Abstract

Background and Aims

Butyrate enemas have been shown to be effective in treatment of ulcerative colitis, but the mechanism of the effects of butyrate is not totally known. This study evaluates effects of topical treatment of sodium butyrate (NaB) and 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) on the expression of trefoil factor 3 (TFF3), interleukin 1β (IL1β), and nuclear factor κB (NFκB) in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS) induced colitis in rats.

Methods

Distal colitis was induced in male Wistar rats by colonic administration of TNBS and colonically treated with NaB, 5‐ASA, combination of NaB and 5‐ASA, and normal saline for 14 consecutive days. Colonic damage score, tissue myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, TFF3 mRNA expression, serum IL1β production, and tissue NFκB expression were determined, respectively.

Results

Treatment of NaB, 5‐ASA, and the combination improved diarrhoea, colonic damage score, and MPO activities, increased TFF3 mRNA expression, and decreased serum IL1β production and tissue NFκB expression. The combination therapy of NaB and 5‐ASA had better effects than any other single treatment.

Conclusions

The combination of topical treatment of NaB and 5‐ASA was effective for relieving and repairing colonic inflammation and the effects were related to stimulation of TFF3 mRNA expression and down‐regulation of IL1β production and NFκB expression.

Keywords: sodium butyrate, 5‐aminosalicylic acid, trefoil factor 3, interleukin 1, nuclear factor κB

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) including two distinct disorders ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, are characterised by non‐specific intestinal inflammation. Although infectious agents, genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and dietary factors are taken into account for possible causes, the aetiology of IBD still remains unknown. Lately growing evidence1,2,3 has shown that an energy deficiency state of the colonic mucosa that may be secondary to impair production and utilisation of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) may link to the pathophysiology of IBDs. SCFAs are produced by the anaerobic bacterial fermentation of unabsorbed carbohydrates and fibre, and are rapidly absorbed and readily metabolised into ketone bodies and carbon dioxide by colonic epithelial cells. Of SCFAs, butyrate provides the primary energy source for colonic epithelium with 60%–80% undergoing metabolism.4,5 The dependence of colonic epithelia on SCFA metabolism increases from the proximal to the distal colon.6

Sodium butyrate (NaB) enema has been used in the treatment of IBD and obtained a beneficial effect either in vivo or in vitro.7,8,9 The mechanism of topical treatment of NaB may relate to its nutritional effect, which has shown to provide the energy source for colonic epithelium cells, accelerate aerobic metabolism of SCFAs, and regulate epithelium cell proliferation.10 Recently the inhibitory role of NaB for NFκB activation was found.11 However, its effects on the expression of trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) gene and other proinflammatory mediators of gut have not been evaluated.

Peptides of the trefoil factor family are characterised by a conserved motif known as the trefoil domain. This domain consists of some 40 amino acid residues in which six cysteines are disulfide linked forming a clover leaf structure. As one of the members of trefoil factor family, TFF3 containing a single trefoil domain is predominantly expressed in the goblet cells of small and large intestines of mammals12,13 and plays an important part in maintenance of epithelium integrity, protection, and wound healing. TFF3 can reinforce the stability of mucous protein, prevent colonic mucosa from pernicious substances, stimulate epithelial cell proliferation, and accelerate repair of the destroyed colonic mucosa.14,15,16

As TFF3 has shown mucosal protective effects, we are interested in studying effects of topical treatment of NaB and 5‐ASA that was widely used for treatment of IBD on mucosal expression of TFF3 gene, proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 1β(IL1β) production, and nuclear factor κB (NFκB) expression in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS) induced colitis in rats.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 200–250 grams were purchased from Hubei Provincial Experimental Animal Research Centre (Wuhan, China) and stayed in laboratory conditions for one week before experiments. They were housed in standard cages with laboratory chow and tap water ad libitum. A constant photoperiod (14 hours light and 10 hours dark) and constant temperature of 20°C were maintained. Procedures for care and handling of animals used in this study were approved by the ethics committee of Wuhan University medical school and carried out in accordance with guidelines established by the Wuhan University medical research centre. Before induction of colitis, rats were fasted for 24 hours and observed to ensure health. Weight of rats as well as diarrhoea was recorded daily.

