Abstract

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a recessive genetic disorder characterized by hypersensitivity to crosslinking agents that has been attributed to defects in DNA repair and/or replication. FANCD2 and the FA core complex bind to chromatin during DNA replication; however, the role of FA proteins during replication is unknown. Using Xenopus cell-free extracts, we show that FANCL depletion results in defective DNA replication restart following treatment with camptothecin, a drug that results in DSBs during DNA replication. This defect is more pronounced following treatment with mitomycin C, presumably because of an additional role of the FA pathway in DNA crosslink repair. Moreover, we show that binding of FA core complex proteins during DNA replication follows origin assembly and origin firing and is dependent on the binding of RPA to ssDNA while FANCD2 additionally requires ATR, consistent with FA proteins acting at replication forks. Together, our data suggest that FA proteins play a role in replication restart at collapsed replication forks.

Keywords: Fanconi anemia, Mitomycin C, Replication forks, Replication restart

1. Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by chromosomal instability and hypersensitivity to crosslinking agents, such as Mitomycin C (MMC) [1,2], diepoxybutane (DEB) [3], and cisplatin (CDDP) [4]. Thirteen FA genes that participate in the FA pathway have been cloned. A nuclear FA complex (FA core complex), including FANCA, -B, -C, -E, -F, -G, -L, FAAP100, FAAP24 and FANCM, forms the ubiquitin E3 ligase for FANCD2 and FANCI [5–11]. While FANCL is the catalytic component of the E3 ligase [9,12], each component of the FA core complex is required for FANCD2 and FANCI monoubiquitylation and the loss of any component results in the loss of FANCD2 and FANCI monoubiquitylation [6–9,13]. The monoubiquitylation of FANCD2 and FANCI is also co-dependent and the absence of or the mutation of the ubiquitylation site on either protein results in the abrogation of monoubiquitylation of the other protein [14]. Monoubiquitylated FANCD2 and FANCI assemble into foci with BRCA1, RAD51, FANCD1/BRCA2, FANCJ/BRIP1, and FANCN/PALB2 [8,15–20]. Defects in proteins acting downstream of the FANCI-FANCD2 complex (FANCD1, FANCJ, and FANCN) result in cells with hypersensitivity to crosslinking agents but show normal FANCD2 and FANCI monoubiquitylation [18,19,21–23].

The FA pathway is activated in response to a variety of DNA damaging agents, including UV light, ionizing irradiation (IR), hydroxyurea treatment and crosslinking agents [24]. Because of the higher sensitivity of FA cells to crosslinking agents, FA proteins are thought to play specific roles in the recognition and/or repair of lesions generated by crosslinking agents, including interstrand crosslinks (ICLs). However, how the FA pathway regulates these processes remains elusive. Treatment of FA cells with crosslinking agents enhances the accumulation of chromosomal rearrangements and triggers arrest in G2/M with 4N DNA content. The latter suggests that FA proteins play a role in the resolution of replication blocks resulting from crosslinking agents [25].

Consistent with playing a role in DNA replication, FANCD2 and core complex components FANCA and FANCF bind to chromatin during unperturbed replication in Xenopus cell-free extracts [26] and core complex components FANCA, FANCC, and FANCG bind to DNA during normal replication in mammalian cells [27]. Both DNA damage-dependent and -independent FA chromatin binding are inhibited by geminin, which sequesters Cdt1 and prevents pre-RC assembly, and are thus dependent on DNA replication [26,27], underscoring the role of FA protein recruitment to DNA during DNA replication in the activation of the FA pathway. However, FA proteins also bind to small synthetic DNA substrates in replication-incompetent cell-free extracts, pointing to a possible role in DNA repair, independently of DNA replication [28].

Assembly of the pre-replicative complex (pre-RC) at origins of replication starts with the binding of the origin recognition complex (ORC), followed by the Cdc6- and Cdt1-dependent loading of the minichromosome maintenance proteins (MCM2-7) – the replicative helicase. Next, Cdk2 and Cdc7 protein kinases are required for the activation of origins, as seen by the recruitment of Cdc45, GINS, and MCM10 proteins and subsequent origin unwinding. The single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) generated by origin unwinding is then coated by RPA. Finally, DNA polymerases are bound and bi-directional DNA replication takes place [29]. DNA replication forks are the sites of complex DNA transactions and many DNA intermediates form at replication forks. Replication fork progression can slow or stop at sites of secondary DNA structures or protein-DNA complexes or following inhibition of DNA polymerases [30]. Stalled replication forks are normally stabilized by checkpoint kinases [31–34] and failure to properly stabilize and/or restart stalled replication forks can lead to replication fork collapse and the generation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) [32]. Small compounds have been used to inhibit replication fork progression and to distinguish between stalled and collapsed replication forks. Aphidicolin (APH), an inhibitor of DNA polymerases, causes replication fork stalling. Camptothecin (CPT) inhibits DNA topoisomerase I (topoI) by binding to the topoI-DNA intermediate and preventing the religation reaction [35], thus generating DSBs upon collision of the replication fork with the lesion and subsequent replication fork collapse. MMC is a potent DNA crosslinking agent that also causes DSBs and replication fork collapse. In contrast to APH, which does not affect the stability of DNA polymerase ε (Pol ε) at the replication fork, treatments with CPT and MMC result in the unloading of Pol ε from DNA [36].

We examined the role of FA proteins in repair and replication restart after APH, CPT, and MMC treatments in Xenopus cell-free extracts. We find that in the absence of a functional FA pathway, restart of replication forks following MMC or CPT treatment was impaired. Notably, CPT treatment does not generate DNA crosslinks. The timing of recruitment of FA proteins to chromatin during DNA replication coincides with RPA loading and RPA is required for FA proteins loading, thus placing the FA complex at replication forks. Taken together, our results implicate the FA pathway in the restart of collapsed replication forks.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of Xenopus extracts

Cytosolic interphase Xenopus eggs extracts were prepared and tested as described by Shechter D et al. (2004).

