Abstract

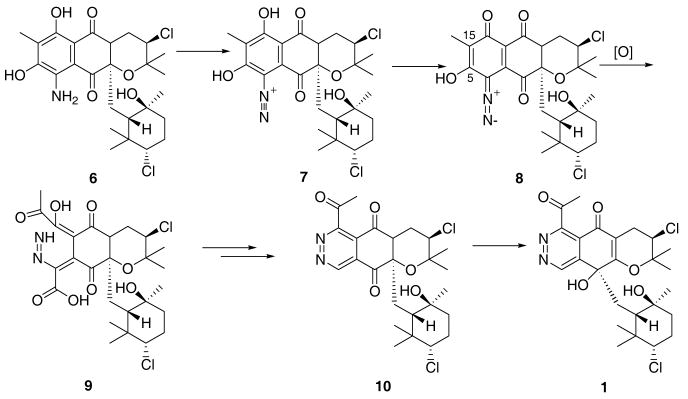

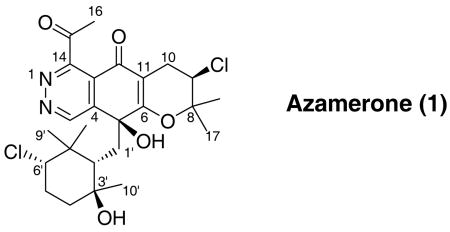

A novel meroterpenoid, azamerone, was isolated from the saline culture of a new marine-derived bacterium related to the genus Streptomyces. Azamerone is composed of an unprecedented chloropyranophthalazinone core with a 3-chloro-6-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexylmethyl side chain. The structure was rigorously determined by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. A possible biosynthetic origin of this unusual ring system is proposed.

For several years, our laboratory has been interested in culturing actinomycetes from marine sediment samples with the goals of developing their potential as a source of new marine-derived pharmaceuticals1 and understanding their biological diversity in the oceans.2 In 2002, we cultured several actinomycete strains, designated MAR4, which appear to represent a new species within the genus Streptomyces.3 Our initial chemical explorations of the secondary metabolites produced by strains belonging to this group indicate that they produce predominantly meroterpenes, which are highly unusual for actinomycetes.4,5 A more recent investigation of one MAR4 strain in particular, our strain CNQ766, led to the identification of two new polyketides6 and an unusual meroterpenoid phthalazinone, azamerone (1).7 It is the isolation and structure elucidation of this latter compound we now wish to report. This represents the first example of this unique phthalazinone ring system as a natural product.8

Strain CNQ766 was cultured and the extract fractionated as previously described.6 Seven mg of pure azamerone (1, tR = 45 min) was obtained from the actinofuranone-containing fraction by RP-HPLC eluting with 55% CH3CN in water. The colorless crystals, which were obtained from a mixture of EtOH and DCM, had a molecular composition of C25H32Cl2N2O5 based on the HRESITOF-MS data (obsd [M+H]+ at m/z 511.1762). The isotope ratio (5:3) between the [M+H]+ and [M+H+2]+ pseudo-molecular ion peaks in the ESI mass spectrum clearly indicated that 1 contained two chlorine atoms.9 These data also indicated azamerone contained 10 double bond equivalents, which based on the carbon chemical shifts were initially attributed to two carbonyls, two C=C double bonds, two C=N double bonds and 4 rings. The IR spectrum was consistent with the presence of hydroxyl (3372 cm−1) and carbonyl functional groups (1720 cm−1) supporting some of the preliminary assignments that were made from analysis of the carbon NMR data.

Several substructures were assigned by analyses of the 1H, 13C, 1H-1H COSY, HMBC, and HMQC NMR spectral data recorded in CD3OD (Table S1 in supporting information). Substructure A was elucidated starting from the tertiary methyl proton singlets (H-17 and H-18) that showed HMBC correlations to one another, to C-8 and to C-9. The proton signal attached to this latter carbon C-9 (δH 4.33, dd) showed a COSY correlation to the diastereotopic methylene proton signals H2-10, which in turn showed HMBC correlations to a carbonyl (C-12) and two olefinic quaternary carbons C-6 and C-11. The chemical shifts of these three carbons, along with the characteristic proton and carbon chemical shifts of C-9 (δH 4.33/δC 59.3),9 established this partial structure as a chlorinated dihydropyran ring (A).

