Abstract

STAT4, a critical regulator of inflammation in vivo, can be expressed as two alternative splice forms, a full-length STAT4α, and a STAT4β isoform lacking a C-terminal transactivation domain. Each isoform is sufficient to program Th1 development through both common and distinct subsets of target genes. However, the ability of these isoforms to mediate inflammation in vivo has not been examined. Using a model of colitis that develops following transfer of CD4+ CD45RBhi T-cells expressing either the STAT4α or STAT4β isoform into SCID mice, we determined that while both isoforms mediate inflammation and weight loss, STAT4β promotes greater colonic inflammation and tissue destruction. This correlates with STAT4 isoform-dependent expression of TNF-α and GM-CSF in vitro and in vivo, but not Th1 expression of IFN-γ or Th17 expression of IL-17, which were similar in STAT4α- and STAT4β-expressing T cells. Thus, higher expression of a subset of inflammatory cytokines from STAT4β-expressing T cells correlates with the ability of STAT4β-expressing T cells to mediate more severe inflammatory disease.

Introduction

STAT4 is an important determinant of effector T cell responses. The activation of STAT4 by IL-12 in naïve CD4+ T-cells is essential for their ability to develop into Th1 cells, characterized by their secretion of IFN-γ but not IL-4 or IL-17 upon TCR stimulation (1, 2). Acute activation of STAT4 by IL-12 and IL-23 leads to the production of IFN-γ and IL-17, respectively (3–5). In addition to IFN-γ, Th1 cells also preferentially secrete other proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, GM-CSF and IL-2 (2). While the STAT4-dependence of IFN-γ gene expression has been well characterized (6–9), STAT4-dependent regulation of other Th1 and Th17 proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and GM-CSF is less well-defined (10-13). The requirement for STAT4-dependent cytokine regulation in the development of inflammatory immune responses including Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis, arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) highlights the critical role STAT4 in autoimmune diseases (14). For example, STAT4-deficient mice developed significantly milder inflammation of the colon compared to wild type mice (13). Furthermore, mice that constitutively express STAT4 developed chronic transmural colitis characterized by massive influxes of CD4+ T-cells of the Th1 phenotype (15). In humans, there is evidence that STAT4 is also a pathogenic factor in IBD since STAT4 is constitutively activated in patients with ulcerative colitis and IL-12Rβ2 is markedly upregulated with increased STAT4 activation in patients with Crohn’s Disease (16, 17). Higher levels of the instructive cytokines IL-12 and IL-23 and the Th1 and Th17 produced cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-21, IL-6, and GM-CSF correlate with more severe pathologies in these diseases both in humans and in mice (16, 18–23). In addition, TNF-α is a pathogenic factor in Crohn’s Disease and anti-TNF-α therapies have shown impressive clinical efficacy in these patients (24, 25).

We recently described alternatively spliced STAT4 transcripts, a full-length STAT4α and a STAT4β that lacks a C-terminal transactivation domain (26). Primary T cells expressing either STAT4α or STAT4β were able to promote Th1 development in vitro. However, there were some differences in isoform function. IL-12 stimulation of STAT4α-expressing Th1 cells induced more IFN-γ production than T-cells expressing STAT4β, while STAT4β expressing T-cells proliferated more vigorously in response to IL-12 stimulation (26). Microarray analysis further demonstrated that the STAT4 isoforms regulated many similar genes but each isoform targeted a unique set of genes. The ability of these isoforms to mediate inflammatory disease in vivo has not been examined.

To test the ability of STAT4 isoforms to mediate inflammatory disease, we used a model wherein CD4+CD45RBhi T cells expressing either STAT4α or STAT4β were transferred into SCID recipients to induce colitis. We observed that STAT4β mediated more severe inflammation and this correlated with the ability of STAT4β-expressing T cells to secrete higher levels of a subset of Th1 inflammatory cytokines in vitro and in vivo. Thus, STAT4β, an isoform that lacks the C-terminal transactivation domain, is more efficient than STAT4α in promoting inflammation in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of B6.129S2-Stat4tm1Gr (Stat4−/−) mice was previously described (27). Stat4−/− mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background and strain matched C57BL/6 wild type (WT) control mice were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ (B6 SCID) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The Stat4α and Stat4β transgenic mice were maintained on a Stat4−/− C57BL/6 background. All experiments were approved by the IACUC. The mice were maintained in an SPF barrier facility. Eight to 14 week old female mice were used in the experiments.

Isolation of CD45RBhi and CD45RBlowCD4+ T-cells and Induction of Colitis by Cell Transfer

Spleen and lymph node cells were used as a source of CD4+ cells for reconstitution of B6 SCID recipient mice. CD4+ T-cells were isolated as previously described (28). The enriched CD4+ T-cells were then labeled for cell sorting with FITC-conjugated CD4 and PE-conjugated CD45RB (BD Pharmingen). Subsequently, cells were sorted under sterile conditions by flow cytometry for CD4+CD45RBhi on a FacsVantage machine (Becton Dickinson). The CD45RBhigh and CD45RBlow populations were defined as the brightest staining 10–15% and the dullest staining 15–20% CD4+ T cells, respectively. Intermediate staining populations were discarded. All populations were >99% pure on re-analysis. The purified CD45RBhiCD4+ (4x105) cells diluted in 200 μL of PBS were injected intraperitoneally into B6 SCID recipient mice. A separate group of B6 SCID mice received CD45RBlowCD4+ (4x105) cells as a negative control. The recipient mice were weighed initially, then weekly thereafter. The animals were sacrificed 14 weeks after transfer.

Macroscopic and microscopic assessment of Colon Appearance

Once the animals were sacrificed, tissue samples were taken from each segment of the colon (cecum, ascending, transverse, and descending colon and rectum) and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The samples were routinely processed, sectioned at 5 μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for light microscopic examination. The slides were evaluated by light microscopy in a blind fashion using a semi-quantitative scoring system (29). In brief, four general criteria were evaluated in all sections: (1) severity, (2) degree of mucosal hyperplasia, (3) degree of ulceration, if present, and (4) percentage of area involved. The score was then determined from each slide by the following mathematical formula: ((inflammation score+ ulceration score+ hyperplasia score)x(Area involved score)) for a score range of 0–27. Scores from each section of the colon were averaged to determine the overall histological score per experimental group. Histological grades were assigned in a blinded fashion. For scoring the lamina propria neutrophils, the following scoring system was used and scores were averaged from 5–10 high-powered fields: 0- 0-5 PMNs, 1- 6-10 PMNs, 2- 11-20 PMNs, 3–21 PMNs and above

Cell Preparations and Cytokine Analysis

Splenocytes and mesenteric lymph node (MLN)3 cells were harvested and single cell suspensions were obtained as described previously (30). Viable cells were counted and determined by trypan blue exclusion. Surface and cytoplasmic staining and FACS analysis were performed as previously described (31). 1x106 cells/mL were plated on anti-CD3 coated plates (2 μg/mL) or stimulated with IL-12+IL-18 (1 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL, respectively), or IL-23+IL-18 (4 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL, respectively) for 72 hours. Supernatants were collected and assessed for cytokine production using ELISA as previously described (31). For in vitro differentiated T cells, cell-free supernatants were collected 24 hours after anti-CD3 or cytokine stimulation and assessed for cytokine production using ELISA as previously described (31). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 or 50 ng/mL PMA and 500 ng/mL ionomycin for four hours in the presence of Golgi-plug. For mRNA analysis, total RNA isolated from cells activated with anti-CD3 for 4 h was reverse transcribed and used for qPCR analysis. RNA levels were normalized to β2m as an endogenous control.

