Abstract

Hemophilia A is caused by a deficiency in the factor VIII (FVIII) gene. Constrained by limited packaging capacity, even the 4.3-kb B domain-deleted FVIII remained a challenge for delivery by a single adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector. Studies have shown that up to a 6.6-kb vector sequence may be packaged into AAV virions, which suggested an alternative strategy for hemophilia A gene therapy. To explore the usefulness of AAV vectors carrying an oversized FVIII gene, we constructed the AAV-FVIII vector under the control of a β-actin promoter with a cytomegalovirus enhancer (CB) and a bovine growth hormone (bGH) poly(A) sequence. The CB promoter plus bGH signal was shown to be 3- to 5-fold more potent than the mini-transthyretin (TTR) promoter with a synthetic poly(A) sequence for directing FVIII expression in the liver. Despite the 5.75-kb genome size of pAAV-CB-FVIII, sufficient AAV vectors were produced for in vivo testing. Approximately 3- to 5-fold more FVIII secretion was observed in animals receiving AAV-CB-FVIII vectors than in those receiving standard-sized AAV-TTR-FVIII vectors. Both the activated partial thromboplastin time assay and the whole blood thromboelastographic analysis confirmed that AAV-FVIII vectors fully corrected the bleeding phenotype of hemophilia mice. These results suggest that AAV vectors with an oversized genome should be useful for not only hemophilia A gene therapy but also other diseases with large cDNA such as muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis.

Introduction

Hemophilia A is the most common form of hemophilia, comprising more than 80% of all hemophilia cases. This hereditary coagulation disorder is caused by a deficiency in the factor VIII (FVIII) gene (Kaufman et al., 1997; Kaufman, 1999). FVIII plays a critical role in the coagulation cascade by accelerating the conversion of factor X to factor Xa. Although intravenous infusion of plasma-derived or recombinant FVIII protein is an effective treatment in controlling a bleeding episode, the requirement for frequent infusions, because of the short half-life for FVIII (8–18 hr), makes the treatment inherently costly. The most promising cure for this disease appears to be gene therapy, which delivers the functional factor VIII expression cassette directly to the patient (Kay and High, 1999).

Adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors have emerged as one of the most promising vectors for correction of genetic disorders (Muzyczka and Berns, 2002; Flotte and Berns, 2005). It has been adopted in several ongoing human clinical trials for a variety of genetic disorders, including hemophilia B (Flotte and Berns, 2005; Manno et al., 2006). However, the research on using AAV vectors for factor VIII delivery has been lagging because of large size of the factor VIII cDNA, which exceeds the conventional 4.7- to 5.0-kb packaging limit of AAV vectors. At present, development of AAV vectors for FVIII gene delivery has concentrated on two different strategies. One strategy is focusing on innovative approaches to split factor VIII into different vectors (Nakai et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2000; Duan et al., 2001). Although the necessity of using two AAV vectors creates an apparent disadvantage, this concept has been demonstrated to be feasible in animal studies (Nakai et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2000; Duan et al., 2001). In addition, splitting factor VIII into heavy chain and light chain and packaging them into separate AAV vectors was able to overcome the hemophilia A phenotype. Despite the enhancing effects of the light chain on heavy chain secretion (Chen et al., 2007), significantly excessive light chain expression created a “chain imbalance” issue (Scallan et al., 2003). An alternative strategy requires concatemerization of AAV genomes in the correct order to restore functional factor VIII-expressing cassette and only a fraction of AAV genomes can be used for factor VIII gene expression (Nakai et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2000; Duan et al., 2001). The other strategy is to use minipromoter and B domain-deleted factor VIII (BDDFVIII). Using AAV serotype 2, correction of the hemophilia phenotype was observed but the FVIII expression level was low (Sarkar et al., 2003). However, more promising results were observed in mice and hemophilia A dogs with an alternative AAV serotype such as AAV8 (Sarkar et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2006).

