Abstract

The complex spatio-temporal patterns of development and anatomy of nervous systems play a key role in our understanding of arthropod evolution. However, the degree of resolution of neural processes is not always detailed enough to claim homology between arthropod groups. One example is neural precursors and their progeny in crustaceans and insects. Pioneer neurons of crustaceans and insects show some similarities that indicate homology. In contrast, the differentiation of insect and crustacean neuroblasts (NBs) shows profound differences and their homology is controversial. For Drosophila and grasshoppers, the complete lineage of several NBs up to formation of pioneer neurons is known. Apart from data on median NBs no comparable results exist for Crustacea. Accordingly, it is not clear where the crustacean pioneer neurons come from and whether there are NBs lateral to the midline homologous to those of insects. To fill this gap, individual NBs in the ventral neuroectoderm of the crustacean Orchestia cavimana were labelled in vivo with a fluorescent dye. A partial neuroblast map was established and for the first time lineages from individual NBs to identified pioneer neurons were established in a crustacean. Our data strongly suggest homology of NBs and their lineages, providing further evidence for a close insect–crustacean relationship.

Keywords: Drosophila, evolution, arthropods, neurogenesis, cell lineage

1. Introduction

Despite the overall similarities of the central nervous system (CNS) between the major arthropod groups, its early development shows some distinct differences at the cellular level. In myriapods and chelicerates, clusters of neural precursors immigrate from the ventral neuroectoderm and differentiate directly into neurons or glia cells to form the ventral CNS (figure 1; Stollewerk et al. 2001; Mittmann 2002; Stollewerk & Chipman 2006). In contrast, insects and crustaceans form their ventral CNS via neuroblasts (NBs), large neural precursor cells dividing in an asymmetrical stem cell mode to produce columns of ganglion mother cells (GMCs). At least in insects, each GMC in turn divides once to generate ganglion cells (GCs) that differentiate into neurons and/or glia cells (figure 1; insects: Wheeler 1891, Bate 1976, Doe & Goodman 1985, Hartenstein et al. 1987, Truman & Ball 1998; crustaceans: McMurrich 1895, Dohle 1976, Scholtz 1992, Gerberding 1997, Harzsch 2001).

Figure 1.

Modes of neurogenesis in euarthropods. In chelicerates and myriapods, neurons are generated via immigration of post-mitotic neural precursor cells (np), whereas in insects and crustaceans we find specialized cells, NBs, which divide in a stem cell-like manner. In insects, they bud off smaller GMCs which subsequently divide only once to generate GCs that differentiate into neurons and glia cells. There are indications for such a division pattern in higher crustaceans, but direct evidence is still missing. e, ectoderm.

In 1984, Thomas et al. (1984) detected a set of early differentiating neurons, responsible for pioneering major axon pathways in the embryonic CNS of insects and crustaceans, which led them to propose a common plan for neurogenesis in arthropods. A series of subsequent studies at the level of individually identified neurons including position, axon morphology and timing of outgrowth confirmed the existence of a set of homologous pioneer neurons in insects and crustaceans that finds no counterpart in myriapods (Whitington et al. 1991, 1993, 1996). Together with molecular datasets (e.g. Boore et al. 1998; Shultz & Regier 2000; Friedrich & Tautz 2001; Giribet et al. 2001; Kusche et al. 2002; Pisani et al. 2004; Petrov & Vladychenskaya 2005; Regier et al. 2005; Mallatt & Giribet 2006), these studies contributed considerably to the new discussion on arthropod relationships (e.g. Whitington & Bacon 1997; Dohle 2001; Richter 2002; Whitington 2004; Giribet et al. 2005).

Furthermore, Gerberding & Scholtz (1999, 2001) identified a midline NB that shows some similarities to corresponding cells in insects. Astonishingly, it remained controversial whether NBs in crustaceans are homologous to those in insects (convergent: Dohle & Scholtz 1988, Scholtz 1992; question unresolved: Whitington 1996, Dohle 2001, Scholtz & Gerberding 2002, Harzsch 2003; homologous: Duman-Scheel & Patel 1999, Richter 2002, Harzsch 2006). This is due to some distinct differences concerning the way they are generated and their final position in relation to the ventral neuroectoderm. However, in contrast to the insect situation, in no case has the lineage from individual NBs to identified pioneer neurons been traced in a crustacean species. To fill this gap, we used for the first time an in vivo labelling technique with the lipophilic fluorescent dye DiI in combination with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction to study NBs in the ventral neuroectoderm of a higher crustacean. The amphipod crustacean Orchestia cavimana was chosen owing to its excellent qualities for single-cell labelling studies (e.g. Gerberding & Scholtz 1999, 2001; Wolff & Scholtz 2002, 2006).