2.2 Antibodies and Reagents

Anti-xFANCD2, -xFANCA, -xFANCG, and -xFANCF antibodies were generated as described by Sobeck et al (2006) and Stone et al (2007). Anti-MCM6 antibodies were generated as described by Ying et al. [38]. Anti-RPA p70 antibodies were a gift from P Jackson, anti-Polα antibodies were a gift from WM Michael and T Wang, and anti-ATR antibodies were a gift from V Costanzo. The xFANCL sequence was described previously [26]. An xFANCL-GST fusion protein was made by inserting the xFANCL sequence into the pDONR201 vector of the Gateway Cloning System (Invitrogen) and recombination reactions to produce the expression vector pDEST GST-xFANCL. Recombinant GST-xFANCL protein was purified with Glutathione-Sepharose A beads (GE) and both bead-bound GST-FANCL and denatured GST-FANCL were used to immunize rabbits.

2.3 Immunodepletions

Immunodepletions of cytosolic extracts were performed using anti-Polα, -RPA, -ATR, and -FANCL antibodies coupled to Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B beads (Amersham Biosciences). Two rounds of depletion were performed for anti-Polα, -RPA, and -ATR and one round of depletion was performed for anti-FANCL by incubation of extracts with bead-bound antibodies at 4°C for 30 min per round. Mock depletion was performed using rabbit IgG (Sigma) coupled to Protein A beads. Immunodepletions were monitored by Western blot analysis.

2.4 Replication Assay

Chromosomal templates for DNA replication were prepared from demembranated Xenopus sperm nuclei as described by Murray (1991) Cytosolic extracts were incubated with 1000 sperm nuclei/µL at 22°C with 1 µCi 32P-αdCTP for 90 min. The reaction was stopped with replication stop buffer (80 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.8, 8 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS), followed by incubation with proteinase K at 1mg/mL for 1 h at 60°C, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. DNA synthesis was monitored by the incorporation of 32P-αdCTP following agarose gel electrophoresis. Gels were exposed for autoradiography and quantified using a PhosphorImager. The entire lane (the DNA remaining in the well and the migrated DNA) was quantified.

2.5 Chromatin binding assay

For chromatin binding assays, cytosolic extracts were incubated with 2500 sperm nuclei/µL at 22°C. The reactions were incubated for the times indicated and each reaction was diluted with chromatin isolation (CI) buffer (100mM KCl, 2.5 MgCl2, 50 mM Hepes pH 7.8) supplemented with 0.125% Triton X-100. Chromatin was isolated through a 30% sucrose solution in CI buffer at 6000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The samples were run on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

