brief discussion of other therapies is reviewed, but it must be made clear that these should not be used as part of routine treatment, as the evidence for their clinically use is not robust and based on small uncontrolled studies.

Saad et al, studied the use of hydroxyurea in patients with sickle cell disease presenting with priapism.50 Five patients were enrolled in the study, and four cases benefited by this treatment. After the initial treatment for the acute episode, all five patients developed stuttering priapism. Hydroxyurea was then introduced at the initial dose of 10 mg/kg, and as the hydroxyurea dose increased, the number or length of priapism episodes decreased. They suggested that hydroxyurea might prevent priapism episodes in sickle cell disease, probably at higher doses than usually prescribed for painful crisis prevention.50 Permenis et al recently reported the use of oral gabapentin in patients with recurrent, refractory, idiopathic priapism.51 All the three patients in this study responded to gabapentin within 48 hours and showed continued efficacy in preventing recurrences up to 24 months, when receiving a lower dose of the drug. Lowe et al evaluated the use of oral terbutaline in the treatment of priapism and reported a 36% efficacy as against 12% for placebo.52 However, Govier et al conducted a prospective randomised double blinded study with 24 patients and found no significant difference between terbutaline and placebo.53 Methylene blue, a guanylate cyclase inhibitor, is a potential inhibitor of endothelial mediated cavernous relaxation and has been used for the treatment of priapism. Its efficacy for priapism secondary to intracavernous drugs, was initially reported by Martinez et al.54 They reported 100% efficacy of this compound in 22 patients, with injection of 5 ml intracavernosally that was left in situ for five minutes. In addition, Hubler et al also reported similar efficacy with methylene blue in five patients.55 However, intracavernosal methylene blue therapy has not been successful in treating every case of priapism and should be reserved for cases not responding to conventional methods of treatment only.56 Oral baclofen, a γ‐aminobutyric acid agonist traditionally used to treat spasticity, at a dose of 40 mg/day has also been used with success in recurrent idiopathic nocturnal priapism not responding to other means of therapy.57

Conclusion

Priapism is a true urological emergency, and early intervention permits the best chance of functional recovery. Priapism must be defined as either a low flow (ischaemic) or a high flow (non‐ischaemic) type because the treatments and outcomes for these two types are significantly different.

Multiple choice questions (true (T)/false (F); answers at end of references

-

Regarding the epidemiology and aetiology of priapism:

Priapism has an incidence of 1.5 per 100 in the population

There is a bimodal peak of incidence of priapism

Leukaemia is the commonest aetiology in childhood

Pharmacological agents are the commonest aetiology in adults

Trauma is not an aetiology of priapism

-

Intracorporeal blood gas analysis in priapism:

Should be aspirated from the corpora spongiosum

Should be performed in an heparinised syringe

Shows pO2 of <30 mm Hg in low flow priapism

Shows a pH of >7.25 in low flow priapism

Shows a pCO2 of >60 mm Hg in high flow priapism

-

In the pathophysiology of priapism:

High flow priapism leads to the formation of arteriocavernous shunts, resulting in increased arterial flow into the cavernous tissue

Tissue anoxia and ischaemia are characteristically absent in high priapism

Risk of future erectile dysfunction secondary to ischaemia and subsequent fibrosis is high if not treated expeditiously, in the low flow type

Stuttering priapism is the recurrent self limiting episodes, which characteristically last for less than three hours

Priapism of the clitoris cannot occur

-

In the treatment of low flow priapism

The current management regimen is evidence based and according to the guidelines from the European Urological Association

Aspiration can be combined with flushing with normal saline or instillation of a vasoconstrictive agent such as phenylephrine

If priapism is of sickle cell aetiology, hypertransfusion is reserved for cases that fail the initial conservative treatment

In cases of priapism attributable to leukaemia, treatment with leukopheresis after failing aspiration may be necessary

The aim of surgical treatment of low flow priapism is to provide a shunt between the corpus cavernosum and glans penis, corpus spongiosum

-

In the treatment of high flow priapism

Non‐interventional management or observation has been recognised as a viable option

In children continuous perineal compression may be a successful treatment

The diagnosis of high flow priapism cannot be confirmed by colour Doppler ultrasonography

Selective arteriography can be used for successful embolisation

Embolisation can be performed through the internal pudental artery

Answers

1. (A) F, (B) T, (C) F, (D) T, (E), F; 2. (A) F, (B) T, (C) T, (D) F, (E) F; 3. (A) T, (B) F, (C) T, (D), T; (E) F; 4. (A) F, (B) T, (C) T, (D) T, (E) T; 5. (A) T, (B) T, (C) F, (D) T, (E) T.