2. Material and methods

Specimens of the semi-terrestrial amphipod species O. cavimana were collected on the lakefront of the Tegeler See (Berlin). The animals were reared in a terrarium at 18–20°C and fed with carrots, cucumbers and oatmeal. Eggs in relevant stages were isolated from the ventral brood pouch (marsupium) of the females by flushing out with a glass pipette. Eggs were transferred to a saline solution that mimics the osmotic milieu in the marsupium (for details see Wolff & Scholtz 2002).

(a) In vivo labelling

In vivo cell labelling was done with an inverse microscope equipped with a micromanipulator (Leica DMIRB). Eggs in relevant stages were mounted on microscopic slides under small cover-slips that were equipped with plasticine feet at the corners. Positioning of the eggs was carried out by carefully shifting the cover-slip. Injection needles were made by pulling (KOPF Puller 720) glass pipettes (Hilsberg, diameter 1.0 mm, thickness 0.2 mm). After pulling, the tips of the needles were sharpened with a horizontal grinder (Bachofer) the angle of the cutting edge varying between 20° and 30°.

The fluorescent marker DiI (Molecular Probes) was used as a vital marker (2 mg ml−1 dissolved in soy oil). It is lipophilic and intercalates in the cell membrane, which guarantees that the dye is exclusively restricted to the daughter cells. In-vivo-labelled eggs were singly kept in Petri dishes at 16°C in the saline mentioned above, which was changed every second day. Labelled eggs were checked and documented regularly with a fluorescence-microscope (Zeiss Axiophot1) equipped with digital camera (Nikon D1) using blue light or green light (strongest excitation of DiI).

(b) CLSM and three-dimensional reconstruction

For fixation and documentation with the laser scanning microscope (Leica SP2), embryos were dissected in PBS-buffered 4% formaldehyde solution, counterstained with a nucleic specific dye (Hoechst) and mounted in the anti-bleaching detergent DABCO–Glycerol (25 mg DABCO (1,4 diazabicyclol-2,2,2-octane, Merck) in 1 ml PBS to 9 ml glycerol). The image stacks produced by the laser scanning microscope were analysed with the software Imaris v. 5.0.1 (Bitplane AG), which allows a three-dimensional reconstruction of the counter-stained cells and the clones of the in vivo-labelled cells. The feature ‘Volume’ in the program module ‘Surpass’ creates a three-dimensional object that can be magnified and moved in all directions.

3. Results and discussion

As in all higher crustaceans studied in this respect, in Orchestia the NBs of the post-naupliar germ band are generated via a stereotyped cell division pattern starting with the formation of regular transverse cell rows in the ventral ectoderm before the onset of morphogenesis (figure 2a). NBs arise continuously in the two initial cell columns adjacent to the midline whereas the more lateral cells form limbs and tergites (figure 2a,b; Dohle 1976; Dohle & Scholtz 1988; Scholtz 1990, 1992). During neurogenesis, the NBs remain at the embryo's surface intermingled with ectoderm cells. Previous studies using histological nuclear staining identified approximately 12 individual NBs within this pattern (Dohle 1976; Scholtz 1990).

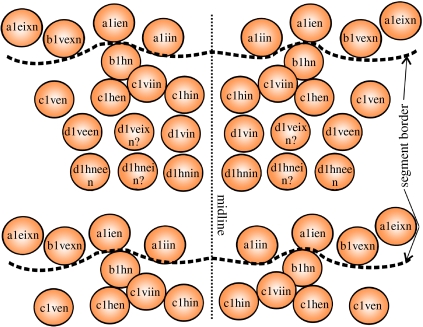

Figure 2.

Invariant cell lineages in the ventral ectoderm in O. cavimana. (a) Scheme (modified after Wolff & Scholtz 2006) of the cell division pattern in the post-naupliar ectoderm characteristic for malacostracan crustaceans. The designation of the cells arising within the stereotyped cell division pattern in the post-naupliar germ band of O. cavimana follows Scholtz (1990). Each of the transverse ectodermal rows (row abcd) which form at a stage of approximately 400 cells represents a genealogical unit and undergoes the same division pattern. First, it undergoes two mitotic waves with longitudinal spindle directions resulting in a grid-like pattern of four rows (a, b, c, d). With the subsequent differential cleavages, morphogenesis starts. Within the cell columns 0 (midline) to 2, the ganglion anlagen are formed, whereas the more lateral columns give rise to the limb anlagen (orange line marks border between ganglion anlagen and limb anlagen). b1hn and d1hn (marked in red) represent the first NBs arising from the stereotyped cell divisions of the initial ectodermal rows. During each differential cleavage, new NBs are added, the NBs themselves being able to switch to the production of ectodermal cells and back to the production of GMCs. The segmental border does not match the genealogical border. The segmental border runs between the descendants of row b (black dotted line). The present study focuses on the cells of column 1 which were labelled mainly after the second mitotic wave (a1, b1, c1 and d1). After the differential cleavages, labelling is hindered by the small size of the cells. (b) Detail of two thoracic segments during the differential cleavages (SEM image). The midline (0) and cell columns 1 and 2 which give rise to the ventral ganglia are marked in orange. The first two NBs arising during the differential cleavages in cell column 1 are marked in red (b1hn and d1hn).