3. Results

3.1 Chromatin binding of FA proteins requires origin activation and RPA recruitment

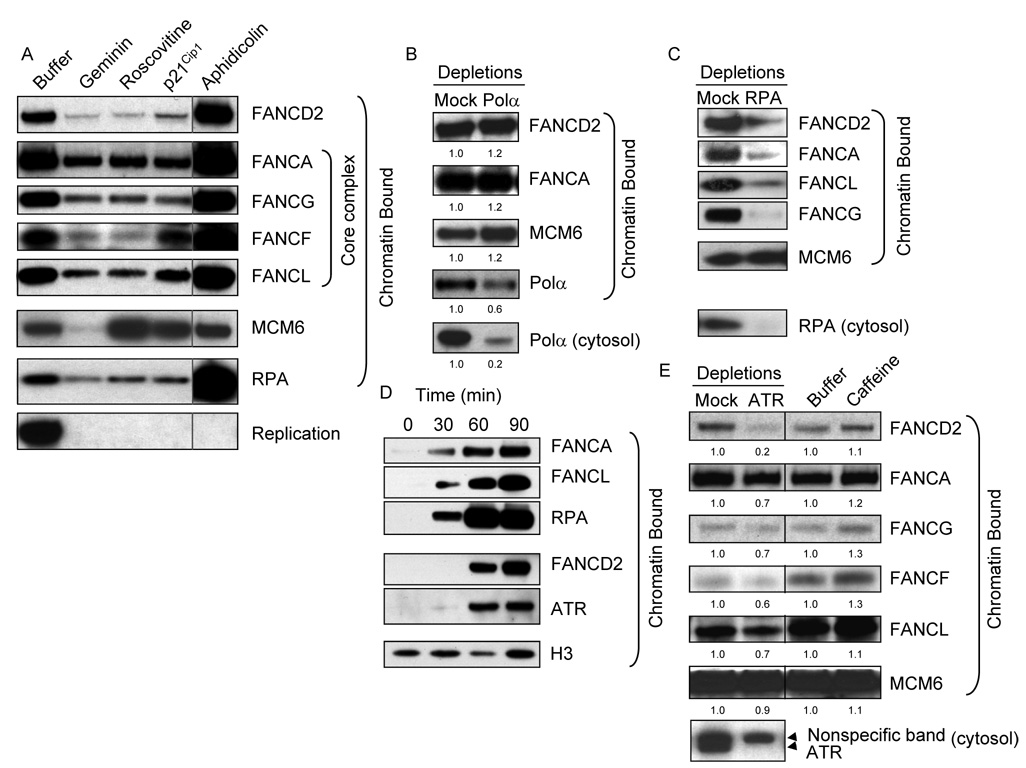

We have previously shown that FA proteins loading onto chromatin requires the assembly of the pre-replicative complex [26]. To gain further insight into the function(s) of FA proteins in DNA replication, we determined the requirements for FA protein binding to DNA. We supplemented Xenopus cytosolic extracts with geminin, roscovitine, p21CIP1, or APH to identify discrete steps required during DNA replication. Sperm nuclei were assembled and incubated in extracts for 60 min under these experimental conditions, purified from the cytosolic fractions and the association of FA proteins was probed by Western blot of the purified chromatin fraction (Figure 1A and Supplemental figure S1). The long and short forms of FANCD2, corresponding to FANCD2 with and without monoubiquitylation can be detected in the cytosol. In contrast, only the monoubiquitylated form of FANCD2 is present on chromatin, consistent with previous observations (Supplemental figure S2) [26,39]. We first confirmed that geminin reduced chromatin binding of FANCD2 and FA core complex proteins FANCA, FANCG, FANCF, and FANCL (Figure 1A and Sobeck et al. 2006). Roscovitine and p21CIP1 are Cdk2 inhibitors that inhibit origin activation. Both reduced the chromatin binding of FANCD2 and FA core complex proteins to the levels observed upon geminin treatment (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure S1). APH, an inhibitor of replicative DNA polymerases, did not inhibit the chromatin binding of FANCD2 or FA core complex components (Figure 1A). To assess whether polymerase α (Pol α) protein was required for FA chromatin recruitment, we depleted Pol α from extracts using a specific antibody [40]. Depletion of 80% of cytosolic Pol α protein, which resulted in 40% reduction of chromatin-bound Pol α, did not affect the chromatin binding of FA proteins (Figure 1B). From these experiments, we conclude that recruitment of FA proteins to chromatin requires pre-RC assembly and the activation of replication origins, but does not require DNA polymerase activity and complete Pol α recruitment.

Figure 1. FA chromatin binding follows origin firing and precedes polymerase loading.

(A) Chromatin binding of FA proteins. Cytosolic extracts were incubated with buffer, 50 ng/µL Geminin, 500 µM Roscovitine, 20 ng/µL p21Cip1, or 100 ng/µL APH, as indicated, for 10 min. Sperm nuclei were incubated with the extracts for 60 min and chromatin-bound proteins were isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with xFANCD2, xFANCA, xFANCG, xFANCF, xFANCL, xMCM6 and RPA p70 antibodies. Bottom panel: The extent of replication in these extracts was assessed by 32P-αdCTP incorporation into genomic DNA. (B) Sperm nuclei were incubated with mock- and Pol α-depleted extracts for 60 min and chromatin-bound proteins were isolated and analyzed. Bottom panel: Soluble Pol α was monitored by Western blot in mock- and Polα-depleted extracts. (C) Sperm nuclei were incubated with mock- or RPA-depleted cytosolic extracts for 60 min and chromatin-bound proteins were isolated and analyzed. Bottom panel: Mock- and RPA-depleted extracts were probed with RPA p70 antibody. (D) Sperm nuclei were incubated with cytosolic extracts for the times indicated in the presence of 100 ng/µL APH and 5 mM caffeine, and chromatin-bound proteins were isolated and analyzed. (E) Sperm nuclei were incubated in mock- or ATR-depleted cytosolic extracts (lanes 1 and 2) or in cytosolic extract supplemented with buffer or 5 mM caffeine (lanes 3 and 4) for 60 min. Chromatin-bound proteins were isolated and analyzed. Bottom panel: Mock- and ATR-depleted extracts were probed with ATR antibody. Where shown, quantification of bands was performed with ImageJ and normalized to values in mock (B and E left panel) or buffer-treated (E right panel) values.

DNA unwinding at origins results in the generation of ssDNA and the binding of RPA to ssDNA and is a prerequisite for DNA polymerase action. To examine if FA recruitment requires RPA recruitment, we compared FA chromatin binding in mock- and RPA-depleted cytosolic extracts. Depletion of RPA resulted in a considerable reduction of FA core complex and FANCD2 recruitment to chromatin (Figure 1C), and FA protein loading was partially rescued by addition of recombinant human RPA protein (Supplemental figure S3), establishing that FA chromatin recruitment requires RPA.

3.2 ATR plays a structural role in the chromatin recruitment of FANCD2

Our data indicate that the chromatin recruitment of FA proteins requires RPA association to ssDNA regions generated at replication forks. ssDNA-RPA intermediates are required for the binding and activation of ATRIP-ATR complexes [2]. ATR is activated following DNA replication stress [41,42] as well as during unperturbed DNA replication [43]. Next, we compared the kinetics of FA core complex proteins, FANCD2, RPA and ATR chromatin binding (Figure 1D and Supplemental figure S4). We observed that the recruitment of FA core complex proteins, FANCA and FANCL, preceded that of FANCD2. Notably, FA core complex binding to chromatin coincided with the recruitment of RPA, whereas, FANCD2 binding to chromatin was concomitant with ATR chromatin recruitment (Figure 1D). These data are consistent with RPA being required for the chromatin binding of FA proteins and further suggest that FANCD2 chromatin recruitment is mechanistically different and could involve ATR.

Next, we compared FA protein loading between mock- and ATR-depleted extracts. ATR-depletion led to a dramatic decrease in FANCD2 chromatin binding, while the chromatin binding of FA core complex components was not significantly affected (Figure 1E). Consistent with similar observations following ATRIP depletion [26], this result shows that association of an intact FA core complex to chromatin is insufficient for the recruitment of FANCD2 in the absence of ATR-ATRIP. ATR can phosphorylate FA core complex proteins – FANCA, FANCE, FANCG, and FANCM – and FANCD2, FANCI, and FANCN/PALB2 [10,44–48] and ATR-dependent phosphorylations are important for FA-mediated MMC resistance [44]. Next, we determined whether FANCD2 required ATR-dependent phosphorylations. We treated extracts with caffeine, an inhibitor of ATM and ATR kinase activity and found that inhibition of ATR enzymatic activity did not reduce the chromatin binding of FANCD2 or FA core complex proteins (Figure 1E), indicating that ATR plays a structural but not enzymatic role in the chromatin recruitment of FANCD2.