Substructure B was constructed starting from the methyl proton (H-10′) that showed HMBC correlations to C-2′ (δC 42.6), C-3′ (δC 72.4), and C-4′ (δC 51.3). This fragment was expanded by a series of COSY correlations between the proton attached to this latter carbon (C-4′) to H-5′ and from H-5′ to H-6′. Finally, HMBC correlations from H-6′ to the methyl groups C-8′ (δC 16.4) and C-9′ (δC 29.2) and from the proton signals of these gem-methyl groups back to the methine carbon C-2′ established this as a substituted cyclohexane ring. Since the 1H and 13C NMR data of this unit were very similar to those of a 3-chloro-6-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexyl-methyl moiety we previously reported in the literature5a the hydroxyl and chloro functional groups were attached to C-3′ and C-6′, respectively.

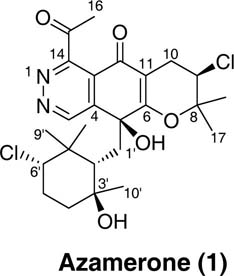

Substructures A and B were then connected based on an HMBC correlation from the methylene proton signal (H-1b′ δH 1.95) to the olefinic carbon C-6 at δC 172.8. This methylene proton signal (H-1b′) also showed HMBC correlations to oxygenated quaternary (C-5; δC 71.6) and olefinic carbon signals (C-4; δC 146.5). These signals in turn showed HMBC correlations from H-3, a proton whose chemical shift was characteristic of a heteroaromatic proton signal,9 which gave substructure C (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Partial structures and possible structures of azamerone

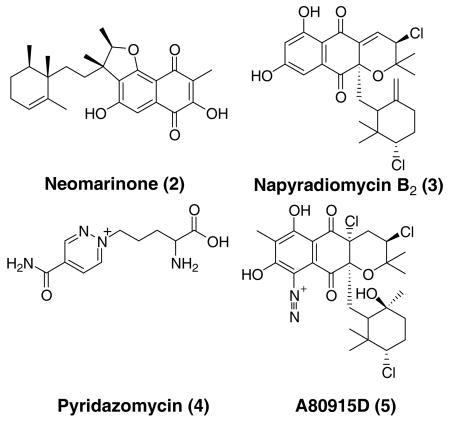

Only two other connectivities could be gleaned from the spectral data. First, the remaining methyl proton signal (H-16) at δH 2.60 showed HMBC correlations to a carbonyl carbon (C-15) and to the quaternary carbon C-14 suggestive of the acetyl substructure D. Finally, based on chemical shift considerations, the remaining hydroxyl group, mandated by the molecular formula, was attached to C-59 leaving two possible structures for azamerone, E and F (Figure 1). A comparison of 13C NMR data for simple substituted isoquinoline analogues of E10 and F11 strongly suggest E as the correct structure (δC13 124.5 in 1 and δC13 121.8 and δC13 145.4 in the ring analogues of E and F, respectively.)12