Induction of colitis

Colonic inflammation was induced by a modification of the method described by Morris et al.17 On day 0, rats received intracolonic administration of 0.25 ml of 50% ethanol (vol/vol) containing 100 mg/ml TNBS. Briefly, a flexible plastic cannula with an outside diameter of 2 mm was inserted rectally into a lightly anaesthetised rat, and the tip was 8 cm proximal to the anus. After delivering the required dose of TNBS/ethanol solution, the cannula was left in the place for about 10 seconds, and then gently removed.

Experimental design

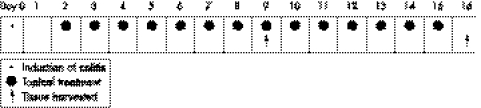

Figure 1 illustrates the time course of the model validation and topical treatment study. Ten rats (group A) were randomly selected as the empty control and received normal saline intracolonic instillation instead of TNBS. All other rats received TNBS enema on day 0. One day after colitis induction, 10 rats (group B) were treated by intracolonic administration of 1 ml of normal saline once a day as the positive control; 10 rats (group C) had topical treatment with 1 ml (100 mg/kg) of 5‐ASA once a day; 10 rats (group D) were treated 1 ml (80 mmol/l, pH 7.0) of NaB once a day; 10 rats in group E were given a combination of 1 ml (100 mg/kg) of 5‐ASA and 1 ml (80 mmol/l, pH 7.0) of NaB once daily. The treatment was consecutive for 14 days and rats (five per group) were killed on day 9 and day 16 after induction of colitis as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the time course of TNBS/ethanol induced colitis and the topical treatment and tissue harvested.

Assessment of macroscopic damage

The distal 10 cm of the rat colon and rectum was excised, opened longitudinally, and washed in saline buffer. Macroscopic damage was assessed by the scoring system of Wallace and Keenan,18 which takes into account the area of inflammation and the presence or absence of ulcers. The criteria for assessing macroscopic damage and the numerical rating score were as follows: 0: no ulcer, no inflammation; 1: no ulcer, local hyperaemia; 2: ulceration without hyperaemia; 3: ulceration and inflammation at one site only; 4: two or more sites of ulceration and inflammation; 5: ulceration extending more than 2 cm; 6–10: increment of one for each centimetre of ulceration greater than 2.

Assessment of microscopic damage

Colorectal tissue taken for histological examination was fixed overnight in 4% neutral buffered formalin, processed and sectioned in 4 μm thick sections, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Microscopic damage was quantified by image analysis of stained sections in a blinded fashion as follows.19 Mucosal ulceration: 0: no injury; 1: focal ulceration; 2: multifocal ulceration; 3: diffuse ulceration. Depth of injury was graded as follows: 0: no injury; 1: mucosal involvement only; 2: mucosal and submucosal involvement; 3: transmural involvement. The ulceration and depth of injury grades were scored and put together as a result ranging between the minimum of 0 and maximum of 6.

Measurement of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity

MPO is an enzyme found in primary granules of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and used as an index for the severity of digestive inflammation.20 Tissue MPO was detected by chromatometry using the kit purchased from the Jiancheng Biological Engineering Institute, Nanjin, China. MPO level was measured according to the kit specification strictly. One unit of MPO activity was defined as that degrading 1 μmol of hydrogen peroxide per gram of tissue at 37°C and expressed as unit per gram of tissue.

Measurement of TFF3 mRNA expression

mRNA extraction

When rats were killed, colonic tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction. The tissue was homogenised in TriZol (Promega, Madison, USA), followed by separation of RNA by three steps of phenol: chloroform extraction, isopropanol precipitation, and ethanol washing. After extraction, the concentration and purity of RNA was determined by spectrophotometry. One μg of total RNA with an A260/A280 ratio of more than 1.7 was used to generate cDNA using the RevertAID First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania).