The labelling of cells of the column adjacent to the midline allowed the identification of an additional 4–6 NBs per hemisegment, and we established a partial NB map (figure 3). Although we did not test it directly, there is some evidence that the second cell column next to the midline generates a similar number of NBs. Accordingly, we suggest a number of 26–30 NBs per hemisegment. This figure corresponds to that inferred for decapod crustaceans (Scholtz 1992) and in insects where 29–31 NBs are differentiated in each thoracic hemisegment (Bate 1976; Tamarelle et al. 1985; Hartenstein et al. 1987; Doe 1992; Truman & Ball 1998). In contrast to crustacean NBs, those of insects detach from the neuroectoderm early in embryogenesis, forming a layer between ectoderm and mesoderm (figure 1; Bate 1976; Tamarelle et al. 1985; Hartenstein et al. 1987; Dohle & Scholtz 1988; Doe 1992; Truman & Ball 1998).

Figure 3.

Neuroblast map of a generalized thoracic segment in Orchestia. From the cells of column 1 of the grid-like pattern in the post-naupliar ectoderm of Orchestia, 13–15 NBs arise.

To date, it has not been proven that crustacean GMCs show the same further fate as those of insects. Here we can definitely show that the division pattern of Orchestia GMCs corresponds in great detail with that in insects. The NBs in Orchestia produce smaller GMCs into the interior of the ganglion anlage which divide only once to give rise to neurons and/or glia cells (figure 4a–c). As in insects (Goodman & Doe 1993), the first GMC starts its division after three GMCs have been generated by the NB, and the first GCs start their differentiation when three of the GMCs have divided (figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Early neuroblast divisions in the thoracic segments of Orchestia. Anterior is to the top and median to the right. (a) DiI labelling of the cell d1v (red) with nucleic specific Hoechst counterstain (blue); stage 2 (staging according to Ungerer & Wolff 2005). Three-dimensional reconstruction (posteroventral view on the ganglion anlagen) with Imaris (Surpass mode). To better visualize labelled cells, their nuclei are marked with orange balls. The NBs d1vin and d1veen arise from the cell d1v and produce smaller GMCs (asterisks) into the interior of the ganglion anlage. It is very probable that d1vei or one of its descendants (d1veixn) represents a neuroblast, although the assignment of GMCs was not always possible without doubt due to the close spatial relation of cells. (b) DiI labelling of a1 in stage 3 of Orchestia development. Digital frontal section through the ganglion anlage (Imaris) showing the three NBs in the a1 lineage and their descendants which enter dorsomedially into the ganglion anlage. (c) Same labelling and CLSM image stack as in (b) with three-dimensional visualization of cells by setting a ball in each cell in Imaris. White arrows point to the border of GMCs (asterisks) and GCs. After three GMCs have been produced, the first starts to divide resulting in two GCs. Again, after three divisions of GMCs, the first GCs start to differentiate into neurons (black arrow points to first axon of the neuroblast alien) or glia cells (not shown).

To test whether NBs can be identified in crustaceans which are individually homologous to those in insects, we labelled single NB precursor cells to trace their lineage up to the differentiation of pioneer neurons (a1: n=27, b1: n=31, c1: n=37, d1: n=38; see figure 2). Since the NB 1–1 of insects is well characterized by its position and by the pattern of pioneer neurons produced by it, we looked for a corresponding NB in Orchestia. Indeed, we identified the NB b1hn as sharing many characteristics with the NB 1–1 of insects (figure 5). As is the case for the latter (Goodman et al. 1984; Goodman & Doe 1993; Udolph et al. 1993; Broadus et al. 1995; Bossing et al. 1996; Schmid et al. 1999), the first GMC of Orchestia gives rise to the neurons aCC and pCC, whose early outgrowing axons act as pioneers for the establishment of the intersegmental nerve and the connective, respectively (figure 5c–f,h). In addition, the first GMCs of 1–1 in insects (Goodman & Doe 1993) and b1hn in Orchestia are generated in the anteriormost region of the segment and migrate anteriorly across the intersegmental border into the adjacent ganglion anlage (figure 5d). Both aCC and pCC end up in a position in the dorsalmost layer of the ganglion anlage behind the commissures and medial to the connective (figure 5e,f,h). As the insect NB 1–1 (Doe 1992; Broadus & Doe 1995), b1hn of Orchestia is the first NB in the segment close to the midline lying behind two rows of en positive NBs (figure 5a,g).