In-vitro T-cell culture

For anti-CD3 differentiation with irradiated APCs, naïve CD4+ T-cells were isolated by negative selection according to manufacturer’s protocol (MACS isolation system, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). In order to obtain APCs, splenocytes were depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ cells by incubating with CD4 and CD8 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech) and the flow through of cells from LS columns was collected. Cells were irradiated (30 Gy) and used as APCs in T-cell cultures. Th1 cells were differentiated with 5 ng/mL IL-12 and α-IL-4 (11B11 10 μg/mL) and Th17 cells were differentiated with 2 ng/mL TGF-β1, 100 ng/mL IL-6, 10 ng/mL IL-23, α-IFN-γ (XMG 10 μg/mL), and α-IL-4 (11B11 10 μg/mL) for five days. Cells were expanded on day 3 with 20 U/mL IL-2 and half the concentration of cytokines and neutralizing antibodies for the final two days of culture. For differentiation of cells with IL-23 only, cells were cultured as described (31).

Western Blot analysis and phospho-Stat analysis

For immunoblot, whole-cell protein lysates (100 μg) from 5-day differentiated Th1 cells were immunoblotted with Stat4-H119 Ab (Santa Cruz) and counterblotted for actin (Calbiochem). Densitometry is presented as arbitrary units normalized to expression of actin. Phospho-Stat4 intracellular staining was performed using 1.5% paraformaldehyde fixing of cells prior to methanol permeabilization for 10 min at 4°. Cells were stained using pStat4 Ab (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min. at room temperature and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Results

Th1 cells expressing STAT4β secrete significantly more TNF-α upon TCR stimulation than STAT4α expressing Th1 cells

While previous studies demonstrated that T cells expressing either STAT4α or STAT4β could differentiate into Th1 cells, STAT4α was more efficient than STAT4β in the induction of IFN-γ following IL-12 stimulation. To extend these findings, we examined supernatants from naïve CD4+ T-cells undergoing Th1 differentiation in the presence of IL-12 for IFN-γ production (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous literature, there was significantly less IFN-γ present in the supernatant throughout the differentiation period in STAT4β-expressing and STAT4-deficient cultures. Despite these differences, upon anti-CD3 stimulation of differentiated Th1 cells, there were no significant differences in IFN-γ production between the isoforms (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that the differences in endogenous IFN-γ production stimulated by the Stat4 isoforms during the differentiation period, did not affect the process of differentiation.

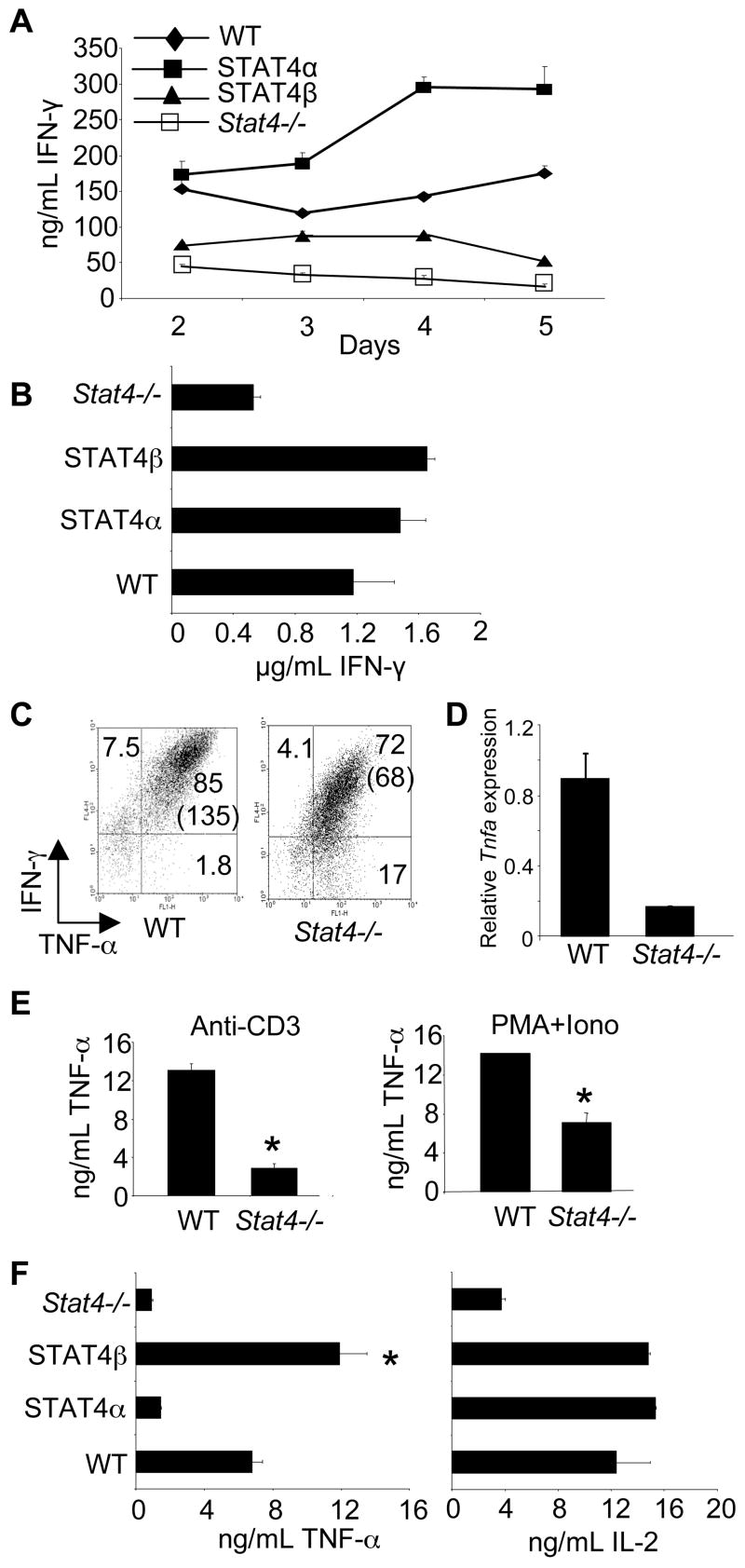

FIGURE 1.

T-cells expressing STAT4 isoforms have differential TNF-α production. A, CD4+CD62L+ T-cells from mice of the indicated genotypes were cultured under Th1 priming conditions (IL-12, anti-IL-4, α-CD3, α-CD28) with irradiated APCs (30 Gy) for five days. Every 24 hours, supernatants of the developing Th1 cells were collected from each genotype. Cell free supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ production using ELISA. Results are represented as mean ± SD. B, Cells cultured as in (A) for five days were stimulated for 24 hours and cell-free supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ using ELISA. Results are represented as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. C, CD4+CD62L+ T-cells were cultured as in (A) for five days. Cells were collected, washed, and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of Golgi-Plug before intracellular staining for the indicated cytokines. Data shown are gated on CD4+ cells. Numbers represent % of cells in the respective quadrant while numbers in parentheses represent the MFI of the x-axis. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. D, RNA was isolated from Th1 cells cultured as in (A) following 4 hours of treatment with anti-CD3. Quantitative PCR was performed for Tnfa mRNA and normalized for β2m expression. Results are relative to WT cells. E, Cells cultured under Th1 priming conditions for five days were stimulated in the indicated condition for 24 hours before cell-free supernatants were collected for analysis of TNF-α. F, Cells cultured as in (A) for five days were stimulated for 24 hours and cell-free supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for TNF-α and IL-2. Results are represented as mean ± SD and are representative of 2–4 independent experiments. *, significantly different (p<0.05) from wild-type, Stat4α, and Stat4−/− Th1 cultured cells using unpaired Student’s T-test.