Reverse transcribe polymerase chain reaction

One μg of total RNA from colon tissue was reverse transcribed (RT) with MMLV reverse transcriptase in a final volume of 20 μl. The mixture underwent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification for 35 cycles (40 s at 95°C, 40 s at 60°C, 60 s at 72°C). The sequences of primers of TFF3 (422 bp) were: sense, 5′‐ATGGAGACCAGAGCCTTCTGGAC‐3′, antisense, 5′‐AGAGGTTTGAAGCACCAGGGC‐3′; the primer for β‐actin (754 bp) sense, 5′‐TTGTAACCAACTGGGACGATATGG‐3′, antisense, 5′‐GATCTTGATCTTCATGGTGCTAGG‐ 3′. Aliquots of 15 μl of PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, photographed under ultraviolet light, and analysed with computer gel image analysis system.

Assessment of serum IL1β production

Serum Il1β production was determined by radioimmunoassay. Briefly, 2 ml of blood from heart was harvested and serum was isolated. Standard IL1β was serially diluted from 0.1 to 8.1 ng/ml by 0.1% BSA: PBS (RIA buffer). 125I‐IL1β (100 μl) and standard IL‐1β (100 μl) were mixed with 100 μl of standard rabbit anti‐IL1β monoclonal Ab or 100 μl of serum samples. Tubes were vortex mixed. After 24 hours incubation at 4°C, precipitation was performed by 500 μl of immune separating solution. The tubes were incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes and were centrifuged 3500 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and pellets were counted by a gammacounter. Concentration of serum IL1β was estimated from the standard curve by computer.

Expression of NFκB in colonic tissue

Expression of NFκB in formalin fixed and paraffin wax embedded colorectal tissue was assessed by method of immunohistochemistry. Briefly, the tissue sections were deparaffinised in xylene and rehydrated in descending ethanol series. After dewaxing and rehydration, the antigen retrieval was done by microwave for 15 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 20 minutes incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol at room temperature. The sections were incubated with 1:100 diluted specific polyclonal rabbit antirat NFκB p65 serum (NeoMarkers, Fremont, USA) for 12 hours at 4°C or incubated with 1:100 diluted normal rabbit serum in the same conditions as negative control. After PBS washing, the slides were incubated with a biotinylated horse peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody and 0.1% DAB substrate, using the standard streptavidin‐biotin based method.

Positive expression of NFκB was brown deposited granules in the cytoplasm and/or nuclear. For taking a count of 50 crypts in distal colon at random and count of percentage of positive cells in each crypt, the grades of expression of NFκB in mucosa were classified as follows: 0: less than 5%; 1: from 6% to 25%; 2: from 26% to 50%; 3: from 51% to 75%; 4: more than 75%.

Statistical analysis

The data were put into SPSS software (version 11.5, SPSS, Chicago, IL) and were expressed as means (SD). One way analysis of variance and Dunnett test were used for data analysis. A p value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Clinical manifestation

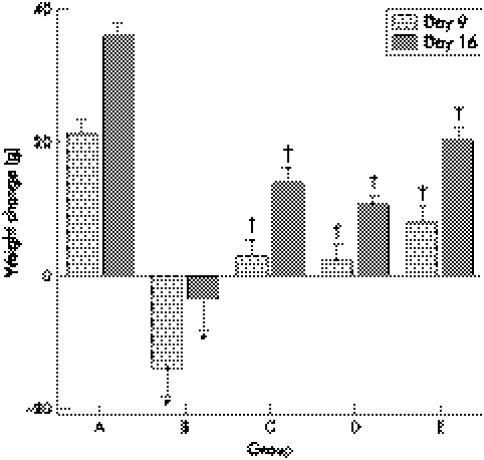

On day 0, body weight of rats was 221 (8) g in group A (n = 10) and 223 (12) g in TNBS treated groups (n = 40), which was a non‐significant difference between the groups. As shown in figure 2, the average weight gain in group A was 21 (2) g and 36 (2) g over the nine day period and 16 day period, respectively. Weight loss can be seen 14 (4) g and 4 (3) g on day 9 and 16 in group B, respectively. With the topical treatment with 5‐ASA and/or NaB, the body weight of rats increased on day 9 and 16 in groups C, D, and E, but was still lower than that in group A.

Figure 2 Weight change in groups A, B, C, D, and E. *Compared with group A, p<0.05; †compared with group B, p<0.05.