Figure 5.

Comparison of b1hn in Orchestia and 1–1 in insects. (a) Neuroblast map of thoracic segment in Orchestia, b1hn is marked red. d1hnin (yellow) and a1iin (light grey) are NBs which also have putatively homologous counterparts in insects. Grey-shaded NBs are engrailed positive (according to Scholtz et al. 1993). (b) DiI labelling of b1 (excited with blue light instead of green light to avoid early bleaching). After the second mitotic wave, one of the first NBs appears in the descendants of the cell column 1, b1hn. Anterior is to the top. (c) Clone of b1 in stage 3 of Orchestia. Anterior is to the top, median to the right. The first GMC of the neuroblast b1hn migrates medially and the resulting GCs are the first to differentiate. (d) Clone of b1 in stage 3–4 of Orchestia. Anterior is to the top, median to the left. The first GMCs of the neuroblast b1hn have migrated into the anteriorly adjacent ganglion anlage and the early outgrowing axon of pCC is visible. (e,f) Clone of b1 at late stage 4 of Orchestia, dorsal view. (e) Schematic reconstruction. (f) Imaris Surpass mode. The clone of b1 contributes cells to two adjacent ganglia. The sibling neurons aCC and pCC lie in the dorsalmost layer of the ganglion in the angle between posterior commissure (pc) and connective. aCC is a motoneuron leaving the CNS via the intersegmental nerve whereas pCC is an interneuron sending an axon anteriorly along the ipsilateral connective. Black asterisks in the scheme mark clusters of not individually identified neurons and/or glia cells with their axons being marked in green. Dotted line represents segment border. (g) Drosophila neuroblast map (modified after Doe 1992). The neuroblast 1–1 is marked red; 4–2 (yellow) and 7–1 (light grey) are NBs which also have putatively homologous counterparts in Orchestia. Grey-shaded NBs are engrailed positive. Dotted line represents segment border. (h) Clone of 1–1 (after Bossing et al. 1996). The progeny of 1–1 is distributed between two adjacent ganglia, as is the clone of b1hn. The sibling neurons aCC and pCC also lie in the dorsalmost layer of the ganglion in the angle between pc and connective.

A second candidate was the NB 4–2 of Drosophila (figure 5g), again based on its position and its characteristic offspring, the pioneer neuron RP2 (Bossing et al. 1996; Landgraf et al. 1997; Schmid et al. 1999; figure 6b). We found that the NB d1hnin of Orchestia shares the medial position in the anteroposterior axis (figure 5a) and among others the production of the well-identifiable pioneer neuron RP2 (figure 6a). However, NB 4–2 lies in the second column next to the midline whereas NB d1hnin is situated directly adjacent to the midline, so a positional shift would have to be assumed.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Orchestia and Drosophila NBs. (a) Clone of d1 (red) in a thoracic ganglion counterstained with Hoechst (blue; Imaris, Surpass mode). The clone of d1 comprises among others the lineage of d1hnin, the first GMC of which produces a neuron corresponding in position and axon morphology the RP2 neuron of Drosophila (figure 6b). It lies in the dorsalmost layer of the CNS between ac and pc (white star) and sends an axon anteriorly in the connective and into the intersegmental nerve (white arrowheads). (b) Neuroblast 4–2 of Drosophila (after Bossing et al. 1996). The motoneuron RP2 lies in the dorsalmost layer of the ganglion and sends an axon into the intersegmental nerve (red open arrowheads). (c) Clone of a1 (red) in a thoracic ganglion (Imaris, Surpass mode). The posterior- and medianmost neurons of the clone of a1 (white star) are produced by the neuroblast a1iin (see also figure 4c). They are large neurons lying in a dorsal layer of the CNS with putatively homologous axon pathways as the U motoneurons in Drosophila (figure 6d) into the ipsilateral intersegmental nerve. (d) Neuroblast 7–1 of Drosophila (after Bossing et al. 1996). The U neurons are large motoneurons occupying a position ventromedial to the aCC and pCC neurons (figure 5h) sending their axons into the ipsilateral intersegmental nerve.

Likewise, the en positive NBs a1iin of Orchestia (figure 5a) and 7–1 of Drosophila (figure 5g) sharing a corresponding position at the posterior border of the segment close to the midline are putatively homologous. Although it was not possible to identify the entire lineage of a1iin, it is highly probable that it produces motoneurons sharing the characteristics of the U neurons produced by NB 7–1 of Drosophila (Bossing et al. 1996; Landgraf et al. 1997; Schmid et al. 1999; figure 6b,c).