Footnotes

Funding: none.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Hodgson D. Of gods and leeches: treatment of priapism in the nineteenth century. J R Soc Med 200396562–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papadopoulos I, Kelami A. Priapus and priapism: from mythology to medicine. Urology 198832385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shokeir A A, Hussein M I. The urology of Pharaonic Egypt. BJU Int 199984755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinman F. Priapism: report of cases in a clinical study of the literature with referance to its pathogenesis and surgical treatments. Ann Surg 191460689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripe J W. Case of continued priapism. Lancet 1845ii8

- 6.Hinman F., Jr Priapism: reasons for failure of therapy. J Urol 196083420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burt F B, Schirmer H K, Scott W W. A new concept in the management of priapism. J Urol 19608360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauri D, Spycher H K, Bruhlmann W. Erection and priapism: a new physiopathological concept. Urol Int 198338138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolodny R C, Masters W H, Johnson V E. Sex and urological illness. In: Textbook of sexual medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, 1979205–232.

- 10.Eland I A, van der Lei J, Stricker B H.et al Incidence of priapism in the general population. Urology 200157970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolbenstvedt A, Jenssen G, Hedlund H. Priapism of the glans and corpus spongiosum. Report of two cases with angiography. Acta Radiol 200344456–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winter C C, McDowell Experience with 105 patients with priapism: update review of all aspects. J Urol 1988140980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein E A, Montague D K, Steiger E. Priapism associated with the use of intravenous fat emulsion: case reports and postulated pathogenesis. J Urol 1985133857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fassbinder W, Frei U, Issantier R.et al Factors predisposing to priapism in haemodialysis patients. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 197612380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine F J, Saenz de Tagada I, Payton T R.et al Recurrent prolonged erections and priapism as a sequele of priapism: pathophysiology and management. J Urol 1991145764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin J L, Sharpe J R. Priapism and anaesthesia: new considerations. (Letter). J Urol 1983130371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnett A L. Pathophysiology of priapism: dysregulatory erection physiology thesis. J Urol 200317026–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munro D, Horne H W, Jr, Paull D P. The effect of injury to the spinal cord and cauda equina on the sexual potency of men. N Engl J Med 1948239903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravindran M. Cauda equina compression presenting as spontaneous priapism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 197942280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher J P. A lesson in neurology from the hangman. J S C Med Assoc 19959138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emond A M, Holman R, Hayes R J.et al Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med 19801401434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seftel A D, Saenz de Tejada I, Szetela B.et al Clozapine associated priapism: a case report. J Urol 1992147146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucur M, Mahmood T. Olanzapine‐induced clitoral priapism. J Clin Psychopharmacol 200424572–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brodie‐Meijer C C, Diemont W L, Buijs P J. Nefazodone induced clitoral priapism. Int Clin Psycopharmacol 199914257–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiGiorgi S, Schnatz P F, Mandavilli S.et al Transitional cell carcinoma presenting as clitoral priapism. Gynecol Oncol 200493540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amile R N, Bourgeois B, Huxtable R F. Priapism in preterm infant. Urology 19779558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leal J, Walker D, Egan E A. Idiopathic priapism in the new born. J Urol 1978120376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spycher M A, Hauri D. The ultrastructure of the erectile tissue in priapism. J Urol 1986135142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montague D K, Jarow J, Broderick G A.et al American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol 20031701318–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatzichristou D, Salpiggidis G, Hatzimouratidis K.et al Management strategy for the arterial priapism: therapeutic dilemmas. J Urol 20021682074–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mabjessh N J, Shemesh D, Abramowitz H B. Posttraumatic high flow priapism: successful management using duplex guided compression. J Urol 1999161215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muneer A, Cellek S, Dogan A.et al Investigation of cavernosal smooth muscle dysfunction in low flow priapism using an in‐vitro model. Int J Impot Res 20051710–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulmala R V, Tamella T L. Effects of priapism lasting 24 hours or longer caused by intracavernosal injection of vasoactive drugs. Int J Impot Res 19957131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegel J F, Rich M A, Brock