3.3 The FA pathway is required for the repair and replication restart of MMC-induced lesions

Our data suggest that FA core complex and FANCD2 are recruited to DNA at RPA-coated ssDNA regions generated at replication forks during unperturbed replication (Figure 1), further suggesting that FA proteins associate specifically with replication forks and raising the possibility that the FA pathway plays a role in DNA transactions at replication forks. We have previously shown that inactivation of the FA pathway does not inhibit the progression of DNA replication. However, replication in Xenopus extracts depleted of FA proteins leads to the accumulation of DSBs, suggesting that FA proteins are required for the processing of DNA lesions generated during DNA replication and/or the restart of replication forks [26].

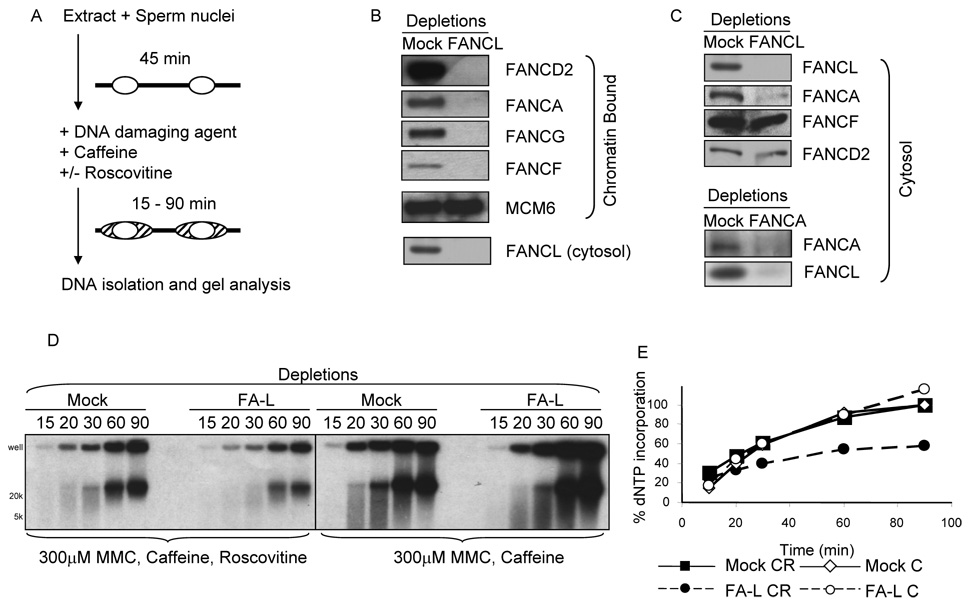

Cells derived from FA patients are hypersensitive to crosslinking agents such as MMC. Lesions generated by MMC are complex and include mono-adducts, intrastrand and interstrand crosslinks, which can all lead to the formation of nicks and subsequent DSBs during DNA replication. To examine the role of FA proteins in replication fork restart at drug-induced DNA lesions, we adapted a method from Trenz et al. (see scheme in Figure 2A). Cytosolic extract was incubated with sperm nuclei for 45 minutes to allow initiation but not completion of DNA replication. MMC was then added, causing DNA damage and subsequent replication fork collapse. The extract was supplemented with caffeine to inhibit ATM- and ATR-dependent checkpoints and roscovitine to prevent the firing of new origins. Replication fork restart was measured by radioactive nucleotide incorporation as DNA replication resumed at replication forks encountering damage. Depletion of FANCL from extracts inhibited the activation of the FA pathway and prevented the recruitment of FANCD2 to chromatin during DNA replication (Figure 2B), consistent with previous work [37]. Moreover, FA core complex proteins FANCA, FANCG, and FANCF also failed to associate with chromatin in FANCL-depleted extracts (Figure 2B), indicating that an intact FA core complex is required for the recruitment of these proteins to chromatin. Notably, depletion of FANCL resulted in the co-depletion of a significant fraction of FANCA and vice versa, whereas FANCD2 and FANCF protein levels were not reduced (Figure 2C), indicating that FANCL is in a complex with FANCA in Xenopus cytosolic extracts.

Figure 2. FANCL functions in MMC-induced lesion repair and replication restart.

(A) Scheme of the experimental design. Sperm nuclei are incubated with cytosolic extract for 45 min to allow DNA replication to start, shown as replication bubbles (right). At 45 min, a DNA damaging agent (300 µM MMC, 1 ng/µL APH, or 56 µM CPT) is added with 5 mM caffeine in the presence or absence of 500 µM roscovitine. The extent of replication restart is assessed by incorporation of 32P-αdCTP into genomic DNA of samples (dashed areas represent replication restart). (B) Sperm nuclei were incubated with mock- and FANCL-depleted extracts for 60 min and chromatin-bound proteins were isolated and analyzed. (C) Mock-, FANCL- and FANCA-depleted cytosolic extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. (D) Sperm nuclei were incubated in mock- and FANCL-depleted extracts as indicated in the scheme in 3A. 300µM MMC was added and replication restart was monitored by 32P-αdCTP incorporation for the times indicated. Chromatin was isolated and analyzed by agarose gel. (E) Lanes from the gel in 3D were quantified using a PhosphorImager. CR: Caffeine and Roscovitine, C: Caffeine