Taken together, the position, the consistent mode of division, the correspondence of the NB cell lineages and their outcome in terms of identified neurons strongly suggest homology of some NBs in Orchestia and insects. Owing to the stereotyped cell division pattern characteristic for higher crustaceans (malacostracans; Dohle et al. 2004), it is likely that the aspects of neurogenesis investigated in Orchestia might be generalized for malacostracan crustaceans. Unfortunately, we do not know much about neurogenesis in non-malacostracan crustaceans. There are reports about NBs in some branchiopods showing that these remain at the surface as in malacostracan crustaceans (Gerberding 1997; Harzsch 2001; Wheeler & Skeath 2005), but no direct evidence for their division in a stem cell mode and no data about pioneer neurons yet exist. Corresponding data for the remaining crustaceans are completely lacking.

Based on molecular and morphological data, there is increasing evidence for a close relationship of insects and crustaceans forming the taxon Tetraconata (e.g. Dohle 1997, 2001; Zrzavý & Stýs 1997; Boore et al. 1998; Friedrich & Tautz 2001; Giribet et al. 2001, 2005; Regier & Shultz 2001; Kusche et al. 2002; Richter 2002; Pisani et al. 2004; Petrov & Vladychenskaya 2005; Regier et al. 2005; Harzsch 2006; Mallatt & Giribet 2006), with the Crustacea sometimes paraphyletic (e.g. Friedrich & Tautz 2001; Hwang et al. 2001; Regier & Shultz 2001; Regier et al. 2005; Harzsch 2006; Mallatt & Giribet 2006).

Preliminary investigations in onychophorans (Eriksson et al. 2003; Whitington 2006) and tardigrades (Hejnol & Schnabel 2005) did not indicate the existence of NBs but suggest that the nervous system is formed by immigration of neural precursors in these groups. This resembles to a certain extent the situation found in chelicerates and myriapods (Stollewerk et al. 2001; Mittmann 2002; Stollewerk & Chipman 2006). Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that immigration of neural precursors represents the ancestral state within arthropods, and the formation of NBs in insects and crustaceans in the derived state, thus providing additional support for the Tetraconata. However, even then we are still left with the question of the position of the NBs either in a layer between ectoderm and mesoderm as in insects or in the ectodermal layer as in crustaceans.

Some of the molecular mechanisms underlying the neurogenesis in representatives of insects (Cabrera et al. 1987; Romani et al. 1987; Skeath et al. 1992; Wheeler et al. 2003), chelicerates (Stollewerk et al. 2001; Stollewerk 2002) and myriapods (Dove & Stollewerk 2003; Kadner & Stollewerk 2004) have been revealed. It has been shown that corresponding mechanisms are responsible for generation of neural precursor cells in all three groups. From clusters of cells expressing proneural genes (e.g. achaete, scute) in the ventral neuroectoderm either groups of neural precursor cells (as seen in chelicerates and myriapods) or single cells (as seen in insects) are selected by lateral inhibition mediated by the transmembrane proteins Notch and Delta and translocated into the interior of the embryo (Simpson 1990; Seugnet et al. 1997). So far, corresponding data on crustaceans are almost completely lacking. A single study in the branchiopod, Triops longicaudatus, suggests a role of achaete–scute genes comparable to that in insects (Wheeler & Skeath 2005).

We propose that the translocation of neural precursors beneath the ectoderm in insects via lateral inhibition represents the plesiomorphic character state for the Tetraconata. In crustaceans, this mechanism must have changed in a way that allows the NBs to remain at the surface and to differentiate adjacent to each other in high density. If the preliminary data about superficial NBs in non-malacostracan crustaceans can be substantiated, then this would argue for monophyletic Crustacea, or at least a clade that minimally includes branchiopods and malacostracans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Edgecombe for improving the English and comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We are grateful to the plant physiology section at the Humboldt University for help with the CLSM. The study was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to G.S.