W A. Association of sickle cell disease, priapism, exchange transfusion and neurological events: ASPEN syndrome. J Urol 19931501480–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponniah A, Brown C T, Taylor P. Priapism secondary to leukaemia: Effective management with prompt leukopheresis. Int J Urol 200411809–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Driel M F, Joosten E A, Mensink H J. Intracorporeal self‐injection with epinephrine as treatment for idiopathic recurrent priapism. Eur Urol 19901795–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald M, Santucci R A. Successful mamangement of stuttering priapism using home self‐injections of the aplha agonist metaraminol. Int Braz J Urol 200430121–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinberg J, Eyre R C. Management of recurrent priapism with epinephrine self‐injection and gonadotropin‐releasing hormone analogue. J Urol 1995153152–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winter C C. Cure of idiopathic priapism: new procedure for creating fistula between glans penis and corpora cavernosa. Urology 19768389–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winter C C. Priapism cured by creation of fistulas between glans penis and corpora cavernosa. J Urol 1978119227–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebbehoj J. A new operation for priapism. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 19748241–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nixon R G, O'Connor J L, Milam D F. Efficacy of shunt surgery for refractory low flow priapism: A report on the incidence of failed detumescence and erectile dysfunction. J Urol 2003170883–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacher E C, Sayegh E, Frensilli F.et al Cavernospongiosum shunt in the treatment of priapism. J Urol 197210897–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grayhack J T, McCullough W, O'Connor V., Jret al Venous bypass to control priapism. Invest Urol 19641509–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quackles R. Cure of a patient suffering from priapism by caverno‐spongiosa ansatomosis. Acta Urol Belg 1964325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rees R W, Kalsi J, Minhas S.et al The management of low‐flow priapism with the immediate insertion of a penile prosthesis. BJU Int 200290893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hakim L S, Kulaksizoglu H, Mulligan R.et al Evolvong concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of arterial high flow priapism. J Urol 1996155541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moscovici J, Barret E, Galinier P.et al Post‐traumatic arterial priapism in child: a study of four cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg 20001072–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shapiro R H, Berger R E. Post‐traumatic priapism treated with selective cavernosal artery ligation. Urology 199749638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saad S T, Lajolo C, Gilli S.et al Follow‐up of sickle cell disease patients with priapism treated by hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol 20047745–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Permenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Papathanasopoulos P.et al Gabapentin in the management of the recurrent, refractory, idiopathic priapism. Int J Impot Res 20041684–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowe F C, Jarow J P. Placebo‐controlled study of oral terbutaline and pseudoephedrine in management of prostaglandin E1‐induced prolonged erections. Urology 19934251–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Govier F E, Jonsson E, Kramer‐Levien D. Oral terbutaline for the treatment of priapism. J Urol 1994151878–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez‐Portillo F J, Fernandez Arancibia M I.et al Methylene blue: an effective therapeutic alternative for priapism induced by intracavernous injection of vasoactive agents. Arch Esp Urol 200255303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hubler J, Szanto A, Konyves K. Methylene blue as a means of treatment for priapism caused by intracavernous injection to combat erectile dysfunction. Int Urol Nephrol 200335519–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramos C E, Park J S, Ritchey M L.et al High Flow Priapism Associated with Sickle Cell Disease. J Urol 19951531619–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rourke K F, Fischler A H, Jordan G H. Treatment of recurrent idiopathic priapism with oral baclofen. J Urol 20021682552–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dodds P R, Batter S J, Serels S R. Priapism following ingestion of tamsulosin. J Urol 20031692302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Avisrror M U, Fernandez I A, Sanchez A S.et al Doxazosin and priapism. J Urol 2000163238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaidyanathan S, Soni B M, Singh G.et al Prolonged penile erection association with terazosin in a cervical spinal cord injury patient. Spinal Cord 199836805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Banos J E, Bosch F. Prazosin‐induced priapism. Br J Urol 198964205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sur R L, Kane C J. Sildenafil citrate‐associated priapism. Urology 200055950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shergill I S, Pranesh N, Hamid R.et al Testosterone induced priapism in Kallmann's syndrome. J Urol 20031691089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]