Although IFN-γ levels were not different between STAT4α- and STAT4β-expressing Th1 cells, we wanted to examine the levels of other cytokines. The dependence of TNF-α production on STAT4 either in vitro or in vivo during the development of disease is not clear (10, 13). To examine STAT4-dependent TNF-α production, wild type and Stat4−/− naïve CD4+ T-cells were cultured in Th1 priming conditions for five days. At the end of the five-day culture, the cells were stimulated with IL-12, IL-12+IL-18, anti-CD3 or PMA+Ionomycin and analyzed for TNF-α and IFN-γ production. Maximal TNF-α production, as assessed by intracellular cytokine staining and mRNA levels, was dependent upon STAT4 (Fig. 1C and D). While the percentage of TNF-α positive CD4+ T-cells did not differ drastically between wild type and Stat4−/− cells, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) at 4 hours and the secretion of TNF-α over a 24-hour time period showed TNF-α production significantly reduced in the absence of Stat4 (Fig. 1C and E). In contrast, TNF-α production was not detected following stimulation with IL-12, in the presence or absence of IL-18 (data not shown).

Having demonstrated the STAT4-dependence in TNF-α production, we wanted to examine the ability of the STAT4 isoforms to prime Th1 cells to secrete TNF-α. Naïve CD4+ T-cells expressing either STAT4α or STAT4β were cultured under Th1 culture conditions for five days and stimulated with anti-CD3 before examining the levels of TNF-α and IL-2 using ELISA. The Th1 cells expressing STAT4β consistently secreted significantly more TNF-α compared to the CD4+ T-cells expressing STAT4α while IL-2 levels between cells expressing the STAT4 isoforms were similar (Fig. 1E). Similar to the data for Stat4−/− cells, decreased TNF-α production from STAT4α-expressing Th1 cells was due to decreased TNF-α per cell compared to STAT4β cultures, with only minor differences in the percentage of TNF-α+ cells, as assessed by intracellular cytokine staining (data not shown). These results suggest that IL-12 stimulation of STAT4β differentially programs the developing Th1 cells to secrete more TNF-α and that this programming is specific and independent of the concentration of IFN-γ throughout the culture period. Thus, these data suggest that STAT4 isoforms can dictate differential cytokine expression in Th1 cells.

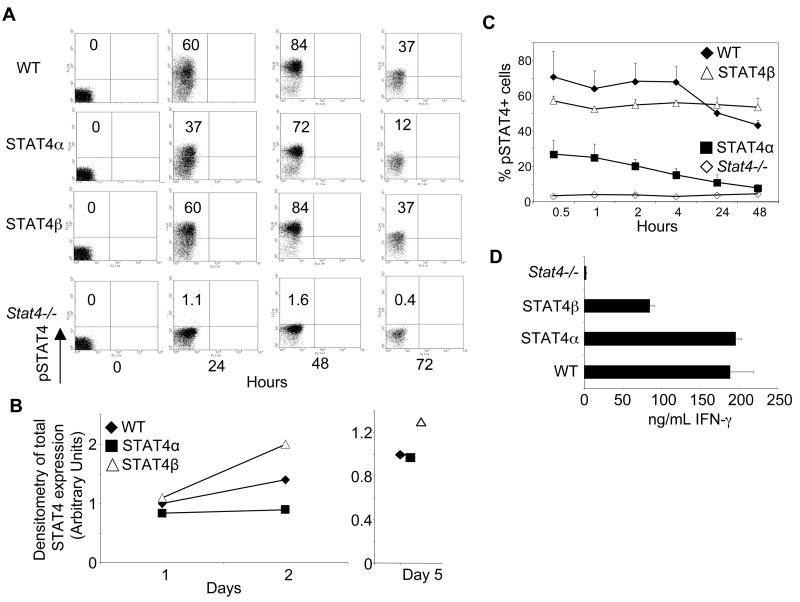

To determine if differential activation of STAT4 contributed to the production of distinct Th cytokines, we stained developing Th1 cultures for phospho-STAT4 (pSTAT4) levels over the first three days of culture. Wild type and STAT4β-expressing cells showed similar percentages of pSTAT4+ cells at all of the time points examined (Fig. 2A). In contrast, there was less pSTAT4 in STAT4α transgenic cells than in wild type cells or STAT4β transgenic cells at all of the time points (Fig. 2A). During this time period there were modest changes in the expression of total STAT4 in each of the cell types (Fig. 2B). After five days of differentiation, IL-12 stimulation resulted in greater induction of pSTAT4 in wild type and STAT4β-expressing cells than in STAT4α-expressing cells, despite similar levels of total STAT4 expression (Fig. 2B and C). Moreover, STAT4 expression did not change over the course of the stimulation (data not shown). Consistent with our previous report (26), STAT4α phosphorylation decreased over time while STAT4β phosphorylation stayed constant over the 48-hour assay period (Fig. 2C). Despite lower levels of pSTAT4α during Th1 differentiation and following IL-12 restimulation, STAT4α was still more potent than STAT4β in the acute production of IFN-γ (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that the differential activation of the isoforms in response to IL-12 can contribute to differential gene expression but that the amount of activated STAT4 does not directly correlate with IFN-γ gene transcription.

FIGURE 2.

Activation kinetics of the STAT4 isoforms during Th1 differentiation. A, Naïve CD4+ T cells freshly isolated (0 time point) or cultured in Th1 conditions for 24, 48, or 72 hours were collected for intracellular staining with anti-pStat4. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. Numbers in quadrants represent % of pSTAT4+ T cells. B, Total cell extracts from WT and STAT4 transgenic T cells were immunoblotted for STAT4 protein levels at day 1, 2 and 5 of Th1 differentiation. Data is presented as arbitrary units of densitometry normalized to actin expression and relative to WT day 1 in the left panel or WT day 5 in the right panel. C, Th1 cells cultured for 5 days were washed and stimulated with IL-12 for the indicated time points before being intracellular stained for pSTAT4. Data are shown for the averages of duplicate samples of representative data. D, Th1 cells were stimulated with IL-12 and IL-18 for 24 hours and cell-free supernatants were analyzed for IFN-γ using ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± SD.