References

- Bate C.M. Embryogenesis of an insect nervous system I. A map of the thoracic and abdominal neuroblasts in Locusta migratoria. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1976;35:107–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boore J.L, Lavrov D.V, Brown W.M. Gene translocation links insects and crustaceans. Nature. 1998;392:667–668. doi: 10.1038/33577. doi:10.1038/33577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossing T, Udolph G, Doe C.Q, Technau G.M. The embryonic central nervous system lineages of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Neuroblast lineages derived from the ventral half of the neurectoderm. Dev. Biol. 1996;179:41–64. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0240. doi:10.1006/dbio.1996.0240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadus J, Doe C.Q. Evolution of neuroblast identity: seven-up and prospero expression reveal homologous and divergent neuroblast fates in Drosophila and Schistocerca. Development. 1995;121:3989–3996. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadus J, Skeath J.B, Spana E.P, Bossing T, Technau G.M, Doe C.Q. New neuroblast markers and the origin of the aCC/pCC neurons in the Drosophila central nervous system. Mech. Dev. 1995;53:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00454-8. doi:10.1016/0925-4773(95)00454-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera C.V, Martinez-Arias A, Bate M. The expression of three members of the achaete–scute gene complex correlates with neuroblast segregation in Drosophila. Cell. 1987;50:425–433. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90496-x. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90496-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe C.Q. Molecular markers for identified neuroblasts and ganglion mother cells in the Drosophila central nervous system. Development. 1992;116:855–863. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe C.Q, Goodman C. Early events in insect neurogenesis. I. Development and segmental differences in the pattern of neuronal precursor cells. Dev. Biol. 1985;111:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90445-2. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(85)90445-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohle W. Die Bildung und Differenzierung des postnauplialen Keimstreifs von Diastylis rathkei. (Crustacea, Cumacea) Zoomorphologie. 1976;84:235–277. doi:10.1007/BF01578696 [Google Scholar]

- Dohle W. Myriapod–insect relationships as opposed to an insect–crustacean sister group relationship. In: Fortey R.A, Thomas R.H, editors. Arthropod relationships. Chapman & Hall; London, UK: 1997. pp. 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Dohle W. Are the insects terrestrial crustaceans? A discussion of some new facts and arguments and the proposal of the proper name “Tetraconata” for the monophyletic unit Crustacea+Hexapoda. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 2001;37:85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dohle W, Scholtz G. Clonal analysis of the crustacean segment: the discordance between genealogical and segmental borders. Development. 1988;104(Suppl.):147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dohle W, Gerberding M, Hejnol A, Scholtz G. Cell lineage, segment differentiation, and gene expression in Crustaceans. In: Scholtz G, editor. Evolutionary developmental biology of Crustacea. A. A. Balkema; Lisse, The Netherlands: 2004. pp. 95–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dove H, Stollewerk A. Comparative analysis of neurogenesis in the myriapod Glomeris marginata (Diplopoda) suggests more similarities to chelicerates than to insects. Development. 2003;130:2161–2171. doi: 10.1242/dev.00442. doi:10.1242/dev.00442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman-Scheel M, Patel N.H. Analysis of molecular marker expression reveals neuronal homology in distantly related arthropods. Development. 1999;126:2327–2334. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B.J, Tait N.N, Budd G.E. Head development in the onychophoran Euperipatoides kanangrensis with particular reference to the central nervous system. J. Morphol. 2003;255:1–23. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10034. doi:10.1002/jmor.10034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich M, Tautz D. Arthropod rDNA phylogeny revisited: a consistency analysis using Monte Carlo simulation. Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 2001;37:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gerberding M. Germ band formation and early neurogenesis of Leptodora kindtii (Cladocera): first evidence for neuroblasts in the entomostracan crustaceans. Inv. Repr. Dev. 1997;32:63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gerberding M, Scholtz G. Cell lineage of the midline cells in the amphipod crustacean Orchestia cavimana (Crustacea, Malacostraca) during formation and separation of the germ band. Dev. Genes. Evol. 1999;209:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s004270050231. doi:10.1007/s004270050231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerberding M, Scholtz G. Neurons and glia in the midline of the higher crustacean Orchestia cavimana are generated via an invariant cell lineage that comprises a median neuroblast and glial progenitors. Dev. Biol. 2001;235:397–409. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0302. doi:10.1006/dbio.2001.0302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G, Edgecombe G.D, Wheeler C.W. Arthropod phylogeny based on eight molecular loci and morphology. Nature. 