AAV is a small DNA virus (virion diameter, 20–25 nm). Many AAV isolates have a genome in the range of 4700 nucleotides (Srivastava et al., 1983; Xiao et al., 1999; Gao et al., 2004). Studies showed that increasing the size of AAV genomes significantly reduces AAV infectivity, which is likely caused by the formation of defective AAV particles with incomplete genomes (Dong et al., 1996; Cao et al., 2000). For recombinant AAV, increasing the size of the vector genome often leads to a decrease in vector packaging efficiency. Despite these potential issues, it has also been reported that AAV vectors could package oversized genomes as large as 5.3–6.0 kb (Grieger and Samulski, 2005). Srivastava's group suggested that up to 3.3-kb vector genomes could be packaged into self-complementary AAV vectors (Wu et al., 2007), which would be equivalent to 6.6 kb in standard AAV vectors. Encouraged by these pioneering studies, we designed an AAV factor VIII vector with a full-size promoter and explored its effectiveness in a hemophilia A model. Our results suggested that large-size AAV vectors could be an alternative strategy for gene therapy of hemophilia A and other genetic diseases with cDNAs exceeding the conventional AAV packaging limits.

Materials and Methods

Tissue culture and transfection

The HEK 293 cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in a moisturized environment supplied with 5% CO2.

AAV vector plasmid construction

The vector plasmid pAAV-TTR-FVIII was kindly provided by Avigen (Alameda, CA) (Jiang et al., 2006), in which B domain-deleted factor VIII cDNA was under the control of a 234-bp transthyretin (TTR) liver-specific promoter along with a 60-bp synthetic poly(A) sequence. To construct pAAV-CB-FVIII, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) region in pAAV-CB-EGFP was replaced with the ClaI- and XhoI-excised fragment from pAAV-TTR-FVIII, which contains the B domain-deleted factor VIII gene. This vector includes a bovine growth hormone (bGH) poly(A) sequence.

AAV vector preparation

Recombinant AAV vector with the factor VIII gene was produced by the triple plasmid cotransfection method as described previously (Hauck et al., 2003). Pseudotype AAV8 vector was packaged by using AAV helper plasmid containing AAV2 rep and AAV8 cap genes. Briefly, AAV helper plasmid, adenovirus function helper plasmid, and AAV-FVIII vector plasmid were cotransfected at a ratio of 1:2:1 into 293 cells cultured in roller bottles. Transfected cells were harvested 3 days later. AAV vectors were purified by two rounds of cesium chloride ultracentrifugation. The collected AAV vectors were then buffer exchanged extensively against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 5% d-sorbitol. The purity and genome titer of the final vectors were evaluated by silver staining and dot blotting, respectively. The obtained vectors were then stored at –80°C.

AAV vector DNA analysis

The size of the single-stranded DNA packaged in AAV capsids was analyzed by alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis. In detail, 40 μl of AAV8-TTR-FVIII or AAV8-CB-FVIII was boiled for 10 min to denature the capsid proteins and release AAV genomes. The obtained DNA was then mixed with 4 μl of loading buffer (300 mM NaOH, 6 mM EDTA, 18% Ficoll type 400, 0.15% bromocresol green) and subjected to alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis. The vector DNA was probed with 32P-labeled factor VIII fragments (1.2 kb, SpeI and KpnI).

Animal procedures

Hemophilia A mice knocked out for FVIII gene exon 16 were obtained from H. Kazazian (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment and supplied with a normal diet. All surgical procedures on mice were done in accordance with institutional guidelines under approved protocols at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

For hydrodynamic injection, 2.0 ml of saline containing 200 μg of column-purified plasmids was injected into the mice, via the tail vein, over 5–10 sec (Al-Dosari et al., 2005). The mice were then allowed to recover before being returned to their cages. Blood was collected 24–48 hr after hydrodynamic injection by tail clipping, using sodium citrate as an anticoagulant at a final concentration of 0.38% (w/v). The resulting blood samples were then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 9000 rpm in a microcentrifuge and the plasma samples were then collected and stored in a –80°C freezer before FVIII assays.

