Abstract

Background

Previous studies show that dietary fibre-rich foods with low energy density have a stronger effect on satiety per calorie compared to more energy dense foods.

Objective

To investigate subjective appetite and voluntary energy intake (24 h) after consumption of rye porridge breakfast and pasta lunch made from whole grain compared to iso-energetic reference meals made from refined cereals: wheat bread breakfast and wheat pasta lunch.

Subjects

In all, 22 healthy subjects, 14 females and 8 males, aged 21–64 years, BMI ranging from 18.7 to 27.5 kg/m2, participated.

Design

A randomised, crossover design was used. Appetite was rated by visual analogue scales (VAS) regularly from just before breakfast (08:00) until bedtime. An ad libitum dinner was served at 16:00. After leaving the clinic and in the morning day 2, subjects recorded foods consumed.

Results

Whole grain rye porridge gave a significantly prolonged satiety, lowered hunger and desire to eat (p<0.05 in most point estimates) up to 8 h after consumption compared to the refined wheat bread. The two pasta lunch meals did not vary in their effects on appetite ratings. There was no significant effect on ad libitum energy intake at 16:00 or self-reported energy and macronutrient intake in the evening and breakfast meal on day 2.

Conclusions

Whole grain rye porridge at breakfast has prolonged satiating properties up to 8 h after consumption compared to refined wheat bread, but did not diminish subsequent food intake.

Keywords: appetite, dietary fibre, whole grain, rye, porridge, pasta

Short-term appetite regulation is a complex network of psychological and physiological mechanisms occurring before, during and after a meal (1). Satiation occurs within a meal leading to its termination. This state is determined by factors occurring during the period of eating, such as cognitive influences, mouth feel and gastric distension. Satiety, on the other hand, arises in between meals. This state is induced by hormonal responses to food components in the stomach and small intestine as well as to absorbed nutrients in the blood stream (2). An increase in satiation and satiety per food calorie could help to decrease energy intake and thereby beneficially influence the rapidly growing global public health concern of obesity.

At a fixed energy level satiation and satiety vary depending on several aspects of the food composition. Most short-term studies comparing the relative impact of protein, carbohydrate and fat have found protein to be the most satiating macronutrient per calorie (3, 4). The satiating capacity among carbohydrate-rich foods varies largely depending primarily on energy density and dietary fibre (DF) content (5, 6). The majority of controlled short-term intervention trials show an association between high DF intake, both soluble and insoluble DF from a wide variety of sources, and increased satiety (7–10).

A great variation in satiating capacity (2 h after consumption) for various foods among and within food groups has been demonstrated (11). This was done by serving 1,000 kJ portions of a variety of foods to subjects who then rated their appetite every 15 min during 120 min. Appetite ratings depended on a number of factors; satiety was elevated by increased DF content, lowered energy density and increased cooked weight of the food. Among breakfast products, the highest satiety was induced by oat porridge. In order to further evaluate whole grain cereal porridge, we have studied the satiating effect (4 h) of oat versus rye porridge in comparison to wheat bread reference (12). The strong satiating capacity of porridge (11) was confirmed in that oat porridge induced a satiating effect significantly higher than that from wheat bread reference. The results from our study (12) also indicated that porridge made from rye flakes gave an even stronger effect than the oat porridge. The superior satiating properties of rye may have been due to a higher DF content. The main DF constituents of rye are partly soluble arabinoxylans, β-glucans, cellulose and also fructans (13). Further results (11) showed that pasta made from whole grain provided one of the highest satiety responses among the carbohydrate-rich foods. Although an increased satiety for whole grain porridge and pasta 2 h after consumption was shown (11), the study did not reveal the effect of the foods eaten as complete meals with additional foods, or the effects on satiety beyond 2 h after consumption.

Whole grain consumption has been suggested to reduce the risk for obesity (14) and related chronic disease such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease as well as for certain cancers (13). These health effects are likely to be mediated by DF and several bioactive compounds mainly located in the germ and bran parts of the cereal kernel may contribute.