2001;413:121–122. doi: 10.1038/35093097. doi:10.1038/35093097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet, G., Richter, S., Edgecombe, G. D. & Wheeler, C. W. 2005 The position of crustaceans within Arthropoda—evidence from nine molecular loci and morphology. In Crustacea and arthropod relationships (eds S. Koenemann & R. Jenner). Crustacean Issues vol.16, pp. 307–352. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Goodman C.S, Doe C.Q. Embryonic development of the Drosophila central nervous system. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York, NY: 1993. pp. 1131–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C.S, Bastiani M.J, Doe C.Q, duLac S, Helfand S.L, Kuwada J.Y, Thomas J.B. Cell recognition during neuronal development. Science. 1984;225:1271–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.6474176. doi:10.1126/science.6474176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V, Rudloff E, Campos-Ortega J.A. The pattern of proliferation of the neuroblasts in the wild-type embryo of Drosophila melanogaster. Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 1987;196:473–485. doi: 10.1007/BF00399871. doi:10.1007/BF00399871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzsch S. Neurogenesis in the crustacean ventral nerve chord: homology of neuronal stem cells in Malacostraca and Branchiopoda? Evol. Dev. 2001;3:154–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003154.x. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003154.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzsch S. Ontogeny of the ventral nerve cord in malacostracan crustaceans: a common plan for neuronal development in Crustacea, Hexapoda and other Arthropoda? Arthrop. Struct. Dev. 2003;32:17–37. doi: 10.1016/S1467-8039(03)00008-2. doi:10.1016/S1467-8039(03)00008-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzsch S. Architecture of the nervous system and a fresh view on arthropod phylogeny. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2006;2006:1–33. doi: 10.1093/icb/icj011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejnol A, Schnabel R. The eutardigrade Thulinia stephaniae has an indeterminate development and the potential to regulate early blastomere ablations. Development. 2005;132:1349–1361. doi: 10.1242/dev.01701. doi:10.1242/dev.01701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang U.W, Friedrich M, Tautz D, Park C.J, Kim W. Mitochondrial protein phylogeny joins myriapods with chelicerates. Nature. 2001;413:154–157. doi: 10.1038/35093090. doi:10.1038/35093090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadner D, Stollewerk A. Neurogenesis in the chilopod Lithobius forficatus suggests more similarities to chelicerates than to insects. Dev. Genes Evol. 2004;214:367–379. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0419-z. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0419-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusche K, Ruhberg H, Burmester T. A hemocyanin from the Onychophora and the emergence of respiratory proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10 545–10 548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152241199. doi:10.1073/pnas.152241199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf M, Bossing T, Technau G.M, Bate M. The origin, location and projections of the embryonic abdominal motorneurons of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:9642–9655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallatt J, Giribet G. Further use of nearly complete 285 and 185 rRNA genes to classify Ecdysozoa: 37 more arthropods and a kinorhynch. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006;40:772–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.04.021. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurrich J.P. Embryology of the isopod Crustacea. J. Morphol. 1895;11:63–154. doi:10.1002/jmor.1050110103 [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann B. Early neurogenesis in the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus and its implication for arthropod relationships. Biol. Bull. 2002;203:2221–2222. doi: 10.2307/1543407. doi:10.2307/1543407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov N.B, Vladychenskaya N.S. Phylogeny of molting protostomes (Ecdysozoa) as inferred from 18S and 28S rRNA gene sequence. Mol. Biol. 2005;39:503–513. doi:10.1007/s11008-005-0067-z [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani D, Poling L.L, Lyons-Weiler M, Hedges S.B. The colonization of land by animals: molecular phylogeny and divergence times among arthropods. BMC Biol. 2004;2:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-2-1. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-2-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier J.C, Shultz J.W. Elongation factor-2: a useful gene for arthropod phylogenetics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2001;20:136–148. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0956. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier J.C, Shultz J.W, Kambic R.E. Pancrustacean phylogeny: hexapods are terrestrial crustaceans and maxillopods are not monophyletic. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:395–401. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2917. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S. The Tetraconata concept: hexapod–crustacean relationships and the phylogeny of Crustacea. Org. Divers. Evol. 2002;2:217–237. doi:10.1078/1439-6092-00048 [Google Scholar]