For AAV vector administration, cyclophosphamide was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 μg per mouse on days –3, 0, +3, and +7 to prevent potential immune response against factor VIII in animals. All vectors were diluted in 0.9% saline to a final volume of 200 μl for intravenous injection.

Human FVIII expression and activity assays

Human FVIII concentration in medium or mouse plasma was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), using a commercially available kit from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN) in accordance the procedures recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, capture antibody was reconstituted in coating buffer (0.1 M bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6) to 4 μg/ml. Each well of microtiter plates was then coated with 100 μl of capture antibody solution. After removing the coating antibody and washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 three times, the ELISA plates were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 hr at room temperature. The blocking buffer was then removed and samples in 50 μl of medium or mouse serum were loaded into each well and incubated at 22°C for 2 hr. After the washing step, detection antibody was added to each well and incubated at 20°C for 1 hr. After the final washing procedures, freshly prepared 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) was added to each well. Absorbance was measured at 492 nm and the concentration of factor VIII in the samples was calculated by comparing the absorbance results with a standard curve. FVIII clotting activity was determined by one-stage activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) assay as described previously (Chen et al., 2007). All values were compared with serial dilutions of ReFacto (Wyeth, Philadelphia, PA) mixed into Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or pooled FVIII-deficient mouse serum as standard.

Thromboelastographic measurements

Thromboelastographic measurements were performed by rotation thromboelastometry (ROTEM; Pentapharm, Munich, Germany) in citrated whole blood, using the intrinsically activated tests. The parameters of ROTEM analysis include coagulation time (CT), which corresponds to the reaction time in a conventional thromboelastogram, and clot formation time (CFT), which indicates the coagulation time. All reagents were purchased from Pentapharm.

Statistical analyses

Two-tailed Student t tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni multiple comparison post test were used for result analysis. The differences were considered significant when p < 0.05. Analysis was performed with SPSS 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Experiment Results and Discussion

Construction and packaging of AAV-FVIII vector with large-size genome

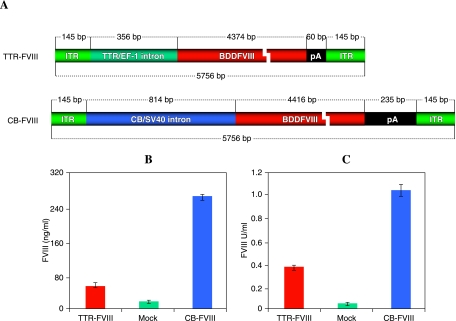

Although it has been documented that viruses usually package no more than 107% of wild-type viral genomes, which translates to approximately 5 kb of DNA for AAV vectors, a number of studies have suggested that up to 140% of wild-type AAV genomes may be accommodated in AAV virions (Grieger and Samulski, 2005; Wu et al., 2007). To explore the maximal capacity of AAV vectors for hemophilia A gene therapy, we constructed an AAV-FVIII vector plasmid with a full-size promoter. As illustrated in Fig. 1A, pAAV-CB-FVIII contains a B domain-deleted human FVIII cDNA driven by a 280-bp chicken β-actin promoter along with a 282-bp cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer. To facilitate transgene expression, a 99-bp simian virus 40 (SV40) intron was also inserted before the factor VIII initial codon. In contrast to a 60-bp synthetic poly(A) sequence in compact pAAV-TTR-FVIII, a full-size bovine growth hormone (bGH) poly(A) sequence was included in pAAV-CB-FVIII.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of key elements of AAV vector carrying the factor VIII gene. In addition to their differences in promoter, the poly(A) sequences for these two vectors are also different. pAAV-CB-FVIII has a bovine growth hormone (bGH) poly(A) signal and pAAV-TTR-FVIII has a synthetic poly(A) signal (60 bp). The size of key elements is indicated. (B and C) Comparison of the strength of the CB promoter and mini-TTR promoter in vivo. Plasmids (pAAV-CB-FVIII or pAAV-TTR-FVIII) were administered to hemophilia A mice (n = 3) by hydrodynamic delivery. Each mouse received 200 μg of DNA diluted in 2 ml of saline. Plasma was collected 24 hr after plasmid administration. The expression of functional FVIII was measured by ELISA (B) and the activity of secreted factor VIII was determined by aPTT assay (C). BDDFVIII, B domain-deleted factor VII; CB/SV40, cytomegalovirus enhancer/simian virus 40; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; pA, poly(A) sequence; TTR/EF-1, minitransthyretin/elongation factor-1 promoter.