STAT4 isoforms are equally efficient in promoting Th17 differentiation

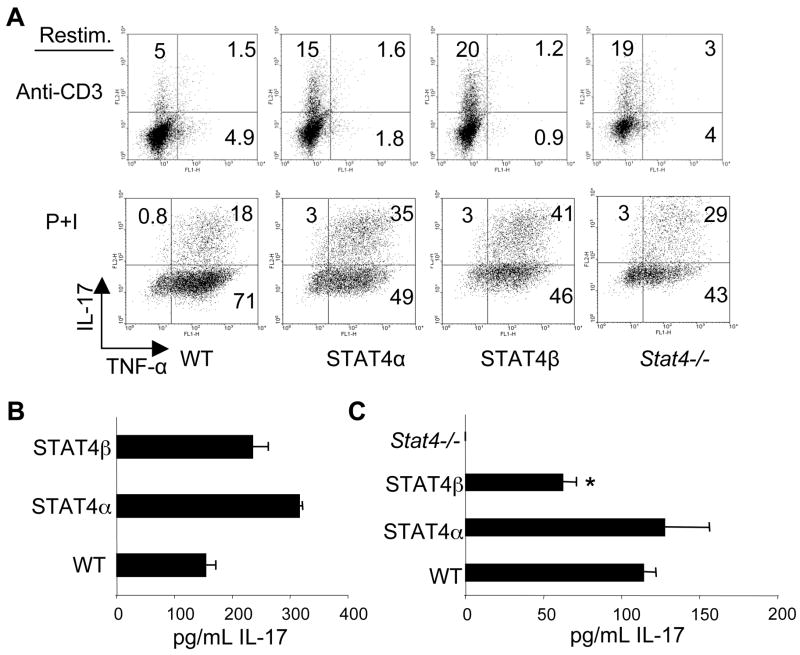

IL-23 also activates STAT4 and induces Th17 cells to secrete IL-17 (4). Since we observed a differential induction of Th1 cells to secrete TNF-α by the STAT4 isoforms, we examined the ability of Th17 cells expressing STAT4 isoforms to secrete IL-17 and TNF-α. We differentiated naïve T-cells with TGF-β1, IL-6, and IL-23 for five days and stimulated cells with anti-CD3 or PMA + Ionomycin (Fig. 3A). There were no significant differences between the percentage of TNF-α positive cells in Th17 cells expressing either isoform although the percentage of TNF-α positive cells was considerably higher following PMA + ionomycin stimulation, compared to anti-CD3 (Fig. 3A). The Th17 cells expressing either isoform had similar capabilities to produce IL-17. As we have previously shown that generation of Th17 cells by TGFβ + IL-6 is independent of STAT4 (31), we also examined the effects of culture with IL-23 on IL-17 production from STAT4 isoform expressing T cells. After a week of culture in IL-23 cells were re-stimulated with anti-CD3 and IL-17 production was analyzed using ELISA. There was also no defect in IL-17 production from T cells expressing either STAT4 isoform, and production was increased compared to wild type cells (Fig. 3B). To assess the responsiveness of the STAT4 isoforms to IL-23-induced cytokine production, we examined IL-17 levels by ELISA after 24 hours of stimulating the cells with IL-23 and IL-18 (Fig. 3C). T cells expressing the STAT4α isoform secreted similar amounts to wild type cells and significantly more IL-17 than cells expressing the STAT4β isoform. Thus, while either STAT4 isoform is sufficient for the generation of Th17 cells, activation of STAT4α by IL-23 can more efficiently induce IL-17 than the STAT4β isoform.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of STAT4α and STAT4β expression on Th17 differentiation. A, CD4+CD62L+ T-cells were cultured in the presence of TGF-β1, IL-6, IL-23, anti-IL-4, and anti-IFN-γ for 5 days. Cells were collected, washed, and stimulated with plate-bound α-CD3 or PMA and Ionomycin (P+I) in the presence of Golgi-Plug before intracellular staining for the indicated cytokines. CD4+ cells were gated and the results were plotted as indicated. Numbers represent % of cells in the respective quadrant. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. B, Total CD4 T cells were cultured for five days in the presence of IL-23 before restimulation with anti-CD3 and assessing production of IL-17A using ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. C, T cells cultured as in (B) were stimulated with IL-23 and IL-18 for 24 hours and cell-free supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IL-17A. Results are shown as mean ± SD of results from 2–4 independent experiments.

STAT4β promotes more severe colitic inflammation than STAT4α

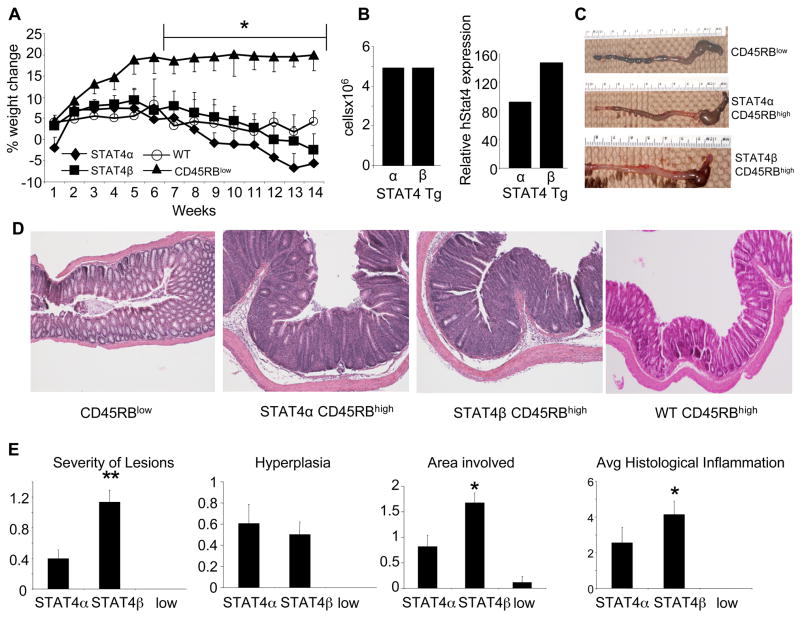

Since we observed some differences in the ability of T cells expressing STAT4α or STAT4β to secrete inflammatory cytokines, we wanted to test the ability of the T-cells expressing each isoform to mediate inflammation. Therefore, we reconstituted SCID mice with CD4+CD45RBhigh or CD4+CD45RBlow T-cells that expressed either STAT4α or STAT4β and examined the weight loss kinetics of the mice. There was no significant difference in the kinetics of weight loss or the end point weight loss between the SCID mice reconstituted with either isoform or wild type mice (Fig. 4A). However, there was a significant difference between the weight loss of mice reconstituted with the CD4+CD45RBhigh cells compared to the mice reconstituted with CD4+CD45RBlow cells, indicating that the CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells expressing either isoform were sufficient to induce colitis (Fig. 4A). As wild type mice had the same overall disease course as STAT4 isoform-expressing cells, we focused further analysis on the comparison between cells expressing the transgenic STAT4 isoforms. To determine if the differences in T cell proliferation between the STAT4 isoforms seen previously in vitro (26) resulted in differences in cell reconstitution in vivo, we determined the absolute CD4+ cell numbers in MLN cells and the percentage of CD4+ T-cells in the splenocytes and observed no significant difference between the repopulation efficiency of the CD4+ T-cells expressing either isoform (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Similar to protein levels seen in Fig. 2B, STAT4 mRNA expression was slightly higher in STAT4β-expressing cells than STAT4α-expressing cells in vivo (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

STAT4α and STAT4β mediate inflammatory bowel disease. A, The change of weight over time is expressed as percent of the original weight. Data represent the mean ± SEM of each group (7–10 mice per group). Mice were sacrificed 14 weeks after T-cell reconstitution. *, CD45RBlow cells are significantly different (p<0.05) from CD45RBhigh WT, STAT4α or STAT4β using 2-way ANOVA and unpaired Student’s T-test post-hoc. B, MLN single-cell suspensions were counted and surface stained for CD4 and analyzed by FACS. Absolute cell numbers were calculated from % of CD4+ cells and cell counts (left panel). QPCR was performed for STAT4 using cDNA made from MLN RNA (right panel). C, Gross appearance of representative colon from each group as indicated. D, Representative photomicrographs (100x) of colon from mice of the indicated group were stained with H&E. E, The mean histological scores ± SEM for the SCID mice reconstituted with the CD4+ T-cells as indicated with STAT4α or STAT4β signifying histological scores from the SCID mice reconstituted with the CD45RBhigh subset and the low signifying histological scores from the SCID mice reconstituted with the CD45RBlow subset. *, p<0.05 where STAT4β is significantly different from both STAT4α and the CD45RBlow subset using the Mann-Whitney U-test.

Although weight loss was not significantly different between the SCID mice reconstituted with either STAT4 isoform, gross examination of the colon and scoring of the slides showed that the SCID mice reconstituted with the CD4+CD45RBhigh cells expressing the STAT4β isoform had more significant mucosal inflammation than the SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4α as assessed by area and severity of the lesion (Fig. 4C–E). There was no difference in mucosal hyperplasia between the mice reconstituted with STAT4α or STAT4β expressing T cells. Importantly, SCID mice reconstituted with the CD4+CD45RBlow cells had essentially no inflammatory infiltrates into the tissues (Fig. 4E).