All animals in the TNBS groups had diarrhoea that lasted for different lengths of time. Diarrhoea persisted in eight (8 of 10) animals in group B, five (5 of 10) in group C, six (6 of 10) in group D, and three (3 of 10) in group E, respectively on day 9, and continued in three (3 of 5) animals in group B and only two (2 of 15) in the drug treated groups.

Macroscopic presentation

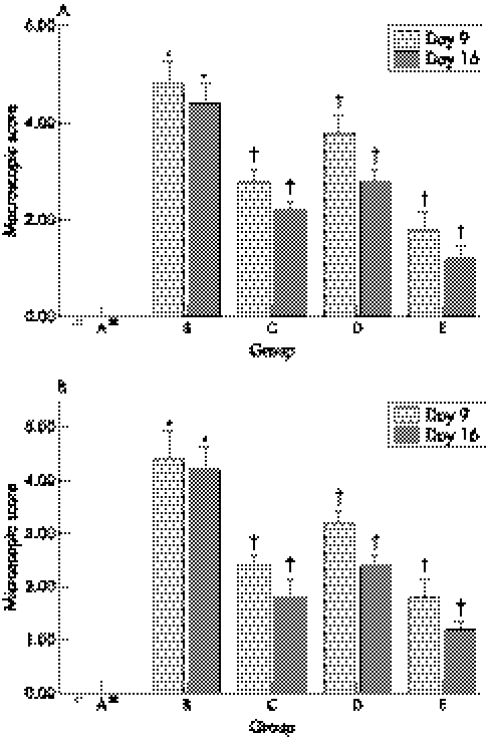

Macroscopic examination of the colon after TNBS induction showed colonic mucosal injury, hyperaemia, oedema, erosion, and ulceration. The macroscopic score in group B was much higher than that in group A. Compared with group B, colonic mucosal injury in NaB and 5‐ASA treatment groups was slight. Macroscopic scores for group C, D, and E were lower than those for group B (fig 3A), and the macroscopic scores for group E were the lowest among the groups.

Figure 3 Macroscopic (A) and microscopic (B) damage scores in groups A, B, C, D, and E. *Compared with group A, p<0.05; †compared with group B, p<0.05.

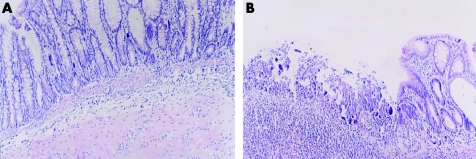

Histological evaluation

No colonic damage was found in group A on day 9 and 16 (fig 4A), but the histological manifestation in rats with TNBS induced colitis in group B showed a large number of neutrophil, monocyte, and eosinophil infiltration in mucosa and submucosa, ulceration, and mucosal damage (fig 4B). Compared with group A, colonic mucosal injury in group B was severe. Histological scores of group B were higher than those of the group C, D, and E and scores in group E were the lowest among the groups (fig 3B).

Figure 4 Effects of topical treatment with 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) and sodium butyrate (NaB) on TNBS induced colitis. (A) Group A, normal colonic mucosa (HE, ×200); (B) group B, inflammatory cell infiltration, ulceration on the day 9 (HE, ×200).

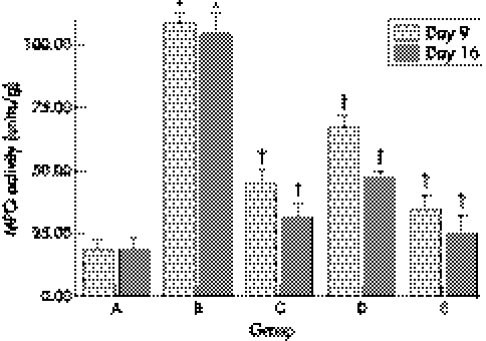

Tissue MPO activity

Tissue MPO activities in group A were all less than 20 units/g. A pronounced inflammatory response after TNBS induction was confirmed in group B by the significant rise in MPO activity from 19 units/g to 108 units/g on day 9 and to 104 units/g on day 16. On day 9 striking differences were seen between group B and group C, D, E (fig 5). On day 16, tissue MPO activities in group B were still kept at high level and significantly decreased in group C, D, E. MPO activities in group E were lower than those in groups C and D.