The aims of the present study were to investigate subjective appetite and following voluntary energy intake after consumption of whole grain foods for lunch and breakfast, compared to refined grain foods. At breakfast a commercially available Swedish cereal, rye flakes (whole grain), was eaten as porridge. The lunch included pasta made from 100% whole grain wheat flour. The whole grain material used was whole grain as defined by the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC): ground or flaked grain containing endosperm, germ and bran in the same proportion as the intact kernel. As reference products we used bread for breakfast and pasta for lunch, both made from refined wheat.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Criteria for inclusion were the following: age between 20 and 60 years; body mass index (BMI) 20–27 kg/m2; regular eating habits meaning habit of consuming breakfast, lunch and dinner every day; fasting P-glucose 4–6 mmol/l; haemoglobin (Hb) in men 130–170, in women 120–150 g/l; alaninaminotransferase (ALT) 0.15–1.1 µkat/l; thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.3–4.0 mlE/l; willingness to comply with the study procedures; signed written informed consent and signed written biobank consent. Exclusion criteria were the following: intake of medicine likely to affect appetite or food intake; any medical condition involving the gastrointestinal tract; eating disorder; smoking; consumption of greater than three cups of coffee per day; change of body weight by more than 10% three months prior to screening; consumption of any specific diet such as vegan, vegetarian, gluten free, slimming, etc.; pregnancy, lactation or wish to become pregnant during the study period. At least 21 subjects (15) were planned to attend the study and 22 were recruited by advertisement in a local paper. Potential subjects were screened through a telephone interview before being recruited. Included subjects (n=22) were 14 women and 8 men, mean age 40.7 (SD±14.7) and with a mean BMI of 23.2 (SD±2.4). All met the criteria listed above and the health parameters were within the reference intervals. All 22 subjects completed the study.

Study design

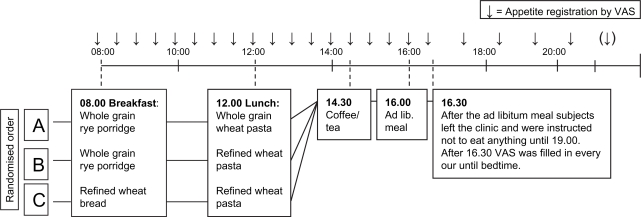

A randomised, crossover design was used to evaluate the effects on subjective appetite (hunger, satiety and desire to eat), ad libitum intake and self-reported energy intake 24 h after consumption of two iso-energetic breakfast (test and reference) and two iso-energetic lunch meals (test and reference). Each subject spent three weekdays at the clinic (08:00–16:30), separated by one week during which they followed their ordinary diet. On each test day they received one of three combinations of the two breakfasts and two lunch meals: the combinations are referred to as A, B or C as described in Fig. 1. The day prior to the test day subjects were instructed: not to conduct any heavy exercise or drink any alcoholic beverages; to avoid eating and drinking after 20:00 and to eat a similar type and amount of evening meal. Upon arrival at the clinic on the test day shortly before 08:00 the subjects had been fasting for 12 h. The breakfast meal was given at 08:00 and lunch at 12:00. Both meals had to be entirely consumed. Afternoon coffee/tea was served at 14:00 and an ad libitum meal at 16:00. Subjective appetite ratings were registered just before breakfast at 08:00 and then repeatedly every half hour between 08:30 and 16:00 and thereafter hourly until bedtime. During the study day the subjects were restricted to sedentary activities but were not allowed to sleep. After leaving the clinic at 16:30 the subjects were instructed not to eat or drink anything until 19:00. During the rest of the evening they were allowed to consume freely but were instructed to carefully record amounts and type of foods eaten until breakfast the day after. Schedule of events is described in Fig. 1.

Fig 1. .

Study events of the test day at the clinic. The two breakfast meals: whole grain rye porridge (test) and refined wheat bread (reference) and the two lunch meals: whole grain wheat pasta (test) and refined wheat pasta (reference) were combined into the three meal combinations A, B and C, which were eaten in a randomised order by each subject (n=22) at three separate occasions.