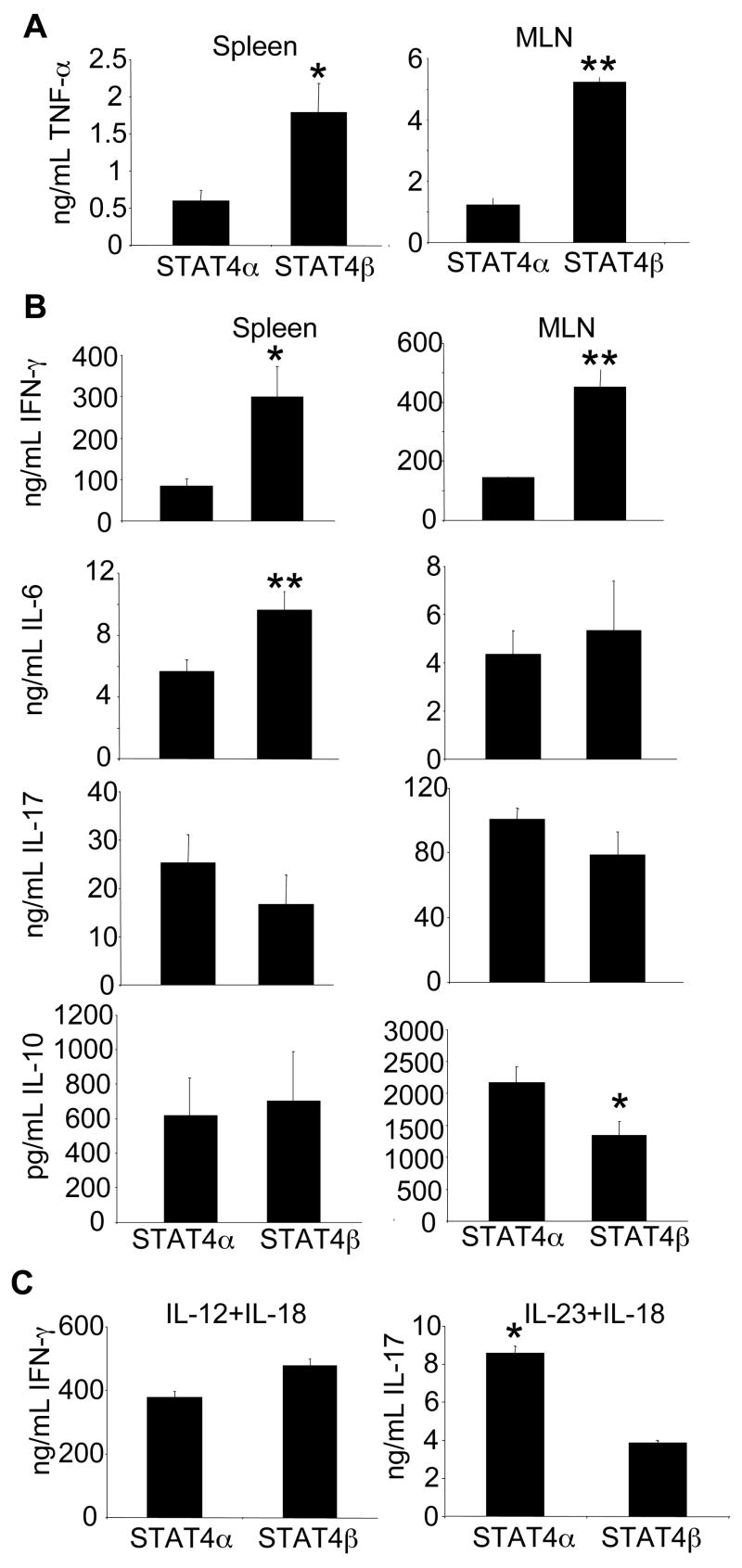

STAT4β expressing T-cells from colitic mice have increased inflammatory cytokine production compared to mice reconstituted with STAT4α T-cells

To examine whether the increased histological inflammation seen in the SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4β expressing T-cells correlated with increased TNF-α production, isolated splenocytes and MLN cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 to assess ex vivo TNF-α production (Fig. 5A). The SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4β expressing T-cells had significantly more TNF-α compared to the mice adoptively transferred with the STAT4α T-cells upon stimulation with anti-CD3. SCID mice reconstituted with CD4+CD45RBlow from either isoform had barely detectable TNF-α that was significantly less than the cells isolated from the SCID mice reconstituted with the CD45RBhigh subset of cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Cytokine production from STAT4α- and STAT4β-expressing T cells ex vivo. (A and B) Cells were isolated and stimulated as described in Materials and Methods and concentration of cytokines were determined by ELISA and are displayed as mean ± SEM (Stat4α n=9; Stat4β n=10). *, p<0.05, ** p<0.02 using Unpaired Student’s T-test. C, Cells were isolated and stimulated as described in Materials and Methods. The concentration of cytokines were determined by ELISA and are displayed as mean ± SD of pooled MLNs from the SCID mice reconstituted with the CD45RBhigh subset of the indicated STAT4 isoform. *, p<0.05 using unpaired Student’s T-test.

To determine if the STAT4 isoforms differentially regulated other cytokines in vivo, we examined T-cell produced cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of colitis, including IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-17 (Fig. 5B). Corresponding to the level of inflammation, SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4β expressing T-cells had more inflammatory cytokine production. IFN-γ production was significantly increased from STAT4β expressing cells compared to STAT4α expressing cells from either spleen or MLNs. IL-6 production in the spleen was also increased but not in the MLNs of mice reconstituted with the STAT4β T-cells. IL-17 did not significantly differ between SCID mice reconstituted with T-cells expressing either isoform, and IL-10 was detected at higher levels from MLNs in mice reconstituted with STAT4α-expressing T cells but there was no significant difference in production detected from spleen cells (Fig. 5B). There was no significant difference in TGFβ1 expression in MLN (data not shown). Since previous data (26) and data in Figures 2 and 3 show that STAT4α is more efficient than STAT4β in cytokine stimulated production of IFN-γ and IL-17, we next examined the MLN cells from colitic mice for their ability to produce these cytokines following treatment with IL-12 and IL-18 or IL-23 and IL-18 for 72 hours. While the IL-23 and IL-18 stimulated cells from the SCID mice reconstituted with STAT4α secreted more IL-17, similar to results from in vitro differentiated cells, there was no significant difference in the amount of IFN-γ secreted from the cells isolated from the SCID mice reconstituted with either isoform (Fig. 5C). Overall, these data indicate that the increased inflammatory disease caused by STAT4β-expressing T cells correlates with increased inflammatory cytokine production.