To confirm that this new AAV vector with a full-size expression cassette is more potent in directing factor VIII gene expression, we compared the performance of pAAV-CB-FVIII and pAAV-TTR-FVIII in vivo. Unlike the 5.75-kb pAAV-CB-FVIII, pAAV-TTR-FVIII is a traditional factor VIII-expressing vector that is close to 5 kb with a mini-TTR promoter. After hydrodynamic injection of these two plasmids into hemophilia A mice, we analyzed the amount of factor VIII expressed. As shown in Fig. 1B and C, factor VIII expressed from pAAV-CB-FVIII outperformed pAAV-TTR-FVIII by 3- to 5-fold in both the antigen assay and coagulation activity assay. Thus, it is advantageous to use the full-size expression cassette with a CB promoter and a bGH poly(A) sequence for driving factor VIII expression in liver.

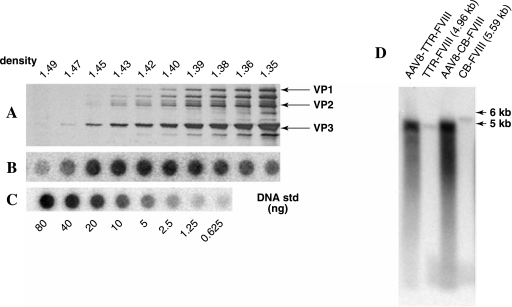

To investigate the performance of pAAV-CB-FVIII in supporting vector packaging, we attempted to produce rAAV-CB-FVIII with AAV8 helper plasmid, miniadenovirus helper plasmid, and pAAV-CB-FVIII. Although the typical yield for pAAV-CB-FVIII was approximately 5- to 10-fold lower than that of our standard recombinant AAV preparations, we were able to generate a sufficient amount of AAV vector with this 5.75-kb vector plasmid. A sample vector preparation using pAAV-CB-FVIII is shown in Fig. 2. The silver staining in Fig. 2A also represents AAV capsid proteins in each gradient fraction. The large amounts of capsid proteins at low densities (less than 1.38 g/ml) suggested empty particles. The slot blot in Fig. 2B shows vector DNA in each gradient fraction. The combined result of silver staining and slot blotting suggested that the majority of AAV vectors containing AAV-CB-FVIII genomes were in the range of 1.30–1.45 g/ml. The wide range of densities of the vectors suggested that the vectors probably encapsidate different lengths of DNA. Compared with the DNA standard, even with 5.75-kb DNA, 5 × 1013 vector genomes of AAV-CB-FVIII were obtained in the 1.40- to 1.45-g/ml fractions in this preparation using 20 roller bottles.

FIG. 2.

Encapsidation of AAV vector with extra large genomes. Vector plasmids AAV-CB-FVIII and AAV-TTR-FVIII were cotransfected into 293 cells along with helper plasmids for AAV production. The transfected cells were then collected 72 hr posttransfection and the vectors were purified by CsCl gradient. At the end of ultracentrifugation, the gradient was collected at 1 ml per fraction. (A) Distribution of AAV-CB-FVIII vectors was determined by silver staining of each fraction. Four microliters of vector in each fraction was used for silver staining. (B) Distribution of AAV-CB-FVIII vectors in each fraction was determined by slot blotting, using a probe specific to factor VIII. One-half microliter of vector in each fraction was used for slot blotting. The standard used to estimate vector yield is included in (C). (D) Alkaline gel analysis of packaged AAV genomes. AAV8-TTR-FVIII and AAV8-CB-FVIII were boiled for 10 min to release single-stranded DNA genomes. The single-stranded DNA genomes were then subjected to alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blotting was then carried out with factor VIII-specific probes. TTR-FVIII and CB-FVIII fragments (4.96 and 5.59 kb, respectively) were included to allow accurate assessment of the size of the packaged AAV genomes.