Meals

The test breakfast included rye porridge that was made from 62 g of whole grain rye flakes (AXA Rågflingor, Lantmännen Axa, Järna, Sweden) served as a hot porridge (rye flakes and 250 g water cooked for 3 min at 750 W microwave) and the reference breakfast included 71 g of refined wheat bread and 250 ml of water. The porridge and the bread were both served with 45 g of apple sauce, 5 g of margarine (40% fat), 200 g of milk (1.5% fat) and a cup of coffee or tea. The test lunch included 100 g (uncooked weight) of pasta made from whole grain wheat (Kungsörnen Fusilli Fullkorn, Lantmännen Axa, Järna, Sweden) and as reference food 94 g (uncooked weight) of pasta made from refined wheat (Kungsörnen Fusilli, Lantmännen Axa, Järna, Sweden) was used. Each portion of uncooked pasta was added to a full pot of boiling water and boiled for 12 min (whole grain pasta) or 9 min (refined wheat pasta) before being drained. Both pastas were served with 210 g of tomato sauce and 10 g of parmesan cheese (all additional foods were obtained from a local store). Energy and macronutrient composition of the test foods are given per 100 g in Table 1. The meals were composed so that the test and reference products contributed to about half of the total energy content of the complete meals. The lunch and breakfast were served in two energy levels to meet varying requirements of the subjects (based on BMI and physical activity) and the energy level was standardised for each subject between the three test days. All subjects but two consumed the lower energy level meals that are described in the text and tables. The higher energy level gave an extra 31% of energy. All meals were well balanced regarding energy and macronutrient composition and differed mainly in DF content and cooked weight (Table 2). Calculations were made using Dietist XP, version 3.0, Bromma, Sweden.

Table 1.

Energy and macronutrient content of the test and reference foods per 100 g (the pasta and rye flakes uncooked).

| Whole grain rye flakes | Refined wheat bread | Whole grain wheat pasta | Refined wheat pasta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kJ) (kcal) | 1,250 (300) | 1,100 (260) | 1,400 (330) | 1,500 (350) |

| Protein (g) | 10 | 8.5 | 13 | 12 |

| Fat (g) | 2.5 | 3.5 | 3 | 2 |

| Carbohydrate* (g) | 59 | 49 | 62 | 71 |

| Dietary fibre** (g) | 14 | 2.5 | 9.5 | 3 |

All values are the manufacturer's standard values and the exact values may vary between batches. The variation between batches for dietary fibre is around ±0.1%.

*Calculated value (total dry weight minus fat, protein, ash and dietary fibre).

**The dietary fibre content was analysed according to AOAC 45.4. 07/NMKL 129.

Table 2.

Energy and macronutrient composition of the complete breakfast and lunch meals, including test products and additional foods. The table shows the lower energy level; the higher energy level gave an extra 31%. All additional foods were obtained from a local store. Values are calculated from manufacturer's standard values. Calculations are made using Dietist XP, version 3.0, Bromma, Sweden.

| Breakfast meals |

Lunch meals |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Reference | Test | Reference | |

| Whole grain rye porridge | Refined wheat bread (71 g) | Whole grain wheat pasta | Refined wheat pasta | |

| (62 g rye flakes + 250 g water) | (100 g uncooked) | (94 g uncooked) | ||

| Additional foods | 45 g of apple sauce, 5 g of margarine (40% fat), 200 g of milk (1.5% fat) and a cup of coffee or tea | 210 g of tomato sauce and 10 g of parmesan cheese | ||

| Energy (kJ) (kcal) | 1,683 (402) | 1,658 (396) | 2,306 (551) | 2,302 (550) |

| Protein (g) | 13.4 | 13.1 | 19.3 | 17.6 |

| Fat (g) | 6.6 | 6.7 | 18.4 | 17.0 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 71.7 | 69.8 | 77.1 | 82.2 |

| Dietary fibre (g) | 9.0 | 2.6 | 12.6 | 5.9 |

| Total cooked weight (g) | 562 | 321 | 430 | 417 |

The ad libitum meal at 16:00 was served in excess portions (1,000 g) to measure voluntary food intake. The meal consisted of a common Swedish dish: a uniform hash of fried potatoes with beef, fried onions and herb mix (Axfood Oxpytt, Stockholm, Sweden) served together with beet roots. The energy content per 10 10 0 g was 550 kJ (170 kcal) (protein, 6 g; fat, 8 g; carbohydrate, 16 g). The subjects were instructed to eat until comfortably satiated. After they had left the clinic the food left on the plates was weighed for calculation of the amount of energy eaten. The purpose of the ad libitum meal was not known to the subjects.