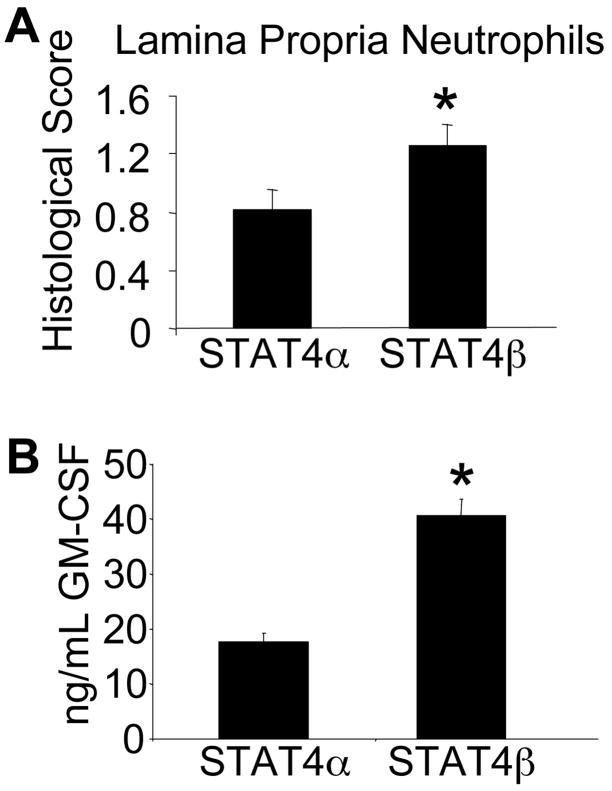

Previous literature suggested that TNF-α and GM-CSF are important in neutrophil chemotaxis to inflamed tissues (19, 32). To examine whether the increased TNF-α secretion from STAT4β expressing T-cells correlated with increased neutrophils in the lamina propria, we analyzed microscopic sections of the colon for PMN infiltration. Consistent with the increased TNF-α seen in the SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4β isoform, there were also increased neutrophils present in the lamina propria compared to the SCID mice reconstituted with STAT4α (Fig. 6A). Since anti-TNF therapies have been shown to inhibit GM-CSF production, we next wanted to look at GM-CSF levels in the mice with colitis (19). We examined supernatants from stimulated MLN cell cultures to assess GM-CSF production (Fig. 6B). Consistent with the increased neutrophil infiltration, GM-CSF was significantly increased from STAT4β-expressing T-cells, further supporting the ability of T-cells expressing the STAT4β isoform to mediate potent inflammatory responses.

FIGURE 6.

Increased lamina propria neutrophil infiltration correlates with increased GM-CSF levels seen in the SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4β isoform. A, PMN scores were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05 using Mann-Whitney U test. B, Single cell suspensions from MLNs were pooled from the indicated mice, stimulated with anti-CD3 for 72 hours and cell-free supernatants were analyzed using ELISA for GM-CSF. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *, p<0.05 using unpaired Student’s T-test.

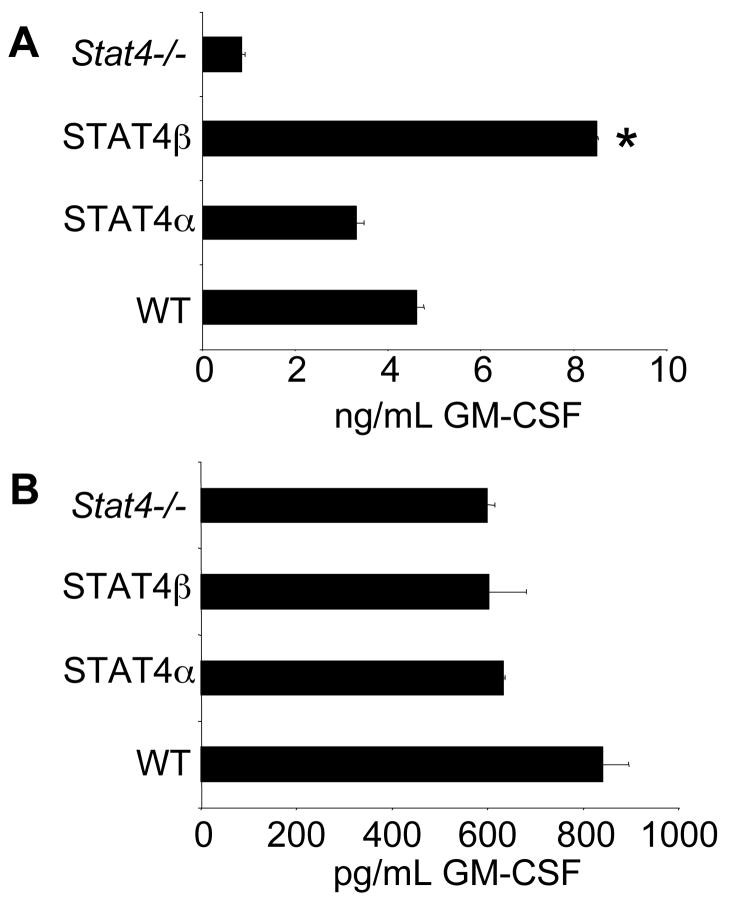

Since there was increased GM-CSF production from STAT4β-expressing cells ex vivo, we wanted to define whether this reflected an increased propensity for STAT4β-expressing T cells to produce GM-CSF or whether it was a result of the in vivo inflammatory environment. To test this, we isolated naïve T-cells expressing either isoform and differentiated them in Th1 or Th17 conditions for five days and stimulated them with anti-CD3 to examine their ability to secrete GM-CSF. Production of GM-CSF in Th1 cultures was dependent upon STAT4 (Fig. 7A). Consistent with what we observed in the ex vivo stimulated cells, the STAT4β expressing Th1 cells secreted significantly more GM-CSF than STAT4α expressing Th1 cells. In contrast, there was no STAT4-dependence for GM-CSF production from Th17 cells and no significant difference in the amount of GM-CSF produced by Th17 cells expressing either Stat4 isoform (Fig. 7B). No detectable GM-CSF was secreted upon acute stimulation with IL-12 or IL-23 with or without IL-18 suggesting that STAT4 does not directly induce transcription of GM-CSF (data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate the increased inflammatory propensity of T cells expressing STAT4β and suggest that the increased inflammatory cytokine production by STAT4β-expressing T cells results in greater inflammatory disease in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

STAT4β Th1 cells are programmed to secrete more GM-CSF than STAT4α Th1 cells. A, CD4+CD62L+ T-cells were primed for Th1 differentiation using the same conditions as in Fig. 1. After five days, cells were stimulated for 24 hours and cell-free supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for GM-CSF. Results are represented as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *, p<0.05 using unpaired Student’s T-test. B, Cells cultured under Th17 conditions as in Fig. 3A for five days were stimulated for 24 hours and analyzed by ELISA for GM-CSF production. Results are presented as mean ± SD and are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

While STAT4 is well known as an important regulator of inflammatory responses, the abilities of the STAT4 isoforms, STAT4α and STAT4β to mediate inflammatory disease has not been well characterized. In this report we use a model of inflammatory bowel disease to demonstrate differing abilities of STAT4 isoforms to promote tissue inflammation. We demonstrate that TNFα and GM-CSF production are STAT4-dependent in Th1 cells and that STAT4β more effectively programs the secretion of these cytokines following subsequent antigen receptor stimulation. Thus, STAT4 isoforms may have differing roles in the development of inflammation.

IBD consists of two chronic, inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis, where CD4+ T-cells play an important role in the dysregulated immune response. Crohn’s Disease is typically associated with a Th1 and Th17 mediated response while Ulcerative Colitis is associated with Th2 response (33). In genetically susceptible individuals, it is thought that CD4+ T-cells activated by environmental antigens and enteric bacteria secrete proinflammatory cytokines and stimulate macrophages within the lamina propria to release a variety of soluble proinflammatory mediators. These mediators recruit leukocytes and stimulate the release of cytokines that damage the epithelial cells and the mucosal tissues creating the ulcerations and edema that characterize these disorders. To date, the most effective therapy has been aminosalicylates, sulfasalazine, corticosteroids and anti-TNF-α therapy, all of which either limit the production or activity of proinflammatory cytokines secreted by the leukocytes (34). As STAT4 has been implicated as a pathogenic factor in Th1 and Th17-mediated autoinflammatory diseases, including IBD (17), we chose an IBD model system where colitis is induced in SCID mice upon reconstitution with CD4+CD45RBhigh T cells to test the roles of STAT4 isoforms in disease. This model system has the advantage of being able to directly test the ability of T-cells expressing the STAT4 isoforms to mediate pathogenesis with minimal manipulation after reconstitution.