Cytosolic extracts depleted of FANCL showed a defect in the extent of nucleotide incorporation, i.e. replication restart, in the presence of MMC (Figure 2D–E, 3A). This defect was abrogated when roscovitine was omitted and new origins were allowed to fire (Figure 2D–E, Figure 3A). Since this decrease in nucleotide incorporation in the absence of FANCL is rescued by allowing the firing of new origins, this indicates that the defect is primarily due to the inability of replication forks to elongate past lesions caused by MMC. MMC generates a spectrum of DNA crosslinks and adducts. Therefore, the replication defect may be due to the inability of FANCL-depleted extract to repair lesions and/or the inability to stabilize or restart replication forks that encounter MMC-induced lesions. We attempted to rescue the FANCL-depleted extracts with recombinant FANCL protein. However, the addition of FANCL alone failed to rescue FANCD2 chromatin recruitment (Supplemental figure S5). This is not surprising since FANCL depletion results in the co-depletion of FANCA, which is itself in a complex with other FA core complex proteins such as FANCG (Stone et al. 2007 and Figure 2C), and it remains to be determined which other components of the FA core complex are also co-depleted with FANCL.

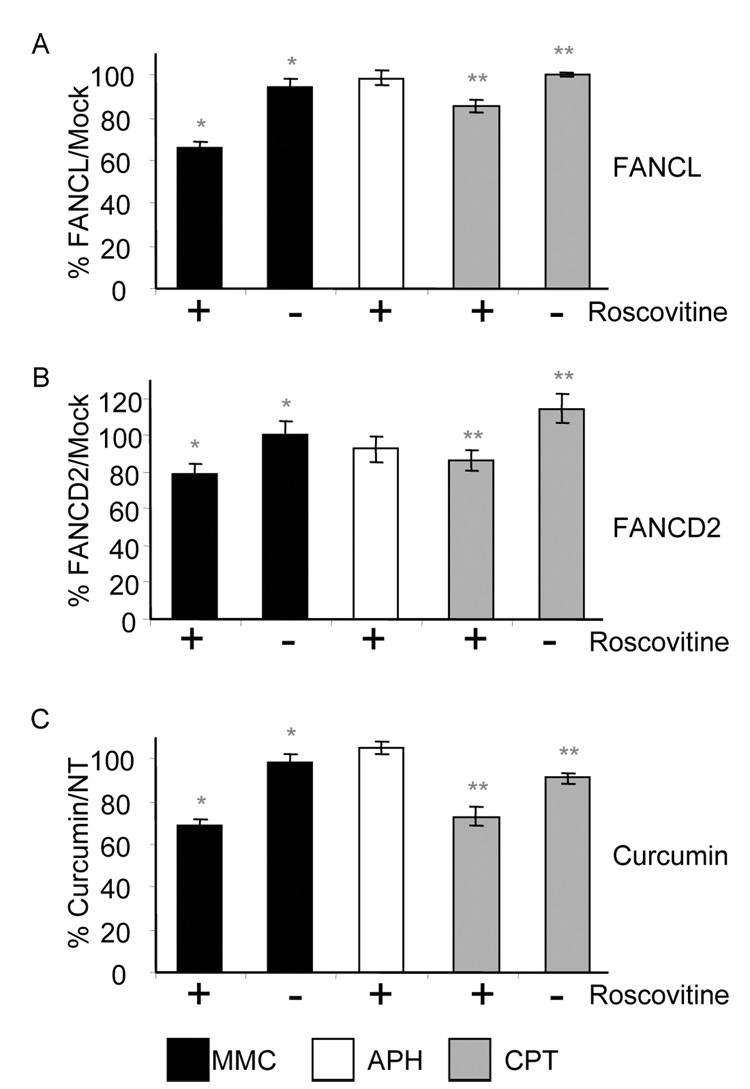

Figure 3. FANCL promotes the restart of collapsed but not stalled replication forks.

(A) Sperm nuclei were incubated in mock- or FANCL-depleted cytosolic extracts. 300 µM MMC (black bars), 40 µM APH (white bars), or 56 µM CPT (gray bars) were used in the replication restart, as indicated, with the addition of 5 mM caffeine, 32P-αdCTP, and with or without 500 µM Roscovitine (+ or −) for 90 min. Chromatin was isolated and analyzed by agarose gel and quantified as described above. Values from FANCL-depleted experiments were expressed as a percentage of the corresponding mock-depleted values. Each bar represents the average of at least 3 experiments – mean +/− SEM. * Statistically significant with p-value = 0.0007 ** Statistically significant with p-value = 0.0015 (B) As in 3A, with mock- or FANCD2-depleted cytosolic extracts. * Statistically significant with p-value = 0.0378 ** Statistically significant with p-value = 0.0123 (C) As in 3A, with extracts supplemented with buffer or 50 µM curcumin. * Statistically significant with p-value = 0.0011 ** Statistically significant with p-value = 0.0126

3.4 The FA pathway stabilizes collapsed but not stalled replication forks

To determine whether the defect in resuming DNA replication following MMC treatment was due to a deficiency of FANCL-depleted extracts in crosslink repair or a defect in replication fork stability, we examined replication restart in FANCL-depleted extracts supplemented with APH or CPT, treatments that do not generate DNA crosslinks. APH results in fork stalling due to DNA polymerase inhibition, and the stalled replisome remains chromatin-bound [36]. In contrast, CPT triggers replication-dependent DSBs which lead to replisome disassembly and replication fork collapse [36]. Replication restart of stalled forks induced by APH was not affected by FANCL depletion (Figure 3A). In contrast, FANCL-depleted extracts were deficient in the restart of collapsed replication forks caused by CPT addition (Figure 3A). Similar to MMC treatment, this deficiency was rescued by the firing of new origins when roscovitine was omitted (Figure 3A). These data show that FA proteins do not play a critical role in the restart of stalled replication forks and that FA proteins play a role in restarting collapsed replication forks at DSBs in the absence of DNA crosslinks. FANCL-depleted extracts had a stronger defect in the restart of MMC-induced lesions than that of CPT-induced lesions, suggesting that while FA proteins are facilitating the restart of forks at both types of lesions they could play an additional role in the repair of MMC-induced lesions.