During the first test occasion, subjects could drink water without restraint. At 14:00 coffee or tea (2 dl) was served with milk and sugar by the decision of the subjects. At the two following test occasions all drinks including water were kept identical, within subjects, to those consumed on the first test day.

Subjective appetite measures

A handheld computer (Palm z22, China. Software supplied by Centre for Human Studies of Foodstuffs, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to monitor subjective feelings of hunger, satiety and desire to eat (16) just before breakfast and then at every half hour between 08:30 and 16:00, thereafter hourly until bedtime. The handheld computer was programmed to beep when the subject should answer the questions. Then three unipolar scales were shown on the computer screen, one at a time, displaying: “how hungry do you feel right now?”, “how full do you feel right now?” and “how strong is your desire to eat right now?”. Each scale was marked, respectively: not at all hungry/extremely hungry, not at all satisfied/extremely satisfied, extremely strong/not at all strong. The specific value of each registration is presented by the computer as a number from 0 to 100, measured from the left of the scale to the mark made by the subject. The use of hand computers rather than pen and paper assures that monitoring occurs according to schedule and prevents the subjects from comparing with previous ratings.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 14, LEAD Technologies, Inc., USA). The level of significance was set at p<0.05. Paired t-tests were performed for comparisons of appetite ratings at single time points and energy intake at the ad libitum meal as well as self-reported energy intake in the evening of the test day and the morning on day 2.

Results

Intake of the test meals

All the subjects finished the breakfast and lunch meals completely according to instructions. No adverse events were recorded and no one had problems finishing the test meals.

Subjective appetite measures

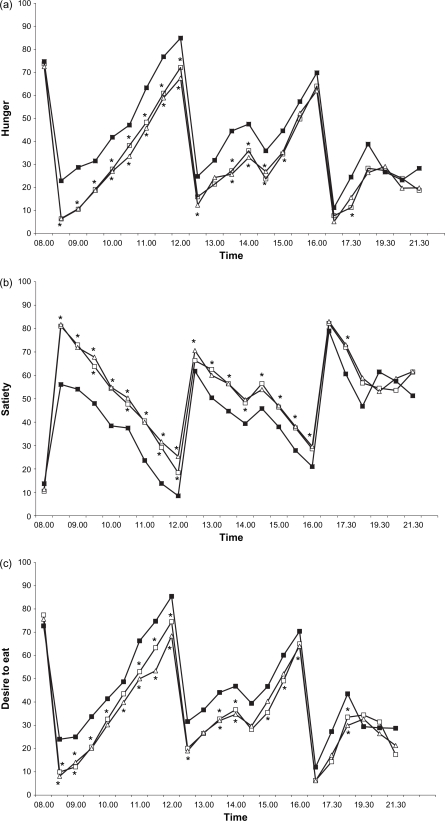

At each test day morning subjects rated their appetite similarly. That is, there was no significant difference for mean rated hunger, satiety or desire to eat at baseline between the three test days. The mean values at each time point after breakfast showed a clear effect of time. Ratings for satiety, hunger and desire to eat followed the same pattern (Fig. 2a–2c). A comparison between the meal combinations B (whole grain rye porridge breakfast/refined wheat pasta lunch) and C (refined wheat bread breakfast/refined wheat pasta lunch) shows that the subjective feelings of hunger were significantly lower after rye porridge breakfast compared to the refined wheat bread breakfast at every time point between 08:30 and 12:00 (Fig. 2a). Also after consumption of the refined wheat pasta lunch meal at 12:00 the subjects who had eaten the rye porridge breakfast continued to rate lower feelings of hunger until 16:00, with exception of time points 13:00 and 15:30 where the difference did not reach statistical significance. Satiety and desire to eat followed the same pattern (Fig. 2b and 2c). A comparison of diets A and B, both of which included rye porridge for breakfast but different lunch meals, revealed that type of pasta did not affect any of the subjective appetite measures. An additional observation indicated that the coffee served at 14:00, at all occasions, resulted in a trend towards decreased hunger and increased satiety.