Many cytokines seem to play an important role in the development of colitis in this model of IBD. That TNF-α production plays an essential, non-redundant role in the pathogenesis of colitis in this disease model (35) is important as that is one of the cytokines that we observe to be differentially regulated by STAT4 isoforms. IFN-γ was also produced from STAT4β cells at higher levels ex vivo and has a role in disease development. While IL-17 is also critical for disease development, it was produced equally by STAT4α- and STAT4β-expressing T cells suggesting that levels were sufficient for the establishment of disease. Similarly we did not observe any difference in the potential of STAT4α or STAT4β-expressing T cells to differentiate into adaptive T regulatory cells in vitro (data not shown). The differential effect of STAT4 isoforms on TNF-α and GM-CSF is interesting as there are some studies highlighting the cross-regulation of these two cytokines (36, 37). Importantly, infliximab treatment causes a concomitant decrease in both TNF-α and GM-CSF which is thought to contribute to apoptosis of PMNs and lead to decreased inflammation (19). It is possible that the differential expression of the STAT4 isoforms promote Th1 heterogeneity independent of IFN-γ production, due to the ability of STAT4β to enhance the secretion of TNF-α and GM-CSF.

The in vitro and in vivo data were divergent with regard to IFN-γ production upon anti-CD3 stimulation. While the IFN-γ levels were similar in the in vitro differentiated Th1 cells, there was significantly more IFN-γ in the ex vivo stimulated cells of the SCID mice reconstituted with the STAT4β isoform. This was not due to more T-cells being present in the splenocytes or MLNs as the percentage of CD4+ cells in those organs was not significantly different between the SCID mice reconstituted with either isoform (Fig. 3B and data not shown). It is possible that, given the ability of STAT4β to promote IL-12-stimulated proliferation to a greater extent than STAT4α (26) that there might be more differentiated Th1 cells expressing STAT4β in vivo. This would also explain the results with IL-12 and IL-18 stimulation where STAT4β-expressing cells were less responsive following in vitro stimulation, but produced similar levels of IFN-γ to STAT4α-expressing cells when stimulated with cytokine ex vivo. More Th1 cells, even if they produced less cytokine per cell, would generate the result observed. It is also possible that the increased IFN-γ is produced by accessory cells in the ex vivo cultures that might be differentially stimulated by interactions with STAT4α- or STAT4β-expressing cells.

As mentioned above TNF-α may be involved in the regulation of GM-CSF (36, 37). This raised the issue of whether TNF-α might be regulating other aspects of the differentiation of STAT4α or STAT4β-expressing T cells. However, we did not find evidence of significant TNF-α effects on Th1 differentiation. First, expression of Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b was not different among WT, STAT4α-expressing, STAT4β-expressing or STAT4-deficient cells (data not shown). Addition of TNF-α to differentiating cultures of WT, STAT4α- or STAT4β-expressing T cells did not affect growth and led to a modest decrease in IFNγ production from all cultures (data not shown). Expression of Ifngr1 and Ifngr2 was similar in WT, STAT4α-expressing and STAT4β-expressing T cells, although Ifngr2 was increased in Stat4−/− cells, likely due to a lack of ligand-induced downregulation (data not shown)(38). Il12rb2 was similar in WT and STAT4α-expressing cells, though about 50% decreased in STAT4β-expressing cells (data not shown) and also decreased in Stat4−/− cells as previously noted (39). Importantly, the diminished Il12rb2 expression in STAT4β-expressing cells was still sufficient for IL-12-induced STAT4 phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). Culture with TNF-α did not significantly effect expression of Ifngr1, had minor effects on Ifngr2, and only had significant effects on Il12rb2 expression in STAT4β-expressing cells where expression was induced to WT levels (data not shown). Overall, these data suggest that TNF-α does not have a major effect on Th1 development in this culture system.

There is potential clinical relevance to this study. The understanding of STAT4 isoform regulation in vitro or in vivo is unknown. For other human STAT isoforms, including STAT3 and STAT5, differentiation signals like G-CSF can induce the β isoform in myeloid cells (40, 41). In human T cell lines and PBMC, both STAT4α and STAT4β are detectable (26), though it is not known if there are signals that might regulate splicing between the isoforms. It is also unclear whether an individual T-cell expresses both isoforms or whether one isoform is preferentially expressed. It will be important to ascertain the relative amounts of STAT4 isoforms in humans and whether an increase in the STAT4β isoform has any relevance to severity of disease or susceptibility to disease in human patients. It is plausible that there could be an association with an increase in the Stat4β isoform and Th1-mediated autoinflammatory diseases like colitis.

The importance of STAT4 in human disease has been demonstrated both by the requirement for STAT4 in human IL-12 signaling (42) and the association of STAT4 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with autoimmune diseases (43–46). A further understanding of the signals that regulate STAT4 mRNA splicing and the mechanisms through which STAT4 isoforms result in distinct effector phenotypes will be important in characterizing progression in human disease and may provide additional targets for the treatment of disease.

Footnotes

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Award AI45515 and AI57459 (to M.H.K.) from the National Institutes of Health. JTO and GLS were supported by a Training Grant in Immunology and Infectious Disease (T32AI060519).

Abbreviations used in this paper: MLN, mesenteric lymph node, QPCR, quantitative PCR.