To confirm that our findings are specific to inhibition of the FA pathway, we repeated the replication restart experiments in FANCD2-depleted extracts. We obtained similar results with FANCD2-depletion showing a reduction in replication restart with MMC and CPT but not with APH (Figure 3B and Supplemental figure S6). As with FANCL-depletion, the FANCD2 replication restart defect was rescued when roscovitine was omitted (Figure 3B). Finally, we conducted the replication restart experiments in the presence of curcumin, a small molecule inhibitor of the FA pathway that inhibits CDDP-induced FANCD2 monoubiquitylation in mammalian cells [49], and in Xenopus extracts (Landais et al, unpublished data). When 50µM curcumin was added to extracts treated with the DNA damaging agent, we observed a reduction in replication restart with MMC and CPT but not APH treatment and this reduction was abrogated when roscovitine was omitted (Figure 3C). The similarity between the phenotypes observed following FANCL and FANCD2 depletion and curcumin treatment strongly argues that the defect seen in replication restart of collapsed forks is specific to the FA pathway.

4. Discussion

FA cells are hypersensitive to crosslinking agents and mildly sensitive to CPT [50]. These agents generate a variety of DNA lesions that can physically block replication fork progression in the case of interstrand crosslinks (ICLs) or be converted into DNA breaks in the case of monoadducts or intrastrand crosslinks. The heterogeneity of the lesions has made it difficult to understand the mechanism(s) of this sensititvity.

By comparing the response to compounds generating different DNA lesions, we show that the absence of FA proteins leads to a defect in replication restart at collapsed replication forks but does not affect the restart of replication at stalled replication forks (Figure 2D–E, Figure 3A–C).This is consistent with studies from several groups supporting the idea that the FA pathway plays a critical role in the stability of replication forks. First, the FA pathway is activated in response to a variety of primary lesions that result in fork stalling and DSB formation [51]. Second, FA proteins are recruited to chromatin in a replication-dependent and damage-dependent manner [52]. Third, FA deficient cells and FA-depleted Xenopus extracts accumulate DNA damage during DNA replication [53]. Finally, the FA pathway interacts with BLM or with proteins associated with homologous recombination [47,54]. While collapsed replication fork restart requires FA proteins, it remains to be determined whether FA proteins participate in the prevention of fork collapse or the reassembly of collapsed forks.

This role of FA proteins at replication forks is supported by the observation that FA proteins assemble onto chromatin during unperturbed DNA replication in mammalian cells and Xenopus extract (Mi 2005, Sobeck 2006, this work). While the exact mechanism of FA recruitment to chromatin remains to be fully characterized, we show that FA chromatin recruitment requires pre-RC assembly, origin activation, and RPA binding to ssDNA at replication origins but not polymerase recruitment or activity (Figure 1A–C), suggesting that FA proteins are recruited to replication forks during unperturbed DNA replication. It is tempting to speculate that FA proteins are loaded directly via RPA. First, FA protein loading increases significantly in the presence of aphidicolin (Figure 1A), which increases ssDNA-RPA intermediates. Second, FANCJ was shown to directly bind to RPA [55]. While RPA at replication forks is sufficient for the recruitment of FA core complex components, it is not sufficient for FANCD2 recruitment to chromatin, which additionally requires ATR (Figure 1E). Our data indicating FANCD2 recruitment requires ATR and previous data showing FANCD2 recruitment requires ATRIP [26] demonstrate that the ATR-ATRIP complex is involved in the chromatin recruitment of FANCD2. Notably, ATR kinase activity is not required for the chromatin recruitment of FANCD2 since caffeine addition does not abolish FANCD2 recruitment (Figure 2D). Together, these data indicate that the ATR-ATRIP complex may act as a scaffold for FANCD2 chromatin binding. The specific requirement of ATR-ATRIP for FANCD2 chromatin association places FANCD2 at replication forks as they stall or slow down during DNA replication.

In summary, our study places the FA core complex and FANCD2 at the replication fork where they are poised to respond to both endogenous and exogenous sources of DNA damage. Surveying the progression of DNA replication, the FA core complex and the FANCD2/I complex can help stabilize replication forks that encounter damage and recruit DNA repair proteins, including FA downstream components – FANCD1/BRCA2, FANCJ/BRIP1, FANCN/PALB2, BRCA1, RAD51, and components of the BRAFT complex – including BLM, RPA, BLAP75 and DNA topoisomerase III α [56]. The role of FA proteins as guardians might be particularly important in the case of ICLs because these lesions not only require replication fork stabilization but a combination of repair processes. Indeed, translesion synthesis, nucleotide excision repair, and homologous recombination are likely to be required for the repair of a single ICL. Therefore, maintaining replication fork stability and coordinated activation of these repair pathways is essential. In the absence of FA proteins, replication forks encountering ICLs fail to be stabilized and repaired, leading to the generation of DSBs that can participate in illegitimate recombination and chromosomal rearrangements. The defective FA pathway found in FA patients can result in replication fork collapse and genomic instability that is responsible for predisposition to leukemias and squamous cell carcinomas observed in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. P Jackson, Dr. WM Michael, Dr. T Wang, and Dr. V Costanzo for anti-RPA p70, anti-Polα, and anti-ATR antibodies. We thank Dr. M Wold for the RPA construct. This work was supported by NIH grant CA92245 to JG