Figure 5 Tissue myeloperoxidase (MPO) activities in groups A, B, C, D, and E. *Compared with group A, p<0.05; †compared with group B, p<0.05.

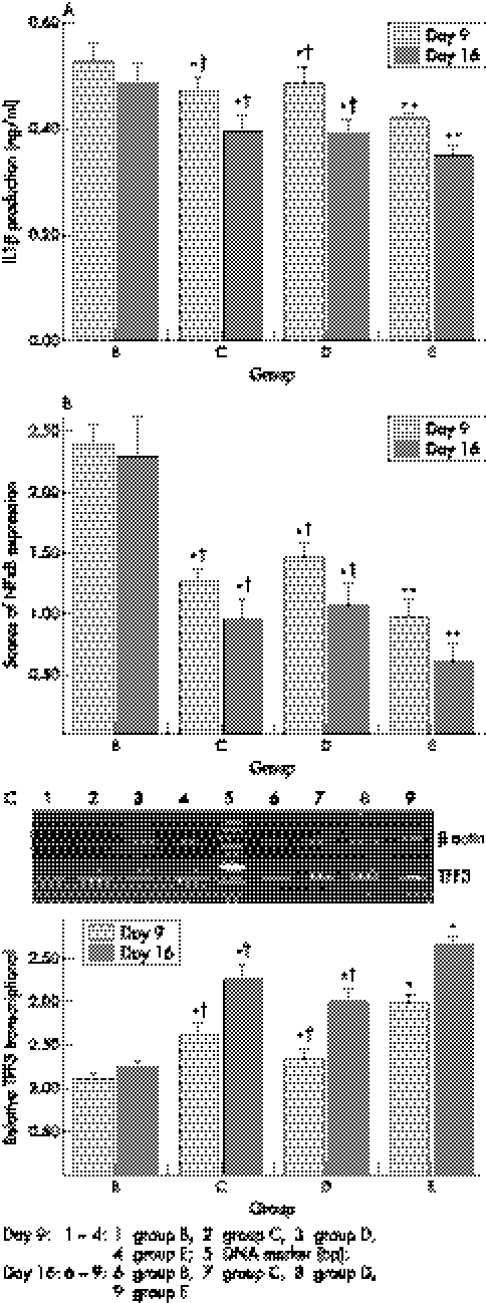

Interleukin 1β production

As shown in figure 6A, serum IL1β production in rats with TNBS induced colitis was high in group B and low significantly in group C, D, E on day 9 and 16 (p<0.05, respectively). IL1β level in group E was the lowest.

Figure 6 Effects of topical treatment with 5‐aminosalicylic acid and sodium butyrate on interleukin 1β production (ng/ml) (A), scores of NF‐κB expression (B) and transcription of TFF3 (C) in TNBS induced colitis in rats. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared with group B; †p<0.05 compared with group E.

Scores of NFκB expression

Levels of NFκB expression in colonic tissue were high in group B on day 9 and 16, and low in groups C, D, and E. NFκB expression in group E was the lowest (fig 6B).

TFF3 mRNA expression

RT‐PCR analysis showed increased TFF3 mRNA levels in colonic tissues in therapeutic groups. Transcriptional levels of TFF3 in groups C, D, and E were upregulated compared with group B on day 9 and 16, and group E was at highest level. (fig 6C).

Discussion

In this study, we saw that in TNBS induced colitis, which exhibits damage and repair profiles in accordance with IBD, topical administration of 5‐ASA and/or NaB improved the symptoms of colitis and promoted rapid repair of the epithelium in the active phase. This anti‐inflammatory effect was shown by decreasing colonic macroscopic and microscopic damage scores and inflammation index, MPO activity. Our study is consistent with the results described by Vernia et al2 who found that the effects of combined treatment with 5‐ASA and NaB were better than 5‐ASA enema alone in clinical management of ulcerative colitis.

We found that the strong reduction of TFF3 expression existed in a rat model of colitis and the level of TFF3 was increased during therapeutic period. Our results were consistent with Renes et al,21 which showed that TFF3 levels were decreased in the colon during active disease in dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis and upregulated during the recovery phase. Dossinger et al22 also reported that the 5‐ASA could activate TFF3 gene expression. Furthermore, time dependent and coordinated effects on increasing TFF3 expression were seen in the treatment group.