Fig 2. .

Mean subjective ratings for hunger (Fig. 2a), satiety (Fig. 2b) and desire to eat (Fig. 2c) (n=22) after consumption of meal combinations A (−□ − ), B (−Δ − ) and C (−▪ − ) in a randomised order at three separate occasions. *Significantly different from C (p<0.05 at that specific time). A, whole grain rye breakfast/whole grain wheat pasta lunch; B, whole grain rye breakfast/refined wheat pasta lunch; C, refined wheat bread breakfast/refined wheat pasta lunch.

Food intake measures

Despite diverse appetite responses to the test meals, there were no significant effects on ad libitum energy intake at 16:00 or self-reported energy (Table 3) and macronutrient intake (data not shown) in the evening and breakfast on day 2.

Table 3.

Voluntary energy intake (kJ), mean±S.D., at the ad libitum dinner (16.00) and self-reported energy intake after 19.00 (after subjects had left the clinic) as well as self-reported energy intake at breakfast day 2. No difference was seen in energy intake or macronutrient composition (data not shown) between test days.

| Meal combination A | Meal combination B | Meal combination C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ad libitum meal at 16.00 | 2,320±874 | 2,376±877 | 2,294±917 |

| Self–reported intake on the test day after 19.00 | 2,107±1089 | 2,150±1042 | 2,220±1080 |

| Self–reported intake at breakfast on day 2 | 1,574±543 | 1,624±574 | 1,486±585 |

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that non-supplemented, commonly used foods, refined wheat bread and rye porridge, eaten as part of iso-energetic breakfast meals with similar macronutrient composition, varied considerably in their respective effects on subjective appetite up to 8 h after consumption. The main difference in composition of the two breakfast meals was DF content. But also processing (flakes versus flour) and cooking method differed, the porridge being more energy diluted due to higher water content and therefore served in larger portion size in order to provide the same amount of energy as the bread. Particle size of cereal grains have been shown to influence postprandial satiety, glucose and insulin responses (17, 18). Water incorporated into a food, but not served with a food, decreases energy intake at a directly following meal (19). Furthermore, the early response may have been affected by a difference in palatability. Certainly, the satiating effect of the porridge compared to the bread depends on a combination of these factors.

The mechanisms underlying the satiating effects were not investigated in the present study. However, the satiating properties of DF have been related to several stages in the physiological processes of short-term appetite regulation (7). Those include bulking effects resulting in increased extension of the stomach and, for some viscose DF, delayed gastric empting causing early signals of satiation to increase. Furthermore, pre-absorptive hormonal signalling at the level of the small intestine is essential in the induction and maintenance of satiety. DF that delay absorption of nutrients may therefore lead to prolonged satiety by increasing the time that macronutrients are in contact with the absorptive surfaces. Finally, end products caused by colonic fermentation of DF, such as acetate and propionate, have been proposed to affect satiety. How this effect is mediated is not clear. Suggested mechanisms are stimulated release of satiety hormones: GLP-1, PYY, by L-cells in the colon (20) and through a delay of gastric emptying (21). The increased satiety during the afternoon, seen in the present study after a high intake of rye fibre for breakfast, may be explained by colonic events.

The two lunch meals, whole grain wheat pasta versus refined wheat pasta, did not differ in any of the subjective appetite ratings. These lunch foods had similar cooked weight, appearance and texture and mainly differed in DF content from wheat bran.

The fact that there was no difference in voluntary food intake at 16.00, in the evening or during the following morning is important to consider. In order for the increase in satiety to contribute to maintenance of energy balance, a spontaneous decrease in voluntary food intake is necessary. When using an ad libitum meal as a marker for how a test meal affects following voluntary food intake, the timing of the ad libitum meal is central; and the fact that there was no significant difference in hunger at the time of the ad libitum meal implies that the meal was planned too late to reflect the differences in hunger that occurred earlier in the day. This study was, however, primarily designed to measure appetite over the course of the day under energy-standardised conditions, which ruled out an earlier ad libitum meal. The controlled conditions between 08:00 and 16:00 may have hidden possible effects that rye porridge may provoke in a real life situation, where the availability of food often is unlimited at every hour. One may also speculate that less would be eaten if the rye porridge was served ad libitum, due to its relatively low energy density.