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.German J, Schonberg S, Caskie S, Warburton D, Falk C, Ray JH. A test for Fanconi's anemia. Blood. 1987;69:1637–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auerbach AD. A test for Fanconi's anemia. Blood. 1988;72:366–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poll EH, Arwert F, Joenje H, Wanamarta AH. Differential sensitivity of Fanconi anaemia lymphocytes to the clastogenic action of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) and trans-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) Hum Genet. 1985;71:206–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00284574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorsman JC, Levitus M, Rockx D, Rooimans MA, Oostra AB, Haitjema A, Bakker ST, Steltenpool J, Schuler D, Mohan S, Schindler D, Arwert F, Pals G, Mathew CG, Waisfisz Q, de Winter JP, Joenje H. Identification of the Fanconi anemia complementation group I gene, FANCI. Cell Oncol. 2007;29:211–218. doi: 10.1155/2007/151968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling C, Ishiai M, Ali AM, Medhurst AL, Neveling K, Kalb R, Yan Z, Xue Y, Oostra AB, Auerbach AD, Hoatlin ME, Schindler D, Joenje H, de Winter JP, Takata M, Meetei AR, Wang W. FAAP100 is essential for activation of the Fanconi anemia-associated DNA damage response pathway. Embo J. 2007;26:2104–2114. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciccia A, Ling C, Coulthard R, Yan Z, Xue Y, Meetei AR, Laghmani el H, Joenje H, McDonald N, de Winter JP, Wang W, West SC. Identification of FAAP24, a Fanconi anemia core complex protein that interacts with FANCM. Mol Cell. 2007;25:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, Meyn MS, Timmers C, Hejna J, Grompe M, D'Andrea AD. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–262. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meetei AR, de Winter JP, Medhurst AL, Wallisch M, Waisfisz Q, van de Vrugt HJ, Oostra AB, Yan Z, Ling C, Bishop CE, Hoatlin ME, Joenje H, Wang W. A novel ubiquitin ligase is deficient in Fanconi anemia. Nat Genet. 2003;35:165–170. doi: 10.1038/ng1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meetei AR, Medhurst AL, Ling C, Xue Y, Singh TR, Bier P, Steltenpool J, Stone S, Dokal I, Mathew CG, Hoatlin M, Joenje H, de Winter JP, Wang W. A human ortholog of archaeal DNA repair protein Hef is defective in Fanconi anemia complementation group M. Nat Genet. 2005;37:958–963. doi: 10.1038/ng1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sims AE, Spiteri E, Sims RJ, 3rd, Arita AG, Lach FP, Landers T, Wurm M, Freund M, Neveling K, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD, Huang TT. FANCI is a second monoubiquitinated member of the Fanconi anemia pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:564–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alpi A, Langevin F, Mosedale G, Machida YJ, Dutta A, Patel KJ. UBE2T, the FA core complex and FANCD2 are recruited independently to chromatin: A basis for the regulation of FANCD2 monoubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00504-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meetei AR, Levitus M, Xue Y, Medhurst AL, Zwaan M, Ling C, Rooimans MA, Bier P, Hoatlin M, Pals G, de Winter JP, Wang W, Joenje H. X-linked inheritance of Fanconi anemia complementation group B. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1219–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smogorzewska A, Matsuoka S, Vinciguerra P, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Hofmann K, D'Andrea AD, Elledge SJ. Identification of the FANCI protein, a monoubiquitinated FANCD2 paralog required for DNA repair. Cell. 2007;129:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Andreassen PR, D'Andrea AD. Functional interaction of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 and BRCA2/FANCD1 in chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5850–5862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5850-5862.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantor SB, Bell DW, Ganesan S, Kass EM, Drapkin R, Grossman S, Wahrer DC, Sgroi DC, Lane WS, Haber DA, Livingston DM. BACH1, a novel helicase-like protein, interacts directly with BRCA1 and contributes to its DNA repair function. Cell. 2001;105:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain S, Wilson JB, Medhurst AL, Hejna J, Witt E, Ananth S, Davies A, Masson JY, Moses R, West SC, de Winter JP, Ashworth A, Jones NJ, Mathew CG. Direct interaction of FANCD2 with BRCA2 in DNA damage response pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1241–1248. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid S, Schindler D, Hanenberg H, Barker K, Hanks S, Kalb R, Neveling K, Kelly P, Seal S, Freund M, Wurm M, Batish SD, Lach FP, Yetgin S, Neitzel H, Ariffin H, Tischkowitz M, Mathew CG, Auerbach AD, Rahman N. Biallelic mutations in PALB2 cause Fanconi anemia subtype FA-N and predispose to childhood cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:162–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia B, Dorsman JC, Ameziane N, de Vries Y, Rooimans MA, Sheng Q, Pals G, Errami A, Gluckman E, Llera J, Wang W, Livingston DM, Joenje H, de Winter JP. Fanconi anemia is associated with a defect in the BRCA2 partner PALB2. Nat Genet. 2007;39:159–161. doi: 10.1038/ng1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folias A, Matkovic M, Bruun D, Reid S, Hejna J, Grompe M, D'Andrea A, Moses R. BRCA1 interacts directly with the Fanconi anemia protein FANCA. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2591–2597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levitus M, Rooimans MA, Steltenpool J, Cool NF, Oostra AB, Mathew CG, Hoatlin ME, Waisfisz Q, Arwert F, de Winter JP, Joenje H. Heterogeneity in Fanconi anemia: evidence for 2 new genetic subtypes. Blood. 2004;103:2498–2503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litman R, Peng M, Jin Z, Zhang F, Zhang J, Powell S, Andreassen PR, Cantor SB. BACH1 is critical for homologous recombination and appears to be the Fanconi anemia gene product FANCJ. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howlett NG, Taniguchi T, Olson S, Cox B, Waisfisz Q, De Die-Smulders C, Persky N, Grompe M, Joenje H, Pals G, Ikeda H, Fox EA, D'Andrea AD. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in Fanconi anemia. Science. 2002;297:606–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1073834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy RD, D'Andrea AD. The Fanconi Anemia/BRCA pathway: new faces in the crowd. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2925–2940. doi: 10.1101/gad.1370505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akkari YM, Bateman RL, Reifsteck CA, D'Andrea AD, Olson SB, Grompe M. The 4N cell cycle delay in Fanconi anemia reflects growth arrest in late S phase. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:403–412. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobeck A, Stone S, Costanzo V, de Graaf B, Reuter T, de Winter J, Wallisch M, Akkari Y, Olson S, Wang W, Joenje H, Christian JL, Lupardus PJ, Cimprich KA, Gautier J, Hoatlin ME. Fanconi anemia proteins are required to prevent accumulation of replication-associated DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:425–437. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.425-437.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mi J, Kupfer GM. The Fanconi anemia core complex associates with chromatin during S phase. Blood. 2005;105:759–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobeck A, Stone S, Hoatlin ME. DNA structure-induced recruitment and activation of the Fanconi anemia pathway protein FANCD2. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4283–4292. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02196-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell SP, Dutta A. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:333–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labib K, Hodgson B. Replication fork barriers: pausing for a break or stalling for time? EMBO Rep. 2007;8:346–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Admire A, Shanks L, Danzl N, Wang M, Weier U, Stevens W, Hunt E, Weinert T. Cycles of chromosome instability are associated with a fragile site and are increased by defects in DNA replication and checkpoint controls in yeast. Genes Dev. 2006;20:159–173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1392506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cha RS, Kleckner N. ATR homolog Mec1 promotes fork progression, thus averting breaks in replication slow zones. Science. 2002;297:602–606. doi: 10.1126/science.1071398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Newlon CS, Foiani M. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tercero JA, Diffley JF. Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature. 2001;412:553–557. doi: 10.1038/35087607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu LF, Desai SD, Li TK, Mao Y, Sun M, Sim SP. Mechanism of action of camptothecin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;922:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb07020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trenz K, Smith E, Smith S, Costanzo V. ATM and ATR promote Mre11 dependent restart of collapsed replication forks and prevent accumulation of DNA breaks. Embo J. 2006;25:1764–1774. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stone S, Sobeck A, van Kogelenberg M, de Graaf B, Joenje H, Christian J, Hoatlin ME. Identification, developmental expression and regulation of the Xenopus ortholog of human FANCG/XRCC9. Genes Cells. 2007;12:841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ying CY, Gautier J. The ATPase activity of MCM2-7 is dispensable for pre-RC assembly but is required for DNA unwinding. Embo J. 2005;24:4334–4344. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montes de Oca R, Andreassen PR, Margossian SP, Gregory RC, Taniguchi T, Wang X, Houghtaling S, Grompe M, D'Andrea AD. Regulated interaction of the Fanconi anemia protein, FANCD2, with chromatin. Blood. 2005;105:1003–1009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stokes MP, Michael WM. DNA damage-induced replication arrest in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:245–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2177–2196. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costanzo V, Robertson K, Bibikova M, Kim E, Grieco D, Gottesman M, Carroll D, Gautier J. Mre11 protein complex prevents double-strand break accumulation during chromosomal DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2001;8:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shechter D, Costanzo V, Gautier J. ATR and ATM regulate the timing of DNA replication origin firing. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:648–655. doi: 10.1038/ncb1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho GP, Margossian S, Taniguchi T, D'Andrea AD. Phosphorylation of FANCD2 on two novel sites is required for mitomycin C resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7005–7015. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02018-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qiao F, Mi J, Wilson JB, Zhi G, Bucheimer NR, Jones NJ, Kupfer GM. Phosphorylation of fanconi anemia (FA) complementation group G protein, FANCG, at serine 7 is important for function of the FA pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46035–46045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Kennedy RD, Ray K, Stuckert P, Ellenberger T, D'Andrea AD. Chk1-mediated phosphorylation of FANCE is required for the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3098–3108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02357-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamashita T, Kupfer GM, Naf D, Suliman A, Joenje H, Asano S, D'Andrea AD. The fanconi anemia pathway requires FAA phosphorylation and FAA/FAC nuclear accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13085–13090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chirnomas D, Taniguchi T, de la Vega M, Vaidya AP, Vasserman M, Hartman AR, Kennedy R, Foster R, Mahoney J, Seiden MV, D'Andrea AD. Chemosensitization to cisplatin by inhibitors of the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:952–961. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nomura Y, Adachi N, Koyama H. Human Mus81 and FANCB independently contribute to repair of DNA damage during replication. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1111–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mace G, Bogliolo M, Guervilly JH, Dugas du Villard JA, Rosselli F. 3R coordination by Fanconi anemia proteins. Biochimie. 2005;87:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pichierri P, Rosselli F. Fanconi anemia proteins and the s phase checkpoint. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:698–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson LH, Hinz JM, Yamada NA, Jones NJ. How Fanconi anemia proteins promote the four Rs: replication, recombination, repair, and recovery. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:128–142. doi: 10.1002/em.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pichierri P, Franchitto A, Rosselli F. BLM and the FANC proteins collaborate in a common pathway in response to stalled replication forks. Embo J. 2004;23:3154–3163. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta R, Sharma S, Sommers JA, Kenny MK, Cantor SB, Brosh RM., Jr FANCJ (BACH1) helicase forms DNA damage inducible foci with replication protein A and interacts physically and functionally with the single-stranded DNA-binding protein. Blood. 2007;110:2390–2398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrg2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.