To demonstrate the size of AAV genomes packaged in the AAV virions, we performed alkaline agarose gel analysis. As shown in Fig. 2D, similar to the standard-sized AAV-TTR-FVIII, the majority of single-stranded DNA packaged from pAAV-CB-FVIII was approximately 5 kb. There were few AAV DNAs detected in the 5.75-kb range. These results suggested that not all the vector sequences were completely packaged into AAV capsids. The wide range of smears for AAV-CB-FVIII also confirmed that a heterogeneous mixture of genomes with different lengths was packaged into AAV capsids.

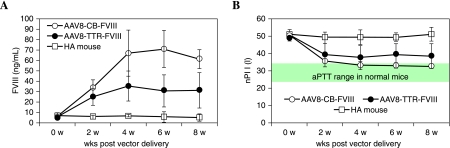

Characterization of the performance of AAV factor VIII vectors with large genomes

To investigate the performance of AAV-CB-FVIII in vivo, we administered AAV-CB-FVIII vectors to a hemophilia A mouse model by intravenous injection. For comparison, we also injected AAV-TTR-FVIII vectors under similar conditions. To avoid the complication of host immune response against factor VIII, we administered four doses of cyclophosphamide to the experimental animals before and after vector administration. As shown in Fig. 3, expression of FVIII was detected 2 weeks after vector delivery and reached its peak at week 6 in both groups. The peak plasma FVIII antigen level at week 6 was approximately 70 ng/ml in mice that received AAV-CB-FVIII, which is in contrast to 30 ng/ml for mice receiving AAV-TTR-FVIII. The coagulation activity of FVIII measured by aPTT assay reached its peak by 4 to 6 weeks after vector delivery (Fig. 3B). The coagulation activity of mice receiving AAV-CB-FVIII vectors was approximately 1 unit/ml, whereas the mice receiving AAV-TTR-FVIII reached only 0.3 unit/ml. The in vivo performance of these vectors was consistent with their performance as hydrodynamically administered plasmids.

FIG. 3.

Expression of factor VIII protein from AAV vectors produced from oversize vector in vivo. The FVIII-deficient mice were under immune suppression with four doses of cyclophosphamide. Each mouse received 2 × 1011 VG of AAV-CB-BDD-FVIII (n = 4, open circles) or AAV-TTR-FVIII (n = 4, solid circles) via intravenous injection. Mouse plasma was collected at the time points specified. (A) Expression of factor VIII was measured by ELISA. (B) Clot formation time was measured by aPTT assay. The control group received mock injections of PBS. The clotting time of normal mice is identified.

To confirm that AAV-mediated gene delivery corrected the hemophilia phenotype, we analyzed the thromboelasto-graphic profile of whole blood collected from mice receiving recombinant AAV factor VIII vectors. These results are summarized in Table 1. The average initiation of coagulation time (CT) in mice receiving AAV-CB-BDD-FVIII or AAV-TTR-FVIII was 120.3 and 141.7 sec, respectively. The CT value for normal mice was 88 sec. The average clot-forming time (CFT) was 29.3 and 30.3 sec for mice receiving AAV-CB-FVIII and AAV-TTR-FVIII, respectively. These results suggested that 5.75-kb AAV-CB-FVIII delivery was able to correct the hemophilia phenotype of factor VIII-deficient animals.

Table 1.