To elucidate the mechanism of upregulation of TFF3 by action of 5‐ASA and NaB, we presumed that the 5‐ASA and NaB might augment TFF3 mRNA expression in vivo by inhibition of IL1β induced NFκB activation. Upon stimulation of cells with stimuli IL1β, inhibitor (IκB) of NFκB gets phosphorylated and degraded, and allowing NFκB to translocate into the nucleus. Activated NFκB can induce the transcription of multiple genes involved in inflammation and also repress some gene expression,23,24,25,26 such as the human papilloma virus type 16 long control region (HPV16 LCR), the master chondrogenic factor Sox9 gene. The mechanism of repression has still to be described.

We confirmed that increasing expression of NF‐κB and IL1β paralleled a pronounced reduction in TFF3 expression in a rat model of TNBS induced colitis and decreased significantly in groups with continuous two week topical treatment with 5‐ASA and NaB. Our finding was identical to those that NaB and 5‐ASA can inhibit activation of IL1β induced NFκB in colonic mucosa.27,28,29,30,31 Recently Dossinger et al22 also reported a downregulation of TFF3 after IL1β stimulation in vitro and NFκB inhibitor, 5‐ASA could activate TFF3 gene expression. Loncar et al32,33 have shown that TFF3 expression was significantly reduced in some gastrointestinal cell lines with overexpression of NFκB and coexpression of a plasmid constitutively expressing specific NFκB inhibitor IκB. TFF3 downregulation was controlled by NFκB transcription factor. These studies shed light on the role of cytoprotection factor, TFF3 for inhibition of proinflammatory mediators, NFκB.

In conclusion, our studies have shown that topical treatment with 5‐ASA and NaB reduced IL1β and NFκB production and upregulated TFF3 gene expression, which provides more explanations for the NaB and 5‐ASA topical treatments in intestinal injury in human IBD.

Abbreviations

IBD - inflammatory bowel disease

SCFA - short chain fatty acid

TFF3 - trefoil factor 3

NaB - sodium butyrate

IL1β - interleukin 1β

NFκB - nuclear factor κB

5‐ASA - 5‐aminosalicylic acid

MPO - myeloperoxidase

TNBS - trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid

Footnotes

Funding: this study was supported by grants from Wuhan University science and technology creative foundation (301270059) and Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Foundation (2003AA301C08)