This study has shown that a breakfast based on whole grain rye flakes served as a hot porridge compared to reference wheat bread in a complete breakfast meal gave a significantly increased satiety, subsequent decreased hunger and desire to eat up to 8 h after consumption. However, no effect could be demonstrated on subsequent food intake.

Conflict of Interest and Funding

This study was financed by the producer of the test products, Lantmännen Food R & D, Sweden and conducted by KPL – Centre of Human Studies of Foodstuffs, Uppsala, Sweden (now KPL Good Food Practice AB). KPL is working on commission from clients in food industries and food science. KPL is working independently from the clients.

References

- 1.Blundell JE, Green S, Burley V. Carbohydrates and human appetite. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59(Suppl 3):728S–734. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.3.728S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):13–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenstein J, Roberts SB, Dallal G, Saltzman E. High-protein weight-loss diets: are they safe and do they work? A review of the experimental and epidemiologic data. Nutr Rev. 2002;60((7 Pt 1)):189–200. doi: 10.1301/00296640260184264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westerterp-Plantenga MS. The significance of protein in food intake and body weight regulation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6(6):635–8. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt SH, Brand-Miller JC, Stitt PA. The effects of equal-energy portions of different breads on blood glucose levels, feelings of fullness and subsequent food intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(7):767–73. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pai S, Ghugre PS, Udipi SA. Satiety from rice-based, wheat-based and rice-pulse combination preparations. Appetite. 2001;44(3):263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton-Freeman B. Dietary fibre and energy regulation. J Nutr. 2000;130(2S Suppl):272S–5S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.272S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howarth NC, Saltzman E, Roberts SB. Dietary fibre and weight regulation. Nutr Rev. 2001;59(5):129–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb07001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Dietary fiber and body-weight regulation. Observations and mechanisms. Ped Clin North Am. 2001;48(4):969–80. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slavin JL, Green H. Dietary fibre and satiety. Nutr Bull. 2007;32(s1):32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt SH, Miller JC, Petocz P, Farmakalidis E. A satiety index of common foods. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49(9):675–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaksson H, Fredriksson H, Åman P. The effect of cereal based breakfast meals on satiety and voluntary energy intake. In: Tetens I, editor. Programme & abstract book, 9th Nordic Nutrition Conference. Copenhagen, Denmark: 2008. p. 69. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamal-Eldin A, Åman P, Zhang J-X, Bach Knudsen K-E, Poutanen K. Rye bread and other rye products. In: Hamaker BR, editor. Technology of functional cereal products. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2007. pp. 233–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams PG, Grafenauer SJ, O'Shea JE. Cereal grains, legumes, and weight management: a comprehensive review of the scientific evidence. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(4):171–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(1):38–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, Rowley E, Reid C, Elia M, et al. The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: a review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings. Br Nutr. 2000;84(4):405–15. doi: 10.1017/s0007114500001719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt SH, Miller JB. Particle size, satiety and the glycaemic response. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48(7):496–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaton KW, Marcus SN, Emmett PM, Bolton CH. Particle size of wheat, maize, and oat test meals: effects on plasma glucose and insulin responses and on the rate of starch digestion in vitro. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47(4):675–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.4.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Thorwart ML. Water incorporated into a food but not served with a food decreases energy intake in lean women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(4):448–55. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters HPF, Mela DJ. The role of the gastrointestinal tract in satiation, satiety, and, food intake: evidence from research in humans. In: Harris RBS, Mattes RD, editors. Appetite and food intake: behavioral and physiological considerations. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2008. pp. 187–211. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ropert A, Cherbut C, Rozé C, Le Quellec A, Holst JJ, Fu-Cheng X, Bruley des Varannes S, Galmiche JP. Colonic fermentation and proximal gastric tone in humans. Gastroenterology. 1996;111(2):289–96. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]