Analysis of Coagulation Profile of Mice Receiving AAV Vectors with Oversized Genomesa

| CT | CFT | |

|---|---|---|

| AAV8-CB-FVIII | 120.3 ± 12.0 | 29.3 ± 0.6 |

| AAV8-TTR-FVIII | 141.7 ± 14.4 | 30.3 ± 3.8 |

| FVIII-deficient mice | 252 ± 8.4 | 48 ± 1.7 |

| Normal mice | 88 ± 10.0 | 28 ± 0.8 |

The blood of mice receiving 2 × 1011 VG/mouse of AAV-CB-BDD-FVIII or AAV-TTR-FVIII via intravenous injection was evaluated for coagulation profile, using ROTEM. Initiation of coagulation was measured as coagulation time (CT). The clot formation time (CFT) was defined as the time needed to achieve a clot firmness of 20 mm. The control group consisted of mice receiving PBS. There was a significant difference between FVIII-deficient mice and mice receiving AAV-CB-BDD-FVIII or AAV-TTR-FVIII (p < 0.05).

In general, AAV vectors carrying more than the wild-type limit of 4.7 kb do not package efficiently. Here we demonstrated that 5.75-kb AAV vectors were able to overcome this hurdle, with enough vectors being produced for in vivo experiments. As shown in Fig. 2, DNA sequence in the virion appeared to be in range of 5 kb, well below the supposed 5.75-kb vector genome. This suggested that there were vector sequence deletions during the encapsidation process. The wide range of densities of vectors also suggested a heterogeneous mixture of genomes of various lengths, which was confirmed by alkaline gel analysis. It is interesting to note that vector DNAs with deletions were able to complement each other and regenerate full-length expression cassettes, which led to a significant level of transgene expression (Fig. 3). Because the content of vector DNA sequence could affect the secondary structure of DNA in the capsids, the packaging of oversized AAV genomes may be sequence dependent. Therefore, not all DNA can be packaged with equal efficiency. Moreover, some capsids, such as AAV8 tested in this study, may be more tolerant of the large DNA content than other AAV serotypes. Future development may be necessary to improve the vector-packaging yield of AAV with large genome-containing virions.

The promoter, a β-actin promoter with a CMV enhancer, is not optimized for expression in the liver. However, with an extra 300-bp capacity as compared with the TTR promoter, there is enough room for future enhancement of the liver-specific promoter. Alternatively, the extra capacity can be used to accommodate an optimized intron or a poly(A) sequence, which have contributed to the improved performance of AAV-CB-FVIII in vivo. It is encouraging that a 5.75-kb AAV FVIII vector could outperform the standard size AAV-TTR-FVIII vector. Similar AAV vectors may be developed for gene therapy of genetic disorders such as cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy, which also have large cDNA sequences exceeding the packaging limit of canonical AAV vectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Katherine High and Valder Arruda for critical reading of the manuscript and comments. The authors also thank Marlene Webber and Junwei Sun for help in manuscript preparation. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL080789, P30-DK047757-14, R01HL084381, and R01HL069051.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for all authors.