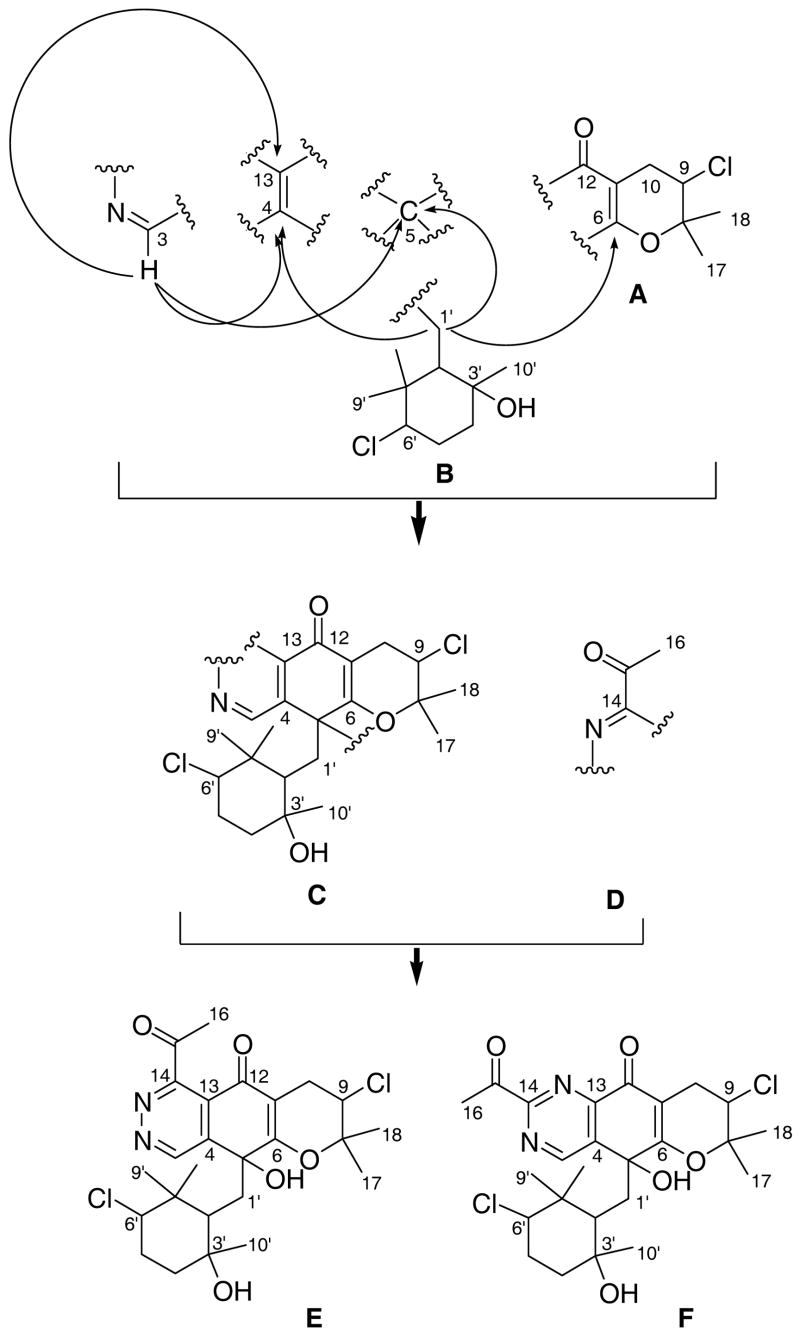

In the end, because the proposed structure was so unusual, 1 was crystalized from a mixture of EtOH-DCM (200 mL - 3 drop). This provided orthorhombic crystals for X-ray analysis the result of which confirmed the assigned structure of 1 (Figure 2) and assigned a relative configuration consistent with the observed NOE correlations (See supporting information). The absolute configuration could be assigned as depicted on the basis of the diffraction anisotropy of the chlorine atom thus clearly defining azamerone as a 5S,9R,2′S,3′S,6′S-terpenoid-dichloro-acetyl-phthalazinone. The most structurally intriguing part of this compound is the phthalazinone ring system, which has never been described before in a natural product. Synthetic compounds, which are truncated versions of the core of 1, have been prepared to explore their biological activity and use as dienophiles.8 As such, heterocyclic quinones containing this phthalazine-5-8-quinone core, are well-known as DNA intercalating agents that act as topoisomerase inhibitors.13 Compound 1 displays weak in vitro cytotoxicity against mouse splenocyte populations of T-cells and macrophages with an IC50 value of 40 μM, though it is not clear whether this activity is due to inhibition of a topoisomerase.

Figure 2.

ORTEP Representation of 1

The meroterpenoid structure of azamerone is also of interest because actinomycetes are not traditionally known to produce terpenoids.14 Surprisingly, this appears to be a hallmark of MAR 4 strains3,4 as two other classes of meroterpenoids have been isolated from these organisms.5 In the case of one of these classes of compounds, neomarinone (2),5b feeding studies have established that the monoterpene side chain originated from the nonmevalonate pathway.15 The other class of compounds are prenylated naphthoquinones such as 3,9a,16 and while no biosynthetic studies on this class have been carried out using MAR 4 strains, feeding studies in Steptomyces aeriouvifer have established that the quinone core of a compound, which is structural related to 3, is acetate-derived while the monoterpene unit arises, in that case, via the mevalonate pathway.17 In the case of 1, it is not clear which pathway gives rise to the terpene units.