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Steinhart A H, Brzezinski A, Baker J P. Treatment of refractory ulcerative proctosigmoiditis with butyrate enemas. Am J Gastroenterol 199489179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vernia P, Annese V, Bresci G.et al Topical butyrate improves efficacy of 5‐ASA in refractory distal ulcerative colitis: results of a multicentre trial. Eur J Clin Invest 200333244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernia P, Cittadini M, Caprilli R.et al Topical treatment of refractory distal ulcerative colitis with 5‐ASA and sodium butyrate. Dig Dis Sci 199540305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman E N. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various soecies. Physiol Rev 198970567–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clausen M R, Mortensen P B. Kinetic studies on the metabolism of short‐chain fatty acids and glucose by isolated rat coloncytes. Gastroenterology 1994106423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roediger W E W. Role of anaerobic bacteria in the metabolic welfare of the colonic mucosa in man. Gut 198021793–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Q, Shimoyama T, Suzuki K.et al Effect of sodium butyrate on reactive oxygen species generation by human neutrophils. Scand J Gastroenterol 200136744–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatraman A, Ramakrishna B S, Shaji R V.et al Amelioration of dextran sulfate colitis by butyrate: role of heat shock protein 70 and NF‐kappaB. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003285177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarrerias A L, Millecamps M, Alloui A.et al Short‐chain fatty acid enemas fail to decrease colonic hypersensitivity and inflammation in TNBS‐induced colonic inflammation in rats. Pain 200210091–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavaglieri C R, Nishiyama A, Fernandes L C.et al Differential effects of short‐chain fatty acids on proliferation and production of pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines by cultured lymphocytes. Life Sci 2003731683–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luhrs H, Gerke T, Muller J G.et al Butyrate inhibits NF‐kappaB activation in lamina propria macrophages of patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 200237458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin J, Nadroo A M, Chen W.et al Ontogeny and prenatal expression of trefoil factor 3/ITF in the human intestine. Early Hum Dev 200371103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podolsky D K, Lynch‐Devaney K, Stow J L.et al Identification of human intestinal trefoil factor. Goblet cell‐specific expression of a peptide targeted for apical secretion. J Biol Chem 19932686694–6702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahm K B, Im Y H, Parks T W.et al Loss of transforming growth factor beta signaling in the intestine contributes to tissue injury in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 200149190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu K, Jiang S F, Lin M F.et al Extraction and purification of biologically active intestinal trefoil factor from human meconium. Lab Invest 200484390–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moro F, Levenez F, Durual S.et al Secretion of the trefoil factor TFF3 from the isolated vascularly perfused rat colon. Regul Pept 200110135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris G P, Beck P L, Herridge M S.et al Hapten‐induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology 198996795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace J L, Keenan C M. An orally active inhibitor of leukotriene synthesis accelerates healing in a rat model of colitis. Am J Physiol 1990258527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedorak R N, Empey L R, MacArthur C.et al Micoprostol provides a colonic mucosal protective effect during acetic acid‐induced colitis in rats. Gastroenterology 199098615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krawitz J E, Sharon P, Stenson F. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Gastroenterology 1995871344–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renes I B, Verburg M, Van Nispen D J.et al Epithelial proliferation, cell death, and gene expression in experimental colitis: alterations in carbonic anhydrase I, mucin MUC2, and trefoil factor 3 expression. Int J Colorect Dis 200217317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dossinger V, Kayademir T, Blin N.et al Down‐regulation of TFF expression in gastrointestinal cell lines by cytokines and nuclear factors. Cell Physiol Biochem 200212197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontaine V, Van der Meijden E, de Graaf J.et al A functional NF‐kappaB binding site in the human papillomavirus type 16 long control region. Virology 200027240–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Peef G W, Balzarano D.et al Novel NEMO/IkappaB kinase and NF‐kappa B target genes at the pre‐B to immature B cell transition. J Biol Chem 200127618579–18590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Massa P E, Hanidu A.et al IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ are each required for the NF‐κB‐mediated inflammatory response program. J Biol Chem 200227745129–45140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami S, Lefebvre V, de Crombrugghe B. Potent inhibition of the master chondrogenic factor Sox9 gene by interleukin‐1 and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha. J Biol Chem 20002753687–3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egan L J, Mays D C, Huntoon C J.et al Inhibition of interleukin‐1‐stimulated NF‐kappaB RelA/p65 phosphorylation by mesalamine is accompanied by decreased transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 199927426448–26453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zapolska‐Downar D, Siennicka A, Kaczmarczyk M.et al Butyrate inhibits cytokine‐induced VCAM‐1 and ICAM‐1 expression in cultured endothelial cells: the role of NF‐kappaB and PPARalpha. J Nutr Biochem 200415220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luhrs H, Gerke T, Boxberger F.et al Butyrate inhibits interleukin‐1‐mediated nuclear factor‐kappa B activation in human epithelial cells. Dig Dis Sci 2001461968–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inan M S, Rasoulpour R J, Yin L.et al The luminal short‐chain fatty acid butyrate modulates NF‐kappaB activity in a human colonic epithelial cell line. Gastroenterology 2000118724–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luhrs H, Gerke T, Schauber J.et al Cytokine‐activated degradation of inhibitory κB protein αis inhibited by the short‐chain fatty acid butyrate. Int J Colorect Dis 200116195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loncar M B, Al‐azzeh E D, Sommer P S.et al Tumour necrosis factor alpha and nuclear factor kappaB inhibit transcription of human TFF3 encoding a gastrointestinal healing peptide. Gut 2003521297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loncar M B, Al‐azzeh E D, Romanska H.et al Transcriptional control of TFF3 (intestinal trefoil factor) via promoter binding sites for the nuclear factor kappaB and C/EBPbeta. Peptides 200425849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]