- Romani S, Campuzano S, Modolell J. The achaete–scute complex is expressed in neurogenic regions of Drosophila embryos. EMBO J. 1987;6:2085–2092. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A, Chiba A, Doe C.Q. The embryonic central nervous system lineages of Drosophila melanogaster. II. Neuroblast lineages derived from the dorsal part of the neuroectoderm. Development. 1999;126:4653–4689. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz G. The formation, differentiation and segmentation of the post-naupliar germ band of the amphipod Gammarus pulex L. (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida) Proc. R. Soc. B. 1990;239:163–211. doi:10.1098/rspb.1990.0013 [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz G. Cell lineage studies in the crayfish Cherax destructor (Crustacea, Decapoda): germ band formation, segmentation, and early neurogenesis. Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 1992;202:36–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00364595. doi:10.1007/BF00364595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz G, Gerberding M. Cell lineage of crustacean neuroblasts. In: Wiese K, editor. The crustacean nervous system. Springer; Berlin, Germany; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 406–416. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz G, Dohle W, Sandeman R.E, Richter S. Expression of engrailed can be lost and regained in cells of one clone in crustacean embryos. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1993;37:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seugnet L, Simpson P, Haenlin M. Transcriptional regulation of Notch and Delta: requirement for neuroblast segregation in Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:2015–2025. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz J.W, Regier J.C. Phylogenetic analysis of arthropods using two nuclear protein-encoding genes supports a crustacean+hexapod clade. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2000;267:1011–1019. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1104. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. Lateral inhibition and the development of the adult sensory bristles of the peripheral nervous system of Drosophila. Development. 1990;109:509–519. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeath J.B, Panganiban G, Selegue J, Carroll S.B. Gene regulation in two dimensions: the proneural achaete and scute genes are controlled by combinations of axis patterning genes through a common intergenic control region. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2606–2619. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2606. doi:10.1101/gad.6.12b.2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollewerk A. Recruitment of cell groups through Delta/Notch signalling during spider neurogenesis. Development. 2002;129:5339–5348. doi: 10.1242/dev.00109. doi:10.1242/dev.00109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollewerk A, Chipman A. Neurogenesis in myriapods and chelicerates and its importance for understanding arthropod relationships. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2006;46:195–206. doi: 10.1093/icb/icj020. doi:10.1093/icb/icj020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollewerk A, Weller M, Tautz D. Neurogenesis in the spider: new insights from comparative analysis of morphological processes and gene expression patterns. Development. 2001;128:2673–2688. doi: 10.1016/S1467-8039(03)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamarelle M, Haget A, Ressouches A. Segregation, division, and early patterning of lateral thoracic neuroblasts in the embryo of Carausius morosus Br. (Phasmida: Lonchodidae) Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 1985;14:307–317. doi:10.1016/0020-7322(85)90045-5 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J.B, Bastiani M.J, Bate M, Goodman C.S. From grasshopper to Drosophila: a common plan for neuronal development. Nature. 1984;310:203–207. doi: 10.1038/310203a0. doi:10.1038/310203a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman J.W, Ball E.E. Patterns of embryonic neurogenesis in a primitive wingless insect, the silverfish, Ctenolepisma longicaudata: comparison with those seen in flying insects. Dev. Genes Evol. 1998;208:357–368. doi: 10.1007/s004270050192. doi:10.1007/s004270050192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udolph G, Prokop A, Bossing T, Technau G. A common precursor for glia and neurons in the embryonic CNS of Drosophila gives rise to segment specific lineage variants. Development. 1993;118:765–775. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerer P, Wolff C. External morphology of limb development in the amphipod Orchestia cavimana (Crustacea, Malacostraca, Peracarida) Zoomorphology. 2005;124:89–99. doi:10.1007/s00435-005-0114-2 [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler W.M. Neuroblasts in the arthropod embryo. J. Morphol. 1891;4:337–344. doi:10.1002/jmor.1050040305 [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S.R, Skeath J.B. The identification and expression of achaete–scute genes in the branchiopod crustacean Triops longicaudatus. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2005;5:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.005. doi:10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S, Carrico M, Wilson B, Brown S, Skeath J. The expression and function of the achaete–scute genes in Tribolium castaneum reveals conservation and variation in neural pattern formation and cell fate specification. Development. 2003;130:4373–4381. doi: 10.1242/dev.00646. doi:10.1242/dev.00646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M. Evolution of neural development in the arthropods. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996;7:605–614. doi:10.1006/scdb.1996.0074 [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M. The development of the crustacean nervous system. In: Scholtz G, editor. Evolutionary developmental biology of Crustacea. Crustacean issues. vol. 15. A. A. Balkema; Lisse, The Netherlands: 2004. pp. 135–167. [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M. The evolution of arthropod nervous systems: insights from neural development in the Onychophora and Myriapoda. In: Striedler G.F, Rubenstein J.L.R, Kaas J.H, editors. Theories, development, invertebrates. Academic Press; Oxford, UK: 2006. pp. 317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M, Bacon J.P. The organization and development of the arthropod ventral nerve cord: insights into arthropod relationships. In: Fortey R.A, Thomas R.H, editors. Arthropod relationships. Chapman and Hall; London, UK: 1997. pp. 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M, Meier T, King P. Segmentation, neurogenesis and formation of early axonal pathways in the centipede, Ethmostigmus rubripes. Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 1991;199:349–363. doi: 10.1007/BF01705928. doi:10.1007/BF01705928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M, Leach D, Sandeman R. Evolutionary change in neural development within the arthropods: axonogenesis in the embryos of two crustaceans. Development. 1993;118:449–461. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitington P.M, Harris K.-L, Leach D. Early axogenesis in the embryo of a primitive insect, the silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudata. Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 1996;205:272–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00365805. doi:10.1007/BF00365805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff C, Scholtz G. Cell lineage, axis formation, and the origin of germ layers in the amphipod crustacean Orchestia cavimana. Dev. Biol. 2002;250:44–58. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0789. doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff C, Scholtz G. Cell lineage analysis of the mandibular segment of the amphipod Orchestia cavimana reveals that the crustacean paragnaths are sternal outgrowths and not limbs. Front. Zool. 2006;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-3-19. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-3-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zrzavý J, Stýs P. The basic body plan of arthropods: insights from evolutionary morphology and developmental biology. J. Evol. Biol. 1997;10:353–367. doi:10.1007/s000360050029 [Google Scholar]