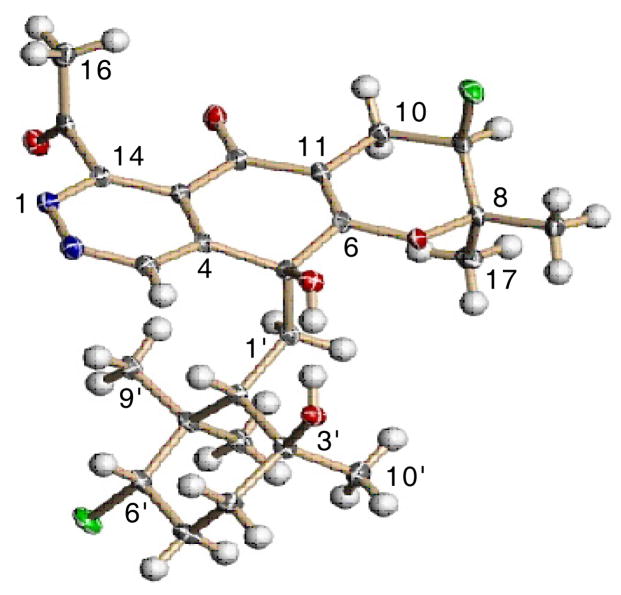

The structure of 1 also raises some intriguing questions regarding the biosynthesis of the pyranophthalazinone ring system and in particular how the N-N bond is incorporated into the carbon backbone.18 Feeding studies on the antifungal antibiotic pyridazomycin (4) have established that the nitrogen atoms of the pyridazine ring are derived from two different amino acids.19 Likewise the carbon backbone and two nitrogen atoms in the well-known cyclic piperazic acid units are glutamine derived.20 While this is possible in the case of azamerone, which would mean 1 is an amalgamation of terpene, amino acid and polyketide biosynthetic pathways, it seems unlikely given the results of the acetate feeding studies previously described with S. aeriouvifer. An alternative intriguing proposal arises after considering the relationship of 1 to other merotepenoids isolated from MAR4 and other Streptomyces strains. Numerous naphthoquinones, such as 3, are produced by strain CNQ766 along with 1, and known members of this structural class include the diazanaphthoquinone 5.21 Could 1 be formed by an oxidative rearrangement of a aryldiazonium such as 7? Figure 3 outlines a biosynthetic scheme involving compound 7, 11-descholoro-5,22 which potentially could be derived from the corresponding amino-derivative analogous to kinamycin biosynthesis.23 Initial oxidative cleavage of the aromatic ring of 8 between C-5/15 followed by cyclization and decarboxylation would form the methyl ketone 10. The exact timing of this decarboxylation is unknown since mechanisms involving decarboxylation before and after24 cyclization are plausible. A subsequent 1,2 alkyl shift of the 3-chloro-6-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexylmethyl side chain would afford 1. This intriguing biosynthetic origin of 1 is currently under investigation.

Figure 3.

Hypothetical Biosynthesis of Azamerone

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is a result of generous support from the National Cancer Institute (CA44848), the 500 MHz NMR spectrometer was funded by the NIH Shared Resources Program (S10RR017768) and JYC was partially supported by a Korea Research Foundation Grant from the Korea Government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund; KRF-2003-214-C00198). We thank Drs. I. E. Soria-Mercado and A. Rheingold for assistance with the crystallization and the acquisition of X-ray diffraction data. We also thank W. Strangman for providing bioasssay data and J. Winters and B. Moore for disscussions on the biosynthesis of 1. C. Kauffman is thanked for assistance with the fermentation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Tabulated NMR data, 1H, 13C and 2D NMR spectra and CIF data for crystal structure are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Williams PG, Buchanan GO, Feling RH, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6196–6203. doi: 10.1021/jo050511+. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen PR, Mincer TJ, Williams PG, Fenical W. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;87:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s10482-004-6540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen PR, Gontang E, Mafnas C, Mincer TJ, Fenical W. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1039–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Moore BS, Kalaitzis JA, Xiang L. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;87:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s10482-004-6541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jensen PR, Fenical W. In: Natural Products: Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Medicine. Zhang L, Demain AL, editors. Humana Press; New Jersey: 2005. pp. 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- 5.For examples see Soria-Mercado IE, Prieto-Davo A, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:904–910. doi: 10.1021/np058011z.Pathirana C, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:7663–7666.Hardt IH, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:2073–2076. This structure has been recently revised based on stable isotope feeding studies, see Moore 2003 (Ref 15).