References

- 1.Glimcher LH, Murphy KM. Lineage commitment in the immune system: the T helper lymphocyte grows up. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1693–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B, Vega F, Yu N, Wang J, Singh K, Zonin F, Vaisberg E, Churakova T, Liu M, Gorman D, Wagner J, Zurawski S, Liu Y, Abrams JS, Moore KW, Rennick D, de Waal-Malefyt R, Hannum C, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, de Sauvage FJ, Gurney AL. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1910–1914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micallef MJ, Ohtsuki T, Kohno K, Tanabe F, Ushio S, Namba M, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Fujii M, Ikeda M, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M. Interferon-gamma-inducing factor enhances T helper 1 cytokine production by stimulated human T cells: synergism with interleukin-12 for interferon-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1647–1651. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martins GA, Hutchins AS, Reiner SL. Transcriptional activators of helper T cell fate are required for establishment but not maintenance of signature cytokine expression. J Immunol. 2005;175:5981–5985. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishikomori R, Usui T, Wu CY, Morinobu A, O’Shea JJ, Strober W. Activated STAT4 has an essential role in Th1 differentiation and proliferation that is independent of its role in the maintenance of IL-12R beta 2 chain expression and signaling. J Immunol. 2002;169:4388–4398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park WR, Nakahira M, Sugimoto N, Bian Y, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Zhou XY, Yang YF, Hamaoka T, Fujiwara H. A mechanism underlying STAT4-mediated up-regulation of IFN-gamma induction inTCR-triggered T cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:295–302. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grogan JL, Mohrs M, Harmon B, Lacy DA, Sedat JW, Locksley RM. Early transcription and silencing of cytokine genes underlie polarization of T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 2001;14:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claesson MH, Bregenholt S, Bonhagen K, Thoma S, Moller P, Grusby MJ, Leithauser F, Nissen MH, Reimann J. Colitis-inducing potency of CD4+ T cells in immunodeficient, adoptive hosts depends on their state of activation, IL-12 responsiveness, and CD45RB surface phenotype. J Immunol. 1999;162:3702–3710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickensheets HL, Freeman SL, Donnelly RP. Interleukin-12 differentially regulates expression of IFN-gamma and interleukin-2 in human T lymphoblasts. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:897–905. doi: 10.1089/10799900050163271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildner KM, Schirmacher P, Atreya I, Dittmayer M, Bartsch B, Galle PR, Wirtz S, Neurath MF. Targeting of the transcription factor STAT4 by antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides suppresses collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2007;178:3427–3436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson SJ, Shah S, Comiskey M, de Jong YP, Wang B, Mizoguchi E, Bhan AK, Terhorst C. T cell-mediated pathology in two models of experimental colitis depends predominantly on the interleukin 12/Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)-4 pathway, but is not conditional on interferon gamma expression by T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1225–1234. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan MH. STAT4: a critical regulator of inflammation in vivo. Immunol Res. 2005;31:231–242. doi: 10.1385/IR:31:3:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirtz S, Finotto S, Kanzler S, Lohse AW, Blessing M, Lehr HA, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: chronic intestinal inflammation in STAT-4 transgenic mice: characterization of disease and adoptive transfer by TNF- plus IFN-gamma-producing CD4+ T cells that respond to bacterial antigens. J Immunol. 1999;162:1884–1888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parrello T, Monteleone G, Cucchiara S, Monteleone I, Sebkova L, Doldo P, Luzza F, Pallone F. Up-regulation of the IL-12 receptor beta 2 chain in Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 2000;165:7234–7239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pang YH, Zheng CQ, Yang XZ, Zhang WJ. Increased expression and activation of IL-12-induced Stat4 signaling in the mucosa of ulcerative colitis patients. Cell Immunol. 2007;248:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parronchi P, Romagnani P, Annunziato F, Sampognaro S, Becchio A, Giannarini L, Maggi E, Pupilli C, Tonelli F, Romagnani S. Type 1 T-helper cell predominance and interleukin-12 expression in the gut of patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:823–832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agnholt J, Kelsen J, Brandsborg B, Jakobsen NO, Dahlerup JF. Increased production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in Crohn’s disease--a possible target for infliximab treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:649–655. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000108344.41221.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, Mullberg J, Jostock T, Wirtz S, Schutz M, Bartsch B, Holtmann M, Becker C, Strand D, Czaja J, Schlaak JF, Lehr HA, Autschbach F, Schurmann G, Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Ito H, Kishimoto T, Galle PR, Rose-John S, Neurath MF. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:583–588. doi: 10.1038/75068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kullberg MC, Jankovic D, Feng CG, Hue S, Gorelick PL, McKenzie BS, Cua DJ, Powrie F, Cheever AW, Maloy KJ, Sher A. IL-23 plays a key role in Helicobacter hepaticus-induced T cell-dependent colitis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2485–2494. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hue S, Ahern P, Buonocore S, Kullberg MC, Cua DJ, McKenzie BS, Powrie F, Maloy KJ. Interleukin-23 drives innate and T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2473–2483. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteleone G, Monteleone I, Fina D, Vavassori P, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Caruso R, Tersigni R, Alessandroni L, Biancone L, Naccari GC, MacDonald TT, Pallone F. Interleukin-21 enhances T-helper cell type I signaling and interferon-gamma production in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:687–694. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plevy SE, Landers CJ, Prehn J, Carramanzana NM, Deem RL, Shealy D, Targan SR. A role for TNF-alpha and mucosal T helper-1 cytokines in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 1997;159:6276–6282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoey T, Zhang S, Schmidt N, Yu Q, Ramchandani S, Xu X, Naeger LK, Sun YL, Kaplan MH. Distinct requirements for the naturally occurring splice forms Stat4alpha and Stat4beta in IL-12 responses. Embo J. 2003;22:4237–4248. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan MH, Sun YL, Hoey T, Grusby MJ. Impaired IL-12 responses and enhanced development of Th2 cells in Stat4-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;382:174–177. doi: 10.1038/382174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eri R, Kodumudi KN, Summerlin DJ, Srinivasan M. Suppression of colon inflammation by CD80 blockade: Evaluation in two murine models of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:458–470. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bleich A, Mahler M, Most C, Leiter EH, Liebler-Tenorio E, Elson CO, Hedrich HJ, Schlegelberger B, Sundberg JP. Refined histopathologic scoring system improves power to detect colitis QTL in mice. Mamm Genome. 2004;15:865–871. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sehra S, Bruns HA, Ahyi AN, Nguyen ET, Schmidt NW, Michels EG, von Bulow GU, Kaplan MH. IL-4 Is a Critical Determinant in the Generation of Allergic Inflammation Initiated by a Constitutively Active Stat6. J Immunol. 2008;180:3551–3559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathur AN, Chang HC, Zisoulis DG, Stritesky GL, Yu Q, O’Malley JT, Kapur R, Levy DE, Kansas GS, Kaplan MH. Stat3 and Stat4 direct development of IL-17-secreting Th cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4901–4907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souza MH, Melo-Filho AA, Rocha MF, Lyerly DM, Cunha FQ, Lima AA, Ribeiro RA. The involvement of macrophage-derived tumour necrosis factor and lipoxygenase products on the neutrophil recruitment induced by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Immunology. 1997;91:281–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuss IJ, Neurath M, Boirivant M, Klein JS, de la Motte C, Strong SA, Fiocchi C, Strober W. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn’s disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merchant A. Inflammatory bowel disease in children: an overview for pediatric healthcare providers. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2007;30:278–282. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000287199.90860.a9. quiz 283–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corazza N, Eichenberger S, Eugster HP, Mueller C. Nonlymphocyte-derived tumor necrosis factor is required for induction of colitis in recombination activating gene (RAG)2(−/−) mice upon transfer of CD4(+)CD45RB(hi) T cells. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1479–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhoades KL, Cai S, Golub SH, Economou JS. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-4 differentially regulate the human tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter region. Cell Immunol. 1995;161:125–131. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shannon MF, Coles LS, Vadas MA, Cockerill PN. Signals for activation of the GM-CSF promoter and enhancer in T cells. Crit Rev Immunol. 1997;17:301–323. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v17.i3-4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bach EA, Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Ashkenazi A, Aguet M, Murphy KM, Schreiber RD. Ligand-induced autoregulation of IFN-gamma receptor beta chain expression in T helper cell subsets. Science. 1995;270:1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawless VA, Zhang S, Ozes ON, Bruns HA, Oldham I, Hoey T, Grusby MJ, Kaplan MH. Stat4 regulates multiple components of IFN-gamma-inducing signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2000;165:6803–6808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chakraborty A, White SM, Schaefer TS, Ball ED, Dyer KF, Tweardy DJ. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor activation of Stat3 alpha and Stat3 beta in immature normal and leukemic human myeloid cells. Blood. 1996;88:2442–2449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakraborty A, Tweardy DJ. Stat3 and G-CSF-induced myeloid differentiation. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;30:433–442. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson MJ, Chang HC, Pelloso D, Kaplan MH. Impaired interferon-gamma production as a consequence of STAT4 deficiency after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for lymphoma. Blood. 2005;106:963–970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka G, Matsushita I, Ohashi J, Tsuchiya N, Ikushima S, Oritsu M, Hijikata M, Nagata T, Yamamoto K, Tokunaga K, Keicho N. Evaluation of microsatellite markers in association studies: a search for an immune-related susceptibility gene in sarcoidosis. Immunogenetics. 2005;56:861–870. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y, Wu B, Xiong H, Zhu C, Zhang L. Polymorphisms of STAT-6, STAT-4 and IFN-gamma genes and the risk of asthma in Chinese population. Respir Med. 2007;101:1977–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW, de Bakker PI, Le JM, Lee HS, Batliwalla F, Li W, Masters SL, Booty MG, Carulli JP, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L, Chen WV, Amos CI, Criswell LA, Seldin MF, Kastner DL, Gregersen PK. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee HS, Remmers EF, Le JM, Kastner DL, Bae SC, Gregersen PK. Association of STAT4 with rheumatoid arthritis in the Korean population. Mol Med. 2007;13:455–460. doi: 10.2119/2007-00072.Lee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]