References

- Al-Dosari M.S. Knapp J.E. Liu D. Hydrodynamic delivery. Adv. Genet. 2005;54:65–82. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(05)54004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L. Liu Y. During M.J. Xiao W. High-titer, wild-type free recombinant adeno-associated virus vector production using intron-containing helper plasmids. J. Virol. 2000;74:11456–11463. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11456-11463.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Zhu F. Li J. Lu H. Jiang H. Sarkar R. Arruda V.R. Wang J. Zhao J. Pierce G.F. Ding Q. Wang X. Wang H. Pipe S.W. Liu X.Q. Xiao X. Camire R.M. Xiao W. The enhancing effects of the light chain on heavy chain secretion in split delivery of factor VIII gene. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:1856–1862. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J.Y. Fan P.D. Frizzell R.A. Quantitative analysis of the packaging capacity of recombinant adeno- associated virus. Hum. Gene Ther. 1996;7:2101–2112. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.17-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. Yue Y. Engelhardt J.F. Expanding AAV packaging capacity with trans-splicing or overlapping vectors: A quantitative comparison. Mol. Ther. 2001;4:383–391. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte T.R. Berns K.I. Adeno-associated virus: A ubiquitous commensal of mammals. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005;16:401–407. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G. Vandenberghe L.H. Alvira M.R. Lu Y. Calcedo R. Zhou X. Wilson J.M. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J. Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieger J.C. Samulski R.J. Packaging capacity of adeno-associated virus serotypes: Impact of larger genomes on infectivity and postentry steps. J. Virol. 2005;79:9933–9944. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9933-9944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck B. Chen L. Xiao W. Generation and characterization of chimeric recombinant AAV vectors. Mol. Ther. 2003;7:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. Lillicrap D. Patarroyo-White S. Liu T. Qian X. Scallan C.D. Powell S. Keller T. McMurray M. Labelle A. Nagy D. Vargas J.A. Zhou S. Couto L.B. Pierce G.F. Multiyear therapeutic benefit of AAV serotypes 2, 6, and 8 delivering factor VIII to hemophilia A mice and dogs. Blood. 2006;108:107–115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R.J. Advances toward gene therapy for hemophilia at the millennium. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999;10:2091–2107. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R.J. Pipe S.W. Tagliavacca L. Swaroop M. Moussalli M. Biosynthesis, assembly and secretion of coagulation factor VIII. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 1997;8(Suppl. 2):S3–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay M.A. High K. Gene therapy for the hemophilias [comment] Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:9973–9975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno C.S. Pierce G.F. Arruda V.R. Glader B. Ragni M. Rasko J.J. Ozelo M.C. Hoots K. Blatt P. Konkle B. Dake M. Kaye R. Razavi M. Zajko A. Zehnder J. Rustagi P.K. Nakai H. Chew A. Leonard D. Wright J.F. Lessard R.R. Sommer J.M. Tigges M. Sabatino D. Luk A. Jiang H. Mingozzi F. Couto L. Ertl H.C. High K.A. Kay M.A. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat. Med. 2006;12:342–347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyczka N. Berns K.I. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe D.M., editor; Howley P.M., editor; Griffin D.E., editor; Lamb R.A., editor; Martin M.A., editor; Roizman B., editor; Straus S.E., editor. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai H. Storm T.A. Kay M.A. Increasing the size of rAAV-mediated expression cassettes in vivo by intermolecular joining of two complementary vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:527–532. doi: 10.1038/75390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar R. Xiao W. Kazazian H.H., Jr. A single adeno-associated virus (AAV)-murine factor VIII vector partially corrects the hemophilia A phenotype. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:220–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar R. Tetreault R. Gao G. Wang L. Bell P. Chandler R. Wilson J.M. Kazazian H.H., Jr. Total correction of hemophilia A mice with canine FVIII using an AAV 8 serotype. Blood. 2004;103:1253–1260. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan C.D. Liu T. Parker A.E. Patarroyo-White S.L. Chen H. Jiang H. Vargas J. Nagy D. Powell S.K. Wright J.F. Sarkar R. Kazazian H.H. McClelland A. Couto L.B. Phenotypic correction of a mouse model of hemophilia A using AAV2 vectors encoding the heavy and light chains of FVIII. Blood. 2003;102:3919–3926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A. Lusby E.W. Berns K.I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J. Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. Li J. Xiao X. Overcoming adeno-associated virus vector size limitation through viral DNA heterodimerization. Nat. Med. 2000;6:599–602. doi: 10.1038/75087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. Zhao W. Zhong L. Han Z. Li B. Ma W. Weigel-Kelley K.A. Warrington K.H., Jr. Srivastava A. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors: Packaging capacity and the role of Rep proteins in vector purity. Hum. Gene Ther. 2007;18:171–182. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W. Chirmule N. Berta S.C. McCullough B. Gao G. Wilson J.M. Gene therapy vectors based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J. Virol. 1999;73:3994–4003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3994-4003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z. Zhang Y. Duan D. Engelhardt J.F. Trans-splicing vectors expand the utility of adeno-associated virus for gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:6716–6721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]