- 6.Cho JY, Kwon HC, Williams PG, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Nat Prod. 2006;2006(69):425–428. doi: 10.1021/np050402q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azamerone (7 mg from 30 L culture, 0.21% yield): colorless crystal; [α]D - 8.8 (c 0.0025, MeOH); mp 210–212 °C; IR (neat) νmax 3372, 2929, 2860, 1720, 1640, 1616, 1447, 1337, 1238, 1127, 1075, 1022, 952 cm−1; UV (MeOH) λmax (logε); 217 sh (3.9), 250 sh (3.4), 323 (3.3) nm; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) and 13C (125 MHz, CD3OD), see Table S1; HRESITOF-MS [M+H]+ m/z 511.1762 and [M+Na]+ 533.1586 (C25H33Cl 2N2O5, calcd. 511.1764).

- 8.For synthetic “analogues” see Parrick J, Ragunathan R. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1993;2:211–216.

- 9.Pretsch E, Buhlmann P, Affolter C. Structure Determination of Organic Compounds. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petitt GR, Knight JC, Collins JC, Herald DL, Pettit RK, Boyd MR, Young VG. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:793–798. doi: 10.1021/np990618q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderberg PI, Luck IJ, Harding MM. Magn Reson Chem. 2002;40:313–315. [Google Scholar]

- 12.A reviewer suggested 15N NMR could have distingushed E and F. Indeed, the nitrogen atoms in the pyridazine (E) and pyrimidine (F) analogues should resonate at approximately 400 and 300 ppm, respectively. See Rao NS, Rao GB, Murthy BN, Das NM, Prabhakar T, Lalitha M. Spectrochim Acta, Part A. 2002;58:2737–2757. doi: 10.1016/s1386-1425(02)00016-1.

- 13.Kim JS, Lee HJ, Suh ME, Choo HYP, Lee SK, Kim C, Park SW, Lee CO. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:3683–3686. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuzuyama T, Seto H. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:171–183. doi: 10.1039/b109860h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalaitzis JA, Hamano Y, Nilsen G, Moore BS. Org Lett. 2003;5:4449–4452. doi: 10.1021/ol035748b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiomi K, Nakamura H, Iinuma H, Naganawa H, Hiroshi I, Takeuchi T, Umezawa H. J Antibiot. 1986;39:494–501. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.494. Several compounds within this structural class were isolated from a MAR 4 strain during the work described in reference 5a

- 17.Seto H, Watanabe H, Furihata K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7979–7982. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For examples of other compounds containing an N-N bond see Hughes P, Clardy J. J Org Chem. 1989;54:3260–3264.Nakagawa M, Hayakawa Y, Furihata K, Seto H. J Antibiot. 1990;43:477–484. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.477.

- 19.Bockholt H, Beale JM, Rohr J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1994;33:1648–1651. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umezawa K, Ikeda Y, Kawase O, Naganawa H, Kondo S. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 2001;13:1550–1553. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuda DS, Mynderse JS, Baker PJ, Berry DM, Boeck LD, et al. J Antibiot. 1990;6:623–633. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.623. For a structurally related compound see Gomi S, Ohuchi S, Sasaki T, Itoh J, Sezaki M. J Antibiot. 1987;6:740–749. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.740.

- 22.While 11-deschloro-5 has not been identified as a natural product, there are several naphthopyranone derivatives known.

- 23.Gould SJ, Melville CR, Cone MR, Chen J, Carney JR. J Org Chem. 1997;62:320–324. doi: 10.1021/jo961486y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decarboxylations of aromatic ring systems such as 10 are known in synthetic chemistry to occur with gentle heating. Moody CJ, Rees CW, Tsoi SC. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1984;5:915–920.Dostal W, Heinisch G. J Heterocyclic Chem. 1985;22:1543–1546.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.